Abstract

In the ATP-dependent K+ (KATP) channel pore-forming protein Kir6.2, mutation of three positively charged residues, R50, K185 and R201, impairs the ability of ATP to close the channel. The mutations do not change the channel open probability (Po) in the absence of ATP, supporting the involvement of these residues in ATP binding. We recently proposed that at least two of these positively charged residues, K185 and R201, interact with ATP phosphate groups to cause channel closure: the β phosphate group of ATP interacts with K185 to initiate closure, while the α phosphate interacts with R201 to stabilize the channel's closed state. In the present study we replaced these three positive residues with residues of different charge, size and hydropathy. For K185 and R201, we found that charge, more than any other property, controls the interaction of ATP with Kir6.2. At these positions, replacement with another positive residue had minor effects on ATP sensitivity. In contrast, replacement of K185 with a negative residue (K185D/E) decreased ATP sensitivity much more than neutral substitutions, suggesting that an electrostatic interaction between the β phosphate group of ATP and K185 destabilizes the open state of the channel. At R201, replacement with a negative charge (R201E) had multiple effects, decreasing ATP sensitivity and preventing full channel closure at high concentrations. In contrast, the R50E mutation had a modest effect on ATP sensitivity, and only residues such as proline and glycine that affect protein structure caused major decreases in ATP sensitivity at the R50 position. Based on these results and the recently published structure of Kir3.1 cytoplasmic domain, we propose a scheme where binding of the β phosphate group of ATP to K185 induces a motion of the surrounding region, which destabilizes the open state, favouring closure of the M2 gate. Binding of the α phosphate group of ATP to R201 then stabilizes the closed state. R50 on the N-terminus controls ATP binding by facilitating the interaction of the β phosphate group of ATP with K185 to destabilize the open state.

Mutations of three positively charged residues in the KATP channel pore-forming protein Kir6.2, R50 in the N-terminus and K185 and R201 in the C-terminus, decrease ATP-induced channel inhibition. With R50 and K185 mutants, the decrease in ATP sensitivity occurred without a significant change in channel Po in the absence of ATP (Tucker et al. 1998). Since ATP binds preferentially to the channel closed state and there was no increase in Po to account for the decreased ATP sensitivity, Tucker et al. (1998) concluded that these residues are likely to be directly involved in the binding of ATP to Kir6.2. Later, Shyng et al. (2000), studying channel reactivation by phosphatidylinositol bisphosphate (PIP2), reported that the R201 mutation did not affect channel Po at zero ATP and proposed that R201 was also part of the ATP-binding site. We recently reported that K185 and R50 mutations affected primarily the sensitivity to ATP and ADP and had comparatively little effect on AMP sensitivity (Ribalet et al. 2003). Based on these observations we concluded that K185 and R50 control primarily the interaction of the β phosphate group of adenine nucleotides with Kir6.2. In contrast, the R201 mutation affected the ATP, ADP and AMP sensitivity equally, leading us to conclude that R201 interacts with the α phosphate group of adenine nucleotides or possibly the adenosine moiety (Ribalet et al. 2003).

In the same study we investigated how channel rundown due to Mg2+ removal or sulfonylurea addition affected ATP sensitivity (Ribalet et al. 2003). With the wild-type KATP channel (Kir6.2 + SUR1), fast rundown, due in part to a loss of MgADP-dependent stimulation, was accompanied by a 5- to 10-fold increase in ATP sensitivity. This result supports the hypothesis of preferential ATP binding to a closed state of the channel. Mutation of K185 and R50 did not significantly affect the increase in ATP sensitivity evoked by channel rundown, suggesting that these two residues were not part of the mechanism that stabilized the closed state in the presence of ATP. In contrast, mutation of R201, which did not prevent channel rundown, suppressed the increase in ATP sensitivity induced by rundown or sulfonylurea addition. Based on these results we proposed a model whereby interaction of the ATP β phosphate group with K185 and R50 caused destabilization of the channel open state and initiation of channel closure, while interaction of the ATP α phosphate group with R201 favoured stabilization of the closed state (Ribalet et al. 2003).

In the present study we systematically replaced R50, K185 and R201 with residues of different charge, size and hydropathy. We found that the residue's size or hydropathy had modest effects in most cases. In contrast, the effects of charge were dramatic in two cases. Inserting a negative charge at K185 decreased ATP sensitivity dramatically in comparison to neutral substitutions, while insertion of a negative residue at R201 prevented complete channel closure by ATP and even caused channel re-opening at high ADP concentrations. In contrast, insertion of a negative charge at R50 (R50E) had little effect and yielded a similar ATP sensitivity to wild-type channels.

From the recently published structure of Kir3.1 (Nishida & MacKinnon, 2002), it appears that the key residues involved in ATP binding in Kir6.2 are located on the outside of the pore-forming protein rather than within the cytoplasmic pore region. Based on the predicted structure and our findings, we propose a scheme where binding of the ATP β phosphate group to K185 destabilizes the open state, which in turn permits a tilting of M2 and transition of the channel to an unstable closed state. A change in conformation of the ATP-binding site by R50 facilitates the interaction of the β phosphate group with K185 and thus destabilization of the open state. In the unstable closed state, the α phosphate group of ATP approaches the vicinity of R201, where its electrostatic interaction stabilizes the channel in the closed state. Thus, the ATP closing mechanism may involve movement of only one or two β strands that are at the periphery of the tetramer.

METHODS

The techniques for cDNA expression and patch clamp recording have recently been described in detail (John et al. 1998) and are only briefly outlined here.

