Abstract

A key strategy in microbial pathogenesis is the subversion of the first line of cellular immune defences presented by professional phagocytes. Enteropathogenic and enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EPEC and EHEC respectively) remain extracellular while colonizing the gut mucosa by attaching and effacing mechanism. EPEC use the type three secretion system effector protein EspF to prevent their own uptake into macrophages. EPEC can also block in trans the internalization of IgG-opsonized particles. In this study, we show that EspJ is the type three secretion system effector protein responsible for trans-inhibition of macrophage opsono-phagocytosis by both EPEC and EHEC. While EspF plays no role in trans-inhibition of opsono-phagocytosis, espJ mutants of EPEC or EHEC are unable to block uptake of opsonized sheep red blood cells (RBC), a phenotype that is rescued upon complementation with the espJ gene. Importantly, ectopic expression of EspJEHEC in phagocytes is sufficient to inhibit internalization of both IgG- and C3bi-opsonized RBC. These results suggest that EspJ targets a basic mechanism common to these two unrelated phagocytic receptors. Moreover, EspF and EspJ target independent aspects of the phagocytic function of mammalian macrophages in vitro.

Introduction

Enteropathogenic and enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EPEC and EHEC respectively) belong to a family of medically important diarrhoeagenic pathogens, which colonize the gut mucosa by the attaching and effacing (A/E) mechanism (for review, see Kaper et al., 2004). The genes responsible for the A/E phenotype are carried on the locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE) pathogenicity island (McDaniel et al., 1995), which encodes transcriptional regulators, the adhesin intimin (Jerse et al., 1990), structural components of a type three secretion system (T3SS) (Jarvis et al., 1995), chaperones, as well as translocator and effector proteins (reviewed in Garmendia et al., 2005). A/E lesions are characterized by localized destruction of the brush border microvilli and intimate attachment of the bacteria to the apical membrane of enterocytes (Knutton et al., 1987).

EPEC and EHEC use the T3SS to inject into mammalian host cells dozens of effector proteins (Garmendia et al., 2005; Spears et al., 2006; Tobe et al., 2006), which target different subcellular compartments and affect diverse signalling pathways and physiological processes. Among the effector proteins are EspI/NleA which is targeted to the Golgi apparatus (Gruenheid et al., 2004; Mundy et al., 2004), EspG and EspG2 which disrupt the microtubule network (Matsuzawa et al., 2004; Hardwidge et al., 2005; Shaw et al., 2005a; Tomson et al., 2005); EspF which is targeted to the mitochondria and involved in disruption of the tight junction barrier, elongation of the intestinal brush border microvilli and cell death (Crane et al., 2001; McNamara et al., 2001; Nougayrède and Donnenberg, 2004; Nagai et al., 2005; Shaw et al., 2005b); Map which induces filopodia formation (Kenny et al., 2002); and Tir which downregulates Map-induced signals (Kenny et al., 2002) and is involved in extensive remodelling of the intermediate filament and the actin microfilament networks (Kenny et al., 1997; reviewed in Caron et al., 2006).

Avoidance of phagocytosis and the undermining of macrophage signalling are common strategies used by pathogenic bacteria to colonize the host while evading immune defences (Coombes et al., 2004). Phagocytosis is the process by which macrophage, neutrophils and dendritic cells internalize particulate material over 0.5 μm in diameter. Phagocytic uptake is a multistep, zipper-like process, initiated by the ligation of surface receptors and driven by a local remodelling of the actin cytoskeleton. The two best-characterized phagocytic receptors, complement receptor 3 (CR3) and Fc gamma receptors (FcγR), bind to opsonins deposited onto their targets, respectively, complement fragment C3bi and IgG. These two receptors are thought to mediate most of the phagocytic events occurring during innate and adaptive immune responses. Despite a conservation in principles, the mechanisms of internalization through CR3 and FcγR are known to involve different mechanisms and signalling pathways (Allen and Aderem, 1996; Caron and Hall, 1998).

EPEC and EHEC colonize the gut epithelium while remaining extracellular. Interestingly, EPEC is able to block its own uptake by professional phagocytes, a process we refer to as cis-inhibition of phagocytosis (Goosney et al., 1999; Celli et al., 2001; Quitard et al., 2006). The mechanism involved depends on the T3SS effector EspF but is poorly understood, although subversion of a phosphatidyl inositol 3-kinase (PI3K)-controlled pathway has been invoked (Celli et al., 2001; Quitard et al., 2006). Importantly, EPEC were also reported to inhibit in trans the phagocytosis of IgG-opsonized zymosan particles via the FcγR upon infection of macrophages (Celli et al., 2001), although the mechanism involved is not known. The aim of this study was to investigate the basis for EPEC O127:H6 trans-antiphagocytic activity and to determine if the same mechanism is shared with EHEC O157:H7, which is the most common virulent EHEC serotype.

Results

EPEC inhibit opsono-phagocytosis in a T3SS-dependent mechanism

J774.A1 macrophages were infected for 1 h with wild-type EPEC O127:H6 (strain E2348/69) and in parallel with its isogenic T3SS-deficient EPECΔescN mutant (strain ICC192) (Garmendia et al., 2004). Uninfected macrophages were used as control. To maximize LEE gene expression EPEC strains were primed for 3 h in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) prior to infection (Collington et al., 1998). In order to assist detection of bacteria in infected macrophages, strains were transformed with a GFP-expressing plasmid (pFVp25.1). After infection, macrophages were washed then challenged with sheep red blood cells (RBC) pre-opsonized with either rabbit IgG or IgM and C5-deficient serum, to direct RBC for phagocytosis through FcγR and CR3 respectively (Caron and Hall, 1998). Macrophages were then fixed and RBC differentially labelled pre- and post-permeabilization in order to discriminate extracellular from phagocytosed RBC. Infection of J774.A1 macrophages with wild-type EPEC dramatically reduced uptake of both IgG- and C3bi-opsonized RBC (Fig. 1). In contrast, infection with the escN mutant resulted in phagocytosis of RBC at a comparable level to the non-infected control (Figs 1A and 3B).

Fig. 1.

EPEC inhibit FcγR-mediated phagocytosis in a T3SS-dependent manner. J774.A1 macrophages (A) or FcγR-transfected Cos cells (B) were left uninfected (control) or infected with primed wild-type (wt) and ΔescN (escN) EPEC strains for 1 h and then challenged with IgG-RBC for 30 min. Cells were processed for immunofluorescence and scored for phagocytic index, i.e. the number of RBC bound to 100 cells. Values are expressed relative to the non-infected control (none) values which were set up at 100. Results are the mean ± SD of two independent experiments. Asterisks (*) denote a statistically significant difference with the wild-type strain.

