Abstract

Human beings are not only the most sociable animals on Earth, but also the only animals that have to ponder the separateness that comes with having a conscious self. The philosophical problem of ‘other minds’ nags away at people's sense of who—and why—they are. But the privacy of consciousness has an evolutionary history—and maybe even an evolutionary function. While recognizing the importance to humans of mind-reading and psychic transparency, we should consider the consequences and possible benefits of being—ultimately—psychically opaque.

Keywords: consciousness, other minds, social intelligence, self-concept

The word ujamaa in Swahili has no simple translation into English. But its meaning is made plain in the ujamaa carvings created by the Makonde craftsmen of Tanzania. In these carvings, often called ‘trees of life’, human figures, of all sorts and ages, are intertwined in a rising column of ebony (figure 1, Humphrey 1972). Everyone is busy doing their own work: one cooks; another hammers; a third sews; and a fourth nurses her baby. The figures tumble up against each other so closely that their spaces and forms are defined by the bodies of their neighbours. Yet all the time they retain their separate identities and personalities. Ujamaa, it is clear, refers to nothing less than the capacity of human beings, despite their differences, to work together as a community—something that humans are better able to do than any other animal on Earth.

Figure 1.

Makonde tree of life ca 1970.

What gives humans this unparalleled capacity to get along together? What special talent do they have for doing ‘natural psychology’? The answer that I and others have converged on is that there has evolved in the human line, maybe just within the last few million years, a talent and a desire for deep intersubjectivity: a special capacity for mind-reading, underpinned by empathy (the sharing of feelings) and sympathy (the sharing of goals). That is the message of several of the papers in this volume. Humans alone know what it is like to be in someone else's place and humans alone care. That is the message I began to spell out in my 1976 paper on the ‘social function of intellect’ (Humphrey 1976) and developed in Consciousness Regained (1983) and The Inner Eye (1986).

I am not going to tell you that I have changed my mind. However, I do want to use this occasion to pull back a bit, or at any rate to pull in another direction. For I am going to argue here that, in stressing shared consciousness and intersubjectivity, we may be missing something crucial. There is no great truth, it has been said, of which the opposite is not also a great truth. I want to suggest that, when it comes to it, human beings are not only exceptionally sociable, but also exceptionally lonely. And loneliness plays a key part in shaping human life and culture.

But I shall not start with this. For I have a debt, left over from the 1976 paper, that I want to settle first. In the 1880s, long before I or anyone else in evolutionary psychology came on the scene, the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche was already speculating about the very same issues that have engaged the contributors to this volume, about the evolution of consciousness and its relation to social life. I am ashamed to say that I had not read Nietzsche when I wrote my first paper on social intelligence or the papers that soon followed about theory of mind and consciousness. More shameful still, I confess that as an experimental psychologist educated at Cambridge, it never occurred to me that I ought to have read Nietzsche. So, it was not until much too late that I found out how closely Nietzsche's arguments anticipated mine. I suspect what was news to me may still be news to you.

Here is what Nietzsche wrote in The Gay Science (1887/1974):

The problem of consciousness… confronts us only when we begin to comprehend how we could dispense with it… For we could think, feel, will, and remember, and we could ‘act’ in every sense of that word, and yet none of all of this would have to ‘enter consciousness’… The whole of life would be possible without, as it were, seeing itself in a mirror… For what purpose, then, any consciousness at all when it is in the main superfluous? I may now proceed to the surmise that… consciousness is really only a net of communication between human beings; a solitary human being who lived like a beast of prey would not have needed it. That our actions, thoughts, feelings and movements enter our own consciousness—at least a part of them—that is the result of a ‘must’ that for a terribly long time lorded it over man. As the most endangered animal, he needed help and protection, he needed his peers, he had to learn to express his distress and to make himself understood; and for all of this he needed ‘consciousness’ first of all, he needed to ‘know’ himself what distressed him, he needed to ‘know’ how he felt, he needed to ‘know’ what he thought… My idea is, as you see, that consciousness does not really belong to man's individual existence but rather to his social or herd nature.

Nietzsche not only highlighted this role for consciousness, but also had a proposal for precisely how the net of communication is created. Here is what he wrote in Daybreak (1881/1997):

Empathy—To understand another person, that is to imitate his feelings in ourselves, we… produce the feeling in ourselves after the effects it exerts and displays on the other person by imitating with our own body the expression of his eyes, his voice, his walk, his bearing. Then a similar feeling arises in us in consequence of an ancient association between movement and sensation. We have brought our skill in understanding the feelings of others to a high state of perfection and in the presence of another person we are always almost involuntarily practising this skill.

Nietzsche, in short, was ahead of me—and you—in all these ways. First, he formulated the social intelligence hypothesis, realizing that human beings have to be natural psychologists in order to survive. Second, he saw how this would have led to the evolution of a capacity for reflexive consciousness, as the basis for a theory of mind. Third, he recognized how empathy arises from simulation, mediated by imitation of action and expression.

