Abstract

Clostridium botulinum, an important pathogen of humans and animals, produces botulinum neurotoxin (BoNT), the most poisonous toxin known. We have determined by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) and Southern hybridizations that the genes encoding BoNTs in strains Loch Maree (subtype A3) and 657Ba (type B and subtype A4) are located on large (~280 kb) plasmids. This is the first demonstration of plasmid-borne neurotoxin genes in Clostridium botulinum serotypes A and B. The finding of BoNT type A and B genes on extrachromosomal elements has important implications for the evolution of neurotoxigenicity in clostridia including the origin, expression, and lateral transfer of botulinum neurotoxin genes.

Keywords: Clostridium botulinum, botulinum neurotoxin (BoNT), pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE), Southern hybridization

Introduction

Clostridium botulinum, is the causative agent of the debilitating disease botulism that affects humans and animals, due to its production of botulinum neurotoxin (BoNT). In addition to its importance as a pathogen, BoNTs are now widely used as pharmaceuticals to treat a myriad of hyperactive muscle disorders. In 2001, C. botulinum was listed as a category A select agent due to its potential use as a bioterrorism agent [1]. Seven distinguishable serotypes of BoNT, designated A-G, are produced by C. botulinum. BoNTs are produced as progenitor toxin complexes in which the neurotoxin is associated with nontoxic components: nonhemagglutinin (NTNH), hemagglutinin (HA) proteins, RNA, and other uncharacterized protein components [2]. The genes encoding the neurotoxin and associated protein components of the toxin complexes are organized in a cluster, and their location and composition varies among the different serotypes and strains [3]. The neurotoxin gene clusters for C. botulinum serotypes A, B, E and F are believed to be located on the chromosome, while the BoNT/C1 and BoNT/D clusters are carried on bacteriophages [4]. In C. botulinum serotype G the neurotoxin gene, cntA/G, was shown to reside on a large plasmid of ca. 114 kb [5].

Four BoNT/A subtypes (A1-A4) have recently been identified [6, 7, 8]. Although BoNT/A subtypes exhibit a high degree of sequence conservation, variations in substrate recognition and receptor binding regions are sufficient to significantly affect efficient vaccine and countermeasure development [6, 8]. It has also been observed that different type A strains even within the same subtype produce varying quantities of BoNT [9]. Experiments performed in our laboratory have determined that C. botulinum subtype A3 strain Loch Maree, and subtype A4 strain 657Ba, produce considerably less BoNT than most A1 and A2 subtype strains. This complicates purification of sufficient quantities of these proteins required for detailed studies. Interestingly, the dual neurotoxin strain 657Ba produces primarily BoNT/B and even lower quantities of BoNT/A than the Loch Maree strain.

To gain more insight into the differential expression of BoNT/A subtypes, with focus on strains A3 (Loch Maree) and A4 (657Ba), we performed comparative analyses of representative BoNT/A subtype strains by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) and Southern hybridizations with probes specific for the BoNT/A and B genes, cntA/A and cntA/B. Due to the limited and inconsistent production of neurotoxin in strains Loch Maree and 657Ba, we also investigated the potential involvement of bacteriophages and extrachromosomal elements in BoNT expression. Unexpectedly, we have found that, in contrast to subtypes A1 and A2, the genes encoding subtype neurotoxins BoNT/A3 in the A3 strain, and BoNT/A4 and BoNT/B in the A4 strain are on plasmids. This is the first demonstration of plasmid-located gene for BoNT in C. botulinum type A strains.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains

The following Clostridium botulinum type A subtype strains from our laboratory culture collection were used in this study: ATCC 3502 (subtype A1), 62A (A1), KyotoF (A2), 5328A (A1/A2), Loch Maree (A3), 657Ba (A4) and NCTC 2916 (A(B)). All cultures were maintained as frozen stocks at −80°C in TPGY (50g/liter trypticase peptone, 5g/liter Bacto peptone, 4g/liter D-glucose, 20g/liter yeast extract, 1g/liter cysteine-HCl, pH 7.4) broth supplemented with 40% glycerol. All bacterial media components and chemicals were purchased from Becton Dickinson Microbiology Systems, Sparks, MD and Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO.