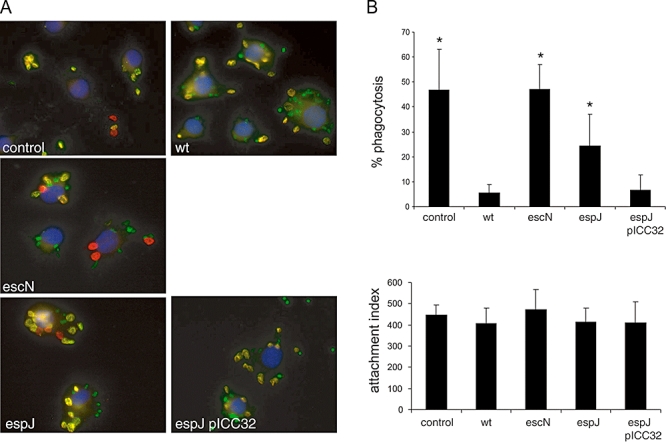

Fig. 3.

EPEC inhibition of CR3-mediated phagocytosis is EspJ dependent. J774.A1 macrophages were left uninfected (control) or infected for 1 h with primed wild-type (wt), ΔescN (escN), ΔespJ (espJ) and complemented ΔespJ pICC32 (espJ pICC32) EPEC strains, treated with 150 ng ml−1 PMA to activate the C3bi binding site on CR3 receptors, then challenged with C3bi-opsonized RBC for 30 min. Extracellular RBC were stained in green using Alexa™488-conjugated anti-rabbit antibodies and, after permeabilization, all cell-associated RBC were stained in red using rhodamine-conjugated anti-rabbit antibodies; cell nuclei were stained with DAPI. All bacteria are transformed with a GFP-expressing plasmid. A. Representative merged images of control cells and of macrophages infected with wild-type, ΔescN, ΔespJ, and complemented ΔespJ pICC32 with bacteria in green (GFP), cell nuclei in blue, internalized RBC in red and extracellular RBC in yellow (merge of green and red channels). B. Quantification of phagocytosis (defined as percentage bound RBC that are internalized) and attachment index (defined as the number of RBC bound to 100 macrophages). Results are the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. Asterisks (*) denote a statistically significant difference with the wild-type strain.

Cos-7 cells transfected with phagocytic receptors provide an alternative model to study opsono-phagocytosis in isolation from macrophage receptors and secreted products (Caron and Hall, 1998). In order to confirm the results observed in J774.A1, Cos-7 cells were transfected with a construct encoding human FcγRIIA, which confers strong IgG-dependent phagocytic ability; then infected with EPEC strains and challenged with IgG-opsonized RBC. Infection with wild-type EPEC abrogated phagocytosis of opsonized RBC, as seen in J774.A1 macrophages. In contrast, when infected with EPECΔescN, efficient phagocytosis of RBC via the FcγR was observed (Fig. 1B).

EspJ mediates EPEC trans-antiphagocytic activity

In order to identify the EPEC T3SS effector responsible for the trans-inhibition of opsono-phagocytosis, we tested a collection of T3SS effector mutants (listed in Table 1) for their ability to inhibit FcγR-dependent phagocytosis. The striking difference in RBC phagocytosis distinguishing T3SS-competent (< 4% of the bound RBC are internalized) and T3SS-deficient (> 40% of the bound RBC are internalized) strains allowed us to make a rapid visual screen for mutants impaired in their ability to block FcγR-mediated uptake (Fig. 2A and B). Phagocytosis protects internalized RBC from antibody labelling in non-permeabilized cells, which makes them appear red under the microscope (Fig. 2A). None of the 17 effector mutant strains had any effect on the ability of IgG-opsonized RBC to bind macrophages (Fig. 2B, bottom and data not shown). The only mutant showing a significantly greater number of phagocytosed RBC than the parental strain was EPECΔespJ (strain ICC190) (Dahan et al., 2005). Quantitative analysis revealed that infection of J774.A1 macrophages with EPECΔespJ resulted in a level of RBC phagocytosis equivalent to that seen in cells infected with EPECΔescN or in uninfected controls (Fig. 2B). To verify the dependency of this inhibitory activity upon EspJ, we complemented the espJ mutant strain ICC190 with a plasmid encoding full-length EspJ (pICC32). Expression of recombinant EspJ restored the ability of the ΔespJ mutant to inhibit FcγR-dependent phagocytosis to a similar level as wild-type EPEC (P > 0.05). These results demonstrate that EspJ is the main T3SS effector involved in the trans-inhibition of FcγR-mediated phagocytosis by EPEC. Interestingly, although EspF has recently been implicated in the inhibition of EPEC phagocytosis by macrophages (Quitard et al., 2006), we detected no statistically significant difference in the uptake of IgG-opsonized RBC by J774.A1 macrophages infected with either wild-type EPEC or the isogenic EPECΔespF mutant (Fig. 2B).

Table 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study.

| Strains/plasmids | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| 85-170 | EHEC O157:H7 spontaneous stx1−stx2−, NalR | Stevens et al. (2004) |

| ICC217 | ΔescN::Kn in 85-170, KnR | This study |

| ICC188 | ΔespJ::Kn in 85-170, KnR | Dahan et al. (2005) |

| EDL933 | EHEC O157:H7 stx− | ATCC |

| ICC187 | ΔescN::Kn in EHEC O157:H7 strain EDL933 | Garmendia et al. (2004) |

| ICC184 | ΔespF::Kn in EHEC O157:H7 strain EDL933 | Garmendia et al. (2004) |

| E2348/69 | EPEC O127:H6 | Levine et al. (1978) |

| ICC192 | ΔescN::Kn in E2348/69, KnR | Garmendia et al. (2004) |

| ICC211 | ΔespF::Kn in E2348/69, KnR | Marchès et al. (2006) |

| ICC190 | ΔespJ::Kn in E2348/69, KnR | Dahan et al. (2005) |

| ICC193 | ΔnleC::Kn in E2348/69, KnR | Marchès et al. (2005) |

| ICC194 | ΔnleD::Kn in E2348/69, KnR | Marchès et al. (2005) |

| ICC225 | Δtir::Kn in E2348/69, KnR | This study |

| ICC257 | Δeae::Kn in E2348/69, KnR | This study |

| ICC243 | ΔespG1::KnΔespG2::Cm in E2348/69, KnR CmR | This study |

| ICC202 | Δmap::Kn in E2348/69, KnR | Simpson et al. (2006) |

| ICC246 | ΔespH::Kn in E2348/69, KnR | This study |

| MK41 | ΔsepZ::AphT3 in E2348/69, KnR | Kanack et al. (2005) |

| ICC249 | Δmap::KnΔespF::Cm in E2348/69, KnR CmR | This study |

| ICC254 | ΔnleH1::KnΔnleH2::Cm in E2348/69, KnR CmR | This study |

| ICC248 | ΔespI::Kn in E2348/69, KnR | This study |

| ICC256 | ΔnleI::Kn in E2348/69, KnR | This study |

| ICC252 | ΔnleF::Kn in E2348/69, KnR | This study |

| ICC250 | ΔnleB1::Cm in E2348/69, CmR | This study |

| ICC251 | ΔnleB2::Kn in E2348/69, KnR | This study |

| Plasmid | ||

| pICC32 | Derivative of pSA10 (Schlosser-Silverman et al., 2000) encoding EspJEPEC–FLAG fusion protein | This study |

