Abstract

The GABAB receptors GABAB-R1 and GABAB-R2 have been cloned in several mammalian species, and the functional receptor has been shown to exist as a heterodimeric complex. We have cloned guinea pig GABAB-R1 and GABAB-R2 receptor sequences and, using in situ hybridization and immunocytochemistry for vasopressin (AVP), we found that GABAB-R1 and -R2 receptors are expressed in vasopressin neurones of the supraoptic (SON) and paraventricular nuclei (PVN). Therefore, we used both sharp electrode and whole-cell patch recording techniques to examine the effects of the selective GABAB agonist baclofen on SON and PVN magnocellular neurones and to determine the coupling of the GABAB receptor to effector pathways. Recordings were made in coronal hypothalamic slices from both female (ovariectomized) and male guinea pigs. In the presence of tetrodotoxin (TTX), baclofen hyperpolarized (ΔVmax = 5.6 mV, EC50 = 2.3 μM) SON magnocellular neurones (n = 27) under current clamp, or induced an outward current that reversed at EK (ΔImax = 24.2 pA) in PVN magnocellular neurones (n = 33) under voltage clamp. Seventeen of the 24 biocytin-labelled SON magnocellular neurones were identified as AVP neurones, and ten of the 33 biocytin-labelled PVN neurones were identified as AVP or neurophysin-containing neurones, although all of the cells were clustered in the vasopressin-rich core. In the absence of TTX, baclofen activated an outward K+ current that hyperpolarized SON and PVN neurones and significantly reduced their firing rate. The outward current showed inward rectification and was blocked by the K+ channel blocker barium and the GABAB receptor antagonist CGP 35348. Therefore, GABAB receptors are coupled to inwardly rectifying K+ channels in SON and PVN magnocellular neurones and may play a prominent role in modulating phasic bursting activity in guinea pig vasopressin neurones.

The magnocellular neurones of the hypothalamic paraventricular (PVN) and supraoptic nuclei (SON) synthesize and secrete the peptides vasopressin (AVP) and oxytocin (OT) into the systemic circulation from terminals in the neurohypophysis. AVP plays a key role in controlling fluid balance and tissue osmolarity (Poulain & Wakerley, 1982; Renaud, 1987; Bourque & Renaud, 1990), while OT plays a key role in parturition, milk ejection and maternal behaviour (Wakerley & Lincoln, 1973; Poulain & Wakerley, 1982; Bourque & Renaud, 1990; Crowley & Armstrong, 1992; Luckman et al. 1994; Russell et al. 1995).

The relationship between the firing pattern and peptide release has been extensively characterized in rodents (see Bourque & Renaud, 1990). Oxytocin neurones fire in a random, continuous pattern or in a continuous, high-frequency burst during the suckling response (Poulain & Wakerley, 1982). In contrast, AVP neurones fire phasically in response to hyperosmotic or hypovolaemic conditions in the systemic circulation, resulting in enhanced release of vasopressin into the circulation (see Renaud, 1987). Endogenous cellular mechanisms that utilize intrinsic currents have been proposed to explain phasic firing in magnocellular neurones (see Legendre & Poulain, 1992; Bourque, 1998).

The two hypothalamic nuclei which contain the magnocellular neurones receive GABAergic input from several sources. The dorsomedial and the anterior hypothalamic nucleus, the suprachiasmatic nucleus, the organum vasculosum lamina terminalis and the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis send direct GABAergic projections to the PVN (Pumford et al. 1993; Roland & Sawchenko, 1993; Yang et al. 1994; Richard & Bourque, 1995; Boudaba et al. 1996). The suprachiasmatic nucleus also sends direct projections to the SON (Cui et al. 2000). The GABAergic cells control the magnocellular neurones directly through a post-synaptic GABAA receptor (Decavel & Van den Pol, 1992; Boudaba et al. 1996; Tasker et al. 1998; Mouginot et al. 1998), resulting in an increase in chloride conductance (Jhamandas & Renaud, 1987; Randle & Renaud, 1987; Gribkoff & Dudek, 1990). In the rat, GABAergic cells also indirectly control magnocellular neurones via GABAB receptors on pre-synaptic glutamatergic terminals in the SON (Kombian et al. 1996; Kabashima et al. 1997; Ibrahim et al. 1998; Tasker et al. 1998; Kolaj et al. 2000). Finally, these GABAergic cells are regulated by AVP through a post-synaptic V1a receptor as part of a negative feedback loop (Hermes et al. 2000).

Since the GABAB receptor is G protein-coupled to an inwardly rectifying K+ channel (IK,ir) in other systems (Christie & North, 1988; Chieng & Christie, 1995; Lagrange et al. 1996; Wagner et al. 1999), we hypothesized that functional GABAB receptors would be present within and coupled to IK,ir in magnocellular neurones, and subsequently identified GABAB receptor transcripts in SON and PVN magnocellular neurones. Therefore, we utilized both sharp and whole-cell recordings from the SON and PVN of female and male guinea pigs to ascertain the effects of the selective GABAB receptor agonist baclofen on magnocellular neurones. Some of the results have been presented in abstract form (Slugg et al. 1999a, 2000).

METHODS

Animals

Female and male Topeka guinea pigs (400-600 g) were obtained from our institutional breeding facility, and maintained under conditions of constant temperature (25 °C) and light (on between 06.30 and 20.30 h). Animals were housed with food and water provided ad libitum. We have previously reported that oestrogen modulates the coupling of the GABAB receptor to inwardly rectifying K+ channels (Loose et al. 1991; Lagrange et al. 1996; Wagner et al. 1999); therefore, females were ovariectomized under ketamine and xylazine anaesthesia (33 mg kg−1 and 6 mg kg−1, respectively; S.C.) 4-8 days prior to experimentation and they were housed individually. Males did not receive any surgical treatment, but were housed individually prior to the experiment. All surgical and experimental procedures described in the present study were performed in accordance with institutional (OHSU) guidelines based on NIH standards.

Hypothalamic slice preparation

On the day of the experiment, the animal was decapitated under non-stressful conditions, its brain was rapidly removed from the skull, and the hypothalamus was immediately dissected and submerged in carboxygenated (95 % O2, 5 % CO2) artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF; see below) at 4 °C. Four coronal slices (450 μm) through the rostrocaudal extent of the SON and PVN were cut with the aid of a vibratome. The slices were then transferred to a multi-well auxiliary chamber containing carboxygenated aCSF at 4 °C, that was gradually equilibrated to room temperature until electrophysiological recording began.

Drugs

TTX (tetrodotoxin; Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA); OFQ/N (Phoenix Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA), CGP 35348 (provided by A. Sedlacek, Ciba-Geigy AG, Basel, Switzerland) and baclofen (4-amino-3-[chlorophenyl]butanoic acid; Sigma) were dissolved in milli-Q ultra-pure water and stored at -80 °C. Bicuculline (bicuculline methiodide; Sigma) and BaCl2 (barium chloride dihydrate; Sigma) were dissolved in milli-Q ultra-pure water and stored at 4 °C. A 1 mM stock solution of TTX was diluted to a 1 μM concentration in the aCSF in all drug-containing syringes. A 40 mM stock solution of baclofen was dissolved in the aCSF at 30 or 100 μM concentrations. A 1 mM stock solution of bicuculline was dissolved in aCSF to a final concentration of 5 or 10 μM. A 10 mM stock solution of CGP 35348 was diluted in aCSF to a final concentration of 30 μM. A 20 mM stock solution of BaCl2 was dissolved in milli-Q H2O to a final concentration of 200 μM.