Preparation of agarose plugs for PFGE analysis

Bacterial cultures were grown anaerobically, PFGE plugs prepared, and PFGE performed as previously described [10].

Southern Hybridization

Type A neurotoxin gene sequences of all four C. botulinum type A subtype strains [6] were aligned and primers were designed to anneal to a conserved region of the C-terminal trefoil subdomain in the binding domain of the heavy chain. The forward primer: 5′GCTACTAATGCATCACAGGCAGGCG3′ and reverse primer: CCCATGAGCAACCCAAAGTCC3′ were used in PCR amplification to generate a 268 bp DNA probe for cntA/A. A portion of the light chain of cntA/B was PCR amplified from the genomic DNA of C. botulinum strain 657Ba to generate a fragment of 592 bp using: forward primer: 5′TTTGCATCAAGGGAAGGCTTCG3′ and reverse primer: 5′AGGAATCACTAAAATAAGAA3′. A 16S rDNA probe for C. botulinum type A was amplified by PCR using genomic DNA from an A1 subtype strain as a template to yield a DNA fragment of 1020 bp using primers: forward primer: 5′GCGGCGTGCCTAACACATGC3′ and reverse primer: 5′ATCTCACGACACGAGCTGAC3′.

The PCR products were purified from agarose gels using Qiagen extraction kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), and were radioactively labeled with 32P using the Megaprime DNA labeling system (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences, Piscataway, NJ). The DNA samples separated by PFGE were transferred to a positively charged nylon membrane (Immobilon-NY+, Millipore, Bedford, MA) overnight by downward capillary transfer in 0.4 M NaOH, 1.5 M NaCl. The membranes were neutralized in 2 M Tris-HCl, pH 7.0 for 10 minutes, rinsed with 2X SSC and fixed at 80°C for 30 minutes under vacuum. Hybridization was performed at 42°C for 16 hours in a solution containing 5X Denhardt, 6X SSC, 50% formamide, 1% SDS, 100 μg/ml herring sperm DNA (Promega, Madison, WI) and 32P-labeled probes. All hybridization solutions and buffers were prepared according to standard protocols [11]. After hybridizations the membranes were washed twice for 5 minutes each at room temperature with 2X SSC, 0.1% SDS and twice for 15 minutes each at 42°C. The membranes hybridized with the ribosomal probe were washed twice for 2 hours each at 65°C with 0.1X SSC, 0.1% SDS. Autoradiography of the membranes was performed for 16 to 48 hours at −70°C using Kodak BioMax MS film with a BioMax intensifying screen (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY).

Bacteriophage induction

Bacterial cultures of C. botulinum strains Loch Maree (subtype A3) and 657Ba (subtype A4) were grown anaerobically at 37oC in 10 ml tubes of TPGY media to an OD600 of 0.2. Mitomycin C at a final concentration of 5μg/ml was added to the cultures to induce cell lysis. The cultures were further incubated at 37°C for 4–6 hours or until lysis was complete. The OD600 of the cultures was measured at 1 hour intervals. When lysis was complete the cultures were cooled to room temperature and bacteriophage particles were isolated following a standard protocol [11]. Bacteriophage particles were embedded in agarose plugs, treated as described previously [10], and subjected to PFGE analysis and Southern hybridization.

Results and Discussion

C. botulinum strains Loch Maree and 657Ba produce very low quantities of BoNT/A3 and BoNT/A4, respectively, compared to other BoNT/A strains (unpublished data). Therefore, purification of sufficient quantities of these neurotoxins required for development of therapeutics and countermeasures is obstructed. The overall goal of this study was to evaluate the genetic location of the neurotoxin genes in these strains, which could impact the levels of BoNTs.