| pICC31 | Derivative of pSA10 encoding EspJEHEC–FLAG fusion protein | This study |

| pRK5-EspJEHEC–FLAG | Derivative of pRK5 (BD Pharmingen) encoding EspJEHEC–FLAG fusion protein | This study |

| pFPV25.1 | Plasmid expressing gfpmut3a gene | Valdivia and Falkow (1996) |

| pSB315 | Source of aphT cassette | Dahan et al. (2005) |

| pKD3 | oriRγ, blaM, CmR cassette flanked by FRT sites | Datsenko and Wanner (2000) |

| pKD4 | oriRγ, blaM, KanR cassette flanked by FRT sites | Datsenko and Wanner (2000) |

| pKD46 | ori101, repA 101 (ts), araBp-gam-bet-exo, blaM | Datsenko and Wanner (2000) |

Fig. 2.

EPEC inhibition of FcγR-mediated phagocytosis is EspF-independent but requires translocation of EspJ. J774.A1 macrophages were left uninfected (control) or infected for 1 h with primed wild-type (wt), ΔescN (escN), ΔespF (espF), ΔespJ (espJ) and complemented ΔespJ pICC32 (espJ pICC32) EPEC strains and then challenged with IgG-RBC for 30 min. Extracellular RBC were stained in green using Alexa™488-conjugated anti-rabbit antibodies and, after permeabilization, all cell-associated RBC were stained in red using rhodamine-conjugated anti-rabbit antibodies; cell nuclei were stained with DAPI. All bacteria are transformed with a GFP expressing plasmid. A. Representative merged images of control cells or of macrophages infected with wild-type, ΔescN, ΔespF, ΔespJ, and complemented ΔespJ pICC32 with bacteria in green (GFP), cell nuclei in blue, internalized RBC in red and extracellular RBC in yellow (merge of green and red channels). B. Quantification of phagocytosis (defined as percentage bound RBC that are internalized) and attachment index (defined as the number of RBC bound to 100 macrophages). Results are the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. Asterisks (*) denote a statistically significant difference with the wild-type strain.

EspJ impairs CR3-mediated uptake

To study whether the antiphagocytic function of EPEC EspJ is general or specific to the FcγR-dependent signalling pathway, we examined the impact of EspJ on CR3-mediated phagocytosis. Although phagocytosis mediated by FcγR or CR3 is opsonin-dependent and actin-driven, the signalling pathways responsible for actin polymerization downstream of these two receptors are different (Caron and Hall, 1998). J774.A1 macrophages were left uninfected or infected with wild-type EPEC, EPECΔescN, EPECΔespJ and EPECΔespJ (pICC32) (complemented), before challenge with C3bi-opsonized RBC. Wild-type EPEC inhibited phagocytosis of C3bi-opsonized RBC in a T3SS-dependent manner as no inhibition was seen after infection with EPECΔescN (Fig. 3B). Deletion of espJ also impaired the ability of EPEC to block CR3-dependent uptake, reducing it to a level similar to EPECΔescN (Fig. 3A and B). Complementing the EPECΔespJ mutant restored the inhibition of C3bi-opsonized RBC uptake by infected macrophages close to wild-type EPEC levels (Fig. 3A and B). As seen for IgG-opsonized RBC, pre-infection with EPEC strains had no impact on the attachment of C3bi-opsonized RBC, suggesting that translocated EspJ does not interfere with surface expression of the phagocytic receptors (FcγR and CR3 respectively) but instead with a regulatory mechanism essential for both CR3- and FcγR-dependent uptake. These results show that EspJ inhibits opsono-phagocytosis via both the CR3 and FcγR receptors.

EspJ from EHEC O157:H7 inhibits opsono-phagocytosis

Whether or not EHEC O157:H7 have antiphagocytic activity is unknown. As espJ is conserved between EPEC and EHEC (Dahan et al., 2005), we examined whether EspJ mediates antiphagocytosis during EHEC infection of J774.A1 macrophages. J774.A1 were infected with the spontaneous stx minus EHEC O157:H7 strain 85-170 and its isogenic mutants EHECΔescN and EHECΔespJ (Table 1) before challenge with IgG- or C3bi-opsonized RBC. As shown in Fig. 4A and B, both FcγR- and CR3-dependent uptake of RBC were greatly diminished in J774.A1 infected with the parental EHEC strain compared with the levels of uptake observed in uninfected macrophages (control) or in cells infected with the EHECΔescN or EHECΔespJ. Complementing the ΔespJ strain with a plasmid encoding either EspJEPEC or EspJEHEC restored the ability of the mutant strain to inhibit phagocytosis of IgG- and C3bi-opsonized RBC (Fig. 4A and B). As for EPEC (Fig. 3), impaired RBC phagocytosis was unrelated to changes in RBC adhesion, which indicates that antiphagocytosis is due to impaired phagocytic signalling.

Fig. 4.

EHEC inhibits opsono-phagocytosis through the translocated effector EspJ. J774.A1 macrophages were left uninfected (control) or infected with EHEC wild-type (wt), ΔescN (escN), ΔespJ (espJ), or complemented ΔespJ pICC31 (espJ pICC31) for 4 h and then challenged with IgG-opsonized RBC (A) or C3bi-opsonized RBC (B) for 30 min and processed for immunofluorescence as described in Experimental procedures. Quantification of phagocytosis (defined as percentage bound RBC that are internalized) and attachment index (defined as the number of RBC bound to 100 macrophages) for FcγR- (A) and CR3- (B) mediated phagocytosis are shown. Results are the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. Asterisks (*) denote a statistically significant difference with the wild-type strain.

