Abstract

Spontaneous activity in the central nervous system is strongly suppressed by blockers of gap junctions (GJs), suggesting that GJs contribute to network activity. However, the lack of selective GJ blockers prohibits the determination of their site of action, i.e. neuronal versus glial. Astrocytes are strongly coupled through GJs and have recently been shown to modulate synaptic transmission, yet their role in neuronal network activity was not analysed. The present study investigated the effects and site of action of the GJ blocker, carbenoxolone (CBX), on neuronal network activity. To this end, we used cultures of hippocampal or cortical neurons, plated on astrocytes. In these cultures neurons display spontaneous synchronous activity and GJs are found only in astrocytes. CBX induced in these neurons a reversible suppression of spontaneous action potential discharges, synaptic currents and synchronised calcium oscillations. Moreover, CBX inhibited oscillatory activity induced by the GABAA antagonist, bicuculline. These effects were not due to blockade of astrocytic GJs, since they were not mimicked nor occluded by endothelin-1 (ET-1), a peptide known to block astrocytic GJs. Also, these effects were still present in co-cultures of wild-type neurons plated on astrocytes originating from connexin-43 (Cx43) knockout mice, and in neuronal cultures which contain few isolated astrocytes. CBX was not likely to exert its effect through neuronal GJs either, as immunostaining for major neuronal connexins (Cx) as well as dye or electrical coupling, were not detected in the different models of cultured neurons examined. Finally while CBX (at 100 μm) did not modify presynaptic transmitter release and postsynaptic responses to glutamate, it did cause an increase in the action potential threshold and strongly decreased the firing rate in response to a sustained depolarising current. These data demonstrate that CBX does not exert its action on network activity of cultured neurons through astrocytic GJs and suggest that it has direct effects on neurons, not involving GJs.

Spontaneous synchronised depolarisations, detectable in the form of burst firing or as intracellular calcium oscillations, reflect typical network activity that characterises neurons during normal physiological or pathological states. The mechanisms underlying synchronisation of neuronal activity are not entirely elucidated but several non-synaptic mechanisms, including electrical field effects, ionic changes in the extracellular space and electrical coupling through gap junctions channels (GJs) have been suggested (Dudek et al. 1999; McCormick & Contreras, 2001). Indeed, GJs provide the morphological basis for network organisation. They are formed by intercellular channels composed of 12 subunit proteins, called connexins (Cxs), which constitute a multigene family (Willecke et al. 2002) whose members are distinguished according to their molecular mass (Bruzzone et al. 1996). GJ permeability to ions and molecules with molecular masses of up to 1.2 kDa is controlled by several classes of endogenous and exogenous compounds including neurotransmitters, cytokines, growth factors (Rouach et al. 2002) and other bioactive substances, such as carbenoxolone (CBX), a potent GJ channel blocker, which is an aglycone of glycyrrhizic acid obtained from the licorice root Glycyrrhizia glabra (Rozental et al. 2001b). Neuronal GJs are proposed to play a crucial role in synchronised activity (Perez Velazquez & Carlen, 2000) since:(1) the presence of neuronal GJs has been demonstrated in slices of several brain structures (Connors et al. 1983; Lo Turco & Kriegstein, 1991; Yuste et al. 1995; Rorig et al. 1996; Venance et al. 2000); (2) neural network activity is abolished by GJ channel inhibitors in acute slices from different brain regions (Ishimatsu & Williams, 1996; Ross et al. 2000; Kohling et al. 2001; Margineanu & Klitgaard, 2001) and in culture (Fujita et al. 1998); (3) theoretical models of neuronal networks have suggested the importance of GJs in the synchronisation of neuronal ensembles (Perez Velazquez & Carlen, 2000); (4) finally, knockout mice for Cx36, the major Cx in interneurons, have impaired gamma oscillations (Hormuzdi et al. 2001; Buhl et al. 2003), high-frequency network oscillations (ripples) and 4-aminopyridine-induced epileptiform discharges in the hippocampus (Maier et al. 2002), and they were reported to lack synchrony in the inferior olive (Long et al. 2002). However, how electrical coupling between neurons can influence network activity is still an open question, especially as other types of network activity such as ultrafast (200–600 Hz) oscillations in the hippocampus (Buzsaki, 2001) and complex spike synchronisation in the inferior olive (Kistler et al. 2002) are still present in the Cx36 knockout mice. In addition, most uncoupling agents, extensively used in studies involving neuronal GJs in network activity, target different cell types connected through GJs and generally affect other ionic channels and receptors, as no natural toxin or specific inhibitor of GJs has been identified yet. In particular in the CNS, GJ channel inhibitors act on neurons but also on astrocytes, that is the major brain cell population coupled through GJs (Giaume & McCarthy, 1996; Spray et al. 1999).

Interestingly, astrocytes have been recently suggested to be required for the synchronous oscillatory and epileptiform activity of cultured hippocampal neurons (Verderio et al. 1999; Bacci et al. 2002). Indeed, astrocytes interact actively with neurons since they can sense and respond to synaptically released neurotransmitters with changes in intracellular calcium concentration, that in turn can affect synaptic transmission in culture (Araque et al. 1998a,b) or in slices (Kang et al. 1998). Spontaneous calcium oscillations in astrocytes have also been shown to drive neuronal excitation in situ through NMDA receptors (Parri et al. 2001). Furthermore astrocytic GJ communication and calcium wave propagation are regulated by neuronal activity (Rouach et al. 2000; Rouach & Giaume, 2001). Taken together, these data suggest a role for astrocytic GJ communication in neuronal network activity. However due to the lack of selective GJ blockers, in terms of the Cx and cell type targeted, it is not possible in situ to distinguish their site of action, either neurons or astrocytes.

The present study took advantage of pharmacological and molecular approaches in co-cultured neurons and astrocytes, where neurons display spontaneous synchronous activity and GJs are thought to be present primarily among astrocytes, to investigate the effect and potential site of action of the well-known GJ channel blocker, CBX, on neuronal network activity. We report here that CBX inhibits spontaneous and bicuculline-induced network activity as well as reducing excitability in neurons. However, these effects are not likely to be mediated by blockade of astrocytic or neuronal GJs.

METHODS

Tissue culture

All experimental procedures involving animals and their care were conducted in conformity with INSERM and Weizmann Institute guidelines.

Primary cultures of hippocampus were prepared from 19-day-old Wistar rat embryos as previously described (Papa et al. 1995). Briefly, pregnant females were killed by rapid cervical dislocation. The hippocampi were dissected, mechanically dissociated with a fire-polished Pasteur pipette and cells were resuspended (4 × 105 ml−1) in the plating medium composed of minimal essential medium (MEM)-Earl salts (Biological Industries), enriched with 0.6 % glucose, 20 μg ml−1 gentamicin, 2 mm glutamax and 10 % fetal calf serum (FCS). Cells were seeded on poly-ornithine-coated coverslips in 24-well plates and left to grow in the incubator at 37 °C, 5 % CO2. When cells reached confluency, after approximately 10 days in vitro (DIV), a mixture of 5′-fluoro-2-deoxyuridine and uridine (FUDR-U) (20 μg and 50 μg ml−1, respectively, Sigma) was used to block glial proliferation. After a few days, neurons were plated on astrocytes in a similar medium, replacing 5 % FCS with 5 % heat-inactivated horse serum (HS). Co-cultures of neurons and astrocytes were left to grow for 4 days. The medium was changed to 10 % HS in enriched MEM containing FUDR-U. Four days later, the medium was changed once again to 10 % HS in enriched MEM, and no further changes were made. Cultures were used during the second week in vitro.

A similar protocol was followed for mice cortical co-cultures, except that 16-day-old embryos were used and the medium was changed 24 h after neuronal plating for an enriched MEM medium containing FUDR-U. Partial medium changes were made twice a week.

To obtain rat hippocampal-enriched neuronal cultures, containing only a few scattered astrocytes, 1 × 105 cells ml−1 were resuspended in a serum-free medium consisting of MEM-Earl salts (Biological Industries) enriched with 0.6 % glucose, 20 μg ml−1 gentamicin, 2 mm glutamax and a mixture of salt and hormones containing insulin (25 μg ml−1), transferrin (100 μg ml−1), progesterone (20 nm), putrescine (60 μm) and sodium selenite (Na2SeO3, 30 nm). One day after plating, the cells were treated with FUDR-U. These cultures were used after 8–11 DIV.

Enriched neuronal cultures were also prepared from cerebral cortex of E16 mice. Cells were plated at 1.5 × 105 cells cm−2 on 35 mm dishes or 15 mm coverslips in 24-well plates. The culture medium consisted of MEM-Earl salts supplemented with 10 u ml−1 penicillin, 10 μg ml−1 streptomycin, 0.3 mg ml−1 glutamine, 0.6 % glucose, pyruvate 110 mg ml−1, 5 μg ml−1 insulin, 3 % HS and 1 % Ultroser-G and cells were treated with FUDR-U 1 day after plating.

Cx43-deficient and wild-type astrocytic cultures were prepared from the cortex of newborn Cx43-deficient mice (Reaume et al. 1995). Cells (4 × 105) were seeded on 35 mm dishes in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) containing 10 % FCS, 10 u ml−1 penicillin and 10 μg ml−1 streptomycin. The medium was changed twice a week. When cells reached confluency, after approximately 10 DIV, they were harvested with trypsin-EDTA and plated as secondary cultures in the same medium. After one week, AraC (10−5m) was added. Co-cultures were obtained by plating neurons on astrocytic monolayers as previously described. Cells were used for experiments during the second week of co-culture.

Immunocytochemistry

Cells were fixed at room temperature with either 2 % paraformaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature or acetone for 10 min at −20 °C (for Cx36 detection), washed several times with PBS and incubated for 1 h with PBS containing 10 % non-immune goat serum (Zymed, San Francisco, CA, USA) and 0.1 % Triton X-100. Cells were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibody against glial fibrillary acid protein (GFAP) (monoclonal mouse, 1/500, ICN) for astrocytes detection and microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2) (monoclonal mouse, 1/500, Sigma) for neuron detection. In addition, connexin immunostaining was performed in the same cultures using primary antibodies against Cx32 (polyclonal rabbit, 1/200, Zymed), Cx36 (polyclonal rabbit, 1/1000, Zymed) or Cx26 (monoclonal mouse, 1/200, Zymed). Secondary antibodies were applied in appropriate combinations for 1–2 h at room temperature and included TRITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (1/250, Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oregon, USA), FITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1/500, Southern Biotech, Birmingham, Alabama, USA). After staining, coverslips were mounted in Mowiol (Calbiochem) and examined with an upright microscope equipped with epifluorescence (Labophot, Nikon) or a confocal laser-scanning microscope (Zeiss 510 or Leica).

