Abstract

Connective tissues (CTs), which define bodily shape, must respond quickly, robustly and reversibly to deformations caused by internal and external stresses. Fibrillar (elastin, collagen) elasticity under tension depends on molecular and supramolecular mechanisms. A second intra-/inter-molecular pair, involving proteoglycans (PGs), is proposed to cope with compressive stresses. PG interfibrillar bridges (‘shape modules’), supramolecular structures ubiquitously distributed throughout CT extracellular matrices (ECMs), are examined for potential elastic properties. l-iduronate residues in shape module decoran PGs are suggested to be molecular springs, cycling through alternative conformations. On a larger scale, anionic glycosaminoglycan (AGAG) interfibrillar bridges in shape modules are postulated to take part in a sliding filament (dashpot-like) process, which converts local compressions into disseminated tensile strains. The elasticity of fibrils and AGAGs, manifest at molecular and larger-scale levels, provides a graduated and smooth response to stresses of varying degrees. NMR and rheo NMR, computer modelling, electron histochemical, biophysical and chemical morphological evidence for the proposals is reviewed.

Elastic deformation

Central functions evolved within reproducible permanent shapes defined by the CTs (skin, cartilage, etc.). CTs maintain shape flexibly, elastically absorbing deformations caused by movement, respiration, etc. and contact with the environment. CT mechanical properties are expressable in terms of springs and dashpots (e.g. Viidik, 1973). The challenge is to relate engineering concepts to tissue chemical morphology. Supramolecular organisations attract growing interest. In particular the shape modules (Scott & Thomlinson, 1998, see below), ubiquitous building blocks in all animal CTs, attract a fresh analysis of tissue mechanics. Are stability and flexibility reconcilable at the molecular level?

CT ECMs cope with tensile and compressive mechanical stresses. Tension is transmitted and resisted by protein (collagen, elastin) fibres. Compression is opposed by water-soluble AGAGs, e.g. chondroitin sulphate (CS) because they tend to swell in solution (a) entropically, as do all polymers in good solvents, (b) electrostatically by mutual repulsion of their many charges and (c) by Donnan osmotic pressure of the polyanionic AGAG counterions (Scott, 1975). AGAGs inflate interfibrillar spaces, forming channels through which small water-soluble molecules move.

Mechanical properties correlate with concentrations and proportions of fibrous protein and carbohydrate AGAG in the tissue, from the vitreous humor of the eye, a weak gel containing < 1 % by weight of fibres and AGAG, to the toughest tendons, with over 70 % fibre. Harder tissues such as cartilage and corneal stroma contain much expansile AGAG, like car tyres inflated to a high pressure.

The expansile role was proved by precipitating AGAGs in the tissues (e.g. cartilage (Sokoloff, 1963) and cornea (Hedbys, 1961)) and then demonstrating that turgor and elasticity were thereby lost. Precipitated AGAG occupies much smaller volumes than dissolved AGAG, effectively removing the AGAG from the tissue.

Water entrained in AGAG domains was proposed to translocate reversibly like shock absorber fluid (Scott, 1975) but the tissue elements that accommodate displaced water and return it quickly and precisely to its origin post deformation were not identifiable. The fibrils and AGAGs must possess (or be part of) structures with intrinsic elasticity. Mechanisms involving collagen and elastin fibrils are known, but AGAG molecular and supramolecular features that may confer elasticity are uncharted

Fibril-proteoglycan organisation and shape modules

The above scheme poses two questions: (a) how do ECMs maintain their shape-defining organisation against mechanical stress and (b) how do PGs regain their size, shape and position after compression/decompression? Robust interfibrillar connections must hold the fibrils together against AGAG swelling pressure and there must be stable PG-fibril relationships, since if PGs moved with fluid flows the tissue shape would vary with its stress history. It was suggested that PGs were trapped in critically sized spaces in the fibrillar meshwork (Scott, 1975), but there is no evidence for such stable, precise organisations.

The PGs themselves perform these tasks. Using Cupromeronic blue to demonstrate tissue polyanions by electron microscopy (Scott, 1985), AGAG bridges were demonstrated (Scott, 1988) orthogonally spanning collagen fibrils in tendons, skin, and other ECMs in many species. AGAG chain lengths determine interfibrillar gap widths (Scott, 1992a). The AGAGs belong to PGs termed decorins (Ruoslahti, 1988) (now decoran, Liebecq, 1997), because they decorate the collagen fibril. PG bridges probably orient the fibrils, since they are the only observable regular interfibrillar connections. They are part of shape modules (Fig. 1A)(Scott & Thomlinson, 1998), so-called because of their tissue-organising function. Shape modules were lacking in ECMs produced by cultured cells from a human foetus unable to express the decoron gene. Consequently ECM organisation was totally deranged (Scott et al. 1998).

