Abstract

In cycling cells, the retinoblastoma protein (pRb) is un- and/or hypo-phosphorylated in early G1 and becomes hyper-phosphorylated in late G1. The role of hypo-phosphorylation and identity of the relevant kinase(s) remains unknown. We show here that hypo-phosphorylated pRb associates with E2F in vivo and is therefore active. Increasing the intracellular concentration of the Cdk4/6 specific inhibitor p15INK4b by transforming growth factor β treatment of keratinocytes results in G1 arrest and loss of hypo-phosphorylated pRb with an increase in unphosphorylated pRb. Conversely, p15INK4b-independent transforming growth factor β-mediated G1 arrest of hepatocellular carcinoma cells results in loss of Cdk2 kinase activity with continued Cdk6 kinase activity and pRb remains only hypo-phosphorylated. Introduction of the Cdk4/6 inhibitor p16INK4a protein into cells by fusion to a protein transduction domain also prevents pRb hypo-phosphorylation with an increase in unphosphorylated pRb. We conclude that cyclin D:Cdk4/6 complexes hypo-phosphorylate pRb in early G1 allowing continued E2F binding.

Progression of normal human cells into malignant ones involves the genetic alteration of several classes of genes, including protooncogenes (positive regulators), tumor suppressor genes (negative regulators), and DNA damage repair genes. Alteration of these genes appears to result in the loss of negative control of the late G1 restriction point and, hence, uncontrolled proliferation (1–3). Recent work has pieced together an important G1 phase cell cycle regulatory pathway involving the INK4 kinase inhibitors, p15INK4b, p16INK4a, p18INK4c, and p19INK4d, that negatively regulate complexes of cyclin D1, D2, and D3 bound to Cdk4 or Cdk6 (referred to herein as cyclin D:Cdk4/Cdk6 complexes) that phosphorylate the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor gene product (pRb) (2–4). pRb is an active transcriptional repressor when bound to transcription factors, such as members of the E2F family (5–10). Inactivation of pRb by hyper-phosphorylation in late G1 phase causes the release of E2F, allowing transcription of genes important for DNA synthesis (11). Genetic alteration of this pathway, such as inactivation of either p16INK4a or pRb, or amplification of cyclin D1 or Cdk4, occurs in a large number of human malignancies (12). However, there appears to be no oncogenic selective advantage in mutating any two of these genes, suggesting the involvement of these genes in a linear pathway (3, 12). Therefore, it is critical to understand the exact physiological functioning of these gene products in this pathway.

pRb exists in three general forms: unphosphorylated pRb, present in G0 cells and when pRb is newly synthesized; hypo-phosphorylated pRb, present in contact-inhibited cells and in early G1; and hyper-phosphorylated pRb, that is inactive and present in late G1, S, G2, and M phases of cycling cells (13, 14). Thus in cycling cells, pRb alternates between a hypo-phosphorylated form present in early G1 to a hyper-phosphorylated form after passage through the restriction point in late G1 and continued through S, G2, M, phases. The role of hypo-phosphorylated pRb in early G1 has not been determined. In addition, the identity of the cyclin:Cdk complex(es) that converts unphosphorylated pRb to hypo-phosphorylated pRb has not yet been determined. Although the presence of cyclin D:Cdk4/6 complexes in early G1 of cycling cells suggests that these complexes are likely candidates to hypo-phosphorylate pRb (14–16), reports based on overexpression systems and in vitro kinase assays have been interpreted to conclude that cyclin D:Cdk4/6 complexes are responsible for inactivating pRb by hyper-phosphorylation in late G1. However, these overexpression conditions are not necessarily reflective of physiological levels and/or activities of cyclin D:Cdk4/6 complexes in vivo.

We chose to investigate the role of pRb hypo-phosphorylation and to identify the physiologically relevant cyclin:Cdk complex(es) utilizing pRb as an in vivo substrate. We manipulated the cellular environment by addition of transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) to cycling and contact inhibited cells and by a novel method of transducing full length p16INK4a protein directly into cells. We report here that cyclin D:Cdk4/6 complexes hypo-phosphorylate pRb and that hypo-phosphorylated pRb associates with E2F transcription factors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture and Flow Cytometry Analysis.

HaCaT human keratinocytes and HepG2 human hepatocellular carcinoma cells (ATCC) were maintained in α-minimal essential medium (MEM), and Jurkat T cells (ATCC) in RPMI 1640 medium plus 10% bovine fetal serum, penicillin, and streptomycin in 5% CO2 at 37°C. TGF-β (R & D Systems) was added to a final concentration of 10 ng/ml to low density (2 × 106) or high density (8 × 106 cells per 10-cm dish) cultures. Cells were washed with PBS(−), fixed in −20°C 70% ethanol, and rehydrated with PBS(−) containing 0.1% BSA, RNase A (1 μg/ml), and propidium iodide (10 μg/ml) for 20 min prior to analysis on FACScan (Becton Dickinson). Cells (1 × 104) were counted and analyzed for cell cycle position using modfit lt software.

Labeling and Immunoprecipitations.

