Abstract

The toxicity of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) has been attributed widely to receptor-mediated effects, buttressed by the popularity of the Toxic Equivalency Factor. We propose that a crucial toxic mechanism of lower-chlorinated PCBs is their enzymatic biotransformation to electrophiles, including quinoid metabolites, that bind intracellular sulfhydryl groups, such as those found in microtubulin and enzymes like telomerase. To test this hypothesis, we have examined micronuclei induction, cell cycle, and telomere shortening in cells in culture. Our findings show a large increase in micronuclei frequency and cell cycle perturbation in V79 cells, and a marked decrease in telomere length in HaCaT cells exposed to 2-(4′-chlorophenyl)-1,4-benzoquinone (PCB3pQ).

Keywords: PCB, micronucleus, DNA, telomere shortening, sulfhydryl binding

1. Introduction

Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) are ubiquitous, persistent, lipophilic environmental pollutants that were widely used for numerous industrial applications (ATSDR, 2000). Human exposure to PCBs occurs through both diet and inhalation (ATSDR, 2000; Ludewig et al., 2007). The physiological effects of PCB exposure are well-documented in epidemiological, in vivo, and in vitro studies (Robertson and Hansen, 2001).

The focus of this paper is on the ability of 2-(4′-chlorophenyl)-1,4-benzoquinone (PCB3pQ) to increase the frequency of micronuclei and shorten telomeres. These two effects may be mechanistically connected by the well-known affinity of quinone metabolites for intracellular sulfhydryls, such as those found in microtubulin and many enzyme proteins. Thiol binding by PCB quinone metabolites has been established for glutathione, the thiol found in highest concentration in the cell, and topoisomerase II, an enzyme involved in DNA replication (Amaro et al., 1996; Bender et al., 2007; Srinivasan et al., 2002). Quinoid protein adducts have also been found in vivo after the administration of PCB 52 (Lin et al., 2000). We propose that metabolic activation of lower-chlorinated PCBs to electrophilic quinoid products that bind sulfhydryl groups is an important mechanism possibly manifesting as chromosome damage, measured in the current study as both micronuclei induction and shortened telomeres.

Micronuclei, examined via fluorescence microscopy, appear as self-contained fragments, and result from either chromosome breaking (clastogenic) or chromosome loss (aneugenic) processes (Fenech, 2000; Fenech, 2006; Kirsch-Volders et al., 2002). Clastogenic events encompass a variety of mechanisms, leading to chromosome tearing during cell division. Whole chromosome loss can result from inhibition of proper tubulin function, such that the spindle fails to fuse with the kinetochore of the chromosome. This error results in the loss of the chromosome from the nucleus during cell division (Fenech, 2006). By employing an immunostain to kinetochore proteins, the micronuclei can be attributed to either a clastogenic or aneugenic event, yielding insights into the toxic mechanism. In vitro micronucleus studies with specific PCB congeners have to date only been published for PCB 77 (Belpaeme et al., 1996). Here negative results for induction of micronuclei were obtained in human lymphocytes exposed to PCB 77. However, this study did not include the use of PCB metabolites. Several in vivo and in vitro micronuclei studies examining rodent cells after exposure to PCB mixtures reported negative findings, whereas exposure of fish in vivo gave positive results. A comprehensive overview of these results has previously been presented (Ludewig, 2001).

Telomeres are highly conserved structures that consist of repetitive oligomers found at the end of chromosomes in all eukaryotes. In humans, these structures extend a few thousand base pairs before terminating as single strand that forms higher-order G-quadruplex structures (de Lange et al., 2006). Their main role is to protect the chromosomes, whose “sticky ends” would otherwise fuse together, resulting in irreversible damage to the cell's genetic material. Telomeres also guard against cellular recognition of the ends of a chromosome as double-stranded DNA breaks. In addition, many protein interactions occur on the telomeres, adding another layer of complexity and protection to the genome. Telomerase, the enzyme responsible for maintenance of telomere length as cells divide, is a highly sensitive reverse transcriptase shown previously to be selectively inhibited by electrophilic species (Huang et al., 2005). While it was initially thought that telomere length acted simply as a shrinking marker toward senescence and apoptosis, telomere biology has proven to be much more complex (de Lange et al., 2006).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