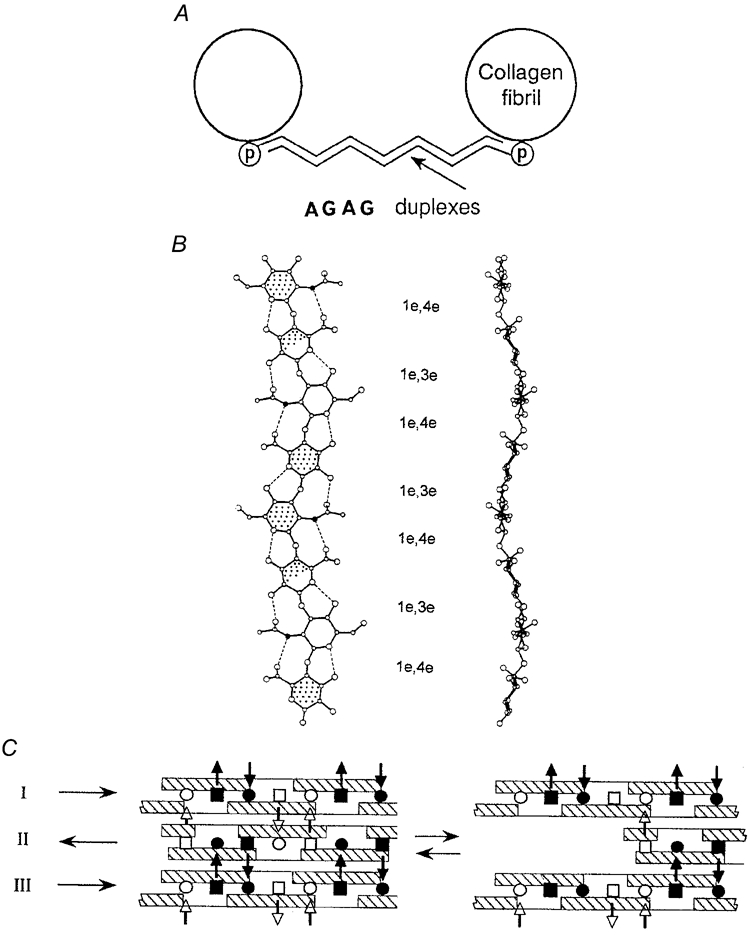

Figure 1.

A, the shape module. Antiparallel proteoglycan AGAG aggregates (shown as duplexes) link collagen fibrils (in section); (p), proteoglycan protein (Scott, 1992a). B, plan (left) and elevation of two-fold helices preferred (in solution) by shape module AGAGs (chondroitins, keratans) and HA (Scott, 1995) in which all glycosidic bonds are equatorial 1–3, 1–4 and hydrophobic patches (stippled) are identically placed, as are the waves and inter-residue H-bonds (dotted lines). Filled circles, N atoms. Hyaluronan (HA) is illustrated. C, side views of tertiary structures of AGAGs with twofold helical secondary structures as in B. Hydrophobic patches (cross-hatched) form hydrophobic bonds and acetamido-NH (▪, □) H-bonds to carboxylate (•, ○) on the adjacent AGAG. Filled symbols are below, and open symbols above, the plane of the diagram. The waves shown in B complement each other in these antiparallel aggregates. Arrows on the left indicate reducing end direction (Scott & Heatley, 1999). Lateral displacement of chain II with respect to chains I and III caused by movement apart of the shape module fibrils (A, above) is reversible, driven by the energy gain in reforming the broken hydrophobic and H-bonds.

Electron histochemistry revealed four PG-binding sites per collagen fibril D period (≈65 nm), at the a, c, d, and e bands (Scott, 1988) (Fig. 2). The amount of bound PG per gram of tissue depends on the number of sites occupied by PG per fibril unit. Decorans in tendons, corneal stroma, etc. bind at the d and e bands. Bands a and c are occupied by keratan sulphate (KS)-conjugated PGs in corneal stroma. Consequently more polyanion is attached to collagen fibrils in cornea than in tendon, giving more swelling pressure and a stiffer structure.

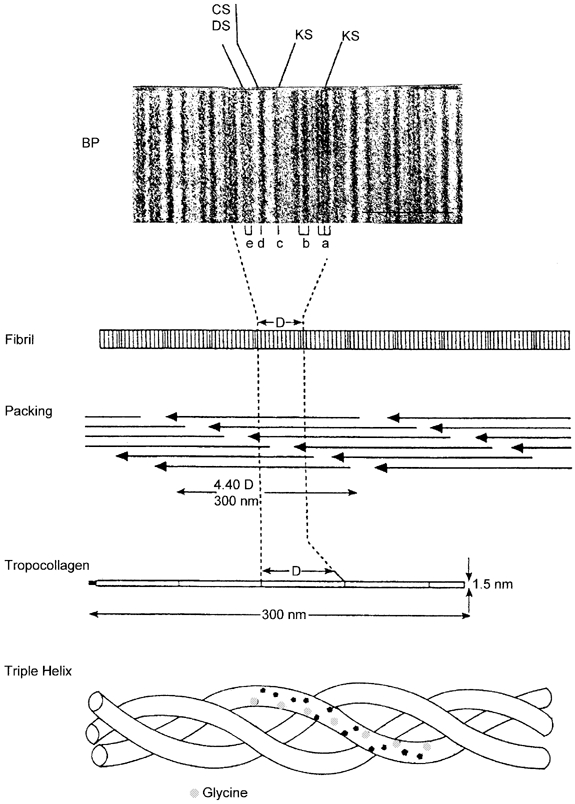

Figure 2. Collagen fibril structure and PG-fibril interactions.

Triple-helical tropocollagen packs spontaneously into a quarter-staggered array in the fibril, on the surface of which bands of polar and non-polar amino acids show up after e.g. UO22+ staining as a–e bar codes (BP, banding pattern). Each a-e repetition is a D period, in which four PG binding sites at the d, e (decoran) and a, c (KS PGs) bands are located (Scott, 1988).

