Abstract

ATP is involved in central respiratory control and may mediate changes in the activity of medullary respiratory neurones during hypercapnia, thus playing an important role in central chemoreception. The main objective of this study was to explore further the role of ATP-mediated signalling in respiratory control and central chemoreception by characterising the profile of the P2X receptors expressed by physiologically identified respiratory neurones. In particular we determined whether respiratory neurones in the rostral ventrolateral medulla (VLM) express P2X2 receptor subunits of the ATP-gated ion channel, since ATP currents evoked at recombinant P2X2 receptors are potentiated by lowering extracellular pH. Experiments were performed on anaesthetised (pentobarbitone sodium 60 mg kg−1 I.P., then 10 mg kg−1 I.V. as required), gallamine-triethiodide-treated (10 mg kg−1 I.V., then 2-4 mg kg−1 h−1 I.V.) and artificially ventilated rats. The VLM respiratory neurones were classified according to the timing of their discharge pattern in relation to that of the phrenic nerve and by the exclusion of pump cells from the study population; these were labelled with Neurobiotin using the juxtacellular method, and visualised with fluorescence microscopy. It was found that a substantial proportion of the VLM respiratory neurones express the P2X2 receptor subunit. P2X2 receptor subunit immunoreactivity was detected in ≈50 % (six out of 12) of expiratory neurones and in ≈20 % (two out of 11) of neurones with inspiratory-related discharge (pre-inspiratory and inspiratory). In contrast, no Neurobiotin-labelled VLM respiratory neurones (n = 19) were detectably immunoreactive for the P2X1 receptor subunit. Microionophoretic application of ATP (0.2 m, 20−80 nA for 40 s) increased the activity of ≈80 % (13 out of 16) of expiratory neurones and of ≈30 % (five out of 18) of VLM neurones with inspiratory-related discharge. These effects were abolished by the P2 receptor blocker suramin (0.02 M, 80 nA), which also reduced the baseline firing in some expiratory neurones. These data indicate that modulation of P2X2 receptor function, such as that evoked by acidification of the extracellular environment during hypercapnia, may contribute to the changes in activity of the VLM respiratory neurones that express these receptors.

The ventrolateral medulla (VLM) contains a network of respiratory neurones (within the caudal and rostral ventral respiratory groups and Bötzinger and pre-Bötzinger complexes) that are responsible for the generation and shaping of respiratory rhythm, as well as pre-motor neurones that are responsible for transmitting this rhythm to the spinal motoneurons controlling the diaphragm and intercostal muscles (Richter, 1982; Richter et al. 1992; Duffin et al. 1995; McCrimmon et al. 2000; Richter & Spyer, 2001). The VLM also functions as a primary central chemoreceptive area, and is responsible for sensitivity to increases in arterial levels of PCO2 and mediating the ventilatory response to hypercapnia (Loeschcke, 1982; Ballantyne & Scheid, 2000). Although other regions of the brainstem have been reported to be chemoreceptive (Nattie, 1999), it is believed that the VLM is particularly significant in mediating hypercapnia-induced respiratory responses, since neither the pons nor the dorsal medulla are required to generate CO2-sensitive respiratory rhythm (Ballantyne & Scheid, 2000). There is growing evidence that some VLM neurones displaying rhythmic respiratory-related activity are also intrinsically sensitive to changes in PCO2 (Kawai et al. 1996; Ballantyne & Scheid, 2000, 2001). It is the changes in local [H+] that follow changes in PCO2 that are thought to represent an adequate stimulus for the central chemosensitive neurones (Cherniack, 1993; Ritucci et al. 1998). However, the mechanisms underlying the chemosensitivity of these neurones remain largely unknown.

Recent data indicate that extracellular ATP acting via P2 receptors may be involved in the control of respiration at the VLM level and play an important role in central CO2 chemoreception (for a review, see Spyer & Thomas, 2000). Increases in respiration in response to rising levels of CO2 in the inspired air are attenuated by the P2 receptor antagonist suramin when microinjected into the rostral VLM (Thomas et al. 1999). Furthermore, microionophoretic application of the P2 receptor antagonists suramin or pyridoxal-5′-phosphate-6-azophenyl-2′,4′-disulphonic acid (PPADS) reduces the baseline firing and completely blocks hypercapnia-evoked increases in the activity of VLM neurones with inspiratory-related discharge, both pre-inspiratory and inspiratory (Thomas & Spyer, 2000). This suggests that these neurones are under tonic ATP-induced excitation mediated by certain P2 receptors and that this excitation is involved in the increases in their activity that occur during hypercapnia.

P2X receptors are ATP-gated cation channels that are permeable to sodium, potassium and calcium ions (Ralevic & Burnstock, 1998). Seven P2X receptor subunits (P2X1 –P2X7) have been cloned and characterised in terms of their agonist/antagonist selectivity (Buell et al. 1996; Ralevic & Burnstock, 1998). Since one pertinent feature of P2X receptors is that their sensitivity to ATP is modulated by the extracellular pH, it has been suggested that they are involved in the central chemosensory mechanism. In human embryonic kidney HEK293 cells transfected with P2X1, P2X3 or P2X4 receptor subunits, the currents evoked by ATP were reduced by acidification of the extracellular environment (Stoop et al. 1997). On the other hand, in HEK293 cells and in Xenopus oocytes transfected with the P2X2 receptor subunit, ATP-evoked currents were potentiated by lowering the external pH (King et al. 1996; Stoop et al. 1997; Wildman et al. 1997). Although the sensitivity of virtually all subtypes of P2X receptors to ATP is influenced by extracellular [H+], P2X2 homomeric receptors are unique in terms of their high sensitivity to the external pH within the physiological range (King et al. 1997; Wildman et al. 1997). Mild acidification (a decrease in pH from 7.45 to 7.10) increases the amplitude of submaximal inward currents evoked by ATP at recombinant P2X2 receptors by two- to threefold (Wildman et al. 1997). As ATP-evoked currents at functional heteromeric P2X2/6, P2X1/2 and P2X2/3 receptors in expression systems are also increased by acidification (Stoop et al. 1997; King et al. 2000; Brown et al. 2002), it appears that the P2X2 receptor subunit confers the sensitivity to [H+] changes onto the heteromultimeric channels.

The pH sensitivity of responses evoked by ATP at P2X receptors supports the hypothesis that purinergic signalling may play an important role in the mechanisms underlying the chemosensitivity of VLM neurones to changes in extracellular [H+] (Spyer & Thomas, 2000). If the [H+] sensitivity of P2X receptors underlies the mechanism of chemosensitivity of VLM neurones, tonic release of ATP would be required for this mechanism to operate. Indeed, results obtained in this laboratory indicate that this may be the case, as P2 receptor blockade reduces the baseline firing of VLM respiratory neurones (Thomas & Spyer, 2000).

The high sensitivity of the P2X2 receptor subtype to changes in pH suggests that the P2X receptors responsible for central CO2/pH sensitivity are likely to contain the P2X2 receptor subunit and, therefore, VLM respiratory neurones are likely to express it. Indeed, the P2X2 receptor subunit is expressed in the VLM as well as in the other areas of the brainstem known to contain chemosensitive neurones, including the pontine locus coeruleus, the nucleus tractus solitarii and the raphe nuclei (Kanjhan et al. 1999; Yao et al. 2000; Thomas et al. 2001). However, the extent of P2X receptor distribution among the VLM respiratory neurones has not yet been investigated.

