Abstract

PcrA helicase, a member of the superfamily 1, is an essential enzyme in many bacteria. The first crystal structures of helicases were obtained with PcrA. Based on structural and biochemical studies, it was proposed and then generally believed that PcrA is a monomeric helicase that unwinds DNA by an inchworm mechanism. But a functional state of PcrA from unwinding kinetics studies has been lacking. In this work, we studied the kinetic mechanism of PcrA-catalysed DNA unwinding with fluorometric stopped-flow method under both single- and multiple-turnover conditions. It was found that the PcrA-catalysed DNA unwinding depended strongly on the PcrA concentration as well as on the 3′-ssDNA tail length of the substrate, indicating that an oligomerization was indispensable for efficient unwinding. Study of the effect of ATP concentration on the unwinding rate gave a Hill coefficient of ∼2, suggesting strongly that PcrA functions as a dimer. It was further determined that PcrA unwound DNA with a step size of 4 bp and a rate of ∼9 steps per second. Surprisingly, it was observed that PcrA unwound 12-bp duplex substrates much less efficiently than 16-bp ones, highlighting the importance of protein-DNA duplex interaction in the helicase activity. From the present studies, it is concluded that PcrA is a dimeric helicase with a low processivity in vitro. Implications of the experimental results for the DNA unwinding mechanism of PcrA are discussed.

INTRODUCTION

Helicases are a ubiquitous class of motor proteins that use the energy of nucleotide triphosphate hydrolysis to translocate along and separate (unwind) the complementary strands of nucleic acid duplex. These enzymes play essential roles in many cellular processes such as DNA replication, repair, recombination, transcription and thus are involved in most aspects of DNA and RNA metabolism (1–5).

Up to now, many helicases from different living organisms have been identified and studied. Besides their biochemical properties and cellular functions, their DNA unwinding mechanism is a research topic of great interest. One of the major concerns in studying the DNA unwinding mechanisms of helicases is their oligomeric states. Various biophysical and biochemical studies including crystal structures have shown that some helicases are active as oligomers. For example, certain helicases assemble into a stable cooperative hexameric rings (6), such as the DnaB helicase from Escherichia coli (7), the bacteriophage T4 gp41 (8,9) and T7 gp4 (10,11) helicases. One strand of the duplex DNA passes through the central channel of such a hexameric ring and the DNA is unwound with a high processivity. Kinetic studies have shown that the E. coli Rep helicase functions as a dimer (12,13). Single-molecule measurements have verified that a Rep monomer cannot initiate DNA unwinding though it is capable of translocating along ssDNA (14,15).

Whether helicases can function as monomers had once been a question of great debate. But recently more and more evidences have shown that some helicases such as RecG (16), Dda (17,18), RecQ (19,20) and NS3h (21) may function as monomers. For some of the helicases with available crystal structures, such as NS3h (22), RecG (23) and the C-terminal truncated RecQ (24), the conclusions are consistent with their crystal structures.

The focus of this study is the kinetic DNA-unwinding mechanism and the active state of the superfamily 1 helicase Bacillus stearothermophilus PcrA. PcrA is an essential enzyme in many bacteria involved in processes such as DNA repair and rolling circle replication (25,26). The first helicase crystal structures were obtained with B. stearothermophilus PcrA (27). Based on the crystal structures of the apo form of PcrA and PcrA in complex with nucleotides and DNA (27,28), Wigley and his colleagues (29−32) have found that the PcrA helicase may function as a monomer and the available structural and biochemical properties of it can be explained by an inchworm mechanism.

It should be noted, however, that systematic kinetics studies of the DNA unwinding behaviours of PcrA in support of its monomeric form are as yet unavailable. Such studies are complementary to structural investigations and have been widely used for determining the active forms of various helicases, such as Rep (13), UvrD (33,34), Dda (17,18), NS3h (21) and RecQ (20). Interestingly, the helicase E. coli Rep, which shares significant homology (41% identity) and has tertiary structures (35) similar to B. stearothermophilus PcrA, is found through various kinetics and single-molecule studies as a dimeric helicase, as just mentioned before. For another SF1 helicase with similar sequence homology (44% identity), E. coli UvrD, though previous mutational and recent structural studies suggest that it may be a monomeric helicase (36,37), systematic DNA unwinding kinetics studies demonstrate that it may be also a dimeric helicase (33,34). This implies that some discrepancy may exist between the different approaches on determining the active form of a helicase. Considering the fact that the crystal structures of PcrA in complex with nucleotide and ss/dsDNA (28) are almost the same as that of UvrD (37), we are wondering whether the PcrA helicase may actually function as oligomers or, more concretely, dimers in DNA unwinding. Indeed, very recently, Niedziela-Majka et al. (38) have shown that B. stearothermophilus PcrA monomers are able to translocate along ss-DNA, in the 3′ to 5′ direction, rapidly and processively, whereas those same monomers fail to catalyse DNA unwinding under the same solution conditions.

In this study, we resorted to rapid stopped-flow fluorescence assays to examine the oligomeric state of PcrA in DNA unwinding. The assays were based on the fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET), allowing continuous and real-time observations of the unwinding process (12). PcrA-mediated unwinding kinetics was analysed systematically under both single- and multiple-turnover conditions. We provide strong evidence that the active form of PcrA may be a dimer at least in vitro.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and buffers

All chemicals were reagent grade and all buffers were prepared in high quality deionized water from a Milli-Q Ultrapure Water Purification Systems (Millipore, France) having resistivity greater than 18.2 MΩ.cm. All unwinding reactions and DNA binding assays were performed in buffers containing 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5 at 25°C), 50 mM NaCl and 2 mM MgCl2, unless noted elsewhere. ATP was from Sigma (USA) and dissolved as a concentrated stock at pH 7.0. The ATP concentration was determined by using an extinction coefficient at 259 nm of 1.54 × 104 cm−1 M−1.

PcrA protein and oligonucleotide substrates

Bacillus stearothermophilus PcrA protein was expressed and purified according to Bird and colleagues (29). Its purity was determined by SDS–PAGE analysis and was found to be >98% (Fig. S1, Supplementary Data). The PcrA concentration was determined spectrophotometrically using a calculated extinction coefficient of 0.76 OD280/mg/ml/cm.

The DNA substrates used in the unwinding assays had both strands labelled with fluorescein (F) and hexachlorofluorescein (H), respectively, whereas that used in the polarization anisotropy assay had only the top strand labelled with fluorescein. Their structures and sequences are shown in Table 1. The ssDNA substrates used in the DNA binding assay had no fluorescent labels. The protein trap used in the single-turnover kinetic experiments was 56 nt poly(dT), dT56.

Table 1.

DNA substrates used in DNA binding and unwinding assays

| Substrates | Structure and sequence (5′ to 3′) |

|---|---|

| For equilibrium ssDNA binding | |

| 8-nt ssDNA | TAG CAG TT |

| 16-nt ssDNA | CTC TGC TCG ACG GAT T |

| 26-nt ssDNA | AAT CCG TCG AGC AGA G (dT10) |

| 35-nt ssDNA | AAA AAA AAA ACT TCG TTT GGC GAC GGC AGC GAG GC |

| 40-nt ssDNA | AAA AAA AAA AGT AAC CTT CGT TTG GCG ACG GCA GCG AGG C |

| 56-nt ssDNA | AAT CCG TCG AGC AGA G (dT40) |

| For DNA unwinding | |

| 12-bp duplex with 3′-ssDNA tail | CTC TGC TCG ACG - Fa |

| H - CGT CGA GCA GAG (dTN)b | |

| 16-bp duplex with 3′-ssDNA tail | CTC TGC TCG ACG GAT T - F |

| H - AAT CCG TCG AGC AGA G (dTN) | |

| 20-bp duplex with 3′-ssDNA tail | TTT GGC GAC GGC AGC GAG GC - F |

| H - GCC TCG CTG CCG TCG CCA AA (dTN) | |

| 24-bp duplex with 50-nt 3′-ssDNA tail | TTC GTT TGG CGA CGG CAG CGA GGC - F |

| H - GCC TCG CTG CCG TCG CCA AAC GAA (dT50) |

aF, fluorescein.

bH, hexachlorofluorescein.

Single-stranded oligonucleotides, with or without labels, were purchased from the Shanghai Sangon Biological Engineering Technology & Services Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China), and all the synthetic oligonucleotides were purified by high-performance liquid chromatography before storage in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 1 mM EDTA at −20°C. Concentrations of single- stranded oligodeoxynucleotides were determined spectrophotometrically based on extinction coefficients calculated by the nearest-neighbour method. A 50 μM working stock of dsDNA was prepared by mixing equal concentrations of complementary single-stranded oligonucleotides in a 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0 at 25°C) containing 100 mM NaCl, followed by heating to 90°C. After equilibrating for 3 min, annealing was allowed by slow cooling to room temperature. The duplex was stored at −20°C.

Fluorometric titration assay

The binding of PcrA to ssDNA was analysed by intrinsic fluorescence measurements as described previously (39). The assays were performed using a Bio-logic auto-titrator (TCU-250) and a Bio-Logic optical system (MOS450/AF-CD). Varying amounts of ssDNA substrate were added to 1 ml of binding buffer containing 50 nM PcrA. The intrinsic protein fluorescence was measured by exciting the sample at 280 nm (0.5 nm slit width) and reading the emission at 340 nm, using a high pass filter with 40 nm bandwidth (D340/40, Chroma). Each sample was allowed to equilibrate in solution for 1.5 min, after which the fluorescence was measured. Titrations were performed in a temperature-controlled cuvette at 25°C. The solution was stirred continuously by a small magnetic stir bar during the whole titration process. Fluorescence values were corrected for inner filter effect using the absorbance at the excitation wavelength measured simultaneously during the titration.