Molecular biology and cDNA expression in HEK293 cells

In many cases HEK293 cells were transfected with cDNA for Kir6.2 mutants linked to green fluorescent protein (GFP) at the C-terminus (Kir6.2-GFP) so that insertion of the constructs into the plasma membrane could be followed. Our previous findings showed that linkage to GFP did not affect the kinetics or adenine nucleotide sensitivity of wild-type Kir6.2 + SUR1 channels (John et al. 1998). All wild-type cDNAs were subcloned into the vector pCDNA3amp (Invitrogen). cDNA used to make the GFP chimeras was subcloned into the pEGFP vector (Clontech). Both vectors use the CMV promoter. Single site Kir6.2 mutations were constructed using the QuikChange technique from Stratagene (La Jolla, CA, USA). All mutants were in the Kir6.2-GFP backbone. The R201A mutant was kindly provided by Dr C. Nichols (Washington University, St Louis, MO, USA) and subcloned into the Kir6.2-GFP backbone. The transfections were carried out using the calcium phosphate precipitation method (Graham & van der Eb, 1973). Expression of proteins linked to GFP was detected as early as 12 h after transfection. Patch clamp experiments were started approximately 30 h after transfection. HEK293 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) high glucose medium supplemented with 10 % (v/v) fetal calf serum, penicillin (100 units ml−1), streptomycin (100 units ml−1) and 2 mM glutamine, and divided once a week by treatment with trypsin.

Patch clamp methods

Currents were recorded in HEK293 cells using the inside-out patch clamp configuration, with a pipette solution containing (mM): 140 KCl, 10 NaCl, 1.1 MgCl2 and 10 Hepes, pH adjusted to 7.2 with KOH. The bath solution consisted of (mM): 140 KCl, 10 NaCl, 1.1 MgCl2, 10 Hepes, 5 EGTA and 0.5 CaCl2, with pH adjusted to 7.2 with KOH. The data, filtered at 2 kHz with an 8-pole Bessel filter, were recorded with a List EPC 7 (Darmstadt, FRG) patch clamp amplifier and recorded on videotape at a fixed frequency of 44 kHz after digitization with a digital audio processor. For analysis, the data were sampled at a rate of 5.5 kHz.

ATP sensitivity measurements

Adenine nucleotides were added directly to the bath. To measure ATP sensitivity, channels were excised into Mg2+-free solution or exposed to 200 nM glybenclamide to decrease Po. As previously reported (Ribalet et al. 2003), these methods provide similar estimates of ATP sensitivity after channel rundown, with the advantage of glybenclamide allowing rapid assessment of the effects of Po on channel ATP sensitivity. The decrease in Po and increase in ATP sensitivity evoked by sulfonylureas occurs within 2 s, while rundown induced by Mg2+ removal is slow (10-30 min).

Protein structure

A protein model of the mouse Kir6.2 channel was created using mouse Kir3.1 structural coordinates reported by Nishida & MacKinnon (2002) as a template. Kir3.1 coordinates were downloaded from the Protein Database (file 1N9P). An alignment was generated between Kir3.1 and Kir6.2 using DeepView (Swiss Pdb-Viewer) (Guex et al. 1997). The sequence alignment was then submitted to SWISS-MODEL, an automated comparative protein modelling server (Appel et al. 1994), for generating the protein coordinates of Kir6.2. With a sequence identity of 47.7 % between Kir6.2 and Kir3.1 (crystallized portions), the predicted Kir6.2 structure remained very similar overall to the Kir3.1 structure, with the root mean square of the backbone 0.01 Å (1 Å = 0.1 nm) when the model included only the crystallized portions. The predicted Kir6.2 cytoplasmic pore model was viewed using DeepView, which also permitted measurement of distances between residues as well as computation of the protein electrostatic potential. The ATP coordinates were obtained from the protein database.

Modelling

Modelling of channel kinetics was carried out using SCoP version 3.5 (Simulation Resources, Inc.)

RESULTS

Systematic mutation of positive residues in the cytoplasmic N- and C-termini of Kir6.2 has identified three major ATP-binding residues: R50, K185 and R201 (Tucker et al. 1998; Shyng et al. 2000). Based on the effects of mutations of these sites on ATP, ADP and AMP sensitivities, we recently proposed that R50 and K185 interact with the β phosphate group of adenine nucleotides to destabilize the open state, while R201 interacts with the α phosphate group to stabilize the closed state (Ribalet et al. 2003). Here we investigated how the charge, size and hydropathy of these residues affect the interaction of ATP with the channel.

ATP interaction with the K185 site

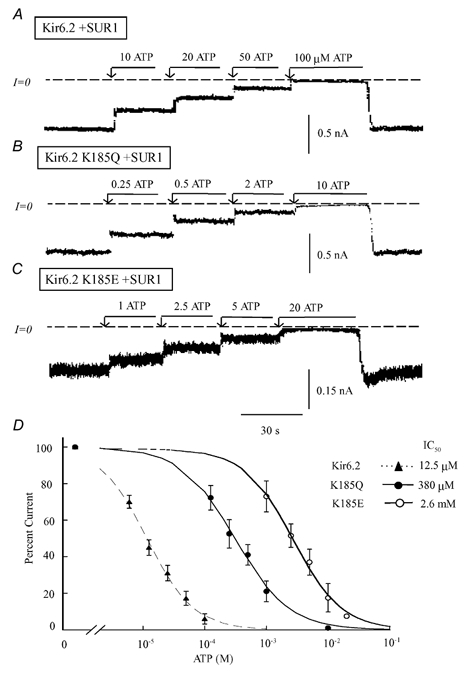

Using Kir6.2 with a 26 amino acid C-terminal deletion expressed in oocytes, Reimann et al. (1999) characterized the effects of K185 mutation on the channel ATP sensitivity. We now show data obtained with full length Kir6.2 mutants co-expressed with the sulfonylurea receptor SUR1 in the mammalian cell line HEK293. With and without SUR1, the K185 mutations in Kir6.2 had similar effects, as depicted in Fig. 1 and shown in Table 1. In the absence of Mg2+, the ATP sensitivity of wild-type Kir6.2 + SUR1 was approximately 7-fold higher than that of Kir6.2 alone. Thus, the IC50 for inhibition by ATP was 85 μM for Kir6.2 alone and 12.5 μM for Kir6.2 + SUR1 (ratio 6.8) (see Fig. 1). A similar ratio was obtained for all K185 mutations tested (Table 1). For Kir6.2 K185R and K185E, the IC50 values without and with SUR1 were 183 and 28 μM (ratio 6.5), and 20 and 2.6 mM (ratio 7.7), respectively. From these data it may be concluded that the positively charged residue arginine is a good substitute for lysine at position 185. In contrast, substituting the negatively charged residues aspartate or glutamate for lysine had opposite effects and dramatically decreased ATP-dependent inhibition.

