Abstract

While the impact of exogenous glucocorticoids on the fetal cardiovascular system has been well defined, relatively few studies have characterised the role of endogenous fetal glucocorticoids in the regulation of arterial blood pressure (BP) during late gestation. We have therefore infused metyrapone, an inhibitor of cortisol biosynthesis, into fetal sheep from 125 days gestation (when fetal cortisol concentrations are low) and from 137 days gestation (when fetal cortisol concentrations are increasing) and measured fetal plasma cortisol, 11-desoxycortisol and ACTH, fetal systolic, diastolic and mean arterial BP, heart rate, and the fetal BP responses to increasing doses of angiotensin II (AII). At 125 days gestation, there was a significant increase in fetal plasma ACTH and 11-desoxycortisol by 24 h after (+24 h) the start of the metyrapone infusion, and plasma cortisol concentrations were not different at +24 h when compared with pre-infusion values. Whilst the initial fall in circulating cortisol concentrations may have been transient, systolic, diastolic and mean arterial BP were ∼5–6 mmHg lower (P < 0.05) in metyrapone- than in vehicle-infused fetuses at 24–48 h after the start of the infusion. When metyrapone was infused from 137/138 days gestation, there was a significant decrease in plasma cortisol concentrations by +6 h, which was followed by an increase back to pre-infusion values. While cortisol concentrations decreased, there was no change in fetal mean arterial BP during the first 24 h after the start of metyrapone infusion. Mean fetal arterial BP values at 137–139 days gestation were not different in fetuses that had been infused with either vehicle or metyrapone from 125 days gestation or with metyrapone from 137–138 days gestation. At 137–139 days gestation, however, arterial BP responses to increasing doses of AII were significantly blunted in fetuses that had been infused with metyrapone from 125 days gestation, when compared with fetuses that had been infused with metyrapone from 137/138 days gestation or with vehicle from 125 days gestation. The dissociation of the gestational age increase in arterial BP and the effects of intrafetal AII on fetal arterial BP indicates that increase in fetal BP with gestational age is not entirely a result of an increased vascular responsiveness to endogenous AII. Furthermore there may be a critical window during late gestation when the actions of cortisol contribute to the development of vascular responsiveness to AII.

A range of studies have demonstrated that administration of either synthetic or native glucocorticoids in the sheep fetus during late gestation results in an increase in fetal arterial blood pressure (BP; Tangalakis et al. 1992; Derks et al. 1997; Forhead et al. 2000; Fletcher et al. 2002), an increase in the vascular resistance of the fetal femoral arterial circulation (Derks et al. 1997; Fletcher et al. 2002) and changes in the responsiveness of isolated fetal femoral arteries to excess potassium, acetylcholine and bradykinin (Anwar et al. 1999). Fetal cortisol infusion also results in an increase in the vascular sensitivity to exogenous AII (Tangalakis et al. 1992) and a greater hypotensive response to administration of an AII type 1 (AT1)- specific receptor antagonist (Forhead et al. 2000). While the impact of exogenous glucocorticoids on the fetal cardiovascular system has been well defined, there are relatively few studies that have characterised the role of endogenous fetal glucocorticoids in the regulation of arterial BP during late gestation. In the sheep, the prepartum increase in fetal plasma concentrations of cortisol occurs in parallel with an increase in fetal arterial BP (Boddy et al. 1974; Tangalakis et al. 1992; Daniel et al. 1996; Fowden et al. 1998; Unno et al. 1999) and there is a correlation between the magnitude of the fetal hypotensive response to an AT1 receptor antagonist and circulating cortisol concentrations in fetuses during late gestation (Forhead et al. 2000). Recently, Unno et al. (1999) reported that the small (≈3 mmHg) increase in fetal arterial BP which occurs between 120 and 126 days gestation in intact fetuses was not present in bilaterally adrenalectomised fetuses. This study did not, however, compare arterial BP in adrenalectomised and intact fetuses during later gestation when fetal cortisol concentrations are normally high. The aim of the present study, therefore, was to compare the effects of suppression of endogenous cortisol biosynthesis at two stages in late gestation, i.e. before and after the start of the prepartum increase in fetal cortisol on fetal arterial BP. We have used the agent metyrapone, which is a competitive inhibitor of the steroidogenic enzyme 11β-hydroxylase, to inhibit cortisol synthesis in the sheep fetus (Lye & Challis 1984). 11β-Hydroxylase is the last enzyme in the biosynthetic pathway for cortisol and catalyses the formation of cortisol from 11-desoxycortisol. We have infused metyrapone into fetal sheep starting at 125 days gestation (when fetal cortisol concentrations are low) and at 137 days gestation (when fetal cortisol concentrations are increasing) and measured the fetal plasma cortisol, 11-desoxycortisol and ACTH concentrations, fetal systolic, diastolic and mean arterial BP, and heart rate. We have also investigated whether infusion of metyrapone from 137 days gestation blunts the fetal arterial BP responses to increasing doses of AII. Finally we have investigated the effect of a continuous infusion of metyrapone into fetal sheep between 125 and 140 days gestation on basal fetal arterial BP and heart rate and on the arterial BP responses to increasing doses of AII at 138-139 days gestation.

METHODS

Animals and surgery

All experiments were carried out according to the guidelines of the University of Adelaide Animal Ethics Committee.

Thirty pregnant Merino ewes were used in this study. They were housed in single crates and kept in a 12 h light:12 h dark cycle. Animals were fed once daily and were given water ad libitum throughout the entire length of the protocol. Ewes were fasted 24 h prior to surgery. Antibiotics (2 ml I.M.; Ilium Penstrep, 250 mg ml−1 procaine penicillin, 250 mg ml−1 dihydrosteptomycin sulphate, 20 mg ml−1 procaine hydrochloride; Troy Laboratories, Smithfield, Australia) were administered to each ewe prior to surgery. Surgery was performed under general anaesthesia and aseptic conditions at 119-120 days gestation as previously described (Edwards et al. 1999). General anaesthesia was induced using an intravenous injection of sodium thiopentone (0.5 ml (kg body weight)−1; Pentothal, Rhone Merieux, Pinkenba, Australia) and maintained throughout surgery with 3-4 % halothane (Flurothane, ICI, Melbourne, Australia) in oxygen (Linde Gas, Pinkenba). Single lumen polyvinyl catheters (outer diameter, 1.52 mm; inner diameter, 0.86 mm; Critchley Electrical Products, Silverwater, Australia) were inserted into a fetal carotid artery and into a fetal jugular vein. Vascular catheters were secured to the fetal skin at the neck. A catheter was also inserted into the amniotic cavity (outer diameter, 2.7 mm; inner diameter, 1.5 mm) and was secured to the ear of the fetus. Antibiotics (2 ml I.M; Troy Laboratories) were administered to the fetus during surgery. The fetal head was then replaced into the uterus and the uterus and membranes were closed (Vicryl 1, Ethicon, Johnson & Johnson, Sydney, Australia). Catheters were exteriorised through a small incision on the ewe's flank, the midline incision was then closed (Vicryl 2, Ethicon, Johnson & Johnson) and the abdominal fat layer was also closed (Vicryl 2). Finally the skin of the ewe was closed (Vetafil, 0.3 mm; WDT, Garbsen, Germany). Ewes were allowed to recover from surgery for 5 days before the start of the experimental protocol.