The main objective of this study was to determine whether P2X2 receptor subunit immunoreactivity (P2X2 R-IR) is present in the rostral VLM respiratory neurones. We also checked whether VLM respiratory neurones express the P2X1 receptor subunit in order to characterise further the profile of P2X receptor subunits on individual VLM respiratory neurones and to compare the proportion of P2X1-expressing neurones with those expressing P2X2. In addition, the effect of ATP on the resting discharge of the VLM respiratory neurones was studied and the proportion of inspiratory and expiratory neurones that are excited by ionophoretic application of ATP was determined and compared to the proportion of these neurones that express the P2X2 receptor subunit.

METHODS

Surgical procedure

All experiments were performed on male Sprague-Dawley rats (300-340 g) and carried out in accordance with the UK Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act, 1986. The rats were anaesthetised with pentobarbitone sodium (Sagatal, May and Baker, UK; 60 mg kg−1, I.P.). Anaesthesia was maintained with supplemental doses of pentobarbitone sodium injected intravenously as required (10 mg kg−1 h−1). Adequate anaesthesia was ensured by maintaining stable levels of arterial blood pressure (ABP) and heart and central respiratory rate, and monitored by the absence of a withdrawal response to a paw pinch. The femoral artery and vein were cannulated for measurement of ABP and administration of anaesthetic, respectively. The trachea was cannulated and the animal was ventilated with O2-enriched air using a positive-pressure ventilator (Harvard rodent ventilator, model 683) with a tidal volume of 1.5-2.0 ml and a ventilator frequency similar to that of spontaneous frequency in rats. The animal was then injected with the neuromuscular blocker gallamine triethiodide (Flaxedil, 10 mg kg−1, I.V.; then 1-2 mg kg−1 h−1, I.V.) and was placed in a stereotaxic frame. An occipital craniotomy was performed and the cerebellum was partially removed to expose the dorsal surface of the brainstem. Activity of the phrenic nerve was recorded as an indicator of central respiratory drive. The signal was amplified (× 20 000), filtered (500-1500 Hz) and rectified and smoothed (τ = 100 ms). PO2 and PCO2 as well as pH of the arterial blood were measured regularly. End-tidal levels of CO2 were monitored on-line using a fast-response CO2 analyser (Analytical Development, Herts, UK) and kept at 4-5 % by altering tidal volume and respiratory frequency appropriately. The body temperature was maintained with a servo-controlled heating pad at 37.0 ± 0.2 °C.

Recording and juxtacellular labelling of VLM respiratory neurones

Single-unit activities of respiratory neurones, located in the area of rostral VLM (stereotaxic co-ordinates: 2.0-2.5 mm rostral to the calamus scriptorius, 1.5-2.0 mm lateral to midline and 2.3-3.0 mm ventral from the dorsal surface of the medulla oblongata; Paxinos & Watson, 1998) were recorded using a glass microelectrode (tip diameter 1-2 μm, resistance 15-35 mΩ). The electrode was filled with 1.5 % Neurobiotin (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) in 0.5 M NaCl. Recordings were made using an intracellular amplifier (Axoclamp-2B; Axon Instruments) in bridge mode. The recorded signal was further amplified (× 200) by an AC/DC amplifier (Neurolog System; Digitimer, UK) and filtered (0.5-1.5 kHz). Records were processed using Power 1401 interface and Spike 2 software (Cambridge Electronic Design, Cambridge, UK).

Recorded respiratory neurones were classified according to the timing of their discharge pattern in relation to that of the phrenic nerve (Schwarzacher et al. 1991) and by using certain criteria to exclude pump cells (described in Results), and were subjected to the juxtacellular labelling procedure (as described in detail by Pinault, 1996). Briefly, once a steady firing rate of the neurone had been established, positive current pulses (200 ms, 50 % duty cycle, duration up to 15 min) were delivered at sufficient amplitude (3-10 nA) to entrain the cell to discharge predominantly during these positive pulses. No changes in phrenic nerve activity were observed during the juxtacellular labelling (regardless of the current intensity) of individual respiratory neurones. The labelling was performed under continuous electrophysiological control to make sure that only one cell was entrained and filled with Neurobiotin, and in the majority of preparations we made only a single attempt to label a respiratory neurone on each side of the brain. After a period of at least 2 h after the last neurone was labelled, the animal was then deeply anaesthetised with pentobarbitone sodium (supplemental dose 20 mg kg−1, I.V.) and perfused transcardially with 400 ml of heparinised saline followed by 400 ml of 4 % paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). Brains were removed and post-fixed in the same fixative for 12-24 h at 4 °C.

Histology

Coronal sections (50 μm) of the medulla oblongata were cut on a vibrating microtome (Leica, VT1000M) and collected into phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.2). To identify juxtacellularly labelled neurones (i.e. those containing Neurobiotin), sections were incubated for 2 h in Fluorescein Avidin DCS (Vector Laboratories) diluted 1:2000 in PBS/0.1 % Triton X-100. Sections that contained labelled cells were then processed to detect P2X2 R-IR or P2X1 R-IR. Free-floating sections were incubated for 15 min in a pre-block solution (10 % normal goat serum and 0.1 % Triton X-100 in PBS) followed by 3 × 5 min washes in PBS. Sections were then incubated for 12 h at 4 °C in antibodies against either an extracellular portion of the P2X2 receptor subunit (a generous gift from Dr J. A. Barden, University of Sydney, Australia) or residues 382-399 of the intracellular C terminus of the P2X1 receptor subunit (Alomone Labs, Jerusalem, Israel). Production and characterisation of the rabbit polyclonal antibodies against the extracellular domain of the P2X2 receptor have been described in detail elsewhere (Hansen et al. 1999; Yao et al. 2000). Both antibodies were raised in rabbit and diluted 1:1000 in PBS/0.1 % Triton X-100.

Following 3 × 10 min washes in PBS, sections were incubated for 1-2 h in goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to Cy3 (1:1000 dilution; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA, USA). Sections were then washed for 3 × 10 min in PBS, air dried onto glass slides, mounted under a coverslip using VectaMount (Vector Labs) and viewed with the aid of a Nikon E600 fluorescence microscope using the appropriate filter sets. Images were captured using an AcQuis image capture system (Synoptics) and processed using Corel PhotoPaint software.

Combined immunofluorescence and peroxidase visualisation of neurones labelled juxtacellularly

We applied a method that enabled co-localisation studies using immunofluorescence with a more sensitive and permanent visualisation of labelled neurones using peroxidase reaction product. Sections were removed from the slides and incubated in biotinylated anti-avidin D antibody (Vector Laboratories) diluted 1:20 000 in PBS for 12 h, followed by 2 h in Vectastain Elite ABC reagent (Vector Laboratories) solution to ensure the recovery of the recorded cell's morphology (Hughes et al. 2000). Sections were washed in Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.4, and incubated in diaminobenzidine solution (5 mg in 10 ml in Tris-HCl buffer with 0.01 % H2O2) for 20-40 min. Sections were then air-dried onto glass slides, dehydrated in a series of ethanols, cleared in xylene and mounted under a coverslip using DPX, prior to microscopic examination. It has been found that the juxtacellular labelling procedure is sufficiently sensitive to allow immunohistochemical detection of the antigen of interest combined with description of the morphology of the medullary respiratory neurones.