The stoichiometry (N) and dissociation constant (Kd, in unit of molarity) were determined by fitting the fluorescence data according to Equations (1) and (2),

| 1 |

where Fc represents the corrected fluorescence, fP is the fluorescence coefficient of free PcrA, fPb is the fluorescence coefficient of PcrA bound to ssDNA, Pt is the initial total PcrA concentration, and Pb is the concentration of PcrA bound to ssDNA. cV = V0/(V0 + Vi) ≡ 1 − Dt/Dttitrant is used to accurately account for the decrease of the total PcrA concentration during the titration (i.e. the dilution effect), where V0 is the initial sample volume, Vi is the volume of titrant added, Dt is the total ssDNA concentration in the binding solution, and Dttitrant is the ssDNA concentration in the titrant.

The concentration of PcrA bound to ssDNA is given as follows,

| 2 |

where NDt is the concentration of the total binding sites of ssDNA for PcrA.

Stopped-flow kinetics measurements

All the stopped-flow kinetics assays were carried out using a Bio-logic SFM-400 mixer with a 1.5 mm × 1.5 mm cell (FC-15, Bio-Logic) and a Bio-Logic MOS450/AF-CD optical system equipped with a 150-W mercury-xenon lamp, as described previously (20).

In the DNA unwinding assays, the DNA substrates used were labelled with fluorescein (F) and hexachlorofluorescein (H), respectively, on the two strands (Table 1). Before DNA unwinding, the two fluorescent molecules are in close proximity and the emission of fluorescein is low due to FRET between the two molecules. Upon initiation of unwinding, the fluorescein emission will be enhanced due to the disruption of FRET as the two molecules are separated. Thus the change of fluorescein emission was monitored to observe the unwinding process (12).

In the unwinding assays, fluorescein was excited at 492 nm (2 nm slit width) and its emission was monitored at 525 nm using a high pass filter with 20 nm bandwidth (D525/20, Chroma). Single-turnover unwinding kinetics were measured in a two-syringe mode, where the PcrA helicase and duplex DNA substrates were pre-incubated at 25°C in syringe 1 for 5 min while ATP and protein trap in syringe 4. Each syringe contained unwinding reaction buffer and the unwinding reaction was initiated by rapid mixing of the two syringes. All concentrations listed are after mixing unless noted otherwise. We found that a small fluorescence change (∼1%) could still be observed even at extremely low ATP concentration or in the absence of ATP in control experiments. Accordingly, the background fluorescence changes were measured and subtracted from all the unwinding kinetics data. For converting the output data from volts to unwinding fraction, calibration experiments were performed in a three-syringe mode, where helicase and H-labelled ss oligonucleotide were pre-incubated in syringe 1, F-labelled ss oligonucleotide was in syringe 2, all incubated in unwinding reaction buffer, and the solution in syringe 4 being the same as in the above unwinding experiment. The fluorescent signal of the mixed solution from the three syringes corresponds to 100% unwinding.

Multiple-turnover unwinding kinetics was measured in the same way as the single-turnover unwinding kinetics. The only difference was that no protein trap was used.

For multiple-turnover unwinding kinetics in the direct-mixing experiments, i.e. no pre-incubation of PcrA with DNA substrate, PcrA was in syringe 1 while the duplex DNA substrate and ATP were pre-incubated at 25°C in syringe 4. The unwinding reaction was initiated by rapid mixing of the two syringes.

For the DNA binding kinetics assay, the PcrA helicase was in syringe 1 while the duplex DNA substrate and ATP were pre-incubated at 25°C in syringe 4. The DNA binding reaction was initiated by rapid mixing of the two syringes. The intrinsic fluorescence of PcrA at 340 nm was measured in the same way as in the fluorometric titration assay.

Kinetic data analysis

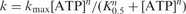

The single-turnover kinetic traces in the unwinding experiments were analysed using Bio-Kine (version 4.26, Bio-Logic) with Equation (3) (33,40),

|

3 |

where A is the unwinding amplitude, n is the number of steps, kobs = ku + kd is the observed rate constant for each step of DNA unwinding with ku being the net rate constant and kd the dissociation rate in each step.

RESULTS

Determination of the ssDNA binding stoichiometry

It has been known that the unwinding of duplex DNA by the PcrA helicase requires a 3′-ssDNA overhang (27,29). The number of PcrA molecules that bind to a given 3′-ssDNA tail depends on their binding affinity and binding site size. This information is useful for the kinetics analyses of the DNA unwinding behaviours of PcrA. We had observed that the intrinsic fluorescence of PcrA was quenched upon binding to nucleic acids. This property was used to determine the PcrA-ssDNA binding parameters, i.e. the equilibrium dissociation constant (Kd) and the stoichiometry, in a way similar to that for HCV NS3h helicase (39). The titration experiments were performed under the same buffer conditions as for DNA unwinding, but without ATP addition, by continuously titrating 50 nM PcrA (initial concentration) with increasing concentration of ssDNA. The sample was excited at 280 nm, and the intrinsic fluorescence emission at 340 nm was measured. The fluorometric data were fitted to Equations (1) and (2) to determine the stoichiometry N and the dissociation constant Kd (Materials and Methods).

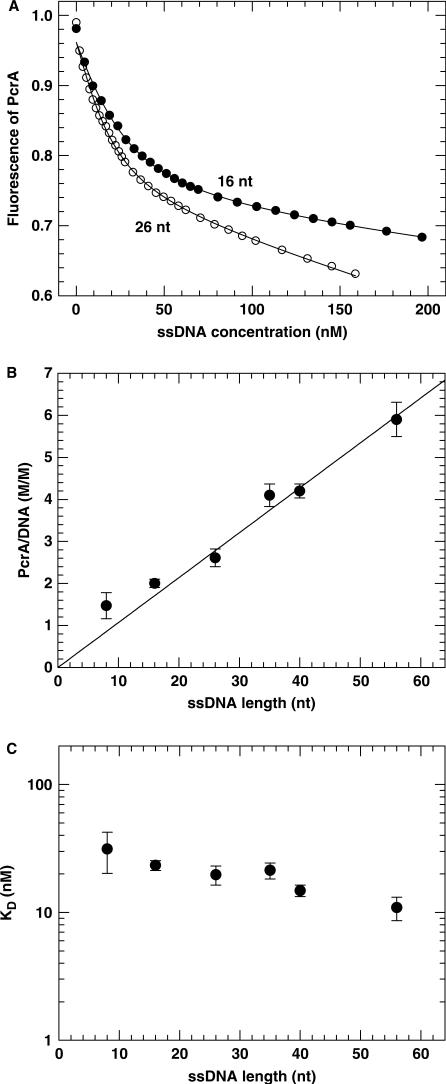

Two typical titration curves are given in Figure 1A. The initial slope of the titration curves was a function of Kd and the number of PcrA molecules bound to one ssDNA (N). At high ssDNA concentration, almost all the PcrA molecules were bound to DNA and the slower linear decrease was simply due to the dilution effect from the increasing total volume of the solution. From analyses of the binding curves for different DNA substrates with Equations (1) and (2), the stoichiometry and dissociation constant were determined. The number of PcrA molecules bound per DNA substrate increased with increasing ssDNA length (Figure 1B). A linear fit of the data for substrates longer than 16 nt gave a slope of 0.107 ± 0.003 PcrA molecule/nt, corresponding to a binding site size of 9.3 ± 0.3 nt. This value is similar to that determined for NS3h (8 nt; 39), RecQ (8−11 nt; 20,41), UvrD (11 ± 1 nt; 36; 10 ± 2 nt; 42).

Figure 1.

PcrA binding to ssDNA substrates of different lengths measured with the fluorometric titration assay. A 50 nM PcrA was titrated with ssDNA and its intrinsic fluorescence was monitored as described in the Materials and Methods. (A) Intrinsic fluorescence of PcrA as a function of ssDNA concentration for the 16- and 26-nt ssDNA substrates. The ssDNA concentration of the titrant was 2380 nM (16 nt) or 950 nM (26 nt). The solid lines represented the best fits of the data to Equations (1) and (2) with Kd = 23.3 ± 2.1 nM, N = 2.0 ± 0.1 and Kd = 19.7 ± 3.3 nM, N = 2.6 ± 0.2 for the 16- and 26-nt substrates, respectively. (B) Stoichiometry of PcrA binding as a function of the ssDNA substrate length as obtained from analyses of the titration curves. The straight line was a linear fit of the data for ssDNA substrates longer than 16 nt, giving a slope of 0.107 ± 0.003 molecule/nt and thus a binding site size of 9.3 ± 0.3 nt. (C) The determined dissociation constant per site, Kd.

For the two short substrates (8 and 16 nt), the deviation of the binding stoichiometry from the fitted line should be due to the fact that two PcrA molecules may bind to the two ends of the short ssDNA substrates though the ssDNA length available for each PcrA molecule was somewhat shorter than the binding site size. This end effect, which has also been observed for NS3h (39), can be neglected with longer substrates. The dissociation constant, Kd, is given in Figure 1C. It decreased with increasing ssDNA length.