Figure 1. ATP sensitivity of K185X mutants co-expressed with SUR1.

Current traces in the three upper panels depict inward currents measured in the absence of Mg2+, for wild-type Kir6.2 channels co-expressed with SUR1 (A) and for two Kir6.2 mutants, K185Q (B) and K185E (C) also co-expressed with SUR1. Currents were progressively suppressed by increasing ATP concentration, with the IC50 near 12 μM, 0.4 mM and 2.5 mM, respectively. On average K185 replacement with neutral residues had a modest effect on ATP-induced inhibition, while replacement with negatively charged residues dramatically decreased ATP sensitivity. C, plot of channel ATP sensitivity for wild-type Kir6.2 (▴), K185Q (•) and K185E (○), all co-expressed with SUR1. A fit of the data points to the Hill equation yielded IC50 values of 12.5 μM (n = 5) for wild-type channels, 0.38 mM (n = 5) for K185Q and 2.6 mM (n = 3) for K185E. The three Hill coefficients were close to unity.

Table 1.

ATP sensitivity of Kir6.2 mutants (R50X, K185X and R201X) + SUR1

| Amino acid sustitute | ATP IC50 (μm) | Hydropathy | Size indexed to R | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | — | 12.5 ± 3 | — | — |

| R201 | K | 140 ± 54 | −3.9 | 0.8 |

| E | 193 ± 130 | −3.5 | 0.7 | |

| Q | 780 | −3.5 | 0.7 | |

| V | 981 ± 189 | 4.2 | 0.7 | |

| D | * | −3.5 | 0.5 | |

| A | 820 ± 175 | 1.8 | 0.4 | |

| G | 2180 ± 330 | −0.4 | 0.3 | |

| R50 | K | 61 ± 32 | −3.9 | 0.8 |

| E | 22.5 ± 7.5 | −3.5 | 0.7 | |

| Q | 119 ± 12 | −3.5 | 0.7 | |

| V | 203 ± 63 | 4.2 | 0.7 | |

| D | 67 ± 22 | −3.5 | 0.5 | |

| A | 136 ± 37 | 1.8 | 0.4 | |

| G | 1275 ± 195 | −0.4 | 0.3 | |

| P | 12 500 ± 2500 | −1.6 | 0.6 | |

| K185 | R | 27.5 ± 14 | −4.5 | 1 |

| E | 2600 ± 960 | −3.5 | 0.7 | |

| Q | 385 ± 75 | −3.5 | 0.7 | |

| V | 475 ± 55 | 4.2 | 0.7 | |

| D | 1900 ± 750 | −3.5 | 0.5 | |

| A | 82.5 ± 22 | 1.8 | 0.4 | |

| G | 35.5 ± 9 | −0.4 | 0.3 |

ATP sensitivity of Kir6.2 mutants (R50X, K185X and R201X) + SUR1, showing how mutaions affect ATP IC50. Each value is an average of 3−6 measurements carried out in separate patches, except for the R201Q mutant where only 2 measurements were successfully obtained. In the case of R201D, the asterisk indicates that the mutation yielded no functional channels due to a failure to insert into the plasma membrane. In general the IC50 values reported in this table are similar to those reported previously (Ribalet et al. 2003) for the same mutants, with the exception of R201E (see Methods). However, small differences exist due to additional experiments performed since the submission of our 2003 publication. The IC50 value for R50P is shown in italics because in this case the ATP sensitivity had to be deduced from the [ATP] vs. channel activity plot when ATP concentrations were less than 10 mm. The hydropathy values are from Kyte & Doolittle (1982) (negative values indicate hydrophilic). The numbers in the last column illustrate the length of the residue's side chain indexed to that of arginine.

The comparison of K185Q and K185V indicates that hydropathy is not a major factor in controlling ATP affinity at this position. Indeed, the two residues are at the opposite ends of the hydropathy spectrum, yet caused similar shifts in ATP sensitivity (with IC50 values of 385 and 475 μM, respectively). In contrast, amino acids with small side chains substituted more effectively than amino acids with larger side chains (see size index in Table 1). For example, replacement of K185 with glycine or alanine, with small side chains, had only a modest effect on ATP sensitivity (IC50 35.5 and 82.5 μM, as compared to 12.5 μM for wild-type channels), whereas replacement of K185 with glutamine or valine, with larger side chains, shifted the ATP sensitivity to 385 and 475 μM, respectively.

In summary, the presence of a positive charge at position 185 plays a major role with respect to the interaction of ATP with Kir6.2, and more precisely for the interaction of the β phosphate group with this site (Ribalet et al. 2003). Small residues at this position had less effect on ATP sensitivity than larger residues, suggesting that the binding of the β phosphate group to K185 may be stabilized by interactions with other residues near K185, since ATP still bound with relatively high affinity (≈3-fold lower than wild-type) when the positive charge at K185 was neutralized.