PCB3pQ was synthesized as described (Amaro et al., 1996). All cell culture media and components, i.e. Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM) with 2 mM L-glutamine, fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin-streptomycin (P/S) solution, phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and sodium pyruvate were from GIBCO (Grant Island, NY, USA). Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and sulforhodamine B were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). Genistein (5,7,4′ Trihydroxyisoflavone [446-72-0] 99+%) was purchased from Indofine Chemical Company, Inc. (Hillsborough, NJ). All other reagents were obtained from Fischer Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA), if not specified otherwise.

2.2. Micronucleus Assay with Cytotoxicity and Cell Cycle Analysis

The V79 (Chinese Hamster lung fibroblast) cell line was purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA, USA). V79 cells were cultured according to recommended conditions in DMEM with 10% FBS, sodium pyruvate, and penicillin/streptomycin. The cells were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 and passaged regularly before reaching confluency. For the experiments a fresh stock solution of PCB3pQ was prepared from neat compound in 100% DMSO immediately before use and added to the medium. The final concentration of DMSO in cell culture medium was 1% (this level of DMSO was previously shown to have no influence on cell growth/toxicity and MN induction in V79 cells). Genistein, the positive control in the micronucleus assay, was dissolved in 100% DMSO and cells were exposed to a concentration of 10 μM. Genistein was chosen as positive control, since it is, like PCB3pQ, a topoisomerase II inhibitor. Cytotoxicity and micronucleus experiments were carried out in parallel with common exposure medium and cell suspension. The cell cycle experiment was performed separately.

For cytotoxicity determination of PCB3pQ, ten thousand V79 cells were seeded per well in 24 well plates. Six hours later the medium was removed and fresh medium with different concentrations of PCB3pQ or solvent alone was added. After exposure for 6 h the medium was changed with fresh medium without compounds. Immediately before and after exposure and after a post-exposure period of 14 and 22 h cells from each treatment group were fixed with a 10% trichloroacetic acid solution for 30 minutes at 4°C. Cells were then washed with nanopure water, allowed to dry and stained with Sulforhodamine B (SRB) in 1% acetic acid. A solution containing only 1% acetic acid was used to wash unbound dye from plates. Bound dye was solubilized in 10 mM Tris base by shaking for ten minutes. Fluorescence was measured using a Tecan Fluor Genios Pro Plate Reader (Mannedorf/Zürich, Switzerland) at 540 nm excitation and 585 nm emission wavelength. All exposures were done in triplicates. Statistical significance was calculated by t-test analysis.

Four thousand cells were seeded in each chamber of Nunc Lab-Tek 8 well chamber slides (Rochester, NY) for microscopic examination. One slide was prepared for each different concentration of test compound, positive control, and solvent control for each time point tested. Immunohistochemical analysis was performed with the following antibodies: (tubulin analysis) anti-alpha tubulin monoclonal, from mouse, and TRITC-conjugated anti-mouse immunoglobulin G supplied by Sigma; (centromere analysis, i.e. CREST status) purified human anti-centromere proteins in 0.1% sodium azide from Antibodies, Inc. (Davis, CA, USA) and anti-human polyvalent immunoglobulins from Sigma. An antifade solution containing 0.1 mg/mL p-phenylenediamine in PBS was used, which also contained 0.1 ug/mL DAPI for nuclei staining. Antibodies were used in a 1% BSA solution and slides were blocked with goat serum. Micronuclei and immunohistochemistry were evaluated on an Axio Imager A1 microscope from Zeiss AG (Goettingen, Germany) using 40x and 63x objectives. The experiment was performed twice and scored by 2 independent individuals. Each time at least 1,000 cells were scored per data point. Nucleic material that was distinctly separate from the main nucleus and had comparable staining intensity as the nucleus was scored as micronucleus and examined for CREST status. Images were captured with an AxioCam monochrome CCD using AxioVision software.