Single-turnover kinetics study of unwinding with DNA substrates of different 3′-ssDNA tail lengths

Single-turnover kinetics study has been shown to be a powerful method for investigating the oligomerization states of helicases in DNA unwinding, where DNA substrates with different tail lengths were often used. At saturating helicase concentration, the number of helicase molecules bound to the ssDNA tail is in proportion to the tail length. Thus for DNA substrates with short tail lengths, only one helicase molecule binds to the ssDNA tail of each substrate, whereas for those with long tail lengths, more than one helicase molecule bind to the ssDNA tail. If a helicase functions as a processive monomer, it should be capable of unwinding all of the different substrates with similar unwinding rates and/or amplitudes, regardless of the tail length. Otherwise, if an oligomerization is required for the helicase function, the unwinding rate and/or amplitude should be dependent on the tail length. This method has been successfully applied to investigation of the active forms of different helicases such as UvrD (33,34) and NS3h (21). Recently, based on this method as well as pre-steady-state kinetic analyses, we have shown that RecQ is a monomeric helicase (20).

Here we used the same approach to examine the functional state of the PcrA helicase by using 16-bp duplex DNA substrates with 3′-tails of 5, 10, 15, 20, 30, 40 and 50 nt. As the ssDNA binding site size of PcrA was determined to be ∼9 nt (Figure 1), we know that only one PcrA molecule can bind to the 5- and 10-nt tailed substrates while more than one molecule may bind to the other substrates.

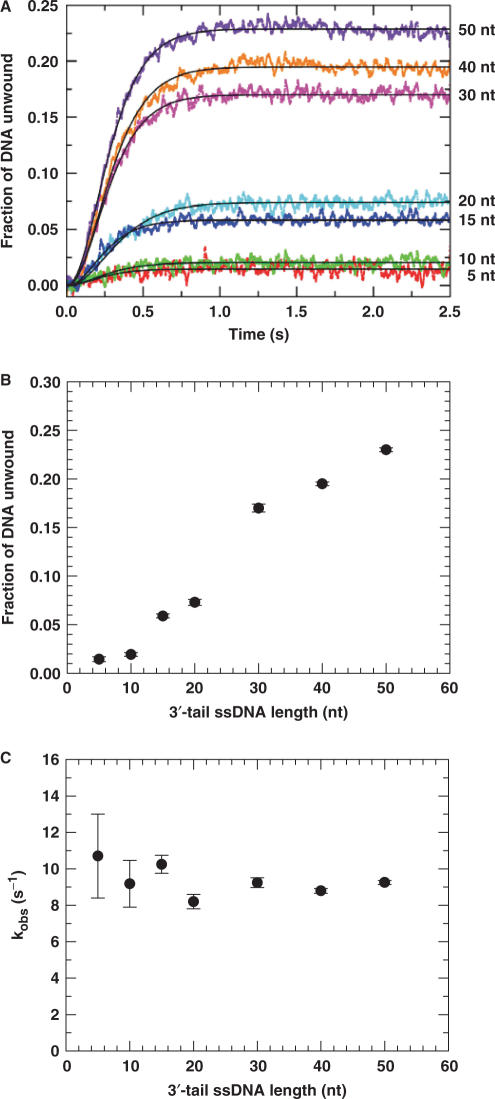

The DNA unwinding process was observed by monitoring the emission change of fluorescein labelled to the DNA substrate (Materials and Methods). We observed unwinding for all of the DNA substrates (Figure 2A). For the two DNA substrates with short tails (5 and 10 nt), the PcrA-catalysed unwinding was very low (<2%). The kinetics of unwinding could be fitted well to Equation (3) using n = 3. The amplitude increased significantly with increasing tail length (Figure 2B), similar to that for UvrD (33). The strong dependence of unwinding efficiency on the tail length indicated that PcrA oligomerization was required for efficient unwinding of the 16-bp duplex DNA substrates. This was in contrast with the case of, for example, the monomeric RecQ, where the unwinding efficiency was only slightly dependent on the tail length (20).

Figure 2.

Single-turnover DNA unwinding kinetics for 16-bp duplex DNA substrates of different 3′-ssDNA tail lengths. A 5 nM DNA substrate was first pre-incubated with excess PcrA helicase (200 nM) in the reaction buffer at 25°C for 5 min as described in the Materials and Methods. The unwinding reaction was initiated by adding 1 mM ATP and excessive protein trap (dT56, 2 μM) which prevents, after initiation, any free or dissociated PcrA molecules from rebinding to the duplex DNA substrates. The fluorescence enhancement of fluorescein due to the PcrA-catalysed strand separation was observed continuously. The amount of DNA unwound was determined by the calibration method as described in the Materials and Methods. (A) The kinetic time-courses for different substrates. The solid lines shown were the best fits of the data to Equation (3) with n=3. (B) Unwinding amplitude. (C) The observed rate constant for each unwinding step.

The observed unwinding rate for each unwinding step is essentially independent of the tail length (Figure 2C) with an average value of 9.4 ± 0.8 s−1.

Multiple-turnover kinetics of DNA unwinding with substrates of different 3′-ssDNA tail lengths

The above study clearly indicates that the PcrA helicase functions much better as oligomers than as monomers. But as the experiments were performed under single-turnover conditions, the negligible unwinding of short-tailed DNA substrates may be due to the premature dissociation of the bound monomers rather than their low helicase activity or inactivity. In the case of the monomeric NS3h or Dda helicases (21,43), for example, the DNA unwinding efficiency depends on the substrate tail length because the helicase dissociates easily from the substrates during unwinding. Thus we next carried out multiple-turnover kinetics assays while still using the same substrates as before. In the absence of protein trap, PcrA molecules can bind to DNA rapidly as long as new binding sites become available with the dissociation of the bound monomers during unwinding. Thus if the PcrA helicase functions well as a monomer but only has a low processivity, we expect that the short-tailed DNA substrates would still be efficiently unwound.

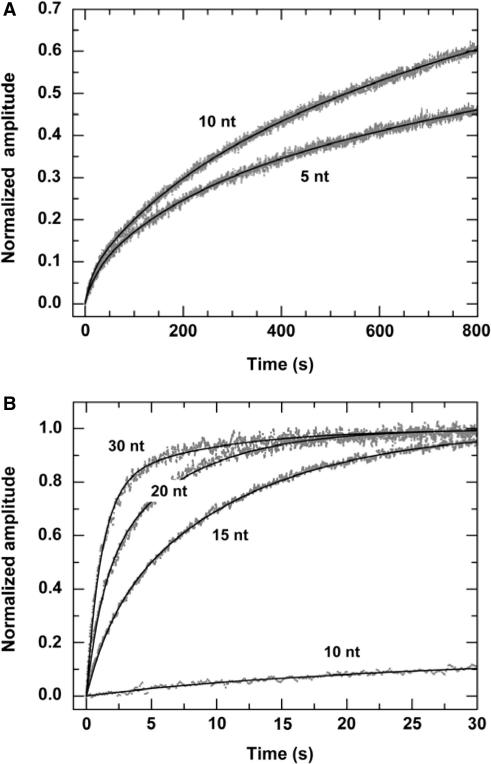

Under multiple-turnover conditions, we observed obvious unwinding for all the DNA substrates. The unwinding efficiencies, however, are quite different for the different substrates (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Multiple-turnover DNA unwinding for 16-bp duplex DNA substrates of different 3′-ssDNA tail lengths. A 2 nM DNA substrate was first pre-incubated with excess PcrA helicase (100 nM) in the reaction buffer at 25°C for 5 min and the unwinding reaction was initiated by adding 1 mM ATP. The maxima of the curves were normalized. (A) The kinetic time-courses for the 5- and 10-nt tailed substrates. The solid lines were three-exponential fits of the data. For the 5-nt substrate the obtained parameters are Afast=0.06 ± 0.01, Aslow,1=0.20 ± 0.01, Aslow,2=0.74 ± 0.01 and kfast=0.041 ± 0.005 s−1, kslow,1=(4.9 ± 0.4)×10−3 s−1, kslow,2=(3.9 ± 0.2)×10−4 s−1. For the 10-nt substrate the obtained parameters are Afast=0.06 ± 0.01, Aslow,1=0.16 ± 0.01, Aslow,2=0.78 ± 0.01 and kfast=0.074 ± 0.007 s−1, kslow,1=(6.1 ± 0.3)×10−3 s−1, kslow,2=(8.5 ± 0.1)×10−4 s−1. (B) The kinetic time-courses for the 15-, 20- and 30-nt substrates. The solid lines were double-exponential fits of the data. The time-course for the 10-nt substrate was also given for comparison.