EspF, not EspJ, is required for inhibition of bacterial phagocytosis

Several reports have involved EspF in bacterial-induced inhibition of EPEC phagocytosis by M cells and cultured macrophages (Quitard et al., 2006; Martinez-Argudo et al., 2007), a finding we have confirmed in this study (data not shown). However, no data exist on the potential inhibition of bacterial uptake by EHEC. To address this question, J774.A1 macrophages were infected for 4 h with wild-type, ΔescN, ΔespJ and ΔespF EHEC strains and the attachment indices and percentage phagocytosis were scored. As shown in Fig. 5, EHEC bacteria are able to interfere with their own uptake in a T3SS-dependent manner, as ΔescN bacteria were more readily phagocytosed than the wild-type control. Importantly, ΔespF EHEC behaved as the T3SS-deficient ΔescN isogenic control, showing that EspFEHEC, like EspFEPEC, controls cis-inhibition of phagocytosis. In contrast, ΔespJ EHEC were unimpaired in their ability to inhibit bacterial phagocytosis, establishing that two distinct molecular mechanisms control cis- and trans-inhibition of phagocytosis by EPEC and EHEC.

Fig. 5.

EspF, but not EspJ, controls cis-inhibition of EHEC phagocytosis in macrophages. J774.A1 macrophages were infected for 4 h at 37°C with 1:100 dilutions of overnight cultures of GFP-expressing EHEC O157:H7 strains as indicated and processed for immunofluorescence. Extracellular bacteria were stained red, as described in Experimental procedures, and were therefore easily distinguishable from internalized bacteria, which are solely green. The percentage of bound EHEC internalized (% phagocytosis) and the total number of cell-associated bacteria (attachment index) were scored under the epifluorescence microscope. Results are expressed as mean ± SD from three independent experiments, with ≥ 100 macrophages scored per condition per experiment. Asterisks (*) denote a statistically significant difference with the wild-type strain.

EspJ expression is sufficient for antiphagocytosis in transfected Cos-7 cells

Given the striking phenotype exhibited by espJ mutant strains on the inhibition of FcγR- and CR3-dependent phagocytic pathways, we examined if ectopic expression of EspJ in phagocytes was sufficient to impair opsono-phagocytosis. espJEHEC was cloned into the pRK5-FLAG eukaryotic expression vector and co-transfected with the FcγRIIA or CR3 phagocytic receptors. Cells were then challenged with IgG- or C3bi-opsonized RBC and scored for RBC binding and phagocytosis. EspJ expression had no effect on the binding of C3bi- or IgG-opsonized RBC to receptor transfected Cos-7 cells (data not shown). In contrast, a clear and statistically significant inhibition of both FcγR- and CR3-mediated uptake was observed in EspJ-expressing Cos-7 cells (Fig. 6A and B), showing that the expression of EspJ inside host cells is sufficient for inhibition of opsono-phagocytosis.

Fig. 6.

Intracellular expression of EspJ is sufficient for inhibition of FcγR- and CR3-mediated phagocytosis. Cos-7 cells were co-transfected by nucleofection with FcγRIIA (A) or CR3 receptor (B) and either with plasmid pRK5 or with pRK5-EspJ overexpressing EspJ from EHEC and were then challenged for 30 min with IgG- (A) or C3bi- (B) opsonized RBC. RBC phagocytosis was then quantified as described in Experimental procedures, the transfected cells being easily distinguishable from non-transfected cells by their unique ability to bind opsonized RBC. Results are the mean ± SD of at least two independent experiments.

The presence of a FLAG tag on EspJ allowed us to examine the basic features of the inhibition in trans of opsono-phagocytosis. Overexpressed EspJ was excluded from the nucleus and localized throughout the cytosol of Cos-7 cells, both in a diffuse fashion and in large aggregates. RBC challenge of Cos-7 cells coexpressing FcγRIIA and EspJ did not affect the overall localization of EspJ (Fig. 7 and data not shown). Interestingly, ectopically expressed EspJ did not specifically accumulate to any significant extent at the plasma membrane or at sites of RBC attachment. Moreover, EspJ expression did not prevent actin polymerization underneath bound IgG-opsonized RBC (Fig. 7, top, arrowhead). Overall, these data suggest that EspJ blocks FcγR-mediated phagocytosis from a distance, rather than acting locally at the nascent phagocytic cup, possibly by interfering with the later stages of RBC uptake, after initial F-actin polymerization has taken place.

Fig. 7.

Intracellular distribution of ectopically expressed EspJ during FcγR-dependent uptake. Cos-7 cells were co-transfected with FcγRIIa and either with pRK5-EspJFLAG (top) or with empty pRK5 (bottom) and challenged with IgG-opsonized RBC for 30 min at 37°C, as described in the legend to Fig. 5. RBC-challenged cells were permeabilized and stained with an anti-flag mouse monoclonal followed by Cy2-conjugated anti-mouse antibodies (green), rhodamine phalloidin to visualize F-actin (red) and Cy5-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG-RBC (blue). Cells were observed by confocal microscopy; representative examples are shown. Scale bar, 10 μm.

Discussion

In the past few years antiphagocytosis has been proposed as a pathogenic mechanism for EPEC (Celli et al., 2001). However the molecular basis of this phenomenon is poorly understood. Antiphagocytic activity is clearly dependent on the translocation of one or more effectors through the EPEC T3SS into the cytosol of macrophage-like cells and manifests itself both as an ability of EPEC to reduce their own uptake (cis-inhibition) and to block in trans the phagocytosis of IgG-opsonized zymosan particles through FcγR (trans-inhibition) (Goosney et al., 1999; Celli et al., 2001). Whether these two phenotypes correspond to a unique mechanism or reflects the existence of two independent antiphagocytic mechanisms was unknown. Other bacterial pathogens are known to modulate phagocytosis, either – like Salmonella typhimurium and Shigella flexneri– by stimulating their uptake by non-professional phagocytes or – like Yersinia and Clostridium spp. – by blocking phagocytic signalling in phagocytic cells. In all cases the underlying mechanisms involve the subversion of actin dynamics (reviewed in Rottner et al., 2005).

The mechanism by which EPEC block their own uptake has been attributed to the effector EspF (Quitard et al., 2006). We report in this article that EHEC O157:H7 also block their own uptake by macrophages in an EspF-dependent manner (Fig. 5), suggesting that antiphagocytosis is a general mechanism displayed by both EHEC and EPEC. In this report we demonstrate that (i) EHEC, like EPEC, are able to block the uptake of opsonized particles, (ii) EPEC and EHEC trans-inhibition of phagocytosis is T3SS-dependent, and (iii) EspJ (EPEC and EHEC) is the effector protein responsible for the inhibition of both FcγR- and CR3-mediated phagocytosis, suggesting that EspJ targets an essential host molecule or complex normally involved downstream of these two phagocytic receptors. Two clostridium toxins, the B toxins from Clostridium difficile strains 10463 and 1470, inhibit FcγR- and CR3-mediated phagocytosis (Caron and Hall, 1998; Caron et al., 2000). Both glucosylate and inactivate members of the Rho family of small GTP-binding proteins, known to regulate actin polymerization during a variety of eukaryotic processes, including phagocytosis (Just et al., 1995; Chaves-Olarte et al., 1999; Jaffe and Hall, 2005; Niedergang and Chavrier, 2005). However, to our knowledge, EspJ is the first example of a type three secretion effector that blocks both FcγR- and CR3-mediated phagocytosis.