Studies of the effects of ATP on the activity of VLM respiratory neurones

Discharges of respiratory neurones located in the area of rostral VLM (stereotaxic co-ordinates are given above) were recorded in a separate set of experiments. Extracellular single-unit recordings and ionophoretic application of drugs were made using five-barrelled microelectrodes (tip diameter 1-3 μm, resistance 5-15 mΩ). The recorded signal was amplified (× 10 000) and filtered (0.5-1.5 kHz). The recording barrel of the microelectrode contained NaCl (4 M). The other barrels of the microelectrode contained L-glutamate (0.1 M, pH 8.0) or saline (pH 8.0), ATP (0.2 M, pH 8.0), the P2 receptor blocker suramin (0.02 M, pH 8.0) and Pontamine Sky Blue dye (2 % in 0.2 M sodium acetate). The concentrations of ATP and suramin were chosen based on the results of the previous studies in which the effects of these drugs on the activity of rostral VLM neurones were investigated (Ralevic et al. 1999; Thomas & Spyer, 2000). L-Glutamic acid, NaCl and ATP were dissolved in distilled water; suramin was dissolved in saline. All drugs were from Sigma (Poole, UK).

Respiratory neurones were classified as described below (see Results). Once a steady firing rate of the neurone had been established, drugs were applied ionophoretically (Neurophore, Medical Systems, NY, USA). ATP was applied with currents of 20, 40, 60, 80 and 120 nA for 40 s. The effect of suramin (80 nA) on ATP-induced changes in discharge of VLM respiratory neurones was also determined. No changes in phrenic nerve activity were observed during ionophoretic application of ATP or suramin. Recording sites were marked by the ionophoretic deposition of Pontamine Sky Blue dye (500 nA; 10 min). At the end of the experiment, the animal was deeply anaesthetised with pentobarbitone sodium (supplemental dose 20 mg kg−1, I.V.) and was perfused transcardially with 100 ml of heparinised saline followed by 200 ml of 4 % paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). Brains were removed, post-fixed, sectioned serially (100 μm) and counterstained with Neutral Red. Recording sites were visualised with the aid of a light microscope and mapped using a stereotaxic atlas (Paxinos & Watson, 1998).

Recordings were processed and analysed using Spike 2 software (Cambridge Electronic Design). Single-unit activity is expressed as raw data or rate histograms after discrimination of activity with a window discriminator. Drugs were considered to induce significant changes if the ongoing activity of the neurone altered during the period of ionophoretic application by ≥20 % from averaged baseline level. Baseline firing was assessed by averaging the firing rate during the active phase of the neurone over 10-20 respiratory cycles prior to the application of drugs.

RESULTS

Identification and labelling of respiratory neurones

Neurones with respiratory-related discharge were classified according to the timing of their discharge pattern in relation to that of the phrenic nerve (Schwarzacher et al. 1991). Expiratory neurones had an onset in their discharge after the post-inspiratory phase of the phrenic neurogram, and increasing activity during the expiratory phase. Inspiratory neurones exhibited a steady increase in firing rate during the inspiratory phase of phrenic nerve activity. Pre-inspiratory neurones showed discharge starting more than 20 ms before the burst of the phrenic nerve (Guyenet & Wang, 2001), then increased firing steadily during inspiration. Post-inspiratory neurones discharged with a rapid onset immediately at the end of the inspiratory phase and then showed a decrement in firing during the post-inspiratory phase. Respiratory neurones were further characterised as follows to exclude pump cells from the sample (i.e. those receiving input from the lung stretch receptors; Guyenet & Wang, 2001). Firstly, the ventilator was briefly interrupted to verify whether in these conditions the neurone continued to fire in synchrony with the phrenic nerve (Fig. 1A). Second, the ventilator frequency and/or tidal volume were increased to cause complete cessation of phrenic nerve activity to test whether the respiratory neurone could be silenced by hyperventilation (Fig. 1B). In the area of rostral VLM where recordings were made, expiratory neurones and neurones with inspiratory-related discharge were the predominant types of active neurones.

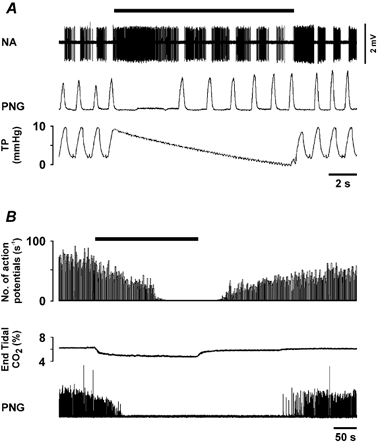

Figure 1. Identification and characterisation of the respiratory neurones in the VLM.

A, raw data illustrating the response of a VLM expiratory neurone to brief interruption of the ventilator. B, time-condensed records of the firing rate of another VLM expiratory neurone, illustrating a response to hyperventilation that results in a decrease in the end-tidal level of CO2 (bin size = 1 s). The black horizontal bars indicate periods of the ventilator interruption (A) and the duration of the hyperventilation (B). NA, neuronal activity; PNG, phrenic neurogram (arbitrary units); TP, tracheal pressure.

Seventy-two respiratory neurones were subjected to juxtacellular labelling. All neurones were successfully entrained by current pulses, with the duration of entrainment ranging from 10 s to 15 min. Only those neurones that were entrained continuously for more than 2 min were successfully recovered histologically (n = 40, Figs 2, 3, 5 and 6). It was found that longer periods of entrainment (> 3 min) are required for Neurobiotin to satisfactorily fill the processes of the recorded neurones. In 11 out of 12 respiratory neurones (both P2X2 R-IR and non-P2X2 R-IR) that were visualised with peroxidase product, these processes were traced for several hundred microns (Fig. 6). Of these 40 histologically recovered VLM respiratory neurones, 22 (55 %) were expiratory, nine (22.5 %) were pre-inspiratory, seven (17.5 %) were inspiratory and only two (5 %) were post-inspiratory. Twenty-five and 15 of these neurones were processed to determine whether they contained P2X2 R-IR or P2X1 R-IR, respectively. In addition, four neurones that were found to be P2X2-negative were processed further to determine whether they expressed the P2X1 receptor subunit.

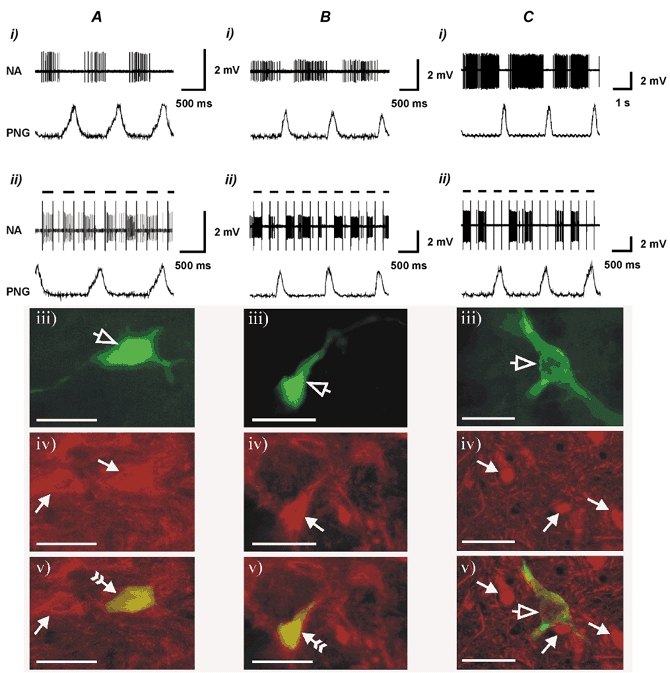

Figure 2. P2X2 R-IR expiratory neurones in the VLM.