For cell cycle analysis cells were collected after 3h and 6h of exposure and 6 and 14 h post-exposure time by trypsinization. Pellets of approximately 500,000 cells were fixed with ethanol, treated with RNase, and stained following the protocol contained in the CyStain PI Absolute kit from Partec (Munster, Germany). Cell cycle analysis was performed on a Becton Dickinson FACS Calibur with excitation at 488 nm by an argon ion laser. Determination of cell cycle compartments was accomplished using ModFit 3.0 software (Verity Software House, Topsham, ME).

2.3. Telomere Length Assay and Proliferation during long term exposure

The human keratinocyte (HaCaT) cell line was obtained from Dr C. Svensson, University of Iowa. HaCaT cells were maintained as recommended in DMEM with 10% FBS and penicillin/streptomycin and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2. For the 11-week exposure of the telomere length assay cells were kept in medium with 1, 2,5, or 5 μM PCB3pQ or solvent alone and passaged weekly at 100,000 cells per 10 cm plate with one medium change on day 4 of each week. Cells were counted using a Neubauer hemecytometer on every 7th day after trypsinization (0.25% trypsin with EDTA) to determine the proliferation rate. A fresh stock solution of 20 mM PCB3pQ was prepared from neat compound in 100% DMSO each time the exposure medium was renewed (at 4 days and again at 7 days). The final concentration of DMSO in media was 0.05%.

After 11 weeks of exposure cells were collected by trypsinization and centrifuged at 290g for five minutes. DNA was isolated from cell pellets using the Qiagen (Hilden, Germany) DNA Blood Mini Kit following manufacturer's protocol. qPCR reactions and calculations were performed on an Eppendorf realplex2 thermal cycler in 96 well optical plates following a protocol based on Cawthon method (Cawthon, 2002). Briefly, 12 ng of DNA was amplified in well-matched separate telomere and single gene plates followed by a ΔΔCt calculation which compares the telomere signal to the single gene signal for each replicate. Measurements were performed in quadruplicate. SYBR green was excited at ∼470 nm by a dedicated light emitting diode in each well, with fluorescence intensity measurements occurring at 520 nm. All PCR reagents were of molecular biology grade. Statistical analysis was performed with ANOVA using SAS 9.0 (Cary, NC).

3. Results

3.1 Cytotoxicity, Micronuclei Induction, Cell Cycle Effects and Tubulin Disturbance after PCB3pQ-exposure of V79 cells

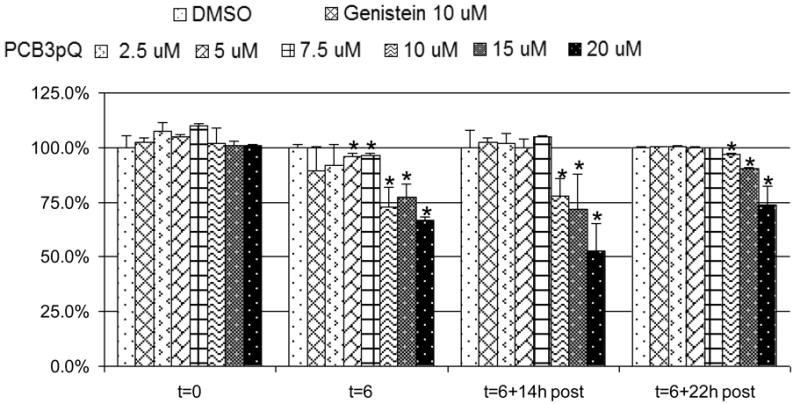

Cytotoxicity/growth inhibition of PCB3pQ to V79 was determined and is presented in Figure 1. Twenty μM of PCB3pQ induced approximately 50% reduction of cells after 6 h of treatment with 14 h post-exposure recovery. Ten and 15 μM concentrations of PCB3pQ reduced the cell number by about a quarter immediately after 6 h exposure and after an additional 14 h of recovery. Concentrations of PCB3pQ that exhibited greater than 20% decrease of cells (20 μM, 15 μM, and 10 μM) were excluded from MN analysis to avoid false-positive results due to general toxicity. As shown in Figure 1, concentrations at or below 7.5 μM were well tolerated, and therefore included in micronucleus analysis.

