Abstract

Consistent laterality is a fascinating problem, and study of the Xenopus embryo has led to molecular characterization of extremely early steps in left-right patterning: bioelectrical signals produced by ion pumps functioning upstream of asymmetric gene expression. Here, we reveal a number of novel aspects of the H+/K+-ATPase module in chick and frog embryos. Maternal H+/K+-ATPase subunits are asymmetrically localized along the left-right, dorso-ventral, and animal-vegetal axes during the first cleavage stages, in a process dependent on cytoskeletal organization. Using a reporter domain fused to molecular motors, we show that the cytoskeleton of the early frog embryo can provide asymmetric, directional information for subcellular transport along all three axes. Moreover, we show that the Kir4.1 potassium channel, while symmetrically expressed in a dynamic fashion during early cleavages, is required for normal LR asymmetry of frog embryos. Thus, Kir4.1 is an ideal candidate for the K+ ion exit path needed to allow the electroneutral H+/K+-ATPase to generate voltage gradients. In the chick embryo, we show that H+/K+-ATPase and Kir4.1 are expressed in the primitive streak, and that the known requirement for H+/K+-ATPase function in chick asymmetry does not function through effects on the circumferential expression pattern of Connexin43. These data provide details crucial for the mechanistic modeling of the physiological events linking subcellular processes to large-scale patterning and suggest a model where the early cytoskeleton sets up asymmetric ion flux along the left-right axis as a system of planar polarity functioning orthogonal to the apical-basal polarity of the early blastomeres.

Keywords: H, K-ATPase, ion flow, left-right asymmetry, laterality, ion pumps, Kir4.1, polarity

Introduction

Vertebrate embryos (and many invertebrates) exhibit a strikingly conserved left-right (LR) asymmetry of the internal organs (Neville, 1976; Palmer, 1996; Palmer, 2004). This is most obvious in the orientation of cardiac and visceral morphogenesis; in a number of vertebrates, this phenomenon also encompasses asymmetries in the brain, with important implications for behavior and cognition (Harnad, 1977; McManus, 2002). The establishment of left-right asymmetry is a fascinating aspect of embryogenesis, raising profound questions about evolutionary conservation of developmental mechanisms and complex regulatory networks (Levin, 2005; Levin, 2006; Raya and Belmonte, 2006). LR patterning is also of considerable clinical interest, since abnormalities in the development of laterality form a class of human birth defects with significant health implications (Burn, 1991; Casey, 1998; Kosaki and Casey, 1998; Ramsdell, 2005).

Conceptually, LR patterning can be divided into three stages (Levin and Mercola, 1998b). In the final phase, individual organs utilize differential cell migration, proliferation, adhesion, and other mechanisms to achieve asymmetries in their location or morphogenesis (Horne-Badovinac et al., 2003; Muller et al., 2003; Zamir et al., 2003). Upstream lies a pathway of asymmetric genes that are expressed in cell fields only on one side of the embryo's midline and propagate signals that dictate sidedness for the organs (Burdine and Schier, 2000; Levin and Mercola, 1998b). These cascades of asymmetric gene expression form the middle phase of LR patterning, which is the best-understood aspect of laterality (Burdine and Schier, 2000; Levin, 1998; Ramsdell and Yost, 1998). However, the crucial steps initiating asymmetric gene expression are still poorly understood: for whichever asymmetric gene is at the top of the pathway, it is necessary to ask what determines its asymmetry. Thus, in the first phase of LR patterning, the left-right axis must be oriented with respect to the other two axes by a different mechanism. The conservation of early mechanisms are currently controversial (Levin, 2003; Levin, 2006; Tabin, 2005; Yost, 2001), but it has been hypothesized that the initial orientation event must take place on the level of single cells (Brown and Wolpert, 1990), making LR patterning an ideal context in which to understand the imposition of large-scale pattern on cell fields by subcellular signals.

Data from mouse mutant analysis have suggested models whereby the movement of monocilia on the node during gastrulation produces LR asymmetric expression of Nodal genes (McGrath and Brueckner, 2003; Okada et al., 2005; Tabin and Vogan, 2003). However, work in chick and Xenopus has identified physiological asymmetries in pH and membrane voltage that occur and function in the LR pathway well before the appearance of cilia or a mature node in those species (Levin, 2004b). That ion channels, ion pumps, and gap junctions function in left-right asymmetry at early stages (Adams et al., 2006; Levin and Mercola, 1998a; Levin and Mercola, 1999; Levin et al., 2002; Raya et al., 2004) suggests a “module” of functionally-related physiological mechanisms that operates upstream of asymmetric gene expression and integrates signals that ultimately feed into downstream transcriptional cascades (Levin, 2006; Raya and Belmonte, 2006).

Hierarchical drug screens (Adams and Levin, 2006a; Adams and Levin, 2006c) first implicated specific ion transporters involved in LR asymmetry. To date, work in the chick, frog, and zebrafish has identified and characterized two ion pumps: the H+/K+-ATPase exchanger and the V-ATPase H+ pump, whose activities are required for correct LR asymmetry of markers and organ situs (Adams et al., 2006; Kawakami et al., 2005; Levin et al., 2002). In frog embryos, the physiological asymmetries appear to be driven by differential localization of maternal ion transporter mRNA and protein subunits along the LR axis (Adams et al., 2006; Levin et al., 2002; Qiu et al., 2005). Thus, the early Xenopus embryo provides an extremely useful system in which to characterize the molecular basis of the physiological signals directing LR axial patterning, and reveal the steps leading from ion flows to downstream events in the LR pathway.