Previous studies in our and other laboratories have observed significant variations in growth patterns and BoNT production levels among different C. botulinum serotypes and even between strains within the same serotype [9]. Kinetic studies of C. botulinum type A1 and A2 strains showed a temporal regulation of BoNT production that onsets during late log and early stationary phase [9]. Neurotoxin production differed between the strains and was found to be primarily dependent on nutritional factors, cell lysis, and sporulation [3, 9]. It was established that in typical A1 and A2 subtype strains, neurotoxin expression and the formation of the progenitor toxin complex increased upon prolonged incubation reaching maximum quantities at 96 hours. C. botulinum strains Loch Maree and 657Ba showed no increase in the levels of neurotoxin produced after 24 hours, and consistent quantities were rarely detected between different batch cultures (data not shown).

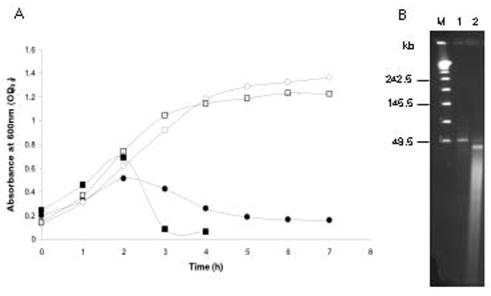

The neurotoxin gene clusters in C. botulinum serotypes C and D are carried by bacteriophages [4]. The bacteriophage carrier state in these serotypes has been termed pseudolysogeny because of the unstable nature of the prophage-bacterium relationship in which the prophage is often lost resulting in a nontoxigenic state [4]. We suspected that a similar pseudolysogenic state may be responsible for the inconsistent production of BoNTs in strains Loch Maree and 657Ba. To test this hypothesis, bacterial cultures were treated with mitomycin C and bacteriophage particles were isolated from the culture lysates. Upon induction strain Loch Maree displayed a typical lysis pattern achieving complete lysis after six hours (Fig. 1A). C. botulinum strain 657Ba displayed a much faster lysis which was complete after only three hours (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

Induction of bacteriophages in C. botulinum strains Loch Maree and 657Ba and PFGE analysis of phage DNA. (A) Lysis curve of strains Loch Maree and 657Ba after induction with mitomycin C (5μg/ml) added at an OD600 of 0.2. (B) PFGE analysis of bacteriophage DNA isolated from strains Loch Maree (lane 1) and 657Ba (lane 2). Lambda Ladder PFG Marker (New England Biolabs) (Lane M). PFGE conditions: pulse time 1–20 seconds, 6V/cm, at 14°C for 16 h. Loch Maree (circle), 657Ba (square) grown in TPGY without mitomycin C (open) and with mitomycin C (closed).

PFGE analysis revealed a DNA band of 48.5 kb in the bacteriophage DNA preparations from both strains (Fig. 1B). A second DNA band of approximately 24 kb was also visible in the bacteriophage DNA preparation from strain 657Ba. Significant degradation of the bacteriophage DNA preparation from strain 657Ba seen in Fig. 1B was most likely due to the presence of high levels of endogenous proteinases and DNases released during rapid lysis of this particular strain upon bacteriophage induction. To test whether these bacteriophages harbor the neurotoxin gene, Southern hybridization with a cntA/A probe was conducted. No hybridization signals were observed with the bacteriophage DNAs (data not shown), indicating that the bacteriophage particles isolated from these strains do not carry the type A neurotoxin gene. The bacteriophages isolated from strains Loch Maree and 657Ba upon mitomycin C induction may contribute indirectly to the regulation, synthesis and release of neurotoxin.

The neurotoxins among the four BoNT/A subtypes show 84 to 93% identity [6]. The organization and composition of genes within the neurotoxin gene clusters also differ among the subtypes [3]. Presently, the nucleotide sequence of the entire genome has been determined for only one C. botulinum strain, ATCC 3502 [12], therefore the extent of sequence variation at the genome level between different subtype strains is not known. To compare the genomes of representative C. botulinum strains producing BoNT/A1-A4 neurotoxins, PFGE and Southern hybridization analyses with neurotoxin gene specific probes were performed.

In clostridia, preparation of high quality DNA plugs for PFGE analysis is challenging and some strains cannot be readily typed because they contain very high levels of endogenous DNases [3, 10]. To minimize the nucleolytic degradation of DNA samples bacterial cultures were fixed with formaldehyde [10]. Typically, PFGE is performed with DNA samples that have been digested with rare cutting restriction endonucleases (RE), but in order to verify the quality of the DNA prior to restriction analysis, nondigested samples were first analyzed.