These ideas have come into their own at last. They are being developed at the frontiers of ethology, psychology and neuroscience, as so well illustrated by other papers in this volume, and I have no need to remind you of the buzz that now surrounds them. Of course, the one thing Nietzsche did not anticipate (and nor, I may say, did I) was the existence of mirror neurons. But if anything was needed to give a fillip to the field, Gallese and Rizzolatti's discovery has certainly provided it. Ramachandran (2000) has said ‘I predict that mirror neurons will do for psychology what DNA did for biology’. In a recent article, Gallese et al. (2004) bill mirror neurons as providing ‘a unifying view of the basis of social cognition’. A headline in the New York Times calls these neurons ‘cells that read minds’ (Blakeslee 2006); and in the article that follows, Marc Iacoboni is quoted as claiming: ‘you automatically have empathy for me. You know how I feel because you literally feel what I am feeling’.

Indeed, neuroscience itself is beginning to be wonderfully in touch. In 2005, the Dalai Lama was cheered to the rooftops at the Society for Neuroscience in Washington, when he explained the relevance of Buddhist ideas about the connectedness of everything. Typical of this new trend, a recent conference in Bologna addressed ‘primordial questions about consciousness’, centred on the question ‘do you have a pragmatic proposal to make first-person experience intersubjectively shareable?’ (ASIA 2006). It seems that the ideas about flow and connectedness are fast becoming not just politically but scientifically correct. If I do not feel your pain—or at any rate have a pragmatic proposal for feeling it—then I had better not let on!

Now, do not get me wrong. I would be the first to agree that the field of consciousness studies has entered an exceptionally exciting phase. Yet with the social brain and mirror neurons all the rage, I do think there is a danger that in the rush to emphasize empathy as a human birthright, we may be failing to recognize—perhaps even wilfully failing to recognize—the extent to which consciousness creates barriers between people, even as it unites them.

In both my early books, I used paintings by Paul Gauguin to illustrate what it means for us to look into and read another person's mind. Gauguin, writing of his 13-year-old wife, had said ‘I strive to see and think through this child’. And the stated aim of many of his paintings was to understand the mystery of things and people by going inside them to reveal the deep structures that make them what they are. Likewise, I suggested, ordinary human beings are continually doing something similar to this in their daily social life. ‘We all, every day of our lives, imagine more than we can see… And we do it most impressively and most importantly when—almost without noticing it—we make imaginative guesses about the hidden contents of the human mind. We have only so much as to glance at another human being and we at once begin to read beneath the surface. We see there another conscious person, like ourselves. We see someone with human feelings, memories, desires. A mind potentially like ours’ (Humphrey 1986, p. 30).

But I should have looked more carefully, for now I think that my choice of Gauguin to illustrate the case of mind-reading was a perverse one. Gauguin as a painter was indeed a genius at going ‘behind appearances’ to reveal hidden meanings. But what he revealed about human society is actually very far from that legendary net of communication between human beings.

Within a year of arriving in Tahiti in 1891, Gauguin had made a carving with an uncanny resemblance to a Makonde tree of life (figure 2; Gauguin 1893a). It seems probable that he had in fact seen a Makonde carving, when he visited the Colonial Exhibition in Paris in 1889, where many works of African art were on display. In Gauguin's carving, as in the Makonde model, the figures line up next to each other, sharing the same bit of wood. However, that is where the resemblance ends. For Gauguin has done nothing to convey the spirit of ujamaa. The figures in his carving, rather than communicating, are more like straphangers in a crowded tube train, physically close but mentally shut off.

Figure 2.

Paul Gauguin, ironwood carving 1893.

The absence of human communion is in fact one of the most striking features of Gauguin's representation of people in his Tahitian paintings (figure 3; Gauguin 1896). In the paintings, individuals never touch, nor hardly even look at each other. In stark contrast to a tree of life, each occupies his or her own mental world, private and separate. What Gauguin seems to want to stress is the psychological distance between people, the extent to which everyone remains an enigma to everyone else. Indeed, as if to underscore this, he gives titles to the paintings in the form of uncomprehending questions about what is going on: ‘Why are you angry?’; ‘What, are you jealous?’; and ‘When will you marry?’.

Figure 3.

Paul Gauguin, Why are you angry? 1896. (Reproduced with permission from the Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL).

These are paintings, I would now say, about the ‘otherness of other people’. This phrase is one I have borrowed from John Banville (2005), in his novel, The Sea. Speaking of the girl he was obsessed with, the narrator writes, ‘In her [Chloe], I had my first experience of the absolute otherness of other people. It is not too much to say—well it is, but I shall say it anyway—that in Chloe the world was first manifest for me as an objective entity… I never knew where I was with her, or what sort of treatment to expect at her hands’.

Let us note—it is important—that Chloe in this novel is no stranger to the narrator, no more than the people in Gauguin's paintings are strangers to each other. In fact, it seems to be part of the point being made by both novelist and painter that it is precisely when people get closest to others, and have come to know them well as familiar objective entities, that their psychological otherness becomes most obvious—and most alarming.