Determination of number of astrocytes

To determine the ratio of astrocytes/neuronsin enriched neuronal cultures, cells were doubly immunostained for GFAP and MAP2. Fluorescent labelling was examined under a microscope with the appropriate filters at a magnification of × 10. About 70 field images per coverslip were captured with a CCD camera connecting the microscope to the computer. In each field, the respective numbers of GFAP-positive and MAP2-positive cells were counted using an image analysis software (Lucia).

Electrophysiology

The cultures were transferred to the recording chamber and placed in a Zeiss Axioscope equipped with Nomarski optics, a water immersion objective and an infrared camera or an inverted Nikon microscope. Single or double whole-cell patch recordings from hippocampal neurons were performed at room temperature using micropipettes containing (mm): potassium gluconate 140, NaCl 2, Hepes 10, EGTA 0.2, Na-GTP 0.3, Mg-ATP 2, and phosphocreatine 10, pH 7.4, having a resistance in the range of 6–12 MΩ. In order to identify the recorded cell after immunocytochemistry and also for dye-coupling experiments, either LY or biocytin was added to the internal solution. Experiments were performed in the presence of a continuous perfusion at a rate of 1 ml min−1 at room temperature or in a static bath, except for the fast perfusion of CBX. Standard recording medium contained (mm): NaCl 129, KCl 4, MgCl2 1, CaCl2 2, glucose 10, and Hepes 10, pH was adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH, and osmolarity to 320 mosmol l−1 with sucrose. In some voltage-clamp experiments, QX314 (2 mm, Alomone Labs, Israel) was added to the recording pipette solution to block sodium channels and hence prevent unclamped action potentials. Current- and voltage-clamp recordings were performed using Axoclamp 2 and Axopatch amplifiers (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA, USA), respectively. Voltage-clamped neurons were held at −60 mV and signals were filtered at 5 kHz. Cells in current clamp were held at −60 mV. In experiments performed to test basic membrane properties, 0.5 μm tetrodotoxin (TTX) was added to the bath to block sodium channels in order to record miniature postsynaptic currents (mPSCs). To test electrical coupling between neurons, current clamp recordings were performed simultaneously in pairs of cells, using the double whole-cell recording technique. In this configuration, when the cells are connected by GJs, injection of a current step in one cell should be detected in the other cell. Signals were stored in a PC using Axon Instruments software. Data were analysed off-line using pCLAMP8 (Axon Instruments), Mini Analysis (Synaptosoft) and software written in Matlab (MathWorks). The threshold of an action potential was blindly and manually measured according to the highest change in the derivative of the potential. To evaluate the spontaneous synaptic activity of a cell, the mean current area (charge transfer) above a threshold was measured in a block of 15 s. The threshold was automatically calculated in Matlab according to the mean and standard deviation of the portion of trace not containing events. After the automatic detection every portion of the trace and its threshold were checked.

Determination of gap junctional dye coupling

Dye was injected into individual neurons or astrocytes during recording of the cell in the whole-cell configuration for at least 10 min with a patch pipette filled with Lucifer yellow (LY, 0.2 % dipotassium salt, Sigma Chemicals) or biocytin (0.2 %, Sigma). The pipette was then withdrawn and the microscopic field around the recorded cell was directly photographed under epifluorescence illumination when LY was used. For biocytin detection, cells were fixed in 2 % paraformaldehyde after pipette removal, washed and incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated streptavidin (Vector). After several washes, cells were mounted in Mowiol for microscopic examination. GJ communication between astrocytes was also studied using the scrape-loading technique, as previously described (Rouach et al. 2000). Experiments were performed by incubating cultures for 10 min in Hepes buffer solution (mm: NaCl 140, KCl 5.5, CaCl2 1.8, MgCl2 1, glucose 10 and Hepes 10, pH 7.3). Cells were then washed in a Ca2+-free Hepes solution, to prevent uncoupling of the cells during the scrape procedure, and loading was achieved with a razor blade in the same solution containing a dye (LY (0.1 % dilithium salt) or biocytin, 1 min). When pharmacological treatments were performed, tested compounds were present in all the solutions used. Astrocytic GJ communication was assessed 8 min after scraping. Cells were either processed for biocytin detection as described above or directly examined (for LY) with an inverted microscope (Diaphot, Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a camera where five successive photomicrographs per trial (Kodak TMAX, 400 ASA) were captured. Negatives were digitised and data were quantified by measuring diffusion of the dye between astrocytes by computation of the fluorescence areas (arbitrary unit, a.u.) in control and treated conditions with an image analyser system (NIH Image).

Calcium imaging

Measurements of [Ca2+]i in cultured rat hippocampal cells were made under single emission microfluorimetry using the cell-permeant fluorescent calcium probe, Fluo-4 AM (3 μm, Molecular Probes). The indicator was loaded into cells by incubation for 1 h at room temperature in a shaking bath containing the standard recording medium. Cells were transferred to the recording chamber of an upright microscope (Zeiss Axioscope) allowing continuous perfusion of solutions at a rate of 1 ml min−1 at room temperature. Fluo-4 was excited at 488 nm through a monochromator (Polychrome II, Till Photonics, Planegg, Germany) with integrated xenon lamp (75 W), controlled by the Axon Imaging Workbench software (AIW, Axon Instruments). Fluorescent emission of labelled cells at 510 nm was detected with a CCD camera (Sensicam, PCO). Images were taken through a 40 × 4 water immersion objective and stored on a PC. Cells were exposed to drugs either by a general perfusion system described above or by local pressure application through a micropipette. In the latter case, a pressure pipette with a tip diameter of 2 μm was placed 50–100 μm away from the cell and three consecutive 10 ms pressure pulses were applied at time intervals of 100 ms, using a programmable pulse generator (Master-8, AMPI, Jerusalem, Israel). When glutamate was applied, TTX (0.5 μm) was added into the external medium to pharmacologically isolate the cells. Off-line analysis of images was processed with AIW imaging software and software written in Matlab (MathWorks). Care was taken to avoid saturation of the dye or the detection system by staying away from the maxima for the fluorescence settings. Data are expressed as a change in fluorescence over baseline (ΔF/F0, %) and activity of cells was compared before and after perfusion with drugs. In some experiments, cell calcium imaging and electrophysiological recordings, in current-clamp mode were performed simultaneously.

Statistical analysis

When results from a single experiment were composed of different values (such as in the calcium imaging experiments or in the measurement of activity of a cell in voltage clamp), the Wilcoxon test was applied in each experiment for nonparametric statistical analysis to compare activity before and after a treatment, and the median of values was taken as a representative value for the experiment. Data were then expressed as means ±s.e.m. and n refers to the number of independent experiments. Mean statistical analysis was performed on raw data. Student's paired and unpaired t tests were used for comparison between two groups, while for multiple comparisons, ANOVA followed by post hoc Bonferroni's multiple comparison was performed. Statistical significance was established at *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01.

RESULTS

Astrocytic, but not neuronal or heterotypic gap junctions, are detected in co-cultures of neurons and astrocytes