Experimental protocols

Effect of metyrapone infusion from 125 days on fetal arterial blood gas status, plasma hormone concentrations and arterial blood pressure

At 125 days gestation metyrapone (65 μmoles h−1 (kg body weight)−1 in 0.6 M tartaric acid; n = 10; Aldright Chemical Co, Milwaukee, WI, USA), or vehicle (tartaric acid 0.6 M h−1; n = 11; BDH Laboratory Supplies, Poole, Dorset, UK) was infused (0.4 ml h−1; Graseby Medical syringe driver M5-10A, Selby Scientific & Medical, Australia) into the fetal jugular vein. Tartaric acid was used to aid the solubility of metyrapone (Lye & Challis, 1984) and fetal weight at 125 days gestation (3.08 kg) was estimated using fetal growth curves previously published from our laboratory (Edwards et al. 1999):

The infusion was maintained continuously for 15 days until post mortem at 140 days gestation. On the first day of the infusion, fetal arterial blood was collected at 10.00 h (-60 min) and 11.00 h (0 min), prior to the start of the infusion. Fetal arterial blood samples (2.5 ml) were collected throughout the infusion period between 09.00 h and 11.00 h, for blood gas and plasma hormone analysis. In addition, to monitor fetal health and well-being fetal arterial blood gases were determined on alternate days throughout the entire experimental protocol in the tartaric acid- and metyrapone-infused groups and were in the range previously reported for healthy fetal sheep in late gestation (Edwards et al. 1999). Blood samples were centrifuged at 1500 g for 10 min, and the plasma was separated and frozen at -20 °C until analysis. Blood (0.5 ml) was analysed for fetal arterial PO2, PCO2, pH, oxygen saturation (SO2) and haemoglobin content (Hb) using an ABL 520 blood gas analyser (Radiometer, Copenhagen, Denmark).

In all metyrapone- and vehicle-infused fetuses, the fetal carotid artery and amniotic catheters were attached directly to displacement pressure transducers and a quad bridge amplifier (ADInstruments, Castle Hill, Australia). Fetal arterial BP and intra-amniotic pressures were measured continuously for a 5 h period (between 10.00 and 15.00 h) on either 126 days (n = 12) or 127 days gestation (n = 7), i.e. between 24 and 48 h after the start of the infusion period. Fetal arterial BP and intra-amniotic pressures were also measured continuously for 5 h, (between 10.00 h and 15.00 h) at 137, 138 or 139 days (i.e. at 12-14 days after the start of either the metyrapone or vehicle infusion at 125 days gestation). Due to technical difficulties, including blocked fetal arterial catheters on experimental days, not all fetuses had blood pressure recorded at both gestational age ranges (for details of animal numbers in each protocol, see Table 1). Pressures were recorded using Maclab Chart software on a Power Macintosh computer as described previously (Edwards et al. 1999). Fetal systolic and diastolic BP were calculated after subtraction of the intra-amniotic pressure. A mean value for systolic BP, diastolic BP and heart rate for a 5 s interval was calculated at the start of the BP recording and subsequently at 30 min intervals after the first time point. Fetal mean arterial BP was calculated from the formula:

Table 1.

Details of the numbers of animals included in each exdperimental group

| Tartaric acid infused from 125 days gestation | Metyrapone infused from 125 days gestation | Metyrapone infused from 137/138 days gestation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surgery | 11 | 10 | 9 |

| Singleton (S)/twin (T) pregnancies | S(9), T(2) | S(10) | S(7), T(2) |

| Sex | M(3), F(7) | M(4), F(4), | M(5), F(4) |

| unknown(1) | unknown(2) | ||

| Measurement of arterial BP at 126-127 days | 9 | 10 | Not applicable |

| Measurement of arterial BP at 137-139 days | 6 | 7 | 7 |

| AII administration at 137-139 days | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| Measurement of fetal plasma ACTH at 125-128 days | 7 | 8 | Not applicable |

| Measurement of fetal plasma 11-desoxycortisol at 125-128 days | 7 | 9 | Not applicable |

| Measurement of fetal plasma cortisol at 125-128 days | 7 | 9 | Not applicable |

| Measurement of fetal plasma ACTH at 137-140 d | 6 | 9 | 8 |

| Measurement of fetal plasma 11-desoxycortisol at 137-140 days | 6 | 9 | 8 |

| Measurement of fetal plasma cortisol at 137-140 days | 6 | 9 | 8 |

| Measurement of fetal plasma glucose | 8 | 10 | 7 |

| Measurement of maternal plasma progesterone at 137-140 days | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Measurement of fetal organ weights at 140-141 days | 6 | 7 | 8 |

The rate pressure product (RPP) was calculated from the formula (Hawkins et al. 2000):

Effect of metyrapone infusion from 137/138 days on fetal arterial blood gas status, plasma hormone concentrations and fetal arterial BP at 137-139 days gestation

At 137 days or 138 days metyrapone (65 μmol h−1 (kg body weight)−1 in 0.6 M tartaric acid, n = 9) was infused (0.4 ml h−1; Graseby Medical syringe driver M5-10A) into the fetal jugular vein (Table 1). Fetal weight at this age range (4.69 kg) was also estimated using fetal growth curves previously published from our laboratory (Edwards et al. 1999). The infusion was maintained continuously until post mortem at either 140 or 141 days gestation. On the first day of the infusion period fetal arterial blood (3.5 ml) was collected at 09.00 h (-3 h) and 12.00 h (0 h) and at 6, 21, 24, 45 and 69 h after the start of the infusion. Fetal arterial blood gases remained in the range previously reported for healthy fetal sheep in late gestation (Edwards et al. 1999).

Fetal arterial BP and intra-amniotic pressure were measured from 09.00 h (3 h before the start of the metyrapone infusion) until 18.00 h (6 h after the start of metyrapone infusion). Fetal arterial BP and intra-amniotic pressure were then measured continuously from 21 h to 27 h after the start of the infusion (i.e. between 09.00 h and 15.00 h on the following day). Fetal systolic and diastolic BP were calculated after subtraction of the intra-amniotic pressure. A mean value for systolic and diastolic BP and heart rate was determined for one 5 s interval for every 15 min between -3 h and the start of the infusion (time 0). Mean 5 s values for BP were also determined at 15 or 30 min intervals between 0 and +6 h and subsequently at 21-27 h after the start of the infusion.

Fetal arterial BP responses to AII

Fetal arterial BP responses to increasing doses of AII were measured at 138 or 139 days gestation in fetuses infused with either metyrapone (n = 7) or vehicle (n = 7) from 125 days gestation and in fetuses infused with metyrapone (n = 7) starting on 137 or 138 days (Table 1). Bolus doses of human AII (0.2, 0.75, 1.5, 3, 5 and 10 μg; Peninsula Laboratories Inc, Belmont, CA, USA) were injected intravenously in a random order. There was a 20 min period between administrations of each AII dose. For each fetus, the AII doses were calculated relative to fetal weight as determined at post mortem.

Post mortem and tissue collection

At 140 or 141 days, all ewes were killed using a lethal injection of sodium pentobarbitone (Lethabarb; 25 ml at 325 mg ml−1; Vibrac Australia, Peakhurst, Australia). The uterus was removed and the fetus removed by hysterotomy. Fetal weight, and crown rump length were measured and fetal organs were removed and weighed.

Radioimmunoassays

ACTH

Fetal plasma immunoreactive ACTH concentrations were measured using a radioimmunoassay kit (ICN Biomedicals, Australia), which has been validated previously for use in fetal sheep plasma (McMillen et al. 1990). According to the manufacturer, the cross-reactivity of the rabbit anti-human ACTH 1-39 was < 1 % with β-endorphin, α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone, α-lipotrophin, and β-lipotrophin. The sensitivity of the assay was 9 pg ml−1. The intra-assay coefficient of variation was < 5 % and the inter-assay coefficient of variation was < 15 %.