Shown are the resting discharge pattern (i), the effect of juxtacellular stimulation (ii), histological recovery (visualisation of Neurobiotin-labelled neurones using Fluorescein Avidin DCS) (iii) and P2X2 receptor subunit immunohistochemistry showing P2X2-immunoreactive (A and B) and non-P2X2-immunoreactive (C) VLM expiratory neurones (iv) and combined images of Neurobiotin visualisation and P2X2 R-IR (v). Open arrowheads point to the labelled neurones. Filled arrowheads point to the neurones that are P2X2 R-IR. Filled arrowheads with a tail point to the Neurobiotin-labelled neurones that are P2X2 R-IR. Note: the neurone illustrated in B is the same neurone that is shown in Fig. 6C. Black horizontal bars indicate positive current pulses (4−8 nA) during juxtacellular stimulation. Scale bar in photomicrographs = 40 μm.

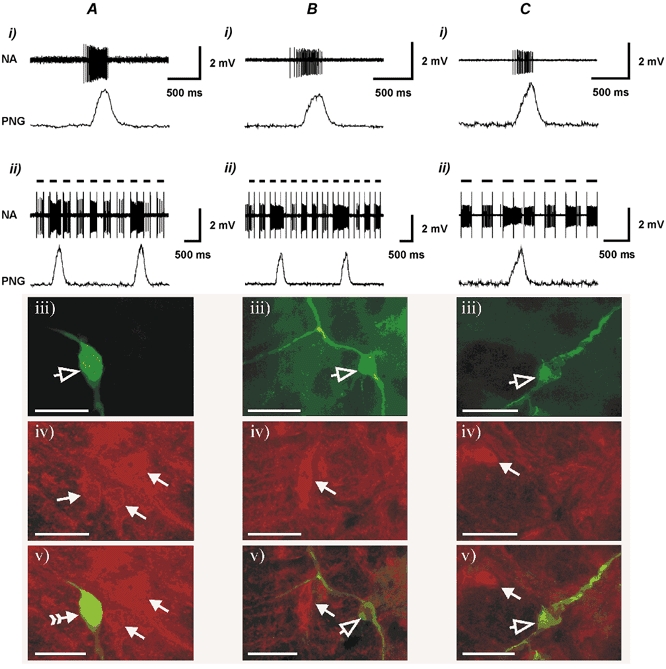

Figure 3. P2X2 R-IR neurones with inspiratory-related discharge in the VLM.

Shown are the resting discharge pattern (i), the effect of juxtacellular stimulation (ii), histological recovery (visualisation of Neurobiotin-labelled neurones using Fluorescein Avidin DCS) (iii) and P2X2 receptor subunit immunohistochemistry of P2X2 R-IR (A) and non-P2X2 R-IR pre-inspiratory (B) as well as non-P2X2 R-IR inspiratory (C) VLM neurones (iv) and combined images of Neurobiotin visualisation and P2X2 R-IR (v). Open arrowheads point to the Neurobiotin-labelled neurones. Filled arrowheads point to P2X2 R-IR neurones. The filled arrowhead with the tail points to the Neurobiotin-labelled neurone that is also P2X2 R-IR. Note: the neurone illustrated in A is the same neurone that is shown in Fig. 6A. Black horizontal bars indicate positive current pulses (4−8 nA) during juxtacellular stimulation. Scale bar = 40 μm.

Figure 5. P2X1 receptor subunit immunoreactivity.

Shown are the resting discharge pattern (i), the effect of juxtacellular stimulation (ii) histological recovery (visualisation of Neurobiotin-labelled neurones using Fluorescein Avidin DCS) (iii) and P2X1 receptor subunit immunohistochemistry of non-P2X1 R-IR expiratory (A) and inspiratory (B) neurones in the ventrolateral medulla (iv) and combined image of Neurobiotin visualisation and P2X1 R-IR (v). Open arrowheads point to the Neurobiotin-labelled neurones. Black horizontal bars indicate positive current pulses (4−8 nA) during juxtacellular stimulation. Scale bar = 40 μm.

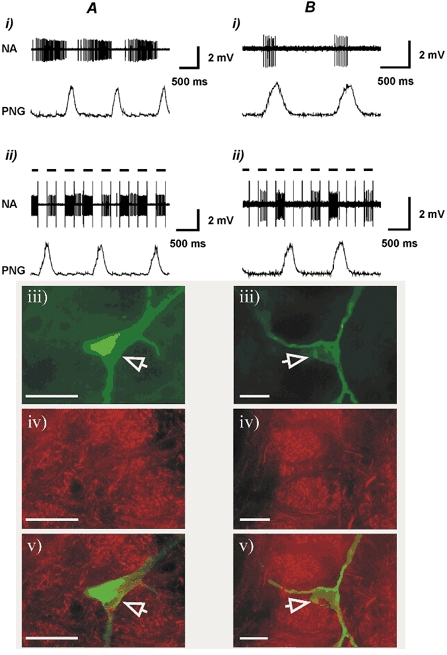

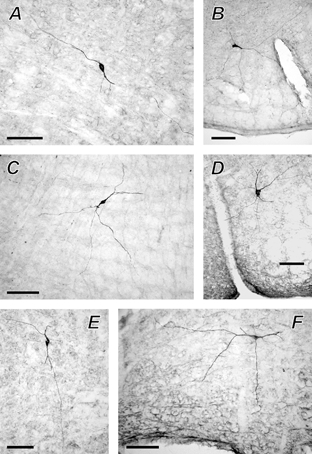

Figure 6. Morphology of the P2X2 R-IR neurones in the VLM.

Photomicrographs of the VLM respiratory neurones that were recovered after juxtacellular labelling, processed for P2X2 receptor subunit immunohistochemistry and visualised with a permanent peroxidase reaction product. A, P2X2 R-IR pre-inspiratory neurone; B−E, P2X2 R-IR expiratory neurones; F, non-P2X2 R-IR expiratory neurone. Scale bar = 100 μm.

P2X2 R-IR in VLM respiratory neurones

The resting discharge pattern, the effect of the juxtacellular stimulation and both histological recovery and P2X2 receptor subunit immunohistochemistry of VLM expiratory, pre-inspiratory and inspiratory neurones are illustrated in Fig. 2 and Fig. 3. Out of 12 labelled expiratory neurones, six (50 %) contained P2X2 R-IR (Fig. 2A and B). Two out of seven (29 %) labelled pre-inspiratory neurones contained P2X2 R-IR (Fig. 3A) and the rest were P2X2-negative (Fig. 3B). None of the labelled VLM inspiratory neurones (n = 4) contained detectable P2X2 R-IR (Fig. 3C). Combining the two populations of neurones reveals that ≈20 % of VLM neurones with inspiratory-related discharge expressed the P2X2 receptor subunit (two out of 11). Those respiratory neurones that were negative for P2X2 R-IR were often located adjacent to P2X2 R-IR neurones, indicating the effectiveness of the immunofluorescence procedure (Fig. 2C and Fig. 3B and C). In addition, one out of only two labelled post-inspiratory neurones was P2X2 R-IR (data not shown).