Shape module structure

Decorans are horseshoe-shaped leucine-rich-repeat ≈45 kDa proteins (decorons) to which a dermochondan sulphate (DS) AGAG chain is linked near the N-terminal (Scott, 1996). AGAGs of the keratan and chondroitin families are attached to similar proteins in lumican, fibromodulan, etc. Decoran binds non-covalently to collagen fibrils (Scott, 1988) and its covalently linked DS chain stretches across to a neighbouring collagen fibril, duplexing head-to-tail (antiparallel) with a DS chain from decoran attached to that fibril, thereby producing an interfibrillar bridge (Fig. 1A) (Scott, 1991). Since the AGAGs link identical D period (e.g. d/e) bands, they hold packages of fibrils in a strikingly parallel alignment, oriented in register. Until shape modules were seen there was no explanation for this in-register parallel order.

Biochemical evidence from tissues (Scott et al. 1997) and on isolated decoran and reconstituted fibrils of type I collagen (Yu et al. 1993) confirmed the positions of the binding sites and that decoron associates with specific amino acid sequences at these positions (Scott & Glanville, 1993).

Decoran DS chains spontaneously aggregate in solution (Fransson, 1976), antiparallel, as shown by electron microscopy (Ward et al. 1987). This interaction underpins the AGAG bridges, and together with evidence of PG protein-collagen association (above), suggests the shape module structure in Fig. 1A.

The protein fibrils (collagen and elasin)

Collagen (characterised by a tripeptide repeating unit, gly-X-Y rich in hydroxyproline) is produced in genetically distinct forms, of which types I, II and III are relevant. Type I collagen (‘collagen vulgaris’), the major protein in the body, predominates in skin, bone, corneal stroma, etc., whereas the distributions of types II and III collagen are more restricted. Spontaneous specific aggregation of the long (300 nm) thin (1.5 nm) triple helical collagen molecules produces fibrils, subsequently stabilised by enzymatically induced covalent crosslinks (Fig. 2). Collagen fibrils in tendon (type I collagen) are packets of helically wound protofibrils of 10–15 nm diameter (Scott, 1990), which in cartilage are aligned along the fibril (type II collagen) axis (Marchini & Ruggeri, 1984). AGAGs occur axially and regularly between protofibrils (Scott, 1990).

Tendon collagen fibres stretch elastically to strains of ≈10 %, beyond which irreversible damage occurs. Unstretched tendon has an ordered structure characterised by transverse bands in transmitted polarised visible light with periodicities of ≤100 microns, possibly due to crimps in fibre bundles (Gathercole & Keller, 1991), for which, however, there is no simple chemical or physical explanation. This pattern disappears reversibly at ≈5 % strain, suggesting elastic rearrangements of fibrils. X-ray diffraction patterns of unstretched tendon sharpen under tension, indicating increased supramolecular order. Helicoid protofibrils within tendon fibrils may stretch elastically to a parallel arrangement (cf. Castellani et al. 1983), possibly after crimp straightening.

Fibrils which are not birefringent or containing helicoid protofibrils, e.g. as in cartilage (Marchini & Ruggeri, 1984; Gathercole & Keller, 1991) are either not elastic, or an unidentified mechanism for reversible deformation is available to them.

Tensile stresses change the morphology of collagen aggregates rather than the shapes of collagen molecules.

The elastin molecule (tropoelastin), however, is elastic. It is a coiled 68 kDa protein with a high content of hydrophobic amino acids. Tropoelastin aggregates to fibrils, later stabilised by cross-linking via a lysyl-oxidase-dependant process, analogous to that undergone by collagen. Elastin elongates and straightens under tension (≤200 %), exposing hydrophobic surfaces to the aqueous environment and losing entropy from the coiled configuration. Both events are energetically unfavourable. Re-coiling is driven by release of this energy. Stretched elastin stores energy which is utilised e.g. in smoothing out blood flow pulsation in arteries.

Elastin and collagen fibres work in tandem. Elastin resistance is supplemented, and superseded, as strain increases within a collagen fibril framework, which determines the maximum reversible deformation. Collagen fibrils are disseminated throughout the animal world. Elastin is one of a group of elastomeric proteins (e.g. resilin) of differing compositions and sizes, with restricted distributions (e.g. in chordates, insects, etc.).

Whereas collagen fibrils associate specifically with decorans, thereby fundamentally affecting ECM elasticity (see below), no evidence of regular, specific PG-elastin fibril association has been seen.

AGAG interfibrillar bridges

Shape module stability and elasticity depend on the structure of the AGAG bridges. AGAG chains aggregate – despite strong electrostatic mutual repulsion – via van der Waals forces, hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic bonding, which require close approach of the participants, complementary shapes and secondary structures. ECM AGAGs (CS, DS, KS and HA) all have 1 : 3, 1 : 4 β-linked (1e3e, 1e4e) polymer backbones (Fig. 1). HA is prototypical. It has one primary structure, which is independant of molecular mass, compared with CS, DS and KS where patterns of sulphation provide for over16 different disaccharides. A modest chain-length of 30 disaccharides therefore could encompass 1630 different molecules, a figure which rises exponentially if epimerisation of some of the sugars occurs, as in DS (Scott, 1995).