Cortisol

Fetal plasma samples from metyrapone- and vehicle-infused fetuses were extracted and assayed in duplicate. Briefly, cortisol was extracted from the plasma using dichloromethane as described previously (Bocking et al. 1986). The efficiency of the recovery was > 85 %. Samples were then reconstituted in assay buffer (Tris hydrochloride; bovine serum albumin; sodium azide). Standards were serially diluted in assay buffer, from a stock (100 nmol l−1) solution (range 0.78-100 nmol l−1). Anti-cortisol (100 μl; 1:15 dilution; Orion Diagnostica, Turku, Finland) was added followed by 125I-labelled cortisol (100 μl; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, UK). Tubes were vortexed and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h before the addition of goat anti-rabbit serum (initial dilution 1:30; 100 μl) and polyethylene glycol (1ml; 20 %; BDH Laboratory Supplies). Tubes were vortexed before centrifugation at 3700 g and 4 °C for 30 min. The supernatant was aspirated and the precipitate counted on a gamma counter (Packard, Downers Grove, IL, USA). Extracted cortisol from increasing volumes of fetal sheep plasma was quantitatively recovered (114.8 ± 7.6 %) and the relationship between expected concentration of cortisol (x) and the observed concentration of cortisol (y) in increasing volumes of extracted fetal sheep plasma was described by the equation y = 1.5x - 0.86 (r = 0.983, P < 0.003). The sensitivity of the assay was 0.2 nmol l−1 and, according to the manufacturer, the cross-reactivity of the rabbit anti-cortisol antisera was < 1 % with pregnenolone, aldosterone, progesterone and oestradiol. The cross-reactivity of the anti-cortisol with 11-desoxycortisol (Sigma Chemical Co, St Louis, MO, USA) was determined to be 3.7 % across the range of values measured in the current study. The intra-assay coefficient of variation was < 5 % and the inter-assay coefficient of variation was < 20 %.

11-Desoxycortisol

Fetal plasma 11-desoxycortisol concentrations were measured using a radioimmunoassay kit (ICN Biomedicals). Due to the higher concentration of 11-desoxycortisol present in the fetal plasma samples collected from metyrapone-infused animals, these samples were diluted in assay buffer (1:10; 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline; Sigma Chemical Co, St Louis, MO, USA; 0.1 % BSA and 0.1 % NaN3; BDH Laboratory Supplies) prior to extraction, whereas samples from vehicle-infused animals, did not require dilution prior to extraction. 11-Desoxycortisol was extracted from standard solutions (10 μl), and plasma samples (2-100 μl) using dichloromethane (Bocking et al. 1986), and the efficiency of extraction was > 95 %. Extracted standards and samples were then reconstituted in buffer (10 μl), and 100 μl of buffer was then added in place of steroid globulin binding inhibitor and the remainder of the assay was then performed according to the manufacturer's directions (ICN BioMedicals). Extracted 11-desoxycortisol from increasing volumes of fetal sheep plasma was quantitatively recovered (105.4 ± 5.6 %). The relationship between the expected concentration of 11-desoxycortisol (x) and the observed concentration of 11-desoxycortisol (y) in increasing volumes of fetal sheep was described by the equation y = 1.2x - 2.6 (r = 0.999, P < 0.001). The rabbit anti-human 11-desoxycortisol was specified by the manufacturer to have a cross-reactivity of < 0.3 % with progesterone and pregnenolone sulphate. The cross-reactivity of the anti-11-desoxycortisol with cortisol was determined to be 0.25 %. The mean binding of the anti-11-desoxycortisol to 125I-labelled 11-desoxycortisol in the absence of antigen was 67.4 ± 1.1 %. The sensitivity of the assay was 0.5 nmol l−1. The intra-assay coefficient of variation was < 5 % and the inter-assay coefficient of variation was < 15 %. For all plasma samples, the amount of cortisol and 11-desoxycortisol in each sample was then calculated using the following equations:

where X is the ‘actual’ amount of cortisol, Y is the ‘actual’ amount of 11-desoxycortisol, a is the measured value of cortisol in a sample using the cortisol assay and b is the measured value of 11-desoxycortisol in a sample using the 11-desoxycortisol assay.

Progesterone

Maternal plasma progesterone concentrations were measured between 137 and 140 days gestation after intrafetal infusion of tartaric acid from 125 days (n = 5), intrafetal infusion of metyrapone from 125 days (n = 5) and intrafetal infusion of metyrapone from 137 days gestation (n = 5). Plasma progesterone concentrations were measured using a radioimmunoassay kit (ICN Biomedicals) according to the manufacturer's directions, except that the anti-progesterone antibody was diluted 1:3 before addition to the assay. According to the manufacturer, the cross-reactivity of the rabbit anti-human progesterone was 5.4 % 20a-dihydroprogesterone; 3.8 % desoxycorticosterone, < 1 % corticosterone, 17a-hydroxyprogesterone and pregnenolone, and < 0.01 % with cortisol and 11-desoxycortisol. The sensitivity of the assay was 0.06 ng ml−1. The intra-assay coefficient of variation was < 5 % and the inter-assay coefficient of variation was < 16 %.

Glucose

Plasma concentrations of glucose were determined by enzymatic analysis using hexokinase and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase to measure the formation of NADH photometrically at 340 nm (COBAS MIRA automated analysis system, Roche Diagnostica, Basel, Switzerland). The intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation were both less than 5 %.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (S.E.M.).

Blood gas data

The mean values of fetal arterial PO2, PCO2, pH, SO2 and Hb were compared in the metyrapone- and vehicle-infused groups from the day before until 72 h after the start of the infusion using Student's t test.

Effect of metyrapone infusion from 125 days

Fetal plasma glucose concentrations were compared between the vehicle- and metyrapone-treated groups before (125 days) and after (126/127 days) the start of the infusion period using multifactorial ANOVA and repeated measures and the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSSX, Chicago, IL, USA) on a VAX mainframe computer system. The daily changes in fetal plasma ACTH, 11-desoxycortisol and cortisol concentrations were calculated by subtracting the average baseline value during the day before the start of the infusion at 125 days gestation from the plasma hormone concentrations during the first 72 h of the infusion period. The changes in plasma hormone concentrations after the start of the infusion period were compared between the vehicle- and metyrapone-infused groups using a multifactorial ANOVA and repeated measures. Fetal plasma ACTH, 11-desoxycortisol and cortisol concentrations and maternal plasma progesterone concentrations in the metyrapone- and vehicle-infused groups were compared at 137-139 days, using a multifactorial ANOVA with repeated measures.

Fetal arterial BP, heart rate and rate pressure product in the metyrapone- and vehicle-infused groups were also compared using a multifactorial ANOVA with repeated measures. Factors included in the ANOVA were group (metyrapone- vs. vehicle-infused), gestational age range (126-127 days and 137-139 days) and time points during the BP recording (i.e. every 30 min between 10.00 h and 15.00h). Where the ANOVA identified significant interactions between main effects, the data were split on the basis of the interaction and re-analysed.

Effect of metyrapone infusion from 137/138 days

Fetal plasma ACTH, 11-desoxycortisol and cortisol concentrations in the fetuses infused with vehicle and in the metyrapone-infused fetuses were compared between 137 and 140 days gestation using a multifactorial ANOVA with repeated measures. Changes in fetal arterial BP, heart rate and rate pressure product relative to the start of the metyrapone infusion were also determined using ANOVA with repeated measures. Fetal plasma glucose concentrations were compared before and after the start of the metyrapone infusion at 137/138 days and plasma glucose concentrations were also compared between all three treatment groups at 139-140 days gestation using a one-way ANOVA.

Comparison of the effects of metyrapone infusion from 125 days and from 137/138 days

Systolic, diastolic and mean arterial BP, heart rate and rate pressure product measured between 10.00 h and 15.00 h on either 138 or 139 days were compared between fetuses infused with metyrapone from 125 days, with metyrapone from 137 days and with vehicle from 125 days using a multifactorial ANOVA with repeated measures. The main factors included treatment group and time points (i.e. every 30 min between 10.00 h and 15.00 h on the day of BP recording).