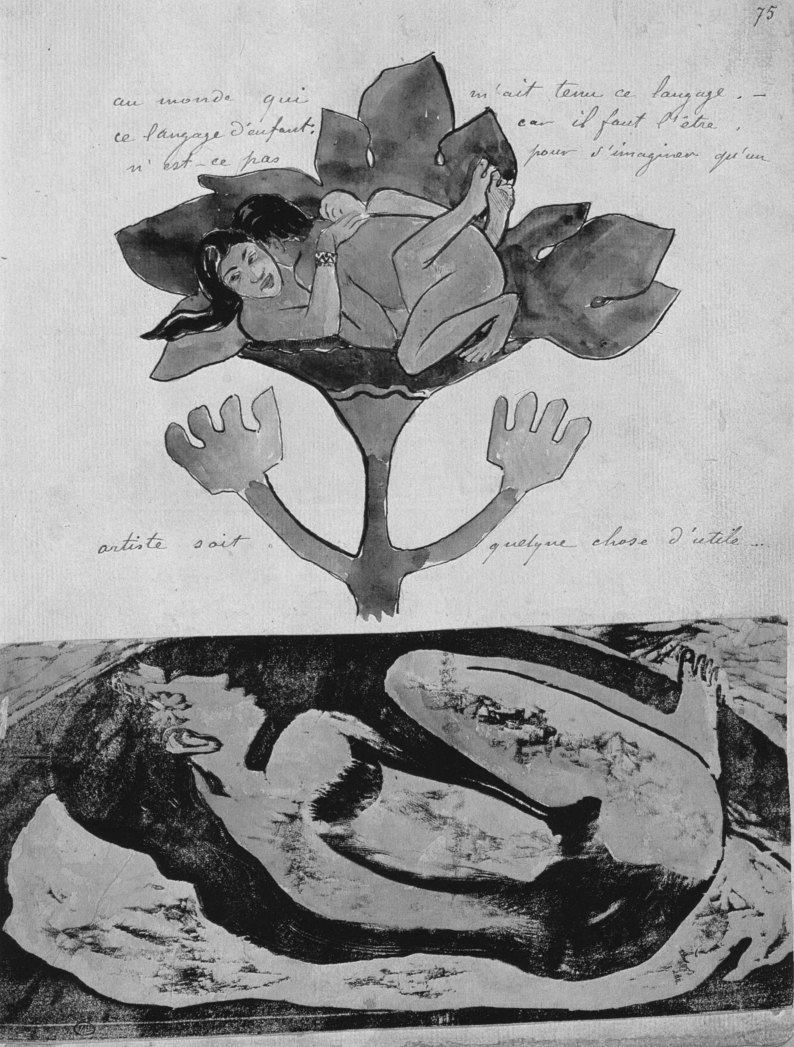

Sexual intimacy, in particular, can provide a worrying test. As Gauguin revealed in his letters and diaries, sex was never far from his thoughts. While rooming with Van Gogh in the Yellow House in Arles, he made provision in their joint budget for regular outings to prostitutes for what he called ‘hygienic excursions’ to satisfy his insistent manhood. He did it, it seems, primarily for health reasons, and perhaps this was just as much true after he moved to Tahiti. Gauguin made only one picture of the act of sex. But it is a revealing one. The woman looks up and away, her mind quite clearly somewhere else (figure 4; Gauguin 1893b). In several paintings of his young wife in Tahiti, he shows her lying on her bed, post-coitus, the very picture of solitariness.

Figure 4.

Paul Gauguin, illustration to Noa Noa. (Reproduced with permission from Musée du Louvre, Paris, France; photograph © Hervé Lewandowski).

Possibly, Gauguin was unusually cavalier in his attitude to making love. Even so, the fact is that for all too many couples, sexual intercourse is actually a lesson in mental separateness, carnal knowledge a lesson in spiritual agnosia. Dryden (1684), in a translation of a poem by Lucretius, spelt out this stark reality:

They gripe, they squeeze, their humid tongues they dart,

As each would force their way to t'others heart:

In vain they only cruze about the coast,

For bodies cannot pierce, nor be in bodies lost…

All ways they try, successless all they prove,

To cure the secret sore of lingring love.

The poet W. B. Yeats called these lines ‘the finest description of sexual intercourse ever written’—precisely because they illustrate just how impossible it is for two to become a unity. ‘The tragedy of sexual intercourse’, Yeats said, ‘is the perpetual virginity of the soul’ (Yeats 1949).