Figure 1. Cytotoxicity of PCB3pQ as measured by SRB.

Cells were seeded six hours prior to exposure. Exposure began at t= 0 hours and continued for 6 h (t= 6 h), followed by up to 22 h post-exposure period without compounds. Values are presented as percent of DMSO-control. Data represent one experiment. * denotes statistically different from DMSO value as evaluated by student's t-test.

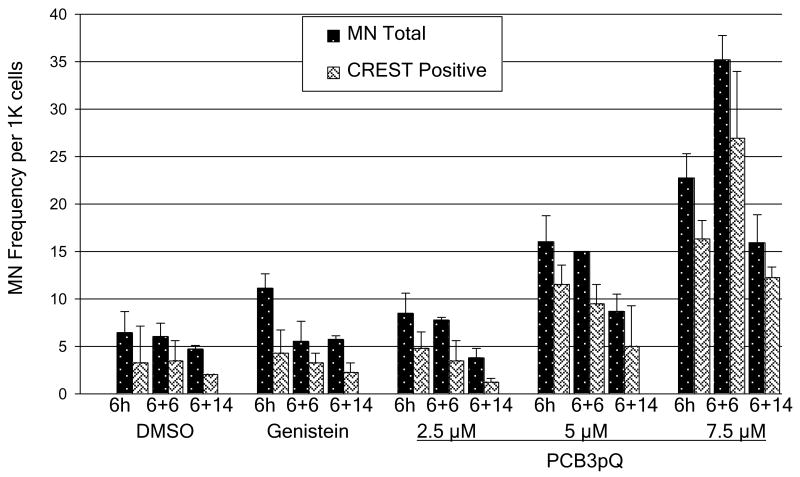

As shown in Fig. 2, the spontaneous number of total micronuclei in our V79 cells was about 5/1000 cells, of which 10-50% stained CREST-positive. Our positive control genistein, a topoisomerase II poison and known inducer of CREST-negative MN in V79 cells (Bandele and Osheroff, 2007; Kulling and Metzler, 1997), roughly doubled the number of micronuclei when compared to solvent control after the six hour exposure, primarily due to chromosome breaks (CREST-negative MN), but this effect was greatly lessened after 6 or 14 h post-exposure. PCB3pQ was tested at 3 different concentrations, 2.5, 5.0, and 7.5 μM. A six hour exposure to these low micromolar concentrations of PCB3pQ resulted in a 2 to 5-fold, dose-dependent increase in micronuclei formation. With the highest concentration of PCB3pQ this effect further increased during the six hours post exposure period to nearly 34 MN/1000, but slowly subsided afterwards. With the 2 lower concentrations of PCB3pQ this decline in MN frequency was already visible 6 h post-exposure. Unlike genistein, PCB3pQ induced MN were nearly exclusively CREST-positive.

Figure 2. Induction of micronuclei by PCB3pQ after 6 h of exposure and 6 and 14 h post-exposure.

Genistein poisons topoisomerase II and causes roughly a doubling of micronuclei frequency of mostly CREST negative micronuclei. PCB3pQ increases micronuclei frequency from 2-6 fold, with 5 μM and 7.5 μM causing a majority of CREST positive micronuclei. Data represent the mean, calculated from two independent experiments. Bars indicate standard error.