Fetal arterial BP responses to AII

The mean systolic or diastolic BP value before the first dose of AII was used as the baseline for responses to all subsequent doses. The maximum systolic and diastolic BP response within 2 min of the injection of each dose of AII was determined. The change in BP from baseline was then calculated by subtracting the baseline recording from the maximum BP response for that dose. The data were then analysed using a multifactorial ANOVA with repeated measures. The factors included in the ANOVA were experimental group (metyrapone infused from 125 days, metyrapone infused from 137 days and vehicle-infused fetuses) and the dose of AII (< 0.1 μg (kg body weight)−1 to 4.0 μg (kg body weight)−1). When a significant interaction between major factors was identified by ANOVA, the data were split on the basis of the interacting factor and re-analysed. Fetal plasma glucose concentrations in the three treatment groups at 139-140 days gestation were compared using a one-way ANOVA.

In all analyses where ANOVA identified significant differences between groups, Duncan's multiple range post-hoc test was used to identify the differences between mean values. A probability of < 5 % (P < 0.05) was taken to be significant.

RESULTS

Effect of metyrapone infusion from 125 days on fetal plasma hormone concentrations, arterial BP and heart rate at 126-128 days gestation

During the first 72 h after the start of the infusion period at 125 days gestation, there were no differences between the metyrapone- and vehicle-infused groups in the mean values of arterial PO2 (metyrapone, 22.8 ± 0.7 mmHg; vehicle, 22.4 ± 0.9), PCO2 (metyrapone, 45.9 ± 1.0 mmHg; vehicle, 46.7 ± 1.2 mmHg), pH (metyrapone, 7.398 ± 0.007; vehicle, 7.404 ± 0.004), SO2 (metyrapone, 72.2 ± 2.0 %; vehicle, 70.8 ± 2.7 %) and Hb (g dl−1) (metyrapone, 10.4 ± 0.2; vehicle, 10.0 ± 0.3).

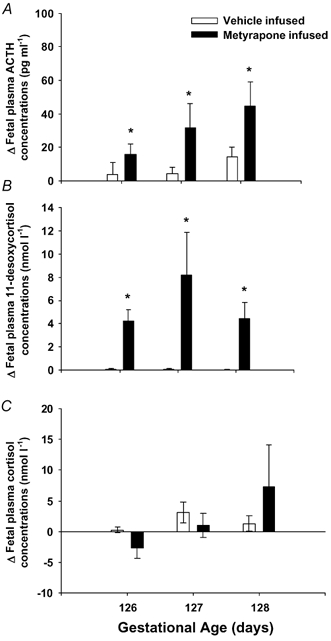

Before the start of the infusion period, there were no significant differences in plasma glucose, ACTH, 11-desoxycortisol or cortisol concentrations between fetuses assigned to the metyrapone- (glucose, 1.10 ± 0.06 mmol l−1; ACTH, 92 ± 21.2 pg ml−1; 11-desoxycortisol, 0.9 ± 0.07 nmol l−1; cortisol, 5.3 ± 1.7 nmol l−1) and vehicle-infused groups (glucose, 1.14 ± 0.09 mmol l−1; ACTH, 67 ± 9.3 pg ml−1; 11-desoxycortisol, 0.8 ± 0.06 nmol l−1; cortisol, 2.6 ± 0.4 nmol l−1). After the start of the infusion period there was no difference in fetal plasma glucose concentrations between the metyrapone- (1.00 ± 0.05 mmol l−1) and vehicle-treated groups (1.10 ± 0.06 mmol l−1) at 126- 127 days gestation. Between 24 and 72 h after the start of the infusion, fetal plasma ACTH concentrations were significantly higher (F = 7.07; P < 0.05) in metyrapone-infused (change from baseline at 72 h, 44.6 ± 14.2 pg ml−1) when compared with vehicle-infused fetuses (change from baseline at 72 h, 14.6 ± 5.6 pg ml−1) (Fig. 1). Plasma 11-desoxycortisol concentrations were also significantly increased above baseline concentrations by 24 h after the start of the metyrapone infusion and were higher throughout the first 72 h of the infusion (F = 9.58, P < 0.01) than in vehicle-infused fetuses (Fig. 1). While plasma cortisol concentrations tended to fall within 24 h of the start of the metyrapone infusion (-2.7 ± 1.7 nmol l−1) compared to the vehicle-infused fetuses (0.3 ± 0.4 nmol l−1), there was no difference between the two groups either in plasma cortisol concentrations or in the change in plasma cortisol concentrations during the first 72 h of the infusion period (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Changes in fetal plasma ACTH, 11-desoxycortsiol and cortisol concentrations at 126-128 days after the start of infusion of metyrapone (filled bar) or vehicle (open bar).

There was a significant increase in both plasma ACTH (A) and 11-desoxycortisol (B) from pre-infusion levels in metyrapone-infused fetuses and when compared with vehicle-infused controls. * Hormone values which are significantly higher in the metyrapone- than in the vehicle-infused group (P < 0.05).

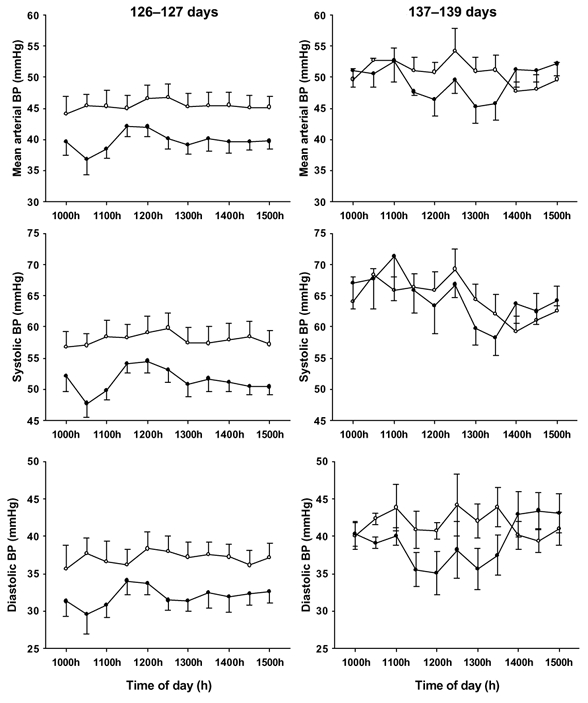

At 24-48 h after the start of the infusion, fetal systolic BP (F = 6.69; P < 0.02), diastolic BP (F = 4.73; P < 0.05) and mean arterial BP (F = 6.21; P < 0.03) were significantly lower in the metyrapone-infused group when compared to vehicle-infused controls (F = 6.69; P < 0.02) (Fig. 2A-C). There was also a significant inverse relationship between systolic (y = -0.17x + 72, r2 = 0.86, P < 0.01), diastolic (y = -0.18x + 49.2, r2 = 0.93, P < 0.005) and mean arterial BP (y = -0.18x + 58.2, r2 = 0.94, P < 0.001) and plasma ACTH concentrations in the vehicle-, but not metyrapone-infused, fetuses.

Figure 2. Fetal systolic, diastolic and mean arterial BP between 10.00 h and 15.00 h at 126-127 days gestation (left) and 137-139 days gestation (right) in fetuses infused with metyrapone (•) or vehicle (○) from 125 days gestation.

Fetal systolic, diastolic and mean arterial BP values were significantly lower (P < 0.05) in the metyrapone- than vehicle-infused fetuses at 126-127 days, but not at 137-139 days gestation.

There was no effect of metyrapone infusion on fetal heart rate at 126-127 days gestation (metyrapone-infused, 167 ± 5 beats min−1; vehicle-infused, 173 ± 6 beats min−1) but the rate pressure product was significantly lower (F = 6.89; P < 0.02) in metyrapone-infused (8.7 ± 0.4 mmHg beats min−1) compared to vehicle-infused fetuses (9.9 ± 0.5 mmHg beats min−1) at 126-127 days gestation.