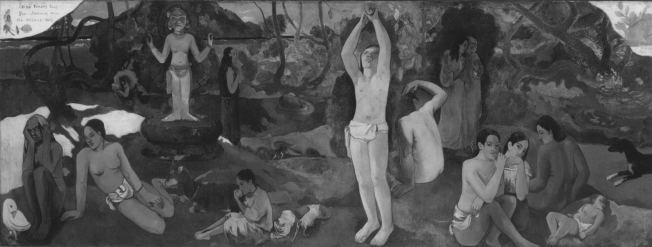

By the end of 1897, Gauguin had had enough. His hopes of discovering the essence of being human—through love, through friendship, through history—seemed to have come to nothing. He was disillusioned and depressed, and wanted to die. Still, in a last effort to make a grand statement of his ethical discoveries, he completed in a fever of work the biggest of all his paintings, and wrote on it—he said it was his signature—D'où Venons Nous, Que Sommes Nous, Où Allons Nous (figure 5; Gauguin 1897). Then, on New Year's Eve, he climbed the hill behind his house with a box of arsenic in his pocket, with the intent of killing himself. In this event, he took too much of the poison and vomited it up. After lying out a few hours, he dragged himself disconsolately home.

Figure 5.

Paul Gauguin, Where do we come from? What are we? Where are we going? 1897. (Reproduced with permission from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA).

Gauguin's attempt at suicide failed. But his attempt at revealing in this last picture something profound about what it's like to be a human being certainly succeeded. There have been a thousand interpretations of this painting. But I have no hesitation in telling you my own. What the puzzled, isolated figures of the painting speak to is the essential loneliness of the human condition.

Que sommes nous? What are we? The bottom line is that we are not a we. We are a set of I's… individuals who due to the very nature of conscious selfhood are in principle unable to get through to one another and share the most central facts of our psychical existence. Nietzsche was wrong. When it comes to consciousness, we are on our own: ‘soul’, ‘solo’. Etymologically, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, there is no connection between soul as a noun and sole as a predicate (though I may say I wonder). But psychologically and even logically, the connection is all too clear. There are no doors between one consciousness and another. Everyone knows directly only of his or her own consciousness and not anyone else's.

It is all so horribly obvious, when you think about it. And we do think about it. Since we were children, we have all played with the riddles of otherness that flow from the essential inaccessibility of other minds. To take John Locke's famous example of seeing colours: how do I know that my colour sensation when I see a violet is not like yours when you see a marigold. The answer, which it has never required a great philosopher to prove to us, is simply that I do not—because, as Locke said, ‘one man's mind cannot pass into another man's body’ (Locke 1690/1975). Of course, probably we long ago ceased to find this conclusion novel. Yet there is no denying how strange and upsetting it was—and is—at first discovery: not simply an interesting tease but a gaping hole at the centre of our need for communion.

If I cannot even tell what seeing red is like for you, what can I tell! Imagine. We are walking together in the woods after the rain, dappled sunshine filters through the dripping leaves, a blackbird sings and the scent of honeysuckle permeates the rich air. It may be that shared moments like these are needed to give meaning to our lives—shared moments of consciousness. What then if we should realize how little we are truly sharing: that if truth be told each of us is merely colouring in the other's consciousness as if it were his or her own?

I suggest that what Gauguin was showing in that last great painting is just how hard it is to come to terms with this result. To have to face the fact of being oneself—one self, this self and none other, this secret packet of phenomena, this singular bubble of consciousness. Press up against each other as we may, and the bubbles remain essentially inviolate. Share the same body even, be joined like Siamese twins, and there still remain two quite separate consciousnesses (figure 6, Beloit 2006). Perhaps, the tragedy of being human is the perpetual virginity of the soul.

Figure 6.

Siamese twins, woodcut from the Nuremberg Chronicle, 1493.

But how funny all this is. I mean funny-peculiar. Nothing else in the world is private in quite the same, disturbing, way that conscious experience is. Everything else in the world joins up in the four-dimensional space–time manifold that basic physics says is sufficient to describe the universe. But consciousness it seems is essentially different. Indeed, each individual's consciousness would seem to be as much a world apart, on its own plane of existence, as is each separate universe in the ‘multiverse’ that cosmologists sometimes fantasize about. Let alone are there open doors between one conscious self and another; it seems there is not even the possibility of tunnelling though a wormhole.

It is hardly surprising that many ordinary people find this situation puzzling, even paradoxical. This puzzlement is not because they are missing something—not because they are making a category error, or because they do not know how to talk properly (though some philosophers persist in saying so). Consciousness really is deeply, fascinatingly, peculiarly private. And the meaning and explanation of this privacy continues to pose a major challenge to cognitive science and philosophy of mind.

My own approach as a scientist (Humphrey 1992, 2000, 2006) has been to look for an explanation for the privacy of consciousness in its deep evolutionary history. That is to say, I have tried to explain how consciousness could have evolved, little by little, always under natural selection, to be so constructed as to be private. In fact, I have argued that it has evolved to be private on two quite different levels. Consciousness has become private—necessarily private—on the phenomenal level: meaning that one person cannot in principle have access to another person's subjective awareness of what it is like to be conscious, to be sensing red, for example. But then consciousness has also become private—contingently private—on the propositional level: meaning that one person usually does not have access even to the objective fact that another person is sensing red.