Electrophysiology

During recording, slices were supported on a mesh grid that was submerged just below the fluid surface in a 1 ml capacity recording chamber that was perfused from the bottom with warmed (35 °C), carboxygenated aCSF (304 mosmol l−1, pH 7.4). The carboxygenated aCSF contained the following constituents (mM): NaCl, 124; KCl, 5; Na2HCO3 26; NaH2PO4, 2.6; dextrose, 10; Hepes, 10; MgSO4, 2; and CaCl2, 2. Both aCSF and all drugs (diluted with aCSF) were perfused via a Gilson Minipuls peristaltic pump at a rate of 1.2-1.5 ml min−1.

Sharp microelectrodes were fabricated from borosilicate glass pipettes (1.2 mm o.d.; Dagan, Minneapolis, MN, USA) pulled on a P-87 Flaming Brown puller (Sutter Instrument Co., Novato, CA, USA), and filled with a 3 % biocytin solution in 1.75 M KCl and 0.025 M Tris (pH 7.4). Electrode resistances varied from 100 to 300 MΩ. The membrane potential (Vm) and intracellular current injection were generated and measured by an Axoclamp 2A preamplifier (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA, USA). Current and voltage traces were stored on a digital oscilloscope (Tektronix 2230, Tektronix, Beaverton, OR, USA), and were recorded on a chart recorder (Gould 2200, Gould Inc., Glen Burnie, MD, USA). The signals were amplified with a CyberAmp 320 signal conditioner, digitized with a DigiData 1200 A/D converter (sampling frequency 125 or 1000 Hz), and stored by AxoScope computer software (Axon Instruments) for subsequent analysis.

Following successful impalement, slices were perfused with 1 μM TTX to block spontaneous firing and bicuculline (5-10 μM) was added to block GABAA post-synaptic potentials. TTX and bicuculline were added to all drug-containing solutions, but were not given in those experiments where spontaneous activity was measured. Before applying the agonists, a pre-drug current-voltage (I-V) relationship was established by giving hyperpolarizing and depolarizing current pulses (0.2 Hz; 1 s duration) of varying magnitudes, and monitoring the resultant voltage deflections. Once the response to the agonist had reached steady state (5-8 min), Vm was returned to its original resting state by injection of positive current, and a second, post-agonist I-V relationship was established. Under current clamp conditions, the maximum outward current (ΔImax) was defined as the current necessary to return Vm to the original resting state. The slope conductance was measured by linear regression as the slope of the I-V plots between -60 and -80 mV, and between -100 and -130 mV. The agonist-induced change in slope conductance was calculated as the difference in the pre- and post-drug I-V slope conductances in the -60 to -80 mV and -100 to -130 mV ranges. The inwardly rectifying K+ conductance exhibits voltage dependence, that is, the slope conductance changes in relation to the K+ equilibrium potential (EK = -85 mV). If the conductance increases at membrane potentials hyperpolarized to EK, then the channel is said to be inwardly rectifying.

Whole-cell microelectrodes were fabricated from borosilicate glass pipettes (WPI, Sarasota, FL, USA; 1.5 mm o.d., Relectrode 5-10 MΩ) pulled on a P-97 Flaming-Brown puller. Immediately before use they were filled with an internal solution (pH 7.35) which contained the following constituents (mM): potassium gluconate, 108; KOH, 35; NaCl, 10; MgCl2, 2; EGTA, 11; Hepes, 10; ATP, 1; GTP, 0.25; and biocytin, 14 (0.25 or 0.5 % by weight). Membrane currents of PVN neurones were measured in voltage clamp using an Axopatch 1D preamplifier and a DigiData 1200 for analog to digital conversion. Voltage and current data were generated and collected with pCLAMP software (Axon Instruments). Current and Vm traces were also recorded on a chart recorder (Gould 2200). The calculated electrode-bath potential difference of -10 mV was added to all voltage clamp data off-line prior to analysis. Averaged data from the steady-state portion of the current trace was used for slope-conductance calculations. The average series resistance was 35 ± 2 MΩ. There was no series resistance compensation, and data from cells whose series resistance changed by more than 10 % were discarded.

The microelectrodes were targeted to the dorsolateral magnocellular rich region of the PVN under a low-power dissection microscope (see Fig. 1A for location of AVP magnocellular neurones), and then advanced blindly into tissue using positive pressure in the electrode to maintain a clean tip. Following contact with the tissue, the microelectrode was advanced until either the current deflection indicated an increase in tip resistance or neural unit activity was observed. Negative pressure was then applied through the electrode to achieve a gigohm seal. The slice was perfused with 1 μM TTX and 5 μM bicuculline prior to recording to block spontaneous firing and synaptic potentials. Intracellular access was achieved by additional suction. The evoked current data were generated from a series of 0.5-1 s duration, -60 to -130 mV amplitude, voltage steps. In experiments where spontaneous activity was measured, baclofen was administered in the absence of TTX and bicuculline.

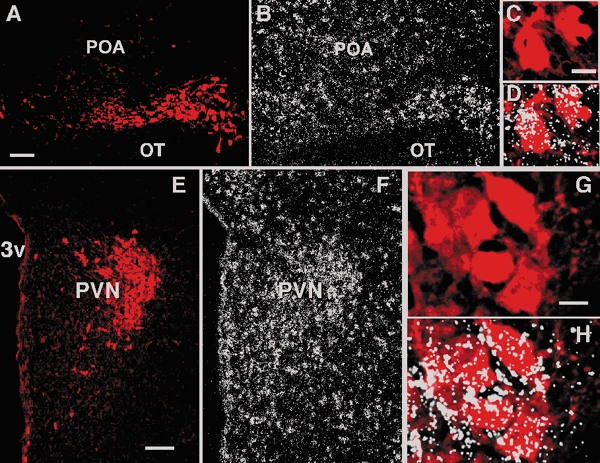

Figure 1. GABAB-R1 mRNA is expressed in vasopressin-containing (AVP) neurones in the guinea pig supraoptic (SON) and paraventricular nuclei (PVN).

Co-localization of AVP fluorescent immunohistochemistry with GABAB-R1 in situ hybidization. A and B, photomicrographs of same section illustrating immunoreactive AVP in the SON (A), and the corresponding autoradiographic grains indicative of GABAB-R1 (B). C, a higher-power image of neurones in A. D, the neurones in C as an overlay with the corresponding autoradiographic grains demonstrating that AVP-containing magnocellular neurones in the SON express GABAB-R1 mRNA. Grains overlay both the AVP cells and some of the spaces between AVP cells. It is likely that these spaces are occupied by oxytocin magnocellular neurones. E and F, photomicrographs of the same section illustrating immunoreactive AVP in the PVN (E), and the corresponding autoradiographic grains indicative of GABAB-R1 (F). G, a higher-power image of the AVP-immunoreactive neurones in the PVN. H, the neurones in G as an overlay with the corresponding hybridization signal (autoradiographic grains) revealed that AVP-containing neurones in the PVN expressed GABAB-R1 mRNA The grains overlay both AVP cells and the spaces in between suggesting that GABAB-R1 mRNA is also expressed in magnocellular oxytocin neurones and parvocellular neurones. POA, preoptic area; OT, optic tract; 3v, third ventricle. Scale bars in A and E represent 100 μm, and in C and G, 10 μm.

Data analyses

In sharp-electrode recordings, a dose-response curve was obtained by sequential application of incrementally increasing single concentrations of baclofen followed by a complete washout until maximum hyperpolarization (ΔVmax) was reached. Individual estimates of the baclofen EC50 were obtained from single neurones via the logistic equation:

fitted by computer (SigmaPlot, Jandel Inc; San Rafael, CA, USA) from the experimental data points. Sharp recordings were also obtained with only a single supramaximal concentration of baclofen (100 μM). The baclofen response was also evaluated a second time after drug washout in the presence of BaCl2 (100-200 μM).