Our results show that, as has been shown for EPEC, EHEC can inhibit opsono-phagocytosis. This may not be surprising, as EHEC are thought to have evolved from EPEC through the acquisition of phages encoding a Shiga-like toxin (Reid et al., 2000). It will be interesting to check whether other strains able to induce A/E lesions can also block phagocytosis. In order to find the effector protein conferring EPEC the ability to block phagocytosis in trans, we screened 17 candidate effectors mutants we had accumulated in the lab. Interestingly, neither EspF, involved in inhibition of EPEC phagocytosis by macrophages and M cells (Quitard et al., 2006; Martinez-Argudo et al., 2007); Tir, involved in redistribution of intermediate filament proteins and triggering of actin polymerization; Map, involved in filopodia formation; or EspG/EspG2, involved in disruption of the microtubule network (reviewed in Garmendia et al., 2005 and Caron et al., 2006) were involved. In contrast, deletion of espJ, which is carried upstream of tccP (Garmendia et al., 2004) on prophage CP-933U/Sp14 in EHEC, abolished phagocytosis of opsonized RBC. The phagocytosis defect was complemented by recombinant espJ. Interestingly EspJ is dispensable for cis-inhibition of EHEC or EPEC uptake (Fig. 5 and V. Covarelli, O. Marchès, G. Frankel and E. Caron, unpubl. results). Taken together our results show that inhibition of cis- and trans-phagocytosis are mediated by different effectors and are likely to involve different signalling pathways.

Sequence analysis reveals, as expected, that EspJEPEC shows a very strong (79%) sequence identity at the amino acid level with EspJEHEC and an open reading frame (75% identity) in Citrobacter rodentium, the mouse A/E pathogen (Dahan et al., 2005). Interestingly, database searches also show a 57% identity (74% similarity) with a putative protein from Salmonella bongori. S. bongori mainly infects cold-blooded animals but is also associated to rare cases of acute enteritis in humans (Giammanco et al., 2002). As S. bongori differs from Salmonella enterica by the absence of the SPI-2 (Salmonella pathogenicity island two), whose expression is induced intracellularly and which is essential for intracellular survival and replication within macrophages (Ochman and Groisman, 1996; Waterman and Holden, 2003), it is tempting to speculate that an antiphagocytic protein would allow S. bongori to survive its interaction with phagocytic cells in its hosts.

Our study establishes that EspJ is necessary and sufficient to block uptake of C3bi- and IgG-opsonized RBC. In a previous study EPEC were shown to be unable to block uptake of C3bi-opsonized zymosan (Celli et al., 2001). The reason for this discrepancy is unclear. While zymosan and RBC are distinct phagocytic targets, opsonization with IgG or C3bi fragments should ensure that when opsonized the two types of particles interact with identical surface receptors FcγR and CR3 respectively. The only other difference between the two studies is the source of phagocytic cells [bone marrow macrophage-derived cell line in Celli et al. (2001); J774.A1 and transfected Cos-7 cells in this study]. Because we obtained similar results in a murine macrophage cell line and in Cos-7 cells transfected with either FcγRIIA or CR3, and because EspJ expression is sufficient to block phagocytosis, we strongly believe that EspJ targets a critical regulatory pathway activated downstream of the two receptors; this pathway is furthermore conserved both in macrophages and in Cos-7 cells.

What is the mechanism by which EspJ blocks FcγR- and CR3-mediated opsono-phagocytosis of RBC? On the one hand, bioinformatic searches on EspJ did not yield any recognizable domain or sequence that could help us clarify its function. On the other hand, phagocytosis through these two receptors is ultrastructurally, pharmacologically and functionally different. In macrophages, FcγR-mediated uptake is constitutive and pro-inflammatory, involves the protrusion of actin-rich pseudopods and is controlled by tyrosine kinases, Cdc42 and Rac activity; in contrast, CR3-dependent internalization is not accompanied by major protrusions or production of pro-inflammatory signals, does not require tyrosine kinase, Rac or Cdc42 activity but is dependent on RhoA activity for actin polymerization at sites of particle binding (Allen and Aderem, 1996; Caron and Hall, 1998; Niedergang and Chavrier, 2005). Nonetheless, these two modes of engulfment share two requirements: local actin polymerization and membrane delivery at sites of particle binding (Allen and Aderem, 1996; Braun and Niedergang, 2006). We show that F-actin is still detected at sites of RBC binding in EspJ-expressing cells, suggesting that EspJ could interfere with the delivery of membrane at nascent phagosomes. In line with this observation, EspJ is found on intracellular structures, possibly endomembranes, when ectopically expressed in Cos-7 cells and is not recruited to forming phagosomes. Phagocytosis is known to involve the focal delivery of membrane from various intracellular sources at sites of particle binding (Gagnon et al., 2002; Braun et al., 2004). Identification of the putative EspJ-rich compartment would help us shed light on the EspJ-dependent antiphagocytic mechanism, which might involve the blocking either of membrane per se or of some unknown membrane-borne regulator(s) of uptake.

Current understanding of infections by A/E pathogens points towards an extracellular lifestyle, with bacteria adhering strongly to the surface of enterocytes. In EPEC and EHEC, type three secretion, which controls formation of A/E lesions, is important for host colonization (reviewed in Spears et al., 2006). It is now clear that the T3SS also controls antiphagocytosis (Goosney et al., 1999; Celli et al., 2001; this report). Importantly, ultrastructural studies showed that EHEC O157:H7 colonize Peyer's patch mucosa ex vivo (Phillips et al., 2000), C. rodentium first targets the caecal patch in vivo (Wiles et al., 2004) while RDEC-1 (rabbit EPEC) first targets ileal M cells, an intestinal phagocyte that binds but does not internalize these bacteria, before spreading to other intestinal sites (Inman and Cantey, 1983). It is conceivable that EspF-mediated, cis-inhibition of phagocytosis (Quitard et al., 2006; Martinez-Argudo et al., 2007) allows A/E bacteria to prevent their internalization early on during infection and thereby facilitates colonization of the intestine. EspJ-mediated trans-inhibition could be a mechanism to ensure that bacteria-associated host cells are not internalized by phagocytic cells that are recruited to the lumen of the gut as a result of inflammation once colonization of the epithelial is established (Inman and Cantey, 1983) or after an adaptive immune response has been mounted. Further studies are needed to unravel the molecular basis of EspJ and EspF antiphagocytic activities and their respective roles in colonization and infection.

