Abstract

Ca2+-dependent conductances were studied in respiratory interneurons in the brainstem-spinal cord preparation of newborn rats. ω-Conotoxin-GVIA attenuated evoked postsynaptic potentials, spontaneous or evoked inspiratory spinal nerve activity and blocked spike afterhyperpolarization. Furthermore, ω-conotoxin-GVIA augmented rhythmic drive potentials of pre-inspiratory and inspiratory neurons and increased respiratory-related spike frequency of pre-inspiratory cells with no effect on inspiratory hyperpolarization. In contrast, ω-agatoxin-IVA depressed drive potentials of pre-inspiratory and inspiratory neurons and attenuated inspiratory hyperpolarization and spike frequency of pre-inspiratory cells. It did not affect spike shape and exerted only minor, non-significant, attenuating effects on spontaneous or evoked nerve bursts or evoked postsynaptic potentials. Nifedipine diminished drive potentials and spike frequency of pre-inspiratory neurons and shortened drive potentials in some cells. ω-Conotoxin-MVIIC attenuated drive potentials and intraburst firing rate of pre-inspiratory neurons and decreased substantially respiratory frequency. Respiratory rhythm disappeared following combined application of ω-conotoxin-GVIA, ω-conotoxin-MVIIC, ω-agatoxin-IVA and nifedipine. Apamin potentiated drive potentials and abolished spike afterhyperpolarization, whereas charybdotoxin and tetraethylammonium prolonged spike duration without effect on shape of drive potentials. The results show that specific sets of voltage-activated L-, N- and P/Q-type Ca2+ channels determine the activity of particular subclasses of neonatal respiratory neurons, whereas SK- and BK-type K+ channels attenuate drive potentials and shorten spikes, respectively, independent of cell type. We hypothesize that modulation of spontaneous activity of pre-inspiratory neurons via N-, L- and P/Q-type Ca2+ channels is important for respiratory rhythm or pattern generation.

Biophysical studies on isolated cells showed the importance of voltage-activated Ca2+ channels for neuronal signalling (Carbone & Lux, 1984; Miller, 1987; Tsien et al. 1988). The synergistic interaction between Ca2+ channel subtypes and thus their functional relevance can be particularly well studied in rhythmically active neuronal systems. One example is the medullary respiratory network mediating the periodic breathing movement (Feldman, 1986; Bianchi et al. 1995). In vivo studies on cats presented evidence that voltage-activated Ca2+ channels are crucial for respiratory rhythm (Richter et al. 1992, 1993; Ramirez et al. 1998) and potentiation of synaptic burst (‘drive’) potentials (Takeda & Haji, 1993). Furthermore, intracellular injection of Ca2+ chelators was found to attenuate spike adaptation during the period of the drive potential (Champagnat & Richter, 1994; Pierrefiche et al. 1994, 1999). The latter reports suggested that such spike adaptation is due to Ca2+-dependent K+ channels that are opened by Ca2+ influx through voltage-activated Ca2+ channels.

In respiratory neurons, organic Ca2+ channel blockers were first used in the brainstem-spinal cord preparation of newborn rats (Onimaru et al. 1996). In this in vitro model for analysis of respiratory network function (Suzue, 1984; Ballanyi et al. 1999), nifedipine-sensitive (L-type) and ω-conotoxin-GVIA-sensitive (N-type) Ca2+ channels (Swandulla et al. 1991) were found in all classes of respiratory neurons (Onimaru et al. 1996). In contrast, ω-agatoxin-IVA-sensitive (P/Q-type) Ca2+ channels (Llinas et al. 1992) were a characteristic feature of pre-inspiratory (Pre-I) and a subpopulation of inspiratory (Insp) neurons (Onimaru et al. 1996). For analysis of Ca2+ channel properties in the latter report and related in vitro studies (Elsen & Ramirez, 1998; Mironov & Richter, 1998; Frermann et al. 1999) either non-physiological solutions were used or specific blockers were not tested. Accordingly, to date, there is very limited information on the relevance of Ca2+ channel subtypes for rhythmic activity of different types of respiratory neurons and respiratory network function.

Here, we analysed for the first time the effects of specific blockers of voltage-activated Ca2+ channels and Ca2+-dependent K+ channels on membrane potential fluctuations in active respiratory neurons that were not otherwise pharmacologically manipulated. We found that each of the blockers exerts characteristic effects on rhythmic neuronal and nerve activity in the brainstem-spinal cord preparation. For example, the amplitude of drive potentials and the frequency of concomitant spike discharge of Pre-I cells were potentiated by ω-conotoxin-GVIA and attenuated by ω-agatoxin-IVA and ω-conotoxin-MVIIC. Nifedipine diminished drive potentials in Pre-I neurons and shortened drive potential duration in a subpopulation of Pre-I and Insp neurons. As further finding, rhythmic neuronal and nerve activity were blocked by combined application of subtype-specific Ca2+ channel blockers. Ca2+-activated K+ channels are functional since apamin potentiated neuronal drive potential amplitude and blocked single spike afterhyperpolarization, whereas tetraethylammonium and charybdotoxin prolonged spike duration. The results show that a cell-type-specific set of voltage-activated Ca2+ channels and Ca2+-dependent K+ channels determines the shape of drive potentials and action potential properties of neonatal respiratory neurons. In particular, modulation of the activity of Pre-I neurons by these conductances may be important for respiratory rhythm and pattern generation.

METHODS

Preparation and solutions

The experiments were performed on brainstem-spinal cord preparations from 0- to 4-day-old Wistar rats. Experimental protocols were approved by the Animal Research Committee of the Showa Medical School, which operates in accordance with Japanese Governmental Law (No. 105). Under deep ether anaesthesia, the brainstem and spinal cord were isolated as reported previously (Suzue, 1984; Onimaru et al. 1988). The brainstem was decerebrated rostrally between the VIth cranial nerve roots and the lower border of the trapezoid body. The brainstem-spinal cord was placed in a perfusion chamber (volume 2 ml) with the ventral side upwards. The tissue was superfused at 25–26°C with a solution containing (mm): 118 NaCl; 3 KCl; 1.5 CaCl2; 1 MgCl2; 25 NaHCO3; 1.2 NaH2PO4 and 30 d-glucose (pH adjusted to 7.4 by gassing with 95 % O2, 5 % CO2). The flow rate was adjusted to 3.0–4.0 ml min−1. Organic Ca2+ channel blockers were taken from stock solutions. ω-Agatoxin-IVA, ω-conotoxin-GVIA and ω-conotoxin-MVIIC (Peptide Institute Inc., Osaka, Japan) as well as the Ca2+-dependent K+ channel blockers apamin and charybdotoxin (Latoxan, Rosans, France) were diluted in distilled water to a stock solution of 0.1 mm and stored at −20°C. The dihydropyridine Ca2+ channel blocker nifedipine (10 mm; Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) was dissolved in ethanol and kept at −20°C. These blockers were added to the standard saline immediately before application. The final concentrations of the specific blockers were 0.2 μmω-agatoxin-IVA, 2 or 3 μmω-conotoxin-GVIA, 2 or 3 μmω-conotoxin-MVIIC, 20 μm nifedipine, 0.4–1 μm apamin and 0.2 μm charybdotoxin. Other drugs, all obtained from Sigma (München, Germany), were added to the superfusion fluid.

Intracellular recording and histological analysis

Inspiratory-related discharge of respiratory motoneurons was recorded extracellularly with suction electrodes applied to proximal ends of cut ventral roots of spinal cervical (C4 or C5) nerves. Whole-cell recordings from respiratory neurons were obtained with the ‘blind’ patch-clamp technique as described previously in detail (Onimaru & Homma, 1992; Smith et al. 1992). In brief, patch pipettes pulled from borosilicate glass capillaries (GC100 TF, Clark Electromedical Instruments, UK) using a vertical puller (PE-2, Narishige, Tokyo, Japan) had inner diameters of 1.2–2.0 μm and DC resistances of 3–8 MΩ after filling with a solution containing (mm): 130 potassium gluconate, 1 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 2 Na2-ATP, 10 EGTA and 10 Hepes; pH adjusted to 7.2–7.3 with 1 n KOH. For histological analysis of the location and morphology of recorded cells, the patch electrode tips were filled with 1 % Lucifer Yellow (Sigma) dissolved in the standard patch pipette solution. The typical recording time (> 20 min) was sufficient to stain small and distal dendrites as well as the axon (Fig. 1; see also Onimaru & Homma, 1992). At the end of the intracellular recording session, the preparations were immediately fixed for > 48 h at 4°C in Lillie solution (10 % formalin in phosphate buffer, pH 7.0). Subsequently, the solution was rinsed with 15 % sucrose-0.1 m phosphate buffer (pH 7.2), and then immersed overnight in the sucrose solution. Transverse 70 μm or 100 μm frozen sections were then cut on a cryostat. Lucifer-Yellow-filled neurons were visualized using a fluorescence microscope (BH-2, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), and camera-lucida drawings were made.

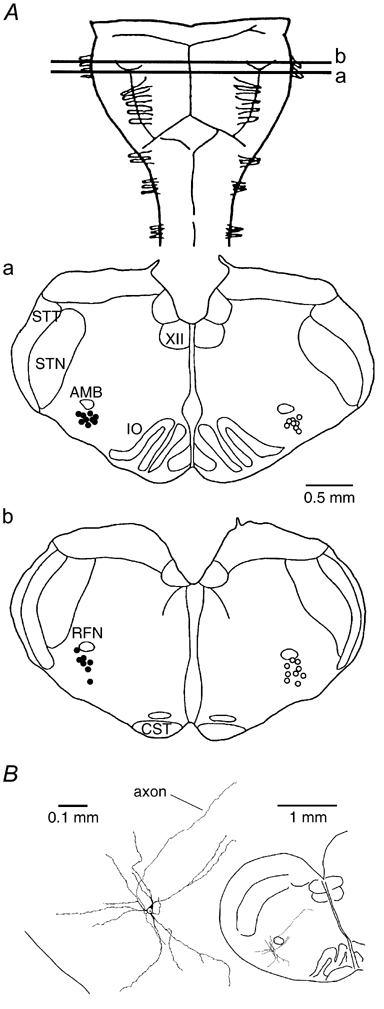

Figure 1. Location of recorded neurons.