Effect of metyrapone infusion from 125 days on plasma ACTH and cortisol concentrations, fetal arterial BP and heart rate at 137-140 days gestation

At 137-139 days gestation, i.e. at 12-14 days after the start of the metyrapone infusion, plasma ACTH (F = 11.9, P < 0.01) and 11-desoxycortisol (F = 80.9, P < 0.001) concentrations remained significantly higher in fetuses infused with metyrapone from 125 days gestation (ACTH 235.9 ± 74.1 pg ml−1; 11-desoxycortisol 21.5 ± 7.1 nmol l−1) when compared to vehicle-infused fetuses (ACTH 79.9 ± 15.6 pg ml−1; 11-desoxycortisol 1.1 ± 0.2 nmol l−1). There was no significant difference at 137-139 days, however, between plasma cortisol concentrations in metyrapone- (36.9 ± 20.6 nmol l−1) and vehicle-infused fetuses (14.1 ± 3.1 nmol l−1). There was also no significant difference in maternal plasma progesterone concentrations between the metyrapone- (6.7 ± 1.6 ng ml−1) and vehicle-infused groups (7.3 ± 1.6 ng ml−1) at 137-140 days gestation.

At 137-139 days gestation, systolic, diastolic and mean arterial BP values were not different between the metyrapone- and vehicle-infused groups (Fig. 2D-F). In both the metyrapone- and vehicle-infused groups, systolic, diastolic and mean arterial BP were significantly higher (P < 0.001) at 137-139 days gestation when compared to 126-127 days.

There was no difference in fetal heart rate (metyrapone-infused, 145 ± 7 beats min−1; vehicle-infused, 148 ± 8 beats min−1) or the rate pressure product (metyrapone-infused, 9.4 ± 0.7 mmHg beats min−1; vehicle-infused, 9.5 ± 0.5 mmHg beats min−1) between the two treatment groups at 137-139 days gestation.

Effect of metyrapone infusion from 137/138 days on plasma glucose and hormone concentrations, fetal arterial BP and heart rate at 137-140 days gestation

There were no significant changes in fetal arterial PO2 (pre-infusion, 21.3 ± 0.7 mmHg; infusion, 20.3 ± 1.1 mm Hg), PCO2 (pre-infusion, 48.6 ± 0.6 mmHg; infusion, 50.1 ± 1.1 mmHg), pH (pre-infusion, 7.401 ± 0.004; infusion, 7.396 ± 0.006) and Hb (pre-infusion, 9.9 ± 0.5 g dl−1; infusion, 10.3 ± 0.6 g dl−1) during the first 72 h of the metyrapone infusion when compared with pre-infusion values. There was a small but significant decrease in arterial O2 saturation (pre-infusion, 65.5 ± 2.2 %; infusion, 57.5 ± 3.8 %) during the metyrapone infusion period. There was a significant fall (P < 0.005) in fetal plasma glucose concentrations after the start of the metyrapone infusion (pre-infusion, 1.36 ± 0.04 mmol l−1; +24-48 h, 1.09 ± 0.07 mmol l−1).

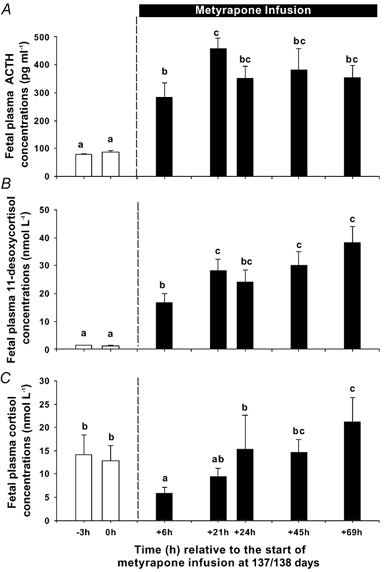

There was a significant interaction between the effects of metyrapone and vehicle infusion and day of infusion on plasma cortisol, ACTH and 11-desoxycortisol concentrations. In the vehicle-infused group, there was no change in plasma cortisol, ACTH or 11-desoxycortisol concentrations between 137 and 140 days gestation. In the metyrapone group there was a significant fall in fetal plasma cortisol concentrations during the first 6 h of the infusion, followed by a rise in plasma cortisol back to pre-infusion values by 24 h after the start of the infusion (Fig. 3). Plasma cortisol concentrations were higher than pre-infusion values by the third day of metyrapone infusion. Plasma ACTH and 11-deoxycortisol concentrations were significantly higher than pre-infusion values after the start of the metyrapone infusion and remained elevated throughout the remainder of the infusion period (Fig. 3). There was no significant change in maternal plasma progesterone concentrations after the start of the intrafetal metyrapone infusion at 137/138 days gestation (pre-infusion, 6.3 ± 1.3 ng ml−1; +6 h infusion, 6.3 ± 1.1 ng ml−1)

Figure 3. Plasma ACTH (A), 11-desoxycortisol (B) and cortisol (C) concentrations before and after the start of metyrapone infusion at 137 days gestation.

Different letters above the bars denote mean values, which are different from each other (P < 0.05).

Fetal systolic, diastolic and mean arterial BP and heart rate did not change significantly during first 27 h of the metyrapone infusion period. At 137-139 days gestation, there was no difference in fetal systolic, diastolic and mean arterial BP, heart rate and rate pressure product between the groups of fetuses infused with vehicle from 125 days, metyrapone from 125 days or with metyrapone from 137/138 days (Table 2).

Table 2.

Fetal systolic, diastolic and mean arterial BP, heart rate and rate pressure product at 137-139 days gestation in fetuses infused with metyrapone from 125 days, with metyrapone from 137/138 days, or with vehicle.

| Tartaric acid infused from 125 days (n = 6) | Metyrapone infused from 125 days (n = 7) | Metyrapone infused from 137/138 days (n = 7) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 64.4 ± 2.9 | 64.4 ± 3.3 | 60.7 ± 3.0 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 41.6 ± 2.1 | 39.3 ± 2.5 | 38.8 ± 2.5 |

| Mean BP (mmHg) | 50.7 ± 2.0 | 49.4 ± 2.2 | 47.6 ± 2.6 |

| Heart rate (beats min-1) | 148 ± 8 | 145 ± 7 | 153 ± 9 |

| Rate pressure product (mmHg beats min-1) | 9.5 ± 0.5 | 9.4 ± 0.7 | 9.4 ± 0.7 |

Fetal arterial BP responses to AII

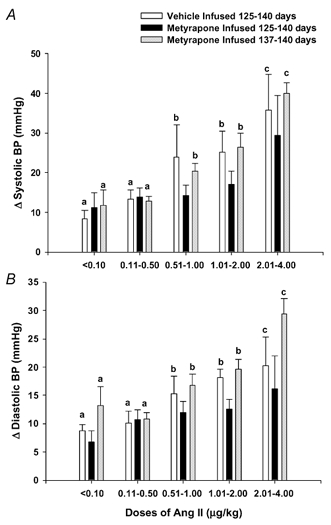

The fetal arterial BP response to AII at 137-139 days gestation was significantly different between the group of fetuses infused with metyrapone from 125 days gestation when compared with the groups either infused with vehicle from 125 days, or with metyrapone from 137/138 days gestation, i.e. there was a significant interaction (P < 0.01) between the effects of treatment group and AII. In fetuses infused with either vehicle from 125 days, or with metyrapone from 137/138 days, fetal systolic, diastolic and mean arterial BP increased with increasing doses of AII. In fetuses infused with metyrapone from 125 days, however, the fetal arterial BP responses to AII did not increase with increasing doses of AII at 137-139 days gestation (Fig. 4). At this age range, there was no difference in the plasma glucose concentrations in fetuses infused with vehicle from 125 days (0.89 ± 0.18 mmol l−1), with metyrapone from 125 days (0.92 ± 0.11 mmol l−1) or with metyrapone from 137 days gestation (1.09 ± 0.07 mmol l−1).