Experimental procedures

Bacterial strains

The wild-type strains EPEC O127:H6 E2349/68 and EHEC O157:H7 85-170 used in this study and their mutants are listed in Table 1. Bacteria were grown in Luria–Bertani (LB) medium or in DMEM supplemented with kanamycin (50 μg ml−1), chloramphenicol (5 μg ml−1) and carbenicillin (100 μg ml−1), when necessary. The mutant strains engineered during this study were constructed using the PCR one-step λ Red recombinase method (Datsenko and Wanner, 2000). Briefly, each mutation was obtained using a PCR product containing an antibiotic resistance gene flanked by the 50 bases from the 5′ and 3′ ends of the target gene. Plasmids pKD4, pKK3 and pSB315 were used as PCR template. The PCR products were electroporated into the recipient strains carrying the Red system expression plasmid pKD46 and mutants were selected on LB plates with kanamycin or chloramphenicol. Recombinant clones were cured of pKD46 plasmid by growth at the non-permissive temperature (42°C) and mutation confirmed by different PCR reactions using primers flanking the targeted region and primers into the antibiotic resistance gene.

Cell culture and transfection

Cells from the murine macrophage J774.A1 and simian kidney fibroblast Cos-7 cell lines (ATCC) were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS) and penicillin/streptomycin. J774.A1 were seeded on glass coverslips (13 mm diameter) in 24-well plates at a density of 5 × 104 cells per well 24 h before infection. Cos-7 cells were seeded on coverslips in 6 cm dishes (105 cells per dish) and transfected either by nucleofection (Amaxa, Cologne, Germany) or using the calcium/phosphate protocol (Cougoule et al., 2006). Briefly, DNA/calcium phosphate precipitates (10 μg of DNA/400 μl of calcium phosphate/6 cm dishes containing 3.6 ml of fresh medium) were added onto the cells for 16–18 h, washed and incubated in fresh medium for an additional 6 h.

Plasmids

pICC32 and pICC31 are derivatives of pSA10 (Schlosser-Silverman et al., 2000), a vector containing multiple cloning sites downstream of the tac promoter. Pair of primers EspJf1 5′-CGGAATTCATGCCAATCATAAAGAACTGC-3′ and EspJr1 5′-AAAACTGCAGTTATTTATCATCATCATCTTTATAATCTTTTTTGAGTGGGTGGATAT-3′ and pair of primers EspJf2 5′-CGGAATTCATGTCAATTATAAAAAACTGCTTATC-3′ and EspJr2 5′-AAAACTGCAGTTATTTATCATCATCATCTTTATAATCTTTTTTGAGAGGATATATGTCAAC-3′ were used to amplify espJ fused to a FLAG tag from the wild-type EPEC and the wild-type EHEC respectively. PCR products containing terminal EcoRI and PstI restriction sites were digested and cloned into pSA10, generating plasmids pICC32 and pICC31. Plasmid pRK5-EspJEHECFLAG encoding EspJ from EHEC fused to a FLAG tag was obtained by EcoRI and PstI digestion of the PCR fragment obtained with primers EspJf2–EspJr2 and cloning into the eukaryotic expression vector pRK5 (BD Pharmingen).

Phagocytic assay and immunofluorescence

Overnight EPEC cultures in LB were diluted 1:100 into DMEM containing 25 mM Hepes and 2 mM Glutamax (Invitrogen) and pre-activated by incubation for 3 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere before infection. EHEC bacteria were grown overnight in DMEM supplemented with 5% FCS and directly added onto mammalian cells. J774.A1 or Cos-7 cells were incubated for at least 1 h in serum-free medium then infected either for 1 h with EPEC at a multiplicity of infection (moi) of 20:1 or for 4 h with EHEC at a moi of 200:1, conditions that lead a similar average number of bacteria (20–50) interacting with each macrophage at the end of the infection period. Conditions for optimal induction of LEE expression and optimal association with host cells have been described previously (Garmendia et al., 2004; Quitard et al., 2006).

RBC phagocytosis

Monolayers of infected cells were then washed with PBS and challenged for 30 min at 37°C in 5% CO2 with 500 μl of IgG- or C3bi-opsonized sheep RBC (TCS) at a ratio of 30 RBC per cell. RBC were opsonized as previously described (Caron and Hall, 1998; Patel et al., 2002). Briefly, for FcγR-mediated phagocytosis, 0.5 μl of RBC per coverslip were opsonized for 30 min with a subagglutinating concentration of rabbit anti-RBC IgG (Cappel) in 1 ml of gelatin veronal buffer (GVB2+, Sigma), washed once with GVB2+ and re-suspended in 500 μl of DMEM/coverslip. For CR3-mediated phagocytosis, 0.5 μl of RBC per coverslip were opsonized with rabbit anti-RBC IgM (Cedarlane Laboratories) for 30 min at room temperature in 1 ml of GVB2+, pelleted, incubated for 20 min at 37°C with C5-deficient human serum (Sigma) and re-suspended in 500 μl of DMEM/coverslip. For efficient binding and phagocytosis of C3bi-opsonized RBC, J774.A1 were pre-treated with 150 ng ml−1 PMA in serum-free DMEM for 15 min before RBC challenge. After phagocytic challenge, cells were washed twice in PBS and fixed for 20 min in 4% paraformaldehyde. Free aldehyde groups were neutralized with 50 mM NH4Cl in PBS for 15 min and cells were blocked with 10% donkey serum in PBS for 30 min. For differential staining of external and internalized IgG- or C3bi-opsonized RBC, cells were incubated with Alexa™488-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit antibodies, permeabilized with 0.5% Triton for 10 min and incubated with Rhodamine-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit antibodies. Coverslips were mounted in Pro-Long antifade reagent (Invitrogen) and analysed using a ZEISS Axioimager fluorescence microscope. Binding and phagocytosis indices were determined by counting the number of RBC, respectively, associated to and internalized by a minimum of 50 cells, be they J774A.1 macrophages, FcγR- or CR3-transfected Cos-7 cells.

EHEC phagocytosis

EHEC bacterial strains expressing the GFP-encoding pFPV25.1 plasmid were used (see Table 1). Overnight cultures were diluted 1/100 in SFM supplemented with 25 mM Hepes and the appropriate antibiotic, then added onto J774.A1 macrophages for 4 h at 37°C. Cells were fixed and incubated successively with goat anti-EHEC O157:H7 IgG (Fitzgerald) then Texas red-conjugated donkey anti-goat IgG, to stain extracellular EHEC in red. Cells were then permeabilized, F-actin was labelled red, using Rhodamine RedX-coupled phalloidin (Molecular Probes), and coverslips were mounted on Mowiol (Calbiochem). The numbers of bacteria bound (red) and internalized (green) were scored using an epifluorescence microscope (BX50, Olympus). The levels of phagocytosis measured for wild-type and ΔescN EHEC were equivalent for the 85-170 and EDL-933 EHEC strains.