The many similarities of these AGAGs relate to their roles in shape modules. In solution they prefer to take up flat, tape-like twofold helical configurations, as shown by NMR (Hounsell, 1989; Scott et al. 1995) and confirmed by modelling and computer simulation (Moulabbi et al. 1997). Both faces of the tape are identical but antiparallel, interacting exactly similarly, but oriented at 180 deg to each other. HA, KS, and CS twofold helices have repeated hydrophobic patches on each face, which can take part in hydrophobic bonding (Fig. 1B).

HA, CS6, KS and DS form homo- and hetero-aggregates (Scott, 1992b) (Table 1). HA self-aggregation is stabilised by hydrophobic and H-bonding between anti-parallel twofold helices in sterically-demanding complementarity. The hydrogen donors (acetamido-NH) and acceptors (carboxylates) were identified by 13C NMR and modelling (Scott & Heatley, 1999) (Fig. 1C).

Table 1.

Aggregating ECM anionic glycosaminoglycans

| Techniques demonstrating aggregation | References | |

|---|---|---|

| Self-aggregation | ||

| Hyaluronan | a, b, c, d | Scott, 1991; Scott et al. 1992; Scott & Heatley, 1999; Scott et al. 2003. |

| Keratan sulphate | e | Pfeiler, 1988. |

| Chondroitin | a | Scott et al. 1992. |

| Chondroitin-6-sulphate | a, b | Scott et al. 1992. |

| Dermochondan sulphate | b, e, f, g | Ward et al. 1987; Fransson & Coster, 1979; Fransson et al. 1979. |

| Heteroaggregation | ||

| Hyaluronan/chondroitin-6-sulphate | f, g | Nishimura et al. 1998; Sabaratnam et al. 2002. |

| Non-aggregating ECM anionic glycosaminoglycans | ||

| Chondroitin-4-sulphate | a, b, c | Scott, 1992a,b; Scott et al. 2003. |

| Highly sulphated AGAGs | a, b | Scott, 1992a. |

a, computer simulation; b, rotary-shadowing electron microscopy; c, electron histochemistry; d, NMR; e, gel chromatography; f, light scattering; and g, viscometry.

Salient features of the HA tertiary structure extrapolate to the other AGAGs. DS aggregates dissociate in 1m urea solution, suggesting involvement of H-bonds (Fransson, 1976). DS aggregation in dimethylsulphoxide solution was much reduced by competing lipids, implying disruption of hydrophobic DS-DS interactions (Scott et al. 1995)

Stability after chemical treatments in the tissues of AGAG bridges visualised by electron histochemistry – crucially the disruptive effects of urea in the presence of non-ionic detergent, which were much greater than either separately – was compatible with postulated hydrophobic- and H-bonded DS aggregates (Scott & Thomlinson, 1998).

The results of gel chromatography of KS (Pfeiler, 1988) and light scattering studies on DS (Fransson et al. 1979) implied that both formed duplexes. DS chains from cornea and cirrhotic liver ECMs are homodisperse (Stuhlsatz et al. 1993), allowing aggregation without loose ends in AGAG bridges (Fig. 1A).

Elastic interfibrillar bridges

Shape modules occur at ≈60 nm intervals along collagen fibrils (Fig. 2). Their numerous Lilliputian AGAG ropes hold the Gulliverian tissue together. AGAG bridge lengths cannot be immutable, since stresses would then be transmitted inelastically, risking rupture of shape modules. Irreversible damage would occur during tissue swelling if the bridges were inelastic, and cornea, for example, swells reversibly over a considerable range (Fatt, 1978). AGAG bridges must deform elastically in their shape-maintaining physiology. Intra- and inter-molecular mechanisms are proposed.

Intramolecular elasticity of l-iduronate

Four sugars present in ECM AGAGs, viz. galactose (KS), N-acetylglucosamine (HA), N-acetylgalactosamine (DS and CS) and glucuronate (DS, HA and CS) are stable C1 chair conformers in physiological conditions. C1, the unfolded form of the pyranose ring, cannot stretch because of tight packing of ring carbons and oxygen therein. Extended chains of HA, CS and KS therefore transmit and resist tensile stresses with minimal elongation. The fifth sugar, l-iduronate (IdoUA), characteristic of DS, differs markedly from GlcUA, its C5 epimer in CS and HA, in taking up alternative conformations (C1, 1C and 2S0; Fig. 3A) with minimal energy exchange, as shown by NMR spectroscopy and computer simulations (Casu et al. 1988)). This plasticity permits DS and heparin to interact with e.g. periodate (Scott et al. 1995) and antithrombin (Hricovini et al. 2001) in ways not available to GlcUA-containing AGAGs. C1 IdoUA is extended, but 1C and 2S0 are more compact and AGAG chains containing them are shorter (Fig. 3A). A pull across the pyranose ring along the glycosidic bonds on the chain axis would convert the compact conformers into extended C1, elongating the molecule (Fig. 3B). Since compact conformers are preferred over C1 in water (Casu et al. 1988), the chain would shorten to the original length on removal of tension, i.e. the process would be elastic. A small stress could produce a 5–10 % strain. An analogous increase in compact forms in DS was seen by NMR when the mutual repulsion of anionic charges, which elongates the chain (the electroviscous effect), was diminished by addition of electrolyte (Casu, 1993) – a direct demonstration of intramolecular AGAG elasticity.