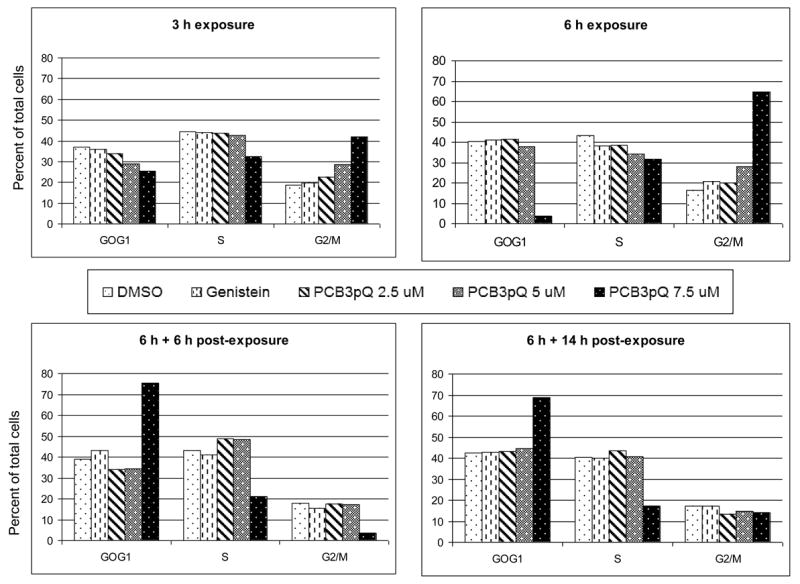

This very strong increase in micronuclei frequency after treatment with 7.5 μM PCB3pQ was also accompanied by an increasing cell cycle arrest in G2/M during the exposure, as shown in Fig. 3. Six hours following the removal of the compound cells had progressed into the G0/G1 phase which was still increased, although to a lower degree, after 14 hours of recovery. The 5 μM concentration of PCB3-pQ induced a smaller cell cycle block in G2/M during exposure, resulting in roughly a doubling of the cells in this cell cycle phase after 6 h of exposure. Genistein exposure at 10 μM had no significant effect on cell cycle progression.

Figure 3. PCB3pQ arrests cells in G2/M after 6 h exposure.

The effect is most dramatic at 7.5 μM, with the majority of the cell population arrested in G2/M during the exposure period (6 h), but starting to progress through the cell cycle after PCB3pQ is removed from the medium.

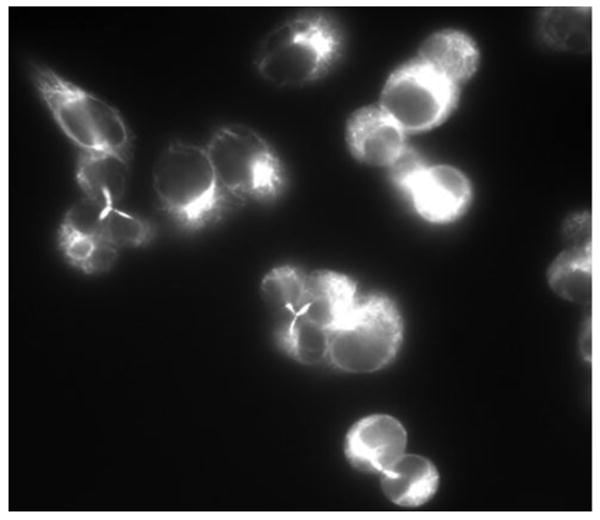

Immunostaining of tubulin yielded unusual staining patterns, i.e., V79 cells exposed to PCB3pQ in excess of 7.5 μM exhibited a three-way microtubulin bridge upon cytokinesis. Examples of this rare tubulin effect are shown in Fig. 4.

Figure 4. PCB3pQ alters the spindles of V79 cells.

Cells treated with 10 μM PCB3pQ for 6 h exhibit a 3-pole spindle as seen with other aneuploidy-inducing chemicals in the MN assay.