A, distribution of recorded neonatal ventral respiratory group (VRG) neurons of the ventrolateral medulla (VLM). Pre-inspiratory (Pre-I, filled circles) and inspiratory (Insp, open circles) VLM-VRG neurons were recorded within ±100 μm distance from the lines (a and b) indicating the rostrocaudal position of cross-sections. Cells are plotted to distinct sides of the medulla for higher clarity. XII, hypoglossal nucleus; STT, spinal trigeminal tract; STN, spinal trigeminal nucleus; AMB, ambigual nucleus; IO, inferior olive; RFN, retrofacial nucleus; CST, corticospinal tract. B, histological analysis of a Lucifer-Yellow-filled cell showed that the soma, most portions of the dendritic tree and the axon were located at a depth > 200 μm from the ventral surface. In this cell it was found that apamin (0.4 μm) abolished the afterhyperpolarization of single spikes within 12 min after the start of superfusion of the drug. A very similar distribution of cell processes and kinetics of drug effects was observed for > 70 % of recorded neurons. (For details, see text.)

Respiratory interneurons were distributed in the ventrolateral medulla including the region of the ventral respiratory group (VLM-VRG) (Arata et al. 1990; Smith et al. 1990; Onimaru et al. 1997; Ballanyi et al. 1999). In the vast majority of cells, the soma and the major portion of the dendrites and axons were located at a depth of 200–500 μm below the ventral surface of the medulla (Fig. 1). The patch electrode was inserted through a small region of the ventral surface of the medulla where the pia was removed with a glass needle. Slight positive pressure (5–15 cmH2O) was applied to keep the tip of the patch electrode clean. When the electrode approached a respiratory neuron, an increase in the voltage response of the patch electrode to injection of negative DC current by up to 150 % was observed. Subsequently, positive pressure was released and negative pressure applied for formation of a gigaohm (> 1 GΩ) seal. Afterwards, the whole-cell configuration was established by gentle suction. In some cases, this was combined with injection of a single-shot hyperpolarizing current pulse (amplitude 0.6–1.0 nA, duration 30 ms). Membrane potential (Vm) was recorded with a single-electrode voltage-clamp amplifier (CEZ-3100; Nihon Koden, Tokyo, Japan). A bridge balance circuit was used for compensation of the access resistance that ranged between 20 and 60 MΩ. Current and voltage signals were recorded using a DAT data recorder (RD-120TE, TEAC, Tokyo, Japan). In one set of experiments, postsynaptic potentials (PSPs) were evoked by electrical stimulation (16–24 V, 100 μs) of the contralateral VLM using tungsten electrodes with 2 MΩ resistance and 30 μm tip diameters.

Only cells were analysed in which a resting Vm of at least −40 mV as well as overshooting (respiration-related) action potentials were revealed immediately after establishing the whole-cell configuration. In a previous study (Onimaru et al. 1996), we determined that liquid junction potentials were < 12 mV using the same low Cl− patch electrode solution as in the present study. In that previous report, no significant change in mean resting Vm of several types of neonatal VRG neurons was revealed using either low or high Cl− electrodes that had liquid junction potentials < 4 mV. Accordingly, Vm recordings were not corrected for liquid junction potentials. Membrane resistance (Rm) was measured at resting Vm (‘input resistance’) or at a holding potential of −50 mV which was close to average resting Vm (Ballanyi et al. 1999) by injection of hyperpolarizing current pulses (amplitude 10–100 pA, duration 0.5–1 s). Vm was recorded from two classes of VLM-VRG cells, namely Insp and Pre-I neurons (Fig. 1). Insp neurons are classified into three subtypes (Onimaru & Homma, 1992; Ballanyi et al. 1999). Type I neurons (Insp-I) show excitatory postsynaptic potentials (EPSPs) prior to onset as well as after termination of inspiratory nerve bursts corresponding to the pre- and post-inspiratory phases of respiratory rhythm (Richter et al. 1992). In type II (Insp-II) cells, EPSPs are revealed only during the inspiratory phase, whereas type III (Insp-III) neurons are hyperpolarized by synchronized inhibitory postsynaptic potentials (IPSPs) during the pre- and post-inspiratory phases. In Pre-I neurons (Fig. 2B), action potential discharge is observed during the pre- and post-inspiratory phases (Onimaru & Homma, 1987, 1992). This type of neonatal respiratory neurons was also classified as biphasic expiratory cells (Smith et al. 1990; Brockhaus & Ballanyi, 1998, 2000).

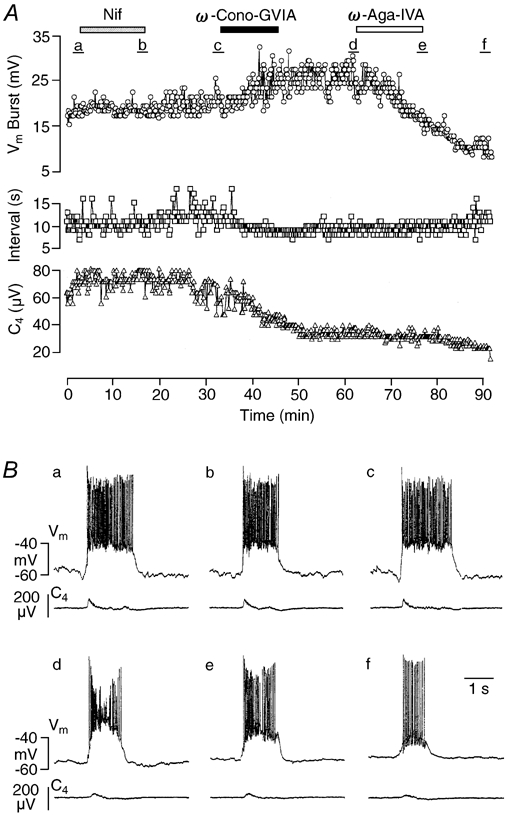

Figure 2. Effects of ω-conotoxin-GVIA (ω-Cono-GVIA) on a Pre-I neuron.

A, time course of changes in the respiratory drive potential amplitude (Vm Burst, circles), burst interval (Interval, squares) of Pre-I neuron activity and amplitude of spinal nerve burst (C4, triangles) induced by ω-Cono-GVIA (2 μm). B, traces of membrane potential (Vm) of the Pre-I neuron and of C4 activity; a and b correspond to a and b in A, respectively. Note that the toxin did not affect inspiratory-related inhibition, whereas the amplitude of the drive potential increased to about 150 % of control. C, potentiating effect of ω-Cono-GVIA on respiratory drive potential amplitude. The recording shows at higher time resolution a single respiratory-related burst indicating how the relative changes in drive potential amplitude and spike frequencies of Table 2 were determined. Left, control close to a in A. Right, during ω-Cono-GVIA close to b in A.