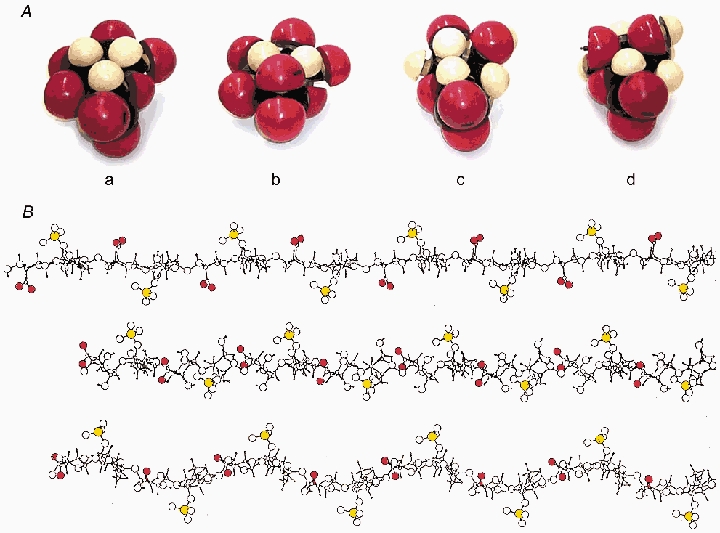

Figure 3.

A, Courtauld space-filling models of (a) GlcUA, (b) IdoUA C1, (c) IdoUA 2So and (d) IdoUA 1C, carboxylate at bottom. Red, oxygen; white, hydrogen. The DS longitudinal axis runs left-right through the equator of each. c) and d) are the more compact on this axis. B, elevation views of stick-and-ball models of twofold helical DS homopolymers comprising exclusively: top, 4C1 IdoUA; middle, 1C4 IdoUA; bottom, 2So IdoUA. Carboxylate oxygens in red and sulphate ester sulphur in yellow. Drawn using Artist for QUANTA programme (cf. Scott et al. 1992). Compact IdoUAs confer shorter chain lengths (middle and bottom) for the same number of sugar units. Under tension these could elongate to longer (top) configurations.

This ‘reversible deformation under tensile stress’ function (i.e. IdoUA as a spring) has not been proposed previously and the appropriate rheo NMR experiment (cf. Fischer et al. 2002) remains to be done, but it throws light on DS mechanics. Ratios of IdoUA/GlcUA in DS vary without obvious reason from ≈10 % to over 90 % depending on the tissue. The proposed elastic function implies that this ratio should be higher in more flexible tissues and indeed, skin and tendon have higher ratios than rigid cornea and articular cartilage.

This mechanism allows quick, low-energy and small elastic adjustments, but big deformations occur during vigorous movement and hard contacts. Corneal stroma can swell fivefold, reversibly (Fatt, 1978). Larger-scale processes must cope with such eventualities.

The sliding filament model

It is proposed that reversible longitudinal slippage within shape module AGAG bridges sustains mechanical stresses elastically (Fig. 1C and Fig. 4). Reversible interactions between AGAGs are optimised (the minimum energy situation) when all available binding sites (hydrophobic and hydrogen bonds) are engaged. The AGAG tertiary structure therefore reverts to this situation, post stress, if it can (Fig. 1C and Fig. 4).

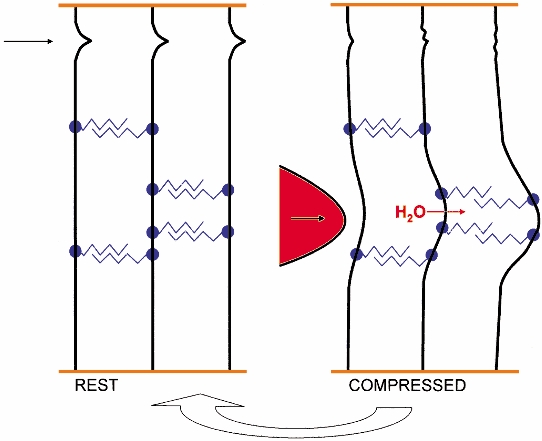

Figure 4.

Scheme of reversible deformation involving shape module AGAG reversible slippage (right), which converts local compression into delocalised tensile deformation (right). Collagen fibrils (vertical black) are bridged by shape modules, antiparallel AGAG chains (zigzags) covalently linked to PG protein (filled circles) which bind to fibrils at specific binding sites (see Fig. 2). The arrow (top left) indicates a functional crimp, which however cannot be equated with a known primary or secondary structure (see text). Orange horizontal lines indicate ECM into which the fibrils are anchored. Left half, ‘REST’ diagrams the positions of the AGAG chains, fibrils, etc. in an unstressed ECM. Right half, ‘COMPRESSED’ shows a compressive force (as a red probe pressing in the direction of the arrow) impacting on the ECM. The collagen fibril crimp yields under the impact and tissue H2O is displaced into neighbouring spaces where it exerts pressure along the AGAG aggregates, causing slippage between the aggregate participants and unwinding of the fibril crimp. Open arrow, from right to left at bottom, indicates reversal of the slippage and crimp distortion to the resting state on removal of the compressive stress, contingent on the return to the original position of the tissue H2O (see text). Not to scale.

Avidity between AGAG chains is a cooperative phenomenon, depending on the number N of interacting segments, which contribute N individual energies to the total interaction. A sliding filament gives up energy of interaction as it engages with shorter lengths of its partner(s) after slippage. This energy is recovered when the chains re-engage over their whole length, on release of stress.