All data were analysed by unpaired, two-tailed Student's t-test, and considered statistically significant for P < 0.05.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jim Kaper for the kind gift of strain MK41. This work was funded by EIMID, the European Initiative for basic research in Microbiology and Infectious Disease (through a Marie Curie Studentship to V.C.) and by grants from the Wellcome Trust and from the Biotechnology and the Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC).

References

- Allen LA, Aderem A. Molecular definition of distinct cytoskeletal structures involved in complement- and Fc receptor-mediated phagocytosis in macrophages. J Exp Med. 1996;184:627–637. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.2.627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, Niedergang F. Linking exocytosis and endocytosis during phagocytosis. Biol Cell. 2006;98:195–201. doi: 10.1042/BC20050021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, Fraisier V, Raposo G, Hurbain I, Sibarita JB, Chavrier P, et al. TI-VAMP/VAMP7 is required for optimal phagocytosis of opsonised particles in macrophages. EMBO J. 2004;23:4166–4176. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caron E, Hall A. Identification of two distinct mechanisms of phagocytosis controlled by different Rho GTPases. Science. 1998;282:1717–1721. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5394.1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caron E, Self AJ, Hall A. The GTPase Rap1 controls functional activation of macrophage integrin alpha M beta 2 by LPS and other inflammatory mediators. Curr Biol. 2000;10:974–978. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00641-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caron E, Crepin VF, Simpson N, Knutton S, Garmendia J, Frankel G. Subversion of actin dynamics by EPEC and EHEC. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2006;9:40–45. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2005.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celli J, Olivier M, Finlay BB. Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli mediates antiphagocytosis through the inhibition of PI 3-kinase-dependent pathways. EMBO J. 2001;20:1245–1258. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.6.1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaves-Olarte E, Low P, Freer E, Norlin T, Weidmann M, von Eichel-Streiber C, Thelestam M. A novel cytotoxin from Clostridium difficile serogroup F is a functional hybrid between two other large clostridial cytotoxins. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:11046–11052. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.16.11046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collington GK, Booth IW, Donnenberg MS, Kaper JB, Knutton S. Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli virulence genes encoding secreted signalling proteins are essential for modulation of Caco-2 cell electrolyte transport. Infect Immun. 1998;66:6049–6053. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.12.6049-6053.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coombes BK, Valdez Y, Finlay BB. Evasive manoeuvres by secreted bacterial proteins to avoid innate immune responses. Curr Biol. 2004;14:R856–R867. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cougoule C, Hoshino S, Dart A, Lim J, Caron E. Dissociation of recruitment and activation of the small G-protein Rac during Fcgamma receptor-mediated phagocytosis. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:8756–8764. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513731200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane JK, McNamara BP, Donnenberg MS. Role of EspF in host cell death induced by enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Cell Microbiol. 2001;3:197–211. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2001.00103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahan S, Wiles S, La Ragione RM, Best A, Woodward MJ, Stevens MP, et al. EspJ is a prophage-carried type III effector protein of attaching and effacing pathogens that modulates infection dynamics. Infect Immun. 2005;73:679–686. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.2.679-686.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. One-step inactivation of chromosomal in Escherichia coli K12 using PCR products. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:6640–6645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120163297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon E, Duclos S, Rondeau C, Chevet E, Cameron PH, Steele-Mortimer O, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum-mediated phagocytosis is a mechanism of entry into macrophages. Cell. 2002;110:119–131. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00797-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garmendia J, Phillips AD, Carlier MF, Chong Y, Schuller S, Marchès O, et al. TccP is an enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 type III effector protein that couples Tir to the actin-cytoskeleton. Cell Microbiol. 2004;6:1167–1183. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2004.00459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garmendia J, Frankel G, Crepin VF. Enteropathogenic and enterohaemorrhagic E. coli infections: translocation, translocation, translocation. Infect Immun. 2005;73:2586–2594. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.5.2573-2585.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giammanco GM, Pignato S, Mammina C, Grimont F, Grimont PA, Nastasi A, et al. Persistent endemicity of Salmonella bongori 48:z(35):– Southern Italy: molecular characterization of human, animal, and environmental isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:3502–3505. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.9.3502-3505.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goosney DL, Celli J, Kenny B, Finlay BB. Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli inhibits phagocytosis. Infect Immun. 1999;67:490–495. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.2.490-495.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruenheid S, Sekirov I, Thomas NA, Deng W, O'Donnell P, Goode D, et al. Identification and characterization of NleA, a non-LEE-encoded type III translocated virulence factor of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. Mol Microbiol. 2004;51:1233–1249. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardwidge PR, Deng W, Vallance BA, Rodriguez-Escudero I, Cid VJ, Molina MF, et al. Modulation of host cytoskeleton function by the enteropathogenic Escherichia coli and Citrobacter rodentium effector protein EspG. Infect Immun. 2005;73:2586–2594. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.5.2586-2594.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inman LR, Cantey JR. Specific adherence of Escherichia coli (strain RDEC-1) to membranous (M) cells of the Peyer's patch in Escherichia coli diarrhea in the rabbit. J Clin Invest. 1983;71:1–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI110737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe AB, Hall A. Rho GTPases: biochemistry and biology. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2005;21:247–269. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.020604.150721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis KG, Giron JA, Jerse AE, McDaniel TK, Donnenberg MS, Kaper JB. Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli contains a putative type III secretion system necessary for the export of proteins involved in attaching and effacing lesion formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7996–8000. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerse AE, Yu J, Tall BD, Kaper JB. A genetic locus of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli necessary for the production of attaching and effacing lesions on tissue culture cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:7839–7843. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.20.7839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Just I, Selzer J, Wilm M, von Eichel-Streiber C, Mann M, Aktories K. Glucosylation of Rho proteins by Clostridium difficile toxin B. Nature. 1995;375:500–503. doi: 10.1038/375500a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanack KJ, Crawford JA, Tatsuno I, Karmali MA, Kaper JB. SepZ/EspZ is secreted and translocated into HeLa cells by the enteropathogenic Escherichia coli type III secretion system. Infect Immun. 2005;73:4327–4337. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.7.4327-4337.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaper JB, Nataro JP, Mobley HL. Pathogenic Escherichia coli. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:123–140. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny B, DeVinney R, Stein M, Reinscheid DJ, Frey EA, Finlay BB. Enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC) transfers its receptor for intimate adherence into mammalian cells. Cell. 1997;91:511–520. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80437-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny B, Ellis S, Leard AD, Warawa J, Mellor H, Jepson MA. Co-ordinate regulation of distinct host cell signalling pathways by multifunctional enteropathogenic Escherichia coli effector molecules. Mol Microbiol. 