Action of organic channel blockers

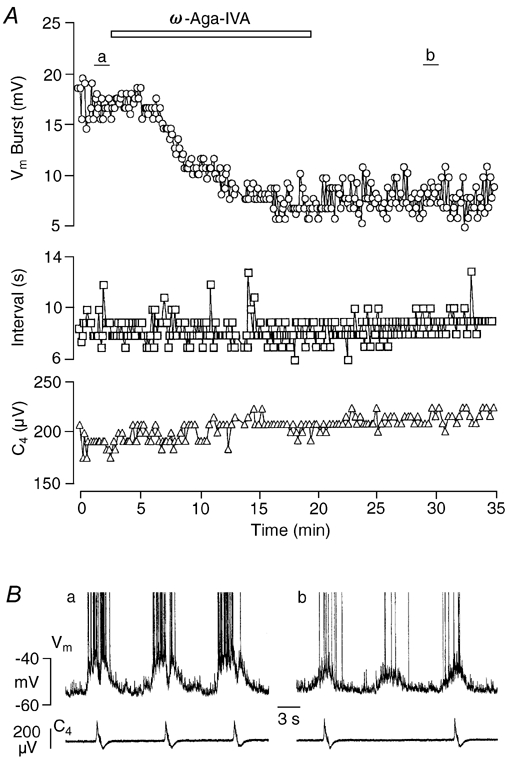

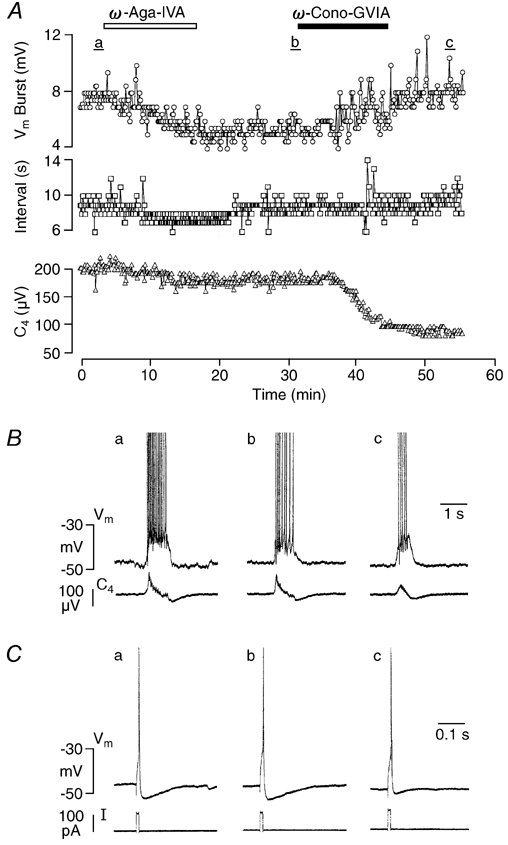

The tissue concentration, in particular that of the high molecular weight toxins (Dunlap et al. 1995), may differ notably from that of the bulk solution at a given time. This is important to note as intracellular recording was carried out at differing tissue depths (Fig. 1). The uncertainty regarding the actual concentration of the drugs at their site of action must be taken into account due to possible cross-sensitivity (Miller, 1987; Dunlap et al. 1995). However, cross-sensitivity of the drugs with different Ca2+ channel subtypes does not appear to be a major problem under the present experimental conditions. We showed previously that the organic blockers exert distinct effects on intrinsic membrane properties of VLM-VRG neurons in the brainstem-spinal cord preparation (Onimaru et al. 1996). For example, nifedipine, but not ω-agatoxin-IVA, abolished Ca2+ spikes mediated by L-type Ca2+ channels. On the contrary, the toxin, but not the dihydropyridine, suppressed depolarizations due to P-type Ca2+ channels. Also in the present study, the drugs had clearly discernable effects on neuronal and nerve bursting (Figs 2–5). The action of the organic blockers used here was slow and almost irreversible (Olivera et al. 1994). Thus, only the effect of the first drug applied to a fresh preparation was analysed. Quantification was carried out when the intracellular effect reached a steady-state, typically within 10–25 min corresponding with the application time of the toxins (Fig. 2 and Fig. 4). In some cases, analysis was carried out after wash-out of the toxins from the bath with the agent still in the tissue and developing its effect, but always before application of a further substance (Fig. 3 and Fig. 5). For assessment of drug effects on spontaneous or evoked action potentials or evoked PSPs, between five and ten consecutive traces were averaged.

Figure 5. Effects of Ca2+ channel blockers on an Insp-III neuron.

A, time course of changes in drive potential amplitude (Vm Burst, circles) as well as burst interval (Interval, squares) of Insp-III neuron activity, and amplitude of spinal nerve burst (C4, triangles) upon consecutive administration of nifedipine (Nif, 20 μm), ω-Cono-GVIA (2 μm) and ω-Aga-IVA (0.2 μm). Augmentation of inspiration-related neuronal drive potential induced by ω-Cono-GVIA was reversed into a decline of the response by ω-Aga-IVA. Note that the C4 amplitude was reduced to about 50 % of control by ω-Cono-GVIA. B, individual oscillations of membrane potential (Vm) of the Insp-III neuron and of C4 activity; a-f correspond to time periods a-f in A, respectively.

Figure 4. Effects of ω-Aga-IVA on a Pre-I neuron.

A, time course of changes in drive potential amplitude (Vm Burst, circles) as well as burst interval (Interval, squares) of Pre-I neuron activity and cervical nerve burst amplitude (C4, triangles) due to ω-Aga-IVA (0.2 μm). Note that burst amplitude was reduced to < 50 % of control. B, traces of membrane potential (Vm) of Pre-I neuron and C4 activity; a and b correspond to time periods a and b in A, respectively. Note in b that attenuation of neuronal activity was accompanied by a failure of nerve discharge.

Figure 3. Effects of ω-agatoxin-IVA (ω-Aga-IVA) and ω-Cono-GVIA on an inspiratory type-III (Insp-III) neuron.

A, time course of changes in drive potential amplitude (Vm Burst, circles) and burst interval (Interval, squares) of neuronal activity and spinal nerve burst amplitude (C4, triangles) upon successive administration of ω-Aga-IVA (0.2 μm) and ω-Cono-GVIA (2 μm). Note that ω-Aga-IVA irreversibly reduced the drive potential amplitude to about 60 % of control, whereas the amplitude of single C4 nerve bursts only decreased slightly. The inspiration-related drive potential of the neuron re-increased upon subsequent addition of ω-Cono-GVIA, but C4 activity declined further to < 50 % of control. B, individual neuronal and nerve bursts at time periods a-c in A. C, action potentials induced by a 10 ms depolarizing current pulse at time periods a-c in A. Note the decrease in spike afterhyperpolarization after ω-Cono-GVIA.

Drug effects were also analysed on the respiratory-related drive potential that results from several processes including excitatory and inhibitory PSPs and, probably also, intrinsic ion conductances such as persistent Na+ channels (Richter et al. 1992; Ballanyi et al. 1999). According to the primary aim of this study, which was to test the effects of specific blockers of Ca2+-dependent conductances on normal rhythmic activity, no attempt was made to pharmacologically manipulate the drive potential. The magnitude of the drive potential was determined as the voltage difference between resting Vm in the interburst phase and the peak of the plateau depolarization during drive potential. The occurrence of spontaneous action potentials at a rate of 5–20 Hz did not substantially hamper this analysis as their frequency was sufficiently low (Fig. 2C). Mean values were calculated from five consecutive drive potentials for control and drug. Blocker effects were also analysed on intraburst spike frequency during five consecutive respiratory cycles. Numbers represent means ±s.d. of mean. Significance values (P < 0.05) were determined with a Student's t test for paired samples.

RESULTS

Effects of specific Ca2+ channel blockers were previously tested primarily on (whole-cell) Ca2+ currents of isolated cells or stimulus-evoked synaptic responses (Carbone & Lux, 1984; Miller, 1987; Tsien et al. 1988; Swandulla et al. 1991; Llinas et al. 1992). The following experiments were performed to illuminate the synergistic action of Ca2+-dependent channels on spontaneous activity within an active neuronal network. In the brainstem-spinal cord preparation from newborn rats, synaptic interactions within the network of medullary respiratory neurons can be studied using intracellular recording techniques. Furthermore, functional consequences of pharmacological manipulations can be assessed in this in vitro model by monitoring inspiration-related motor output of the respiratory network from spinal nerves (Ballanyi et al. 1999).

In this en bloc preparation, we have identified earlier L-, N- and P/Q-type Ca2+ channels using nifedipine, ω-conotoxin-GVIA and ω-agatoxin-IVA, respectively (Onimaru et al. 1996). In that previous study, VLM-VRG neurons were pharmacologically isolated with tetrodotoxin. Furthermore, the neurons were dialysed and superfused with K+ channel blockers to unmask regenerative Ca2+ responses. In the present work, we have tested effects of these Ca2+ channel blockers on spontaneous drive potentials of respiratory neurons and cervical nerve activity. Although T-type Ca2+ channels were identified in respiratory neurons of our previous report (Onimaru et al. 1996), we did not analyse here the functional role of such low voltage-activated Ca2+ channels for the following reasons: (i) these Ca2+ channels are only a feature of < 20 % of respiratory interneurons in neonatal rats, (ii) at resting Vm of VLM-VRG neurons in the brainstem-spinal cord preparation, which is around −50 mV, T-type Ca2+ channels are persistently inactivated (Huguenard, 1996), (iii) there is no specific blocker of T-type Ca2+ channels available yet. Instead, we have used apamin and charybdotoxin to investigate whether Ca2+ influx through Ca2+ channels shapes neuronal bursting by activation of Ca2+-dependent K+ channels (Moczydlowski et al. 1988; Sah, 1996).

Organic Ca2+ channel blockers

Effects of organic Ca2+ channel blockers were tested on inspiratory spinal nerve activity and Vm fluctuations of VLM-VRG neurons. In individual preparations, ω-conotoxin-GVIA (2 μm), ω-agatoxin-IVA (0.2 μm) or nifedipine (20 μm) either decreased, increased or did not change the frequency of cervical (C4-C5) nerve activity (Figs 2–5). The drugs tended to induce a decrease of respiratory rate, but this effect was not significant. In contrast, 2 μmω-conotoxin-MVIIC, which does not discriminate between N- and P/Q-type Ca2+ channels, reduced respiratory frequency (by 39 %) in 10 preparations tested (Table 1). The latter agent, as well as ω-agatoxin-IVA and nifedipine, had no effect on the amplitude of inspiratory-related nerve discharge within the application time of 15–20 min (Table 1), although a progressive amplitude depression was revealed under ω-agatoxin-IVA and ω-conotoxin-MVIIC during recording periods > 90 min. Within several minutes of application of ω-conotoxin-GVIA, the amplitude of single nerve bursts decreased progressively and reached a rather stable level of between 80 and 50 % of control after 20–30 min (Fig. 2 and Fig. 3; Table 1). The amplitude depression of nerve bursting continued with a noticeably slower time course and could reach levels of < 20 % of control after > 1 h.

Table 1.

Effects of organic Ca2+ channel blockers on inspiratory nerve activity

| Rate (% of control) | Amplitude (% of control) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Nifedipine (20 μm; n = 12) | 88.4 ± 29.1 | (+, 2; ±, 3; −, 7) | 103 ± 14.7 |

| ω-Aga-IVA (0.2 μm; n = 10) | 94.8 ± 25.8 | (+, 3; ±, 3; −, 4) | 100 ± 18.0 |

| ω-Cono-GVIA (2 μm; n = 12) | 97.0 ± 22.4 | (+, 2; ±, 4; −, 6) | 69.9 ± 9.0*** |

| ω-Cono-MVIIC (2 μm; n = 10) | 61.0 ± 13.8*** | (+, 0; ±, 0; −, 10) | 91.7 ± 12.4 |

ω-Aga-IVA, ω-agatoxin-IVA; ω-Cono-GVIA, ω-conotoxin-GVIA; ω-Cono-MVIIC, ω-conotoxin-MVIIC; +, increase > 10 %; ±, change < 10 %; −, decrease > 10 %;

P < 0.001; measurements taken 15–20 min after start of exposure.