Despite the progress that has been made, in order to synthesize the genetic, cell-biological, and biophysical data into predictive, quantitative, comprehensive models of early LR patterning, a number of key elements of this system remain to be understood (Esser et al., 2006). First, asymmetric localization of the protein components of the H+/K+-ATPase has not been demonstrated – it is still unknown whether the maternal protein is differentially localized across the early midline. Second, it is unknown whether the H+/K+-ATPase protein distribution in the chick is symmetrical (like the mRNA); this is important because it is not clear how the asymmetries in membrane voltage in the chick primitive streak arise. Third, the data have indicated that asymmetries in membrane voltage may arise from the cooperation between the electroneutral H+/K+-ATPase and a K+ channel; while gain-of-function data for Kir4.1 (Bir10, KCNJ10) channels in Xenopus asymmetry have been reported (Levin et al., 2002), no K+ channel candidate for this role has been characterized or functionally tested. Finally, although it has been hypothesized that cytoskeletal elements are responsible for LR-asymmetric localization of maternal proteins (Levin, 2003; Levin and Nascone, 1997), little information is available on possible directional cues natively provided to intracellular transport machinery, which would explain asymmetric localization of important cargo such as ion pump proteins. Here we present a characterization of the H+/K+-ATPase and the Kir4.1 channel during Xenopus cleavage stages that reveals asymmetric localization of H+/K+-ATPase protein at the 4-cell stage, characterizes H+/K+-ATPase protein localization in chick embryos, demonstrates that the symmetrically-expressed Kir4.1 protein is required for normal asymmetry in frog embryos, and illustrates a variety of dynamic subcellular localizations, of both ion transporters, that are dependent on cytoskeletal organization. Moreover, we reveal the fascinating finding that the early embryo contains subcellular transport cues that allow motor proteins to consistently localize along the animal-vegetal, left-right, and dorso-ventral axes. Taken together, these data reveal a profound linkage of apical-basal and planar polarity in the early blastomeres, which form an orthogonal space for the orientation of early bioelectrical signals in left-right patterning.

Results

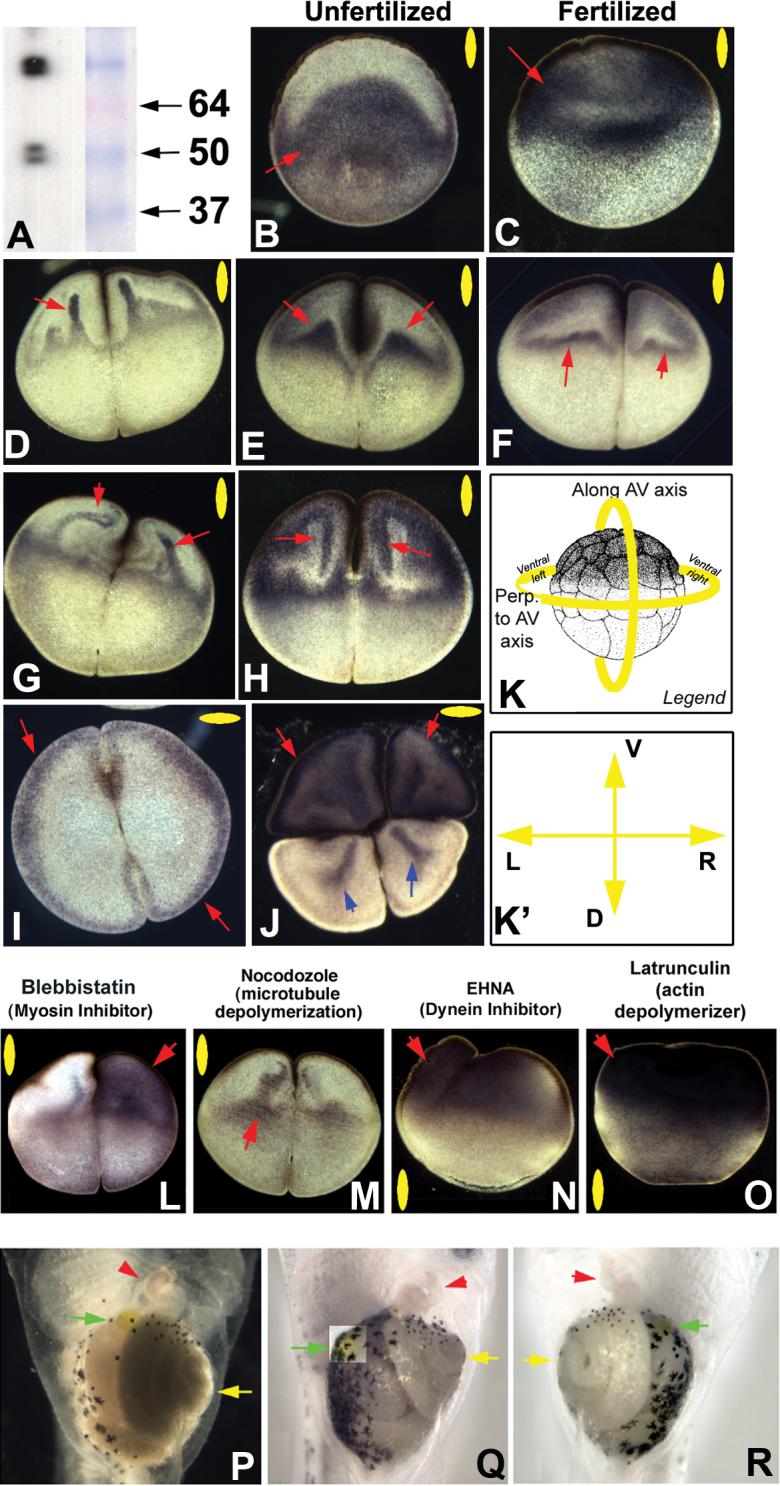

H+/K+-ATPase protein exhibits dynamic and asymmetric localization at cleavage stages