Measures of individual contributions from computer simulations serve as a basis for comparison between AGAGs according to their interactive capacity. Equilibria between e.g HA, KS and DS monomers and aggregates, observed by NMR, gel chromatography and light scattering, respectively, (see Table 1) suggest that most or all of the AGAG is in the aggregated form and that an equilibrium constant for DS (104; Fransson et al. 1979) is compatible with the modes of binding (hydrophobic and hydrogen bonding) discussed in this paper.

This model predicts that strains are irreversible if overlaps between chains decrease beyond a critical level. In fact excessive swelling in, for example, corneal stroma is irreversible (Fatt, 1978)

This mechanism is particularly relevant during compressive stress. Movement of aqueous fluid under pressure reversibly stretches AGAG strain-bearers distant from the stress (Fig. 4). Compressive stresses are thereby converted into tensile stresses throughout the tissue. The IdoUA spring could absorb small deformations according to this scheme, prior to slippages of AGAG chains.

This model of elasticity resembles the sliding-filament model of muscle contraction, except that initial movement in the ECM is passive, with energy being released on the restoration.

If, in engineering terms, IdoUA is a spring, the sliding AGAG filament resembles a dashpot.

Reversible deformation in AGAG tertiary structures

Deformation must be completely reversible on releasing the stress. HA behaviour in aqueous solution suggests that this is so. The HA tertiary structure has an NMR signature, the broadening of the 13C-acetamido C=O signal, due to hindered rotation of the H-bonded acetamido-NH (Fig. 1C). Changes to the tertiary structure are followed (Scott & Heatley, 2002) by monitoring the breadth of this resonance. The tertiary structure is reversibly disrupted by cycling between alkaline and neutral pHs, by heating and/or cooling and by shear stress (Fischer et al. 2002). Solution viscosity drops and rapidly recovers as the intervention ceases. The broad C=O NMR signal sharpens with disaggregation (‘denaturation’) and then broadens when conditions return to physiological (i.e. the tertiary structure ‘renatures’). The shear stress data are directly relevant to the sliding filament hypothesis, implying that H-bonded structures are disrupted by shear and that they reform completely after shearing. HA tertiary structures in streptococcal capsules may help to maintain chains of bacteria against mechanical activity by their host (Scott et al. 2003).

Similar behaviour is postulated for AGAGs in shear-stressed shape modules. DS solution viscosity drops at high shear and recovers at low shear (Fransson et al. 1979), as do HA solutions, but there are no NMR data implicating specific DS-DS binding.

Sulphation and aggregation

Although DS properties (antiparallel duplexing, hydrophobic and H-bonding in aggregates) are appropriate to AGAG bridges, important questions posed by sulphation and epimerisation require further discussion before applying the HA analogy in entirety to DS.

Mutual electrostatic repulsion of AGAGs is outweighed by hydrophobic and hydrogen bonding – as in the DNA double helix. Electrostatic repulsion between AGAGs increases on addition of sulphate ester groups, which also sterically hinder approach of other AGAGs when suitably placed. It was calculated that HA and chondroitin-6-sulphate (CS6) could self-aggregate and aggregate with each other but that chondroitin-4-sulphate (CS4) could not (Scott et al. 1992) because of the steric and electrostatic hindrance offered by 4-sulphate groups, which cluster along the centre line of 2-fold helical CS4. The sulphates of CS6 are at the periphery of the 2-fold helix, where their charge is disseminated and steric hindrance to close packing of the tape-like polyanions is minimised. These predictions were validated by electron microscopy (Scott et al. 1992, 2003), gel exclusion chromatography and viscometry (Nishimura et al. 1998) (Table 1). HA-CS6 interactions have a role in synovial physiology (Sabaratnam et al. 2002).

Some DS sequences are 6-sulphated (Roughley & White, 1989), potentially aggregating like CS6. DS 4-sulphate groups are close to the polymer axis and on both sides of the 2-fold helix in the fully sulphated form. Aggregation should be difficult, as for CS4. Since DS aggregation has been observed in a variety of conditions (Fransson, 1976), either the electrostatic and/or steric hindrance posed by equatorial C4 sulphate groups is reduced or short range attractions are stronger. Hydrophobic bonding probably decreases in sulphated DS, since sulphation is linked to epimerisation and the 1C and 2So epimers have smaller hydrophobic patches (Fig. 3A) than GlcUA, with CHs oriented equatorially at the rim of the tape and replaced by axial OH groups on the interacting tape face. Where in GlcUA there was a hydrophobic patch of 3CHs, in 1C IdoUA there are polar OHs, ruling out hydrophobic bonding at that point. Possibly the axial OH groups participate in additional intermolecular H-bonding.

DS sulphation is sometimes very low (Laurent & Anseth, 1961; Stuhlsatz et al. 1993) to the point of qualifying as ‘chondroitin’ (Davidson & Meyer, 1954) and these structures would aggregate easily, like HA which is non-sulphated. DSs with 50 % regular 4-sulphation (i.e. alternate non-sulphated disaccharides) have the sulphate groups on one face of the tape-like 2-fold helix (Fig. 1B). Computation showed that aggregation can take place on the non-sulphated face (Scott et al. 1992). This mechanism could operate for porcine corneal DS, which contains considerable amounts of a tetrasaccharide with alternating non-sulphated and sulphated disaccharides and a net sulphation of ≤ 50 % (Stuhlsatz et al. 1993). Aggregation occurred more readily when ≈50 % of the uronate was IdoUA, implying sulphation of ≈50 %. This degree of regular sulphation would allow duplex formation and duplexes were indeed indicated by light scattering (Fransson et al. 1979).