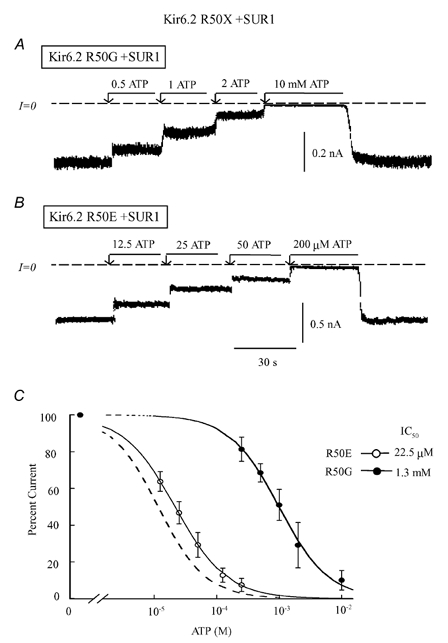

ATP interaction with the R50 site

In 1999 Proks et al. suggested that arginine at position 50 is unlikely to contribute directly to the binding of ATP to Kir6.2, but may affect ATP inhibition by allosteric interactions. To test this hypothesis, we systematically mutated R50 to residues of different charge, size and hydropathy. The main findings are illustrated in Fig. 2 and Table 1. The R50 mutations had very different effects from the K185 mutations on ATP sensitivity. Specifically, insertion of a negatively charged glutamate or aspartate at position 50 had very modest effects on ATP sensitivity (with IC50 values of 22.5 and 67 μM, respectively), comparable to inserting the positively charged lysine residue (R50K), which decreased the IC50 5-fold to 61 μM. This result suggests that specific interaction of the ATP phosphate group with R50 is not necessary to promote channel closure. However, a role for a negative charge from a glutamate or a phosphate group interacting with R50 exists, since replacement with the neutral glutamine (R50Q), a residue with similar hydropathy and size to arginine, caused a greater (10-fold) decrease in ATP sensitivity compared to the positively or negatively charged substitutions. In addition, the hydropathy or size of the residue at position 50 did not appear to play a major role. Thus, replacement with glutamate or glutamine, which have comparable hydropathy and size, had significantly different effects on ATP sensitivity, with IC50 values of 22.5 and 120 μM, respectively.

Figure 2. ATP sensitivity of R50X mutants co-expressed with SUR1.

Current traces in A and B illustrate inward currents measured in the absence of Mg2+, for Kir6.2 mutants R50G (A) and R50E (B), both co-expressed with SUR1. These panels depict progressive suppression of inward current by increasing ATP concentration, with the IC50 values near 22 μM and 1.3 mM, respectively. R50G had major effects on ATP sensitivity, while R50E had little effect. C, plot of channel ATP sensitivity for R50G (•) and R50E (○) co-expressed with SUR1, with the wild-type curve indicated by the dashed line for comparison. A fit of the data points to the Hill equation yielded IC50 values of 1.3 mM (n = 5) for R50G channels and 22.5 μM (n = 5) for R50E. The two Hill coefficients were close to unity.

The most dramatic decrease in ATP sensitivity observed with R50 mutations occurred with replacement by glycine and proline. The IC50 of R50G and R50P increased to 1.3 and 12 mM, respectively, contrasting with K185G whose ATP sensitivity remained close to that of wild-type channels. However, alanine, which has similar size and hydropathy characteristics to glycine, had a much more modest effect (IC50 136 μM), indicating again that the effects of glycine were not directly related to its size or hydropathy. We hypothesize that the low ATP sensitivity observed with R50G and R50P may be due to the known effects of these residues in disrupting the protein structure sufficiently to prevent an interaction between the N- and C-termini that destabilizes the channel open state.

In summary, replacement of the R50 residue with a negative charge suggests that the presence of the ATP molecule at R50 is not necessary for ATP-dependent gating. The situation is distinctly different from that for K185, where a negative charge could not substitute for the phosphate group interaction and the presence of the ATP molecule appeared to be essential to initiate ATP-dependent gating.

ATP interaction with the R201 site

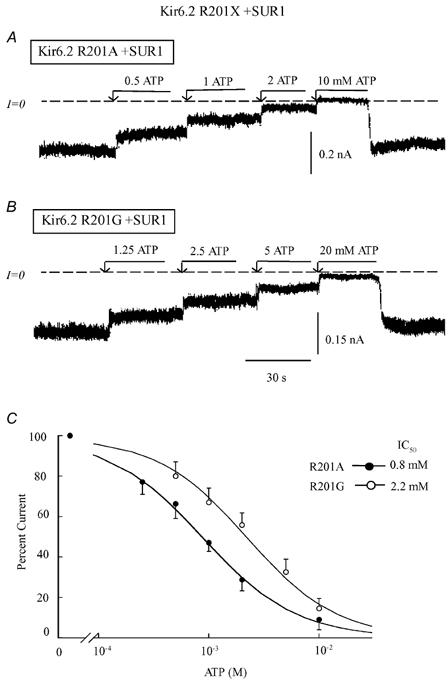

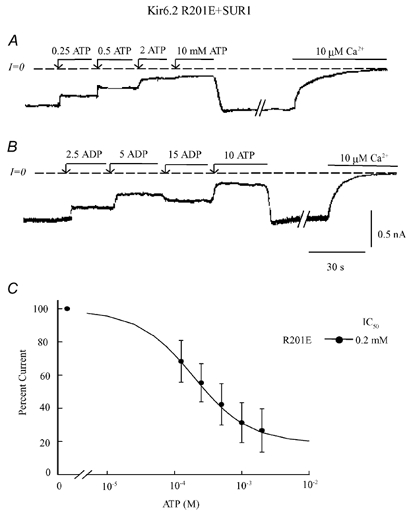

Interaction of R201 with ATP phosphate groups was first suggested by Shyng et al. (2000). We subsequently refined this hypothesis by proposing that R201 interacted specifically with the α phosphate group of ATP to stabilize the closed state (Ribalet et al. 2003). Consistent with the report of Shyng et al. (2000), we found using single channel recording that R201A channels without SUR1 did not increase Po in the absence of ATP (data not shown). However, data presented in Fig. 3 and Fig. 4 and summarized in Table 1 indicate that the mutations at site 201 had generally potent effects at decreasing ATP sensitivity. Only R201K and R201E had modest effects on the IC50 (140 and 193 μM, respectively), but R201E channel activity could not be suppressed fully by up to 10 mM ATP (see below). As previously reported, the neutral R201 mutations showed no increase in ATP sensitivity when the channels ran down, but this was not true for either R201K (as would be expected) or R201E. This is the explanation for the higher ATP sensitivity for R201E reported here than in our previous paper (Ribalet et al. 2003), in which the ATP sensitivitiy of R201E was reported to be ≈1.4 mM prior to fast rundown. All other mutants yielded IC50 values near or greater than 1 mM after fast rundown, suggesting that a positively charged residue at this location plays an important role in ATP-dependent channel closure.