Figure 4. Fetal arterial blood pressure responses to increasing doses of AII at 138-139 days in fetuses infused with vehicle from 125 days gestation (open bars), metyrapone from 125 days gestation (filled bars) or with metyrapone from 137/138 days (grey bars) gestation.

Different letters above the bars denote mean arterial BP responses which are significantly different from other values within a treatment group (P < 0.05).

Fetal outcomes

Fetal body weights were not significantly different between the fetuses infused with metyrapone from either 125 days or from 137/138 days gestation or with vehicle (Table 3). At 140-141 days gestation, the relative weight of the combined adrenal weights was significantly higher in fetuses infused with metyrapone from either 125 days or from 137/138 days gestation when compared with the vehicle-infused group (Table 3). The relative total kidney weight was also significantly higher in the fetuses infused with metyrapone from 125 days than in the other two treatment groups. The relative liver weight was also higher in fetuses infused with metyrapone from 125 days when compared with fetuses infused with metyrapone from 137/138 days gestation.

Table 3.

Summary of th relative organ weights from singleton featuses infused with vehicle or metyrapone from 125 days and singleton fetuses infused with metyrapone from 137/138 days, at 140/141 days generation

| Tartaric acid infused from 125 days gastation (n = 6) | Metyrapone infused from 125 days gestation (n = 7) | Metyrapone infused from 137/8 days gestation (n = 8) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fetal weight (kg) | 4.5 ± 0.3 | 4.7 ± 0.3 | 4.8 ± 0.3 |

| Total adrenal:body weight (g kg-1) | 0.11 ± 0.01* | 0.18 ± 0.03† | 0.16 ± 0.01*† |

| Total kidney:body weight (g kg-1) | 5.8 ± 0.3* | 7.9 ± 0.7† | 6.1 ± 0.3* |

| Heart:body weight (g kg-1) | 6.5 ± 0.3 | 6.8 ± 0.2 | 7.0 ± 0.2 |

| Lung:body weight (g kg-1) | 29.8 ± 1.5 | 31.2 ± 1.4 | 29.2 ± 1.7 |

| Liver: body weight (g kg-1) | 26.4 ± 2.4*† | 32.5 ± 3.3† | 24.2 ± 0.9* |

| Anterior pituitary: body weight (g kg-1) | 0.028 ± 0.001 | 0.025 ± 0.001 | 0.028 ± 0.002 |

Mean values which are significantly different (P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

We have investigated the effect of infusion of metyrapone, an inhibitor of endogenous cortisol biosynthesis, on the maintenance of arterial BP in the fetal sheep at two stages in late gestation when fetal cortisol concentrations are either low (126-128 days) or increasing at the onset of the prepartum cortisol surge (137-139 days).

Cortisol, ACTH and fetal arterial BP at 125-128 days gestation

When metyrapone was infused from 125 days, we found that there was no significant change in fetal plasma cortisol concentrations during the first 72 h of the infusion period. There was, however, a significant increase in fetal plasma ACTH and 11-desoxycortisol during this period. This suggests that there was a decrease in circulating cortisol prior to the collection of the first fetal blood sample at +24 h which resulted in the stimulation of ACTH secretion. The increase in ACTH was maintained throughout the first 72 h of the infusion period, indicating that higher ACTH concentrations were required to overcome the metyrapone-induced block of adrenal 11β-hydroxylase and restore circulating cortisol concentrations to pre-infusion values. While the initial fall in circulating cortisol concentrations may have been transient, systolic, diastolic and mean arterial BP were significantly lower in metyrapone- than in vehicle-infused fetuses at 24-48 h after the start of the infusion. The mean arterial BP in metyrapone-infused fetuses was 5-6 mmHg lower than in the vehicle-infused group. Unno et al. (1999) reported that fetal arterial BP increased by ≈3 mmHg between 120 and 126 days gestation in intact, but not adrenalectomised, fetuses and that this occurred when plasma cortisol concentrations were below the detection limit of the cortisol radioimmunoassay in both of these groups at this gestational age range (Unno et al. 1999). In the current study, there was a significant inverse correlation between fetal arterial BP and fetal plasma ACTH concentrations in the vehicle-infused fetuses at 126-127 days gestation. Cortisol is measured after extraction of total cortisol, i.e. cortisol bound to corticosteroid binding globulin and ‘free’ cortisol from fetal plasma. One possibility is that in the control group, increases in circulating concentrations of ‘free’ cortisol result in a concomitant increase in arterial BP and an inhibition of fetal ACTH secretion. These data in the control group and the decrease in arterial BP measured in the metyrapone-infused fetuses suggest that cortisol may contribute to the regulation of fetal arterial BP during this period in gestation when fetal plasma cortisol concentrations are relatively low. Any actions of cortisol at these low concentrations would be through occupancy of the high-affinity type I glucocorticoid receptor (MR), rather than the low-affinity type II glucocorticoid receptor (GR). While MRs are expressed in the fetal sheep kidney (Moritz et al. 2002) in late gestation, the presence of the enzyme 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 (11β-HSD-2), which metabolises cortisol to the inactive cortisone, may protect the renal MR from glucocorticoid occupancy (Langlois et al. 1995; McMillen et al. 2000). In the adult, MRs and GRs are each present in the aorta, mesenteric artery and vascular smooth muscle cells (Lombès et al. 1992; Kornel et al. 1993; Takeda et al. 1995) and there is evidence that glucocorticoids act in vascular smooth muscle to modify the actions of vasoactive agents, including the catecholamines, AII, nitric oxide and prostaglandins (Falardeau & Martineau 1989; Rees et al. 1990; Pirpiris et al. 1992; Walker & Williams, 1992; Wehling et al. 1995; Muto et al. 1996). It has been previously demonstrated that there was a small but significant decrease in fetal arterial BP in response to a specific AT1 receptor antagonist at 128 days gestation and that intrafetal infusion of cortisol resulted in a further fall in arterial BP in response to the AT1 receptor antagonist (Forhead et al. 2000). One possibility therefore is that at 126-127 days gestation, a transient fall in plasma cortisol results in a decrease in arterial BP as a result of a decrease in the vascular responsiveness to the actions of circulating AII.

It is intriguing that fetal arterial BP was lower in the metyrapone fetuses at 24-28 h after the start of the infusion while fetal cortisol concentrations were maintained at pre-infusion values by the increase in fetal ACTH. It could be argued that the inverse relationship between arterial BP and plasma ACTH concentrations in the control group and the association between low arterial BP and high ACTH concentrations in the metyrapone-infused group reflect the actions of ACTH, rather than cortisol, on fetal arterial BP. Infusion of ACTH in the pregnant ewe, however, results in an increase, rather than decrease, in maternal and fetal arterial BP and the increase in fetal BP in these studies was directly associated with an increase in fetal cortisol (Lumbers et al. 1998). Furthermore, a short-term infusion of ACTH (24 h) in fetal sheep at 125-130 days gestation did not significantly alter fetal arterial BP or heart rate (Carter et al. 1993). There is evidence, however, that intrafetal infusion of the cleavage product of ACTH, α-melanocyte stimulating hormone (αMSH), can act to decrease mean arterial BP in the sheep fetus (Llanos et al. 1983). While it is possible that an increase in an ACTH-derived peptide suppressed fetal arterial BP at 126-127 days gestation, fetal ACTH concentrations remained elevated in metyrapone-infused fetuses at 137-139 days gestation, when there was no difference in fetal arterial BP between the metyrapone- and vehicle-infused fetuses.