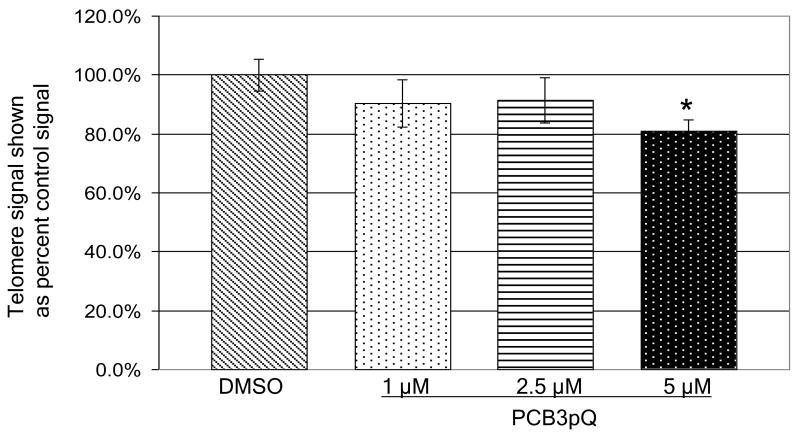

3.2. Telomere Length Reduction in HaCaT cells

For the analysis of effects on telomere length immortal human keratinocytes, HaCaT cells, were exposed for eleven weeks to solvent alone or to 1 μM, 2.5 μM, or 5 μM PCB3pQ. First results using quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) to determine relative telomere length in the PCB3pQ-exposed cells indicate a decrease in telomere signal of approximately 20% in cells exposed to 5 μM PCB3pQ as compared to cells exposed to solvent alone after 11 weeks of continuous exposure, as shown in Fig. 5. A dose-dependent increase in the effect is visible, but was statistically significant only with the highest, 5 μM concentration. During this period, cells divided approximately 70 times in the three PCB3pQ treatment groups and 73 times in the solvent control group, indicating that cell growth was roughly equal between all treatments, varying less than 4 doublings over the 11 week period.

Figure 5. Telomere signal from HaCaT cells as compared to DMSO control determined by qPCR after 11 weeks exposure to the indicated concentrations of PCB3pQ.

Measurements were performed in quadruplicate. Results are calculated as means; error bars represent coefficient of variation. Data are given as percent of control. * denotes statistically significantly different from control (p=0.0102).

4. Discussion

The present study examines the induction of micronuclei by PCB3pQ in V79 hamster lung fibroblast cells. This cell line is commonly used for genotoxicity analysis, since they have a fast cell cycle, they double roughly every 12 hours, have 21 or 22 well defined large chromosomes, and lack mixed-function oxidase expression, which reduces the likelihood that observed effects are due to secondary metabolites. PCB3pQ at non-cytotoxic concentrations produced a strong increase in MN. These findings are in good agreement with previous work performed on hydroxylated and quinone metabolites of benzene and PAHs (Ludewig et al., 1991; Ludewig et al., 1989). The highest concentration tested, 7.5 μM PCB3pQ, also produced a strong cell cycle arrest during exposure in G2/M which was released during the recovery period. This was accompanied by a further increase in MN frequency during the first 6 h of recovery. This correlation could be expected, since MN are only formed when the cell is going through mitosis and losing a chromosome or chromosome fragment during chromosome segregation. Our hypothesis is that PCB quinones interact with the microtubulin or its organization centers (MTOCs), such as centrosomes and basal bodies. Indeed, the induced MN were predominantly CREST-positive, indicating that they contained complete chromosomes. Induction of CREST-positive nuclei and mitotic spindle defects, as shown in Figures 2 and 4, is commonly observed together for many types of chemicals (Lehmann, 2002). It was reported that p-benzoquinone and biphenoquinone bind covalently to SH-groups of microtubulin in vitro (Pfeiffer and Metzler, 1996). It can be assumed that PCB3pQ, which has a high affinity for free SH-groups (Amaro et al., 1996; Srinivasan et al., 2002), also binds to cellular microtubulin thereby inhibiting proper function, resulting in chromosome loss during mitosis.

Effects on telomere length were analyzed in HaCaT cells, a spontaneously immortalized human keratinocyte line that has proven useful for telomere analysis (Zhang et al., 2003). We observed a marked reduction in telomere signal after 11 weeks of exposure to PCB3pQ at 5 μM. Putative telomere shortening in HaCaT cells could be explained by the inhibition of telomerase, which HaCaT cells express for maintenance of the telomeric length (Harle-Bachor and Boukamp, 1996). Telomerase has been demonstrated to be sensitive to helenalin, a compound that, like PCB3pQ, binds preferably to sulfhydryl groups (Huang et al., 2005), and the inhibition of this enzyme would result in progressive loss of telomere length as HaCaT cells proliferate. Increased cell cycling as cause for the loss of telomere length can be excluded, since PCB3pQ-exposed cells underwent nearly the same number of population doublings as the solvent control. To further test our hypothesis that this PCB quinone may cause telomere length reduction by covalent binding to SH-groups of telomerase and inhibiting its function, analysis of specific telomerase activity after PCB3pQ exposure using the quantitative Telomerase Repeat Amplification Protocol is currently being performed.