The organic blockers did not change resting Vm or Rm (Table 2) indicating that voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels are not profoundly active in these cells at resting potential. In both Pre-I and Insp neurons, ω-agatoxin-IVA substantially reduced the amplitude of the respiration-related excitatory drive potential (Figs 3–5; Table 2). This blocking effect was more pronounced in Pre-I and Insp-III cells than in other types of Insp neurons. ω-Agatoxin-IVA reduced the frequency of spiking during the drive potential by > 50 %, whereas such an effect was not revealed for Insp cells (Table 2). ω-Conotoxin-GVIA increased the drive potential amplitude of Pre-I (Fig. 2) and Insp (Fig. 5) neurons and also elevated significantly intraburst spike frequency in Pre-I, but not in Insp cells (Table 2). The kinetics of augmentation of drive potentials evoked by ω-conotoxin-GVIA was paralleled by those of the decrease in the amplitude of the nerve signal (Fig. 2 and Fig. 3). The toxin also caused partial inactivation of drive potential-associated spike discharge in particular in Insp-III neurons (Fig. 5B). Augmentation of drive potentials due to ω-conotoxin-GVIA was also observed after pretreatment with ω-agatoxin-IVA (Fig. 3) and nifedipine (Fig. 5). Similarly, ω-agatoxin-IVA depressed drive potential in cells previously exposed to ω-conotoxin-GVIA (Fig. 5). ω-Conotoxin-MVIIC significantly decreased drive potentials in Pre-I, but not Insp cells (Fig. 6; Table 2) and in both cell types it blocked the afterhyperpolarization of single spike discharge that either occurred spontaneously or was evoked by a short depolarizing current pulse. A similar blocking effect on spike afterhyperpolarization was revealed upon administration of ω-conotoxin-GVIA to Pre-I (n = 2) or Insp (n = 3) neurons (Fig. 3C), whereas the other Ca2+ channels blockers had no effect.

Table 2.

Effects of organic Ca2+ channel blockers on membrane properties

| Intraburst firing | Drive potential amplitude | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vm(mV) | Rm (MΩ) | freuqency(Hz) | amplitude (% of control) | |

| Inspiratory neurons | ||||

| Nifedipine (20 μm; n = 8) | ||||

| Control | −51.0 ± 5.5 | 469 ± 175 | 18.1 ± 9.1 | — |

| Drug | −50.3 ± 6.5 | 458 ± 159 | 18.8 ± 8.4 | 110 ± 13.9 |

| ω-Aga-IVA (0.2 μm; n = 5) | ||||

| Control | −49.1 ± 5.1 | 466 ± 134 | 20.7 ± 7.5 | — |

| Drug | −48.8 ± 5.8 | 441 ± 141 | 17.1 ± 7.2 | 78.2 ± 14.3* |

| ω-Cono-GVIA (2 μm; n = 6) | ||||

| Control | 48.3 ± 5.0 | 368 ± 112 | 20.7 ± 5.8 | — |

| Drug | −48.3 ± 4.9 | 368 ± 94.7 | 21.6 ± 6.3 | 127 ± 22.3* |

| ω-Cono-MVIIC (2 μm; n = 5) | ||||

| Control | 53.0 ± 1.4 | 326 ± 195 | 19.8 ± 7.6 | — |

| Drug | −52.8 ± 3.1 | 286 ± 131 | 17.2 ± 11.1 | 94.3 ± 17.6 |

| Pre-inspiratory neurons | ||||

| Nifedipine (20 μm; n = 5) | ||||

| Control | −45.4 ± 2.1 | 450 ± 133 | 14.2 ± 4.7 | — |

| Drug | −43.6 ± 3.0 | 412 ± 111 | 9.3 ± 4.4* | 63.0 ± 37.3* |

| ω-Aga-IVA (0.2 μm; n = 5) | ||||

| Control | −46.8 ± 5.4 | 424 ± 170 | 14.5 ± 2.8 | — |

| Drug | 45.8 ± 4.7 | 384 ± 182 | 6.8 ± 4.0** | 57.8 ± 15.8** |

| ω-Cono-GVIA (2 μm; n = 5) | ||||

| Control | 50.4 ± 5.1 | 460 ± 70.1 | 8.9 ± 3.1 | — |

| Drug | −50.2 ± 6.8 | 447 ± 63.6 | 14.4 ± 5.6* | 151 ± 36.6* |

| ω-Cono-MVIIC (2 μm; n = 5) | ||||

| Control | −47.6 ± 2.6 | 578 ± 65 | 10.7 ± 5.4 | — |

| Drug | −46.6 ± 2.4 | 677 ± 107 | 7.4 ± 5.4* | 73.5 ± 21.9** |

Vm, membrane potential; Rm, membrane resistance

P < 0.05

P < 0.01; measurements taken 15–20 min after start of exposure.

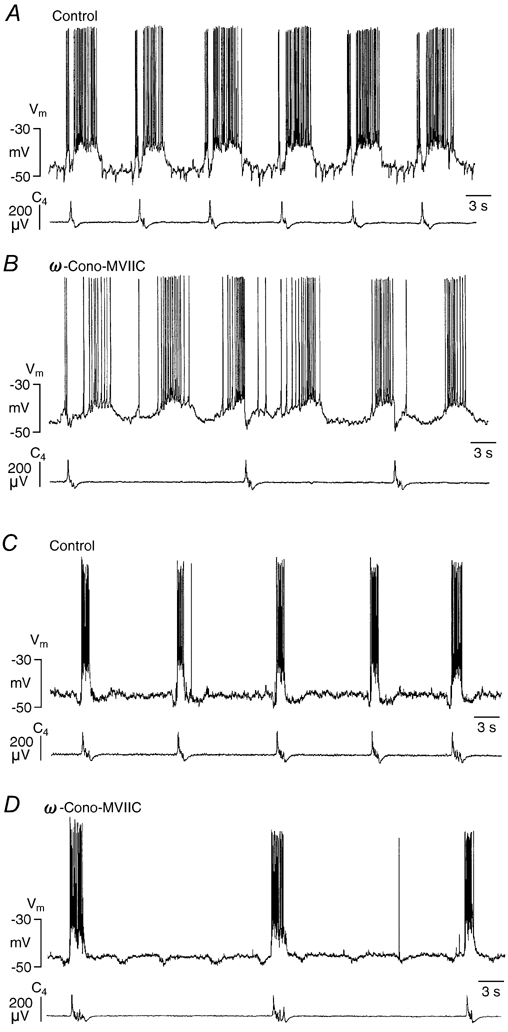

Figure 6. Effects of ω-Cono-MVIIC on respiratory neurons.

A and B, effects on a Pre-I neuron. A, control. B, 16 min after start of exposure to 2 μmω-Cono-MVIIC. Bath-application of the agent resulted in a substantial decrease of respiratory frequency that was not accompanied by a decrease in burst frequency of the Pre-I cell. Note that ω-Cono-MVIIC reduced drive potential amplitude. C and D, effects on an Insp-III neuron. C, control. D, 15 min after start of exposure to 2 μmω-Cono-MVIIC. The drug depressed the frequency of rhythmic activity in the same way as it slowed inspiratory nerve activity. Note that the pre- and post-inspiratory hyperpolarizations due to activity of presynaptic Pre-I cells were uncoupled from inspiratory activity.

Nifedipine significantly reduced both drive potential amplitude and spike frequency of Pre-I neurons, whereas no effect was revealed in Insp neurons (Fig. 5; Table 2). The dihydropyridine also attenuated drive potential duration in a subpopulation of Pre-I and Insp cells (Fig. 5B). In three of five preparations, nifedipine induced a moderate uncoupling of rhythmic Pre-I neuron activity and cervical nerve discharge. This indicates that failures of nerve discharge occurred, whereas the regularity of rhythmic activity of Pre-I neurons was not affected. Similar effects were revealed in two of five preparations in response to ω-agatoxin-IVA (Fig. 4B), one of five preparations to ω-conotoxin-GVIA and five of five preparations to ω-conotoxin-MVIIC (Fig. 6). In all preparations in which such uncoupling occurred, it was associated with a decrease in respiratory frequency by > 30 %.

GABAA and/or glycine receptor-mediated respiration-related hyperpolarization (and concomitant suppression of spike discharge) is characteristic for Insp-III and most Pre-I neurons (Onimaru & Homma, 1992). In four Pre-I neurons, inspiratory-related hyperpolarization was not significantly influenced by ω-conotoxin-GVIA (Fig. 2B), but it decreased significantly in seven different Pre-I cells by 51 ± 29 % (P < 0.01) upon exposure to ω-agatoxin-IVA (Fig. 4B). In Insp-III neurons recorded in the present study, hyperpolarizations during the pre- and post-inspiratory phases were not very pronounced and also varied between individual respiratory cycles. Thus, effects of the blockers on respiratory-related IPSPs were not analysed in these cells.