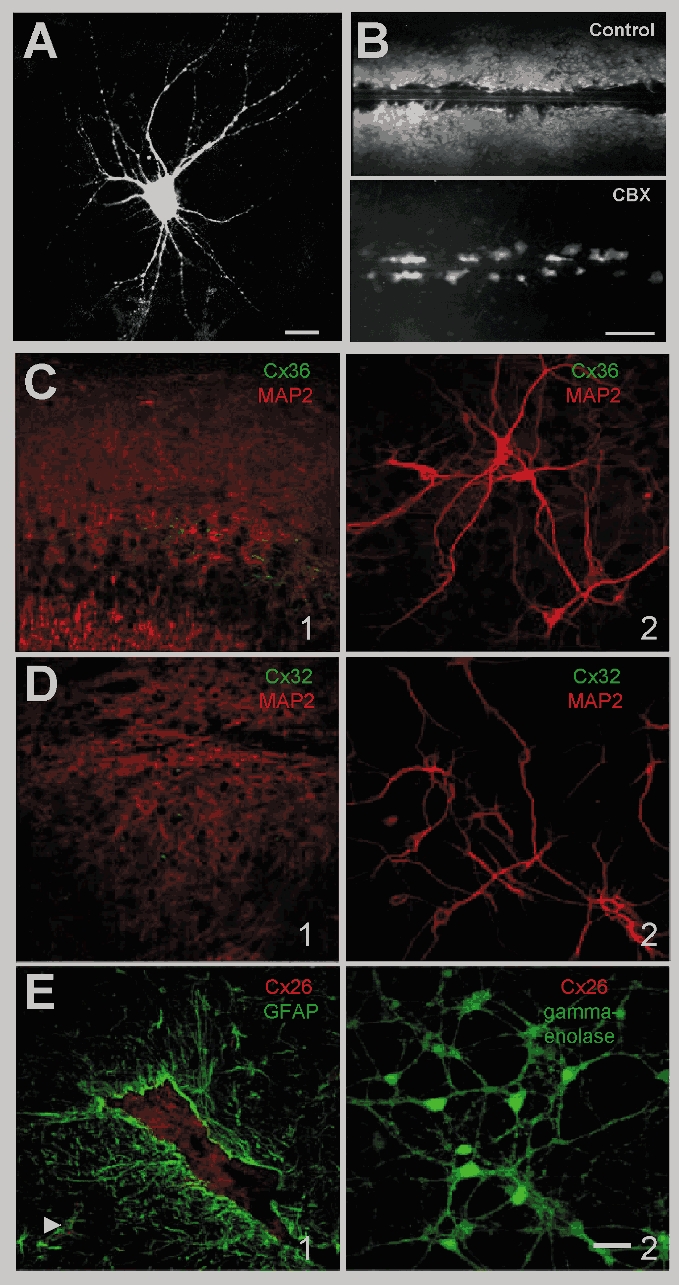

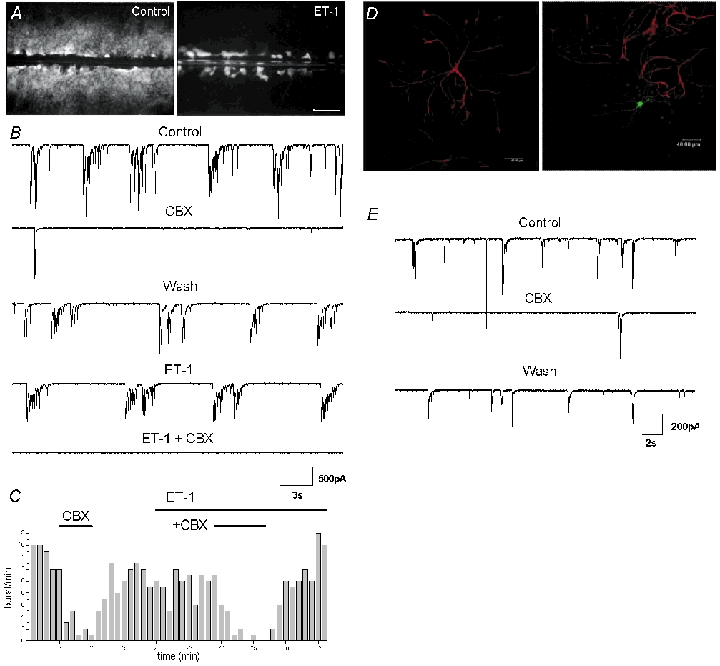

The existence and level of GJ communication were investigated in both neurons and astrocytes. A high level of astrocytic dye coupling was observed in hippocampal or cortical neuron-astrocyte co-cultures, as revealed by both patch-clamp and scrape-loading dye transfer techniques. Indeed, while LY loading of a single astrocyte with a patch-clamp pipette induced dye spread into more than 40 astrocytes, scrape-loading of astrocytes resulted in the staining of a large area covering several contiguous microscopic fields of astrocytes (fluorescence area: 32 ± 1.7 a. u., n = 3) (Fig. 1B). GJs between neurons, cultured for more than a week, were previously reported to be absent (Welsh & Reppert, 1996; Blanc et al. 1998; Fujita et al. 1998). The existence and functionality of GJ channels in neurons were further investigated in our co-cultures using dye coupling, electrical coupling and immmunostaining assays. Dye coupling between neurons or between neurons and astrocytes was never observed when single neurons were recorded with a patch-clamp pipette containing either LY, biocytin or calcein (LY, n = 12 and biocytin, n = 7, for calcein; E. Korkotian & M. Segal, unpublished observations) (Fig. 1A). To further explore possible electrical coupling among neurons, double whole-cell patch-clamp experiments were conducted. In none of the pairs studied was there any sign of electrotonic coupling (n = 8, data not shown). Finally, no specific staining for the three main neuronal Cxs (Cx26, Cx32 and Cx36) was detected in either enriched cultured neurons (data not shown) or neuron-astrocyte co-cultures, while labelled cells were detected in mouse brain sections (Fig. 1), as previously reported (Meier et al. 2002). Consequently, the existence of GJs and functional coupling was only detected between astrocytes but not neurons in our cultures; hence the use of GJ blockers in this model enables to assess the contribution of astrocytic GJ communication in their effect. While the most widely used GJ blocker, CBX, a derivative of glycyrrhetinic acid, has been shown to inhibit GJ channels in a variety of cells, we verified that it effectively inhibited GJ communication in our co-cultures. CBX (10–20-100 μm, 10 min) caused a rapid, and dose-dependent inhibition of astrocytic dye coupling, as assessed by the scrape-loading technique (−71 ± 4 %, n = 3, −85 ± 4 %, n = 3 and −92 ± 2 %, n = 3, respectively, P = 0.045, ANOVA test) (Fig. 1B). This effect was reversible within minutes after CBX removal (70 ± 6 % of control for CBX 100 μm, n = 3. Moreover, CBX (100 μm) also inhibited electrical coupling in pairs of astrocytes within 1 min of application in a reversible manner (W. Même, personal communication). In contrast, the CBX precursor glycyrrhizic acid (GZA) did not block GJs, when used at the same concentration (100 μm), n = 3. We then investigated the action of CBX on neuronal network activity.

Figure 1. Dye coupling and immunostaining of Cx in hippocampal co-cultures.

A, representative fluorescence micrograph of a neuron stained with LY in co-culture. Dialysis of LY was performed by patch-clamp recordings with a pipette solution containing 0.2 % LY. Calibration bar: 20 μm. No dye coupling was observed in neurons. B, representative fluorescence micrographs of LY spread between hippocampal astrocytes in the absence (Control) and presence of carbenoxolone (CBX, 100 μm, 10 min). The level of dye coupling between astrocytes was evaluated using the scrape-loading dye transfer technique and was totally prevented by CBX (100 μm, 10 min). Calibration bar: 250 μm. Immunofluorescent labelling of Cx36 (C), Cx32 (D) and Cx26 (E) in brain tissue and in neurons co-cultured with astrocytes for 14 DIV. C1, distribution of Cx36 immunoreactivity (green) in adult mouse brain section doubly labelled with anti-MAP2 (red). Note staining of hippocampal pyramidal cells is particularly bright in the proximal dendrites as well as the presence of some immunoreactive puncti in the cortex. This distribution is similar to the one described by Meier et al. (2002). although part of it was reported to be aspecific; C2, double staining of cultured neurons for Cx36 and MAP2 does not allow detection of Cx36 immunoreactive material in the extensive network of neurons brightly labeled with anti-MAP2. D1, distribution of Cx32 (green) in adult mouse brain section doubly labelled with anti-MAP2 (red) to detect neuronal dendrites. Note that small cell soma scattered in the grey matter are stained while processes are less visible as shown by Oguro et al. (2001). C2, Cx32 immunoreactivity (green) is not detectable in cultured neurons stained in red with anti-MAP2. E1, distribution of Cx26 (red) in an adult mouse brain section doubly labelled with anti-GFAP (green) to detect astrocytes in vivo. Note the labelling in the plexus choroid (GFAP-negative) and in astrocytes enwrapping blood vessels (arrow), reminiscent of Cx26 distribution previously reported in adult rat brain parenchyma (Mercier & Hatton, 2001); E2, Cx26 immunoreactivity (red) is not detectable in neurons doubly labelled with anti-gamma-enolase (green) to visualise the neuronal network. Similar results were obtained in enriched neuronal cultures (data not shown). Calibration bar: 40 μm.

Carbenoxolone strongly reduces neuronal spontaneous firing, synaptic activity and calcium oscillations in co-cultures of rat hippocampal neurons and astrocytes

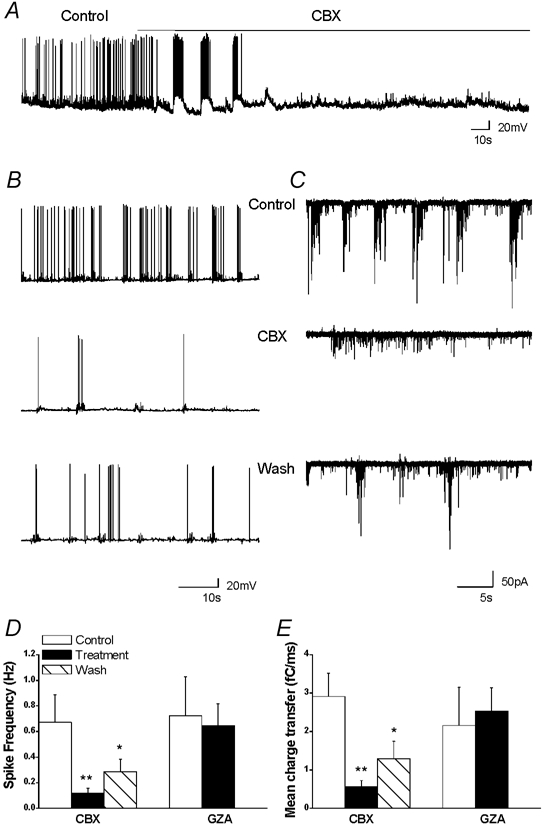

Rat hippocampal neurons cultured in the presence of astrocytes displayed spontaneous network activity consisting of mixed excitatory and inhibitory synaptic currents that developed over 12–15 DIV into individual events as well as coordinated rhythmic bursts of activity (Fig. 2C). CBX (100 μm, 10 min) strongly reduced spontaneous neuronal activity, measured as action potential frequency (from 0.67 ± 0.22 Hz to 0.12 ± 0.04 Hz, −82 ± 8 %, n = 9 and mean charge transfer (from 2.9 ± 0.61 fC ms−1 to 0.56 ± 0.17 fC ms−1, −81 ± 6 %, n = 14 (Fig. 2D and E). Bursting events completely disappeared in the presence of CBX and the activity became less organised, consisting of individual postsynaptic currents (PSCs). However CBX, during the first minute of its application, induced a high bursting activity that preceded the neurons’ silencing (Fig. 2A). After washout of CBX (10 min), the activity became again organised in bursts and action potential frequency and mean charge transfer showed a partial recovery (46 ± 16 %, n = 7, and 44 ± 11 %, n = 7, of control, respectively) (Fig. 2D and E). Similar results were obtained with a lower dose of CBX (20 μm, 10 min) (mean charge transfer decrease of −89 ± 2 %, n = 3, P = 0.004, ANOVA test), while intermediate effects were observed in the presence of 10 μm CBX (10 min), as action potential frequency and mean charge transfer were reduced by 62 ± 4 % n = 16 and 67 ± 8 % n = 14, respectively P = 0.038, ANOVA test). In contrast, application of glycyrrhizic acid (GZA, 100 μm, 10 min), did not affect spontaneous neuronal firing (90 ± 6 % of control, n = 5 (Fig. 2D) or mean charge transfer (117 ± 9 % of control, n = 6 (Fig. 2E).

Figure 2. Carbenoxolone strongly reduces neuronal spontaneous firing and synaptic activity in hippocampal co-cultures of neurons and astrocytes.

A–C, traces recorded in current clamp (A and B) and in voltage clamp (C) from neurons co-cultured with astrocytes in control condition (Control), during carbenoxolone application (100 μm, 10 min, CBX) and after wash (10 min, Wash). D and E, summary diagram of action potential frequency and mean charge transfer, which were used to quantify neuronal firing activity and spontaneous synaptic activity, respectively. During CBX treatment, both parameters were reduced, by 82 ± 8 % n = 9 and 81 ± 6 % n = 14, respectively. Application of glycyrrhizic acid (GZA, 100 μm, 10 min), a precursor of CBX, did not affect spontaneous activity n = 6. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 compared with control values (treatment/control and wash/treatment) (ANOVA followed by post hoc Bonferroni's multiple comparison (CBX) or Student's paired t test (GZA)).