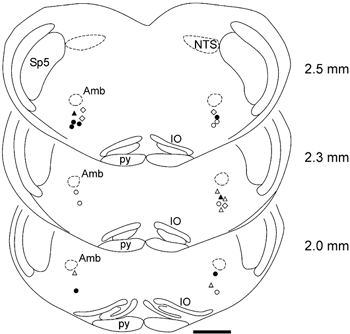

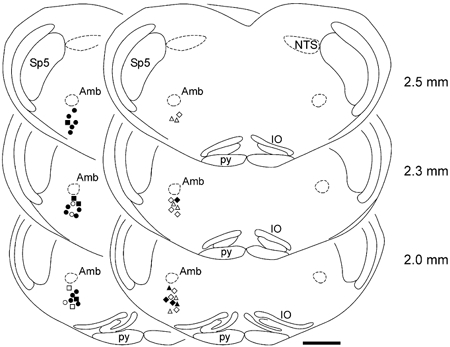

In Fig. 4, the location of the 23 labelled respiratory neurones processed for detection of P2X2 R-IR is shown. All neurones were found to be located in the anatomical region of rostral VLM corresponding to Bötzinger and pre-Bötzinger areas, according to classifications by Kanjhan et al. (1995), Stornetta et al. (2003) and to the atlas by Paxinos & Watson (1998). Four of the most rostral P2X2 R-IR expiratory neurones and both P2X2 R-IR pre-inspiratory neurones were located within the boundaries of the Bötzinger complex (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Location of the 23 Neurobiotin-labelled respiratory neurones that were processed for detection of P2X2 R-IR.

Filled and open circles indicate locations of the P2X2 R-IR and non-P2X2 R-IR expiratory neurones, respectively. Filled and open triangles indicate locations of the P2X2 R-IR and non-P2X2 R-IR pre-inspiratory neurones, respectively. Open diamonds indicate locations of the non-P2X2 R-IR inspiratory neurones. Numbers indicate distance from the calamus scriptorius. Amb, nucleus ambiguus; IO, inferior olive; NTS, nucleus of the solitary tract; py, pyramidal tract; Sp5, spinal trigeminal nucleus. Anatomical structures are labelled according to the classification of Paxinos & Watson (1998). Scale bar = 1 mm.

P2X1 receptor subunit immunoreactivity

Only a few scattered neurones containing P2X1 R-IR were found along the entire rostrocaudal axis of the VLM. However, no labelled VLM expiratory (n = 10), pre-inspiratory (n = 4) or inspiratory (n = 5) neurones were detectably immunoreactive for the P2X1 receptor subunit (Fig. 5).

Peroxidase recovery of neurones following P2X2 immunohistochemistry

Following the detection of P2X2 R-IR, the fluorescein-labelled cells were visualised using a peroxidase reaction to allow permanent mounting and better visualisation of fine dendritic processes, which are unclear under fluorescence microscopy (n = 12). The morphology of six neurones (five of these were P2X2 R-IR) is illustrated in Fig. 6. The neurone shown in Fig. 6A is the same P2X2 R-IR pre-inspiratory neurone as shown in Fig. 3A, and the neurone shown in Fig. 6C is the same P2X2 R-IR expiratory neurone as shown in Fig. 2B.

Effect of ATP on the electrical activity of VLM respiratory neurones

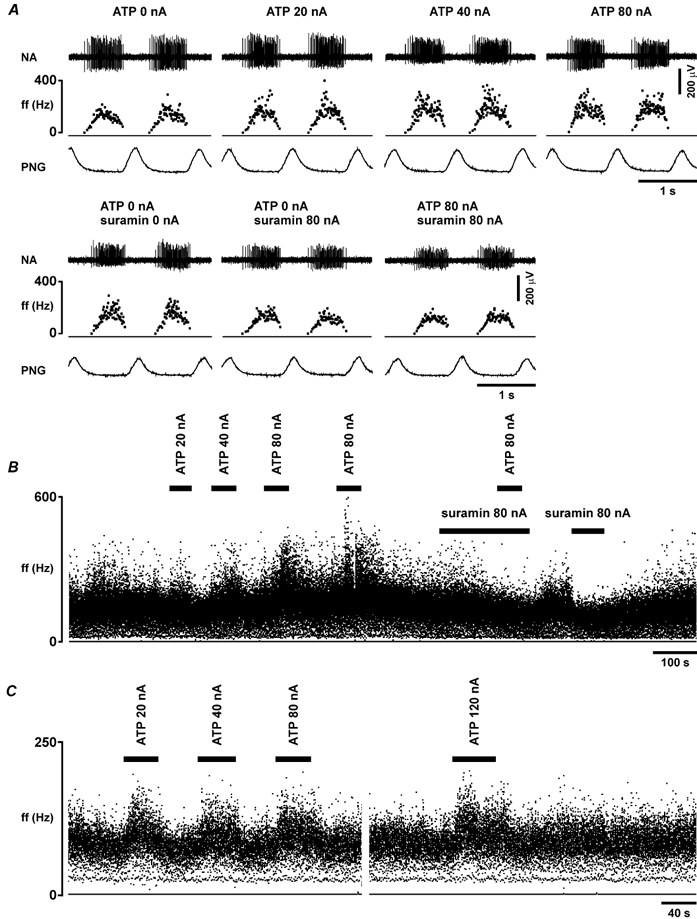

Extracellular recordings were made from a total of 40 VLM respiratory neurones. Ionophoretic application of the vehicle (saline, pH 8.0; 80 nA) had no effect on the discharge of any neurone tested (n = 5). Application of ATP (0.2 M; 20-80 nA; for 40 s) evoked a current-dependent increase in the resting firing in 13 out of 16 (≈80 %) VLM expiratory neurones (Fig. 7; Table 1). This increase in the discharge frequency in response to ATP was observed only during the active phase of the neurone; firing was not induced by ATP during the normally silent phase of the neurone, and changes in the duration of firing were less than 10 % (Fig. 7A). This excitatory effect of ATP on expiratory neurones was blocked by the ionophoretic application of the P2 receptor antagonist suramin (0.02 M; 80 nA), which also reduced the baseline firing in some (three out of six tested; 23 ± 2 % reduction) of these neurones (Fig. 7). In addition, four out of six (66 %) recorded post-inspiratory neurones were also excited by ionophoretic application of ATP (Fig. 7C; Table 1).

Figure 7. Effect of ATP on the electrical activity of the expiratory and post-inspiratory neurones in the VLM.

A, raw data illustrating the response of the expiratory neurone to ionophoretic application of ATP (0.2 m), applied using the currents shown, in the absence and presence of the P2 receptor blocker suramin (0.02 m), which was applied ionophoretically. B, time-condensed records of the firing rate of the same neurone, illustrating responses to ionophoretic application of ATP, applied using the currents shown, in the absence and presence of suramin. C, time-condensed records of the firing rate of the post-inspiratory neurone, illustrating responses to the ionophoretic application of ATP (0.2 m), applied using the currents shown. Black horizontal bars indicate timing of ATP or suramin application. ff, instantaneous firing frequency.

Table 1.

Effect of ATP on the firing rate of VLM respiratory neurones

| ATP(0.2 m) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 20 nA | 40 nA | 80 nA | |

| Expiratory neurones | 26 ± 4%(11) | 41 ± 8%(13) | 49 ± 11%(13) |

| Post-inspiratory neurones | 32 ± 1%(3) | 36 ± 16%(4) | 63 ± 28%(4) |

| Neurones with inspiratory-related discharge (inspiratory and pre-inspiratory) | 35 ± 9%(5) | 36 ± 5%(5) | 68 ± 2%(4) |

Data are presented as means ± s.e.m. of the change from baseline firing rate in neurones that displayed ≥ 20% increase in the ongoing activity during ionophorectic application of ATP. Numbers in parentheses indicate sample sizes.