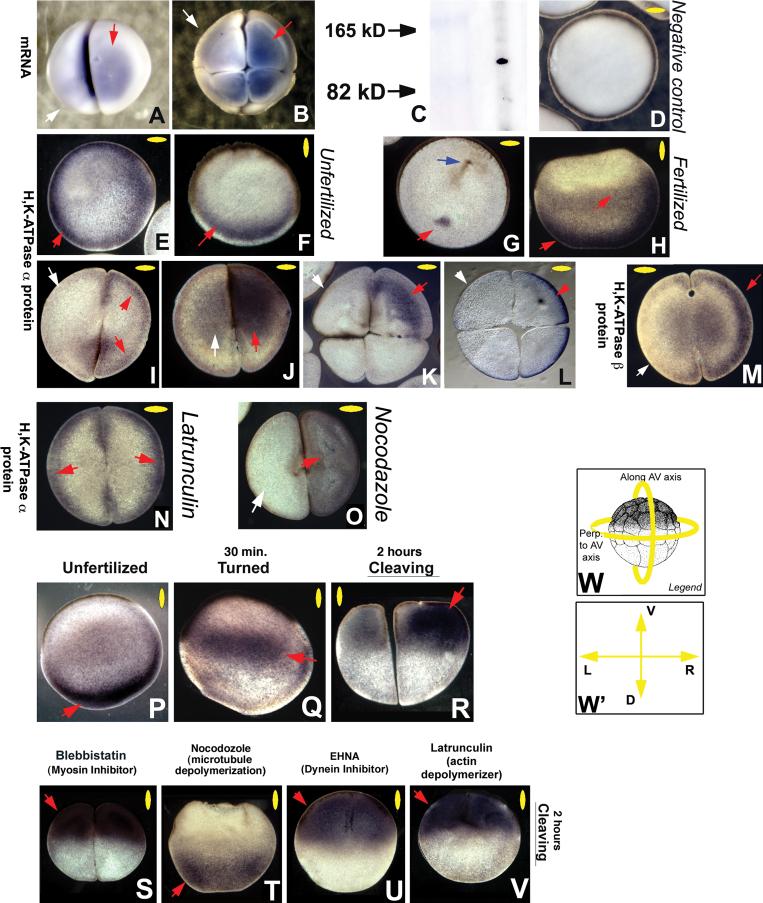

While maternal H+/K+-ATPase mRNA is asymmetrically localized by the 4-cell stage (Fig. 1A,B, Levin et al., 2002), the distribution of H+/K+-ATPase proteins has not been shown. This is important because maternal proteins can be stored in locations in which mRNA does not exist, and conversely, maternal mRNA may not be translated into mature protein. Thus, information on the protein complex localization is required to formulate and test specific models of ion-dependent signaling in LR patterning. To this end, we performed immunohistochemistry on sections of oriented Xenopus embryos as previously described (Levin, 2004a), using well-characterized antibodies (Chen et al., 1998) raised to native frog H+/K+-ATPase α and β subunits (Fig. 1C). Negative controls revealed the expected lack of signal (Fig. 1D). In contrast, unfertilized eggs exhibited a radially-symmetric distribution of maternal H+/K+-ATPase α protein (Fig. 1E) that was largely confined to the vegetal pole of the egg (Fig. 1F). Upon fertilization, a discrete focus of localization can be observed at 180° to the sperm path (Fig. 1G), and a considerable amount of maternal protein was detected throughout the vegetal half of the egg (Fig. 1H). During the first cleavage, H+/K+-ATPase α protein is detected in one of the two blastomeres in >75% of the sections examined, either at the membrane (Fig. 1I) or throughout the cytoplasm (Fig. 1J). The same is true of the accessory β subunit of the H+/K+-ATPase (Fig. 1M). This asymmetric localization is revealed to be right-sided (Fig. 1K,L) at the 4-cell (at which time the orientation of the sections can be determined). We conclude that the H+/K+-ATPase exhibits asymmetric localization at the protein level during early Xenopus cleavages along both the LR and animal-vegetal (AV) axes.

Figure 1. H+/K+-ATPase is dynamically and asymmetrically localized in the early frog embryo.

mRNA encoding the α subunit of the H+/K+-ATPase is asymmetrically localized at the 2 cell stage (A), and revealed to be right-sided by the 4-cell stage (B). Antibodies developed to the Xenopus H+/K+-ATPase α subunit give a single clean band of the predicted size in Western blots (C) and were used to examine protein localization (which does not always match mRNA because of maternal contributions and post-transcriptional regulation) by immunohistochemistry using alkaline-phosphatase chromogenic detection on sections (purple signal). “No primary” negative controls gave the predicted lack of signal (D). Localization of H+/K+-ATPase α subunit protein was detected circumferentially (E) in a region at the vegetal pole (F) of unfertilized eggs. At fertilization, a specific spot of H+/K+-ATPase α protein was detected at 180° opposite the sperm entry point (blue arrow, G), and H+/K+-ATPase α protein became spread out toward the anterior pole, then occupying more than half of the embryo (H). At the 2-cell stage, asymmetric localization of the H+/K+-ATPase α subunit was detected at the cell membrane on sections taken through the animal hemisphere (I) and throughout the cytoplasm in sections taken through the vegetal hemisphere (J). By the 4-cell stage, the localization was confined to the right ventral hemisphere (K, taken more vegetally, and L, taken more animally). The H+/K+-ATPase β subunit was likewise asymmetric at the 2-cell stage (M). The asymmetric localization was abolished (bilateral cell membrane staining) by exposure to the actin disruptor Latrunculin (N). In contrast, the microtubule disruptor Nocodazole did not interfere with asymmetric localization (O), but did loosen the association of the protein with the membrane. Section O had to be taken in a less apical plane than sections for untreated embryos, because these drugs interfered with the normal animal-pole localization of these proteins (see below).

In addition to the localization along the LR and dorso-ventral axes, we detected dynamic localization of the H+/K+-ATPase along the animal-vegetal axis. While the H+/K+-ATPase α protein is tightly localized to the vegetal cortex before fertilization (P), the band of protein rises towards the animal pole after fertilization (Q) and ultimately settles under the animal pole surface (R). This localization was not disrupted by Blebbistatin, an inhibitor of myosin (S), but was abolished by Nocodazole (T). Inhibition of Dynein (U) or disruption of the actin cytoskeleton (V) had no effect on the normal animal-pole localization of H+/K+-ATPase α subunit. Note that the embryos in T-V were at the same age (equivalent to the 2-cell stage) as those in panel R: the cell cleavage plane is not apparent in these embryos because the efficient disruption of the cytoskeleton and motor protein machinery interferes with cytokinesis.

Red arrows indicate positive signal; white arrows indicate lack of signal. Yellow ovals in each panel indicate plane of section, as illustrated in panel W; orientation of sections taken perpendicular to the AV axis is shown in W’.

H+/K+-ATPase localization along two axes is dependent on intracellular transport machinery

Disorganization of the cytoskeleton by UV irradiation (Yost, 1991) or by specific drugs (Qiu et al., 2005) results in LR randomization. Moreover, a number of LR-relevant proteins' asymmetric localizations require intact cytoskeletal organization (Adams et al., 2006; Qiu et al., 2005). Thus, to test whether asymmetrical localization of H+/K+-ATPase proteins is dependent on cytoskeletal elements, we performed immunohistochemistry with H+/K+-ATPase α antibodies on sections of embryos treated (immediately after de-jellying) with disruptors of microtubule organization (Nocodazole) or actin filament organization (Latrunculin), as has previously been done to analyze localization of other LR-relevant maternal proteins (Adams et al., 2006; Qiu et al., 2005). We observed that asymmetry at the 2-cell stage was lost as a result of Latrunculin treatment (Fig. 1N), but largely maintained after exposure to Nocodazole (Fig. 1O, compare to 1J). These results suggest that the asymmetry of H+/K+-ATPase localization along the left-right axis is dependent on microfilaments but not microtubule organization.