This is not the place to go into this theory of consciousness in any great depth. But, still, if I may move to a more analytic kind of discussion for a moment, I shall try to summarize what I think the story is. And I will begin with an analogy.

When a person, let us say it is me, performs a bodily action, when I wiggle my right big toe, for example, there are two respects in which this action is something that uniquely belongs to me and/or that I have a unique take on. First, it is I only who am doing it, I am its author—and, of course, no one else does or logically could stand in this first-person subjective relation to the action of wiggling my toe. Thus, the doing of it is necessarily private. I cannot give away my action or share it even if I want to. True, you might perform a similar action with your body. You might even perform it at the very same time as I do. But, still, you would not be wiggling my toe, you would be wiggling yours.

Second, it is my body that is involved, the body to which I have a special spatio-temporal relationship—and so I can hardly miss the fact that the wiggle is occurring. True, I am not the only one who could, in principle, make this observation as an objective fact. If I am acting in public, it is logically possible you too could observe that I am wiggling my toe. But suppose I perform the action covertly, inside my boot, say. Then everyone else except me will be out of the observational loop. Thus, many of the observations I am able to make about my actions will be contingently private. I could, in principle, share the objective information with you, but in many cases I will not have to and will not choose to.

Now, how does this tie in with consciousness? What could my unique take on my bodily actions have to do with my unique take on my conscious sensations? What can the private nature of wiggling my toe have to do with the private nature of seeing red, or smelling a rose, or feeling pain? According to the theory I have developed, it can have everything to do with it: because sensations actually are a kind of bodily action—or, at any rate, they were. Sensations are not things that happen to us, they are indeed things we do.

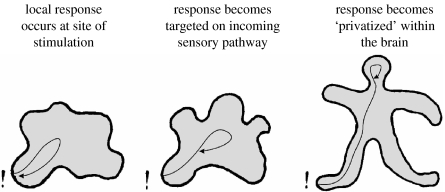

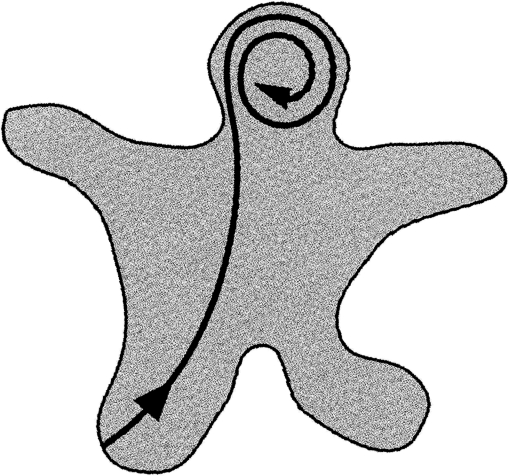

When I look at a red screen, for example, I respond to what is happening at my eyes with a pattern of bodily activity that originated far back in evolutionary history as an instinctive evaluative response to the stimulus. In the beginning, such responses were indeed public behaviour—bodily expressions of liking or disgust, wriggles of acceptance or rejection. They would have been there for anyone to see. However, what happened in the course of evolution was that these responses became ‘privatized’: they began to get short-circuited before they reached the body surface, so that the motor signals instead of reaching all the way out to the site of stimulation now reached only to points closer and closer in on the incoming sensory nerve, until eventually the whole process became closed off from the outside world. In fact, the efferent signals now project only as far as sensory cortex, where they interact with the incoming signals from the sense organs to create, momentarily, a self-entangling, recursive loop (figure 7).

Figure 7.

The ‘privatization’ of sensation (from Humphrey 2006, p. 95).

The upshot is that when looking at the screen, I am still responding to the stimulation with something like the ancient action pattern handed down from my ancestors. The action still retains vestiges of its original evaluative function, its intentionality and hedonic tone. But now it has become a ‘virtual action pattern’—an as-if response directed to an as-if body, hidden inside my head.

So, now, for me to be phenomenally conscious of having the sensation, for there to be something it is like to be doing this, is nothing more or less than for me to be actively engaged in generating this as-if response—as extended, by the recursion, into the ‘thick moment’ of the conscious present. Meanwhile, for me to have the propositional part of the experience, to observe that I am having a red sensation, is simply for me to monitor the fact that I am so engaged.

Whence, then, the privacy of consciousness? Think back to the analogy of my wiggling my toe. If the theory is right, the necessary privacy of the phenomenal experience is guaranteed by the fact that the sensation is my doing. When I generate sensations, I experience the subjective qualia from a perspective which as a matter of principle is not available to any one else. This would be so even if the sensory responses had not been internalized. But they have been. So, the contingent privacy of the propositional part of the experience is guaranteed by the fact that my sensory responses are no longer public. Only I can observe that I am having a particular sensation because only I can observe what I am creating inside my head.