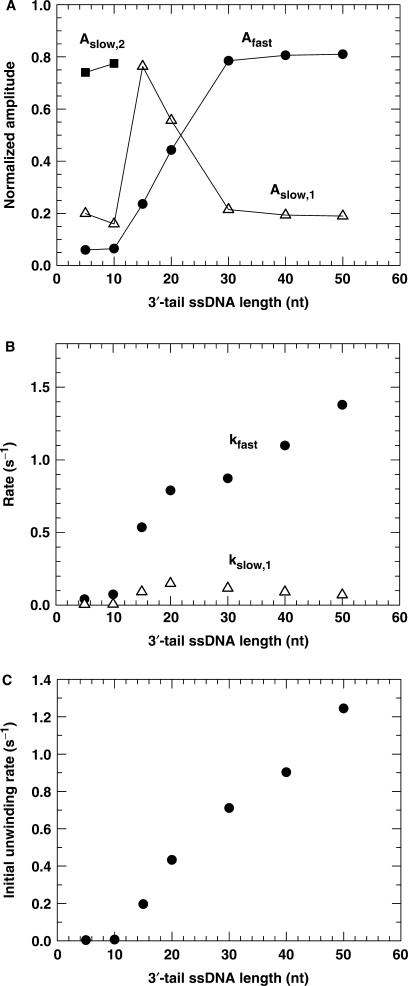

We found that the unwinding kinetics were triphasic for the 5- and 10-nt tailed substrates and biphasic for the others. The unwinding amplitudes obtained from the fitting are given in Figure 4A. The amplitude for the fast phase is low at the two short tail lengths. It increases significantly with increasing tail length and saturates at 30 nt.

Figure 4.

The kinetic parameters for PcrA-catalysed DNA unwinding under multiple-turnover condition for 16-bp duplex DNA substrates of different 3′-ssDNA tail lengths, obtained from analyses of the time-courses in Figure 3. (A) Amplitudes. (B) Rates of the fast phase and slow phase. Here the rate for the second slow phase in the case of the 5- and 10-nt tailed substrates was not presented. (C) The initial unwinding rate.

The observed unwinding rates were plotted as a function of the tail length in Figure 4B. The rates of the first two phases for the 5- and 10-nt tailed substrates are significantly lower than the corresponding ones for the other long-tailed ones. For example, the rate for the fast phase at 10 nt is 7.3 times lower than that at 15 nt. The rate for the fast phase increases with the tail length.

The initial unwinding rates for the 5- and 10-nt tailed substrates are also significantly smaller than that for the other long-tailed substrates (Figure 4C). The value for the 10 nt DNA, 0.0063 s−1, is ∼30 times smaller than that for the 15 nt DNA, 0.197 s−1. For the 15−50 nt DNA substrates, the initial unwinding rate increases almost linearly with the ssDNA tail length.

The above results have clearly shown that the unwinding of the 5- and 10-nt tailed substrates is in significant difference with that of the longer-tailed substrates. This cannot be explained if PcrA functions as a low-processivity monomer because the binding rate of PcrA to the newly vacated ssDNA should not be so variant for the ⩽10 nt and ⩾15 nt tails (Figure 1C). Rather, it suggests that the PcrA monomers bound to the short-tailed substrates are not capable of initiating the DNA unwinding and PcrA oligomerization is required for efficient unwinding.

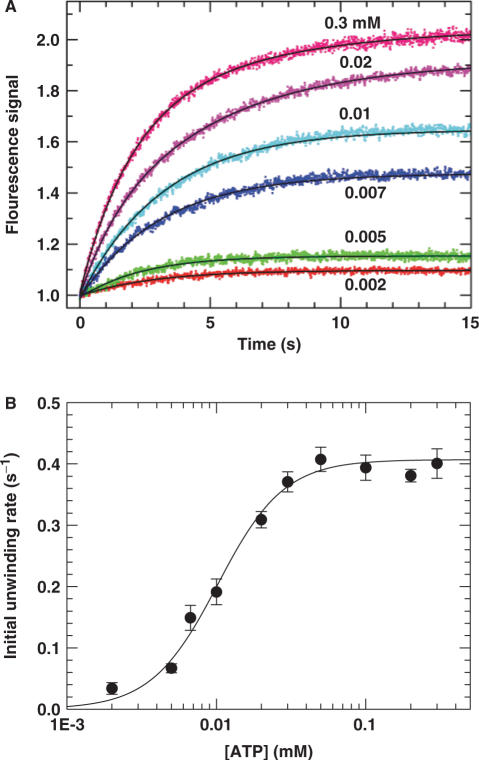

Effect of ATP concentration on the multiple-turnover kinetics of DNA unwinding

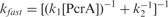

The above studies indicate that the PcrA helicase functions much better as oligomers than as monomers. In addition, as the unwinding efficiency becomes enhanced as long as the DNA tail is long enough for the binding of another monomer, it is very probable that the active form of PcrA is a dimer. To verify this, we performed a DNA unwinding kinetics assay with varying [ATP] using 20-nt-tailed 16-bp DNA substrate. Originally, we intended to carry out the experiments under single-turnover conditions, but found that the ATP became depleted rapidly at low ATP concentrations due to the large amount of trapped PcrA molecules that were consuming ATP by translocating along the protein trap, dT56. Under multiple-turnover conditions, there was no such a problem because there was no protein trap and the ATP was only consumed by the PcrA molecules for the unwinding of DNA just after initiation.

The fluorescence stopped-flow experiments were performed by pre-incubating 5 nM DNA with 200 nM PcrA for 5 min. The unwinding reaction was initiated by addition of ATP with a concentration ranging from 0.002 to 0.3 mM. Some typical unwinding time-courses are given in Figure 5A. By exponential fitting of the experimental curves, the [ATP] dependence of the initial unwinding rate was obtained (Figure 5B). We found the dependence could be well described by the Hill equation. The Hill coefficient, which provides an estimate of the minimum number of interacting ATP-binding sites involved in the unwinding reaction, is 1.9 ± 0.3. This value is consistent with PcrA helicase utilizing two interacting ATP-binding sites in the course of DNA unwinding. Since each PcrA helicase monomer contains a single ATP binding/hydrolysis site (27,28), these data suggest that the functional oligomer of PcrA helicase is composed of two monomers.

Figure 5.

Dependence of DNA unwinding on [ATP] under multiple-turnover conditions. A 5 nM 20-nt-tailed 16-bp duplex DNA was first pre-incubated with excess PcrA helicase (200 nM) in the reaction buffer at 25°C and the unwinding reaction was initiated by adding ATP. (A) Typical kinetic time-courses at different [ATP]. The solid lines were exponential fits of the data. (B) The initial unwinding rate. The line corresponded to a fit of the data to the Hill equation  , where n is the Hill coefficient. The fitted values were K0.5=10.2 ± 0.8 μM and n=1.9 ± 0.3.

, where n is the Hill coefficient. The fitted values were K0.5=10.2 ± 0.8 μM and n=1.9 ± 0.3.

It should be noted that in the above experiment, the number of binding sites available for PcrA molecules on the DNA substrate was just two. Thus it is possible that the determined Hill coefficient of ∼2 may be a result of the specific substrate used. To clarify this issue, we repeated the same experiment while using a 30-nt-tailed DNA substrate. From the measured ssDNA binding site size of ∼9 nt, it is expected that at least three PcrA molecules can bind to the ssDNA tail of the substrate. With this new substrate, the fitted Hill coefficient, 1.8 ± 0.3, is quite similar to that obtained with the 20-nt-tailed substrate (Fig. S2, Supplementary Data). Therefore, we may conclude that the observed [ATP] dependence of the DNA unwinding rate is intrinsic to the helicase activity of PcrA.

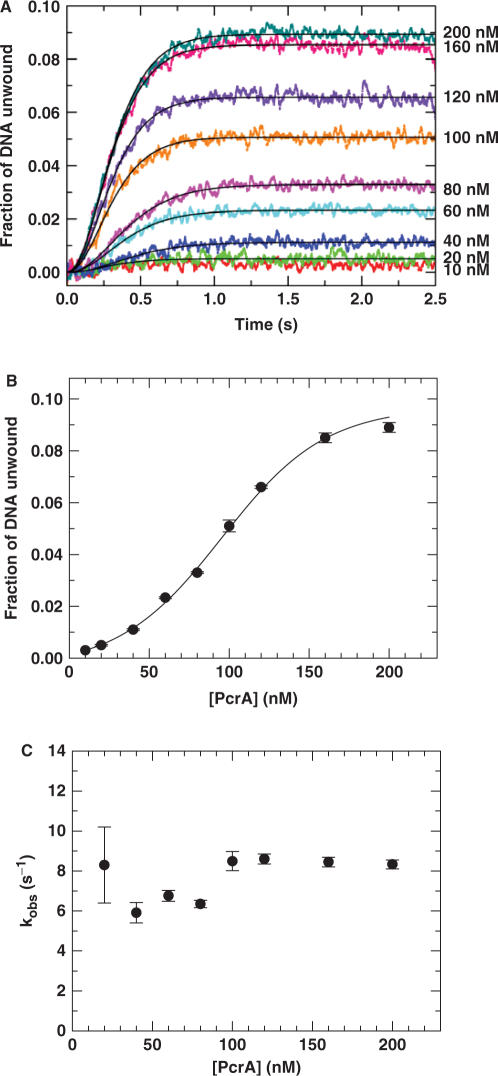

Single-turnover unwinding kinetics with varying PcrA concentration

In all the previous kinetics studies, an excess of PcrA protein was pre-incubated with a low concentration DNA substrate (2 or 5 nM). To examine the dependence of DNA unwinding on [PcrA] in more detail, we have performed single-turnover DNA unwinding experiments at a higher DNA concentration while [PcrA] ranged from well below to well above the DNA concentration. We used 20-nt-tailed 16-bp duplex as the substrate. Under conditions where PcrA protein is in large excess over the DNA substrate, protein dimerization will be favoured. However, the binding of PcrA monomer will be favoured when [PcrA] is below the DNA concentration.