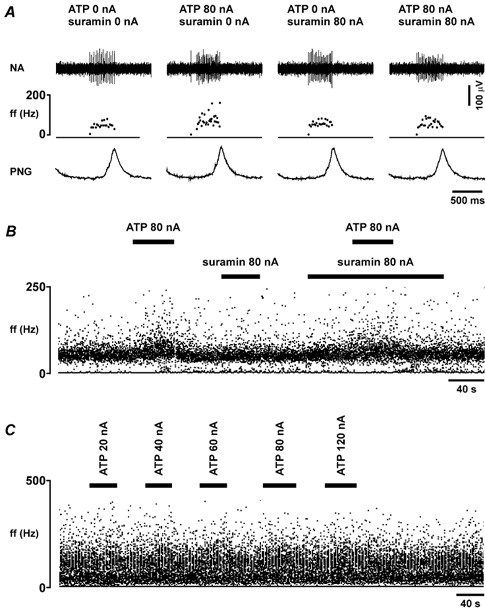

ATP (0.2 M; 20-120 nA; for 40 s) evoked a current-dependent increase in discharge in three out of 10 (30 %) VLM inspiratory neurones and in two out of eight (25 %) recorded VLM pre-inspiratory neurones (Fig. 8A and B; Table 1); the rest were unaffected by ATP (Fig. 8C). Hence, if these two populations of neurones are combined, ATP was able to induce an increase in activity of ≈30 % of VLM neurones with inspiratory-related discharge (five out of 18). As with expiratory neurones, an increase in the discharge frequency in response to ATP was observed exclusively during the active phase of the neurone, while no firing was induced by ATP during the silent phase of the neurone, and changes in the duration of firing were less than 10 % (Fig. 8A). The effect of ATP on the firing of VLM neurones with inspiratory-related discharge was abolished by the P2 receptor blocker suramin (0.02 M; 80 nA; Fig. 8A and B).

Figure 8. Effect of ATP on the electrical activity of the neurones with inspiratory-related discharge in the VLM.

A, raw data illustrating the response of the pre-inspiratory neurone to ionophoretic application of ATP (0.2 m), applied using the current shown, in the absence and presence of the P2 receptor blocker suramin (0.02 m), which was applied ionophoretically. B, time-condensed records of the firing rate of the same neurone, illustrating responses to ionophoretic application of ATP in the absence and presence of suramin. C, time-condensed records of the firing rate of the inspiratory neurone, illustrating the absence of a significant response to ionophoretic application of ATP (0.2 M), which was applied using the currents shown. Black horizontal bars indicate timing of ATP or suramin application.

In Fig. 9, the location of all 40 recorded respiratory neurones tested in terms of their responsiveness to the ionophoretic application of ATP is shown. All neurones were found to be located in the anatomical region of the rostral VLM corresponding to Bötzinger and pre-Bötzinger areas, according to classifications by Kanjhan et al. (1995), Stornetta et al. (2003) and to the atlas by Paxinos & Watson (1998). Expiratory and post-inspiratory neurones excited by ATP were found in the most rostral as well as in the most caudal recording sites. Two pre-inspiratory and two inspiratory neurones that increased their activity during ionophoretic application of ATP were located in the most caudal recording sites, most likely within the pre-Bötzinger area (Fig. 9).

Figure 9. Location of the 40 respiratory neurones tested in terms of their responsiveness to the ionophoretic application of ATP.

The location of the recording sites was identified by ionophoretic deposition of Pontamine Sky Blue Dye. Filled and open circles indicate locations of the expiratory neurones that were excited or were not affected by ionophoretic application of ATP, respectively. Filled and open squares indicate locations of the post-inspiratory neurones that were excited or were not affected by ionophoretic application of ATP, respectively. Filled and open triangles indicate locations of the pre-inspiratory neurones that were excited or were not affected by ionophoretic application of ATP, respectively. Filled and open diamonds indicate locations of the inspiratory neurones that were excited or were not affected by ionophoretic application of ATP, respectively. Numbers indicate distance from the calamus scriptorius. Anatomical structures are labelled according to the classification of Paxinos & Watson (1998). Scale bar = 1 mm.

DISCUSSION

The main objective of the present study was to determine whether respiratory neurones in the rostral VLM express the P2X2 receptor subunit of the ATP-gated ion channel. This was triggered by previous pharmacological evidence indicating that ATP acting via P2X receptors is involved in central respiratory control (Thomas et al. 2001) and may be responsible for mediating changes in the activity of VLM respiratory neurones during hypercapnia (Thomas et al. 1999; Spyer & Thomas, 2000; Thomas & Spyer, 2000).

In the area of rostral VLM, a significant proportion of neurones that display rhythmic respiratory-related activity were found to express P2X2, but not P2X1 receptor subunits. Even more VLM respiratory neurones were found to increase their discharge in response to microionophoretic application of ATP. Interestingly, this increase in the discharge frequency in response to ATP was observed only during the active phase of the respiratory neurone. Firing was not induced by ATP during the normally silent phase of the neurone, indicating that action of ATP applied ionophoretically at a concentration of 0.2 M using currents up to 120 nA is not sufficient to overcome synaptic (reciprocal) inhibition of these VLM respiratory neurones.

The increase in the discharge during the active phases of the neurones was in most cases sustained during the whole period of ATP application (up to 40 s), which is consistent with it being mediated by slowly desensitising P2 receptors such as those containing the P2X2 receptor subunit. The failure of ATP to induce a sustained increase in firing of some respiratory neurones during the whole period of application could be considered to be due to the expression of rapidly desensitising P2X receptors. P2X1 and P2X3 receptors are known to desensitise rapidly (Ralevich & Burnstock, 1998; North, 2002). In the present study, no labelled VLM neurones (n = 19) with respiratory-related discharge were found to be detectably immunoreactive for the P2X1 receptor subunit. In addition, Thomas et al. (2001) failed to detect any P2X3 R-IR in the rostral ventrolateral medulla, while in the study of Yao et al. (2000) some P2X3-immunoreactive neurones were found in this part of the brainstem, although this latter study did not relate immunoreactivity specifically to respiratory neurones. Thus, given the contradictory evidence, it is unknown whether or not VLM respiratory neurones express P2X3 receptors and whether their rapid desensitisation is responsible for the failure of ATP to induce a sustained increase in firing of these neurones.

P2X2 receptor subunit of the ATP-gated ion channel in medullary mechanisms of respiratory control

This study has indicated that extracellular ATP may be an important modulator of the activity of VLM respiratory neurones. What is the functional role of the P2X receptors that contain P2X2 receptor subunit in regulation of the activity of VLM respiratory neurones? It is clear that studies involving microionophoretic application or microinjection of agonists, such as ATP, are not sufficient to determine this role. However, experiments in which P2X receptors in this area of the brainstem are blocked by specific antagonists applied either by microinjection or ionophoretically, and the effect of this treatment on central respiratory drive and (or) activity of VLM expiratory neurones is monitored may provide useful information. When the P2 receptor antagonist suramin was given unilaterally into the VLM by microinjection, no changes in respiration were observed (Thomas et al. 2001). However, when suramin was applied bilaterally into the VLM, resting phrenic nerve discharge was markedly reduced (Thomas et al. 1999), suggesting that the VLM respiratory network ‘as a whole’ is under tonic excitatory influence mediated by P2 receptors. This is supported by our data showing that microionophoretic application of either suramin or PPADS reduces the baseline firing of the majority of pre-inspiratory and inspiratory neurones (Thomas & Spyer, 2000) as well as of some expiratory neurones in this area of the medulla (present study). Since the selectivity and specificity of the commonly used P2 receptor antagonists suramin and PPADS are uncertain, these data must be interpreted cautiously. In this context, suramin has been reported to act on other receptors such as those for glutamate and GABA (Nakazava et al. 1995). However, earlier studies from this laboratory demonstrated that neither suramin nor PPADS affect the excitatory effect of glutamate on any VLM respiratory neurone recorded (Thomas & Spyer, 2000).