Figure 3. ATP sensitivity of R201X mutants co-expressed with SUR1.

Current traces in A and B depict inward currents measured in the absence of Mg2+ with Kir6.2 mutants, for R201A (A) and R201G (B) co-expressed with SUR. These panels illustrate progressive suppression of inward current by increasing ATP concentrations with the IC50 values near 0.8 mM and 2.2 mM, respectively. R201A had substantial effects on ATP sensitivity, while R201G, which may modify the protein structure, had an even larger effect. C, plot of channel ATP sensitivity for R201A (•) and R201G (○) co-expressed with SUR1. A fit of the data points to the Hill equation yielded IC50 values of 0.8 mM (n = 5) for R201A channels and 2.2 mM (n = 3) for R201G. The two Hill coefficients were close to unity.

Figure 4. ATP and ADP sensitivity of R201E co-expressed with SUR1.

Current traces in A and B depict inward currents measured in the absence of Mg2+ with the Kir6.2 mutant R201E + SUR1. These panels illustrate progressive suppression of inward current by increasing concentrations of ATP (A) and ADP (B). At the end of each trace, full current inhibition by Ca2+ is shown to illustrate that ATP or ADP failed to fully suppress channel activity. With high ADP there was even channel re-opening (B). C, plot of channel ATP sensitivity for R201E (•) co-expressed with SUR1. For this plot three patches were selected to illustrate the wide difference in ATP sensitivity among patches. A fit of the data points to the Hill equation was poor unless a pedestal of non-suppressible current was included, with a maximum inhibition by ATP of 81 %, IC50 of 197 μM (n = 3) and Hill coefficient close to unity.

As shown in Fig. 4, the R201E mutation prevented complete channel closure by ATP up to the highest concentration tested (10 mM). In some instances, we observed that inhibition was even partially relieved by high ATP concentrations (> 5 mM). This effect was more noticeable when the channel was blocked by ADP instead of ATP, as shown in Fig. 4B. In this example, inhibition reversed at 15 mM, leading to channel re-opening. These results support a critical role for the positive charge at R201 interacting with the ATP α phosphate group to stabilize ATP-dependent channel closure. Insertion of negatively charged residues at this position interferes with the stabilization of the closed state, presumably because of charge-charge repulsion with the ATP α phosphate group when the ATP β phosphate group is interacting with K185. Unfortunately, Kir6.2 R201D mutant channels did not traffic properly to the plasma membrane, and so we could not confirm whether this mutation has the same effect.

Our data also indicate that residue size or hydropathy characteristics at position 201 do not play a main role in stabilizing ATP-dependent channel closure. Mutation of R201 to glutamine, which, like charged residues, is strongly hydrophilic, dramatically decreased the ATP sensitivity (IC50 800 μM). R201A and R201V, whose side chain sizes vary by almost 2-fold, had almost identical effects on ATP sensitivity (IC50 values near 900 μM).

Together with our previous observations (Ribalet et al. 2003), these data suggest that the ATP α phosphate group interacts with R201 via charge-charge attraction to stabilize channel closure. As with K185, but in contrast to R50, interaction with the ATP phosphate group is specifically required for ATP-dependent channel closure.

Effects of charge substitution on Kir6.2 + SUR1 insertion into the plasma membrane

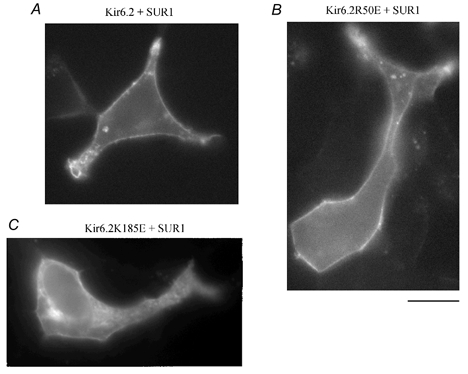

Our data indicate that negatively charged residues at position 50, but not at positions 185 or 201, can substitute for ATP phosphate group interaction with the positively charged residues. Figure 5 shows that these mutations also had different effects on trafficking to the plasma membrane. When co-expressed with SUR1, the R50E mutant linked to GFP (Fig. 5B) behaved similarly to wild-type Kir6.2 (Fig. 6A), demonstrating strong plasma membrane labelling. Currents recorded under these conditions were also similar in amplitude to wild-type Kir6.2 + SUR1 currents, suggesting that the mutant channels were equivalently inserted into the plasma membrane. In contrast, the K185E, K185D and R201D mutations had profound effects on channel insertion into the plasma membrane, as illustrated in Fig. 5C for K185E co-expressed with SUR1. Most of the labelling remained associated with intracellular membranes, possibly the endoplasmic reticulum. Under these conditions, the currents recorded in excised patches were only a fraction of the currents measured with the wild-type channel. With R201D, plasma membrane labelling was not observed and currents could not be recorded, suggesting that this mutation had dramatic effects on channel trafficking.

Figure 5. Plasma membrane insertion of Kir6.2 wild-type, R50E and K185E mutants linked to GFP and co-expressed with SUR1.