Cells were labeled in the presence of TGF-β or TAT-p16 proteins for 5 hr with 3–5 mCi (1 Ci = 37 GBq) [32P]orthophosphate (ICN) per 10-cm dish in 3.5 ml phosphate-free MEM supplemented with 10% dialyzed serum or with 250 μCi [35S]methionine (NEN) in 3.5 ml methionine minus MEM with 10% dialyzed serum. Cells were lysed in situ by the addition of 1 ml of E1A lysis buffer [ELB: 50 mM Hepes, pH 7.2/250 mM NaCl/2 mM EDTA/0.1% Nonidet P-40/1 mM DTT/1 μg/ml aprotinin (Sigma)/1 μg/ml leupeptin (Sigma)/50 μg/ml phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (Sigma)/0.5 mM NaP2O7/0.1 mM NaVO4/5.0 mM NaF]. Cellular lysates were precleared with killed Staphylococcus aureus cells (Zymed), and pRb was immunoprecipitated by addition of 5 μl G99–549 anti-pRb antibodies (PharMingen) that recognize only the fast migrating, un- and hypo-phosphorylated forms of pRb (17) or 400 μl of anti-E2F-4 monoclonal antibody tissue culture supernatant (K. Moberg and J. A. Lees, Massachusetts Institute of Technology). A total of 0.5 μg polyclonal rabbit anti-Cdk6 and anti-p16 antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were used under the same conditions. Immune complexes were collected on protein A Sepharose (Pharmacia), washed three times with 1 ml ELB, boiled in SDS buffer, resolved by SDS/PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose filters, exposed to storage PhosphorImager screens (Kodak), and analyzed on a Storm PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics). For secondary immunoprecipitation, samples were cooled after boiling, diluted 1:30 with ELB, clarified of protein A Sepharose beads, and immunoprecipitated as described above using twice the amount of antibodies. Nitrocellulose filters after exposure to PhosphorImager screen were blocked in 5% nonfat milk in PBS(−)/0.2% Tween for 30 min and incubated with monoclonal anti-pRb antibodies G3–349 (PharMingen) for 2 hr, washed three times in PBS(−)/0.2% Tween, probed with secondary rabbit anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibodies (The Jackson Laboratories) for 1 hr, washed, and developed by addition of ECL reagent (Amersham).

Kinase Assay and Reverse Transcription–PCR.

Anti-Cdk2 or anti-Cdk6 immunoprecipitates were washed three times with ELB followed by final wash with kinase buffer (50 mM Hepes, pH 7.0/10 mM MgCl2/1 mM DTT/1 μM unlabeled ATP) and suspended in 25 μl of kinase buffer plus 100 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP (Amersham; 6,000 Ci/mmol) and 2 μg of freshly prepared (C. Sherr, personal communication) glutathione S-transferase (GST)–C′–pRb [residues 792–928 (18)] for Cdk6 kinase reaction, 10 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP and 2 μg of histone H1 (Sigma) for Cdk2 kinase reaction. Reactions were incubated for 30 min at 30°C, stopped by addition of 2× SDS buffer, separated on SDS/PAGE, and analyzed by PhosphorImager screen (Kodak) exposure and analysis (Molecular Dynamics). Equal amounts of rabbit anti-mouse antibodies were used as negative controls.

cDNA synthesis from total RNA was performed using Perkin–Elmer RT-PCR kit with oligo(dT) primers. Amplification of p15 and cyclin E cDNA was performed in 50 μl reaction using 1 μg of cDNA and 20 pmol of p15-5′ (5′-GGAAGAGTGTCGTTAAGTTTACG-3′)/p15-3′ (5′-GTTGGCAGCCTTCATCGAAT-3′) primers and cyclin E-5′ (5′-GCAGGATCCAGATGAAGA-3′)/cyclin E-3′ (5′-CTTGTGTCGCCATATACCGGTC-3′) in 50 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 8.3), 200 μM dNTPs, 2 mM MgCl2, 10% dimethyl sulfoxide, and 2.5 units Taq polymerase (Perkin–Elmer) for 35 cycles at 94°C for 1 min, 49°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min. A final extension of 5 min was carried out at 72°C. PCR products were resolved on a 2% agarose gel and visualized with ethidium bromide staining.

Two-Dimensional Phosphopeptide Map Analysis.

pRb was immunoprecipitated with G-99 antibodies from [32P]orthophosphate-labeled control or TGF-β-treated HaCaT cells, separated by SDS/PAGE, and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and the 32P-labeled pRb band was visualized by ARG film (Kodak). The 32P-labeled pRb section was digested with trypsin essentially as described (19). Phosphopeptides were loaded onto thin-layer cellulose (TLC) plates (Baker-flex/VWR Scientific), separated in the first dimension by electrophoresis on a Multiphor II (Pharmacia), followed by second dimension separation TLC for ≈7 hr in TLC buffer (75 ml n-butanol/50 ml pyridine/15 ml glacial acetic acid/60 ml H2O). TGF-β and control samples were loaded based on approximately equal cpm of 32P and not moles of pRb.