Because the α subunit of the H+/K+-ATPase also exhibits dynamic movement along the animal-vegetal axis (Fig. 1F,H), we examined the dependence of AV localization on intracellular transport machinery (cytoskeletal components and motor proteins). Unfertilized eggs tightly localize their H+/K+-ATPase to the vegetal pole (Fig. 1P). Immediately after fertilization, the mass of maternal H+/K+-ATPase protein begins to spread (Fig. 1H) and rise (Fig. 1Q) and is located halfway between the animal and vegetal poles (Fig. 1Q). By the first cell cleavage, most of the protein has accumulated near the animal pole (Fig. 1R). This animal-pole localization was not altered by inhibition of myosin (Fig. 1S). In contrast, depolymerization of microtubules by Nocodazole prevented the movement and resulted in maintenance of the vegetal localization until at least 2 hours post-fertilization (Fig. 1T). Inhibition of dynein function or actin polymerization did not prevent animal-pole localization of the H+/K+-ATPase even though cell division was inhibited at these doses (Fig. 1U,V). We conclude that the movement of maternal H+/K+-ATPase proteins along the animal-vegetal axis during the first 2 hours of development requires functional microtubules, but not microfilaments, myosin, or dynein motor function.

The early cytoskeleton can provide consistent LR cues

What mechanism might be responsible for LR-asymmetric localization of ion transporter subunits? We have previously proposed models whereby molecular motors such as kinesin and dynein achieve asymmetric distributions of ion transporter protein cargo (Levin, 2003; Levin and Nascone, 1997). Movement of such motors requires cytoskeletal tracks, and, indeed our data above suggest that different cytoskeletal elements may bear specific directional cues for transporting various cargo in different directions to achieve functionally significant localizations. Hence, we next asked whether the native cytoskeleton might bear LR information (confer an asymmetric bias to cytoplasmic motor movement). Following the strategy successfully used in Drosophila to probe the directionality of the embryonic cytoskeleton (Clark et al., 1994; Clark et al., 1997), we generated mRNA encoding a lacZ reporter gene fused to kinesin heavy chain (KHC), which moves towards the + end of microtubules, and a different RNA encoding the lacZ reporter fused to a kinesin-related protein (NOD), which moves towards the – end of microtubules. We sought to use the localization of β-gal stain, after expression of these chimeric constructs, as a readout of the native bias of the microtubule cytoskeleton in the early frog embryo.

Embryos were injected (immediately after fertilization) with a control β-gal mRNA or mRNAs encoding the NOD:lacZ or KHC:lacZ fusion construct. At the 4-cell stage, embryos with evident LR and DV axes were fixed, embedded in consistent LR orientation and sectioned in two planes: along, or perpendicular to, the animal-vegetal axis. Sections were processed for β-gal staining and scored for localization of the blue stain in the blastomeres (see Table 1a-c for raw counts and statistical analysis using contingency table χ2 tests).

Table 1a. Lac-Z enzyme fused to motor proteins reveal endogenous polarity in cytoplasmic transport machinery. localization of motor proteins along left-right axis.

Left column labels are: L = left; R = right; b = both; D = dorsal; V=ventral, schematized by blastomere position in the diagrams to the left (showing an animal-pole view of a 4-cell embryo, oriented with the ventral side toward the top of the page). Control β-gal injected embryos resulted in a total of 33 left blastomeres exhibiting signal, and 28 right blastomeres total exhibiting signal (e.g., a “bD” or “bV” section contributes 1 count to the L total and 1 to the R total, while a “Lb” section contributes 2 counts to the L total because 2 different left blastomeres were positive for signal). Dorsal and Ventral counts were 30 and 31 respectively. Nod+β-gal injected embryos resulted in a total of 38 left blastomeres and 31 right blastomeres exhibiting signal. Dorsal and ventral counts were 67 ventral and 2 dorsal. In contrast, KHC+β-gal injected embryos exhibited signal in 2 left blastomeres and 20 right blastomeres. Dorsal and ventral counts were 14 ventral and 8 dorsal. Statistics: Nod localizes to the ventral half (χ2 = 37.1, p<0.001); KHC localizes to the Right half (χ2 =15.6, p<0.001).

| Localization: | Control β-gal | Nod+β-gal | KHC+β-gal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

LV | 3 | 19 | 2 |

|

RV | 1 | 12 | 9 |

|

LD | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

RD | 1 | 0 | 5 |

|

bD | 9 | 0 | 0 |

|

Rb | 1 | 0 | 3 |

|

Lb | 3 | 0 | 0 |

|

bV | 8 | 17 | 0 |

|

RD+LV | 1 | 0 | 0 |

|

LD+RV | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

All 4 | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| Total: | 30 | 49 | 18 | |

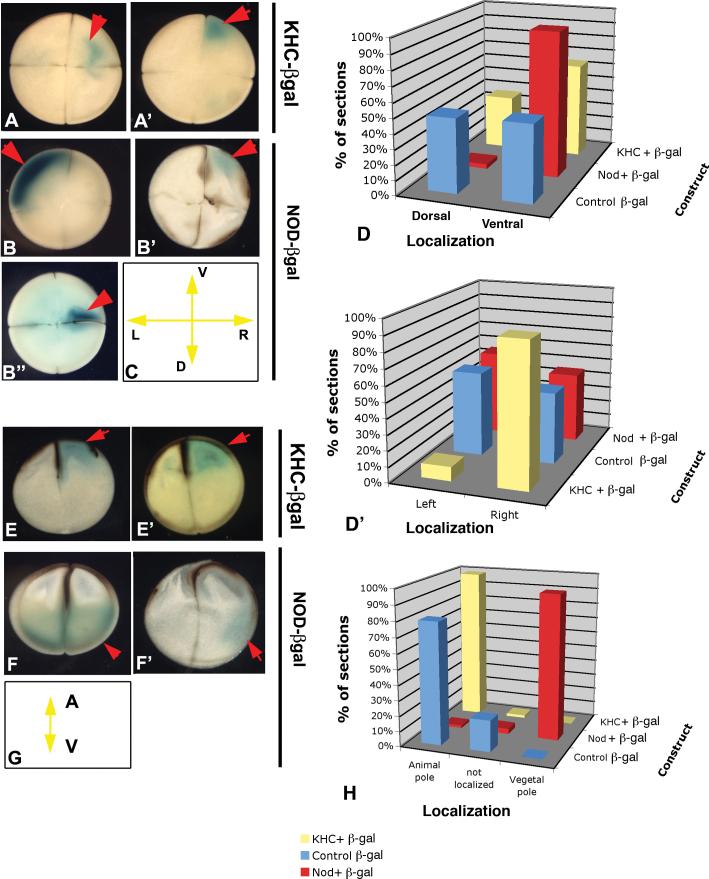

Sections taken perpendicular to the animal-vegetal axis revealed that free β-gal, not fused to any motor protein (to reveal the baseline tendency for injected mRNA to localize) had no preference along the LR or DV axes. In contrast, KHC-driven β-gal tended to accumulate in the right blastomeres (Fig. 2A,A’) in a 10:1 preference over the left blastomere (p<0.01). A weaker but not significant preference for the ventral side was also observed. In contrast, NOD-driven β-gal had a very strong ventral preference (p<0.01) but roughly equal localization along the LR axis (Fig. 2B,B’,B”). The section orientations are schematized in Fig. 2C and the data are summarized by the histograms in Fig. 2D,D’.