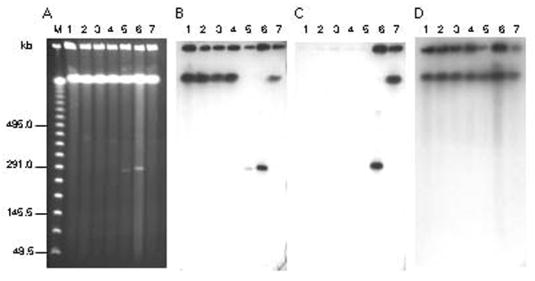

We observed that a significant portion of DNA remained in the wells of the gel, representing intact chromosomal DNA. However, a portion of chromosomal DNA migrated a short distance into the gel, most likely corresponding to sheared DNA due to DNase activity (Fig. 2). Interestingly, several faint DNA bands that migrated beneath the sheared chromosomal DNA in strains 62A, 5328A, Loch Maree, and 657Ba were also observed (Fig. 2A), suggesting the presence of large extrachromosomal DNA elements. The extrachromosomal DNA molecules in strains Loch Maree and 657Ba migrated at a similar size at approximately 280 kb, while the DNA band in strain 657Ba was slightly larger (Fig. 2A). This band also appeared to be present at a higher copy number due to the increased intensity of the band observed in the ethidium bromide stained gel, as well as by stronger hybridization signals in the Southern blot (Figs. 2A, B).

Figure 2.

PFGE and Southern hybridization analyses of C. botulinum type A subtypes. (A) PFGE of non-digested DNA of C. botulinum A subtypes. Southern hybridizations were performed with cntA/A probe (B), cntA/B probe (C), and 16S rRNA gene probe (D). Lanes: lambda ladder PFG markers (New England Biolabs) (Lane M), ATCC 3502 (Lane 1), 62A (Lane 2), Kyoto F (Lane 3), 5328A (Lane 4), Loch Maree (Lane 5), 657Ba (Lane 6), NCTC 2916 (Lane 7). PFGE conditions: pulse time 5–60 seconds, 6V/cm, at 14°C for 27 h.

It has been determined that supercoiled plasmids migrate independently of the pulse time in PFGE, but large circular DNA molecules that are nicked or enzymatically relaxed fail to enter the gel matrix [13]. To verify the nature of these extrachromosomal elements, PFGE of nondigested DNA of these strains was performed several times employing different pulse times (data not shown). However, these extrachromosomal DNA molecules consistently migrated through the gels at the same size relative to the marker bands, suggesting that these bands may correspond to linear DNA plasmids.

Cryptic plasmids ranging in size from 3 kb to 125 kb have been isolated from all C. botulinum serotypes but is strain dependent [14]. C. botulinum type G is the only serotype to date known to harbor a large plasmid (114 kb), which contains the BoNT/G gene cluster [5]. Clostridium tetani also carries a large plasmid (74 kb) possessing the tetanus neurotoxin (TeNT) gene [15]. It has been assumed that the neurotoxin gene clusters in C. botulinum serotypes A, B, E and F are located on the chromosomes. This has been confirmed for C. botulinum serotype A (subtype A1) through sequencing of the genome of the strain ATCC 3502 [12]. Prior to the present study, plasmids larger than that occurring in C. botulinum type G have not been identified in neurotoxigenic clostridia. The solventogenic Clostridium acetobuytlicum contains a megaplasmid (210 kb) which carries solventogenic genes encoding proteins involved in the production of acetone and butanol [16].