In these unwinding experiments, we used a concentration of 20 nM for the DNA substrate while [PcrA] was over the range of 10−200 nM. The measured time courses are shown in Figure 6A. They could be fitted well to Equation (3) using n = 3, except for the case of 10 nM at which the unwinding efficiency was negligibly low. The obtained unwinding amplitude had a sigmoidal dependence on [PcrA] (Figure 6B), supporting further that PcrA functions as a dimer. Similar curves have been observed for Rep (13) and UvrD (33). The observed rate constant for each unwinding step, kobs, is essentially independent of [PcrA] (Figure 6C). This indicates that these are single-turnover conditions with respect to the DNA substrate and that the PcrA molecules bound in a productive complex to the DNA substrate is the same at each PcrA concentration.

Figure 6.

Single-turnover kinetics of DNA unwinding with different PcrA concentrations. A 20 nM 20-nt-tailed 16-bp duplex substrate was first pre-incubated with PcrA at the indicated concentrations in the reaction buffer at 25°C and the unwinding reaction was initiated by adding 1 mM ATP and excessive protein trap (dT56, 2 μM). (A) Kinetic time-courses. The solid lines shown were the best fits of the data to Equation (3) with n=3. (B) Amplitude of unwinding as a function of [PcrA]. The solid line represented a sigmoidal fit of the data. (C) The observed rate constant for each step of DNA unwinding.

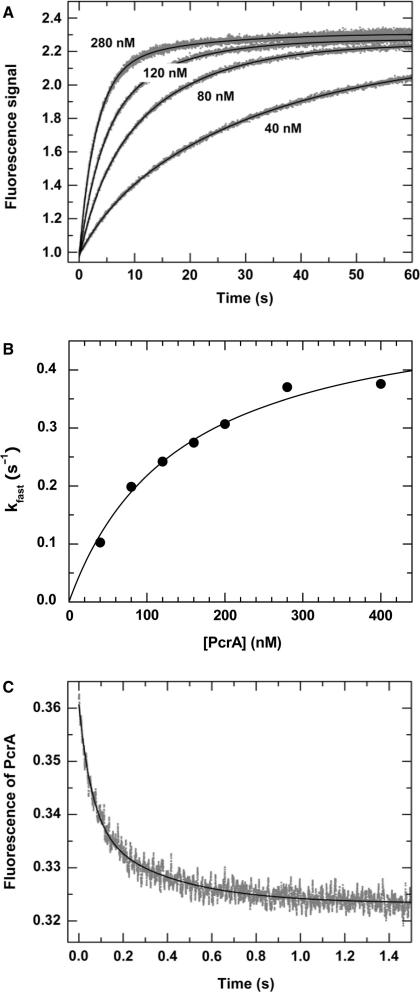

Multiple-turnover kinetics of DNA unwinding when PcrA was not pre-incubated with DNA

The DNA unwinding experiments described before were performed by pre-incubating PcrA with the DNA substrates and initiating unwinding by addition of ATP. To further examine whether a PcrA monomer can initiate DNA unwinding, we studied the multiple-turnover kinetics of DNA unwinding initiated by direct mixing of PcrA with the DNA substrate in the presence of ATP, as performed previously for the Rep helicase by Cheng et al. (13). If PcrA monomers are capable of initiating DNA unwinding, the dependence of the unwinding rate on [PcrA] should only be determined by DNA binding of PcrA monomers. Otherwise, it would be determined by both DNA binding and protein assembly of PcrA.

For these direct-mixing experiments, we still used the 20-nt tailed substrate to which two PcrA molecules may bind. Typical fluorescence time courses are shown in Figure 7A. From double-exponential fits of the curves, we obtained the rate constant for the fast phase, kfast, as a function of [PcrA] (Figure 7B). kfast displays a roughly hyperbolic dependence on [PcrA]. This fast phase is composed of two reactions: one is [PcrA]-dependent with a second-order rate constant k1, and the other is independent of [PcrA] with a first-order rate constant k2. From the fitting of the data, we obtain k1=(3.7 ± 0.3)×106 M−1 s−1, which corresponds to the PcrA binding and/or assembly, and k2 = 0.53 ± 0.03 s−1, which corresponds to DNA unwinding and other [PcrA]-independent processes.

Figure 7.

Kinetics for multiple-turnover DNA unwinding and for DNA binding by direct mixing. In the multiple-turnover unwinding kinetics measurements, a 5 nM 20-nt-tailed 16-bp duplex DNA was first pre-incubated with 1 mM ATP and the reaction was initiated by adding PcrA at the indicated concentrations as described in the Materials and Methods. In the DNA binding measurement, a 5 nM 20-nt-tailed 16-bp duplex DNA was first pre-incubated with 1 mM ATP and the reaction was initiated by adding 120 nM PcrA. The intrinsic fluorescence of PcrA was monitored as described in the Materials and Methods. (A) Typical kinetic time-courses at different [PcrA]. The solid lines were double-exponential fits of the data. (B) The observed rate for the fast phase, obtained from fits of the unwinding curves, as a function of [PcrA]. The line corresponds to a fit of the data to the equation  , where k1 is the second-order rate constant for the reaction of PcrA binding and/or assembly, k2 is the first-order rate constant for the other PcrA-concentration-independent processes. The fitted values are k1=(3.7 ± 0.3)×106 M−1 s−1 and k2=0.53 ± 0.03 s−1. (C) Kinetics of PcrA monomer binding to DNA. The line was a double-exponential fit, giving the observed rate constants for the fast and slow phases as 16.7 ± 0.4 and 2.8 ± 0.1 s−1, respectively.

, where k1 is the second-order rate constant for the reaction of PcrA binding and/or assembly, k2 is the first-order rate constant for the other PcrA-concentration-independent processes. The fitted values are k1=(3.7 ± 0.3)×106 M−1 s−1 and k2=0.53 ± 0.03 s−1. (C) Kinetics of PcrA monomer binding to DNA. The line was a double-exponential fit, giving the observed rate constants for the fast and slow phases as 16.7 ± 0.4 and 2.8 ± 0.1 s−1, respectively.

The above [PcrA]-dependent reaction corresponds either to PcrA binding alone or to both PcrA binding and assembly. To discriminate between them, the kinetics of PcrA monomer binding was examined using the same 20-nt tailed substrate as before. Figure 7C shows the fluorescence time course at 120 nM [PcrA]. It could be described by a sum of two exponential phases with rate constants of 16.7 ± 0.4 and 2.8 ± 0.1 s−1, respectively. The fast phase corresponds to the intrinsic fluorescence change of PcrA upon initial binding to DNA while the slow phase should correspond to further conformational change after binding to DNA (30,44). The above rate constant for the fast phase ([PcrA]-dependent) is about 40 times higher than the rate of the [PcrA]-dependent reaction obtained in the direct-mixing unwinding experiments at the same [PcrA] of 120 nM, k1 × 120 nM=0.44 s−1. This indicates that, after the rapid initial binding to DNA, PcrA assembly is required prior to the initiation of DNA unwinding, similar to that as observed for Rep (13). It should be mentioned that, based on fluorescence enhancement of 2-aminopurine-substituted DNA by PcrA binding, Dillingham et al. (44) had obtained a saturating rate of 35 s−1 for PcrA binding to ssDNA in the absence of ATP, which is comparable to that we obtained here (16.7 s−1).

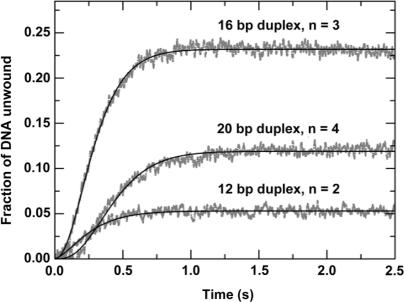

Step-size determination

Helicases couple NTP hydrolysis to mechanical movements and unwind duplex DNA or RNA through multiple steps. The step size is an important parameter for characterizing the unwinding behaviours of a helicase and is essential for the understanding of its unwinding mechanism. Here we determined the step size of PcrA with a series of 50-nt-tailed ss/dsDNA varying in duplex length from 12 to 24 bp. The experiments were performed under single-turnover conditions as that in Figure 2.

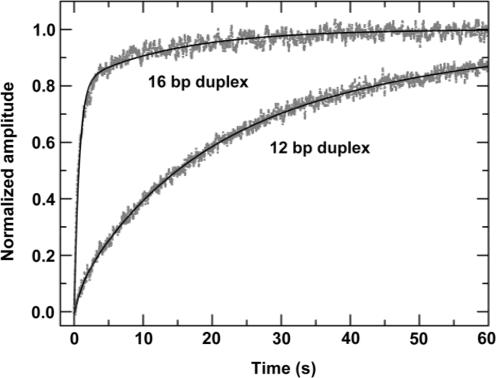

We have observed that the unwinding amplitude varied significantly for different substrates. The unwinding curves for the 12-, 16- and 20-bp duplex substrates are given in Figure 8. The unwinding amplitude for the 20-bp substrate is lower than that for the 16-bp substrate. For the 24-bp substrate, the amplitude is very low (<2%, data not shown). This decrease of amplitude with increasing duplex length can be easily understood because the PcrA molecules may dissociate during unwinding, as was also observed for Rep (14,40). What is surprising is that the unwinding amplitude for the 12-bp substrate is not higher, but rather, much lower than that for the 16-bp substrate, an unusual behaviour to be studied further in the following.

Figure 8.