DS may aggregate in several ways to form bridges, producing structures with different mechanical properties in different ECMs. Precise modelling, as of HA and CS6, has not been done, because of the complications of multiple conformer shapes and ignorance of where these shapes are localised within the polymer.

Cartilage aggrecan

The characteristic cartilage PG (aggrecan) has many AGAG chains attached to its protein core, equivalent to a multiplicity of decorans in parallel. Aggrecans could form numerous antiparallel AGAG duplexes. Aggregating CS6, KS and undersulphated CS chains are present in aggrecan-and aggrecan does self-aggregate (Sheehan et al. 1978). Since aggrecan is multivalent, it can aggregate in three dimensions, resulting in dense and highly cooperative structures able to undergo elastic deformation, distributed among many aggrecan molecules. Heavy forces could be supported, as in knee joint cartilages, which are rich in aggrecan.

Acknowledgments

The MRC supported this work via Co-operative Group Grant G9900933.

References

- Castellani PP, Moricutti M, Franchi M, Ruggeri A, Roveri N. Arrangement of microfibrils in collagen fibrils in the rat tail. Cell Tiss Res. 1983;234:735–743. doi: 10.1007/BF00218664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casu B. Discussion. In: Scott JE, editor. Dermatan Sulphate Proteoglycans: Chemistry, Biology, Chemical Pathology. London: The Biochemical Society; 1993. p. p. 76. [Google Scholar]

- Casu B, Petitou M, Provasoli M, Sinay P. Conformational flexibility: a new concept for explaining binding and biological properties of iduronic acid-containing glycosaminoglycans. Trends Biochem Sci. 1988;13:221–225. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(88)90088-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson EA, Meyer K. Chondroitin, a new mucopolysaccharide. J Biol Chem. 1954;211:605–611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatt I. Physiology of the eye. Boston and London: Butterworths; 1978. chap. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer E, Callaghan P, Heatley F, Scott E. Shear flow affects secondary and tertiary structures in hyaluronan solution as shown by rheo-NMR. J Mol Struct. 2002;602–603:303–311. [Google Scholar]

- Fransson L-A. Interaction between dermatan sulphate chains. I. Affinity chromatography of co-polymeric galactosaminoglycans on dermatan sulphate substituted agarose. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1976;437:106–115. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(76)90351-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fransson L-A, Coster L. Interaction between dermatan sulphate chains. II Structural studies on aggregating glycan chains and oligosaccharides with affinity for dermatan sulphate-substituted agarose. Biochim Biophy Acta. 1979;582:132–144. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(79)90296-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fransson L-A, Nieduszynski IA, Phelps CF, Sheehan JK. Interactions between dermatan sulphate chains. III. Light scattering and viscometry studies of self-association. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1979;586:179–188. [Google Scholar]

- Gathercole LJ, Keller A. Crimp morphology in fibril-forming collagens. Matrix. 1991;11:214–234. doi: 10.1016/s0934-8832(11)80161-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedbys BO. The role of polysaccharides in corneal swelling. Exp Eye Res. 1961;1:81–91. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(61)80012-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hounsell EF. Structural and conformational analysis of keratan sulphate oligosaccharides and related carbohydrate structures. In: Greiling H, Scott JE, editors. Keratan Sulphate Chemistry, Biology, Chemical Pathology. London: The Biochemical Society; 1989. pp. 12–15. [Google Scholar]

- Hricovinii M, Guerrini M, Bisio A, Torri G, Petitou M, Casu B. Conformation of heparin pentasaccharide bound to antithrombin III. Biochem J. 2001;359:265–272. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3590265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurent TC, Anseth A. Studies on corneal polysaccharides. II Characterisation. Exp Eye Res. 1961;1:99–105. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(61)80014-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebecq C. IUPAC-IUBMB Joint Commission on Biochemical Nomenclature (JCBN) and Nomenclature Committee of IUBMB (NC-IUBMB) Eur J Biochem. 1997;247:733–739. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.733_1.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchini M, Ruggeri A. Ultrastructural aspects of freeze dried collagen fibrils. In: Ruggeri A, Motta PM, editors. Ultrastructure of the Connective Tissue Matrix. Boston: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers; 1984. pp. 89–94. [Google Scholar]