Figure 2. The early embryo provides directional information for motor protein transport along all three axes.

To test for possible bias in the intracellular tracks available to the motor transport machinery, mRNA encoding β-gal enzyme fused to a kinesin heavy chain domain (KHC, which travels towards the “+” end of microtubules) was microinjected into the center of the animal pole of eggs immediately after fertilization. Embryos were sectioned in consistent orientation and processed for β-gal stain as a readout of endogenous directionality in the embryonic cytoskeleton. Raw data of the resulting localization of blue signal in each embryo are reported in Table 1a. The majority of KHC-β-gal stain was localized to the right side (A,A’), with a moderate bias for ventral blastomeres. In contrast, signal from injections of NOD-β-gal (a kinesin-like protein that ravels towards the “-“ end of microtubules) was randomly distributed along the LR axis (B,B’, with occasional association with one half of a cleavage furrow, B”), as was control mRNA encoding just β-gal enzyme. NOD-β-gal was asymmetrically (and randomly) localized in 63% of the cases (N=49). Panel C schematizes the orientation of sections A-B”. The directional data are summarized in panels D and D’. While plain β-gal mRNA does not become asymmetrically localized along the dorsosoventral axis, KHC-β-gal possesses a weak tendency towards the ventral side, while NOD-β-gal is strongly transported towards the ventral side (D). While neither plain β-gal nor NOD-β-gal mRNA is preferentially localized along the LR axis, KHC–β-gal is strongly biased for the right side.

To test for similar biases along the animal-vegetal (AV) axis, mRNA was injected equatorially. Raw data of the resulting localization of blue signal in each embryo are reported in Table 1b. The tendency of control β-gal mRNA to travel towards the animal pole was even more strongly observed for the KHC-β-gal protein (E,E’). In contrast, NOD-β-gal strongly reversed this tendency, being targeted towards the vegetal pole (F,F’). Panel G schematizes the orientation of sections E-F’. The different destinations of the NOD and KHC motor proteins are summarized in the histogram in H. The synthesis of these data on the directions of tracks along all three dimensions is shown in Table 1c. In all panels, red arrows indicate positive signal (blue-green).

Sections taken along the animal-vegetal axis revealed that the β-gal negative control has about a 4:1 preference for the animal pole (31 of 39 sections). KHC-driven β-gal is even more strongly driven towards the animal pole (56 of 57 sections; Fig. 2E,E’, p<0.05); in contrast, NOD-driven β-gal was observed almost entirely in the vegetal pole (54 of 57 sections; Fig. 2F,F’; p<0.01). The section orientations are schematized in Fig. 2G, and the data are summarized by the histogram in Fig. 2H.

Thus, the “+”-end-seeking KHC is strongly targeted to the right ventral side of the animal pole. In contrast, the “–“-end-seeking NOD is strongly targeted to the ventral vegetal pole (Table 1c). These striking patterns demonstrate that elements of the microtubule cytoskeleton, and perhaps other cues in the cleavage-stage Xenopus embryo, contain biases along all three axes, which are sufficient to confer an asymmetric directionality to cargo molecules' movement.

H+/K+-ATPase protein is present in the streak-stage chick embryo

Recent data indicates that while the chick and frog rely on some of the same molecular components during the physiological signaling of early LR axial patterning, the details of these mechanisms' use in embryos with such different gastrulation modes are significantly different (Adams et al., 2006; Fukumoto et al., 2005b; Levin and Mercola, 1998a; Levin and Mercola, 1999; Levin et al., 2002; Raya et al., 2004). Differences in expression and localization of targets between these two species, and, in particular, the lack of known asymmetric mRNA localization of any ion transporters in the chick (in contrast to the frog) have made it difficult to develop a model that adequately explains the early events in both model systems (Levin, 2005). Thus, to test the hypothesis that asymmetric localization of this ion exchanger protein may underlie the one-sided hyperpolarization in the streak, we examined the localization of H+/K+-ATPase subunits in chick.

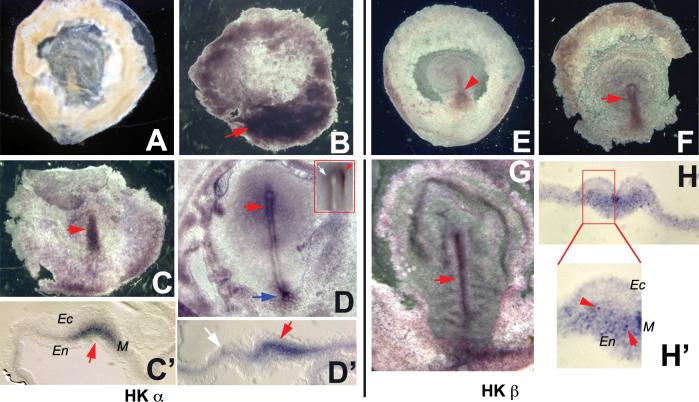

Controls exhibited the expected lack of signal (Fig. 3A). Chick embryos at streak initiation (st. 1) exhibited a domain of H+/K+-ATPase subunit α protein in the area opaca under the primitive streak (Fig. 3B). The protein is present in the mesoderm of the early streak during elongation (Fig. 3C,C’). At mature streak stages (St. 4+), H+/K+-ATPase subunit α is present in the ridges of the primitive streak (Fig. 3D) as well as in the base of the streak (Fig. 3D, blue arrow). Strikingly, the expression in the node is asymmetric (right-sided, insert in Fig. 3D, confirmed in section in Fig. 3D’) at st. 4+ in 5 out of 12 embryos examined. H+/K+-ATPase subunit β is similarly expressed in the streak (Fig. 3E-G), but with no evidence of LR asymmetry. Sectioning revealed that unlike the α subunit, which is broadly expressed in the mesoderm (Fig. 3C’), the β subunit is present in a speckled (punctate) pattern in a small subset of mesodermal cells (Fig. 3H,H’). We conclude that the H+/K+-ATPase proteins are present in the primitive streak of early chick embryos and subunit α often exhibits an asymmetric localization in the node at mature streak stages.