Three images obtained from different transfection experiments are representative of the distribution of GFP linked to the Kir6.2 C-terminus of Kir6.2 + SUR1, R50E + SUR1 and K185E + SUR1. A and B, data obtained with wild-type Kir6.2 and R50E showed bright uniform fluorescence associated with the plasma membrane and minimal labelling of intracellular lamellar structures. These patterns, together with the high level of channel activity recorded in both cases, support our hypothesis that R50E mutant channels behave like wild-type channels. Similar results were obtained with R201E, but not R201D. C, with K185E and K185D (not shown) fluorescence labelling of an intracellular lamellar structure tentatively identified as the endoplasmic reticulum was observed together with some plasma membrane labelling. The reduced currents recorded in these cases suggest that channel insertion into the cell membrane is partly impaired. Scale bar is 10 μm.

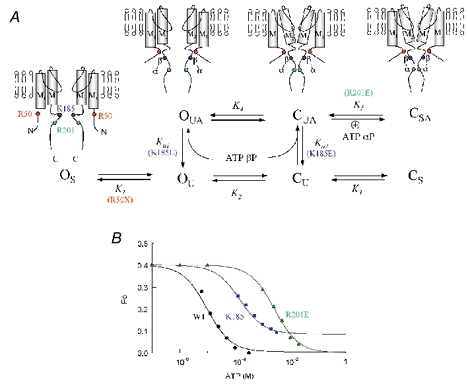

Figure 6.

A, allosteric model for the interaction of the α and β phosphate groups of adenine nucleotides with positively charged residues in Kir6.2. In the stable channel open configuration (OS), the lack of interaction between the R50 region in the N-terminus and the C-terminus does not permit binding of the ATP β phosphate with K185. Thus, R50 mutations with structure-breaking residues proline or glycine prevent this transition from OS to the unstable open state (OU), but otherwise the R50 site is relatively insensitive to charge, hydropathy or side chain size. The interaction between the R50 and K185 regions destabilizes the open state causing a transition to OU, in which interaction of the β phosphate group with K185 is permissive (OUA). Destabilization of the open state leads to unstable closure of the channel gate within M2 (CU), and binding of the ATP β phosphate to K185 allosterically promotes the transition from CU to CUA. Thus, in this model binding of the ATP β phosphate to K185 is state independent. Charge reversal at K185, however, prevents the ATP β phosphate from binding to K185, and therefore inhibits the latter transition, markedly suppressing ATP-dependent inhibition. Finally, once the channel is in the CUA state, the ATP α phosphate group interacts with R201 to stabilize the channel in a stable closed state (CSA). Insertion of a negatively charged residue at position 201 repels the approaching α phosphate group during channel closure, accounting for incomplete suppression of channel activity by ATP, since the channel can never reach the stable closed state CS. B, fitting results of the model in A to the steady-state ATP sensitivity curves for wild-type Kir6.2 (black), K185E (blue) and R201E (green). The Po in the absence of ATP was assumed to be 0.4 in each case. Fitting of this Po value in the absence of ATP yielded K1 = 2.7, K2 = 1.92 and K3 = 0.07. Fitting of the ATP dose-response curves yielded the following parameter values. For wild-type channel K5 = 16, Ka1 = 2000 and Ka2 = 11 000. For K185E mutant channels ATP binding to K185 varied yielding Ka1 = 5 and Ka2 = 40. To fit the R201E mutant data we only removed the last transition to CSA (K5 = 0).

In summary, a negative charge at position 50 has little effect on channel structure, ATP-dependent gating and trafficking, with mutant channels behaving like wild-type channels. In contrast, negative charges at positions 185 or 201 have profound effects on channel structure and ATP-dependent gating, and are also defective in trafficking.

DISCUSSION

It has been suggested that the positively charged residues R50 on the N-terminus and K185 and R201 on the C-terminus of Kir6.2 are directly involved in ATP binding via charge-charge interaction (Tucker et al. 1998; Shyng et al. 2000; Ribalet et al. 2003). We have carried out systematic replacement of these residues with residues of different charge, size and hydropathy. Our results obtained with K185 + SUR1 are consistent with the data of Reimann et al. (1999) obtained with a truncated form of Kir6.2 expressed alone, and show that negatively charged substitutions at position 185 dramatically decreased ATP-dependent inhibition, while a positively charged substitution had minor effects. In 1999 Reimann et al. observed that the K185Q mutation had similar effects on ATP and ADP sensitivity and concluded that K185 did not interact with the γ phosphate group of ATP. With Kir6.2 alone, they could not assess the very low AMP sensitivity of the Kir6.2 K185Q mutant and could not draw any conclusions regarding direct interactions of specific ATP phosphate groups with K185. The adenine nucleotide sensitivity of Kir6.2 + SUR1 is approximately 8-fold higher than that of Kir6.2 alone, however, which allowed us to compare the AMP, ADP and ATP sensitivity of wild-type and mutant Kir6.2 channels co-expressed with SUR1 (Ribalet et al. 2003). With this approach, we found that the K185Q mutation primarily affected the ability of ATP and ADP to block the channel, but not that of AMP. Thus, we hypothesized that the β phosphate group of adenine nucleotides interacts at K185. In the same study we investigated the inhibitory effects of AMP, ADP and ATP on R50G and R201A Kir6.2 channel mutants co-expressed with SUR1 (Ribalet et al. 2003). Based on the finding that mutation of R50 primarily affected ATP and ADP sensitivity, while mutation of R201 decreased the channel sensitivity to all three adenine nucleotides, we postulated that R50 primarily controlled binding to the β phosphate group of ATP, like K185, whereas R201 interacted with the α phosphate group. However, as previously mentioned (Ribalet et al. 2003), based on our data, we do not rule out that R201 may interact with the adenosine moiety of ATP rather than the α phosphate group. Furthermore, based on the observation that adenine nucleotide sensitivity increased when Po decreased in the R50G and K185Q mutants, but not in the R201C mutant, we proposed that a state-independent interaction of the β phosphate group of ATP near R50 and K185 destabilizes the open state of the channel, whereas interaction of the α phosphate group of ATP with R201 binds only to the closed state, thereby stabilizing it.