In whole-cell experiments only a single maximum-response concentration (30 or 100 μM) was used. The slope conductance was similarly determined by linear regression of the I-V plots between -60 and -80 mV, and between -100 and -130 mV. The baclofen-induced change in conductance was determined by subtracting the pre- from the post-drug I-V slopes. In some cells baclofen was tested a second time by itself or in the presence of either the GABAB antagonist CGP 35348 or the K+ channel blocker BaCl2 (100-200 μM). A second administration of a maximum concentration of baclofen following a 15 min washout produced a response 80 % or greater than the initial response, indicating that there was a small amount of desensitization in the whole-cell recording. However, there was no desensitization of the baclofen response with an EC50 concentration of baclofen (2 μM) The effects of CGP 35348 alone and in the presence of TTX and bicuculline were also examined.

The statistical comparison of single parameters was made using Student's t test, and between groups and treatments with a two-way analysis of variance using Graphpad Prism software (San Diego, CA, USA). Differences were considered statistically significant if the probability of error was less than 5 % (P < 0.05).

Identification of recorded cells

Following recording, slices were fixed with 4 % paraformaldehyde in Sorensen's phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) for 90-180 min, immersed overnight in 20 % sucrose dissolved in Sorensen's buffer and then frozen in OCT embedding medium (Miles, Inc., Elkhart, IN, USA). Coronal sections (15 μm) were cut on a cryostat and mounted on superfrost slides. These sections were washed with 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), and then processed with streptavidin-Cy2 as described previously (Rønnekleiv et al. 1990). The slides containing either biocytin-labelled cell bodies or proximal dendrites were processed with an AVP antibody (1:2000 dilution, from Dr R. L. Eskay, NIH) as described previously (Erickson et al. 1993a), or a rat neurophysin (RN 4) antibody which labels both AVP and OT neurones (1:2000 dilution; from Dr A. Robinson, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine), and visualized using Cy3 fluorescence immunohistochemistry.

Cloning of guinea pig GABAB-R1 and -R2

cDNAs complementary to the human GABAB-receptor 1 (R1) and GABAB-R2 sequences were cloned using reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). For GABAB-R1, oligonucleotide primers (forward primer, 5′-GGCTTGGCATTTTCTATGGT-3′; and reverse primer 5′-CGTTGTTGTTGGTCGATGAC-3′) were designed from human GABAB-R1 sequences, and targeted sequences that were identical in the alternatively spliced forms, GABAB-R1a and GABAB-R1b (Kaupmann et al. 1998b; Genbank accession numbers, AJ225028 and AJ225029, respectively). For GABAB-R2, the forward primer (5′-GCTCTGGTCATCATCTTCTG-3′) and reverse primer (5′-AGGATCTTTGCATGTTCGAG-3′) were identical to the corresponding human GABAB-R2 cDNA sequence (Genbank accession number AF056085; Clark et al. 2000). Primer synthesis by Life Technologies included, at the 5′-end, a 12 base extension of deoxy-UMP residues used with the PCR cloning kit CloneAmp pAMP10 System (GibcoBRL, Life Technologies). The GABAB-R1 and -R2 fragments were amplified from total RNA extracted from guinea pig cerebral cortex using RT-PCR, and oligo dT16 (GABAB-R1) or random hexamer (GABAB-R2) were used for the cDNA first strand synthesis (GeneAmp kit; Perkin Elmer, Foster City, CA, USA). PCR was conducted for 35 cycles of denaturation (92 °C, 1 min for GABAB-R1 or 45 s for GABAB-R2), annealing (55 °C, 45 s) and extension (72 °C, 45 s), with a 5 min final extension. Each PCR product was subcloned into the pAMP10 vector using the CloneAmp (GibcoBRL Life Technologies) system and sequencing confirmed the products to be GABAB-R1, pan region (345 bp) corresponding to human GABAB-R1a (h2540-2884 bp) and human GABAB-R1b (h2134-2478 bp), and GABAB-R2 (462 bp) corresponding to human GABAB-R2 (h2630-3091 bp) DNAs.

In situ hybridization histochemistry and immunocytochemistry double labelling

For in situ hybridization, the brain was sliced into coronal blocks using a brain slicer (EM Corporation, Chestnut Hill, MA, USA). The preoptic area (POA) and anterior hypothalamic (AH) blocks (2-3 mm) were fixed in 4 % paraformaldehyde in 0.3 M Sorensen's buffer (pH 7.4) for 5-6 h, soaked in 20 % sucrose buffer solution, frozen in OCT embedding medium (Miles, Inc.), sectioned at 15 μm and mounted on superfrost slides.

Sequential in situ hybridization for guinea pig-specific GABAB-R1 or GABAB-R2 mRNA, and immunocytochemistry for vasopressin (VP) were performed on the same hypothalamic tissue sections with minor modifications of previously described methods (Fang & Rønnekleiv, 1999). Briefly, sections were fixed in 4 % paraformaldehyde for 20 min in Sorensen's buffer (pH 7.4), rinsed briefly in Sorensen's buffer, treated with proteinase K (1 μg ml−1) for 8 min at 37 °C, and then treated in 0.1 M triethanolamine (TEA; 1-3 min) followed by 0.25 % acetic anhydride (3-10 min). Sections were prehybridized in hybridization buffer (50 % formamide, 10 % dextran sulfate, 1 × Denhardt's solution, 2 × saline-sodium citrate buffer (SSC), 125 μg ml−1 of yeast transfer RNA and 100 mM dithiothreitol) for 60 min at 58 °C and quickly rinsed in 2 × SSC buffer. Then the sections were hybridized with 35S-labelled antisense riboprobe (2 × 104 d.p.m. μl−1) for at least 18 h at 57 °C. Subsequently, the sections were rinsed in 2 × SSC buffer, reacted with RNase (20 μg ml−1) for 30 min at 37 °C and washed in 2.0 ×, 1.0 ×, 0.5 × SSC at 55-60 °C, to a final stringency of 0.1 × SSC at 60 °C. Thereafter, sections were reacted overnight at 4 °C with a polyclonal VP antibody at a 1:2000 dilution, followed by a sequential 120 min incubation with biotinylated IgG at 1:300 (Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA, USA) and streptavidin-Cy3 (1:500) (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA, USA), respectively. Then sections were washed for 2-3 h in phosphate buffer, briefly rinsed in distilled water, dipped in Kodak NTB-2 nuclear track emulsion and exposed for up to 28 days at 4 °C.

Sections through the SON and PVN were evaluated and photographed under dark-field and/or fluorescent illumination using a Nikon microscope configured with a dark-light attachment (Foster, Inc.), a 100 W Hg lamp and fluorescent red (TRITC HYQ) and green (FITC HYQ) filters. Dark-field and fluorescent views of photomicrographs were illustrated from colour slides using a slide scanner (Polaroid Sprint Scan 35 Plus), Macintosh G4 computer and the Adobe Photoshop software. The approximate location of biocytin-labelled neurones within the magnocellular PVN was measured using the microscope.

RESULTS

GABAB receptor mRNA is expressed in PVN and SON neurones

To study the distribution of GABAB receptor subunits in the hypothalamus and to determine whether these subunits are expressed in magnocellular AVP neurones, we prepared guinea pig-specific PCR clones for GABAB-R1 and -R2. A combination of both subunits is needed for a functional GABAB receptor (Kaupmann et al. 1998a; White et al. 1998). The guinea pig GABAB-R1 cDNA fragment was 92 and 90 % homologous to the corresponding human and rat sequences, respectively. The guinea pig GABAB-R2 cDNA fragment was 90 and 87 % homologous to the corresponding human and rat sequences, respectively.