Plasmid Construction and Protein Expression.

pTAT-p16 wild-type and mutant (R87P) vectors were generated by inserting a NcoI–EcoRI fragment from p16 cDNAs obtained from Parry and Peters (20) into the pTAT vector (A.V.A. and S.F.D., unpublished data). TAT-p16 proteins were purified by sonication of high-expressing BL21(DE3)pLysS (Novagen) cells from a 1 liter culture in 10 ml of buffer A (8 M urea/20 mM Hepes. pH 7.0/100 mM NaCl). Cellular lysates were resolved by centrifugation, loaded onto a 5 ml Ni-NTA column (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA) in buffer A containing 20 mM imidazole and eluted by increasing imidazole concentration followed by dialysis against 20 mM Hepes/150 mM NaCl. Purified TAT-p16 protein was added to a final concentration of 100–300 nM to cells in complete medium. Fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled TAT-p16 proteins were generated by fluorescein labeling (Pierce), followed by gel purification on a S-12 column attached to FPLC (Pharmacia).

RESULTS

Hypo-phosphorylated pRb Interacts with E2F in Vivo.

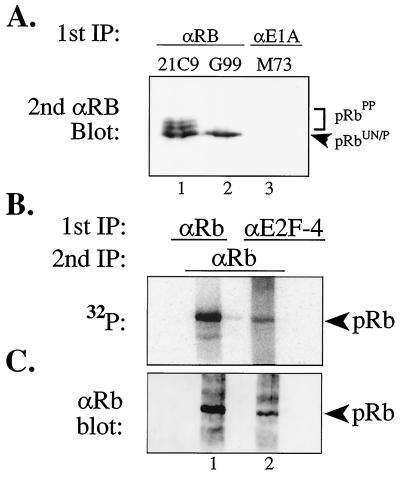

To understand the physiological role of hypo-phosphorylated pRb, we first sought to determine if hypo-phosphorylated pRb associated with cellular transcription factors, such as members of the E2F family. Previous work has shown that pRb forms physical complexes with E2F (5–9); however, it has not been shown if E2F family members interact with un- and/or hypo-phosphorylated pRb. To do so, 1 × 108 cycling HaCaT cells were labeled with 100 mCi of [32P]orthophosphate for 5 hr, E2F-4:pRb complexes were immunoprecipitated from cellular lysates with anti-E2F-4 antibodies (90% of total lysate) (21) and pRb (10% of total lysate) was immunoprecipitated by using conformation-dependent anti-pRb antibodies (G99) that selectively recognize un- and hypo-phosphorylated pRb that represent the fastest migrating form of pRb on SDS/PAGE (Fig. 1A, lane 2) (17). The primary immune complexes were washed, boiled, diluted, and re-immunoprecipitated with polyclonal anti-pRb antibodies. Secondary immune complexes were resolved by SDS/PAGE, transferred to a filter, and analyzed for 32P content (Fig. 1B). To normalize for pRb protein levels between anti-E2F-4 and anti-pRb immunoprecipitates, the same filter was then probed with anti-pRb antibodies (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1.

E2F-4 interacts with hypo-phosphorylated pRb in vivo. (A) Antibody controls of immunoprecipitated and immunoblotted pRb from asynchronously cycling HaCat cells using 21C9 anti-pRb antibodies that recognize all forms of pRb (lane 1), conformational specific G99 anti-pRb antibodies that recognize only the fastest migrating, un- and hypo-phosphorylated pRb forms (lane 2), and nonspecific control M73 anti-E1A antibodies (lane 3). Please note the complete absence of immunoprecipitated pRb in lane 3 (HaCaT cells do not express E1A). (B and C) HaCaT human keratinocytes (1 × 108) were labeled with 100 mCi [32P]orthophosphate and primary immunoprecipitation was performed with either anti-E2F-4 (90% of total lysate) or with G99 anti-pRb (10% of total lysate) antibodies followed by secondary immunoprecipitation with rabbit anti-pRb antibodies, resolved by SDS/PAGE, transferred to a filter, and analyzed for 32P content (B) and then probed with anti-pRb antibodies to normalize for pRb protein levels (C).

The coimmunoprecipitation of 32P-labeled hypo-phosphorylated pRb with E2F-4 was readily detectable (Fig. 1B) whereas nonspecific control antibodies failed to immunoprecipitate pRb (Fig. 1A). Approximately 5% of the total amount of hypo-phosphorylated pRb found in anti-pRb immunoprecipitates was present in these E2F-4:pRb complexes (Fig. 1C). The ratio of 32P content to pRb protein was not altered between direct anti-pRb immunoprecipitates and anti-E2F-4 coimmunoprecipitated pRb. This finding indicates that E2F-4 does not selectively interact with a subset of hypo-phosphorylated pRb forms containing a different molar ratio of phosphate per molecule of pRb compared with the total hypo-phosphorylated pRb forms. In addition, we detect 32P-labeled hypo-phosphorylated pRb in complex with E2F-1 from HaCat, HT1080 fibrosarcoma cells, and leukemic Jurkat T cells (data not shown). Moreover, this finding is consistent with the observation that viral oncoproteins such as simian virus 40 T Ag and adenovirus E1A sequester 32P-labeled hypo-phosphorylated pRb (ref. 22; unpublished data). These results demonstrate for the first time that hypo-phosphorylated pRb interacts with members of the E2F transcription factor family in vivo and support the notion that hypo-phosphorylated pRb is active.

pRb Hypo-phosphorylation Is Inhibited in TGF-β-Treated Cells.