The finding of large extrachromosomal elements in C. botulinum type A strains 62A, 5328A, Loch Maree and 657Ba, prompted us to investigate in more detail their potential role in neurotoxin production. Southern hybridizations were performed using probes specific for cntA/A, and cntA/B first using nondigested DNA samples (Figures 2B and C). Southern hybridization of the PFGE of nondigested DNA with the cntA/A probe produced strong signals at the well position, containing genomic and circular DNA, as well as with the band of sheared chromosomal DNA in all strains except Loch Maree and 657Ba (Fig. 2B). In these strains the cntA/A probe hybridized to DNA at the well position, but not with the sheared chromosomal DNA (Fig. 2B). Surprisingly, hybridization of cntA/A probe with the DNA bands at ~280 kb were observed for Loch Maree and 657Ba strains, indicating that the toxin gene is located on these extrachromosomal DNA molecules (Fig. 2B). The extrachromosomal DNA bands in strains 62A and 5328A did not hybridize with the cntA/A probe.

C. botulinum NCTC 2916 is an A(B) strain that produces active BoNT/A and carries a silent, unexpressed type B toxin gene cluster that is likely located on the chromosome [17]. Hybridization of cntA/B with the DNA of NCTC 2916 revealed strong signals at the level of sheared chromosomal DNA and at the well position supporting the location of cntA/B on the chromosome in this strain (Fig. 2C). Unexpectedly, in strain 657Ba, the cntA/B probe hybridized with the ~280 kb DNA band as well as with DNA at the well position (Fig. 2C). The presence of both neurotoxin gene clusters on the same plasmid was intriguing, because the location of cntA/B in the dual neurotoxin strain, 657Ba, was previously assumed to be on the chromosome. These findings raise questions regarding the differential expression of various quantities of neurotoxin since BoNT/B is produced more than BoNT/A4 in culture.

To provide further evidence that the ~280 kb DNA elements in C. botulinum strains Loch Maree and 657Ba are plasmids and not sheared fragments of genomic DNA, we performed Southern hybridization of the nondigested DNA using a probe specific for 16S rDNA. Ribosomal DNA is specific to chromosomes and rarely found on plasmids [18]. Only sheared chromosomal DNA and DNA that remained at the well position hybridized with the 16S rDNA probe in all strains (Fig. 2D), no hybridization signals were observed with the extrachromosomal DNA bands. This supported that the DNA elements in these strains are plasmids.

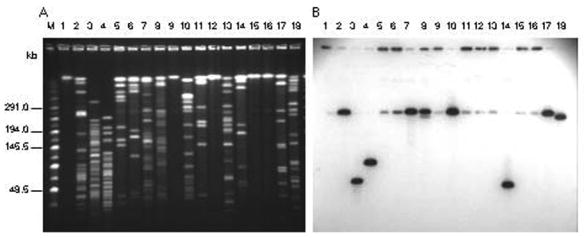

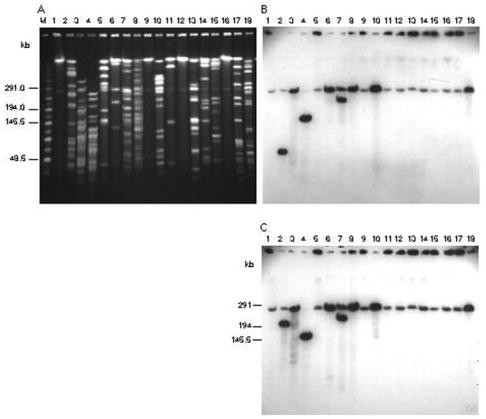

To confirm the presence of cntA/A and cntA/B genes on these extrachromosomal DNA molecules in strains Loch Maree and 657Ba, seventeen rare cutting RE were chosen for the restriction analysis and Southern hybridizations of DNA preparations from these strains (Figs. 3, 4). The majority of the RE chosen to digest the DNA of strains Loch Maree and 657Ba resulted in the same hybridization signals with uncut DNA, indicating that these enzymes did not cleave the plasmids (Figs. 3B, 4B, C). However, digests with five RE in both strains showed an increase in the intensity of the ~280 kb band in the ethidium bromide stained gels as well as produced stronger hybridization signals with the neurotoxin gene probes, while the hybridization signals at the well positions decreased (Figs. 3B, 4B and 4C). This suggests that the plasmids were linearized by these REs and thus were able to enter and migrate through the gels at ~280 kb. Four additional REs apparently cleaved the plasmid more than once in strain Loch Maree because hybridization signals were observed with DNA bands smaller than ~280 kb (Fig. 3). Similarly, three REs also cut the plasmid in strain 657Ba more than once (Fig. 4). Although the cntA/A and cntA/B genes are both present on the plasmid in 657Ba they were found to be located on different areas of the DNA element as observed by the Southern hybridizations of DNA digested with the RE AatII (Figs. 4B and 4C). Future studies are necessary to map the location and determine the distance between both neurotoxin gene clusters on the plasmid in strain 657Ba.