It is important to emphasise that our labelling and recording sites were confined to a relatively small region of the rostral VLM corresponding to the Bötzinger and pre-Bötzinger areas, which are known to contain respiratory neurones that are responsible for the generation and shaping of central respiratory output in mammals. Interestingly, it was found that both P2X2-IR pre-inspiratory neurones and four P2X2-IR expiratory neurones were located within the boundaries of the Bötzinger complex. Furthermore, the majority of expiratory neurones within the area of the Bötzinger complex increased their discharge during application of ATP. This indicates that P2X2-receptor-mediated modulation may be of a great significance in determining the activity of the expiratory neurones in the Bötzinger complex, which inhibit phrenic motor neurones and other respiratory neurones in the medulla. It is possible, however, that the populations of neurones (e.g. expiratory and pre-inspiratory) reported in this study could be comprised of heterogeneous cells in terms of their phenotype and function (although their firing pattern is similar). Nevertheless, the demonstration that a significant proportion of respiratory neurones located in the vicinity of the Bötzinger and pre-Bötzinger areas express the P2X2 receptor subunit and respond with the increase in discharge during ATP application suggests that purinergic signalling plays an important, and as yet unknown, role in generation and shaping of central respiratory output.

Taken together, these data suggest that a significant proportion of the VLM respiratory neurones are under tonic excitatory influence of ATP mediated by ionotropic P2X receptors that contain the P2X2 receptor subunit. However, the potential functional role of these P2X2 receptors that are expressed by VLM respiratory neurones and mediate tonic ATP-induced excitatory drive under basal conditions may not be related to the generation and shaping of central respiratory output, but may be responsible for the sensitivity of these neurones to changes in local [H+].

P2X2 receptor subunit of the ATP-gated ion channel and chemosensitivity of the VLM respiratory neurones

Earlier observations from this laboratory have suggested that P2X receptors are responsible for the sensitivity of the VLM respiratory neurones to changes in PCO2/[H+] (Thomas et al. 1999; Thomas & Spyer, 2000). As mentioned in the introduction, the P2X2 subunit is essential for the high sensitivity of the P2X receptors to mild [H+] changes in the extracellular environment (King et al. 1997, 2000; Wildman et al. 1997; Brown et al. 2002). Therefore, if purinergic signalling is involved in the mechanisms of central CO2/[H+] sensitivity, VLM chemosensitive neurones should express the P2X2 receptor subunit. It would also be expected that their discharge would increase on application of ATP.

However, it is likely that many neurones in the medulla oblongata are sensitive to changes in extracellular [H+]. As yet there are no firm criteria to distinguish between chemosensitive neurones that provide input to the respiratory network (respiratory chemosensitive) from those that do not (non-respiratory chemosensitive). As suggested by Ballantyne & Scheid (2000), ‘one approach to looking for connections between chemosensitive neurones and the neurones controlling ventilation is to use the respiratory rhythm itself as an indication of connectivity, and to ask whether neurones showing this rhythm are also chemosensitive’. This is exactly the approach we have used in determining whether or not neurones showing respiratory rhythm express the P2X2 receptor subunit and respond with an increase in their discharge to ionophoretic application of ATP.

The results of the present study show that a significant proportion of the VLM respiratory neurones express the P2X2 receptor subunit and increase their firing in response to ATP. This suggests that P2X2 receptors do indeed underlie CO2-induced excitation of at least the neurones that express these receptors. However, the unexpected finding of the present study is that in the VLM only approximately 20 % of neurones that displayed rhythmic inspiratory-related activity contained P2X2 R-IR, indicating that the proportion of VLM pre-inspiratory and inspiratory neurones that express P2X2 receptor subunit is smaller than the proportion of these cells that are excited during hypercapnia. An earlier study showed that increasing inspired CO2 excited 85 % of inspiratory and 66 % of pre-inspiratory neurones in the area of rostral VLM (Thomas & Spyer, 2000). In all cases, excitation of these neurones during hypercapnia was reduced or abolished by microionophoretic application of suramin or PPADS (Thomas & Spyer, 2000). Considering these data together, we conclude that P2X receptors that contain P2X2 subunits are unlikely to be the sole factor responsible for CO2-induced excitation of the VLM pre-inspiratory and inspiratory neurones.

It is possible that P2X receptors that contain P2X2 receptor subunits are located presynaptically or on ‘non-respiratory’ VLM neurones that are activated during hypercapnia and provide excitatory drive to the pre-inspiratory and inspiratory neurones in this area of the brainstem. If this hypothesis is correct, then VLM neurones with inspiratory-related discharge may not necessarily express P2X2 receptor proteins to exhibit chemosensitivity. Sensitivity to changes in PCO2/[H+] could be a property of other VLM neurones that may not have respiratory-related modulation of their activity. If this is the case, then the effect of P2 receptor antagonists on changes in activity of VLM pre-inspiratory and inspiratory neurones during hypercapnia could be explained by their action on the adjacent chemosensitive elements that express P2X2 receptor subunits and provide excitatory drive to the VLM neurones with inspiratory-related discharge. However, in order to operate, this mechanism requires either electrical coupling between these putative non-respiratory chemosensitive neurones and VLM inspiratory neurones (not yet documented) or intact chemical synaptic transmission. As shown by Kawai et al. (1996), the latter is not essential, since VLM inspiratory neurones demonstrate inherent chemosensitivity to changes in PCO2/[H+] that is not affected by synaptic blockade or tetrodotoxin application.

It is also possible that the sensitivity of VLM inspiratory neurones to changes in PCO2/[H+] is mediated by P2 receptors that do not contain P2X2 or P2X1 receptor subunits, perhaps by metabotropic P2Y receptors or by P2X3, P2X4 or P2X5 receptors, all of which have been identified immunohistochemically in the VLM in addition to P2X2 (Yao et al. 2000; Thomas et al. 2001). Deuchars et al. (2001) have also demonstrated that P2X7 receptors are present in presynaptic excitatory terminals in the medulla oblongata.

Taken together, the results of the present study combined with the previously published data (Thomas & Spyer, 2000) suggest that P2X receptors other than, or in addition to, P2X2 receptors, or P2Y receptors are involved in mediating hypercapnia-induced changes in the activity of VLM neurones with inspiratory-related discharge.

Conclusion

The results of the present study indicate that a significant proportion of VLM neurones that display rhythmic respiratory-related activity express P2X2 receptor subunits and increase their discharge in response to exogenously applied ATP. We suggest that these VLM respiratory neurones are under the tonic excitatory influence of ATP mediated by ionotropic P2X receptors that contain the P2X2 receptor subunit. These observations also suggest that modulation of P2X2 receptor function, such as that evoked by acidification of the extracellular environment during hypercapnia, contribute to the changes in activity of the VLM respiratory neurones that express these receptors. As a significant proportion of respiratory neurones located in the vicinity of the Bötzinger and pre-Bötzinger areas express the P2X2 receptor subunit and respond with an increase in discharge during ATP application, we suggest that purinergic signalling plays an additional, although as yet unknown, role in the generation and shaping of central respiratory output.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr J. A. Barden (University of Sydney, Australia) and Dr A. J. Lawrence (Monash University, Australia) for providing the anti-P2X2 antibody, Dr G. Jones for helpful suggestions on the procedures of the juxtacellular labelling, and the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council for financial support.