PCBs negatively influence biological systems in numerous ways. These persistent organic pollutants are suspected to perniciously alter telomeres and microtubulin. We present for the first time data indicating that a quinone metabolite of PCB3 can shorten telomeres and induce micronuclei, possibly through the common mechanism of sulfhydryl binding. It has to be added, however, that a possible alternative mechanism, the generation of reactive oxygen species, could also be involved.

Chromosomal instability, such as aneuploidy, is believed to be a major driving force on the road to cancer (Kops et al., 2005). Telomere shortening has been correlated to chromosomal changes and carcinogenesis (Finley et al., 2006; Maser and DePinho, 2002). As most somatic cells do not express telomerase, the inhibition of this enzyme as a pathological effect has most relevance in human cells retaining telomerase activity such as select cells in the bone marrow, skin, endometrium, gastrointestinal tract, and testis (Bickenbach et al., 1998; Collins and Mitchell, 2002). It is in these cells where the inhibition of telomerase can lead to cellular dysfunction and possibly promote carcinogenesis. Thus, PCB3pQ interference with spindle function with the result of aneuploidy induction in the target cells and telomere length shortening by telomerase inhibition may pose a serious threat to human health.

Acknowledgments

This publication was made possible by grant number P42 ES 013661 from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), NIH, and the University of Iowa Center for the Health Effect of Environmental Contaminants (CHEEC). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIEHS, NIH, or CHEEC. We are grateful to Dr. Hans Lehmler for providing PCB3pQ. We wish to thank Dr. Leane Lehmann, University of Karlsruhe, Germany, and Dr. Harald Esch, BASF, Ludwigshafen, Germany, for their helpful suggestions and help in the laboratory.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Amaro AR, Oakley GG, Bauer U, Spielmann HP, Robertson LW. Metabolic activation of PCBs to quinones: reactivity toward nitrogen and sulfur nucleophiles and influence of superoxide dismutase. Chem Res Toxicol. 1996;9(3):623–9. doi: 10.1021/tx950117e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ATSDR. Toxicological profile for polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) U.S Dept Health Services, Public Health Service; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandele OJ, Osheroff N. Bioflavonoids as poisons of human topoisomerase II alpha and II beta. Biochemistry. 2007;46(20):6097–108. doi: 10.1021/bi7000664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belpaeme K, Delbeke K, Zhu L, Kirsch-Volders M. PCBs do not induce DNA breakage in vitro in human lymphocytes. Mutagenesis. 1996;11(4):383–9. doi: 10.1093/mutage/11.4.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender RP, Ham AJ, Osheroff N. Quinone-induced enhancement of DNA cleavage by human topoisomerase IIalpha: adduction of cysteine residues 392 and 405. Biochemistry. 2007;46(10):2856–64. doi: 10.1021/bi062017l. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickenbach JR, Vormwald-Dogan V, Bachor C, Bleuel K, Schnapp G, Boukamp P. Telomerase is not an epidermal stem cell marker and is downregulated by calcium. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;111(6):1045–52. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1998.00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cawthon RM. Telomere measurement by quantitative PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30(10):e47. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.10.e47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins K, Mitchell JR. Telomerase in the human organism. Oncogene. 2002;21(4):564–79. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lange T, Lundblad V, Blackburn E. Telomeres. Cold Spring Harbor: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Fenech M. The in vitro micronucleus technique. Mutat Res. 2000;455(12):81–95. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(00)00065-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenech M. Cytokinesis-block micronucleus assay evolves into a “cytome” assay of chromosomal instability, mitotic dysfunction and cell death. Mutat Res. 2006;600(12):58–66. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2006.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finley JC, Reid BJ, Odze RD, Sanchez CA, Galipeau P, Li X, Self SG, Gollahon KA, Blount PL, Rabinovitch PS. Chromosomal instability in Barrett's esophagus is related to telomere shortening. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(8):1451–7. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harle-Bachor C, Boukamp P. Telomerase activity in the regenerative basal layer of the epidermis inhuman skin and in immortal and carcinoma-derived skin keratinocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(13):6476–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang PR, Yeh YM, Wang TC. Potent inhibition of human telomerase by helenalin. Cancer Lett. 2005;227(2):169–74. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.11.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirsch-Volders M, Vanhauwaert A, De Boeck M, Decordier I. Importance of detecting numerical versus structural chromosome aberrations. Mutat Res. 2002;504(12):137–48. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(02)00087-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kops GJ, Weaver BA, Cleveland DW. On the road to cancer: aneuploidy and the mitotic checkpoint. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5(10):773–85. doi: 10.1038/nrc1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulling SE, Metzler M. Induction of micronuclei, DNA strand breaks and HPRT mutations in cultured Chinese hamster V79 cells by the phytoestrogen coumoestrol. Food Chem Toxicol. 1997;35(6):605–13. doi: 10.1016/s0278-6915(97)00022-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann L. Untersuchungen zum genotoxischen Potenzial von Substanzen mit estrogener Wirkung. Karlsruhe: Universitaet Karlsruhe (TH); 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lin PH, Sangaiah R, Ranasinghe A, Upton PB, La DK, Gold A, Swenberg JA. Formation of quinonoid-derived protein adducts in the liver and brain of Sprague-Dawley rats treated with 2,2′,5, 5′-tetrachlorobiphenyl. Chem Res Toxicol. 2000;13(8):710–8. doi: 10.1021/tx000030f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludewig G. Cancer initiation by PCBs. In: Robertson LW, Hansen LG, editors. PCBs, Recent Advances in Environmental Toxicology and Health Effects. The University Press of Kentucky; Lexington: 2001. pp. 337–354. [Google Scholar]