Single-turnover kinetics of DNA unwinding for 50-nt-tailed ss/dsDNA substrates of different duplex lengths. A 5 nM 50-nt-3′-tailed ss/dsDNA substrate was first pre-incubated with 200 nM PcrA helicase for 5 min, the reaction was then initiated by rapid addition of 1 mM ATP and excessive protein trap (dT56, 2 μM). The lines represented the best fits of the data to Equation (3) with n = 2, 3, 4; A=0.053 ± 0.001, 0.232 ± 0.002, 0.119 ± 0.001; kobs=6.9 ± 0.2, 9.2 ± 0.1, 8.4 ± 0.1 s−1 for the 12-, 16-, and 20-bp duplex substrates, respectively.

Fitting the data in Figure 8 to Equation (3), the number of steps and the observed rate for each step were obtained. The step numbers are 2, 3 and 4 and the rates are 6.9 ± 0.2, 9.2 ± 0.1 and 8.4 ± 0.1 s−1, respectively, for the 12-, 16- and 20-bp duplex substrates. By a linear fit of the data for the step numbers at different duplex lengths, a DNA unwinding step size of 4 bp was obtained. As the average rate for each step is 8.2 ± 1.2 s−1, the macroscopic DNA unwinding rate is 33 ± 5 bp s−1.

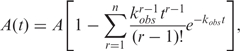

Multiple-turnover kinetics of DNA unwinding for 12-bp duplex DNA

In the previous single-turnover experiments, the unwinding amplitude for the 12-bp DNA substrate was much lower than that for the 16-bp substrate. This is unexpected because DNA unwinding efficiency is always more efficient for a short duplex substrate than for a long one. To further verify the result, we examined the DNA unwinding behaviours for the 50-nt-tailed 12-bp duplex DNA under multiple-turnover conditions. The result is given in Figure 9 together with that for the 50-nt-tailed 16-bp DNA for comparison. It was found that the unwinding kinetics curve for the 12-bp substrate was composed of three phases. That is, an additional slow phase appeared. The rates of the first two phases for the 12-bp substrate, 0.93 ± 0.22 s−1 and 0.068 ± 0.004 s−1, are similar to that of the two phases for the 16-bp substrate, 1.38 ± 0.04 s−1 and 0.071 ± 0.003 s−1. However, the amplitude of the fast phase for the 12-bp substrate, 0.07 ± 0.01, is much lower than that for the 16-bp substrate, 0.81 ± 0.02, indicating that the fast phase is significantly influenced with the short-duplex DNA.

Figure 9.

Multiple-turnover DNA unwinding kinetics for the 50-nt-tailed 12-bp duplex DNA substrate. The experiment was carried out under the same conditions as for the 16-bp DNA (Figure 3). The previous result for the 16-bp DNA substrate was also given here for comparison. For the 12-bp substrate, the solid line was a three-exponential fit with Afast=0.07 ± 0.01, Aslow,1=0.49 ± 0.03, Aslow,2=0.44 ± 0.03 and kfast=0.93 ± 0.22 s−1, kslow,1=0.068 ± 0.004 s−1, kslow,2=0.021 ± 0.001 s−1. For the 16-bp substrate, the solid line was a double-exponential fit with Afast=0.81 ± 0.02, Aslow=0.19 ± 0.01 and kfast=1.38 ± 0.04 s−1, kslow=0.071 ± 0.003 s−1.

Similarly, we have examined the DNA unwinding behaviours for the 10-nt-tailed 12-bp duplex DNA under multiple-turnover conditions. The unwinding is also slower than that for the 10-nt-tailed 16-bp DNA (data not shown).

Thus both single- and multiple- turnover experiments showed that the unwinding for the 12-bp duplex DNA was much less efficient than for the 16-bp substrates. As will be discussed later, the unusual results are relevant to the DNA unwinding mechanism of PcrA and may be explained by considering the interaction of PcrA with the duplex portion of the DNA substrates.

DISCUSSION

The main active form of PcrA is a dimer

In the single-turnover kinetics studies with substrates of different tail lengths, the unwinding amplitude is low for the 5- and 10-nt substrates and then increases significantly for substrates with tails long enough to load two or more PcrA molecules (Figure 2). The results clearly indicate that the PcrA helicase functions much better as oligomers than as monomers. As these experiments were performed under single-turnover conditions, the negligible unwinding of the short-tailed substrates may also be explained by assuming that PcrA is a monomeric helicase and the PcrA monomers prematurely dissociate from the substrates before finishing the unwinding. However, this is not supported by dissociation experiments showing that, after the initiation of unwinding, PcrA molecules are dissociated from the 10-nt substrate with a rate of 0.3 s−1 (Fig. S3, Supplementary Data). This dissociation rate is much lower than the macroscopic rate (∼3 s−1) for unwinding a 16-bp duplex in three steps with an unwinding rate of ∼9 s−1 for each step (Figure 2C), indicating that the PcrA monomers remained bound to the substrates but did not catalyse the unwinding.

The above observed effect of tail length on the DNA unwinding efficiency is similar to that observed for the dimeric UvrD (33,34). That is, the unwinding efficiency is negligible as long as the tail length is only large enough (∼10 nt) to load one helicase monomer and then becomes obvious when the tail is long enough (⩾ ∼14 nt) to load a second monomer. This is in contrast with the cases of monomeric helicases, such as NS3h (21), RecQ (20) and Dda (43), where the unwinding efficiency might also decrease with decreasing tail length, but the unwinding amplitude is already significant at 5- or 6-nt tail length. For these monomeric helicases, the variation of unwinding efficiency at tail lengths below ∼10 nt is simply caused by the varying binding affinity of a helicase monomer for the short ssDNA tail.

The above evidence for the functioning of PcrA as oligomers is further supported by the multiple-turnover kinetics studies where the unwinding amplitude and rate for the fast phase as well as the initial unwinding rate are negligibly low for the 5- and 10-nt substrates and then increases dramatically for substrates with longer tails (Figure 4). As at most two PcrA molecules can bind to the 15-nt substrate, the abrupt changes at the 15-nt tail length suggest more definitely that the active form of PcrA is a dimer. Note that, in the multiple-turnover experiments, if the originally bound PcrA molecules prematurely dissociate from the substrates, the unwinding will be continued by molecules newly bound to the ssDNA tail just vacated. Thus the unwinding rate, which depends on the binding rate of PcrA molecules to the ssDNA tail, is a function of the tail length (Figure 4B). This is in contrast with the single-turnover experiments where the rate is essentially constant (Figure 2C) because in these experiments, we can only observe the DNA substrates for which the unwinding is finished by the originally bound PcrA molecules. If the originally bound PcrA molecules dissociate from the substrates before finishing the unwinding, these substrates do not contribute to the observed unwinding amplitude.

The observed effect of [ATP] on the unwinding rate (Figure 5 and Fig. S2, Supplementary Data) is a strong support of the dimeric form of PcrA. The obtained Hill coefficient (∼2) indicates that the number of interacting ATP-binding sites or PcrA molecules involved in the unwinding reaction is two.

In the single-turnover experiments with different [PcrA], the unwinding amplitude depends sigmoidally on [PcrA] (Figure 6), in a way similar to that observed for Rep (13) and UvrD (33). This result is consistent with the suggestion that the active form of PcrA is a dimer.

It should be mentioned that 20-nt-tailed ss/dsDNA substrates have been frequently used in our experiments. Some explanations of the experimental results are based on the assumption that two PcrA monomers may bind to the 20-nt tail of the substrates. To determine whether a PcrA dimer was indeed formed on a 20-nt ssDNA tail, we carried out a cross-linking experiment with the reagent DMS. PcrA alone or in the presence of ssDNA were mixed with DMS. After reaction the products were electrophoresed on an SDS–PAGE gel.

As shown in Fig. S4 (Supplementary Data), addition of DMS to PcrA alone led only to a broader band of PcrA monomers, probably due to the covalent addition of DMS molecules to PcrA monomers. In contrast, when DMS was added to the pre-incubated PcrA and ssDNA mixture, a covalent complex migrated more slowly on SDS–PAGE gels. This cross-linked product corresponds to dimers of PcrA, judged from the molecular marker. Increasing the amount of DMS resulted in proportionate increases in the band. Note that the formation of this cross-linked product was not very efficient, possibly because of the scarcity of DMS-reactive residues in the protein–protein interface of the PcrA dimer formed on ssDNA.

Taken together, the experimental results from the present kinetics studies suggest that PcrA is a dimeric helicase, rather than a monomeric one as generally believed before.

PcrA has a low processivity

To the 20-nt tailed substrate, on average only two PcrA molecules are bound before the initiation of unwinding. Under the single-turnover conditions, the fraction of DNA unwound for the 20-nt 16-bp DNA substrate is 0.073 (Figure 2B). From this result we can make a rough estimate of the processivity of a PcrA dimer, P = ku/(ku + kd) (40), which corresponds to the possibility that the helicase still remains functioning on the substrate after one unwinding step. A low processivity results in reduced unwinding amplitude.