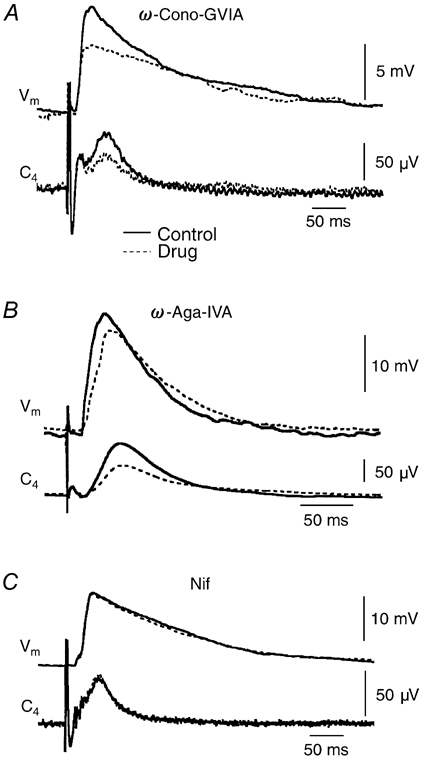

The action of Ca2+ channel blockers on synaptic transmission was tested by electrical stimulation of the contralateral VLM, activating a short-latency reflex-type cervical nerve burst and a concomitant train of polysynaptic EPSPs in the VLM-VRG (Pre-I or Insp) neurons (Onimaru et al. 1988). In six neurons, ω-conotoxin-GVIA significantly (P < 0.01) reduced the amplitude of both EPSPs and cervical nerve reflex (Fig. 7; Table 3). Also ω-agatoxin-IVA (n = 6) tended to depress evoked EPSPs and nerve bursts although the effect was not significant (Fig. 7; Table 3). Nifedipine (n = 5) affected neither EPSPs nor nerve bursts (Fig. 7; Table 3).

Figure 7. Effects of Ca2+ channel blockers on postsynaptic potentials (PSPs) and nerve activity evoked by electrical stimulation of the contralateral ventrolateral medulla.

Vm, membrane potential, C4, spinal nerve reflex. Continuous line, control responses before drug application; dashed line, responses 20–30 min after start of drug application. A, effect of ω-Cono-GVIA (2 μm) on an Insp-III neuron. B, effect of ω-Aga-IVA (0.2 μm) on an Insp-I neuron. C, effect of Nif (20 μm) on an Insp-I neuron. Each trace represents average of 10 (A) or 6 (B and C) sweeps.

Table 3.

Effects of Ca2+ channel blockers on evoked EPSPs and nerve burst

| Control | Drug | |

|---|---|---|

| 2 μmω-conotoxin (n = 6) | ||

| EPSP (mV) | 10.5 ± 4.7 | 7.8 ± 3.8** |

| C4 (μV) | 47.6 ± 42.1 | 36.9 ± 42.8* |

| 0.2 μmω-agatoxin (n = 6) | ||

| EPSP (mV) | 9.2 ± 3.4 | 7.9 ± 1.6 |

| C4 (μV) | 81.9 ± 94.2 | 62.6 ± 46.2 |

| 20 μm nifedipine (n = 5) | ||

| EPSP (mV) | 12.3 ± 4.5 | 15.4 ± 6.4 |

| C4 (mV) | 70.0 ± 45.3 | 95.6 ± 59.6 |

P < 0.05;

P < 0.01; measurements taken 15–20 min after exposure.

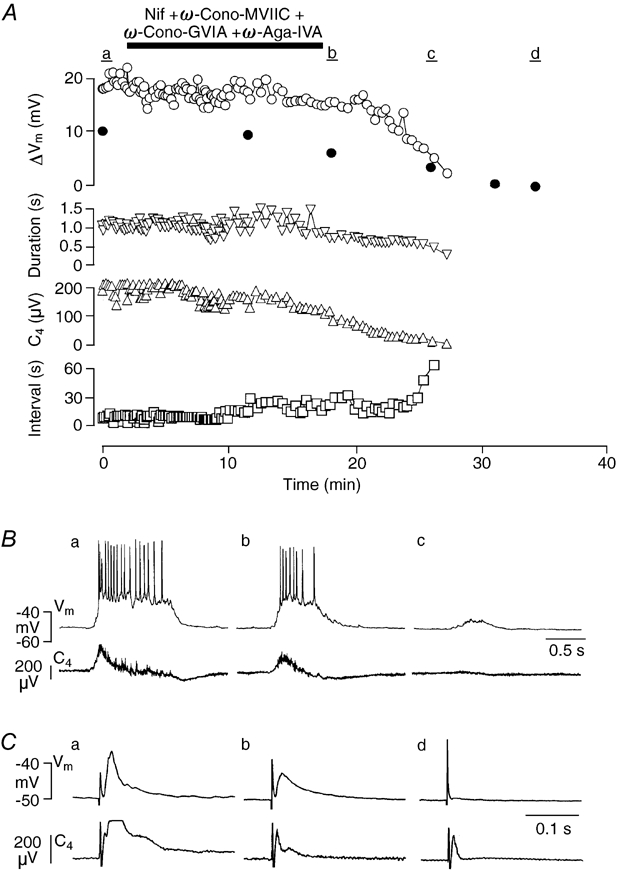

As the specific blockers alone did not abolish medullary respiratory activity, a solution was applied that contained ω-agatoxin-IVA (0.2 μm), ω-conotoxin-GVIA (3 μm), nifedipine (20 μm) and the N- and P/Q-type Ca2+ channel blocker ω-conotoxin-MVIIC (3 μm). Within 6–8 min of application, a transient increase in inspiratory burst rate by 141.1 ± 21.4 % (n = 5; P < 0.01) was observed. This acceleration of respiratory rhythm turned into a frequency decrease that stabilized at 42.7 ± 11.7 % (P < 0.01) of control after 14–15 min (Fig. 8). Both the amplitude and duration of spontaneous drive potentials and evoked EPSPs of Insp neurons (n = 5), as well as of evoked and inspiratory-related spinal nerve bursts, gradually decreased even after wash-out of the drugs from the recording chamber. Neuronal and nerve activities were abolished within 25–40 min after onset of toxin administration (Fig. 8). In line with our previous results using Co2+ (Ballanyi et al. 1999), addition of the nonspecific Ca2+ channel blocker Cd2+ (100 μm) abolished cellular and nerve respiratory activity within < 5 min (not shown).

Figure 8. Effects of cocktail application of Ca2+ channel blockers on bursting in an Insp-II neuron.

A, time course of changes in the drive potential amplitude (ΔVm, open circles), burst duration (Duration, downward triangles) as well as burst interval (Interval, squares) of Insp-II neuron activity and amplitude of spinal nerve burst (C4, upward triangles) upon simultaneous administration of Nif (20 μm), ω-Cono-GVIA (3 μm), ω-Cono-MVIIC (3 μm) and ω-Aga (0.2 μm). Amplitude of evoked EPSPs (ΔVm) by stimulation of the contralateral vetrolateral medulla is also plotted (filled circles). Inspiration-related neuronal drive potential amplitude, burst duration and C4 nerve burst amplitude irreversibly decreased, whereas the burst interval increased even after wash out. B, traces of membrane potential (Vm) of the Insp-II neuron and C4 activity that correspond to time periods a-c in A, respectively. C, evoked EPSPs (average of 5 traces) of the Insp-II neuron and C4 activity that correspond to time periods a-c in A, respectively.

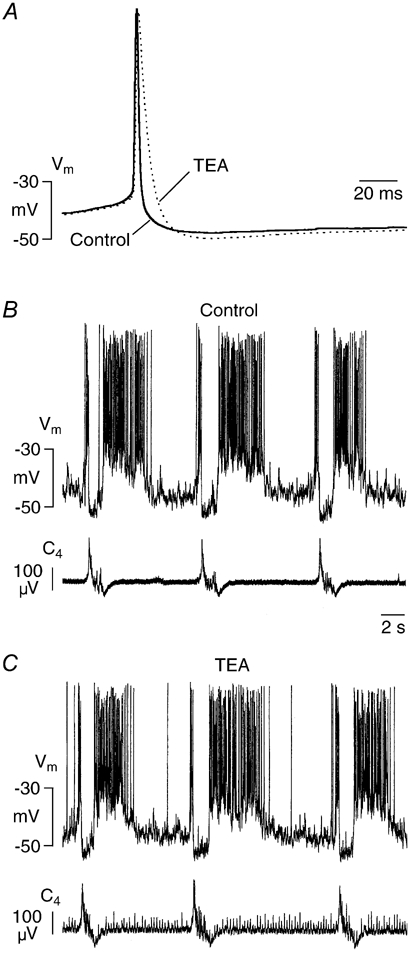

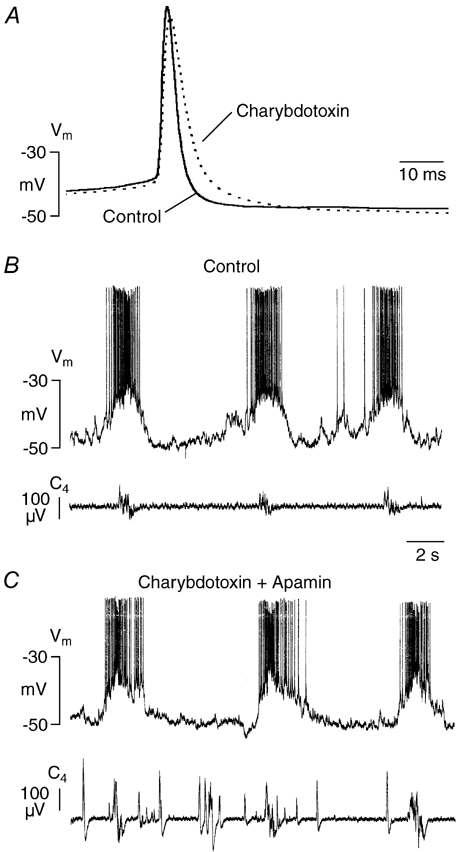

Blockers of Ca2+-activated K+ channels

The observation that ω-conotoxin-GVIA potentiates drive potentials and blocks spike afterhyperpolarization suggested that Ca2+ influx through voltage-activated Ca2+ channels activates Ca2+-dependent K+ channels. To test for this assumption, effects of the BK-type Ca2+-activated K+ channel blocker charybdotoxin and the SK-type Ca2+-activated K+ channel blocker apamin (Moczydlowski et al. 1988; Sah, 1996) were examined. Also tetraethylammonium (TEA) was used; this is a rather nonspecific K+ channel blocker, but it abolishes BK-type Ca2+-activated K+ channels at low millimolar concentrations without major effects on other K+ channels (Sah, 1996; Pedarzani et al. 2000).