Cortisol, ACTH and fetal arterial BP at 137-139 days gestation

In the present study, metyrapone was infused in a second cohort of fetuses at a later stage in gestation when fetal cortisol concentrations were higher than at 125 days. In this later cohort, there was a significant decrease in plasma cortisol concentrations by 6 h after the start of the metyrapone infusion and this decrease was associated with an increase in fetal ACTH and 11-desoxycortisol concentrations. Plasma cortisol concentrations were restored to pre-infusion values by 24-48 h after the start of the metyrapone infusion and plasma ACTH and 11-desoxycortisol concentrations remained elevated for the remainder of the infusion period. Interestingly there was also a fall in fetal plasma glucose concentrations in fetuses infused with metyrapone at 137 days, but not 125 days gestation. This is consistent with evidence which suggests that activation of endogenous glucose production in the sheep fetus occurs relatively late in gestation and is dependent on the prepartum increase in fetal cortisol concentrations (Fowden et al. 1993; Fowden et al. 1998). While fetal cortisol concentrations fell to around 5-10 nM, there was no change in fetal mean arterial BP during the first 24 h of the metyrapone infusion and mean arterial BP in the metyrapone- and vehicle-infused fetuses was not different at 138-139 days gestation. A recent study investigated the effect of bilateral fetal adrenalectomy (ADX) on fetal arterial BP regulation in late gestation (Segar et al. 2002). These authors demonstrated that ADX fetuses had undetectable circulating cortisol concentrations and that mean fetal arterial BP was significantly lower at 139-140 days gestation (44 ± 2 mmHg) when compared with ADX fetuses which had received cortisol replacement (53 ± 2 mmHg) (Segar et al. 2002). This latter study did not, however, compare fetal arterial BP in ADX and intact fetuses. One possible interpretation of the available data from the studies on ADX fetuses (Unno et al., 1999; Segar et al. 2002) and on fetuses infused with metyrapone from either 125 or 137 days is that a decrease in circulating cortisol to levels below ≈10 nM is required before there is an impact on mean arterial BP in the sheep fetus. It has previously been shown, however, that fetal or maternal cortisol infusion results in an increase in fetal arterial BP when endogenous cortisol concentrations are low at 120 days gestation (Tangalakis et al. 1992; Jensen et al. 2002) but not when cortisol concentrations are high after 129 days gestation (Tangalakis et al. 1992) and this is evidence that there is a threshold above which fetal cortisol concentrations and mean arterial blood pressure are not directly related during late gestation. Edwards & McMillen (2001) reported that there was a direct relationship between fetal arterial BP and plasma cortisol concentrations between 135 and 145 days gestation when data from fetuses of well-nourished and undernourished ewes were combined. Forhead et al. (2000), however, found that while there was an increase in fetal cortisol between 128 and 140 days gestation, there were no significant differences between plasma AII, renin and angiotensinogen and arterial BP across this age range, although they concluded that this may have been due to wide inter-animal variation. While we have demonstrated that infusion of metyrapone resulted in a fall in fetal arterial BP at 125 days gestation and not at 137 days gestation, it is possible that the fall in fetal plasma cortisol concentrations at 137 days gestation was either too transient or of insufficient magnitude to cause an associated decrease in mean arterial blood pressure.

Fetal arterial BP responses to AII

Plasma cortisol concentrations and arterial BP at 137-139 days gestation were not different in fetuses which had been infused with either metyrapone or vehicle from 125 days gestation. At this gestational age, however, the responsiveness of arterial BP to increasing doses of AII was significantly blunted in fetuses which had been infused with metyrapone from 125 days gestation, when compared with fetuses which had been infused with metyrapone from 137 days gestation or with vehicle from 125 days gestation. The lack of effect of metyrapone infusion from 137 days gestation on the fetal arterial BP responses to AII suggests that the blunted arterial BP response was not due to a non-specific effect of metyrapone. There was also no difference in fetal arterial blood gas status or fetal plasma glucose concentrations between the three treatment groups in this gestational age range. This is the first report, therefore, that infusion of an inhibitor of cortisol biosynthesis at around 125 days gestation results in a subsequent decrease in fetal arterial BP responsiveness to AII. One possibility is that exposure to metyrapone at around 125 days gestation has resulted in a maintained decrease in the expression of the AT1 receptor in the fetal vasculature. Infusion of an AT1 receptor antagonist in fetal sheep at around 128 days gestation results in a decrease in fetal arterial BP and in a greater hypotensive response at 140 days gestation (Forhead et al. 2000). An increase in maternal cortisol (Edwards & McMillen, 2001) and fetal cortisol concentrations (Tangalakis et al. 1992) at around 125 days gestation are also associated with an increase in the fetal arterial BP responses to AII and in a greater hypotensive response to an AT1 receptor antagonist (Forhead et al. 2000). Furthermore, intrafetal cortisol infusion results in an increase in AT1 mRNA expression in the fetal heart (Segar et al. 1995).

Interestingly, infusion of metyrapone from 125 but not 137 days also resulted in a significant increase in fetal kidney weight at 140 days gestation. Around 60 % of total kidney growth occurs over the period between 100 and 130 days gestation (Wintour et al. 1999) and it has been recently demonstrated that unilateral nephrectomy during the period of active nephrogenesis results in compensatory hypertrophy of the remaining kidney in the sheep fetus (Douglas-Denton et al. 2002). One possibility is that the direct or indirect actions of metyrapone on the fetal kidney at around 125 days gestation results in a decrease in nephrogenesis with a consequent hypertrophic response. Alternatively, an increase in fetal cortisol results in a suppression of the expression of insulin-like growth factor II (IGF-II) in the fetal liver and kidney (Li et al. 1993) and it may be that a decrease in circulating cortisol at around 126-127 days gestation resulted in an increase in IGF-II expression in the fetal sheep kidney and/or liver. Infusion of IGF-I results in an increase in fetal liver and kidney size and in renal renin content, and this is not associated with any increase in fetal arterial blood pressure (Lok et al. 1996; Marsh et al. 2001). The specific effect of infusion of metyrapone from around 125 days gestation on fetal vascular responsiveness to AII and on fetal kidney weight in later gestation suggests that there may be a critical window in development, which occurs before the prepartum increase in cortisol, when endogenous fetal cortisol contributes to the maintenance of arterial blood pressure, the development of vascular responsiveness to AII and fetal kidney growth.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Anne Jurisevic and Laura O'Carroll for their expert assistance with animal surgery and animal care and experimentation. We are also grateful to the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia for financial support of these studies.