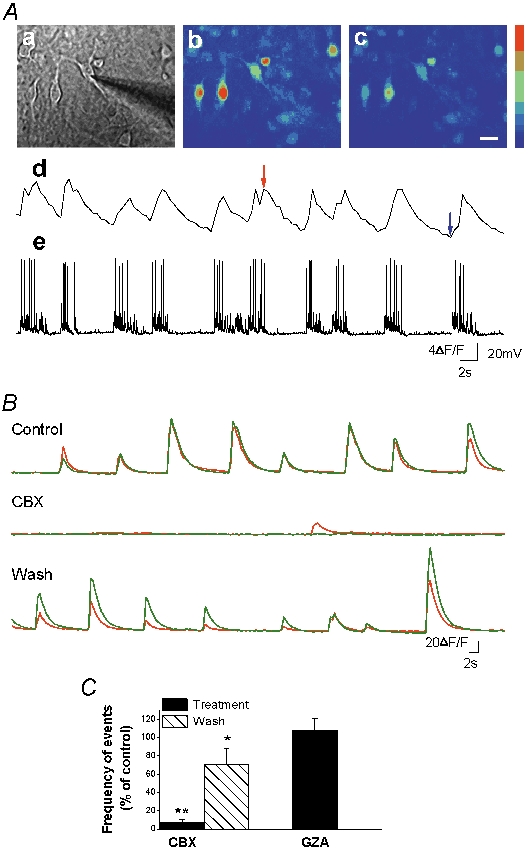

To determine the effect of CBX on synchronous neuronal activity, we used calcium imaging, which allows the monitoring of spontaneous activity in a population of cells. Simultaneous calcium imaging and whole-cell current-clamp recordings revealed the occurrence of spontaneous [Ca2+]i oscillations, correlated temporally with long bursts of closely associated action potentials (Fig. 3A). This activity occurred synchronously in neurons present in the same microscopic field (Fig. 3A) at an average frequency of 3.3 ± 0.3 min−1, and was mediated by activation of glutamate receptors, as it was abolished by the AMPA receptor antagonist NBQX (2,3-dioxo-6-nitro-1,2,3,4-tetrahydrobenzo[f]quinoxaline-7sulphonamide disodium; 5 μm, n = 3, data not shown). CBX (100 μm, 10 min) strongly diminished the mean frequency (−93 ± 4 %, n = 3, amplitude (−60 ± 4 %, n = 3 and decay time (−16 ± 3 %, n = 3 of calcium oscillations, without altering the basal [Ca2+]i levels in neurons (Tables 1 and 2). It also decreased correlation between cells (−73 ± 11 %, n = 3, although this effect was mostly due to the loss of the events. These effects of CBX were reversible within 10 min of washout. As observed with electrophysiological recordings, a lower dose of CBX (10 μm, 10 min) also induced a significant decrease in [Ca2+]i oscillation frequency (−42 ± 8 %, n = 3, P = 0.027, ANOVA test), although it did not significantly modify the amplitude or decay time of the events or correlation between cells (data not shown). In contrast, GZA (100 μm, 10 min) did not affect any parameter of these [Ca2+]i oscillations (Table 1, Fig. 3C).

Figure 3. Carbenoxolone strongly reduces neuronal spontaneous calcium oscillations in hippocampal cultures.

A, calcium imaging performed with Fluo-4 AM to monitor changes in [Ca2+]i from a cell population. Simultaneous patch clamp recording in current clamp (e) shows a tight correlation between membrane potential and [Ca2+]i oscillations (d). Aa, phase image of the field with the patch pipette. Ab and c, fluorescence images during high (red arrow) and low (blue arrow) calcium levels. Calibration bar (a–c), 10 μm; colour bar, 397–1887 (arbitrary fluorescence units, 12 bit resolution). B, calcium imaging recordings in two representative cells in control condition, during application of CBX (100 μm, 10 min) and after wash. C, summary diagram of event frequency showing that CBX application strongly reduced the oscillation frequency n = 3. Application of GZA did not affect neuronal [Ca2+]i oscillation frequency n = 3. For each experiment, changes in oscillation frequency induced by the treatment were normalised against the oscillation frequency obtained under control conditions. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 compared with control values (treatment/control and wash/treatment) (ANOVA followed by post hoc Bonferroni's multiple comparison (CBX) or Student's unpaired t test (GZA)).

Table 1.

Characteristics of neuronal spontaneous calcium oscillations in co-cultures

| Control | 100 μm CBX | Wash | Control | 100 μm GZA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency of events(min−1) | 3.3 ± 0.3(3) | 0.2 ± 0.1**(3) | 2.3 ± 0.6(3) | 3.1 ± 0.3(3) | 3.2 ± 0.1(3) |

| Baseline (F0) (a.u.) | 737 ± 44(3) | 773 ± 22(3) | 868 ± 87(3) | 786 ± 81(3) | 771 ± 51(3) |

| Peak normalised amplitude (ΔF/F0) | 42 ± 10(3) | 16 ± 2*(3) | 37 ± 0.14(3) | 56 ± 24(3) | 69 ± 23(3) |

| Decay time (s) | 2.44 ± 0.05(3) | 2.05 ± 0.04*(3) | 2.49 ± 0.16(3) | 2.85 ± 0.5(3) | 3 ± 0.2(3) |

| Coefficient of correlation | 0.86 ± 0.04(3) | 0.22 ± 0.08**(3) | 0.58 ± 0.27(3) | 0.87 ± 0.05(3) | 0.88 ± 0.05(3) |

Data are expressed as mean ±s.e.m. and are sampled from neurons recorded before (control), after perfusion with carbenoxolone (CBX, 100 μm, 10 min) and wash or after glycyrrhizic acid (GZA, 100 μm, 10 min). ANOVA followed by post hoc Bonferroni's multiple comparison(CBX) or Student's unpaired t test(GZA) were applied for statistical analysis

P < 0.05,

P < 0.01.

Numbers in parentheses are the number of independent experiments.

Table 2.

Characteristics of neuronal bicuculline-induced discharges in co-cultures

| Control | 100 μm CBX | Wash | Control | 100 μm GZA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency of events (min−1) | 2.1 ± 0.2(8) | 0.5 ± 0.2**(8) | 1.4 ± 0.3(5) | 2.0 ± 0.4(4) | 1.7 ± 0.2(4) |

| Baseline (F0) (a.u.) | 890 ± 109(8) | 954 ± 105(8) | 810 ± 101(5) | 875 ± 77(4) | 982 ± 109(4) |

| Peak normalised amplitude (ΔF/F0) | 126 ± 25(8) | 81 ± 28*(6) | 119 ± 37(5) | 191 ± 33(4) | 160 ± 80(4) |

| Decay time (s) | 4.87 ± 0.52(7) | 3.34 ± 0.35*(6) | 4.22 ± 0.21(4) | 5.45 ± 0.89(4) | 5.06 ± 0.3(4) |

| Coefficient of correlation | 0.96 ± 0.01(8) | 0.66 ± 0.09**(8) | 0.73 ± 0.1(5) | 0.98 ± 0.01(4) | 0.98 ± 0.01(4) |

Data are expressed as mean ±s.e.m. and are sampled from neurons recorded before (control), after perfusion with carbenoxolone (CBX, 100 μm, 10 min) and wash or after glycyrrhizic acid(GZA, 100 μm, 10 min). ANOVA followed by post hoc Bonferroni's multiple comparison (CBX) or Student's unpaired t test (GZA) were applied for statistical analysis

P < 0.05,

P < 0.01.

Numbers in parentheses are the number of independent experiments.

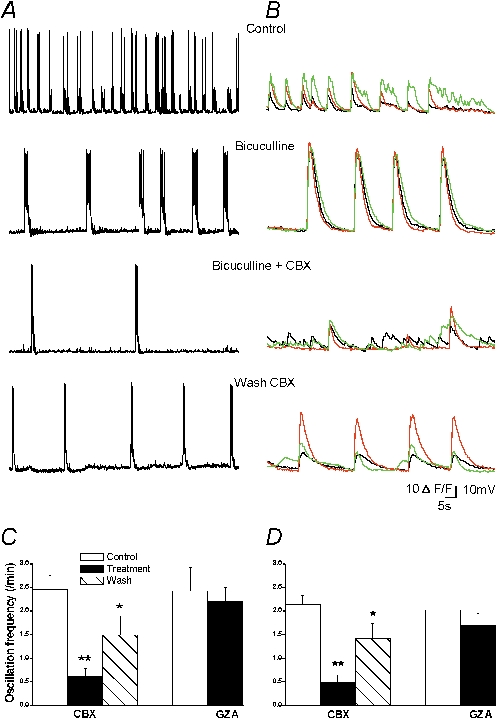

Carbenoxolone disrupts bicuculline-induced neuronal burst discharges in rat hippocampal co-cultures

Since CBX affected synchronous activity, we investigated whether it could also alter a more robust form of neuronal network activity, such as the one induced by the GABAA antagonist, bicuculline. Synchronous discharges appeared a few minutes after bicuculline (10 μm) application with a mean frequency of 2.5 ± 0.2 min−1 n = 18. Compared to spontaneous bursts, they were less frequent but more prolonged and associated with higher calcium increases (Tables 1 and 2), and, as for the spontaneous bursts, they were blocked by NBQX (5 μm, n = 4, data not shown). CBX (100 μm, 10 min) strongly reduced the frequency of the discharges in all neurons recorded either in current clamp (−62 ± 9 %, n = 8 cells,) or with calcium imaging (−78 ± 6 %, n = 8 experiments) (Fig. 4A and B). As observed for spontaneous activity, correlation between cells decreased in the presence of CBX (−30 ± 9 %, n = 8 and the remaining calcium bursts displayed a significant decrease in amplitude (−29 ± 7 %, n = 6 and decay time (−38 ± 9 %, n = 6 (Table 2). After CBX was washed out, the frequency of synchronised bursting recovered almost completely (92 ± 9 % of control, n = 5 cells in current clamp recordings; 78 ± 15 % of control in calcium imaging recordings, n = 5 experiments) (Fig. 4). As already observed for spontaneous network activity, a lower dose of CBX affected the discharges, while GZA (100 μm, 10 min) had no effect (Table 2). Indeed, 10 μm CBX (10 min) decreased calcium burst frequency (−64 ± 11 %, n = 3 experiments, P = 0.004), event amplitude (−49 ± 12 %, n = 3, P = 0.025), and decay time (−22 ± 8 %, n = 3, P = 0.04; Student's unpaired t test applied for all parameters). These findings show that CBX blocks the oscillatory firing of the excitatory network induced by bicuculline.

Figure 4. Carbenoxolone disrupts neuronal bicuculline-induced discharges in hippocampal co-cultures.

A and B, bicuculline application (10 μm) induced neuronal synchronous epileptiform discharges in current clamp (A) and calcium recordings (B) in two separate experiments. Application of CBX (100 μm, 10 min) reduced neuronal discharges frequency, duration (current clamp) and amplitude (calcium signal); C and D, summary diagram of neuronal bicuculline-induced discharge mean frequency, during application of CBX and after wash in current clamp (n = 8 cells; C) and calcium recordings (n = 8 experiments; D). Application of the GZA did not affect the discharge frequency in current clamp (n = 5 cells) and calcium recordings (n = 4 experiments). *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 compared with control values (treatment/control and wash/treatment) (ANOVA followed by post hoc Bonferroni's multiple comparison (CBX) or Student's paired t test (GZA)).