After initiation of unwinding under single-turnover conditions, the unwinding process will be terminated if one of the two helicase molecules dissociates from the DNA substrate, as in the case of Rep (14). As three steps are required for the unwinding of the 16-bp DNA, the possibility that both of the two helicase molecules still remain bound to the substrate after the first two steps is P2. Thus we should have P2 ≅ 0.073 or P ≅ 0.27. This value is smaller than that determined for UvrD (0.9; 40). This may explain why the unwinding amplitude is still low (0.23) for the 50-nt tailed 16-bp substrate (Figure 2B), whereas it already starts to saturate at ∼30 nt for UvrD (33,34). The significant difference of the unwinding efficiencies for the 50-nt-tailed 16- and 20-bp DNA substrates (Figure 8), which was caused by only one additional unwinding step, also implies that the PcrA molecules may easily detach from DNA during each step. The above observations are consistent with previous studies showing that the DNA unwinding processivity of PcrA alone is low (26). For a 20-nt 20-bp DNA substrate, the unwinding requires four steps and the possibility that the two PcrA molecules still remain bound to the substrate after the first three steps is P3 ≅ 0.02. Actually no unwinding was observed for this substrate (data not shown).

It should be noted that, in the above estimation of P, we have not considered the possible dissociation of the PcrA molecules from the ssDNA tail or the ss/dsDNA junction after initiation of unwinding for the following two reasons. First, from the experimental results on ssDNA translocation of PcrA (44), it can be seen that the dissociation rate of PcrA during ssDNA translocation is negligible, as is also the case for UvrD (45). Second, as mentioned before, the dissociation measurement indicates that the dissociation is slow for the helicase monomers initially bound to the ss/dsDNA junctions upon initiation of unwinding.

Comparisons with the previous study of PcrA helicase

Recently Niedziela-Majka et al. (38) have studied the ssDNA translocation and dsDNA unwinding kinetics of B. stearothermophilus PcrA. They have shown that the PcrA monomers are able to translocate rapidly and processively along ss-DNA in the 3′ to 5′ direction. However, the same PcrA monomers fail to catalyse DNA unwinding. Here it is interesting to make a comparison between the previous and our present studies. In the previous study, it was observed that, under single-turnover conditions, the 20-nt 18-bp ss/dsDNA substrate could not be unwound when the PcrA concentration was well below that of the DNA substrate (20:100 or 40:120), implying that the PcrA monomers were not able to catalyse DNA unwinding (38). This result is similar to our present one as shown in Figure 6 when the PcrA concentration is below that of DNA (10:20). Furthermore, it was shown that at saturating PcrA concentrations, the 20-nt-tailed 18-bp ss/dsDNA could be unwound obviously, whereas the unwinding of a 7-nt-tailed substrate was negligible under the same single-turnover conditions (38). These results are consistent with our present ones as shown in Figure 2. Interestingly, for the 20-nt-tailed substrate, the unwinding kinetics was biphasic in the previous study (38) while we have only observed the fast phase in our experiments. This difference may probably be due to the different buffer conditions and/or different experimental methods (i.e. fluorescence stopped-flow versus quenched-flow). It may be seen that our present study complements the previous one by showing that dimer is the oligomeric state of the PcrA helicase in vitro.

Implications for the mechanism of DNA unwinding

In addition to giving support for a dimeric form of PcrA, the present study provides new clues to its DNA unwinding mechanism. First, during DNA unwinding, the second PcrA monomer remains following the first monomer along the ssDNA tail and it does not interact with the duplex DNA. This can be induced from the following facts. When the tail length is only ∼20 nt, the duplex portion of the DNA substrate is out of reach for the second monomer that binds to the end of the ssDNA tail. In addition, as DNA footprinting and cocrystal structures reveal that the maximum binding site size of PcrA and UvrD monomers for the duplex portion of a ss/dsDNA is in the range of 13−16 bp (28,31,37), it is expected that the first monomer at the ss/dsDNA junction will cover almost the whole duplex portion of the 16-bp substrates.

Secondly, the interaction of the first monomer with the duplex DNA plays a very important role in the initiation of unwinding. This can be seen from the much reduced DNA unwinding efficiency for the 12-bp DNA substrate compared with that for the 16-bp DNA substrate under both single- and multiple-turnover conditions (Figures 8 and 9). We believe these unusual phenomena result very probably from the reduced binding affinity of the first PcrA monomer for the DNA substrate that has a duplex length smaller than the maximum binding site size (13−16 bp).

Thirdly, the interaction of the first monomer with the duplex DNA seems to be less important after the unwinding initiation, i.e. during the DNA unwinding process. This is supported by the fact that the observed unwinding rates for each step were similar for the 12- and 16-bp DNA substrates (Figure 8). Furthermore, if the interaction is also very important during unwinding, then we cannot understand why the unwinding efficiency for the 16-bp substrate is much better than for the 12-bp substrate, considering that after unwinding the 16-bp substrate by one step, its duplex length will become 12 bp also.

In the case of the monomeric helicases Dda and RecQ (18,20,43), the unwinding for a 12-bp DNA is better than for a 16-bp DNA, in contrast with the present case of PcrA. This implies that, in the DNA unwinding, the interactions between the enzyme and the duplex DNA may be different and/or play different roles for dimeric and monomeric helicases. One possible reason for the differences is the different helicase tertiary structures: four domains for dimeric PcrA (28), UvrD (37) and Rep (35) versus three domains for monomeric NS3h (22), RecQ (24), or two domains for monomeric Dda (46). Interestingly, after the deletion of the 2B subdomain of Rep, the three-domain mutant (RepΔ2B) becomes a monomeric helicase and unwinds DNA more efficiently than the wild-type helicase (47,48). In addition, its unwinding efficiency for a 12-bp DNA is better than for a 18-bp DNA (48). A comparison of the amino acids sequence and crystal structure of Rep with that of RecQ indicates that the 2B-domain-deleted Rep is structurally close to RecQ (20). A similar mutational study for PcrA may be interesting in the future.

From the above discussions we can see that the interaction between the first PcrA monomer and the duplex portion of the DNA substrate plays a very important role in the DNA unwinding. This is consistent with the mutational studies showing that the duplex-binding domains are essential for DNA unwinding (31). Thus although the cocrystal structures of PcrA (28) and UvrD (37) with partial duplex DNA may not show the active forms of the helicases, they represent probably the functional states of the first monomer interacting with the ss/dsDNA junction before the initiation of unwinding and/or during the unwinding processes.

So what is the function of the second monomer in DNA unwinding? One may easily think that the first PcrA monomer is responsible for unwinding, whereas the second or the more additional monomers bound to the ssDNA tails serve to increase the unwinding processivity by replacing the dissociated monomers moving ahead, as in the cases of NS3h (21) and Dda (43). But this is not supported by the experimental results such as that for the effect of [ATP] (Figure 5 and Fig. S2, Supplementary Data) and for the assembly of PcrA monomers (Figure 7). Another possibility is that the second monomer serves to prevent reannealing of the ssDNA formed after unwinding by the first PcrA monomer. However, our previous study with RecQ has shown that the reannealing of the ssDNA behind a single RecQ molecule was only significant for 20-bp or longer duplex substrates but was negligible for a 16-bp one (20). A third possibility is that the second PcrA monomer acts as a barrier to the dissociation of the first PcrA monomer bound at the ss/dsDNA junction. In the case of UvrD, this possibility was ruled out because it has been shown that other proteins, including a mutant UvrD with no ATPase activity as well as a monomer of the structurally homologous E. coli Rep helicase, cannot substitute for the second UvrD monomer, suggesting a specific interaction between the two UvrD monomers (34). At the moment it is still difficult to clearly define the function of the second PcrA monomer. More information, such as the regulating effects of nucleotide cofactors on the ss- and dsDNA binding and assembly properties of PcrA should be required for that purpose.

Finally, it should be emphasized that SSB, which would be present on DNA substrates in vivo, is absent from our experiments. If the second monomer in the PcrA dimer is simply a placeholder that keeps an otherwise active monomer in place (i.e. at the ss/dsDNA junction), then this could be a function normally carried out by SSB in cells. Thus it remains possible that the stimulatory role of the second PcrA monomer in vitro could be substituted by SSB or other accessory proteins. The interesting subject of the effect of SSB on PcrA activity is currently investigated in our laboratories.