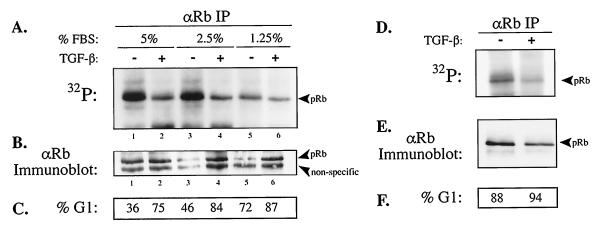

Given the importance of E2F:pRb complexes in regulation of G1 to S phase cell cycle progression, we next sought to uncover the in vivo cyclin:Cdk complex(es) that hypo-phosphorylate pRb. TGF-β treatment of HaCaT keratinocytes has previously been shown to result in a G1-specific arrest, induction of the Cdk4/6 inhibitor p15INK4b, loss of hyper-phosphorylated pRb, and appearance of the fastest migrating form of pRb on SDS/PAGE (23, 24). However, due to the comigration of un- and hypo-phosphorylated pRb species as the fastest form on SDS/PAGE, the phosphorylation status of pRb in TGF-β-treated cells was not determined. Therefore, we treated cells with TGF-β, labeled pRb in vivo with [32P]orthophosphate, and immunoprecipitated pRb with G99 conformation-dependent anti-pRb antibodies. This approach allowed for the comparison of pRb hypo-phosphorylation levels in untreated, proliferating control cells (that contain hypo- and hyper-phosphorylated forms of pRb) to cells treated with TGF-β. A gradual reduction in pRb hypo-phosphorylation and an accumulation of cells in G1 was observed in untreated cultures with decreasing serum concentration (Fig. 2 A and C), consistent with the previously reported growth factor dependency of cyclin D1 expression (25). However, we observed a dramatic reduction in pRb hypo-phosphorylation in TGF-β-treated cells, whereas pRb protein levels remained relatively constant between TGF-β-treated and control cultures. These results suggested a TGF-β-dependent negative regulation of pRb hypo-phosphorylating cyclin:Cdk complex(es).

Figure 2.

TGF-β treatment of cycling and contact inhibited G1-arrested HaCaT cells results in a reduction in the amount of in vivo hypo-phosphorylation of pRb. (A–C) Low-density asynchronous cycling and (D–F) high density contact-inhibited G1-arrested HaCaT cells were treated with TGF-β for 36 hr, labeled with [32P]orthophosphate, and immunoprecipitated with G99 anti-pRb antibodies that recognize the fastest migrating forms of pRb. Immune complexes were resolved by SDS/PAGE, transferred to a filter, and analyzed for 32P content (A and D) and then the same filter was probed with anti-pRb antibodies (B and E) to normalize for pRb protein levels as indicated. (C and F) Percentage of cells in G1 determined by FACS analysis.

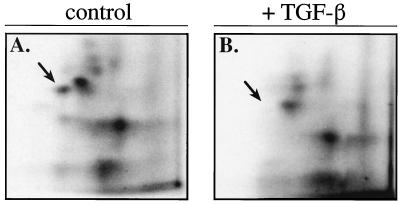

To ascertain whether loss of pRb hypo-phosphorylation was specific to TGF-β signaling or merely an outcome of G1 phase arrest, we labeled with [32P]orthophosphate contact-inhibited, G1-arrested HaCaT cells in 10% fetal bovine serum and immunoprecipitated pRb with G99 antibodies. Despite the equality of G1-arrested HaCaT cells, a further reduction in pRb hypo-phosphorylation in TGF-β-treated cells compared with untreated control cells was observed (Fig. 2D). pRb contains 16 putative Cdk consensus phosphorylation sites (26). To examine whether TGF-β-dependent loss of pRb hypo-phosphorylation was restricted to a limited number of phosphorylation sites or if it was a global loss, immunoprecipitated pRb from 32P-labeled lysates of TGF-β treated and control HaCaT cells were analyzed by two-dimensional tryptic phosphopeptide mapping (18). Comparison of the pRb phosphopeptide maps from control and TGF-β-treated HaCaT cells from cycling or contact inhibited cells revealed the apparent loss of a single tryptic phosphopeptide species (see arrow) in TGF-β-treated cells (Fig. 3; data not shown). In addition, the G99 immunoprecipitated pRb phosphopeptide maps from cycling and contact inhibited cells are nearly identical (data not shown). The loss of this single pRb tryptic phosphopeptide species, although interesting per se, cannot account for the observed overall reduction of pRb hypo-phosphorylation in TGF-β treated cells. Thus, loss of hypo-phosphorylated pRb is specific to TGF-β signaling and not merely an outcome of G1 phase cell cycle arrest.

Figure 3.

TGF-β treatment of HaCaT cells results in the loss of a single tryptic phosphopeptide species detected on the remaining low level of hypo-phosphorylated pRb species. Two-dimensional tryptic phosphopeptide mapping of in vivo [32P]orthophosphate-labeled pRb from G99 anti-pRb immune complexes from low density control (A) and TGF-β-treated (B) cultures of HaCaT cells. Arrow indicates the loss of a phosphorylated pRb tryptic peptide. TGF-β and control samples were loaded based on approximately equal cpm of 32P and not moles of pRb

Direct Transduction of p16 Protein into Cells Inhibits pRb Hypo-phosphorylation.