REFERENCES

- Anwar MA, Schwab M, Poston L, Nathanielsz PW. Betamethasone-mediated vascular dysfunction and changes in hematological profile in the ovine fetus. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:H1137–1143. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.4.H1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bocking AD, McMillen IC, Harding R, Thorburn GD. Effect of reduced uterine blood flow on fetal and maternal cortisol. J Dev Physiol. 1986;8:237–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boddy K, Dawes GS, Fisher R, Pinter S, Robinson JS. Foetal respiratory movements, electrocortical and cardiovascular responses to hypoxaemia and hypercapnia in sheep. J Physiol. 1974;243:599–618. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1974.sp010768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter AM, Richardson BS, Homan J, Towstoless M, Challis JRG. Regional adrenal blood flow responses to adrenocorticotropic hormone in fetal sheep. Am J Physiol. 1993;264:E264–269. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1993.264.2.E264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel SS, Stark RI, Myers MM, Tropper PJ, Kim YI. Blood pressure and HR in the fetal lamb: relationship to hypoglycemia, hypoxemia and growth restriction. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:R1415–1421. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1996.271.5.R1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derks JB, Giussani DA, Jenkins SL, Wentworth RA, Visser GH, Padbury JF, Nathanielsz PW. A comparative study of cardiovascular, endocrine and behavioural effects of betamethasone and dexamethasone administration to fetal sheep. J Physiol. 1997;499:217–226. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp021922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas-Denton R, Moritz KM, Bertram JF, Wintour EM. Compensatory renal growth after unilateral nephrectomy in the ovine fetus. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:406–410. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V132406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards LJ, McMillen IC. Maternal undernutrition increases arterial blood pressure in the sheep fetus during late gestation. J Physiol. 2001;533:561–570. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0561a.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards LJ, Simonetta G, Owens JA, Robinson JS, McMillen IC. Restriction of placental and fetal growth in sheep alters fetal blood pressure responses to angiotensin II and captopril. J Physiol. 1999;515:897–904. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.897ab.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falardeau P, Martineau A. Prostaglandin I2 and glucocorticoid-induced rise in arterial pressure in the rat. J Hypertens. 1989;7:625–632. doi: 10.1097/00004872-198908000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher AJ, McGarrigle HH, Edwards CM, Fowden AL, Giussani DA. Effects of low dose dexamethasone treatment on basal cardiovascular and endocrine function in fetal sheep during late gestation. J Physiol. 2002;545:649–660. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.015693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forhead AJ, Broughton Pipkin F, Fowden AL. Effect of cortisol on blood pressure and the rennin-angiotensin system in fetal sheep during late gestation. J Physiol. 2000;526:167–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00167.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowden AL, Mijovic J, Silver M. The effects of cortisol on hepatic and renal gluconeogenic enzyme activities in the sheep fetus during late gestation. J Endocrinol. 1993;137:213–222. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1370213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowden AL, Mundy L, Silver M. Developmental regulation of glucogenesis in the sheep fetus during late gestation. J Physiol. 1998;508:937–947. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.937bp.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins P, Steyn C, Ozaki T, Saito T, Noakes DE, Hanson MA. Effect of maternal undernutrition in early gestation on ovine fetal blood pressure and cardiovascular reflexes. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2000;279:R340–348. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.279.1.R340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen EC, Gallaher BW, Breier BH, Harding JE. The effect of a chronic maternal cortisol infusion on the late-gestation fetal sheep. J Endocrinol. 2002;174:27–36. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1740027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornel L, Nelson WA, Manisundaram B, Chigurupati R, Hayashi T. Mechanism of the effects of glucocorticoids and mineralocorticoids on vascular smooth muscle contractility. Steroids. 1993;58:580–587. doi: 10.1016/0039-128x(93)90099-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langlois DA, Matthews SG, Yu M, Yang K. Differential expression of 11 β hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 1 and 2 in the developing ovine fetal liver and kidney. J Endocrinol. 1995;147:405–411. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1470405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Saunders JC, Gilmour RS, Silver M, Fowden AL. Insulin-like growth factor-II messenger ribonucleic acid expression in fetal tissues of the sheep during late gestation: effects of cortisol. Endocrinology. 1993;132:2083–2089. doi: 10.1210/endo.132.5.8477658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llanos AJ, Seron-Ferre M, Ramachandran J, Creasy RK, Heymann MA, Rudolph AM. Cardiovascular responses to alpha-melanocyte stimulating hormone during the perinatal period in sheep. Pediatr Res. 1983;17:903–908. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198311000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lok F, Owens JA, Mundy L, Robinson JS, Owens PC. Insulin-like growth factor I promotes growth selectively in fetal sheep in late gestation. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:R1148–1155. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1996.270.5.R1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombès M, Oblin ME, Gasc JM, Baulieu EE, Farman N, Bonvalet JP. Immunohistochemical and biochemical evidence for a cardiovascular mineralocorticoid receptor. Circ Res. 1992;71:503–510. doi: 10.1161/01.res.71.3.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumbers ER, Bernasconi C, Burrell JH. Effects of infusions of ACTH in the chronically catheterized pregnant ewe and her fetus. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:R445–452. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.274.2.R445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lye SJ, Challis JR. In vivo adrenocorticotropin (1–24)-induced accumulation of cyclic adenosine monophosphate by ovine fetal adrenal cells is inhibited by concomitant infusion of metopirone. Endocrinology. 1984;115:1584–1587. doi: 10.1210/endo-115-4-1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillen IC, Antolovich GC, Mercer JE, Perry RA, Silver M. Proopiomelanocortin messenger mRNA levels are increased in the anterior pituitary after adrenalectomy in late gestation. Neuroendocrinology. 1990;52:297–302. doi: 10.1159/000125601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillen IC, Warnes KE, Adams MB, Robinson JS, Owens JA, Coulter CL. Impact of restriction of placental and fetal growth on expression of 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 and type 2 messenger ribonucleic acid in the liver, kidney, and adrenal of the sheep fetus. Endocrinology. 2000;141:539–543. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.2.7338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh AC, Gibson KJ, Wu J, Owens PC, Owens JA, Lumbers ER. Chronic effect of insulin-like growth factor I on renin synthesis, secretion, and renal function in fetal sheep. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2001;28:R318–326. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2001.281.1.R318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moritz K, Butkus A, Hantzis V, Peers A, Wintour EM, Dodic M. Prolonged low-dose dexamethasone, in early gestation, has no long-term deleterious effect on normal ovine fetuses. Endocrinology. 2002;143:1159–1165. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.4.8747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muto S, Nemoto J, Ohtaka A, Watanabe Y, Yamaki M, Kawakami K, Nagano K, Asano Y. Differential regulation of Na+-K+-ATPase gene expression by corticosteroids in vascular smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:C731–739. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.270.3.C731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirpiris M, Sudhir K, Yeung S, Jennings G, Whitworth JA. Pressor responsiveness in corticosteroid-induced hypertension in humans. Hypertension. 1992;19:567–574. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.19.6.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees DD, Cellek S, Palmer RM, Moncada S. Dexamethasone prevents the induction by endotoxin of a nitric oxide synthase and the associated effects on vascular tone: an insight into endotoxin shock. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990;173:541–547. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)80068-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segar JL, Bedell K, Page WV, Mazursky JE, Nuyt AM, Robillard JE. Effect of cortisol on gene expression of the renin-angiotensin system in fetal sheep. Pediatr Res. 1995;37:741–746. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199506000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segar JL, Van Natta T, Smith OL. Effect of fetal ovine adrenalectomy on sympathetic and baroreflex responses at birth. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Physiol. 2002;283:R460–467. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00056.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda R, Hatakeyama H, Takeda Y, Iki K, Miyamori I, Sheng WP, Yamamoto H, Blair IA. Aldosterone biosynthesis and action in vascular cells. Steroids. 1995;60:120–124. doi: 10.1016/0039-128x(94)00026-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tangalakis K, Lumbers ER, Moritz KM, Towstoless MK, Wintour EM. Effect of cortisol on blood pressure and vascular reactivity in the ovine fetus. Exp Physiol. 1992;77:709–715. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1992.sp003637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unno N, Wong CH, Jenkins SL, Wentworth RA, Ding XY, Li C, Robertson SS, Smotherman WP, Nathanielsz PW. Blood pressure and heart rate in the ovine fetus: ontogenic changes and effects of fetal adrenalectomy. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:H248–256. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.1.H248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker BR, Williams BC. Corticosteroids and vascular tone: mapping the messenger maze. Clin Sci. 1992;82:597–605. doi: 10.1042/cs0820597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehling M, Neylon CB, Fullerton M, Bobik A, Funder JW. Nongenomic effects of aldosterone on intracellular Ca2+ in vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res. 1995;76:973–979. doi: 10.1161/01.res.76.6.973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wintour EM, Dodic M, Johnston H, Moritz K, Peers A. Kidney and urinary tract. In: Roedeck CH, Whittle MJ, editors. Fetal Medicine: Basic Science and Clinical Practice. London: Churchill Livingston; 1999. pp. 155–171. [Google Scholar]