REFERENCES

- Ballantyne D, Scheid P. Mammalian brainstem chemosensitive neurones: linking them to respiration in vitro. J Physiol. 2000;525:567–577. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00567.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballantyne D, Scheid P. Central chemosensitivity of respiration: a brief overview. Respir Physiol. 2001;129:5–12. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(01)00297-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SG, Townsend-Nicholson A, Jacobson KA, Burnstock G, King BF. Heteromultimeric P2X1/2 receptors show a novel sensitivity to extracellular pH. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;300:673–680. doi: 10.1124/jpet.300.2.673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buell G, Collo G, Rassendren F. P2X receptors: an emerging channel family. Eur J Neurosci. 1996;8:2221–2228. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1996.tb00745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherniack NS. Physiological roles of central chemoreceptors. In: Speck DF, Dekin MS, Revellette WR, Frazier DT, editors. Respiratory Control – Central and Peripheral Mechanisms. University Press of Kentucky; 1993. pp. 138–146. [Google Scholar]

- Deuchars SA, Atkinson L, Brooke RE, Musa H, Milligan CJ, Batten TF, Buckley NJ, Parson SH, Deuchars J. Neuronal P2X7 receptors are targeted to presynaptic terminals in the central and peripheral nervous systems. J Neurosci. 2001;21:7143–7152. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-18-07143.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffin J, Ezure K, Lipski J. Breathing rhythm generation: focus on the rostral ventrolateral medulla. News Physiol Sci. 1995;10:133–140. [Google Scholar]

- Guyenet PG, Wang H. Pre-Bötzinger neurons with preinspiratory discharges ‘in vivo’ express NK1 receptors in the rat. J Neurophysiol. 2001;86:438–446. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.86.1.438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen MA, Dutton JL, Balcar VJ, Barden JA, Bennett MR. P2X (purinergic) receptor distributions in rat blood vessels. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1999;75:147–155. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1838(98)00189-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes DI, Bannister AP, Pawelzik H, Thomson AM. Double immunofluorescence, peroxidase labelling and ultrastructural analysis of interneurones following prolonged electrophysiological recordings in vitro. J Neurosci Methods. 2000;101:107–116. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(00)00254-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanjhan R, Housley GD, Burton LD, Christie DL, Kippenberger A, Thorne PR, Luo L, Ryan AF. Distribution of the P2X2 receptor subunit of the ATP-gated ion channels in the rat central nervous system. J Comp Neurol. 1999;407:11–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanjhan R, Lipski J, Kruszewska B, Rong W. A comparative study of pre-sympathetic and Botzinger neurons in the rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM) of the rat. Brain Res. 1995;699:19–32. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00814-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai A, Ballantyne D, Muckenhoff K, Scheid P. Chemosensitive medullary neurones in the brainstem-spinal cord preparation of the neonatal rat. J Physiol. 1996;492:277–292. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King BF, Townsend-Nicholson A, Wildman SS, Thomas T, Spyer KM, Burnstock G. Coexpression of rat P2X2 and P2X6 subunits in Xenopus oocytes. J Neurosci. 2000;20:4871–4877. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-13-04871.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King BF, Wildman SS, Ziganshina LE, Pintor J, Burnstock G. Effects of extracellular pH on agonism and antagonism at a recombinant P2X2 receptor. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;121:1445–1453. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King BF, Ziganshina LE, Pintor J, Burnstock G. Full sensitivity of P2X2 purinoceptor to ATP revealed by changing extracellular pH. Br J Pharmacol. 1996;117:1371–1373. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15293.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeschcke HH. Central chemosensitivity and the reaction theory. J Physiol. 1982;32:1–24. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1982.sp014397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrimmon DR, Ramirez JM, Alford S, Zuperku EJ. Unraveling the mechanism for respiratory rhythm generation. Bioessays. 2000;22:6–9. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(200001)22:1<6::AID-BIES3>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakazawa K, Inoue K, Ito K, Koizumi S, Inoue K. Inhibition by suramin and reactive blue 2 of GABA and glutamate receptor channels in rat hippocampal neurons. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1995;351:202–208. doi: 10.1007/BF00169334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nattie E. CO2, brainstem chemoreceptors and breathing. Prog Neurobiol. 1999;59:299–331. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(99)00008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North RA. Molecular physiology of P2X receptors. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:1013–1067. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00015.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. London: Academic Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Pinault D. A novel single-cell staining procedure performed in vivo under electrophysiological control: morpho-functional features of juxtacellularly labeled thalamic cells and other central neurons with biocytin or Neurobiotin. J Neurosci Methods. 1996;65:113–136. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(95)00144-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ralevic V, Burnstock G. Receptors for purines and pyrimidines. Pharmacol Rev. 1998;50:413–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ralevic V, Thomas T, Burnstock G, Spyer KM. Characterization of P2 receptors modulating neural activity in rat rostral ventrolateral medulla. Neuroscience. 1999;94:867–878. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00376-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter DW. Generation and maintenance of the respiratory rhythm. J Exp Biol. 1982;100:93–107. doi: 10.1242/jeb.100.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter DW, Ballanyi K, Schwarzacher S. Mechanisms of respiratory rhythm generation. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1992;2:788–793. doi: 10.1016/0959-4388(92)90135-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter DW, Spyer KM. Studying rhythmogenesis of breathing: comparison of in vivo and in vitro models. Trends Neurosci. 2001;24:464–472. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01867-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritucci NA, Chambers-Kersh L, Dean JB, Putnam RW. Intracellular pH regulation in neurons from chemosensitive and nonchemosensitive areas of the medulla. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:R1152–1163. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.275.4.R1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzacher SW, Wilhelm Z, Anders K, Richter DW. The medullary respiratory network in the rat. J Physiol. 1991;435:631–644. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spyer KM, Thomas T. Sensing arterial CO2 levels: a role for medullary P2X receptors. J Auton Nerv Syst. 2000;81:228–235. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1838(00)00118-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoop R, Surprenant A, North RA. Different sensitivities to pH of ATP-induced currents at four cloned P2X receptors. J Neurophysiol. 1997;78:1837–1840. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.78.4.1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stornetta RL, Rosin DL, Wang H, Sevigny CP, Weston MC, Guyenet PG. A group of glutamatergic interneurons expressing high levels of both neurokinin-1 receptors and somatostatin identifies the region of the pre-Bötzinger complex. J Comp Neurol. 2003;455:499–512. doi: 10.1002/cne.10504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas T, Ralevic V, Bardini M, Burnstock G, Spyer KM. Evidence for the involvement of purinergic signalling in the control of respiration. Neuroscience. 2001;107:481–490. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00363-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas T, Ralevic V, Gadd CA, Spyer KM. Central CO2 chemoreception: a mechanism involving P2 purinoceptors localized in the ventrolateral medulla of the anaesthetized rat. J Physiol. 1999;517:899–905. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.00899.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas T, Spyer KM. ATP as a mediator of mammalian central CO2 chemoreception. J Physiol. 2000;523:441–447. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00441.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wildman SS, King BF, Burnstock G. Potentiation of ATP-responses at a recombinant P2X2 receptor by neurotransmitters and related substances. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;120:221–224. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0700903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao ST, Barden JA, Finkelstein DI, Bennett MR, Lawrence AJ. Comparative study on the distribution patterns of P2X1-P2X6 receptor immunoreactivity in the brainstem of the rat and the common marmoset (Callithrix jacchus): association with catecholamine cell groups. J Comp Neurol. 2000;427:485–507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]