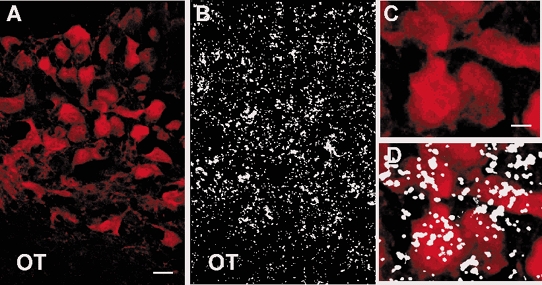

We used in situ hybridization combined with immunocytochemistry to document the expression of GABAB-R1 and -R2 in AVP neurones. GABAB-R1 mRNA was robustly expressed in the PVN and SON, and was strongly co-localized with immunoreactive AVP neurones in both nuclei (Fig. 1). Hybridization product was also observed in areas outside the AVP core and also between AVP neurones, and it is likely that a post-synaptic GABAB receptor is found in both parvocellular neurones and in oxytocinergic magnocellular neurones. GABAB-R2 mRNA, which forms a functional heterodimer with GABAB-R1, was also expressed in SON and PVN neurones, but at a more moderate level. Co-localization of GABAB-R2 and AVP was documented in SON neurones (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. GABAB-R2 mRNA is expressed in AVP-containing neurones in the guinea pig supraoptic nucleus.

Co-localization of fluorescent immunohistochemistry with in situ hybridization. A and B, photomicrographs of same section illustrating immunoreactive AVP in the SON (A), and the corresponding autoradiographic grains indicative of GABAB-R2 (B). C, higher power photograph of the AVP neurones in A. D, overlay of the neurones in C with the corresponding autoradiographic grains in B. The hybridization product was not confined to the AVP neurones, which suggests that GABAB-R2 mRNA is also expressed in oxytocin neurones. Scale bar in A represents 25 μm and in C, 10 μm.

Morphology and immunocytochemical identification of magnocellular neurones

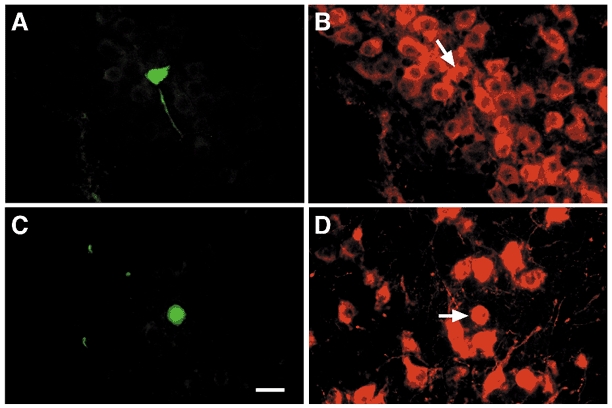

In the SON, a total of 28 cells were recorded with sharp intracellular electrodes under TTX and current clamp conditions from ovariectomized female guinea pigs. The neurones were located either in the rostral SON, dorsolateral to the optic chiasm (n = 4; 14 %), or the retrochiasmatic SON (n = 24; 86 %). The cell bodies of 24 of the 28 SON neurones were identified by streptavidin-Cy2. Consistent with previous publications (Erickson et al. 1993a,b), the labelled cell bodies of the magnocellular neurones ranged in size from 15 μm × 15 μm to 30 μm × 40 μm and were either fusiform or pyramidal in shape, with two to five branching dendrites which exhibited either varicosites and/or spines, (Fig. 3A). The smaller cell bodies were usually cut across the long axis, and the soma was located in two or more 15 μm sections. Seventeen of the 24 cell bodies and major dendritic processes (68 %) identified by biocytin-streptavidin-Cy2 histochemistry also stained positive for arginine vasopressin (AVP+) by immunocytochemistry (Fig. 3B). The AVP+ cells were located in both the caudal retrochiasmatic region (14/21) and in the rostral cap region (3/4) of the SON. Five of the 24 cell bodies (21 %) were dye-coupled to another cell body. An additional eight magnocellular SON neurones were recorded to examine the effects of baclofen on spontaneous firing.

Figure 3. Vasopressin-positive magnocellular neurones respond to baclofen.

A, photomicrograph of the biocytin-streptavidin-Cy2 labelling of a pyramidally shaped (25 μm × 30 μm) magnocellular neurone. The neurone was located 75 μm off the ventral surface just medial to the optic tract in the retrochiasmatic region of the SON. Baclofen (100 μM) hyperpolarized the neurone 11.5 mV (see traces in Fig. 6). B, photomicrograph of the AVP immunoreactivity of the soma of the neurone (arrow) in A as visualized with Cy3. C, photomicrograph of the biocytin-streptavidin-Cy2 labelling of a pyramidally shaped (15 μm × 25 μm) magnocellular neurone. The neurone was located in the dorsal half of the AVP-rich region of the PVN. Baclofen induced a 28 pA outward current (data not shown). D, photomicrograph of the neurophysin immunoreactivity of the soma of the neurone (arrow) in C as visualized with Cy3. An adjacent section contained a fragment of the soma which was immunoreactive for AVP (not shown). Scale bar represents 25 μm for all photomicrographs. Orientation: A and B, medial (right), ventral (bottom); C and D, medial (left), ventral (bottom).

A total of 33 identified magnocellular neurones were recorded with patch electrodes under TTX and whole-cell voltage clamp conditions in the dorsolateral PVN. Twenty-seven of the neurones were from males and six from females. Somas were localized by streptavidin-Cy2 histochemistry. The cell bodies of these magnocellular neurones ranged from 10 μm × 25 μm to 25 μm × 30 μm in size. The morphology of the dendritic and axonal processes was indistinguishable from the SON neurones (e.g. Fig. 3C and Fig. 4). Only two of 16 streptavidin-Cy2-labelled PVN magnocellular somas were positive for AVP, even though all of the somas were within the AVP-rich area of the PVN (Fig. 3D and Fig. 4). Due to the difficulties of staining for AVP in the PVN slice, subsequent cells were immunostained for the carrier protein neurophysin (which labels both AVP and OT neurones) in order to identify PVN magnocells, and 8 of these 17 cells were positive. The distribution of the biocytin-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-identified magnocellular PVN neurones and several morphological examples are shown in Fig. 4.

Figure 4. Location of baclofen-responsive PVN magnocellular neurones.

The locations of 33 recorded magnocellular neurones are shown in relation to a border outlining the heaviest concentration of vasopressin neurones throughout the rostral caudal extent of the PVN. Six representative cells which were positively stained for either vasopressin (marked by asterisk) or neurophysin are shown in the insets.

Resting membrane properties

We utilized both sharp electrode and whole-cell patch protocols to determine the cellular consequences of GABAB receptor activation in SON and PVN magnocellular neurones. There was no difference in the resting membrane potential (RMP) between the PVN neurones from males (-55.1 ± 1.2 mV, n = 27) and PVN neurones from ovariectomized females (-57 ± 2.7 mV, n = 6), but the RMP in the female SON neurones was significantly lower (-50.6 ± 1.3 mV, n = 28; P < 0.02). Since the male and female PVN neurones were similar, the difference between the PVN and SON may be due to the difference in the recording (whole-cell patch versus sharp electrode) technique. However, there was no significant difference in the input resistances between the three groups (male PVN, 526 ± 41 MΩ; female PVN, 633 ± 92 MΩ; and female SON, 621 ± 55 MΩ).

Baclofen hyperpolarizes SON magnocellular neurones under current clamp, and evokes an outward current in PVN cells under voltage clamp

In the SON, baclofen, applied at either a 30 or 100 μM concentration, hyperpolarized 27 of 28 cells recorded under sharp electrode, current clamp conditions and induced a maximum hyperpolarization (ΔVmax) of -5.6 ± 0.6 mV (P < 0.01). The hyperpolarization was accompanied by a decrease in membrane input resistance from 621 ± 55 to 547 ± 50 MΩ. In PVN whole-cell voltage clamp recordings, baclofen induced an outward current (ΔImax = 25.0 ± 2.3 pA, n = 27, in male guinea pigs; ΔImax = 21.0 ± 3.8 pA, n = 6, in female guinea pigs, P > 0.05). An example of the baclofen-induced outward current in a PVN magnocellular neurone is shown in Fig. 5A. The maximum effect of baclofen was observed from 1 to 3 min from the beginning of drug application, and differences in latency are likely due to the depth of the soma and dendrites within the slice. The effects of baclofen dissipated with drug washout and returned to baseline within 10-15 min.