TGF-β treatment of responsive cells results in a wide array of effects (27); therefore, to focus on cyclin D:Cdk4/6 functioning in vivo and exclude additional TGF-β-regulated pathways, we chose to inactivate cyclin D:Cdk4/6 complexes directly by transduction of full-length p16INK4a protein into cells. Both p15INK4b and p16INK4a have previously been shown to bind specifically to Cdk4/6 (28). Several groups have described the ability of HIV-1 Tat protein to transduce into cells by crossing the cell membrane (29, 30) and Fawell et al. (31) expanded on its utility. However, no in-frame expression system to produce and transduce full-length proteins utilizing this technology has been subsequently developed. Therefore, we constructed a bacterial expression vector containing the minimal 11 amino acid Tat protein transduction domain, named pTAT, and fused it in-frame to wild-type and mutant (R87P) human p16INK4a cDNAs. pTAT-p16WT/MUT vectors allow for the production and purification of full-length TAT-p16 fusion proteins from bacteria (Fig. 4A). Addition of fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated wild-type and mutant TAT-p16 protein to p16(−) Jurkat T cells demonstrated the rapid entry into greater than 99% of cells, achieving maximum intracellular concentrations within 30 min as measured by fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis and confocal microscopy (unpublished data).

Figure 4.

Transduction of full-length p16 protein directly into cells results in loss of pRb hypo-phosphorylation. (A) Comparison of purity and concentration of bacterially expressed wild-type and mutant TAT-p16 purified fusion proteins by Coomassie blue staining. (B) High-density 36-hr contact-inhibited HaCaT cells were replated at low density and treated with either wild-type or mutant TAT-p16 protein at a final concentration of 300 nM. Cells were analyzed for cell cycle position by FACS at 30-hr postreplating. (C) p16INK4a(−) Jurkat T cells were transduced with either wild-type or mutant TAT-p16 protein, labeled with [35S]methionine, and immunoprecipitated with anti-p16 antibodies, then re-immunoprecipitated with anti-Cdk6 antibodies and resolved by SDS/PAGE. The position of Cdk6 is indicated. (D and E) Wild-type and mutant TAT-p16 proteins were added to high density 36-hr contact-inhibited HaCaT cells for 1 hr and then [32P]orthophosphate labeled for 5 hr in the presence of TAT-p16. Cellular lysates were prepared and pRb was immunoprecipitated with G99 anti-pRb antibodies, transferred to a filter, exposed to a PhosphorImager screen for 32P content (D), and then the same filter was probed with anti-pRb antibodies (E) to normalize for pRb protein levels.

Transient transfection of proliferating cells with p16INK4a encoding expression plasmids has been shown to result in G1 arrest and loss of pRb hyper-phosphorylation (32–34). To test the ability of TAT-p16 protein to elicit a G1-specific arrest, contact-inhibited HaCaT cells in 10% fetal bovine serum were replated at low density in the presence of 300 nM wild-type or mutant TAT-p16 protein and analyzed for cell cycle progression by FACS analysis at 30 hr postreplating (Fig. 4B). Untreated control and mutant TAT-p16 protein-treated HaCaT cells progressed into S phase; however, the addition of wild-type TAT-p16 protein to cells resulted in a G1 arrest. To analyze the ability of wild-type TAT-p16 to bind Cdk6, we treated p16INK4a(−) Jurkat T cells with either wild-type or mutant TAT-p16 and labeled with [35S]methionine. Cellular lysates were prepared and TAT-p16 immunoprecipitated with anti-p16 antibodies followed by boiling in SDS buffer, dilution, and re-immunoprecipitation with anti-Cdk6 antibodies (Fig. 4C). The results showed that wild-type but not mutant TAT-p16 was capable of forming complexes with Cdk6 in vivo. Thus, bacterially produced wild-type and mutant TAT-p16 fusion proteins of ≈20 kDa can efficiently transduce into >99% of target cells and bind its cognate intracellular target.

To analyze the influence of accumulated TAT-p16 protein on pRb hypo-phosphorylation, contact inhibited HaCaT cells in 10% FBS were pretreated with wild-type or mutant TAT-p16 protein for 1 hr, followed by addition of [32P]orthophosphate for 4 hr. pRb was immunoprecipitated from cellular lysates with G99 anti-pRb antibodies, resolved by SDS/PAGE, transferred to a filter, and analyzed for pRb 32P content (Fig. 4D) and then normalized for pRb protein levels (Fig. 4E). Transduction of TAT-p16 wild-type protein into cells resulted in a dramatic reduction in pRb hypo-phosphorylation compared with cells treated with TAT-p16 mutant protein whereas pRb protein levels remained relatively constant. The further increased loss of pRb hypo-phosphorylation observed in cells transduced with TAT-p16 protein compared with TGF-β treatment likely reflects the ability to achieve a higher intracellular concentration of Cdk4/6 inhibitor TAT-p16 versus TGF-β induction of p15INK4b protein. Taken together, these results support the notion that cyclin D:Cdk4/6 complexes hypo-phosphorylate pRb in vivo.

p15INK4b-Independent, TGF-β-Mediated G1 Arrest Does Not Alter pRb Hypo-phosphorylation.