Carbenoxolone effect on neuronal activity is not mediated by inhibition of astrocytic gap junctions

We have shown that CBX rapidly and reversibly abolished neuronal network activity. To test whether the effect of CBX was mediated by blockade of astrocytic intercellular communication, CBX was applied onto three different models of mice cortical cultures, in which astrocytic GJ channels were not functional or lacking. As described above for rat hippocampal co-cultures, neurons from mice cortical co-cultures displayed spontaneous network activity that was abolished by CBX.

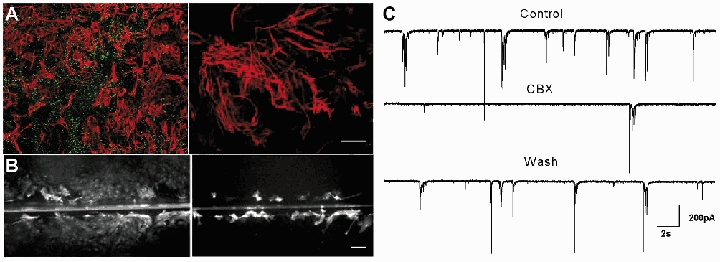

In one series of experiments the effect of endothelin-1 (ET-1), a peptide known to inhibit GJ channels in astrocytes (Giaume et al. 1992), was investigated. As with CBX, ET-1 (200 nm, 10 min) inhibited GJ communication in astrocytes assessed by the scrape-loading technique (−92 ± 2 %, n = 3, P = 0.001, Student's unpaired t test; Fig. 5A). However, ET-1 neither mimicked nor occluded the effect of CBX on neuronal network activity in co-cultures (Fig. 5B and C). Indeed the frequency of synaptic current bursts was not affected by ET-1 (200 nm, 10 min) (11.6 ± 1.6 in control vs. 11.3 ± 1.5 min−1 after ET-1 application, n = 4) while it was drastically and reversibly reduced by CBX (20 μm, 5 min) applied either in the absence of ET-1 (from 12.2 ± 0.9 min−1 in control to 0.8 ± 0.2 min−1, n = 5, P = 0.001, ANOVA test) or in the presence of ET-1 (to 0.6 ± 0.2 min−1, n = 5, P < 0.01, ANOVA test). Also the recovery after CBX wash was similar (9.0 ± 1.8 min−1 (n = 5), and 9.1 ± 1.5 min−1 (n = 4), in the absence and presence of ET-1 respectively).

Figure 5. Carbenoxolone still exerts its action in co-cultures, where astrocytic GJs are pharmacologically blocked, and in enriched neuronal cultures.

A, endothelin-1 inhibits dye coupling between mouse cortical astrocytes in co-cultures, assessed by the scrape-loading dye transfer technique; representative fluorescence micrographs of LY spread between astrocytes in the absence (Control) and presence of endothelin (ET-1, 100 nm, 10 min). Calibration bar: 250 μm. B and C, endothelin-1 does not mimic or occlude the effect of CBX. B, traces recorded in voltage clamp from the same neuron in co-cultures from mouse cortex. ET-1 (200 nm) does not alter neuronal activity and does not prevent the effect of CBX (20 μm, 5 min), although the dose is sufficient to block GJs in astrocytes. C, burst frequency of the neuron shown in A plotted against time. Each bar represents the number of bursts recorded during 1 min. C and D, carbenoxolone reduces burst activity in enriched neuronal culture. D, double labelling for GFAP (red) and biocytin (green) in enriched neuronal culture shows that in this model few isolated astrocytes are present. Calibration bars: 40 μm. E, traces recorded in the biocytin-injected neuron shown in D during control, CBX (20 μm) application and after wash.

In another set of experiments the effect of CBX was assessed in enriched neuronal cultures. In this model, only few astrocytes were present, since their proliferation was prevented by application of FUDR-U 24 h after neuronal plating. Indeed, the ratio of astrocytes/neuronswas less than 1 % (on 72 ± 2 fields counted per coverslip, 25 ± 10 did contain astrocytes (n = 3) and 2 ± 0.16 astrocytes for 138.96 ± 9.77 neurons were counted in the fields containing astrocytes). The few astrocytes present displayed a different morphology as they were bigger and remained mainly isolated (Fig. 5D). In this type of cultures, neurons displayed shorter and more frequent bursts of spontaneous synaptic activity (13.9 ± 1.0 min−1) (Fig. 5). However CBX did still reversibly reduce the burst frequency to 3.9 ± 0.2 min−1 (27.8 ± 6 % of control, n = 4, P = 0.023, ANOVA test), although its effect was less prominent than in co-cultures (Fig. 5E).

Finally the activity of neurons from wild-type mice plated on astrocytes originating from either wild-type or knockout mice for Cx43, the major Cx expressed in astrocytes, was compared. In co-cultures of wild-type neurons plated on Cx43 knockout astrocytes, Cx43 was not expressed as revealed by the lack of immunostaining with Cx43 antibodies (Fig. 6A right) and astrocytic dye coupling was not detectable as assessed by the scrape-loading technique, using either LY or biocytin as intracellular tracer molecules (Fig. 6B right): indeed, in all the samples tested, dye diffusion (0 ± 0 % of control, n = 4) to an astrocyte not directly involved in the scrape-loading was never observed, in contrast with the large dye spread occurring in cultures obtained from Cx43-expressing astrocytes obtained from the same littermate (control, n = 4) (Fig. 6B). However in co-cultures of wild-type neurons plated on Cx43 knockout astrocytes, both types of network activities, spontaneous (Fig. 6C) and bicuculline-induced (data not shown), were still present. This indicates that gap junctional communication in astrocytes was not essential for this kind of activity. Moreover, CBX (20 μm) did still reversibly reduce the frequency of spontaneous bursts (10.3 ± 2.4 min−1 in control, 1.1 ± 0.2 min−1 after CBX application and 9.1 ± 1.5 min−1 after CBX wash, n = 4, P = 0.026, ANOVA test). These data show that Cx43, the major GJ channel-forming protein in cultured astrocytes, is not involved in the generation of neuronal network activity.

Figure 6. Carbenoxolone reduces burst activity in co-cultures containing astrocytes from Cx43 knockout mice.

A, double labelling for GFAP (red) and Cx43 (green) in astrocytes cultured from wild-type (left) and Cx43 (−/−) mice (right). Calibration bar: 80 μm. B, dye coupling of astrocytes in wild-type (left) and Cx43 (−/−) mice (right). In wild-type cultures, Lucifer yellow taken up by the cells involved in the scrape is transferred to other cells through GJ channels. In contrast, in astrocytes from Cx43-deficient mice, only the cells involved in the scrape are stained. Calibration bar: 100 μm. C, traces recorded in voltage clamp in wild-type neuron co-cultured with astrocytes from the Cx43 (−/−) mice. Burst activity was still present and CBX (20 μm, 10 min) strongly reduced it despite the absence of Cx43 and astrocytic coupling.

Carbenoxolone does not modify presynaptic transmitter release and postsynaptic responses to glutamate

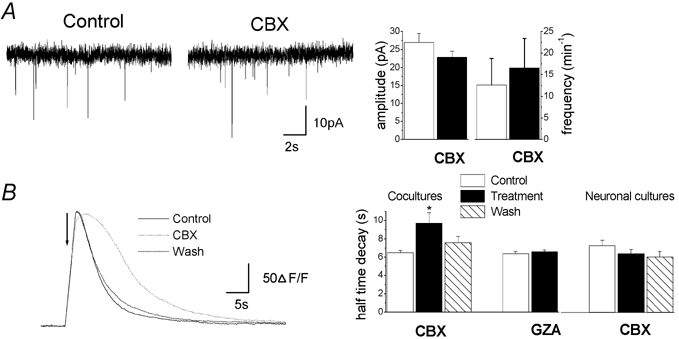

We further investigated whether CBX had any effect on neuronal properties involved in bursting activity in rat hippocampal co-cultures. To determine whether CBX modified basic properties of synapses, mPSCs were recorded in the presence of TTX (0.5 μm), to block action potentials. No significant difference was found during CBX application (100 μm, 10 min) in mPSCs frequency (12.6 ± 6.2 min−1 in control vs. 16.6 ± 6.8 min−1 after CBX application, n = 14), amplitude (27 ± 2.5 pA in control vs. 22.8 ± 1.7 after CBX application, n = 14) or decay time (2.7 ± 0.2 ms in control vs. 2.5 ± 0.2 ms after CBX application, n = 14; P > 0.05, Student's paired t test applied for all parameters) (Fig. 7A). These data indicate that CBX does not affect basic properties of synaptic transmission in these neurons.

Figure 7. Carbenoxolone does not modify presynaptic transmitter release and postsynaptic responses to glutamate.

A, miniature excitatory and inhibitory postsynaptic currents (mPSCs) in the presence of TTX (0.5 μm) from a representative neuron in co-culture showing that CBX had no effect on neurotransmitter release. Right: summary diagram of mPSCs mean amplitude and frequency before and during CBX application (n = 14, P > 0.05, Student's paired t test). B, neuronal calcium responses to focal glutamate application (indicated by the arrow, 500 μm, TTX 0.5 μm) from a representative neuron loaded with Fluo-4 in co-cultures in control conditions (Control), during application of CBX (100 μm, 10 min) and after wash. Similar observations were observed from 202 neurons recorded from four independent experiments. Right: summary diagram of calcium response half-decay time showing that CBX application increased the half-decay time in co-cultures (n = 4) but not in neuronal cultures (n = 5). *P < 0.05 compared with control values (treatment/control and wash/treatment) (ANOVA followed by post hoc Bonferroni's multiple comparison (CBX) or Student's unpaired t test (GZA)).

We also examined whether CBX impaired glutamate postsynaptic responses in neurons. For this purpose, neuronal calcium responses to l-glutamate puffs were measured in the presence of TTX (0.5 μm). CBX (100 μm, 10 min), like GZA (100 μm, 10 min), did not affect basal intracellular calcium concentration ([Ca2+]i) nor the amplitude or rise time of neuronal responses to pressure-applied glutamate (500 μm) (Table 3, Fig. 7B). However CBX induced a significant increase in half-decay time (6.6 ± 0.2 s in control vs. 9.7 ± 1.1 s after CBX application, n = 4), while GZA had no effect (Table 3, Fig. 7). The effect of CBX on decay time was probably mediated by astrocytes since neuronal responses to glutamate were not affected by CBX in enriched neuronal cultures, containing few astrocytes (Table 3). Altogether, these data suggest that CBX does not act directly on the functionality of postsynaptic glutamate receptors.