In the present study, we further investigated the interaction of ATP with R50, K185 and R201 by changing the charge, size and hydropathy of these residues. Some mild effects of residue size and possibly hydropathy on ATP sensitivity were observed, particularly at position 185, but these effects were modest compared to the effects of charge reversal. Charge effects at the three sites were different. Substitution of a negatively charged residue at position R50 had little effect on ATP sensitivity, while neutral residues significantly decreased ATP sensitivity. In contrast, insertion of negatively charged residues at positions K185 and R201 dramatically decreased ATP sensitivity, suggesting that binding of ATP phosphate groups was specifically required to promote channel closure.

Based on these observations we propose the model shown in Fig 6A. In this model, the R50 and K185 regions move independently in the absence of ATP, favouring the non-interacting stable open state OS. The conformation of the channel in which the R50 and K185 regions are closer together favours a more unstable open state (OU), which is permissive for binding of the ATP β phosphate group to K185 (the OUA state). In the OUA conformation, the open state is unstable, and allows for the movement of the M2 segment to induce channel closure to an unstable closed state (CUA). In accordance with our previous work (Ribalet et al. 2003), ATP binds to K185 in a state-independent fashion and thus can interact with OU as well as CU. Once in the CUA state, the region near R201 is now close enough to K185 to allow electrostatic interaction with the ATP α phosphate group, which stabilizes the closed state (CSA). Reversal of the charge at position 201 does not allow the channel to be stabilized in the CSA state, consistent with the inability of ATP or ADP to completely close the channel. (That is, at saturating ATP concentrations, in which all the K185 sites are occupied by β phosphate groups of ATP molecules, channel Po is determined by the final ratio of the forward to backward rate constants for the OUA⇌ CUA transition, as the channel cannot make the transition from CUA to CSA with a negative charge at 201. Further increases in cytoplasmic [ATP] have no effect, since all the K185 sites are already saturated by ATP β phosphate groups.) Figure 6B shows that the reaction scheme in Fig. 6A provides excellent quantitative fits for the ATP sensitivities of the wild-type and K185E and R201E mutants, including the component of ATP-insensitive residual current for R201E.

In this model, the transition of the channel to the closed states is allosterically promoted by the interaction of K185 with the ATP β phosphate group, and of R201 with the ATP α phosphate group. This is not true for R50, however. The role of R50 can be understood as follows: under normal conditions, a region of the N-terminus including R50 comes near the C-terminus and changes the protein conformation around K185 to facilitate binding of the ATP β phosphate group to K185, promoting destabilization of the open state. We hypothesize that most mutations at R50 do not disrupt the structure of the N-terminus sufficiently to interfere with this interaction, whereas replacement with structure-breaking glycine or proline residues does disrupt this process, trapping the channel preferentially in the stable open state (OS).

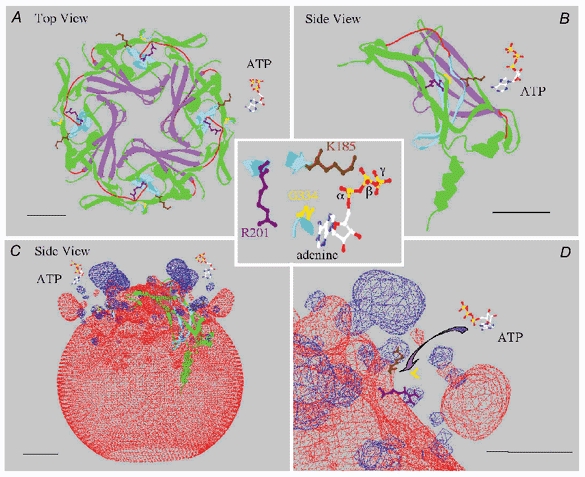

Using as a template the recent 3D structure of the cytoplasmic domain of Kir3.1, which is believed to represent an open state of the channel (Nishida & MacKinnon, 2002), we have obtained the predicted structure for the cytoplasmic pore domain of mouse Kir6.2, at an estimated 1.8 Å resolution (Fig. 7). The predicted secondary and tertiary structure are quite similar to the Kir3.1 cytoplasmic pore structure. Thus, the pore is lined by a β sheet comprising four to five β strands, with K185 and R201 located on two anti-parallel sets of β strands which are parallel to the β sheet lining the pore. In this structure, R201 and K185 are on the same horizontal plane, but their side chains point away from the channel pore. This suggests that the ATP molecule binds towards the outside of the protein away from the pore. Looking at the protein electrostatic environment (Fig. 7C and D), it can be seen that the bulk of the protein is electronegative, but near the top of each Kir6.2 subunit there is a small pocket where the negative field collapses and where two positive regions emerge corresponding to K185 and R201. These structural features are consistent with the negatively charged ATP molecule binding to the outside of the channel in the positive electrostatic pocket formed by these two residues. The location of R50 is not identified in this structure (nor in Kir3.1), but from the position of the N-terminus in the proposed structure, it is plausible that R50 could approach close to K185.

Figure 7. Structure of mouse Kir6.2 ATP-binding region.