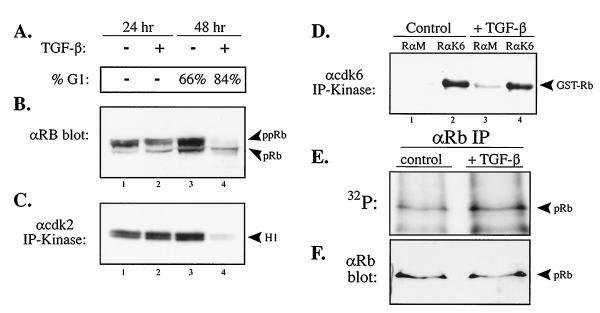

To further analyze the involvement of cyclin D:cdk4/6 complexes in hypo-phosphorylating pRb, we searched for a TGF-β-responsive cell line that arrests in G1, inactivates Cdk2, but retains Cdk6 kinase activity. We hypo-thesized that in such a cell type, pRb would remain hypo-phosphorylated upon TGF-β treatment. To this end, we found that treatment of human HepG2 hepatocellular carcinoma cells with TGF-β results in a G1 arrest as measured by propidium iodide staining and FACS analysis (Fig. 5A). Immunoblotting analysis of HepG2 cells treated with TGF-β revealed a loss of hyper-phosphorylated forms of pRb and the appearance of the fastest migrating pRb species, potentially consisting of both un- and hypo-phosphorylated forms (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

HepG2 hepatocellular carcinoma cells that arrest in G1 with TGF-β treatment in a p15INK4b-independent manner do not alter the in vivo hypo-phosphorylation of pRb. (A) DNA content by FACS analysis of asynchronous HepG2 cells treated with TGF-β for 48 hr. (B) Anti-pRb immunoblot analysis of control and TGF-β treated HepG2 cellular lysates with anti-pRb antibodies at 24 and 48 hr. (C) Anti-cdk2 and (D) anti-cdk6 and control rabbit anti-mouse IgG (RαM) immunoprecipitation-kinase assay from control and TGF-β treated HepG2 lysates using histone H1 and GST–RB–C′ as in vitro substrates, respectively. (E and F) Asynchronous HepG2 cells were treated with TGF-β for 48 hr, labeled in vivo with [32P]orthophosphate, and immunoprecipitated with G99 anti-pRb antibodies that recognize the fastest migrating forms of pRb. Immune complexes were resolved by SDS/PAGE, transferred to a filter, and analyzed for 32P content (E) and then the same filter was probed with anti-pRb antibodies (F) to normalize for pRb protein levels as indicated.

We next measured the effect of TGF-β signaling on Cdk2 and Cdk6 kinase activity in HepG2 cells. Anti-Cdk2 and anti-Cdk6 immunoprecipitation-kinase assays were performed on cellular lysates from control and TGF-β-treated HepG2 cells using histone H1 or GST–C′ terminus Rb as in vitro substrates, respectively (Fig. 5 C and D). Cdk2 activity was markedly diminished following 48 hr of TGF-β treatment in agreement with loss of pRb hyper-phosphorylation. In contrast, Cdk6 activity was not affected by TGF-β signaling (Fig. 4D). The continued Cdk6 activity in TGF-β-treated HepG2 cells is consistent with the failure of these cells to induce the Cdk4/6-specific inhibitor p15INK4b as measured by anti-p15 immunoprecipitation and p15 reverse transcription–PCR analyses (H.N. & S.F.D, unpublished data).

Finally, we analyzed the effect of TGF-β signaling on pRb hypo-phosphorylation in HepG2 cells. HepG2 cells were treated with TGF-β for 48 hr and labeled with [32P]orthophosphate, and pRb was immunoprecipitated from cellular lysates using G99 anti-pRb antibodies. The immune complexes were resolved by SDS/PAGE, transferred to a filter, and analyzed for pRb 32P content and then pRb protein levels (Fig. 5 E and F). The results showed no change in pRb hypo-phosphorylation levels between TGF-β-treated and control HepG2 cells. In addition, no changes were observed between the tryptic phosphopeptide maps of hypo-phosphorylated pRb obtained from control or TGF-β-treated HepG2 cells (data not shown).

Thus, in HepG2 cells, TGF-β can effect a G1 arrest by a previously unknown 15INK4b-independent pathway that retains cyclin D:Cdk6 kinase activity but negatively regulates Cdk2 kinase activity and pRb remains hypo-phosphorylated. This observation is consistent with a role for cyclin D:Cdk4/6 complexes in only hypo-phosphorylating pRb and not in its hyper-phosphorylation.

DISCUSSION

The loss of negative regulation of G1 phase cell cycle progression by inactivating mutation of p16INK4a or RB, or amplification of cyclin D1 or Cdk4 is a critical step in human oncogenesis and has therefore become an intense area of investigation. The previously held notion that cyclin D:Cdk4/6 complexes inactivate pRb by hyper-phosphorylation was based largely on cyclin D overexpression experiments, serum deprivation-addition experiments, and in vitro kinase assays using fragments of pRb as a substrate. Although these experiments are informative and reproducible, they do not appear to reflect the physiological roles of these complexes in vivo.