Table 3.

Glutamate-induced calcium responses in neurons

| Co-cultures | Control | 100 μm CBX | Wash | Control | 100 μm GZA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (F0) (a.u.) | 899 ± 45 | 971 ± 46 | 921 ± 76 | 870 ± 32 | 848 ± 36 |

| Peak normalised amplitude (ΔF/F0) | 190 ± 20 | 180 ± 20 | 160 ± 10 | 220 ± 10 | 230 ± 10 |

| Rise time (s) | 1.48 ± 0.16 | 1.57 ± 0.11 | 1.38 ± 0.17 | 0.98 ± 0.12 | 1.08 ± 0.13 |

| Half-decay time (s) | 6.48 ± 0.25 | 9.69 ± 1.18** | 7.55 ± 0.68 | 6.38 ± 0.22 | 6.58 ± 0.20 |

| Enriched neuronal cultures | Control | 100 μm CBX | Wash | ||

| Baseline (F0) (a.u.) | 810 ± 28 | 808 ± 32 | 802 ± 28 | ||

| Peak normalised amplitude (ΔF/F0) | 200 ± 10 | 190 ± 10 | 180 ± 10 | ||

| Rise time (s) | 0.79 ± 0.05 | 0.80 ± 0.05 | 0.76 ± 0.07 | ||

| Half-decay time (s) | 7.25 ± 0.58 | 6.38 ± 0.46 | 6.03 ± 0.61 | ||

Data are expressed as mean ±s.e.m. and were obtained from 4 and 5 independent experiments in co-cultures and enriched neuronal cultures, respectively. Neurons were recorded before (control), after perfusion with carbenoxolone (CBX, 100 μm, 10 min) and wash or after glycyrrhizic acid (GZA, 100 μm, 10 min). ANOVA followed by post hoc Bonferroni's multiple comparison (CBX) or Student's unpaired t test (GZA) were applied for statistical analysis

P < 0.01.

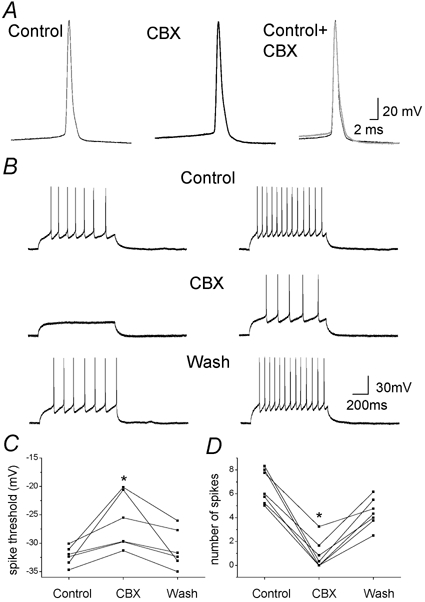

Carbenoxolone modifies intrinsic properties and excitability of neurons

Finally, potential effects of CBX on intrinsic neuronal properties and excitability were analysed. While CBX (100 μm, 10 min) had no effect on mean resting membrane potential, although cell recordings became less stable, it significantly and reversibly decreased neurons’ input resistance in six out of eight cells (−38 ± 9 %) (Table 4). In addition, when used at this concentration, CBX had a drastic effect on neuronal excitability. Action potential threshold was reversibly increased (+23 ± 6 %, n = 7) (Table 4), and the number of action potentials elicited by depolarising current pulses (1 s from a holding potential of −60 mV) was strongly decreased (−87.2 ± 6.3 %, n = 7) (Fig. 8, Table 4). The effects on input resistance and excitability seem to be independent since a decrease in excitability was observed even in the absence of change in input resistance. In contrast, GZA (100 μm, 10 min, n = 4) or a lower dose of CBX (20 μm, 10 min, n = 7), that blocked network activity, had no effect on neuronal excitability. Indeed the action potential threshold was-5.4 ± 2.0 mV in control versus−37.1 ± 1.4 mV during 20 μm CBX application (n = 8), while the number of spikes elicited from step current were 6.4 ± 0.7 and 6.1 ± 0.6 in control and during CBX application (n = 5; P > 0.05, Student's paired t test for both parameters), respectively. These observations indicate that at least for high doses, CBX has a direct effect on intrinsic properties and neuronal excitability.

Table 4.

Basic membrane properties and action potential characteristics in neurons

| Control | 100 μm CBX | Wash | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resting membrane potential (mV) | −58.9 ± 2.2 | −58.4 ± 3.1 | −59.2 ± 2.7(12) |

| Input resistance (MΩ) | 348.5 ± 100.6 | 186.5 ± 44.3* | 298.8 ± 63.2(6) |

| AP amplitude (mV) | 82.8 ± 5 | 83 ± 6 | 82.3 ± 6(7) |

| AP threshold (mV) | −30.4 ± 1.9 | −23.8 ± 2.9* | −29.3 ± 2.1(7) |

| Elicited AP s−1 | 6.6 ± 0.5 | 0.8 ± 0.5** | 4.4 ± 0.5(7) |

Data are expressed as mean ±s.e.m. and are sampled from neurons recorded before (Control), after perfusion with carbenoxolone (CBX, 100 μm, 10 min) and after CBX wash (Wash, 10 min). ANOVA followed by post hoc Bonferroni's multiple comparison was applied for statistical analysis

P < 0.05,

P < 0.01.

Numbers in parentheses are the number of cells. AP, action potential.

Figure 8. Neuronal intrinsic properties and excitability are altered by carbenoxolone.

A, individual and superimposed traces of action potential recorded from a representative neuron in hippocampal co-culture in control and during CBX application. B, action potentials elicited by two different current pulses (1 s duration; left, 30 pA; right, 40 pA) from a holding potential of −60 mV from a representative neuron in control, during application of CBX (100 μm, 10 min) and after wash when GABAergic and glutamatergic synaptic transmission were inhibited by bicuculline (5 μm), DNQX (10 μm) and APV (20 μm). C and D, plot of the mean number of evoked action potentials (C) and action potential threshold (D) before and during CBX application, and after wash for each neuron (n = 6> and n = 7, respectively, *P < 0.05, ANOVA followed by post hoc Bonferroni's multiple comparison).

DISCUSSION

To assess the effect and identify the site of action of the GJ blocker CBX on neuronal activity, we used in vitro models of hippocampal and cortical co-cultures, where only astrocytes are found to be connected through GJs and to express Cxs. Using both pharmacological and molecular approaches to disrupt GJ communication, this study provides several lines of evidence indicating that CBX alteration of neuronal network activity is not mediated by blockade of astrocytic GJs and is unlikely to be related to neuronal GJs either. Indeed, neuronal Cxs or functional coupling between neurons were not detected in these cultures. Moreover, spontaneous and bicuculline-induced network activity occurred in neurons co-cultured with either Cx43 knockout astrocytes or less than 1 % of isolated astrocytes. Finally, CBX altered intrinsic neuronal properties and excitability, suggesting that CBX may exert its action through direct mechanisms other than GJs.

Astrocytic gap junctions are not involved in neuronal network activity in co-culture

Recent experimental evidence presented by several laboratories suggests that neurons and astrocytes function as interdependent networks that have established a close bi-directional communication (Fields & Stevens-Graham, 2002). However, an important finding of this study is that astrocytic GJs are not involved in neuronal network activity in co-culture, since: (1) ET-1, a peptide that inhibited GJs in astrocytes, did not mimic or occlude the effect of CBX on network activity in co-cultures; (2) in enriched neuronal cultures, containing less than 1 % of isolated astrocytes, neurons displayed bursts of spontaneous synaptic activity and CBX did still reversibly reduce the burst frequency; (3) in co-cultures of wild-type neurons plated on Cx43 knockout astrocytes, burst activity, whether spontaneous or bicuculline-induced, was still present and CBX did still reversibly reduce the frequency of spontaneous bursts.

The present conclusion that astrocytic GJs are not involved in neuronal network activity, differs from the one proposed in a pharmacological study performed on rat cortical co-cultures (Fujita et al. 1998), although the primary observations were identical. Indeed since it was also observed that GJ blockade inhibited neuronal spontaneous calcium oscillations and dye coupling was absent in neurons, GJ blockers were believed to exert their effect via astrocytic GJs (Fujita et al. 1998). However, the use of combined pharmacological and molecular approaches, to specifically disrupt astrocytic GJ communication, clearly demonstrates that CBX can still exert its effect when astrocytic GJs are non-functional (ET-1) or absent (Cx43 knockout mice). In addition, by showing that neuronal network activity is still present in co-cultures of wild-type neurons plated on Cx43 knockout astrocytes, our data extend previous observations made in organotypic brain slice cultures from embryonic Cx43 knockout mice (Perez Velazquez et al. 1996), in which neuronal development assessed morphologically and electrophysiologically appeared normal. Altogether, these data demonstrate that although astrocytes have been shown to modulate neurotransmission (Araque et al. 1998a,b; Verderio et al. 1999; Parri et al. 2001; Bacci et al. 2002), their intercellular communication is not essential for neuronal network activity in co-culture.