In summary, we have provided evidence that a dimeric PcrA is required for efficient DNA unwinding in vitro. But many questions still remain to be answered. For example, what is the exact role of the second monomer and how does it interact with the first monomer during DNA unwinding? Does the first PcrA monomer switch its unwinding mechanism (from wrench-and- inchworm to strand-displacement) when the duplex portion becomes too short (<14 bp) during unwinding, as proposed for UvrD (37)? This seems to be difficult to determine by kinetic analyses because it cannot distinguish between different types of step, if they really exist. Single-molecule studies may provide the answers by monitoring individual unwinding events. In addition, it is puzzling that although monomeric and dimeric helicases should function by distinct mechanisms, the DNA unwinding step sizes of the dimeric PcrA (4 bp, this study), UvrD (4.4 bp; 40) and Rep (4.5 bp; 13) are quite similar to that of the monomeric Dda (5.3 bp; 18,43), RecQ (4 bp; 20), NS3h (3.6 bp; 49) and the 2B-domain-deleted Rep (RepΔ2B) (4 bp; 48). Further studies are needed for more understanding of the DNA unwinding mechanism of PcrA.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to the very helpful suggestions of the referee. We thank Dr D. B. Wigley for his helps in the experiments and for his critical comments on the manuscript. This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the Innovation Project of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, the Institut Curie and the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS) (to X.G.X.). Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by CNRS.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Matson SW, Kaiser-Rogers KA. DNA helicases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1990;59:289–329. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.59.070190.001445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lohman TM, Bjornson KP. Mechanisms of helicase-catalyzed DNA unwinding. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1996;65:169–214. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.001125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singleton MR, Wigley DB. Modularity and specialization in superfamily 1 and 2 helicases. J. Bacteriol. 2002;184:1819–1826. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.7.1819-1826.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.von Hippel PH, Delagoutte E. Macromolecular complexes that unwind nucleic acids. Bioessays. 2003;25:1168–1177. doi: 10.1002/bies.10369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patel SS, Donmez I. Mechanisms of helicases. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:18265–18268. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R600008200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patel SS, Picha KM. Structure and function of hexameric helicases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2000;69:651–697. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.San Martin MC, Stamford NPJ, Dammerova N, Dixon NE, Carazo JM. A structural model for the Escherichia coli DnaB helicase based on electron microscopy data. J. Struct. Biol. 1995;114:167–176. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1995.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dong F, Gogol EP, von Hippel PH. The phage T4-coded DNA replication helicase (gp41) forms a hexamer upon activation by nucleoside triphosphate. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:7462–7473. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.13.7462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Norcum MT, Warrington JA, Spiering M, Ishmael FT, Trakselis MA, Benkovic SJ. Architecture of the bacteriophage T4 primosome: Electron microscopy studies of helicase (gp41) and primase (gp61) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:3623–3626. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500713102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Egelman EH, Yu X, Wild R, Hingorani MM, Patel SS. Bacteriophage T7 helicase/primase proteins form rings around single-stranded DNA that suggest a general structure for hexameric helicases. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:3869–3873. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.9.3869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singleton MR, Sawaya MR, Ellenberger T, Wigley DB. Crystal structure of T7 gene 4 ring helicase indicates a mechanism for sequential hydrolysis of nucleotides. Cell. 2000;101:589–600. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80871-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bjornson KP, Amaratunga M, Moore KJ, Lohman TM. Single-turnover kinetics of helicase-catalyzed DNA unwinding monitored continuously by fluorescence energy transfer. Biochemistry. 1994;33:14306–14316. doi: 10.1021/bi00251a044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng W, Hsieh J, Brendza KM, Lohman TM. E. coli Rep oligomers are required to initiate DNA unwinding in vitro. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;310:327–350. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ha T, Rasnik I, Cheng W, Babcock HP, Gauss G, Lohman TM, Chu S. Initiation and re-initiation of DNA unwinding by the Escherichia coli Rep helicase. Nature. 2002;419:638–641. doi: 10.1038/nature01083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Myong S, Rasnik I, Joo C, Lohman TM, Ha T. Repetitive shuttling of a motor protein on DNA. Nature. 2005;437:1321–1325. doi: 10.1038/nature04049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McGlynn P, Mahdi AA, Lloyd RG. Characterisation of the catalytically active form of RecG helicase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:2324–2332. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.12.2324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morris PD, Tackett AJ, Babb K, Nanduri B, Chick C, Scott J, Raney KD. Evidence for a functional monomeric form of the bacteriophage T4 Dda helicase. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:19691–19698. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010928200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nanduri B, Byrd AK, Eoff RL, Tackett AJ, Raney KD. Pre-steady-state DNA unwinding by bacteriophage T4 Dda helicase reveals a monomeric molecular motor. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:14722–14727. doi: 10.1073/pnas.232401899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu HQ, Deprez E, Zhang AH, Tauc P, Ladjimi MM, Brochon JC, Auclair C, Xi XG. The Escherichia coli RecQ helicase functions as a monomer. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:34925–34933. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303581200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang X-D, Dou S-X, Xie P, Hu JS, Wang P-Y, Xi XG. Escherichia coli RecQ is a rapid, efficient, and monomeric helicase. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:12655–12663. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513089200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levin MK, Wang Y-H, Patel SS. The functional interaction of the hepatitis C virus helicase molecules is responsible for unwinding processivity. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:26005–26012. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403257200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim JL, Morgenstern KA, Griffith JP, Dwyer MD, Thomson JA, Murcko MA, Lin C, Caron PR. Hepatitis C virus NS3 RNA helicase domain with a bound oligonucleotide: the crystal structure provides insights into the mode of unwinding. Structure. 1998;6:89–100. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(98)00010-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singleton MR, Scaife S, Wigley DB. Structural analysis of DNA replication fork reversal by RecG. Cell. 2001;107:79–89. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00501-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bernstein DA, Zittel MC, Keck JL. High-resolution structure of the E. coli RecQ helicase catalytic core. EMBO J. 2003;22:4910–4921. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petit M-A, Dervyn E, Rose M, Entian K-D, McGovern S, Ehrlich SD, Bruand C. PcrA is an essential DNA helicase of Bacillus subtilis fulfilling functions both in repair and rolling-circle replication. Mol. Microbiol. 1998;29:261–273. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Soultanas P, Dillingham MS, Papadopoulos F, Phillips SEV, Thomas CD, Wigley DB. Plasmid replication initiator protein RepD increases the processivity of PcrA DNA helicase. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:1421–1428. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.6.1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Subramanya HS, Bird LE, Brannigan JA, Wigley DB. Crystal structure of a DExx box helicase. Nature. 1996;384:379–383. doi: 10.1038/384379a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Velankar SS, Soultanas P, Dillingham MS, Subramanya HS, Wigley DB. Crystal structures of complexes of PcrA DNA helicase with a DNA substrate indicate an inchworm mechanism. Cell. 1999;97:75–84. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80716-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bird LE, Brannigan JA, Subramanya HS, Wigley DB. Characterisation of Bacillus stearothermophilus PcrA helicase: evidence against an active rolling mechanism. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:2686–2693. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.11.2686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dillingham MS, Wigley DB, Webb MR. Demonstration of unidirectional single-stranded DNA translocation by PcrA helicase: measurement of step size and translocation speed. Biochemistry. 2000;39:205–212. doi: 10.1021/bi992105o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Soultanas P, Dillingham MS, Wiley P, Webb MR, Wigley DB. Uncoupling DNA translocation and helicase activity in PcrA: direct evidence for an active mechanism. EMBO J. 2000;19:3799–3810. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.14.3799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Soultanas P, Wigley DB. DNA helicases: ‘inching forward’. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2000;10:124–128. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(99)00059-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ali JA, Maluf NK, Lohman TM. An oligomeric form of E. coli UvrD is required for optimal helicase activity. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;293:815–834. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maluf NK, Fischer CJ, Lohman TM. A dimer of Escherichia coli UvrD is the active form of the helicase in vitro. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;325:913–935. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01277-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Korolev S, Hsieh J, Gauss GH, Lohman TM, Waksman GH. Major domain swiveling revealed by the crystal structures of complexes of E. coli Rep helicase bound to single-stranded DNA and ADP. Cell. 1997;90:635–647. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80525-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mechanic LE, Hall MC, Matson SW. Escherichia coli DNA helicase II is active as a monomer. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:12488–12498. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.18.12488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee J, Yang W. UvrD helicase unwinds DNA one base pair at a time by a two-part power stroke. Cell. 2006;127:1349–1360. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Niedziela-Majka A, Chesnik MA, Tomko EJ, Lohman TM. Bacillus stearothermophilus PcrA monomer is a single-stranded DNA translocase but not a processive helicase in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:27076–27085. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704399200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Levin MK, Patel SS. Helicase from hepatitis C virus, energetics of DNA binding. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:29377–29385. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112315200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ali JA, Lohman TM. Kinetic measurement of the step size of DNA unwinding by Escherichia coli UvrD helicase. Science. 1997;275:377–380. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5298.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dou S-X, Wang P-Y, Xu HQ, Xi XG. The DNA binding properties of the Escherichia coli RecQ helicase. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:6354–6363. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311272200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Runyon GT, Wong I, Lohman TM. Overexpression purification DNA binding and dimerization of the Escherichia coli uvrD gene product (helicase II) Biochemistry. 1993;32:602–612. doi: 10.1021/bi00053a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Byrd AK, Raney KD. Increasing the length of the single-stranded overhang enhances unwinding of duplex DNA by bacteriophage T4 Dda helicase. Biochemistry. 2005;44:12990–12997. doi: 10.1021/bi050703z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dillingham MS, Wigley DB, Webb MR. Direct measurement of single-stranded DNA translocation by PcrA helicase using the fluorescent base analogue 2-aminopurine. Biochemistry. 2002;41:643–651. doi: 10.1021/bi011137k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fischer CJ, Maluf NK, Lohman TM. Mechanism of ATP-dependent translocation of E. coli UvrD monomers along single-stranded DNA. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;344:1287–1309. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Byrd AK, Raney KD. Displacement of a DNA binding protein by Dda helicase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:3020–3029. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cheng W, Brendza KM, Gauss GH, Korolev S, Waksman G, Lohman TM. The 2B domain of the Escherichia coli Rep protein is not required for DNA helicase activity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:16006–16011. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242479399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brendza KM, Cheng W, Fischer CJ, Chesnick MA, Niedziela-Majka A, Lohman TM. Autoinhibition of Escherichia coli Rep monomer helicase activity by its 2B subdomain. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:10076–10081. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502886102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dumont S, Cheng W, Serebrov V, Beran RK, Tinoco I., Jr., Pyle AM, Bustamante C. RNA translocation and unwinding mechanism of HCV NS3 helicase and its coordination by ATP. Nature. 2006;439:105–108. doi: 10.1038/nature04331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]