Figure 3. Localization of H+/K+-ATPase proteins in the chick embryo.

Chick embryos were subjected to wholemount immunohistochemistry using alkaline-phosphatase chromogenic detection (purple signal). Negative controls (no primary antibody) exhibited the expected lack of signal (A). H+/K+-ATPase α: At st. 1, strong signal was detected at the base of the nascent streak (B). During streak extension (st. 2), streak cells were strongly positive for H+/K+-ATPase (C); sectioning revealed that the stain was in the mesoderm cells (C’). In the mature streak (St. 4+), H+/K+-ATPase α was localized to the primitive ridges, and the base of the streak (blue arrow). In the node, right-sided asymmetric expression was observed (red inset box) in wholemount (D) and confirmed in section (D’).

H+/K+-ATPase β: Signal was first detected weakly in the early streak at st. 2 (E). At stages 3 and 4, stain was likewise observed in the primitive ridges (F,G). Sectioning revealed expression in the mesoderm and endoderm (H, closeup in H’) but in a more punctate pattern (H’) than the more homogenous α subunit (C’,D’). In all panels, red arrows indicate positive signal and white arrows indicate lack of signal. Ec = ectoderm; En = endoderm; M = mesoderm.

Kir4.1 is symmetrically expressed in early frog embryos

A major question concerning the role of the H+/K+-ATPase in LR asymmetry concerns how its net-electroneutral activity can produce the known asymmetry in the membrane voltage of L vs. R cells in the st. 3 streak (since this pump exchanges one positive charge for another across the membrane). Taking a cue from neuronal cells, where K+ channels allow the exit of positive potassium ions brought in by the Na+/K+-ATPase (a P-type pump closely related to the H+/K+-ATPase) resulting in the generation of a stable resting membrane voltage, we tested the hypothesis that Kir4.1 protein may participate in LR patterning. Kir4.1 is a promising candidate because in several tissues, including cochlea and gut, Kir4.1 (also known as Bir10) functions in concert with the H+/K+-ATPase to regulate membrane voltage and K+ content (Fujita et al., 2002; Geibel, 2005). Moreover, our prior data indicated that co-expression of Kir4.1 was necessary to randomize asymmetry by re-capitulating the H+/K+-ATPase-dependent ion gradient on the opposite side (Levin et al., 2002). However, no information on endogenous Kir4.1 in frog embryos has yet been available.

We first examined the localization of Kir4.1 in early frog embryos using an antibody that produced clean bands corresponding to the expected single and dimer subunits of Kir4.1 on Western blots of Xenopus laevis one- cell protein lysates (Fig. 4A). That the antibody recognized a protein of the expected size in Western blots was the first evidence that Kir4.1 is present as maternal protein in the early embryo. The immunohistochemistry showed that prior to fertilization, Kir4.1 protein was present throughout the egg except for a sickle-shaped (in cross-section) area at the animal pole (Fig. 4B). Shortly after fertilization, this pattern is reversed, and the maternal Kir4.1 protein moves towards the animal pole (Fig. 4C). Sections taken along the animal-vegetal axis revealed a strikingly dynamic pattern of “fingers” in the animal pole which appear to follow the curve of the cell surface after reaching the animal pole and form triangle-shaped (in cross section) areas in each blastomere (Fig. D-H). Table 1d provides a summary of H+/K+-ATPase and Kir4.1 protein localizations. These data indicate that subcellular localization “zipcodes” in the early blastomere can exhibit spatial complexity significantly greater than that previously observed in animally- or vegetally-localized maternal components. Sections taken across the animal-vegetal axis revealed localization at the cell membrane from the 2-cell stage (Fig. 4I), and an additional rod-shaped component pointing towards the center of the embryo by the 4-cell stage (Fig. 4J, blue arrow). No evidence of consistent asymmetry was observed. Thus, we conclude that Kir4.1 protein is dynamically but symmetrically localized in the early frog embryo.

Figure 4. Localization and function of Kir4.1 in the frog embryo.

Using antibodies to Kir4.1 that reveal clean bands of the predicted size (corresponding to single subunits and dimers) (A), immunohistochemistry revealed that the unfertilized egg localized Kir4.1 protein throughout the vegetal half, excluding a sickle-shaped (bowl shaped, in 3 dimensions) area under the animal pole (B). In contrast, after fertilization, the protein is located throughout the animal hemisphere (C). At the 2-cell stage, Kir4.1 protein localization exhibits a range of patterns consistent with finger-like projections which can be observed at different stages of a movement from an equatorial pool towards the animal pole (D-F). The patterns are suggestive of a movement that bends to follow the contour of the animal pole edge and then returns to the equatorial pool, forming triangle-like areas including at the cell membrane (F-H).

At the 2-cell stage, localization is symmetrical along the LR axis and results in Kir4.1 presence at the cell cortex in sections taken at the animal pole (I). Sections taken in the vegetal hemisphere exhibit a more complex localization, being present throughout the cytoplasm of the ventral cells and in rod-like patterns in the dorsal cells (blue arrows, J). The normal sequence of animal pole-directed movement of Kir4.1 protein (B-H) was disrupted by manipulation of the cytoplasmic transport machinery. Inhibition of myosin by Blebbistatin often introduced an asymmetry along the LR axis and abolished the appearance of well-defined fingers (L). Depolarization of microtubules somewhat disrupted the well-formed pattern (M). Inhibition of dynein motor protein activity and disruption of the actin cytoskeleton resulted in much more drastic changes in the normal pattern, resulting in most of the Kir4.1 protein localizing to the animal pole in bulk (N,O). Red arrows indicate positive signal. Yellow ovals in each panel indicate plane of section, as indicated in panel K; orientation of sections taken perpendicular to the AV axis is shown in K’.

Functional roles for Kir4.1 in left-right patterning were tested by misexpression of a dominant negative construct designed to trap endogenous Kir4.1 protein subunits in the ER at the 1 cell stage, and scoring laterality of the heart, gut, and gall-bladder at st. 43. The raw data are shown in Table 2. In contrast to control (uninjected) embryos and embryos injected with Kir2.1-ER mRNA, all of which exhibited >97% normal laterality (P), embryos injected with Kir4.1-ER mRNA exhibited 25% incidence of independent randomization of the three organs assayed (heterotaxia), including reversals of the heart (Q), and gut and gall-bladder (R). Red arrowheads indicate apex of the heart; yellow arrowheads indicate direction of gut coil vertex; green arrowhead indicates position of the gall bladder.