2002;44:1095–1107. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02952.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutton S, Lloyd DR, McNeish AS. Adhesion of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli to human intestinal enterocytes and cultured human intestinal mucosa. Infect Immun. 1987;55:69–77. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.1.69-77.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine MM, Berquist EJ, Nalin DR, Waterman DH, Hornick RB, Young CR, et al. Escherichia coli that cause diarrhoea but do not produce heat-labile or heat-stable enterotoxins and are non-invasive. Lancet. 1978;27:1119–1122. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(78)90299-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel TK, Jarvis KG, Donnenberg MS, Kaper JB. A genetic locus of enterocyte effacement conserved among diverse enterobacterial pathogens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:1664–1668. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNamara BP, Koutsouris A, O'Connell CB, Nougayrède JP, Donnenberg MS, Hecht G. Translocated EspF protein from enteropathogenic Escherichia coli disrupts host intestinal barrier function. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:621–629. doi: 10.1172/JCI11138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchès O, Wiles S, Dziva F, La Ragione RM, Schuller S, Best A, et al. Characterization of two non-locus of enterocyte effacement-encoded type III-translocated effectors, NleC and NleD, in attaching and effacing pathogens. Infect Immun. 2005;73:8411–8417. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.12.8411-8417.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchès O, Batchelor M, Shaw RK, Patel A, Cummings N, Nagai T, et al. EspF of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli binds sorting nexin 9. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:3110–3115. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.8.3110-3115.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Argudo I, Sands C, Jepson MA. Translocation of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli across an in vitro M cell model is regulated by its type III secretion system. Cell Microbiol. 2007;9:1538–1546. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.00891.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzawa T, Kuwae A, Yoshida S, Sasakawa C, Abe A. Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli activates the RhoA signaling pathway via the stimulation of GEF-H1. EMBO J. 2004;23:3570–3582. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundy R, Petrovska L, Smollett K, Simpson N, Wilson RK, Yu J, et al. Identification of a novel Citrobacter rodentium type III secreted protein, EspI, and roles of this and other secreted proteins in infection. Infect Immun. 2004;72:2288–3302. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.4.2288-2302.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai T, Abe A, Sasakawa C. Targeting of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli EspF to host mitochondria is essential for bacterial pathogenesis: critical role of the 16th leucine residue in EspF. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:2998–3011. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411550200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niedergang F, Chavrier P. Regulation of phagocytosis by Rho GTPases. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2005;291:43–60. doi: 10.1007/3-540-27511-8_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nougayrède JP, Donnenberg MS. Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli EspF is targeted to mitochondria and is required to initiate the mitochondrial death pathway. Cell Microbiol. 2004;6:1097–1111. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2004.00421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochman H, Groisman EA. Distribution of pathogenicity islands in Salmonella spp. Infect Immun. 1996;64:5410–5412. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.12.5410-5412.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel JC, Hall A, Caron E. Vav regulates activation of Rac but not Cdc42 during FcgammaR-mediated phagocytosis. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:1215–1226. doi: 10.1091/mbc.02-01-0002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips AD, Navabpour S, Hicks S, Dougan G, Wallis T, Frankel G. Enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 target Peyer's patches in humans and cause attaching/effacing lesions in both human and bovine intestine. Gut. 2000;47:377–381. doi: 10.1136/gut.47.3.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quitard S, Dean P, Maresca M, Kenny B. The enteropathogenic Escherichia coli EspF effector molecule inhibits PI-3 kinase-mediated uptake independently of mitochondrial targeting. Cell Microbiol. 2006;8:972–981. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00680.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid SD, Herbelin CJ, Bumbaugh AC, Selander RK, Whittam TS. Parallel evolution of virulence in pathogenic Escherichia coli. Nature. 2000;406:64–67. doi: 10.1038/35017546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rottner K, Stradal TE, Wehland J. Bacteria–host-cell interactions at the plasma membrane: stories on actin cytoskeleton subversion. Dev Cell. 2005;9:3–17. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlosser-Silverman E, Elgrably-Weiss M, Rosenshine I, Kohen R, Altuvia S. Characterization of Escherichia coli DNA lesions generated within J774 macrophages. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:5225–5230. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.18.5225-5230.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw RK, Cleary J, Frankel G, Knutton S. Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli interaction with human intestinal mucosa: role of effector proteins in brush border remodelling and ‘attaching & effacing’ lesion formation. Infect Immun. 2005a;73:1243–1251. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.2.1243-1251.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw RK, Smollett K, Cleary J, Garmendia J, Straatman-Iwanowska A, Frankel G, et al. Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli type III effectors EspG and EspG2 disrupt the microtubule network of intestinal epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 2005b;73:4385–4390. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.7.4385-4390.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson N, Shaw R, Crepin VF, Mundy R, Fitzgerald AJ, Cummings N, et al. The enteropathogenic Escherichia coli type III secretion system effector Map binds EBP50/NHERF1: implication for cell signalling and diarrhoea. Mol Microbiol. 2006;60:349–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spears KJ, Roe AJ, Gally DL. A comparison of enteropathogenic and enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli pathogenesis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2006;255:187–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens MP, Roe AJ, Vlisidou I, Van Diemen PM, La Ragione RM, Best A, et al. Mutation of toxB and a truncated version of the efa-1 gene in Escherichia coli O157:H7 influences the expression and secretion of locus of enterocyte effacement-encoded proteins but not intestinal colonization in calves or sheep. Infect Immun. 2004;72:5402–5411. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.9.5402-5411.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobe T, Beatson SA, Taniguchi H, Abe H, Bailey CM, Fivian A, et al. An extensive repertoire of type III secretion effectors in Escherichia coli O157 and the role of lambdoid phages in their dissemination. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:14941–14946. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604891103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomson FL, Viswanathan VK, Kanack KJ, Kanteti RP, Straub KV, Menet M, et al. Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli EspG disrupts microtubules and in conjunction with Orf3 enhances perturbation of the tight junction barrier. Mol Microbiol. 2005;56:447–464. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdivia RH, Falkow S. Bacterial genetics by flow cytometry: rapid isolation of Salmonella typhimurium acid-inducible promoters by differential fluorescence induction. Mol Microbiol. 1996;22:367–378. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.00120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterman SR, Holden DW. Functions and effectors of the Salmonella pathogenicity island 2 type III secretion system. Cell Microbiol. 2003;5:501–511. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2003.00294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiles S, Clare S, Harker J, Huett A, Young D, Dougan G, Frankel G. Organ specificity, colonization and clearance dynamics in vivo following oral challenges with the murine pathogen Citrobacter rodentium. Cell Microbiol. 2004;6:963–972. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2004.00414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]