- Moulabbi H, Broch H, Robert L, Vasiescu D. Quantum molecular modelling of hyaluronan. Theochem. 1997;395–396:477–508. [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura M, Yan W, Mukudai Y, Nakamura K, Kawata M, Kawamoto T, Noshiro M, Hamada T, Kato Y. Role of chondroitin sulphate-hyaluronan interactions in the viscoelastic properties of extracellular matrices and fluids. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1380:1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(97)00119-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiler E. Isolation and partial characterisation of a novel keratan sulphate proteoglycan from metamorphosing bone fish (Albula) larvae) Fish Physiol Biochem. 1988;4:175–181. doi: 10.1007/BF01871744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roughley PJ, White RJ. Dermatan sulphate proteoglycans of human articular cartilage. Biochem J. 1989;262:823–827. doi: 10.1042/bj2620823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruoslahti E. Structure and biology of proteoglycans. Ann Rev Cell Biol. 1988;4:229–255. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.04.110188.001305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabaratnam S, Coleman PJ, Badrick E, Mason RM, Levick JR. Interactive effect of chondroitin sulphate C and hyaluronan on fluid movement across rabbit synovium) J Physiol. 2002;540:271–284. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott JE. Composition and structure of the pericellular environment: physiological function and chemical composition of pericellular proteoglycan (an evolutionary view) Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1975;271:235–242. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1975.0047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott JE. Proteoglycan histochemistry-a valuable tool for connective tissue biochemists. Coll Rel Res. 1985;5:541–598. doi: 10.1016/s0174-173x(85)80008-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott JE. Proteoglycan-fibrillar collagen interactions. Biochem J. 1988;252:313–323. doi: 10.1042/bj2520313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott JE. Proteoglycan-collagen interactions and subfibrillar structure in collagen fibrils. Implications in the development and aging of connective tissues. J Anat. 1990;169:23–35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott JE. Proteoglycan:collagen interactions and corneal ultrastructure. Biochem Soc Trans. 1991;19:877–881. doi: 10.1042/bst0190877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott JE. Morphometry of Cupromeronic blue-stained proteoglycan molecules in animal corneas, versus that of purified proteoglycans stained in vitro, implies that tertiary structures contribute to corneal ultrastructure. J Anat. 1992a;180:155–164. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott JE. Supramolecular organisation of extracellular matrix glycos-aminoglycans, in vitro and in the tissues. FASEB J. 1992b;6:2639–2645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott JE. Extracellular matrix, supramolecular organisation and shape. J Anat. 1995;187:259–269. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott JE. Proteodermatan and proteokeratan sulfate (decorin, lumican/fibromodulin) proteins are horseshoe shaped). Implications for their interactions with collagen. Biochemistry. 1996;35:8795–8799. doi: 10.1021/bi960773t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott JE, Chen Y, Brass A. Secondary and tertiary structures involving chondroitin and chondroitin sulphates in solution, investigated by rotary shadowing-electron microscopy and computer simulation. Eur J Biochem. 1992;209:675–680. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb17335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott JE, Dyne KM, Thomlinson AM, Ritchie M, Bateman J, Cetta G, Valli M. Human cells unable to express decoron produced disorganised extracellular matrix lacking ‘shape modules’ (interfibrillar proteoglycan bridges) Exp Cell Res. 1998;243:59–66. doi: 10.1006/excr.1998.4089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott JE, Glanville RW. Homologous sequences in fibrillar collagens may be proteoglycan binding sites. Biochem Soc Trans. 1993;21:123S. doi: 10.1042/bst021123s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott JE, Heatley F. Hyaluronan forms specific stable cooperative tertiary structures in solution. A 13C n.m.r. study. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:4850–4855. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.4850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott JE, Heatley F. Biological properties of hyaluronan in aqueous solution are controlled and sequestered by reversible tertiary structures, defined by NMR spectrosopy. Biomacromolecules. 2002;3:547–553. doi: 10.1021/bm010170j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott JE, Heatley F, Wood B. Comparison of secondary structures in water of chondroitin-4-sulfate and dermatan sulfate: Implications in the formation of tertiary structures. Biochemistry. 1995;34:15467–15474. doi: 10.1021/bi00047a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott JE, Ritchie M, Glanville RW, Cronshaw AD. Peptide sequences in glutaraldehyde-linked proteodermatan sulphate:collagen fragments from rat tail tendon locate the proteoglycan binding sites. Biochem Soc Trans. 1997;25:S663. doi: 10.1042/bst025s663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott JE, Thomlinson AM. The structure of interfibrillar proteoglycan bridges (‘shape modules’) in extracellular matrix of fibrous connective tissues and their stability in various chemical environments. J Anat. 1998;192:391–405. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.1998.19230391.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott JE, Thomlinson AM, Prehm P. Supramolecular organisation in streptococcal pericellular capsules is based on hyaluronan tertiary structures. Exp Cell Res. 2003;285:1–8. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(02)00088-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan JK, Hardingham TE, Muir HM, Phelps C. Self-association of proteoglycan subunits from pig laryngeal cartilage. Biochem J. 1978;171:109–11. doi: 10.1042/bj1710109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokoloff L. Elasticity of articular cartilage, effect of ions and viscous solutions. Science. 1963;141:1055–1057. doi: 10.1126/science.141.3585.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuhlsatz HW, Hoffmeister MG, Kock R, Becker G, Lennarz L, Greiling H. Studies on the domain structure of corneal dermatan sulphate. In: Scott JE, editor. Dermatan Sulphate Proteoglycans Chemistry, Biology, Chemical Pathology. London: The Biochemical Society; 1993. pp. 27–39. [Google Scholar]

- Viidik A. Rheology of skin with special reference to age-related parameters and their possible correlation to structure. In: Robert L, editor. Front Matrix Biology. Vol. 1. Basel: Karger; 1973. pp. 157–189. [Google Scholar]

- Ward NP, Scott JE, Coster L. Dermatan sulphate proteoglycans from sclera examined by rotary shadowing and electron microscopy. Biochem J. 1987;242:761–765. doi: 10.1042/bj2420761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L, Cummings C, Sheehan JK, Kadler KE, Holmes DF, Chapman JA. Visualization of individual proteoglycan-collagen interactions. In: Scott JE, editor. Dermatan Sulphate Proteoglycans Chemistry, Biology, Chemical Pathology. London: The Biochemical Society; 1993. pp. 183–188. [Google Scholar]