We next asked whether the cytoskeleton was important in establishing Kir4.1 distribution, as it has proven to be for the H+/K+-ATPase (Fig. 1O-R) by examining the results of exposure to cytoplasmic localization inhibitors (immediately after fertilization) on the normal animal-vegetal localization pattern at the 2-cell stage (Fig. 4B-H). Inhibition of myosin by Blebbistatin disrupted the subtle pattern of the “fingers” (Fig. 4L). In contrast, Nocodazole did not abolish the appearance of the finger-like localization (Fig. 4M). Exposure to a dynein motor protein inhibitor did not allow formation of the fingers, but still permitted the movement of the protein to the animal pole (Fig. 4N). In contrast, disruption of actin organization prevented the complete movement of maternal Kir4.1 protein away from the animal pole as well as the appearance of the finger-like projections seen in untreated embryos (Fig. 4O). We conclude that Kir4.1 localization is dependent on the actin (and to a lesser extent, tubulin) cytoskeleton and on the dynein and myosin motor proteins, and that movement towards the anterior pole and formation of “fingers” require distinct mechanisms.

Kir4.1 is required for normal LR asymmetry

The involvement of a K+ channel in LR asymmetry was predicted by pharmacological data (Levin et al., 2002), but the molecular identity of the channel involved had not been known. Thus, we probed the functional necessity of Kir4.1 for LR asymmetry by creating a dominant negative construct: a Kir4.1 subunit containing an ER-retention sequence. This powerful technique has been successfully used to reduce the function of a number of inward rectifier K+ channels such as Kir2.1 and Kir6.1 (Cho et al., 2000; Hough et al., 2000; Partridge et al., 2001; Yuan et al., 2003; Zerangue et al., 1999), because the tetrameric channels containing native and exogenous subunits become retained in the endoplasmic reticulum and are depleted from the cell membrane. Introduction of mRNA encoding Kir4.1-ER at the 1 cell stage resulted in 25% of the embryos exhibiting heterotaxia (independent randomization of the heart, gut, and gall-bladder; Fig. 4Q,R, Table 2) in the absence of toxicity or other defects (χ2 = 237, p<0.001, dorso-anterior index=5). In contrast, injections of a dominant negative ER-retention construct for the closely related potassium channel Kir2.1 had no effect on asymmetry (3% heterotaxia vs. 2% in controls; Fig. 4P), demonstrating that the effect is specific for Kir4.1 and is not a general consequence of ER-retention or global K+ channel inhibition. We conclude that Kir4.1 function is required for normal asymmetry in the Xenopus embryo.

Table 2. ER-retention-based Kir4.1 dominant negative construct randomizes LR asymmetry.

Embryos were injected with 1.2−4 ng of mRNA encoding Kir4.1 (Bir10) or Kir2.1 fused to an ER retention tag at the 1 cell stage, and scored for sidedness of heart, gut, and gall-bladder at st. 45. Compared to controls, embryos expressing the dominant negative Kir4.1 exhibited heterotaxia, significant to p<0.001 (χ2 with Pearson correction), while those expressing dominant negative Kir2.1 did not.

| Outcome | control | Kir4.1-ER | Kir2.1-ER | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |||

| Situs solitus (w.t.) | 433 | 98% | 441 | 75% | 351 | 97% |

| Heterotaxia: | 9 | 2% | 146 | 25% | 12 | 3% |

| total: | 442 | 587 | 363 | |||

| Organs Affected | Kir4.1-ER | Kir2.1-ER | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |

| heart | 46 | 32% | 6 | 50% |

| stomach | 20 | 14% | 2 | 17% |

| gall bladder | 1 | 1% | 0 | 0% |

| heart and stomach | 2 | 1% | 0 | 0% |

| heart and gall bladder | 2 | 1% | 0 | 0% |

| stomach and gall bladder | 12 | 8% | 2 | 17% |

| heart, stomach, and gall bladder | 63 | 43% | 2 | 17% |

| total | 146 | 12 | ||

Kir4.1 protein is present in the streak-stage chick embryo

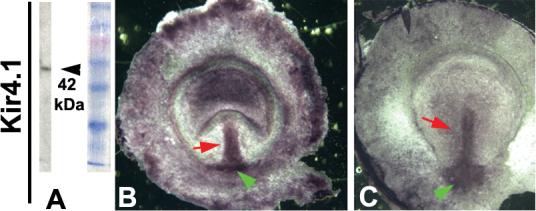

We next checked the presence of Kir4.1 in chick embryos. Western blots on extracts of early chick embryos demonstrated that the Kir4.1 antibody recognizes a clean band of the correct size (Fig. 5A). Immunohistochemistry revealed considerable background, but the strongest expression of Kir4.1 was in the primitive streak and at its base (Fig. 5B,C). No evidence of asymmetric expression was observed, so asymmetry of protein localization cannot be a source of directional information. While no functional data indicate that Kir4.1 is required for chick asymmetry, Kir4.1 is a component whose contribution must be included in models of ion flow in the early chick streak because a valid model should include all known conductances so as to have a complete understanding of the physiological circuit. Indeed, inclusion in quantitative models of ion channels that exist in cells but do not contribute to LR patterning may reveal why a biophysical event does or does not become transduced to downstream LR-relevant mechanisms.

Figure 5. Kir4.1 protein localization in chick.

The Kir4.1 antibody gives a single clean band of the predicted size when used on chick tissues in Western blots (A). In wholemount immunohistochemistry, signal was detected in many locations throughout the area opaca, but most strongly in the streak and its base (B, red and green arrows respectively). Expression outside of the streak lessened with time, leaving symmetrical expression in the streak and the cells at its base at st. 4 (C).