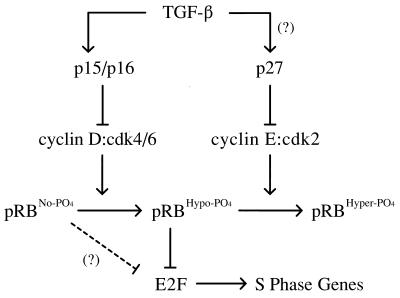

To solve this paradox and avoid potential artifacts from overexpression of activators like cyclin D1, we utilized pRb as an in vivo substrate and manipulated the activity of cyclin D:Cdk4/6 complex(es) by increasing the intracellular concentrations of cyclin D:Cdk4/6-specific inhibitors: p15INK4b through TGF-β treatment or p16 by direct transduction of TAT-p16 protein. We conclude that cyclin D:Cdk4/6 complexes only hypo-phosphorylate pRb and that hypo-phosphorylated pRb actively associates with E2F family members in vivo and is not “partially” inactive. Thus, given the role of cyclin D:Cdk4/6 complexes in hypo-phosphorylating pRb, we suggest it unlikely that cyclin D:Cdk4/6 complexes perform both the hypo-phosphorylation and the inactivating hyper-phosphorylation of pRb observed in late G1 that likely occurs by cyclin E:Cdk2 complexes (Fig. 6). Indeed, the presence of only hypo-phosphorylated pRb in TGF-β-treated HepG2 cells that contain active cyclin D:Cdk6 complexes but inactive cyclin E:Cdk2 complexes further solidifies this notion. Furthermore, the idea that cyclin D:Cdk4/6 complexes hyper-phosphorylate pRb would predict that in p16(−) tumor cells should contain inappropriately, constitutively hyper-phosphorylated pRb; however, pRb continues to alternate between hypo-phosphorylated in early G1 to hyper-phosphorylated forms in late G1, S, G2, and M phases in both p16(−) leukemic Jurkat T cells and p16(−) HT1080 fibrosarcoma cells, and continues to associate with E2F-1 and E2F-4 (ref. 14; unpublished observation).

Figure 6.

Model of p15/16, cyclin D:Cdk4/6, pRb, E2F pathway. Cyclin D:Cdk4/6 complexes associate with pRbs pocket domain and then proceed to hypo-phosphorylate pRb in early G1, and likely throughout the entire cell cycle. Hypo-phosphorylated pRb is active and binds to transcription factors, such as E2Fs. The initial hyper-phosphorylating inactivator of pRb is likely cyclin E:Cdk2 complexes expressed and activated at a position congruent with the passage through the late G1 restriction point. Hyper-phosphorylation of pRb results in the dissociation of E2Fs and subsequent activation of E2F-specific promoters, such as genes required for DNA synthesis. The presence of unphosphorylated pRb in TGF-β-treated wild-type cells and the apparent requirement of cyclin E:cdk complexes for prior hypo-phosphorylated pRb as an in vivo substrate (37) suggests that TGF-β signaling drives the cell further into a G0-like state.

Hypo-phosphorylation of pRb may serve the cell several purposes. First, hypo-phosphorylated pRb appears to be comprised of multiple isoforms that individually contain a combination of one or two phosphates on the 16 putative Cdk consensus sites (refs. 22, 35, and 36; unpublished observation). The generation of multiple isoforms of active hypo-phosphorylated pRb may target subsets of pRb to specific transcription factors and, hence, regulate specific promoters. As an example, in vitro mixing experiments of baculovirus produced hypo-phosphorylated pRb with E1A or E2F-1:DP-1 complexes demonstrates that E1A interacts with a larger subset of hypo-phosphorylated pRb isoforms then E2F-1:DP-1 complexes do as ascertained by two-dimensional phosphopeptide mapping (R. R. Latek and S.F.D., unpublished observation). Second, prior pRb hypo-phosphorylation by cyclin D1 appears required for subsequent pRb hyper-phosphorylation by cyclin E as has been shown in genetically engineered yeast cells (37). Thus, TGF-β-dependent loss of pRb hypo-phosphorylation may further remove pRb from becoming a substrate for inactivating hyper-phosphorylation by cyclin E:Cdk2 and thereby potentiate a stronger TGF-β-dependent G1 arrest, driving cells into G0.

The data presented here demonstrate that cyclin D:Cdk4/6 complexes perform the hypo-phosphorylation of pRb in vivo and thereby leaves open the question of how p16 or cyclin D1 genetic alterations contribute to oncogenic progression. Three mutually inclusive hypo-theses emerge. First, dysregulated cyclin D:Cdk4/6 complexes may place an inappropriate key phosphate(s) on pRb that inactivates its transcriptional repression abilities while allowing continued E2F association. Second, dysregulated cyclin D:Cdk4/6 complexes may prevent the appearance of unphosphorylated pRb and thereby prohibit the cell from entering a true G0 state, dependent on the presence of unphosphorylated pRb. Lastly, dysregulated cyclin D:Cdk4/6 complexes in tumors may lead to inappropriate phosphorylation of other (unknown) target protein substrates or activation of proteins by amplified cyclin D1 in a kinase-independent fashion (38). Future work on the types of pRb hypo-phosphorylated isoforms present in p16(−) or cyclin D1-amplified tumors compared with normal cells should serve to address these questions and help understand the involvement of these gene products in human oncogenesis.