A, view of the predicted ribbon structure of Kir6.2 cytoplasmic ‘pore’ region formed by the four subunits, viewed from the top down (towards the cytoplasm), along with an ATP molecule to the right. The purple structure delineates the pore-lining residues, and the pale blue structure corresponds to two anti-parallel sets of β strands containing residues K185 and R201, whose side chains are coloured brown and purple, respectively. The remainder of the protein is coloured green and red. Red identifies regions that differ structurally from the Kir3.1 channel or have insufficient electron density, as determined by Nishida & MacKinnon (2002), to place in a defined secondary structure. These regions are part of the linker region between the N-terminus and the C-terminus (see Nishida & MacKinnon, 2002). The cytoplasmic pore is formed by four identical subunits. B, side view of a single subunit, with an ATP molecule at the upper right, showing a detailed view of the β strands that bind ATP. C, side view of the electrostatic fields around the Kir6.2 tetramer. The negative fields are red and positive fields are blue. At the top (near the membrane), two small blue regions are formed by K185 and R201, and the larger blue region corresponds to a positive field generated by the juxtaposition of R206 and R177, which have been shown to interact with PIP2 in the plasma membrane to stabilize the channel structure. D, enlargement of the ATP-binding region, which shows the two positive residues K185 and R201 as well as G334 in yellow, on a set of β strands that face the ATP-binding region. The G334D mutation causes a 1000-fold decrease in ATP sensitivity (Drain et al. 1998). These observations suggest that ATP may bind in a pocket with the phosphate groups interacting with the positive charges at K185 and R201, while the adenine ring interacts via hydrogen bonds with G334. The estimated distance between G334 and K185 (≈8 Å) is consistent with this possibility, but the distance between the K185 and R201 side chains (≈16 Å), is very likely to be too large for the β and α phosphate groups of ATP to bind simultaneously to K185 and R201, respectively, in the purported open channel configuration shown here. We tentatively speculate that a movement (rotation) of K185 bound to the β phosphate, possibly together with G334 bound to adenine, may allow simultaneous binding of the two phosphate groups to K185 and R201. This scheme puts torsion in the side chain of 185 that may affect the backbone and hence the position of M2 to enable gating of the channel in the presence of ATP. In each panel the bar represents a distance of 10 Å.

In the channel structure shown in Fig 7, the 16 Å distance between K185 and R201 is too great to support simultaneous interaction of the β phosphate group of the ATP molecule with K185 and of the α phosphate group with R201. However, since this model (Nishida & MacKinnon, 2002) purportedly represents the open state of the channel (Os in Fig. 6), it follows from our proposed scheme that the two phosphate groups should not be interacting simultaneously with K185 and R201 in the open configuration. We speculate that upon interaction of the ATP β phosphate with K185, a twisting motion of the nearby β strands may occur that brings K185 and R201 close enough (within 9 Å) for R201 to interact with the α phosphate group of the same ATP molecule, thereby stabilizing the closed state (Cs in Fig. 6). Since the β strands associated with K185 are linked to the M2 segment, the simplest conjecture, based on the closure of CNG channels by cyclic nucleotides (Johnson & Zagotta, 2001), is that the motion due to ATP binding to this structure is transduced to the M2 segment, which then tilts and closes the pore. Validation of this model for ATP-dependent closure will have to await structural information about the closed state of Kir6.2.

Note added in proof

Since this work was submitted for publication, S. Trapp, S. Haider, P. Jones, M. S. Sansom & F. M. Ashcroft have reported independent evidence that K185 interacts with the ATP β phosphate and may approach R50 upon ATP binding (EMBO J22, 2903–2912 (2003)).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants R37HL60025 and NIH SCOR in Sudden Cardiac Death P50 HL52319, and Laubisch and Kawata Endowments to J.N.W., and by a Grant-in-Aid from the American Heart Association (Western States Affiliate) to S.A.J.

REFERENCES

- Appel RD, Bairoch A, Hochstrasser DF. A new generation of information retrieval tools for biologists: the example of the ExPASy WWW server. Trends Biochem Sci. 1994;19:258–260. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(94)90153-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drain P, Li L, Wang J. KATP channel inhibition by ATP requires distinct functional domains of the cytoplasmic C terminus of the pore forming subunit. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:13953–13958. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham FL, van der Eb AJ. Transformation of rat cells by DNA of human adenovirus 5. Virology. 1973;52:456–467. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(73)90163-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guex N, Peitsch MC. SWISS-MODEL and the Swiss-PdbViewer: An environment for comparative protein modeling. Electrophoresis. 1997;18:2714–2723. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150181505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John SA, Monck JR, Weiss JN, Ribalet B. The sulfonylurea receptor SUR1 regulates ATP-sensitive mouse Kir6. 2 K channels linked to the green fluorescent protein in human embryonic kidney cells (HEK 293) J Physiol. 1998;510:333–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.333bk.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JP, Zagotta WN. Rotational movement during cyclic nucleotide-gated channel opening. Nature. 2001;412:917–921. doi: 10.1038/35091089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyte J, Doolittle RF. A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein. J Mol Biol. 1982;157:105–132. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(82)90515-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishida M, MacKinnon R. Structural basis of inward rectification: Cytoplasmic pore of the G protein-gated inward rectifier GIRK1 at 1. 8Å resolution. Cell. 2002;111:957–965. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01227-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proks P, Gribble FM, Adhikari R, Tucker ST, Ashcroft FM. Involvement of the N terminus of Kir6. 2 in the inhibition of the KATP channel by ATP. J Physiol. 1999;514:19–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.019af.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribalet B, John SA, Weiss JN. Molecular basis for Kir6. 2 channel inhibition by adenine nucleotides. Biophys J. 2003;84:266–276. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74847-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimann F, Ryder TJ, Tucker SJ, Ashcroft FM. The role of lysine 185 in the Kir6. 2 subunit of the ATP-sensitive channel in channel inhibition by ATP. J Physiol. 1999;520:661–669. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.00661.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shyng S-L, Cukras CA, Hardwood J, Nichols CG. Structural determinant of PIP2 regulation of inward rectifier KATP channels. J Gen Physiol. 2000;116:599–607. doi: 10.1085/jgp.116.5.599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker SJ, Gribble FM, Proks P, Trapp S, Ryder TJ, Haug T, Reimann F, Ashcroft FM. Molecular determinant of KATP channel inhibition by ATP. EMBO J. 1998;17:3290–3296. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.12.3290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]