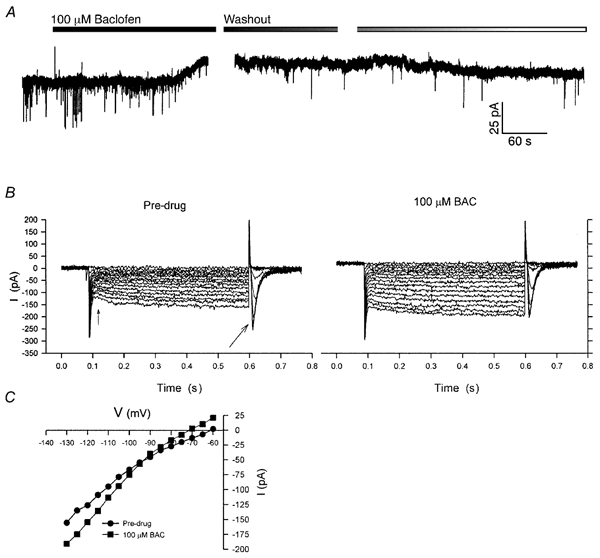

Figure 5. Baclofen activates an inwardly rectifying K+ channel in magnocellular neurones.

Whole-cell patch recording from a PVN magnocellular neurone in the presence of TTX. A, under voltage clamp, administration of 100 μM baclofen induced a 17 pA outward current, which decreased over the course of 10 min following drug washout. The break indicates where the post-drug I-V was determined. Baclofen also acted to reduce the frequency and amplitude of inward PSPs, which showed recovery following drug washout. B, the I-V relationship was determined from a series of 500 ms duration voltage steps, from -60 to -130 mV by 5 mV increments (not shown). The data represent the current deflections resulting from the voltage steps. In the pre-drug period, the cell expressed a baseline inward rectification (i.e. the current response increases at voltage steps greater than -90 mV), an Ih (time-delayed rectification, small arrow), and a T-type Ca2+ current (large arrow). Following administration of 100 μM baclofen, the baseline current shifted positively by 17 pA, and the magnitude of the evoked currents increased, especially for those voltage steps greater than -90 mV. C, plot of I-V relationships for pre-drug vs. 100 μM baclofen (BAC). The I-V curves for baclofen show a reversal at -93 mV and an increase in slope conductance at potentials hyperpolarized to EK, which is characteristic of the inwardly rectifying K+ channel. Resting membrane potential (RMP) = -61 mV; holding potential (Vhold) = -60 mV.

Baclofen effects are dose dependent

A concentration-response curve was determined from four SON magnocellular neurones recorded by sharp electrode that each received sequential baclofen administrations of 1, 3, 10 and 30 or 100 μM (Fig. 6A). A logistic fit of the data revealed an EC50 of 2.3 ± 0.4 μM and a ΔVmax of -7.8 ± 1.5 mV (Fig. 6B). The EC50 value is in close agreement with other studies that examined both pre-synaptic (Kombian et al. 1996; Ibrahim et al. 1998) and post-synaptic effects of baclofen (Christie & North, 1988; Chieng & Christie, 1995; Beck et al. 1995; Lagrange et al. 1996; Shen & Johnson, 1997; Wagner et al. 1999).

Figure 6. Baclofen hyperpolarizes magnocellular neurones in a concentration-dependent manner.

Cells were perfused with successively increasing concentrations of baclofen (BAC, 1-100 μM). A, membrane potential traces from the AVP SON in Fig. 3A and B. Traces represent the 3, 5.5, 9.5 and 11.5 mV hyperpolarizations produced by 1, 3, 10 and 100 μM baclofen, respectively. Drug application is indicated by the horizontal bar. B, composite dose-response relationship for the baclofen-mediated hyperpolarization in four SON magnocellular neurones. Data are expressed as a percentage of the maximum response to 30-100 μM. Symbols (•) represent means, and vertical lines represent S.E.M. of the hyperpolarizations produced by a given concentration. This curve was fit to the data points using a logistic equation (Graphpad Prism). The baclofen EC50 was 2.3 ± 0.4 μM, and the mean ΔVmax was 7.8 ± 1.5 mV.

Baclofen activates a K+ current in magnocellular neurones

Both electrophysiological and pharmacological techniques were used to identify the current underlying the baclofen effect. An example of the evoked current-voltage traces and the calculated I-V is shown in Fig. 5B and C. A population analysis of the pre- and post-baclofen I-V plots showed a reversal potential of -83 ± 2.0 mV for the male PVN cells and -81.7 ± 3.7 mV for the female PVN cells (P > 0.05) which is similar to the calculated Nernst equilibrium potential for K+ (-85 mV) under these conditions. The PVN neurones exhibited a significant baseline voltage-dependent inward rectification (4.71 nS for -100 to -130 mV versus 2.27 nS for -60 to -80 mV; n = 27, P < 0.01). Following application of 30 or 100 μM baclofen, there was a significant increase (25 ± 5 %; P < 0.001) in the -100 to -130 mV slope conductance.

Some magnocellular neurones were also tested with the heavy metal barium, which acts to block the K+ channel pore. Barium attenuated the baclofen-induced changes in the -60 to -80 mV and -100 to -130 mV slope conductances in all the PVN (n = 4, Fig. 7) and SON (n = 4, data not shown) magnocellular neurones that were tested. Collectively, these data strongly suggest that baclofen activates a post-synaptic inwardly rectifying K+ conductance in both the SON and PVN magnocellular neurones.

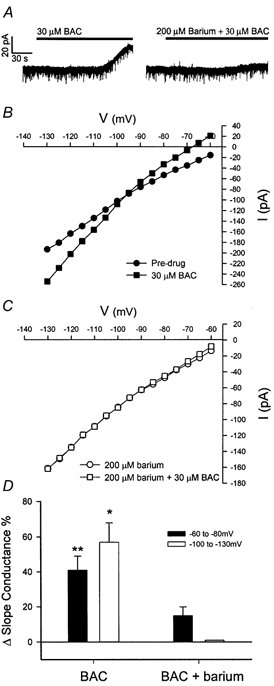

Figure 7. Barium attenuates the outward current mediated by baclofen.

Whole-cell recording from a PVN magnocellular neurone in the presence of TTX and bicuculline. A, baclofen (BAC; 30 μM) evoked a 36 pA outward current. The slice was then treated for 15 min with 200 μM barium, which reduced the response to a subsequent administration of BAC by 86 % to 5 pA. B, I-V plot from the PVN neurone recorded under conditions of pre-drug (•) and 30 μM BAC (▪). The I-V plot shows that the outward current was associated with a significant increase in conductance at membrane potentials negative to EK. C, I-V plot from the same neurone recorded under conditions of pre-drug (○) and 30 μM BAC + 200 μM barium (□). Barium reduced the baclofen effect and completely abolished the increase in slope conductance at membrane potentials negative to EK. D, changes in the mean slope conductance in PVN magnocellular neurones which received BAC alone and BAC in the presence of 200 μM barium. BAC induced a significant increase (41 ± 8 %) in the -60 to -80 mV slope conductance (** P < 0.01) and a significant increase (57 ± 11 %) in the -100 to -130 mV slope conductance (* P < 0.05) in PVN magnocellular neurones (n = 4). Following pre-treatment with 200 μM barium, the increase (15 ± 5 %) in slope conductance in the -60 to -80 mV range was not significantly different, and the increase in the -100 to -130 mV range was completely blocked.