The point is not that you could not know that I am doing it, merely that in most circumstances you will not know—unless perhaps you can infer it from some external cue. If you do infer it, this could indeed lead to your mirroring the sensory response in your own brain. But note that this will not give you access to my phenomenal experience. Through mirroring the sensory response, you may indeed learn that I am sensing red, you may sense red yourself, but it will be you sensing your red.

So, has anyone got a pragmatic proposal to make first-person experience intersubjectively shareable? In the light of this analysis, you will see why I do not hold out much hope that any scientist or philosopher will ever be able to give the Buddhists the answer they want. ‘I feel your pain’? No, when you are in pain, I may or may not recognize that you are feeling pain, I may indeed feel my own mirror version; but your pain remains strictly inalienable.

Consider again the case of Siamese twins. It is a matter of record—I mean the twins will tell anyone who asks—that their conscious minds are as private as the next person's. Does one conjoined twin know what it is like for the other twin to have a headache? No, yes, maybe, can't be sure…no more than you or I do. Oftentimes, one twin will not even know that the other has a headache. I confess, despite all my theorizing, I still find this fact astonishing.

So, let me return to society and trees of life. The fact is ordinary people have never needed any of this analysis to know the score. They have had a lifetime to check it out first hand. How was it for you? I presume that the honest answer will always have been ‘virginal’—because there is simply no other way for it to be.

Yet, if the virginity of the soul is a reality, is it necessarily such a tragedy? I would say there are evolutionary grounds for thinking that it cannot be too much of a tragedy. For, if it were, then natural selection would never have allowed things to develop in the way they have done. To the contrary, the fact that natural selection has allowed it, even arranged for it, would suggest that the inaccessibility of consciousness may even be in some respects positively advantageous. However, in that case, there will be two separate questions to address: one, the advantage of the contingent privacy of propositional consciousness; the other, the advantage of the absolute privacy of phenomenal consciousness. And the first is much easier to deal with than the second.

As to the first, I expect many readers will already have run ahead of me. For it must be obvious enough to anyone steeped in sociobiology why a social animal such as a human being would be better off if it were to have at least the possibility of keeping the existence of its thoughts and feelings to itself. The capacity for mind-reading and for being mind-read is all very well. But human individuals even in the closest knit cooperative groups are still usually to some degree in competition. So there must certainly be times when individuals do not want to be a completely open book to others. Paul Valéry, the poet, made the point as succinctly as any of us might want to: ‘credit requires that walls of coffers be opaque, and the interchange of human things between men requires that brains be impenetrable’ (Valéry 1983). The advantages of tactical deception, as other chapters in this volume testify, are obvious even in apes and crows. If consciousness does provide a net of communication, nonetheless there is clearly much to be said for facultative privacy—for having the option of being able to logout and go off-line.

But now for the second question, about the absolute privacy of phenomenal consciousness. Could there be anything to be said for consciousness being so structured that individuals cannot share key aspects of their experience even if they want to? Let me explain just what it is I am asking here, for I expect most readers will in this case think the answer must be No. Could the fact that, for example, I must for ever be unsure whether what I experience as the sensation of red is the same as what you experience conceivably change my life in a positive way? Could it make any difference at all?

It is worth noting what John Locke (1690/1975) had to say. The passage in his Essay where he sets up the thought experiment about one man's marigold being another man's violet is quite well known.

[Suppose] the idea that a violet produced in one man's mind by his eyes were the same that a yellow marigold produced in another man's, and vice versa. This could never be known: because one man's mind could not pass into another man's body, to perceive what appearances were produced.

But the passage that immediately follows this is hardly known at all. Surprisingly, Locke goes on to deny that colour inversion is a possibility worth taking seriously.

I am nevertheless very apt to think that the sensible ideas produced by any object in different men's minds, are [in fact] indiscernibly alike. For which opinion there might be many reasons offered: but being besides my present business, I shall not trouble my reader with them: but only mind him that the contrary supposition, if it could be proved, is of little use, either for the improvement of our knowledge, or convenience of life.

Shades of the mathematician Fermat here (‘I have a truly marvellous proof of this proposition which this margin is too narrow to contain’). But I think the fact is Locke has simply lost his philosophical nerve. And he is wrong to have done so. For in truth, neither he nor anyone else has ever been able to offer the reasons he alludes to why colour sensations have to be alike. Even Ludwig Wittgenstein would later concede in the Philosophical Investigations (1958):

The essential thing about private experience is really not that each person possesses his own exemplar, but that nobody knows whether other people also have this or something else. The assumption would thus be possible—though unverifiable—that one section of mankind has one sensation of red and another section another.

However, central to my present business, I think Locke was wrong on another score, as well: namely, in saying that it is all of little consequence—‘of little use for the convenience of life’. To the contrary, I believe the realization that other people may possibly experience the world differently is potentially life transforming.