Carbenoxolone blockade of neuronal network activity may not involve neuronal gap junction channels in co-culture

A number of reports have shown that GJ blockers, such as CBX, inhibit several kinds of neuronal network activity, driven by excitatory (Ishimatsu & Williams, 1996; de Curtis et al. 1998; Ross et al. 2000; Kohling et al. 2001; Margineanu & Klitgaard, 2001) as well as inhibitory inputs (Yang & Michelson, 2001), in acute slices from different areas of the brain. These studies suggested a prominent role for neuronal GJs in the synchronisation of epileptiform activity (Perez Velazquez & Carlen, 2000; Traub et al. 2002). This is supported by the presence of GJs between neurons, which has been demonstrated in slices of the developing cortex (Connors et al. 1983; Lo Turco & Kriegstein, 1991; Yuste et al. 1995; Rorig et al. 1996; Venance et al. 2000) and adult cortex (Galarreta & Hestrin, 2002; Meyer et al. 2002), as well as in defined areas of juvenile and adult brain (inferior olive, retina, olfactory bulb, locus coeruleus, hippocampus) (Bennett, 2000; Rash et al. 2000; Venance et al. 2000; Devor & Yarom, 2002; Meyer et al. 2002). However, in most areas of the CNS, the number of neuron to neuron GJs was found to be low, compared to the ones between astrocytes (Sotelo & Korn, 1978; Venance et al. 2000; Rash et al. 2001). Heterotypic coupling between astrocytes and neurons has also been recently described in young embryonic co-cultures (24 to 72 hours) (Froes et al. 1999) and in acute brain slices of locus coeruleus (Alvarez-Maubecin et al. 2000) or developing cortex (Bittman et al. 2002), but no ultrastructural evidence of such coupling was found in the adult rat brain (Rash et al. 2001). In hippocampal and cortical neuron-astrocyte co-cultures used in this study, GJ channels in neurons were not detected, using three different assays: dye coupling, electrical coupling and immmunostaining for three major neuronal Cxs (Cx26, Cx32 and Cx36). In addition, no heterotypic coupling between neurons and astrocytes, investigated by dye coupling experiments, was found, suggesting that astrocytes are the only population highly coupled by GJ in our co-cultures. These data are in agreement with several studies performed in co-cultures from either the hippocampus (Blanc et al. 1998), cortex (Fujita et al. 1998) or suprachiasmatic nucleus (Welsh & Reppert, 1996). Indeed GJs between embryonic neurons, cultured for more than a week, are usually reported to be absent, except for dopaminergic midbrain neurons (Leung et al. 2001) and fetal human hippocampal neurons (Rozental et al. 2001a). Therefore, CBX is not likely to inhibit neuronal network activity by acting on neuronal GJs in co-cultures. However we cannot totally rule out the expression of other neuronal Cxs (although we tested the major ones), or a very low level of dye or ionic coupling between neurons, as recently described for pyramidal cells from CA1 and CA3 hippocampal slices (Kohling et al. 2001; Margineanu & Klitgaard, 2001; Schmitz et al. 2001), that could not be detected by our assays. Nevertheless our findings strongly suggest that CBX exerts its action on cultured neurons through direct mechanisms other than GJs.

Multiple sites of action of carbenoxolone

In contrast to most ionic channels, no natural toxin or specific inhibitor of GJs has been identified yet and most uncoupling agents generally affect other ionic channels and receptors. For instance, some GJ blockers (octanol, halothane) interfere directly with excitatory synaptic transmission (Puil & el-Beheiry, 1990; Puil et al. 1990; Pocock & Richards, 1993; Rorig et al. 1996) or block spontaneous neuronal firing and decrease spike amplitudes (halothane) (Travagli et al. 1995). Up to now, CBX was commonly used to block GJs, since it was believed to be devoid of major side effects, although the literature is controversial. CBX has been reported to have no effect on evoked synaptic responses (Ishimatsu & Williams, 1996; Ross et al. 2000; Kohling et al. 2001), postsynaptic responses to neurotransmitters such as GABA (GABAB receptor-mediated) (Yang & Michelson, 2001), intrinsic neuronal properties (Travagli et al. 1995; Osborne & Williams, 1996; Kohling et al. 2001; Schmitz et al. 2001; Yang & Michelson, 2001), neuronal excitability (Kohling et al. 2001; Margineanu & Klitgaard, 2001; Schmitz et al. 2001) and cell conductances (Travagli et al. 1995; Osborne & Williams, 1996). Conversely, substantial effects of CBX on neuronal membrane properties have been described in respiratory neurons of the pre-Bötzinger complex, where the input resistance and firing properties were reversibly reduced by CBX application (Rekling et al. 2000). Moreover effects of CBX on antidromic responses of CA3 pyramidal cells have been found (Gladwell & Jefferys, 2001), but these results were interpreted as evidence supporting the prediction of a low incidence of GJs between pyramidal cell axons, rather than on the excitability of the neurons themselves.

An important finding of the present study is that the effects of CBX on cultured neurons are unlikely to be mediated by GJ block. Indeed, while CBX did not modify presynaptic transmitter release and postsynaptic responses to glutamate, it altered intrinsic neuronal properties, increasing the action potential threshold and decreasing the input resistance and firing rate in response to depolarising stimuli. In particular, two specific effects of CBX identified in this study, the high bursting activity induced during the first minute of CBX application and the decrease in input resistance, cannot be the consequences of GJ blockage. However these effects of CBX on cultured neurons may not necessarily be present in acute slices or in vivo, as under the latter experimental conditions, membrane currents may respond differently to CBX. Identification of other potential targets of CBX, and in particular ionic conductances, will require further investigation. Preliminary results suggest direct effects of CBX on K+ channels, since disappearance of the typical sag associated with hyperpolarising pulses was often observed. Furthermore dramatic side effects of CBX are also suggested by the massive neuronal death induced by long exposure (24 h) of cultures at low doses of CBX (10 μm) (N. Rouach & A. Koulakoff, unpublished observations).

However, several already known targets of CBX can be considered with respect to their potential effect on neuronal network activity. Indeed, although CBX is known to be a mineralocorticoid agonist, the use of spironolactone, a mineralocorticosteroid antagonist, does not alter the ability of CBX to depress spontaneous epileptiform activity in hippocampal slices (Ross et al. 2000). CBX, like other glycyrrhizin derivatives, has also been shown to inhibit the Na+-K+-ATPase (Zhou et al. 1996). However since partial inhibition of Na+-K+-ATPase reversibly induces neuronal epileptiform bursting activity in the rat CA1 hippocampus (Vaillend et al. 2002), it is unlikely that this effect mediates CBX blockade of network activity, although we speculate that it may account for the increase in bursting activity observed during the initial phase of CBX application. Finally, 18-β-glycyrrhetinic acid (βGA, 40 μm), from which CBX is synthetically derived, completely blocked the Cl− conductances in confluent primary cultures of rat hepatocytes, while leaving Na+ and K+ conductances intact (Bohmer et al. 2001). This is of particular interest, as it has been shown that a chloride conductance participates in the subthreshold behaviour and membrane potential of rat sympathetic neurons and may possibly control neuronal excitability (Sacchi et al. 1999). Alternatively, potential effects of CBX on K+ and Ca2+ conductances, may mediate CBX alteration of neuronal network activity.

The role of GJs in synchronisation of neuronal activity is still debated. In fact, how low coupling can affect so dramatically a network remains an open question. Indeed, the lack of the neuronal Cx36 in transgenic knockout mice does not affect ultrafast (200–600 Hz) oscillations in the hippocampus (Buzsaki, 2001) and complex spike synchronisation as well as normal motor performance in the inferior olive (Kistler et al. 2002). In addition the importance of GJs in neuronal oscillatory activity differs according to the theoretical model of interneuron network used (Bartos et al. 2001; Traub et al. 2001). Although our data do not exclude a role for neuronal GJs in network activity in other experimental models, such as acute brain slices, where functional neuronal GJs have been clearly demonstrated, they strongly suggest that caution should prevail when using CBX as a specific GJ blocker. More generally, they question the specificity of most GJ blockers extensively used in studies to examine the involvement of GJs in neuronal network activity. Thus direct evidence for a possible role of GJs still awaits the development of specific GJ blockers that do not otherwise affect neuronal excitability.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank V. Greenberger for providing cell cultures, E. Korkotian and M. Goldin, for help with confocal microscopy. This work was in part supported by the European Community grant no. QLK6-CT-1999-02203. N. R. was supported by FEBS and E. A. by INSERM (Poste Vert).