- Ludewig G, Dogra S, F S, Seidel A, Oesch F, Glatt HR. Quinones derived from polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: induction of diverse mutagenic and genotoxic effects in mammalian cells. In: Cooke M, Loenning K, Merrit J, editors. Polynuclear Aromatic Hydrocarbons. Bartelle Press; 1991. pp. 545–556. [Google Scholar]

- Ludewig G, Dogra S, Glatt H. Genotoxicity of 1,4-benzoquinone and 1,4-naphthoquinone in relation to effects on glutathione and NAD(P)H levels in V79 cells. Environ Health Perspect. 1989;82:223–8. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8982223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludewig G, Esch H, Robertson LW. Polyhalogenierte Bi- und Terphenyle. In: Dunkelberg H, Gebel T, Hartwig A, editors. Handbuch der Lebensmitteltoxikologie. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH; 2007. pp. 1031–1094. [Google Scholar]

- Maser RS, DePinho RA. Connecting chromosomes, crisis, and cancer. Science. 2002;297(5581):565–9. doi: 10.1126/science.297.5581.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer E, Metzler M. Interaction of p-benzoquinone and p-biphenoquinone with microtubule proteins in vitro. Chem Biol Interact. 1996;102(1):37–53. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(96)03730-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson LW, Hansen LG, editors. PCBs: Recent Advances in Environmental Toxicology and Health Effects. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky Lexington; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan A, Robertson LW, Ludewig G. Sulfhydryl binding and topoisomerase inhibition by PCB metabolites. Chem Res Toxicol. 2002;15(4):497–505. doi: 10.1021/tx010128+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang TC, Schmitt MT, Mumford JL. Effects of arsenic on telomerase and telomeres in relation to cell proliferation and apoptosis in human keratinocytes and leukemia cells in vitro. Carcinogenesis. 2003;24(11):1811–7. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgg141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]