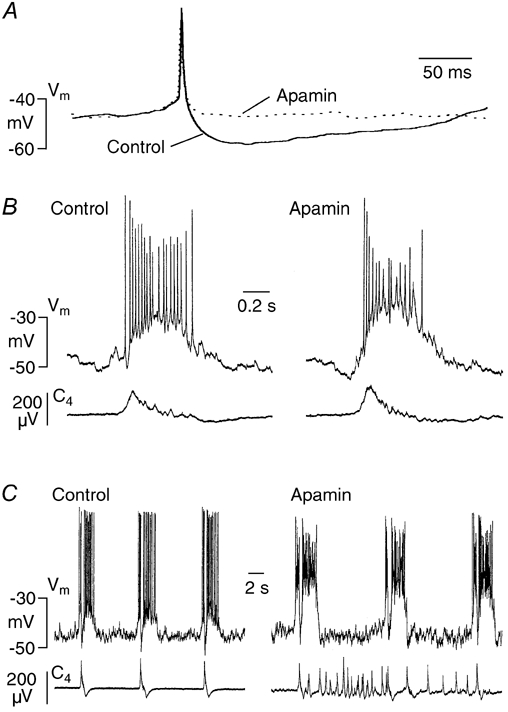

Apamin (0.4–1 μm) had no effect on resting Vm or Rm, but it irreversibly depressed afterhyperpolarization following evoked (n = 5) or spontaneous (n = 4) action potentials (Fig. 9A). The bee venom furthermore augmented drive potential in 8 of 11 neurons, namely six Insp (Fig. 9B) and five Pre-I cells (Fig. 9C). The mean increase in drive potential amplitude after 6–10 min of apamin treatment was 171 ± 74 % (n = 11; P < 0.05) of control. In particular in Insp-III cells, Na+ spikes during the activity phase were partially inactivated following exposure to apamin (n = 5; Fig. 9B) as was also revealed with ω-conotoxin-GVIA (Fig. 5B). Apamin had no effect on the duration of individual neuronal or nerve bursts, but had a tendency to reduce respiratory frequency: 0.4 μm of the drug decreased the frequency from 7.3 ± 1.0 to 6.6 ± 1.4 bursts min−1 (n = 8; not significant), whereas 1 μm apamin reduced the frequency from 7.9 ± 1.2 to 6.2 ± 1.5 bursts min−1 (n = 6; not significant). Furthermore, the toxin induced non-respiratory nerve discharge that stabilized after > 10 min of exposure. This non-respiratory nerve activity could mask inspiratory-related nerve bursting, but it was not revealed in the intracellular recordings (Fig. 9C). The apamin-induced non-respiratory activity was suppressed by 0.5 mm adenosine (n = 3) that was previously shown to antagonize seizure-like spinal nerve activity in the brainstem-spinal cord preparation (Brockhaus & Ballanyi, 2000). In three further preparations, pre-incubation with adenosine inhibited development of tonic nerve activity under apamin without effect on respiratory neuronal or nerve discharge (not shown).

Figure 9. Effects of apamin on burst activity and spike afterhyperpolarization.

A, in a Pre-I neuron, apamin (4 μm) irreversibly suppressed afterhyperpolarization of a spontaneous single action potential after 5 min. Each trace represents the mean of 4 sweeps. B, in an Insp-III cell, apamin (0.4 μm) potentiated inspiratory-related drive potential after 8 min, whereas pre- and post-inspiratory hyperpolarizations were not profoundly affected. C, in a Pre-I neuron, potentiation of respiratory-related drive potential seen 8 min after application of apamin (1 μm) was associated with inactivation of spike discharge. In contrast, apamin had no major effect on inspiratory-related hyperpolarization and spike inhibition. Note that regular bursting of both neurons was not perturbed by the bee venom despite occurrence of massive irregular nerve (C4) bursting.

In contrast to apamin, bath-application of TEA (1 mm) did not affect spike afterhyperpolarization in five Pre-I neurons and three Insp cells, but it increased spike duration from 2.7 ± 0.4 to 5.2 ± 0.9 ms (n = 8; P < 0.001; Fig. 10). TEA had no effect on duration of individual neuronal or nerve bursts. The agent also induced a moderate, but significant (P < 0.05) decrease of respiratory frequency from 5.8 ± 0.7 to 5.1 ± 1.1 bursts min−1. During the first 2–5 min of administration of TEA, non-respiratory tonic nerve activity developed that was not reflected by increased intracellular activity (Fig. 10C). Exposure of nine neurons to charybdotoxin (0.2 μm) for 20–30 min had no effect on spike afterhyperpolarization, but it significantly increased spike duration from 2.6 ± 0.5 to 3.3 ± 1.1 ms (P < 0.05; Fig. 11A). In four different preparations, even combined application of apamin and charybdotoxin did not cause a major change in the frequency or duration of neuronal (two Pre-I neurons, two Insp cells) drive potentials despite occurrence of profound non-respiratory spinal nerve discharge that was not revealed during the intracellular recordings (Fig. 11B and C). This additional non-respiratory nerve activity was abolished by adenosine (n = 3). In two of the latter four cells, apamin did not profoundly potentiate the drive potential (Fig. 11C).

Figure 10. Effects of tetraethylammonium (TEA) on individual spikes and burst activity.

A, in a Pre-I neuron TEA (1 mm) increased duration of single spontaneous action potentials by > 50 %. Each trace represents average of 7 sweeps. B and C, TEA (1 mm) did not change membrane potential (Vm) fluctuations of a Pre-I neuron within 15 min of administration despite occurrence of tonic activity in spinal nerve recording (C4).

Figure 11. Effects of charybdotoxin on spikes and burst activity.

A, in an Insp-II cell, charybdotoxin (0.2 μm) increased duration of spontaneous spikes by ≈50 % after 30 min of exposure. Each trace represents the mean of 6 sweeps. B and C, in a Pre-I neuron, combined administration of charybdotoxin (0.2 μm, 30 min preincubation) and apamin (0.5 μm, 15 min preincubation) did not perturb rhythmic bursting despite massive disturbance of spinal nerve (C4) discharge. Note that this cell did not respond with an increased burst potential to apamin (for details, see text).

DISCUSSION

Here, we tested for the first time effects of selective organic blockers of Ca2+-dependent conductances on rhythmic cellular activity of different types of medullary respiratory neurons. Each blocker exerted specific effects on subclasses of VLM-VRG neurons in the brainstem-spinal cord preparation that is an established model for analysis of respiratory functions (Suzue, 1984; Smith et al. 1991; Onimaru et al. 1997; Ballanyi et al. 1999).

Shaping of neuronal drive potentials by Ca2+-dependent conductances

The P/Q-type Ca2+ channel blocker ω-agatoxin-IVA attenuated drive potentials, while the N-type Ca2+ channel blocker ω-conotoxin-GVIA had a potentiating effect. Furthermore, ω-conotoxin-GVIA reversed the depressing action of ω-agatoxin-IVA on drive potential amplitude and vice versa. As the effects were irreversible, the toxins appear to act indeed on different Ca2+ channel subtypes and subcellular sites on VLM-VRG neurons. Interestingly, combined block of N- and P/Q-type Ca2+ channels depressed drive potentials in Pre-I neurons with no effect on Insp cells. Upon blocking synaptic transmission using tetrodotoxin, we have shown earlier that P/Q-type Ca2+ channels mediate intrinsic ‘intermediate-voltage’ depolarizations in neonatal VLM-VRG neurons (Onimaru et al. 1996). Accordingly, ω-agatoxin-IVA may act primarily postsynaptically on drive potentials as also indicated by lack of a significant effect of the agent on evoked PSPs. In contrast, the inhibitory effect on spontaneous inspiratory-related IPSPs of Pre-I neurons is most probably due to a presynaptic action since the agent attenuated drive potentials of Insp neurons mediating these IPSPs. Principally, reduction of drive potential amplitude by ω-agatoxin-IVA could also include a presynaptic inhibition of excitatory inputs to these cells via pathways different to those activated by stimulation of the contralateral medulla to evoke PSPs.

As ω-conotoxin-GVIA noticeably reduced stimulus-induced PSPs, it is possible that potentiation of drive potentials by the toxin is caused by presynaptic suppression of hyperpolarizing inputs to VLM-VRG neurons. Some inhibitory synapses appear to be more sensitive to Ca2+ channel blockers than excitatory synapses (Horne & Kemp, 1991; Dunlap et al. 1995). However, block of GABA or glycine receptors does not potentiate drive potentials in neonatal VLM-VRG cells (Brockhaus & Ballanyi, 1998, 2000). Also the finding that inspiratory-related inhibition of Pre-I neurons was not changed by ω-conotoxin-GVIA argues against disinhibition as the cause of potentiation of drive potentials. A more likely explanation for the augmentation of drive potential amplitude is an indirect effect of ω-conotoxin-GVIA on Ca2+-activated K+ channels that are often closely associated with N-type Ca2+ channels (Miller, 1987; Tsien et al. 1988). Accordingly, ω-conotoxin-GVIA-evoked depression of Ca2+ influx would fail to substantially activate Ca2+-activated K+ channels that may normally dampen drive potential. Such a scenario was previously hypothesized for respiratory neurons in adult cats in vivo on the basis of indirect findings using injection of Ca2+ chelators or administration of unspecific blockers (Richter et al. 1993; Champagnat & Richter, 1994; Pierrefiche et al. 1994, 1999).