Acknowledgments

We thank P. Boukamp and N. Fusenig (German Cancer Research Center) for HaCaT cells, K. Moberg and J. Lees (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) for anti-E2F-4 antibodies, G. Peters (Imperial Cancer Research Fund) for p16 cDNAs, M. Dustin (Washington University) for confocal microscopy, T. Dixon for clerical help, and O. Kanagawa and the members of the Dowdy lab for critical input. D.A.G. was supported by an ASTRO fellowship. M.C.W. was supported by a National Institutes of Health Medical Scientist Training Program Training Grant (5 T32 GM07200). S.F.D. is an Assistant Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

ABBREVIATIONS

- pRb

retinoblastoma protein

- TGF-β

transforming growth factor β

- GST

glutathione S-transferase

- FACS

fluorescence-activated cell sorter

- MEM

minimal essential medium

References

- 1.Pardee A B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1974;71:1286–1290. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.4.1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weinberg R A. Cell. 1995;81:323–330. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90385-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sherr C J. Science. 1996;274:1672–1677. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sherr C J, Roberts J M. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1149–1163. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.10.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bagchi S, Weinmann R, Raychaudhuri P. Cell. 1991;65:1063–1072. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90558-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chellappan S P, Hiebert S, Mudryj M, Horowitz J M, Nevins J R. Cell. 1991;65:1053–1061. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90557-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Helin K, Lees J A, Vidal M, Dyson N, Harlow E, Fattaey A. Cell. 1992;70:337–350. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90107-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaelin W, Jr, Krek W, Sellers W R, DeCaprio J A, Ajchenbaum F, Fuchs C S, Chittenden T, Li Y, Farnham P J, Blanar M A, Livingston D M, Flemington E K. Cell. 1992;70:351–364. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90108-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lees E M, Harlow E. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:1194–1201. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.2.1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weintraub S J, Prater C A, Dean D C. Nature (London) 1992;358:259–261. doi: 10.1038/358259a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.La Thangue N B. Trends Biochem Sci. 1994;19:108–114. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(94)90202-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hall M, Peters G. Adv Cancer Res. 1996;68:67–108. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(08)60352-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeCaprio J A, Ludlow J W, Lynch D, Furukawa Y, Griffin J, Piwnica- Worms H, Huang C M, Livingston D M. Cell. 1989;58:1085–1095. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90507-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dowdy S F, VanDyk G H, Schreiber . In: Human Genome Methods. Adolph K, editor. Boca Raton, FL: CRC; 1997. , in press. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Won K A, Xiong Y, Beach D, Gilman M Z. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:9910–9914. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.20.9910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ajchenbaum F, Ando K, DeCaprio J A, Griffin J D. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:4113–4119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dunaief J L, Strober B E, Guha S, Khavari P A, Alin K, Luban J, Begemann M, Crabtree G R, Goff S P. Cell. 1994;79:119–130. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90405-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meyerson M, Harlow E. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:2077–2086. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.3.2077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nagahara H, Latek R R, Ezhevsky S A, Dowdy S F. In: Methods in Molecular Biology: 2-D Protein Gel Electrophoresis Protocols. Link A J, editor. Clifton, NJ: Humana; 1997. , in press. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parry D, Peters G. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:3844–3852. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.7.3844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moberg K, Starz M A, Lees J A. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:1436–1449. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.4.1436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mittnacht S, Lees J A, Desai D, Harlow E, Morgan D O, Weinberg R A. EMBO J. 1994;13:118–127. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06241.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hannon G J, Beach D. Nature (London) 1994;371:257–261. doi: 10.1038/371257a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reynisdottir I, Polyak K, Iavarone A, Massague J. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1831–1845. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.15.1831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matsushime H, Quelle D E, Shurtleff S A, Shibuya M, Sherr C J, Kato J Y. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:2066–2076. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.3.2066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee W H, Shew J Y, Hong F D, Sery T W, Donoso L A, Young L J, Bookstein R, Lee E Y. Nature (London) 1987;329:642–645. doi: 10.1038/329642a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Polyak K. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1242:185–199. doi: 10.1016/0304-419x(95)00009-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hall M, Bates S, Peters G. Oncogene. 1995;11:1581–1588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Green M, Loewenstein P M. Cell. 1988;55:1179–1188. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90262-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Frankel A D, Pabo C O. Cell. 1988;55:1189–1193. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90263-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fawell S, Seery J, Daikh Y, Moore C, Chen L L, Pepinsky B, Barsoum J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:664–668. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.2.664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koh J, Enders G H, Dynlacht B D, Harlow E. Nature (London) 1995;375:506–510. doi: 10.1038/375506a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lukas J, Parry D, Aagaard L, Mann D J, Bartkova J, Strauss M, Peters G, Bartek J. Nature (London) 1995;375:503–506. doi: 10.1038/375503a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Medema R H, Herrera R E, Lam F, Weinberg R A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:6289–6293. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.14.6289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mittnacht S, Weinberg R A. Cell. 1991;65:381–393. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90456-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dowdy S F, Hinds P W, Louie K, Reed S I, Arnold A, Weinberg R A. Cell. 1993;73:499–511. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90137-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hatakeyama M, Brill J A, Fink G R, Weinberg R A. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1759–1771. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.15.1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zwijsen R M, Wientjens E, Klompmaker R, van der Sman J, Bernards R, Michalides R J. Cell. 1997;88:405–415. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81879-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]