How can that be? It is true of course that a difference between people, that is, as Wittgenstein says ‘unverifiable’, has to be a difference that makes no difference. Yet, this does not mean that the possibility of such a difference can make no difference. For why should it not be that what makes the difference is precisely what someone makes of this possibility?

Consider the following analogy. Imagine two men, A and B, each of whom has a private box with a clock in it, which he can use to tell the time. Their clocks are identical except for one peculiar feature: namely, that while the hands on A's clock turn in a clockwise way, the hands of B's turn in an anticlockwise way. When A and B read their clocks, they agree about what time it is, about the rate time is passing and so on. So it would seem that the direction of rotation is just such a difference that makes no difference. But, wait for it. Suppose A were to think: ‘I wonder what it is like to be B watching his clock’—only to realize that he has no way of knowing whether B's clock rotates like his own or in the opposite direction. ‘That's weird, B could be clockwise like me or anticlockwise, and I wouldn't know!’ Now, suppose A were to find this situation challenging. Suppose A were to be upset that he does not know about B, or perhaps pleased as Punch that B does not know about him. Then here we would have a difference that makes no difference—but which makes a difference precisely because A realizes it makes no difference.

My point is that this is very much how it is with sensations. Conscious human beings find themselves landed in a situation where the realization that they cannot know what phenomenal consciousness is like for other people may itself have a significant impact on what they think and what they do. The absolute privacy of consciousness may strike them as provocative, tantalizing, alarming, awe-inspiring, all of the above—but one way or another it will matter to them, and so in large or small ways it may change their attitude to other people, to themselves and to the world.

I would suggest that there are two possible human responses to this situation that are of particular interest to an evolutionist. One is that people find it unacceptable, something to be denied or resisted. The other is that they find it wonderful, something to be celebrated.

So far, I have stressed only how unhappy it may make people to realize how solitary the soul is. Gauguin tried to kill himself. The poet John Clare, sadly complaining ‘I am; but what I am none knows or cares’, went quietly mad. Others, finding the whole thing too bewildering or too depressing to think about, push it aside or pretend they do not care. Clearly, no advantage comes from such responses. But there is another way of dealing with the problem—and that is to fight it, to struggle to get through to each other all the same.

I said there are no wormholes between conscious minds. Really there are not. But this does not stop people avidly searching for them. Indeed, the attempt to defeat the reality and find just such holes—or even open doors—underlies many of the most heroic efforts of human culture. Religious beliefs and practices pointedly stress spiritual communion, especially in a life to come. Group rituals and entertainments bring people together in the here and now: dancing together; singing together; and worshiping together. As bodies move in synchrony, minds may indeed get as close as they ever can to being united. Thanks to the existence of mirror neurons, it kind of works. Even if these communal activities bring people less close than they would hope—even if ‘kind of working’ is never quite enough—the quest will often prove beneficial, doing good things for social cohesion on other levels.

But the second way of responding to the situation is just the opposite, and potentially of even greater evolutionary significance. Instead of either running from the problem or trying to mend it, why not make the most of it? Just look what we've got here! If I myself have this astonishing phenomenon, known only to me, at the centre of my existence, and if (it is, of course, a big if) I can assume that you do too, then what does this say about the kind of people that we are? It is not just me. Each of us is a creative hub of consciousness, each has a soul, no one has more than one. All men have been endowed by the creator with an inalienable and inviolable mind-space of their own.

We are a society of selves. The idea that everyone is equally special in this way is extraordinarily potent—psychologically, ethically and politically. And I dare say it would be and is highly adaptive. I believe it is likely to have arisen within the human community as a direct response to reflecting on the remarkable properties of the conscious mind. And from the beginning, it will have transformed human relationships, encouraging new levels of mutual respect, and greatly increasing the value each person puts on their own and others' lives. Indeed, I would go so far as to suggest that it marked a watershed in the evolution of our species—the beginning of humanity's interest in the human project, a concern with humanity's past and humanity's future.

There is another Swahili word, ubuntu, that complements ujamaa. Desmond Tutu, the brave champion of human rights, gives this explanation (Tutu 2006): ‘[it] is the idea that you cannot be human in isolation… You are human precisely owing to relationships: you are a relational being or you are nothing.’ But this is in no way contrary to what I am saying here. Human beings need relationships. But the deepest and best relationships are going to be those between people who recognize the existence in others of a conscious self that is as strange and precious—and private—as their own.