REFERENCES

- Alvarez-Maubecin V, Garcia-Hernandez F, Williams JT, Van Bockstaele EJ. Functional coupling between neurons and glia. J Neurosci. 2000;20:4091–4098. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-11-04091.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araque A, Parpura V, Sanzgiri RP, Haydon PG. Glutamate-dependent astrocyte modulation of synaptic transmission between cultured hippocampal neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 1998a;10:2129–2142. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araque A, Sanzgiri RP, Parpura V, Haydon PG. Calcium elevation in astrocytes causes an NMDA receptor-dependent increase in the frequency of miniature synaptic currents in cultured hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 1998b;18:6822–6829. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-17-06822.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacci A, Sancini G, Verderio C, Armano S, Pravettoni E, Fesce R, Franceschetti S, Matteoli M. Block of glutamate-glutamine cycle between astrocytes and neurons inhibits epileptiform activity in hippocampus. J Neurophysiol. 2002;88:2302–2310. doi: 10.1152/jn.00665.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartos M, Vida I, Frotscher M, Geiger JR, Jonas P. Rapid signaling at inhibitory synapses in a dentate gyrus interneuron network. J Neurosci. 2001;21:2687–2698. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-08-02687.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett MV. Seeing is relieving: electrical synapses between visualized neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:7–9. doi: 10.1038/71082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bittman K, Becker DL, Cicirata F, Parnavelas JG. Connexin expression in homotypic and heterotypic cell coupling in the developing cerebral cortex. J Comp Neurol. 2002;443:201–212. doi: 10.1002/cne.2121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanc EM, Bruce-Keller AJ, Mattson MP. Astrocytic gap junctional communication decreases neuronal vulnerability to oxidative stress-induced disruption of Ca2+ homeostasis and cell death. J Neurochem. 1998;70:958–970. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70030958.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohmer C, Kirschner U, Wehner F. 18-beta-Glycyrrhetinic acid (BGA) as an electrical uncoupler for intracellular recordings in confluent monolayer cultures. Pflugers Arch. 2001;442:688–692. doi: 10.1007/s004240100588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruzzone R, White TW, Paul DL. Connections with connexins: the molecular basis of direct intercellular signaling. Eur J Biochem. 1996;238:1–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0001q.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhl DL, Harris KD, Hormuzdi SG, Monyer H, Buzsaki G. Selective impairment of hippocampal gamma oscillations in connexin-36 knock-out mouse in vivo. J Neurosci. 2003;23:1013–1018. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-03-01013.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzsaki G. Electrical wiring of the oscillating brain. Neuron. 2001;31:342–344. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00378-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connors BW, Benardo LS, Prince DA. Coupling between neurons of the developing rat neocortex. J Neurosci. 1983;3:773–782. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.03-04-00773.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Curtis M, Manfridi A, Biella G. Activity-dependent pH shifts and periodic recurrence of spontaneous interictal spikes in a model of focal epileptogenesis. J Neurosci. 1998;18:7543–7551. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-18-07543.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devor A, Yarom Y. Electrotonic coupling in the inferior olivary nucleus revealed by simultaneous double patch recordings. J Neurophysiol. 2002;87:3048–3058. doi: 10.1152/jn.2002.87.6.3048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudek FE, Patrylo PR, Wuarin JP. Mechanisms of neuronal synchronization during epileptiform activity. Adv Neurol. 1999;79:699–708. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields RD, Stevens-Graham B. New insights into neuron-glia communication. Science. 2002;298:556–562. doi: 10.1126/science.298.5593.556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froes MM, Correia AH, Garcia-Abreu J, Spray DC, Campos de Carvalho AC, Neto MV. Gap-junctional coupling between neurons and astrocytes in primary central nervous system cultures. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:7541–7546. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita K, Nakanishi K, Sobue K, Ueki T, Asai K, Kato T. Astrocytic gap junction blockage and neuronal Ca2+ oscillation in neuron-astrocyte cocultures in vitro. Neurochem Int. 1998;33:41–49. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(05)80007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galarreta M, Hestrin S. Electrical and chemical synapses among parvalbumin fast-spiking GABAergic interneurons in adult mouse neocortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:12438–12443. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192159599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giaume C, Cordier J, Glowinski J. Endothelins inhibit junctional permeability in cultured mouse astrocytes. Eur J Neurosci. 1992;4:877–881. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1992.tb00198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giaume C, McCarthy KD. Control of gap-junctional communication in astrocytic networks. Trends Neurosci. 1996;19:319–325. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(96)10046-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladwell SJ, Jefferys JG. Second messenger modulation of electrotonic coupling between region CA3 pyramidal cell axons in the rat hippocampus. Neurosci Lett. 2001;300:1–4. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)01530-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hormuzdi SG, Pais I, LeBeau FE, Towers SK, Rozov A, Buhl EH, Whittington MA, Monyer H. Impaired electrical signaling disrupts gamma frequency oscillations in connexin 36-deficient mice. Neuron. 2001;31:487–495. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00387-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishimatsu M, Williams JT. Synchronous activity in locus coeruleus results from dendritic interactions in pericoerulear regions. J Neurosci. 1996;16:5196–5204. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-16-05196.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang J, Jiang L, Goldman SA, Nedergaard M. Astrocyte-mediated potentiation of inhibitory synaptic transmission. Nat Neurosci. 1998;1:683–692. doi: 10.1038/3684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kistler WM, De Jeu MT, Elgersma Y, Van Der Giessen RS, Hensbroek R, Luo C, Koekkoek SK, Hoogenraad CC, Hamers FP, Gueldenagel M, Sohl G, Willecke K, De Zeeuw CI. Analysis of Cx36 knockout does not support tenet that olivary gap junctions are required for complex spike synchronization and normal motor performance. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;978:391–404. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb07582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohling R, Gladwell SJ, Bracci E, Vreugdenhil M, Jefferys JG. Prolonged epileptiform bursting induced by 0-Mg(2+). in rat hippocampal slices depends on gap junctional coupling. Neuroscience. 2001;105:579–587. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00222-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung DS, Unsicker K, Reuss B. Gap junctions modulate survival-promoting effects of fibroblast growth factor-2 on cultured midbrain dopaminergic neurons. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2001;18:44–55. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2001.1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo Turco JJ, Kriegstein AR. Clusters of coupled neuroblasts in embryonic neocortex. Science. 1991;252:563–566. doi: 10.1126/science.1850552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long MA, Deans MR, Paul DL, Connors BW. Rhythmicity without synchrony in the electrically uncoupled inferior olive. J Neurosci. 2002;22:10898–10905. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-24-10898.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick DA, Contreras D. On the cellular and network bases of epileptic seizures. Annu Rev Physiol. 2001;63:815–846. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.63.1.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier N, Guldenagel M, Sohl G, Siegmund H, Willecke K, Draguhn A. Reduction of high-frequency network oscillations (ripples). and pathological network discharges in hippocampal slices from connexin 36- deficient mice. J Physiol. 2002;541:521–528. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.017624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margineanu DG, Klitgaard H. Can gap-junction blockade preferentially inhibit neuronal hypersynchrony vs. excitability. Neuropharmacology. 2001;41:377–383. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(01)00080-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier C, Petrasch-Parwez E, Habbes HW, Teubner B, Guldenagel M, Degen J, Sohl G, Willecke K, Dermietzel R. Immunohistochemical detection of the neuronal connexin36 in the mouse central nervous system in comparison to connexin36-deficient tissues. Histochem Cell Biol. 2002;117:461–471. doi: 10.1007/s00418-002-0417-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercier F, Hatton GI. Connexin26 and basic fibroblast growth factor are expressed primarily in the subpial and subependymal layers in adult brain parenchyma: roles in stem cell proliferation and morphological plasticity. J Comp Neurol. 2001;431:88–104. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20010226)431:1<88::aid-cne1057>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oguro K, Jover T, Tanaka H, Lin Y, Kojima T, Oguro N, Groom SY, Bennett MV, Zukin RS. Global ischemia-induced increases in the gap junctional proteins connexin32 (Cx32) and Cx36 in hippocampus and enhanced vulnerability of Cx32 knock-out mice. J Neurosci. 2001;21:7534–7542. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-19-07534.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne PB, Williams JT. Forskolin enhancement of opioid currents in rat locus coeruleus neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1996;76:1559–1565. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.76.3.1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papa M, Bundman MC, Greenberger V, Segal M. Morphological analysis of dendritic spine development in primary cultures of hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 1995;15:1–11. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-01-00001.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parri HR, Gould TM, Crunelli V. Spontaneous astrocytic Ca2+ oscillations in situ drive NMDAR-mediated neuronal excitation. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:803–812. doi: 10.1038/90507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez Velazquez JL, Carlen PL. Gap junctions, synchrony and seizures. Trends Neurosci. 2000;23:68–74. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(99)01497-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez Velazquez JL, Frantseva M, Naus CC, Bechberger JF, Juneja SC, Velumian A, Carlen PL, Kidder GM, Mills LR. Development of astrocytes and neurons in cultured brain slices from mice lacking connexin43. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1996;97:293–296. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(96)00156-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pocock G, Richards CD. Excitatory and inhibitory synaptic mechanisms in anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 1993;71:134–147. doi: 10.1093/bja/71.1.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puil E, El-Beheiry H. Anaesthetic suppression of transmitter actions in neocortex. Br J Pharmacol. 1990;101:61–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1990.tb12089.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puil E, El-Beheiry H, Baimbridge KG. Anesthetic effects on glutamate-stimulated increase in intraneuronal calcium. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1990;255:955–961. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rash JE, Staines WA, Yasumura T, Patel D, Furman CS, Stelmack GL, Nagy JI. Immunogold evidence that neuronal gap junctions in adult rat brain and spinal cord contain connexin-36 but not connexin-32 or connexin-43. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:7573–7578. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.13.7573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rash JE, Yasumura T, Dudek FE, Nagy JI. Cell-specific expression of connexins and evidence of restricted gap junctional coupling between glial cells and between neurons. J Neurosci. 2001;21:1983–2000. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-06-01983.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reaume AG, De Sousa PA, Kulkarni S, Langille BL, Zhu D, Davies TC, Juneja SC, Kidder GM, Rossant J. Cardiac malformation in neonatal mice lacking connexin43. Science. 1995;267:1831–1834. doi: 10.1126/science.7892609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rekling JC, Shao XM, Feldman JL. Electrical coupling and excitatory synaptic transmission between rhythmogenic respiratory neurons in the preBotzinger complex. J Neurosci. 2000;20:RC113. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-23-j0003.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rorig B, Klausa G, Sutor B. Intracellular acidification reduced gap junction coupling between immature rat neocortical pyramidal neurones. J Physiol. 1996;490:31–49. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross FM, Gwyn P, Spanswick D, Davies SN. Carbenoxolone depresses spontaneous epileptiform activity in the CA1 region of rat hippocampal slices. Neuroscience. 2000;100:789–796. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00346-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouach N, Avignone E, Meme W, Koulakoff A, Venance L, Blomstrand F, Giaume C. Gap junctions and connexin expression in the normal and pathological central nervous system. Biol Cell. 2002;94:457–475. doi: 10.1016/s0248-4900(02)00016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouach N, Giaume C. Connexins and gap junctional communication in astrocytes are targets for neuroglial interaction. Prog Brain Res. 2001;132:203–214. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(01)32077-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouach N, Glowinski J, Giaume C. Activity-dependent neuronal control of gap-junctional communication in astrocytes. J Cell Biol. 2000;149:1513–1526. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.7.1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozental R, Andrade-Rozental AF, Zheng X, Urban M, Spray DC, Chiu FC. Gap junction-mediated bidirectional signaling between human fetal hippocampal neurons and astrocytes. Dev Neurosci. 2001a;23:420–431. doi: 10.1159/000048729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozental R, Srinivas M, Spray DC. How to close a gap junction channel. Efficacies and potencies of uncoupling agents. Methods Mol Biol. 2001b;154:447–476. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-043-8:447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacchi O, Rossi ML, Canella R, Fesce R. Participation of a chloride conductance in the subthreshold behavior of the rat sympathetic neuron. J Neurophysiol. 1999;82:1662–1675. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.4.1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz D, Schuchmann S, Fisahn A, Draguhn A, Buhl EH, Petrasch-Parwez E, Dermietzel R, Heinemann U, Traub RD. Axo-axonal coupling. a novel mechanism for ultrafast neuronal communication. Neuron. 2001;31:831–840. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00410-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sotelo C, Korn H. Morphological correlates of electrical and other interactions through low-resistance pathways between neurons of the vertebrate central nervous system. Int Rev Cytol. 1978;55:67–107. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)61887-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spray DC, Duffy HS, Scemes E. Gap junctions in glia. Types, roles, and plasticity. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1999;468:339–359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traub RD, Bibbig R, Piechotta A, Draguhn R, Schmitz D. Synaptic and nonsynaptic contributions to giant ipsps and ectopic spikes induced by 4-aminopyridine in the hippocampus in vitro. J Neurophysiol. 2001;85:1246–1256. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.3.1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traub RD, Draguhn A, Whittington MA, Baldeweg T, Bibbig A, Buhl EH, Schmitz D. Axonal gap junctions between principal neurons: a novel source of network oscillations, and perhaps epileptogenesis. Rev Neurosci. 2002;13:1–30. doi: 10.1515/revneuro.2002.13.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travagli RA, Dunwiddie TV, Williams JT. Opioid inhibition in locus coeruleus. J Neurophysiol. 1995;74:518–528. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.74.2.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaillend C, Mason SE, Cuttle MF, Alger BE. Mechanisms of neuronal hyperexcitability caused by partial inhibition of Na(+)-K(+)-ATPases in the rat CA1 hippocampal region. J Neurophysiol. 2002;88:2963–2978. doi: 10.1152/jn.00244.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venance L, Rozov A, Blatow M, Burnashev N, Feldmeyer D, Monyer H. Connexin expression in electrically coupled postnatal rat brain neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:10260–10265. doi: 10.1073/pnas.160037097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]