The GABAB receptor antagonist CGP 35348 significantly reduced the baclofen-mediated effects

The selective GABAB receptor antagonist CGP 35348 reduced the baclofen-induced current and slope conductance increase by 50-90 % in PVN (n = 4, Fig. 8). In addition, CGP 35348 alone induced a 7 pA inward current in the PVN (n = 2) when administered with TTX and bicuculline, suggesting that a basal post-synaptic GABAB-ergic tone is present within the slice preparation (data not shown).

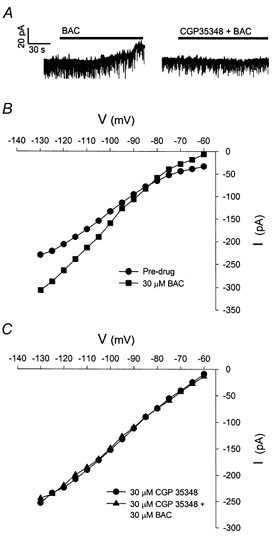

Figure 8. The selective GABAB antagonist CGP 35348 blocks the baclofen response at the GABAB receptor.

Whole-cell recording from a PVN magnocellular neurone in the presence of TTX. A, application of 30 μM baclofen (BAC) evoked a 27 pA outward current. The slice was then treated with 30 μM CGP 35348 for 15 min, and then 30 μM BAC and 30 μM CGP 35348 were co-administered. CGP 35348 treatment reduced the BAC-mediated outward current by 89 %. B, I-V plot from the neurone recorded under conditions of pre-drug (•) and 30 μM BAC (▪). The I-V plot shows that the outward current was associated with a significant increase in conductance at membrane potentials negative to EK. C, I-V plot of the neurone following CGP 35348 treatment. CGP 35348 (•) inhibited the outward current and completely blocked the increase in slope conductance due to BAC (▴). A similar effect was observed in three other PVN neurones.

Baclofen inhibits firing in both SON and PVN neurones

Baclofen was applied to eight SON and one PVN neurone under current clamp conditions. The SON neurones were spontaneously active at their resting membrane potentials, and application of baclofen hyperpolarized the membrane from -5 to -11 mV which significantly inhibited firing (Fig. 9A). All of the neurones returned to the pre-drug firing rate following washout of baclofen from the recording chamber. In five of the eight SON neurones tested, the activity initially returned as bimodal phasic bursts which gradually transitioned to the pre-drug monotonic discharge. Similarly, a spontaneously active PVN neurones was recorded under whole-cell conditions. Switching between current and voltage clamp revealed that the membrane hyperpolarization (-5 mV) was associated with a concurrent outward current (Fig. 9B). As with the SON neurones, the PVN neurone returned to spontaneous activity following baclofen washout.

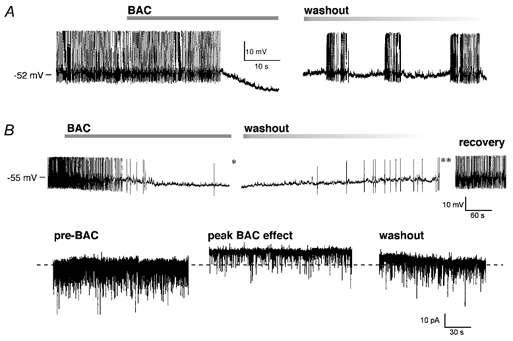

Figure 9. BAC inhibits spontaneous action potential discharge in SON and PVN.

In both examples, baclofen (BAC) only was applied to the neurones, and the action potential amplitude was truncated since the traces were derived from chart recordings. A, in this SON recorded under current clamp BAC hyperpolarized the membrane by 11 mV and caused a complete cessation of firing. After washout of BAC the activity returned as phasic burst firing that gradually shifted to a monotonic discharge after 5 min. RMP -52 mV. B, in this PVN whole-cell recording, both current and voltage clamp data are presented. In current clamp (upper traces), the cell is firing monotonically and application of BAC caused a 5 mV hyperpolarization and an inhibition of the firing (left trace). With the washout of BAC the cell depolarized and resumed firing (middle trace) eventually returning to the initial firing rate (lower traces). In voltage clamp (bottom row), prior to BAC numerous synaptic potentials were present at Vhold (left trace). At the peak of the BAC effect (* in current clamp recording above), there was a 10 pA outward current and a decrease in the synaptic potentials (middle trace). The holding current returned to the baseline as BAC washed out (right trace, at ** in current clamp trace). RMP = -55 mV, Vhold = -60 mV.

DISCUSSION

This study provides for the first time both electrophysiological and morphological evidence for a post-synaptic GABAB-mediated activation of an inwardly rectifying K+ conductance (IK,ir) in guinea pig magnocellular neurones, including vasopressin neurones. While a previous study demonstrated the presence of GABAB receptor transcripts in the SON and PVN (Lu et al. 1999), the in situ hybridization in the present study demonstrates a strong expression of GABAB-R1 mRNA in immunocytochemically identified AVP-positive magnocellular neurones. In addition, we have also measured GABAB-R2 transcripts in AVP-positive magnocellular neurones. Both the R1 and R2 transcripts are required for a functional heterodimer receptor (Kaupmann et al. 1998a; White et al. 1998).

Previously, others have reported either pre-synaptic GABAB-mediated inhibition of both IPSPs and EPSPs or a post-synaptic inhibition of high-threshold Ca2+ currents in rat magnocellular neurones (Kombian et al. 1996; Kabashima et al. 1997; Ibrahim et al. 1998; Harayama et al. 1998; Kolaj et al. 2000). In the present study, we report a post-synaptic response via activation of the GABAB receptor. In 27 of 28 neurones recorded with sharp electrodes in the SON, and in all 33 cells recorded with whole-cell patch electrodes in the PVN, the application of the GABAB agonist baclofen induced a slow outward current that could be blocked by barium, and whose properties were consistent with the activation of IK,ir (Williams et al. 1988a,b; Hille, 2001). The actions of baclofen could also be blocked with the selective GABAB antagonist CGP 35348.

Comparison of GABAB-mediated effects in the SON and PVN in the rat and guinea pig

Interestingly, until recently, previous studies in the rat have demonstrated only a pre-synaptic GABAB-mediated inhibition of transmitter release (Kombian et al. 1996; Kabashima et al. 1997; Ibrahim et al. 1998; Mouginot, 1998; Cui et al. 2000), or a post-synaptic inhibition of high-threshold Ca2+ currents in the male rat (Harayama et al. 1998). Previous studies that used similar methods should have detected a post-synaptic activation of IK,ir in the rat if it were present (Kabashima et al. 1997; Mouginot et al. 1998). Therefore, the post-synaptic coupling of the GABAB receptor to IK,ir in magnocellular neurones in the guinea pig represents a novel finding. Stern et al. (2002) recently reported a membrane hyperpolarization and an inhibition of firing activity following baclofen in rat SON neurones which is similar to the data we are presenting. The post-synaptic mechanism for this phenomenon in the rat is unknown, but it may possibly be an activation of a K+ conductance.

We frequently observed a decrease in the amplitude and frequency of spontaneous IPSPs and EPSPs following administration of baclofen (e.g. Fig. 5A and Fig. 9B), which is consistent with the previous reports of a GABAB-mediated inhibition of EPSPs and IPSPs in the rat. In addition, there was no effect of baclofen or the GABAB antagonist hydroxysaclofen on membrane potential or input resistance in rat oxytocin neurones (Jourdain et al. 1996).

The data in the present study were derived from both SON and PVN magnocellular neurones in the hypothalamus, and it is possible that these two populations receive different types of synaptic input from different regions of the CNS (Tasker et al. 1998). But regardless of the potential differences in synaptic input, the neurosecretory magnocellular neurones serve a similar physiological function, and the guinea pig magnocellular AVP neurones, at least, show a similar robust response to GABAergic activation through the GABAB receptor. Therefore, based on our findings of a consistent response between the SON and PVN magnocellular neurones, it is likely that they receive similar GABAergic innervation.