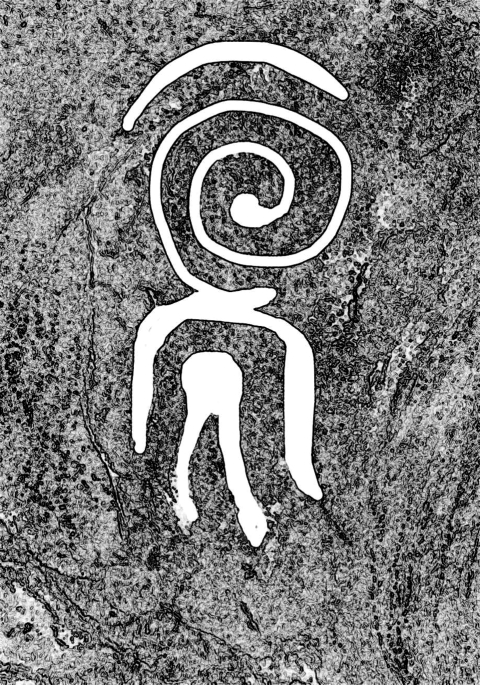

Can we say when historically this may have come about? Not yet. But I think that the archaeological record could still provide clues. In the village of Villafamés, in the Valencia region of Spain, there are some rock paintings in a cave just below the castle, dating to ca 15 000 years ago. When I visited the cave in 2006, I was taken aback to see the resemblance between one of the images (figure 8 UNESCO, 1998) and a drawing I made some years ago to illustrate the privatization of sensation (figure 9). Was this rock painting an early Neolithic representation—and celebration—of what it means to have a self?

Figure 8.

Rock painting, Villamés, Valencia, Spain.

Figure 9.

Figure from Humphrey (2000, p. 249).

Footnotes

One contribution of 19 to a Discussion Meeting Issue ‘Social intelligence: from brain to culture’.

References

- ASIA 2006 Primordial questions about consciousness: a dialogue among science, philosophy and religion Centro studi ASIA, Bologna, June 25–July 1st 2006. http://www.associazioneasia.it/csa/index.html

- Banville J. The sea. Picador; London, UK: 2005. pp. 167–168. [Google Scholar]

- Beloit 2006 Woodcuts from the Nuremberg Chronicle, CCXVIIr, 1493. Morse Library, Beloit College, http://www.beloit.edu/~nurember/book/images/Miscellaneous/index.htm

- Blakeslee, S. 2006 Cells that read minds. New York Times, January 10.

- Dryden J. Keats and embarrassment. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 1684. Translation of book IV of Lucretius. Quoted in Christopher Ricks, 1976. p. 64. [Google Scholar]

- Gallese V, Keysers C, Rizzolatti G. A unifying view of the basis of social cognition. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2004;8:396–403. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2004.07.002. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2004.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauguin P. Ironwood, mother of pearl, bone. Private collection, France. Illustrated in Nicholas Wadley, 1985, Noa Noa: Gauguin's Tahiti. Phaidon; London, UK: 1893a. Idol with a shell. p. 111. [Google Scholar]

- Gauguin, P. 1893b Lovers. From Noa-Noa, p. 75. Louvre ms. © Musée du Louvre.

- Gauguin, P. 1896 Why are You Angry? (No Te Aha Oe Riri) Oil on canvas. Mr. and Mrs. Martin A. Ryerson Collection. 1933.119. The Art Institute of Chicago. © The Art Institute of Chicago.

- Gauguin, P, 1897 Where have we come from, What are we, Where are we going? (D'où Venons Nous, Que Sommes Nous, Où Allons Nous?) Oil on canvas. Tompkins Collection. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

- Humphrey, N. 1972 “Tree of Life”, ebony, height 27 cm, Makonde tribe, purchased Nairobi 1972, collection of the author.

- Humphrey N. The social function of intellect. In: Bateson P.P.G, Hinde R.A, editors. Growing points in ethology. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 1976. pp. 303–317. [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey N. Consciousness regained: chapters in the development of mind. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey N. The inner eye. Faber & Faber; London, UK: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey N. A history of the mind. Chatto & Windus; London, UK: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey N. The privatization of sensation. In: Huber L, Heyes C, editors. The evolution of cognition. MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 2000. pp. 241–252. [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey N. Seeing red: a study in consciousness. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Locke, J. 1690/1975 An essay concerning human understanding (ed. P. Nidditch), Bk.II, Ch. XXXII, sect. 15. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press.

- Nietzsche, F. 1887/1974 The gay science (transl. W. Kaufmann), 354, pp. 297–300. New York, NY: Vintage Books.

- Nietzsche, F. 1881/1997 Daybreak (transl. R. J. Hollingdale), Book II, 142, p. 89. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Ramachandran, V. S. 2000 Mirror neurons and imitation learning as the driving force behind “the great leap forward” in human evolution. EDGE http://www.edge.org

- Tutu, D 2006 Reflections on the divine. New Scientist, 29 April.

- UNESCO 1998 Rock painting, listed (but not illustrated) as Unesco World Heritage Site 874-359, http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/874 The image here was traced by the author from a photograph. Height 25 cm.

- Valéry, P. 1983 Quoted by P. Johnson-Laird, Pictures of Ourselves, London review of books, 22 December, p. 20.

- Wittgenstein, L. 1958 Philosophical investigations (transl. G. E. M. Anscombe), Part I, 272, Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

- Yeats W.B. Keats and embarrassment. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 1949. Quoted in Christopher Ricks, 1976. p. 64. [Google Scholar]