In the present study, the potentiating effect of apamin showed that SK-type Ca2+-activated K+ channels mediate depression of drive potentials. In line with assumptions on a linked action of N-type Ca2+ channels and SK-type Ca2+-activated K+ channels in VLM-VRG neurons in vitro, both ω-conotoxin-GVIA and apamin blocked single spike afterhyperpolarization, whereas ω-agatoxin-IVA and nifedipine had no such effect. The lack of effect of TEA and charybdotoxin suggests that BK-type Ca2+-activated K+ channels play no major role in shaping drive potentials.

Similar to ω-agatoxin-IVA, nifedipine attenuated the amplitude of drive potentials and also decreased their duration in a subpopulation of cells. This indicates that postsynaptic L-type Ca2+ channels are capable of boosting bursting in respiratory neurons. Interestingly, attenuation of the amplitude of drive potentials was solely observed in Pre-I neurons. This is surprising considering that L-type Ca2+ channels were previously found in various types of VLM-VRG neurons in rats (Onimaru et al. 1996) and other species (Elsen & Ramirez, 1998; Mironov & Richter, 1998; Pierrefiche et al. 1999). Despite lack of a depressing action of nifedipine on evoked PSPs, the boosting effect of L-type Ca2+ channels may be mediated by synaptic pathways independent of those activated by stimulation of the contralateral VLM.

Relevance of Ca2+-dependent conductances for rhythm generation

Nifedipine neither impaired rhythmic network activity nor evoked PSPs. This supports the view that synaptic transmission within the respiratory network is mediated by P/Q-and N-type rather than L-type Ca2+ channels (Llinas et al. 1992; Zhang et al. 1993; Olivera et al. 1994; Dunlap et al. 1995). But ω-conotoxin-GVIA or ω-agatoxin-IVA alone also did not abolish respiratory rhythm over a time course of > 1 h when the specific intracellular effects were already at a steady-state. For explanation, N- and P/Q-type channels may cooperate at synapses of rhythmogenic respiratory neurons to provide a safety mechanism (Olivera et al. 1994; Dunlap et al. 1995; Wu et al. 1998). In line with this view, the N-type plus P/Q-type Ca2+ channel blocker ω-conotoxin-MVIIC substantially decreased respiratory frequency. The observation that the agent did not fully suppress respiratory rhythm may be explained by previous findings that even complete binding of such peptide toxin blockers to the channel does not completely block the Ca2+ current (Olivera et al. 1994). As an alternative explanation, toxin-insensitive R-type Ca2+ channels may also play a role in transmission at synapses relevant for rhythm generation as previously shown for other central nervous synapses (Wu et al. 1998). However, combined application of N-, P/Q- and L-type Ca2+ channel blockers abolished respiratory activity. This may indicate that suppression of drive potentials by nifedipine is necessary to turn slowing of respiratory rhythm due to block of N-type and P/Q-type channels into arrest of respiratory activity. But, it is also possible that nifedipine-sensitive L-type Ca2+ channels contribute to a safety mechanism at rhythmogenic synapses.

The increase in the amplitude of drive potentials of respiratory neurons induced by ω-conotoxin-GVIA was paralleled by a decrease in the amplitude of the respiratory nerve signal. This indicates that synaptic transmission from medullary interneurons to bulbospinal premotor and/or spinal motoneurons is more dependent of N-type Ca2+ channels than synaptic interaction between rhythmogenic VLM-VRG neurons. The lack of depressing effects of combined application of apamin and charybdotoxin on respiratory nerve activity, and the magnitude or duration of drive potentials of VLM-VRG interneurons, supports previous assumptions that Ca2+-activated K+ channels are not critical for rhythm generation or termination of respiratory bursts (Smith et al. 1995; Ballanyi et al. 1999; Butera et al. 1999; Del Negro et al. 2001).

It is not clear at present whether diffusion of the high molecular weight toxins into the tissue was sufficient to affect all rhythmogenic VLM-VRG cells. However, diffusion was apparently not hampered substantially as, for example, the specific blocking effects of apamin and charybdotoxin on spike afterhyperpolarization and duration, respectively, reached steady-state within < 30 min. Our histological analysis revealed that the somata and the majority of the dendrites of most recorded cells were located noticeably deeper than 200 μm within the brainstem tissue. Also, diffusion is not likely to be impeded for the low molecular weight agent TEA, which evoked the same prolongation of spike duration as charybdotoxin. Nevertheless, there is recent evidence that respiratory rhythm is dependent on BK channels after block of glycinergic inhibition (Richter & Spyer, 2001). ω-Conotoxin-GVIA injection into the rhythmogenic pre-Bötzinger Complex (Smith et al. 1991; Gray et al. 1999) of cats abolished respiratory rhythm in vivo (Ramirez et al. 1998). It remains to be elucidated whether this discrepancy with our findings is due to developmental changes in the distribution and/or relevance of Ca2+ channel subtypes (Lorenzon & Foehring, 1995; Magnelli et al. 1998). For an alternative explanation, the absence of afferent inputs may decrease the sensitivity to the toxin of rhythmogenic respiratory structures in the brainstem-spinal cord (Smith et al. 1990; Ballanyi et al. 1999; Richter & Spyer, 2001).

Role of Ca2+-dependent conductances for respiratory network function

Independent of cell types, apamin blocked spike afterhyperpolarization and augmented drive potentials, while charybdotoxin and TEA prolonged spike duration. This shows that SK- and BK-type Ca2+-dependent K+ channels are functional in the respiratory network as hypothesized previously (Champagnat & Richter, 1994; Pierrefiche et al. 1994, 1999; Richter & Spyer, 2001; Tonkovic-Capin et al. 2001). In particular in Insp-III cells, potentiation of drive potentials by apamin led to partial inactivation of Na+ spikes. This indicates that SK-type Ca2+-activated K+ channels counteract excessive depolarization that would impede information transfer from this subclass of respiratory neurons to other cells within the respiratory network (Kashiwagi et al. 1993). Our observation that apamin, charybdotoxin and TEA induced non-respiratory spinal nerve activity may indicate that Ca2+-activated K+ channels exert a stabilizing action on respiratory rhythm. However, these nerve bursts do not seem to originate within the rhythm-generating medullary respiratory network as intracellular recording from VLM-VRG interneurons in the present study did not show non-respiratory bursting in the presence of the blockers. Rather, the sensitivity of such activity to adenosine suggests that it is generated within spinal neuronal networks as previously demonstrated for seizures in the brainstem-spinal cord preparation due to block of Cl−-mediated inhibition (Brockhaus & Ballanyi, 2000).

As one major finding of our study, it was revealed exclusively in Pre-I neurons that ω-conotoxin-GVIA-induced augmentation of drive potentials increased intraburst spike frequency by > 50 %, whereas attenuation of drive potentials by either nifedipine or ω-agatoxin-IVA caused spike frequency to fall to < 60 % of control. This shows that N-type, P/Q-type as well as L-type voltage-activated Ca2+ channels have a strong modulatory action not only on the shape of the drive potential, but also particularly on output activity of this subclass of respiratory interneurons. It was demonstrated recently that Pre-I cells project to the nucleus retroambiguus of the contralateral medulla to bulbospinal neurons that innervate motoneurons to respiratory muscles within the lumbar spinal cord (Janczewski et al. 2002). Accordingly, Pre-I neurons are involved in generation of output pattern of the respiratory network. Furthermore, a Pre-I neuronal network in the rostral ventrolateral medulla appears to constitute a rhythm-generating centre (Onimaru & Homma, 1987) that cooperates with the pre-Bötzinger Complex to generate eupnoeic breathing (Ballanyi et al. 1999; Janczewski et al. 2002). In that regard it was reported recently that opioid-induced depression of respiratory frequency in the brainstem-spinal cord preparation may be due to transmission failure from the Pre-I network to the pre-Bötzinger Complex (Mellen et al. 2003).

A similar effect was exerted by the specific Ca2+ channel blockers, but not by the blockers of Ca2+-dependent K+ channels. Upon combined block of N- and P/Q-type Ca2+ channels using ω-conotoxin-MVIIC, such uncoupling resulted in a major decrease of respiratory frequency. It remains to be elucidated the extent to which modulation of drive potential amplitude, and thus spike frequency, of Pre-I neurons by the Ca2+ channel blockers affects the strength of pre- and post-inspiratory motor output of lumbar rootlets, and thus the activity of abdominal respiratory muscles.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research (AHFMR), and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture in Japan.