Oxytocin magnocellular neurones were not immunocytochemically identified in this study. It is possible that some of the unidentified baclofen-responsive recorded neurones were oxytocinergic. Similarly, it is possible that the GABAB-R1 and -R2 mRNA hybridization product located between AVP neurones was expressed by oxytocinergic neurones. Therefore, some of the unidentified neurones were possibly oxytocinergic magnocellular neurones that expressed functional GABAB receptors coupled to IK,ir However, experiments specifically targeting oxytocin neurones need to be carried out to identify a post-synaptic GABAB response.

Potency of the GABAB receptor agonist baclofen in magnocellular neurones

The present pharmacological data are consistent with reports of baclofen actions on GABAB receptors in other systems. The baclofen EC50 for the SON in the present study is similar to the EC50 for GABAB receptor activation in arcuate neurones (Lagrange et al. 1996), hippocampal CA1 and CA3 neurones (Beck et al. 1995), but is somewhat higher than the EC50 found in dissociated rat SON neurones (Harayama et al. 1998), periaqueductal grey neurones (Chieng & Christie, 1995), substantia nigra neurones (Shen & Johnson, 1997) and lateral parabrachial nucleus neurones (Christie & North, 1988). It is therefore likely that the baclofen EC50 for PVN is similar to that for SON.

Previously, we reported that orphanin-FQ/nociceptin (OFQ/N) activates IK,ir in SON magnocellular neurones (Slugg et al. 1999b). This report extends those findings by demonstrating that the GABAB receptor is coupled to IK,ir in SON. In addition, we have evidence to suggest that most SON receive synaptic input from both GABAergic and OFQ/N neurones based on our finding that the majority (12/14, 86 %) showed a response to both baclofen and OFQ/N (R. M. Slugg & M. J. Kelly, unpublished observations).

Physiological significance of postsynaptic GABAB effects

We have demonstrated that activation of the GABAB receptor can inhibit the spontaneous firing of magnocellular neurones via a membrane hyperpolarization. In addition to this direct effect, other effects on the pattern of neural activity could be mediated via a GABAB-ergic hyperpolarization. Both the hyperpolarization-activated cation current (Ih) and the low threshold T-type Ca2+ current (IT) are expressed in the majority of both SON and PVN magnocellular neurones in the guinea pig, and have been shown to play an essential role in phasic burst firing in guinea pig AVP SON neurones (Erickson et al. 1990, 1993a,b). These two intrinsic currents were also present in the majority of recorded neurones in the present study (Fig. 5B). Moreover, Ih has been associated with rebound burst firing in the rat (Ghamari-Langroudi & Bourque, 2000). Since Ih requires a membrane hyperpolarization in order to be activated, and the T-current requires a hyperpolarization in order to remove inactivation of the channel, the activity of both currents could be modulated by a membrane hyperpolarization as provided by activation of the GABAB receptor. Collectively, the results from our studies would suggest a mechanism by which GABAergic input via the GABAB receptor may modulate the intrinsic currents associated with phasic burst firing in guinea pig AVP neurones (Erickson et al. 1993a,b; Fig. 9).

Summary

In summary, we have found that both GABAB-R1 and -R2 transcripts are expressed in guinea pig magnocellular AVP neurones and that GABAB receptors are coupled to inwardly rectifying K+ channels in these neurones. Activation of IK,ir hyperpolarizes SON and PVN neurones and modulates the phasic firing activity in these neurones.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by US Public Health Services Grants NS 38809, NS 35944, DA05158, and the American Heart Association, Oregon Chapter. We would like to recognize Ms Martha Bosch, Mr Jason Deignan and Mr Barry Naylor for their excellent technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- Beck SG, Birnstiel S, Pouliot WA, Choi KC. Baclofen concentration-response curves differ between hippocampal subfields. Neuroreport. 1995;6:310–312. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199501000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudaba C, Szabó K, Tasker JG. Physiological mapping of local inhibitory inputs to the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus. J Neurosci. 1996;16:7151–7160. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-22-07151.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourque CW. Osmoregulation of vasopressin neurons: A synergy of intrinsic and synaptic processes. Prog Brain Res. 1998;119:59–76. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)61562-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourque CW, Renaud LP. Electrophysiology of mammalian magnocellular vasopressin and oxytocin neurosecretory neurones. Front Neuroendocrinol. 1990;11:183–212. [Google Scholar]