Figure 3.

PFGE and Southern hybridization analyses of digested DNA from C. botulinum strain Loch Maree. (A) PFGE of digested DNA of Loch Maree. (B) Southern hybridization of Loch Maree PFGE with the cntA/A probe. Lanes 1: Nondigested DNA, Digests with: 2-AatII, 3-ApaI, 4-BglI, 5-EagI, 6-MluI, 7-NaeI, 8-NarI, 9-NotI, 10-NruI, 11-PvuI, 12-RsrII, 13-SacII, 14-SalI, 15-SbfI, 16-SfiI, 17-SmaI, 18-XhoI; M- MidRange II PFG marker (New England Biolabs). PFGE conditions: pulse time 1–30 seconds, 6V/cm, at 14°C for 24 h.

Figure 4.

PFGE and Southern hybridization analyses of digested DNA from C. botulinum strain 657Ba. (A) PFGE of digested DNA of 657Ba. (B) Southern hybridization of 657Ba PFGE with the cntA/A probe. (C) Southern hybridization of 657Ba PFGE with the cntA/B probe. Lanes 1-Nondigested DNA, Digests with: 2-AatII, 3-ApaI, 4-BglI, 5-EagI, 6-MluI, 7-NaeI, 8-NarI, 9-NotI, 10-NruI, 11-PvuI, 12-RsrII, 13-SacII, 14-SalI, 15-SbfI, 16-SfiI, 17-SmaI, 18-XhoI; M- MidRange II PFG marker (New England Biolabs). PFGE conditions: pulse time 1–30 seconds, 6V/cm, at 14°C for 24 h.

Plasmids from several C. botulinum type A strains have been isolated, but none of the plasmids have been associated with neurotoxin production [19]. This is the first demonstration that cntA/A, and cntA/B genes are located on a large plasmid (~280kb) in type A neurotoxin producing C. botulinum strains. This finding has important implications for evolution and pathogenicity of C. botulinum, including acquisition and expression of the toxins, and lateral transfer of toxin genes to nonpathogenic bacteria. Further studies are required to characterize the plasmids in detail including: their isolation, identification of genes carried on the plasmids, the degree of their relatedness, and the mechanisms of differential expression of these neurotoxins.