REFERENCES

- Arata A, Onimaru H, Homma I. Respiration-related neurons in the ventral medulla of newborn rats in vitro. Brain Res Bull. 1990;24:599–604. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(90)90165-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballanyi K, Onimaru H, Homma I. Respiratory network function in the isolated brainstem-spinal cord of newborn rats. Prog Neurobiol. 1999;59:583–634. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(99)00009-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi AL, Denavit-Saubie M, Champagnat J. Central control of breathing in mammals: neuronal circuitry, membrane properties, and neurotransmitters. Physiol Rev. 1995;75:1–45. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1995.75.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockhaus J, Ballanyi K. Synaptic inhibition in the isolated respiratory network of neonatal rats. Eur J Neurosci. 1998;10:3823–3839. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockhaus J, Ballanyi K. Anticonvulsant A1 receptor-mediated adenosine action on neuronal networks in the brainstem-spinal cord of newborn rats. Neuroscience. 2000;96:359–371. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00544-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butera RJ, Jr, Rinzel J, Smith JC. Models of respiratory rhythm generation in the pre-Botzinger complex. I. Bursting pacemaker neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1999;82:382–397. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.1.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbone E, Lux HD. A low voltage-activated, fully inactivating Ca channel in vertebrate sensory neurons. Nature. 1984;310:501–502. doi: 10.1038/310501a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champagnat J, Richter DW. The roles of K+ conductance in expiratory pattern generation in anaesthetized cats. J Physiol. 1994;479:127–138. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Negro CA, Johnson SM, Butera RJ, Smith JC. Models of respiratory rhythm generation in the pre-Bötzinger Complex. III. Experimental test of model predictions. J Neurophysiol. 2001;86:59–74. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.86.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap K, Luebke JI, Turner TJ. Exocytotic Ca2+ channels in mammalian central neurons. Trends Neurosci. 1995;18:89–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsen FP, Ramirez JM. Calcium currents of rhythmic neurons recorded in the isolated respiratory network of neonatal mice. J Neurosci. 1998;18:10652–10662. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-24-10652.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman JL. Neurophysiology of breathing in mammals. In: Bloom FE, editor. Handbook of Physiology. IV. Bethesda, MD, USA: Blackwell Science Inc; 1986. pp. 463–524. [Google Scholar]

- Frermann D, Keller BU, Richter DW. Calcium oscillations in rhythmically active respiratory neurones in the brainstem of the mouse. J Physiol. 1999;515:119–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.119ad.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray PA, Rekling JC, Bocchiaro CM, Feldman JL. Modulation of respiratory frequency by peptidergic input to rhythmogenic neurons in the preBötzinger Complex. Science. 1999;286:1566–1568. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5444.1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horne AL, Kemp JA. The effect of omega-conotoxin GVIA on synaptic transmission within the nucleus accumbens and hippocampus of the rat in vitro. Br J Pharmacol. 1991;103:1733–1739. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1991.tb09855.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huguenard JR. Low-threshold calcium currents in central nervous system neurons. Annu Rev Physiol. 1996;58:329–348. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.58.030196.001553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janczewski WA, Onimaru H, Homma I, Feldman JL. Opioid-resistant respiratory pathway from the preinspiratory neurones to abdominal muscles-in vivo and in vitro study in the newborn rat. J Physiol. 2002;545:1017–1026. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.023408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashiwagi M, Onimaru H, Homma I. Correlation analysis of respiratory neuron activity in ventrolateral medulla of brainstem-spinal cord preparation isolated from newborn rat. Exp Brain Res. 1993;95:277–290. doi: 10.1007/BF00229786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llinas R, Sugimori M, Hillman DE, Cherskey B. Distribution and functional significance of the P-type, voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels in the mammalian central nervous system. Trends Neurosci. 1992;15:351–355. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(92)90053-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzon NM, Foehring RC. Characterization of pharmacologically identified voltage-gated calcium channel currents in acutely isolated rat neocortical neurons. II. Postnatal development. J Neurophysiol. 1995;73:1443–1451. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.73.4.1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnelli V, Baldelli P, Carbone E. Antagonists-resistant calcium currents in rat embryo motoneurons. Eur J Neurosci. 1998;10:1810–1825. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellen NM, Janczewski WA, Bocchiaro CM, Feldman JL. Opioid-induced quantal slowing reveals dual networks for respiratory rhythm generation. Neuron. 2003;37:821–826. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00092-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller RJ. Multiple calcium channels and neuronal function. Science. 1987;235:46–52. doi: 10.1126/science.2432656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mironov SL, Richter DW. L-type Ca2+ channels in inspiratory neurones of mice and their modulation by hypoxia. J Physiol. 1998;512:75–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.075bf.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moczydlowski EL, Lucchesi K, Ravindra NA. An emerging pharmacology of peptide toxins targeted against potassium channels. J Membr Biol. 1988;105:95–111. doi: 10.1007/BF02009164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivera BM, Miljanich GP, Ramachandra J, Adams ME. Calcium channel diversity and neurotransmitter release: The ω-conotoxins and ω-agatoxins. Annu Rev Biochem. 1994;63:823–867. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.004135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onimaru H, Arata A, Homma I. Primary respiratory rhythm generator in the medulla of brainstem-spinal cord preparation from newborn rat. Brain Res. 1988;445:314–324. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)91194-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onimaru H, Arata A, Homma I. Neuronal mechanisms of respiratory rhythm generation: an approach using in vitro preparation. Jpn J Physiol. 1997;47:385–403. doi: 10.2170/jjphysiol.47.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onimaru H, Ballanyi K, Richter DW. Calcium-dependent responses in neurons of the isolated respiratory network of newborn rats. J Physiol. 1996;491:677–695. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onimaru H, Homma I. Respiratory rhythm generator neurons in medulla of brainstem-spinal cord preparation from newborn rat. Brain Res. 1987;403:380–384. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90080-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onimaru H, Homma I. Whole cell recordings from respiratory neurons in the medulla of brainstem-spinal cord preparations isolated from newborn rats. Pflugers Arch. 1992;420:399–406. doi: 10.1007/BF00374476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedarzani P, Kulik A, Müller M, Ballanyi K, Stocker M. Molecular determinants of Ca2+-dependent K+ channel function in rat dorsal vagal neurones. J Physiol. 2000;527:283–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00283.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierrefiche O, Champagnat J, Richter DW. Calcium-dependent conductances control neurones involved in termination of inspiration in cats. Neurosci Lett. 1994;184:101–104. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(94)11179-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierrefiche O, Haji A, Bischoff A, Richter DW. Calcium currents in respiratory neurons of the cat in vivo. Pflugers Arch. 1999;438:817–826. doi: 10.1007/s004249900090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez JM, Schwarzacher SW, Pierrefiche O, Olivera BM, Richter DW. Selective lesioning of the cat pre-Bötzinger complex in vivo eliminates breathing but not gasping. J Physiol. 1998;507:895–907. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.895bs.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter DW, Ballanyi K, Schwarzacher S. Mechanisms of respiratory rhythm generation. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1992;2:788–793. doi: 10.1016/0959-4388(92)90135-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter DW, Champagnat J, Jacquin T, Benacka R. Calcium currents and calcium-dependent potassium currents in mammalian medullary respiratory neurones. J Physiol. 1993;470:23–33. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter DW, Spyer KM. Studying rhythmogenesis of breathing: comparison of in vivo and in vitro models. Trends Neurosci. 2001;24:464–472. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01867-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sah P. Ca2+-activated K+ currents in neurons: types, physiological roles and modulation. Trends Neurosci. 1996;19:150–154. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)80026-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JC, Ballanyi K, Richter DW. Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings from respiratory neurons in neonatal rat brainstem in vitro. Neurosci Lett. 1992;134:153–156. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(92)90504-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JC, Ellenberger HH, Ballanyi K, Richter DW, Feldman JL. Pre-Bötzinger Complex: a brainstem region that may generate respiratory rhythm in mammals. Science. 1991;254:726–729. doi: 10.1126/science.1683005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JC, Funk GD, Johnson SM, Feldman JL. Cellular and synaptic mechanisms generating respiratory rhythm: insights from in vitro and computational studies. In: Trouth CO, Millis RM, Kiwull-Schöne HF, Schläfke ME, editors. Ventral Brainstem Mechanisms and Control of Respiration and Blood Pressure. New York: Blackwell Science Inc; 1995. pp. 463–496. [Google Scholar]

- Smith JC, Greer JJ, Liu G, Feldman JL. Neural mechanisms generating respiratory pattern in mammalian brainstem-spinal cord in vitro. J Neurophysiol. 1990;64:1149–1169. doi: 10.1152/jn.1990.64.4.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzue T. Respiratory rhythm generation in the in vitro brain stem-spinal cord preparation of the neoonatal rat. J Physiol. 1984;354:173–183. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swandulla D, Carbone E, Lux HD. Do calcium channel classifications account for neuronal calcium channel diversity? Trends Neurosci. 1991;14:46–51. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(91)90018-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda R, Haji A. Mechanisms underlying post-inspiratory depolarization in post-inspiratory neurons of the cat. Neurosci Lett. 1993;150:1–4. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90093-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonkovic-Capin V, Stucke AG, Stuth EA, Tonkovic-Capin M, Krolo M, Hopp FA, McCrimmon DR, Zuperku EJ. Differential modulation of respiratory neuronal discharge patterns by GABAA receptor and apamin-sensitive K+ channel antagonism. J Neurophysiol. 2001;86:2363–2373. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.86.5.2363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsien RW, Lipscombe D, Madison DV, Bley KR, Fox AP. Multiple types of neuronal calcium channels and their selective modulation. Trends Neurosci. 1988;11:431–438. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(88)90194-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu LG, Borst JGG, Sakmann B. R-type Ca2+ currents evoke transmitter release at a rat central synapse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:4720–4725. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.8.4720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang JF, Randall AD, Ellinor PT, Horne WA, Sather WA, Tanabe T, Schwartz TL, Tsien RW. Distinctive pharmacology and kinetics of cloned neuronal Ca2+ channels and their possible counterparts in mammalian CNS neurons. Neuropharmacology. 1993;32:1075–1088. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(93)90003-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]