- Chieng B, Christie MJ. Hyperpolarization by GABAB receptor agonists in mid-brain periaqueductal gray neurones in vitro. Br J Pharmacol. 1995;116:1583–1588. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb16376.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie MJ, North RA. Agonists at mu-opioid M2-muscarinic and GABAB-receptors increase the same potassium conductance in rat lateral parabrachial neurones. Br J Pharmacol. 1988;95:896–902. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1988.tb11719.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark JA, Mezey E, Lam AS, Bonner TI. Distribution of the GABA(B) receptor subunit gb2 in rat CNS. Brain Res. 2000;860:41–52. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)01958-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowley WR, Armstrong WE. Neurochemical regulation of oxytocin secretion in lactation. Endocr Rev. 1992;13:33–65. doi: 10.1210/edrv-13-1-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui LN, Coderre E, Renaud LP. GABA(B) presynaptically modulates suprachiasmatic input to hypothalamic paraventricular magnocellular neurones. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2000;278:R1210–1216. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.278.5.R1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decavel C, Van den Pol AN. Converging GABA- and glutamate-immunoreactive axons make synaptic contact with identified hypothalamic neurosecretory neurones. J Comp Neurol. 1992;316:104–116. doi: 10.1002/cne.903160109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson KR, Rønnekleiv OK, Kelly MJ. Inward rectification (Ih) in immunocytochemically identified vasopressin and oxytocin neurones of guinea-pig supraoptic nucleus. J Neuroendocrinol. 1990;2:261–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.1990.tb00402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson KR, Rønnekleiv OK, Kelly MJ. Electrophysiology of guinea-pig supraoptic neurones. Role of a hyperpolarization-activated cation current in phasic firing. J Physiol. 1993a;460:407–425. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson KR, Rønnekleiv OK, Kelly MJ. Role of a T-type calcium current in supporting a depolarizing potential, damped oscillations, and phasic firing in vasopressinergic guinea pig supraoptic neurones. Neuroendocrinology. 1993b;57:789–800. doi: 10.1159/000126438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Y, Rønnekleiv OK. Cocaine upregulates the dopamine transporter in fetal rhesus monkey brain. J Neurosci. 1999;19:8966–8978. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-20-08966.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghamari-Langroudi M, Bourque CW. Excitatory role of the hyperpolarization-activated inward current in phasic and tonic firing of rat supraoptic neurones. J Neurosci. 2000;20:4855–4863. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-13-04855.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gribkoff VK, Dudek FE. Effects of excitatory amino acid antagonists on synaptic responses of supraoptic neurones in slices of rat hypothalamus. J Neurophysiol. 1990;63:60–71. doi: 10.1152/jn.1990.63.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harayama N, Shibuya I, Tanaka K, Kabashima N, Ueta Y, Yamashita H. Inhibition of N- and P/Q-type calcium channels by postsynaptic GABAB receptor activation in rat supraoptic neurones. J Physiol. 1998;509:371–383. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.371bn.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermes MLHJ, Ruijter JM, Klop A, Buijs RM, Renaud LP. Vasopressin increases GABAergic inhibition of rat hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus neurones in vitro. J Neurophysiol. 2000;83:705–711. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.2.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille B. Potassium channels and chloride channels. In: Hille B, editor. Ionic Channels of Excitable Membranes. Massachusetts: Sinauer; 2001. pp. 131–162. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim N, Shibuya I, Kabashima N, Setiadji VS, Ueta Y, Yamashita H. GABAB receptor-mediated inhibition of spontaneous action potential discharge in rat supraoptic neurones in vitro. Brain Res. 1998;813:88–96. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)01009-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jhamandas JH, Renaud LP. Bicuculline blocks an inhibitory baroreflex input to supraoptic vasopressin neurones. Am J Physiol. 1987;252:R947–952. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1987.252.5.R947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jourdain P, Poulain DA, Theodosis DT, Israel JM. Electrical properties of oxytocin neurons in organotypic cultures from postnatal rat hypothalamus. J Neurophysiol. 1996;76:2772–2785. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.76.4.2772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabashima N, Shibuya I, Ibrahim N, Ueta Y, Yamashita H. Inhibition of spontaneous EPSCs and IPSCs by presynaptic GABAB receptors on rat supraoptic magnocellular neurones. J Physiol. 1997;504:113–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.113bf.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaupmann K, Malitschek B, Schuler V, Heid J, Froestl W, Beck P, Mosbacher J, Bischoff S, Kulik A, Shigemoto R, Karschin A, Bettler B. GABAB-receptor subtypes assemble into functional heteromeric complexes. Nature. 1998a;396:683–687. doi: 10.1038/25360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaupmann K, Schuler V, Mosbacher J, Bischoff S, Bittiger H, Heid J, Froestl W, Leonhard S, Pfaff T, Karschin A, Bettler B. Human γ-aminobutyric acid type B receptors are differentially expressed and regulate inwardly rectifying K+ channels. Neurobiol. 1998b;95:14991–14996. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolaj M, Yang CR, Renaud LP. Pre-synaptic GABAB receptors modulate organum vasculosum lamina terminalis-evoked postsynaptic currents in rat hypothalamic supraoptic neurones. Neuroscience. 2000;98:129–133. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00094-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kombian SB, Zidichouski JA, Pittman QJ. GABAB receptors presynaptically modulate excitatory synaptic transmission in the rat supraoptic nucleus in vitro. J Neurophysiol. 1996;76:1166–1179. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.76.2.1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagrange AH, Wagner EJ, Rønnekleiv OK, Kelly MJ. Estrogen rapidly attenuates a GABAB response in hypothalamic neurones. Neuroendocrinology. 1996;64:114–123. doi: 10.1159/000127106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legendre P, Poulain DA. Intrinsic mechanisms involved in the electrophysiological properties of the vasopressin-releasing neurones of the hypothalamus. Prog Neurobiol. 1992;38:1–17. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(92)90032-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loose MD, Rønnekleiv OK, Kelly MJ. Neurones in the rat arcuate nucleus are hyperpolarized by GABAB and μ-opioid receptor agonists. Evidence for convergence at a ligand-gated potassium conductance. Neuroendocrinology. 1991;54:537–544. doi: 10.1159/000125979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu XY, Ghasemzadeh MB, Kalivas PW. Regional distribution and cellular localization of gamma-aminobutyric acid subtype 1 receptor mRNA in the rat brain. J Comp Neurol. 1999;407:166–182. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19990503)407:2<166::aid-cne2>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luckman SM, Antonijevic I, Leng G, Dye S, Douglas AJ, Russell JA, Bicknell RJ. The maintenance of normal parturition in the rat requires neurohypophysial oxytocin. J Neuroendocrinol. 1994;5:7–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.1993.tb00358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouginot D, Kombian SB, Pittman QJ. Activation of pre-synaptic GABAB receptors inhibits evoked IPSCs in rat magnocellular neurons in vitro. J Neurophysiol. 1998;79:1508–1517. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.3.1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulain DA, Wakerley JB. Electrophysiology of hypothalamic magnocellular neurones secreting oxytocin and vasopressin. Neurosci. 1982;7:773–808. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(82)90044-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pumford KM, Russell JA, Leng G. Effects of the selective kappa-opioid agonist U50,488 upon the electrical activity of supraoptic neurones in morphine-tolerant and morphine-naive rats. Exp Brain Res. 1993;94:237–246. doi: 10.1007/BF00230291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randle JCR, Renaud LP. Actions of γ-aminobutyric acid on rat supraoptic nucleus neurosecretory neurones in vitro. J Physiol. 1987;387:629–647. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renaud LP. Magnocellular neuroendocrine neurones, update on intrinsic properties, synaptic inputs and neuropharmacology. Trends Neurosci. 1987;10:498–502. [Google Scholar]

- Richard D, Bourque CW. Synaptic control of rat supraoptic neurones during osmotic stimulation of the organum vasculosum lamina terminalis in vitro. J Physiol. 1995;489:567–577. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp021073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roland BL, Sawchenko PE. Local origins of some GABAergic projections to the paraventricular and supraoptic nuclei of the hypothalamus in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1993;332:123–143. doi: 10.1002/cne.903320109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rønnekleiv OK, Loose MD, Erickson KR, Kelly MJ. A method for immunocytochemical identification of biocytin-labeled neurones following intracellular recording. Biotechniques. 1990;9:432–438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell JA, Leng G, Bicknell RJ. Opioid tolerance and dependence in the magnocellular oxytocin system. A physiological mechanism. Exp Physiol. 1995;80:307–340. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1995.sp003850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen KZ, Johnson SW. Pre-synaptic GABAB and adenosine A1 receptors regulate synaptic transmission to rat substantia nigra reticulata neurones. J Physiol. 1997;505:153–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.153bc.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slugg RM, Fang Y, Rønnekleiv OK, Kelly MJ. Expression of GABAB receptor subunit mRNAs and activation of an inwardly rectifying K+ conductance in guinea pig paraventricular nucleus neurones. Abstr Soc Neurosci. 2000;26:1946. [Google Scholar]

- Slugg RM, Rønnekleiv OK, Grandy DK, Kelly MJ. Baclofen hyperpolarizes guinea pig supraoptic nucleus neurones by activating an inwardly-rectifying K+ conductance. Abstr Soc Neurosci. 1999a;25:702. [Google Scholar]

- Slugg RM, Rønnekleiv OK, Grandy DK, Kelly MJ. Activation of an inwardly-rectifying K+ conductance by orphanin-FQ/nociceptin in vasopressin-containing neurones. Neuroendocrinology. 1999b;69:385–396. doi: 10.1159/000054441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern JE, Li Y, Richards DS. Post synaptic GABA(B) receptors in supraoptic oxytocin and vasopressin neurons. Prog Brain Res. 2002;139:121–125. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(02)39012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasker JG, Boudaba C, Schrader LA. Local glutamatergic and GABAergic synaptic circuits and metabotropic glutamate receptors in the hypothalamic paraventricular and supraoptic nuclei. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1998;449:117–121. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-4871-3_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner EJ, Bosch MA, Kelly MJ, Rønnekleiv K. A powerful GABAB receptor-mediated inhibition of GABAergic neurones in the arcuate nucleus. Neuroreport. 1999;10:2681–2687. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199908200-00045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakerley JB, Lincoln DW. The milk-ejection reflex of the rat, a 20- to 40-fold acceleration in the firing of paraventricular neurones during oxytocin release. J Endocrinol. 1973;57:477–493. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0570477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White JH, Wise A, Main MJ, Green A, Fraser NJ, Disney GH, Barnes AA, Emson P, Foord SM, Marshall FH. Heterodimerization is required for the formation of a functional GABAB receptor. Nature. 1998;396:679–682. doi: 10.1038/25354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JT, Colmers WF, Pan ZZ. Voltage- and ligand-activated inwardly rectifying currents in dorsal raphe neurones in vitro. J Neurosci. 1988a;8:3499–3506. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-09-03499.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JT, North RA, Tokimasa T. Inward rectification of resting and opiate-activated potassium currents in rat locus coeruleus neurones. J Neurosci. 1988b;8:4299–4306. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-11-04299.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang CR, Senatorov VV, Renaud LP. Organum vasculosum lamina terminalis evoked postsynaptic responses in rat supraoptic neurones in vitro. J Physiol. 1994;477:59–74. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]