Acknowledgments

This work was sponsored by the NIH/NIAID Regional Center of Excellence for Biodefense and Emerging Infectious Diseases Research (RCE) Programs. The authors wish to acknowledge membership within and support from the Pacific Southwest Regional Center of Excellence grant U54 AI065359 and the Great Lakes Regional Center of Excellence grant U54-AI057153. We would like to thank Barbara Cochrane for her expertise in the preparation of the figures.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Arnon AS, Schechter R, Inglesby TV, Henderson DA, Bartlett JG, Ascher MS, Eitzen E, Fine AD, Hauer J, Layton M, Lillibridge S, Osterholm MT, O’‘‘Toole T, Parker G, Perl TM, Russell PK, Swerdlow DL, Tonat K. Botulinum toxin as a biological weapon. JAMA. 2001;285:1059–1081. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.8.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schantz EJ, Johnson EA. Properties and use of botulinum toxin and other microbial neurotoxins in medicine. Microbiol Rev. 1992;56:80–99. doi: 10.1128/mr.56.1.80-99.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson EA, Bradshaw M. Clostridium botulinum and its neurotoxins: a metabolic and cellular perspective. Toxicon. 2001;39:1703–1722. doi: 10.1016/s0041-0101(01)00157-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson EA. Bacteriophages Encoding Botulinum and Diptheria Toxins. In: Waldor MK, Friedman DI, Adhya SL, editors. Phages: Their Role in Bacterial Pathogenesis and Biotechnology. ASM Press; Washington, D.C: 2005. pp. 280–296. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou Y, Sugiyama H, Nakano H, Johnson EA. The genes for the Clostridium botulinum type G toxin complex are on a plasmid. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2087–2091. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.5.2087-2091.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arndt JW, Jacobson MJ, Abola EE, Forsyth CM, Tepp WH, Marks JD, Johnson EA, Stevens RC. A structural perspective of the sequence variability within botulinum neurotoxin subtypes A1-A4. J Mol Biol. 2006;362:733–742. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.07.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hill KK, Smith TJ, Helma CH, Ticknor LO, Foley BT, Svensson RT, Brown JL, Johnson EA, Smith LA, Okinaka RT, Jackson PJ, Marks JD. Genetic diversity among botulinum neurotoxin-producing clostridial strains. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:818–237. doi: 10.1128/JB.01180-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith TJ, Lou J, Geren IN, Forsyth CM, Tsai R, LaPorte SL, Tepp WH, Bradshaw M, Johnson EA, Smith LA, Marks JD. Sequence variation within botulinum neurotoxin serotypes impacts antibody binding and neutralization. Infect Immun. 2005;73:5450–5457. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.9.5450-5457.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bradshaw M, Dineen SS, Maks ND, Johnson EA. Regulation of neurotoxin complex expression in Clostridium botulinum strains 62A, Hall A-hyper, and NCTC 2916. Anaerobe. 2004;10:321–333. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson EA, Tepp WH, Bradshaw M, Gilbert RJ, Cook PE, McIntosh EDG. Characterization of Clostridium botulinum strains associated with an infant botulism case in the United Kingdom. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:2602–2607. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.6.2602-2607.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sambrook J, Russell DW. Molecular Cloning-A Laboratory Manual. 3. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sebaihia M, Peck MW, Minton NP, Thomson NR, Holden MTG, Mitchell WJ, Carter AT, Bentley SD, Mason DR, Crossman L, Paul CJ, Ivens A, Wells-Bennik MHJ, Davis IJ, Cerdeno-Tarraga AM, Churcher C, Quail MA, Chillingworth T, Feltwell T, Fraser A, Goodhead I, Hance Z, Jagels K, Larke N, Daddison M, Moule S, Mungall K, Norbertczak H, Rabbinowitsch E, Sanders M, Simmonds M, White B, Whithead S, Parkhill J. Genome sequence of a proteolytic (group I) Clostridium botulinum strain Hall A and comparative analysis of the clostridial genomes. Genome Res. 2007:1–11. doi: 10.1101/gr.6282807. epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beverly SM. Characterization of the ‘‘‘unusual’‘‘ mobility of large circular DNAs in pulsed field-gradient electrophoresis. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:925–939. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.3.925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strom MS, Eklund MW, Poysky FT. Plasmids in Clostridium botulinum and related clostridium species. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1984;48:956–963. doi: 10.1128/aem.48.5.956-963.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Finn CW, Silver RP, Habig WH, Hardegree MC, Zon G, Garon CF. The structural gene for tetanus neurotoxin is on a plasmid. Science. 1984;224:881–884. doi: 10.1126/science.6326263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cornillot E, Nair RV, Papoutsakis ET, Soucaille P. The genes for butanol and acetone formation in Clostridium acetobutylicum ATCC 824 reside on a large plasmid whose loss leads to degeneration of the strain. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5442–5447. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.17.5442-5447.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodriguez JM, Collins MD, East AK. Gene organization and sequence determination of the two botulinum neurotoxin gene clusters in Clostridium botulinum type A(B) strain NCTC 2916. Curr Microbiol. 1998;36:226–231. doi: 10.1007/s002849900299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ochman H. Bacterial evolution: chromosome arithmetic and geometry. Curr Biol. 2002;12:R427–R428. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00916-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weickert MJ, Chambliss GH, Sugiyama H. Production of toxin by Clostridium botulinum type A strains cured of plasmids. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1986;51:52–56. doi: 10.1128/aem.51.1.52-56.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]