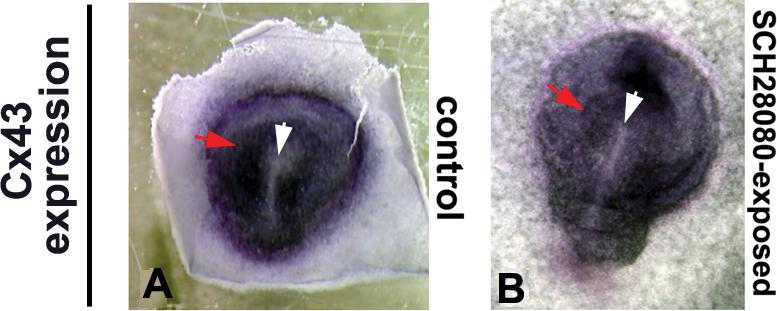

H+/K+-ATPase inhibition does not affect Cx43 expression in chick

We previously showed that inhibiting H+/K+-ATPase function (Levin et al., 2002), or specifically down-regulating Connexin43 expression in chick (Levin and Mercola, 1999), randomizes asymmetry. To examine one possible functional relationship between these two mechanisms, we tested the hypothesis that H+/K+-ATPase activity is required for the normal pattern of Connexin43 expression that establishes a zone of electrical isolation in the streak. Chick embryos were exposed to the H+/K+-ATPase inhibitor SCH28080 in ovo (as described in (Levin et al., 2002) at the start of incubation, and examined for the expression of Connexin43 by in situ hybridization at st. 2+. The normal expression of Connexin43 in a circumferential pattern around the non-expressing early streak after this treatment (Fig. 6A,B) revealed that H+/K+-ATPase function is not required for normal Connexin43 expression.

Figure 6. Radial Connexin43 expression does not depend on H+/K+-ATPase function.

In wild-type chick embryos at st. 3 (A), the gap junction gene Connexin43 is expressed in a radial pattern (red arrow) around a zone of isolation in the primitive streak (white arrow). This pattern was not altered (B) when embryos were exposed in ovo to SCH28080, a potent inhibitor of H+/K+-ATPase function, which is known to randomize LR asymmetry in chick embryos (Levin et al., 2002). Variations in shade of purple stain around the streak are due to natural folding in tissue and do not represent consistent spatiotemporal differences in signal.

Discussion

Two vertebrate embryos differentially localize H+/K+-ATPase and the Kir4.1 ion transporter proteins at very early stages

Subtractive immuno-reactivity techniques have previously been used to identify maternal proteins asymmetrically localized along the animal-vegetal axis of the Xenopus egg (Denegre et al., 1997). Here, we present an analysis of the intracellular localization, along all three axes, of two proteins, forming an ion pump and a channel, that were first suggested as candidates for asymmetric function based on an inverse drug screen in a laterality assay (Adams and Levin, 2006b; Levin et al., 2002). Asymmetric localization of maternal components of the H+/K+-ATPase was observed after the first cleavage in Xenopus (Fig. 1). While the plane of first cleavage can be experimentally repositioned (Black and Vincent, 1988; Danilchik and Black, 1988), in normal embryos the cleavage furrow usually corresponds to the future midline of the embryo (Klein, 1987; Masho, 1990), and injection of one cell at the two-cell stage is routinely used to target half the embryo, allowing the contralateral half to serve as an internal control (Harvey and Melton, 1988; Vize et al., 1991; Warner et al., 1984). Thus, to take a cue from similar data on the V-ATPase H+ pump (Adams et al., 2006), this early asymmetry of protein localization is predicted to align differences in ion flux (and thus, subsequent physiological asymmetries) with the prospective LR axis of the embryo. Moreover, its right-sided activity is likely to be key to the involvement of the H+/K+-ATPase in the elaboration of consistent developmental asymmetry.

The H+/K+-ATPase proteins are dynamically localized not only along the LR axis, but also along the orthogonal animal-vegetal axis (Fig. 1P-R). The localization of the bulk of the pump subunits at the animal pole by cleavage stages is consistent with the appearance of asymmetric H+ fluxes, which have previously been directly detected at the animal surface at the 2- and 4-cell stages (Adams et al., 2006; Levin et al., 2002). The dependence of the H+/K+-ATPase proteins' 3-dimensional localization on cytoskeletal tracks is also consistent with prior data showing the same dependency for a number of asymmetry-relevant proteins, such as KIF3B, LRD, etc. (Qiu et al., 2005), and with our earlier proposal that the asymmetric physiology of the early embryo is set up by motor-protein-dependent patterning of ion transporter localization (Levin, 2006; Levin and Nascone, 1997; Levin and Palmer, 2007).

We have previously shown that H+/K+-ATPase mRNA is also asymmetric at early cleavage stages (Levin et al., 2002). Given that maternal protein is already asymmetric, and that mRNA asymmetrically localized at st. 4 will not be translated in time to provide asymmetric zygotic protein, it is not clear why the embryo should need to localize maternal mRNA. One possibility is that since asymmetric mRNA will not result in asymmetric protein until more than 2 hours after fertilization (after the ion currents necessary for asymmetry must be initiated), the maternal protein is asymmetric at 4 cell stage to rapidly initiate asymmetric physiological states, and the asymmetric mRNA takes over to reinforce the signal at later stages.

One interesting aspect of the localization is the domain on the side opposite the sperm entry point (Fig. 1G). A similar observation was made for components of the V-ATPase (Adams et al., 2006), which are localized at the sperm entry point. While the molecular details of this localization domain will be probed in future work, association with sperm entry is tantalizing in light of our suggestion (see below) that the cytoskeletal rearrangements brought about by the DV axis initiation at sperm entry initially align the LR axis with respect to the AV and DV axes.

The chick embryo expresses H+/K+-ATPase protein at a stage when, unlike the few large blastomeres of Xenopus, there are tens of thousands of small cells. We have previously described asymmetric depolarization at st. 3, which was dependent on H+/K+-ATPase function (Levin et al., 2002). However, the molecular basis for the asymmetry was not clear because no asymmetry in expression (either at mRNA or protein levels) had been described in either H+/K+-ATPase or V-ATPase. While here we did observe a right-sided asymmetry in H+/K+-ATPase protein, which may be related to the later ion flow events linked to Ca++ and Notch signaling (Raya et al., 2004), it occurred in the mature node and is thus too late to account for the asymmetric depolarizations of the early streak. It is likely that either the relevant asymmetrically expressed transporter remains to be identified, or that asymmetric regulatory proteins controlling symmetrically-expressed pumps confer a physiological difference to cells on either side of the early streak.

What is responsible for asymmetric localization?

In light of early work suggesting that organization of the cytoskeleton prior to 1st cleavage is required for LR asymmetry in Xenopus (Yost, 1991), of the well-known role of the cytoskeleton and motor proteins in the localization of subcellular components in many cell types (Denker and Barber, 2002a; Januschke et al., 2002; Lee et al., 1999; Vijayakumar et al., 1999), and of data implicating dyneins and kinesins (Nonaka et al., 1998; Supp et al., 1997) in LR patterning, we examined the interaction of the cytoskeleton with the H+/K+-ATPase (Fig. 3F-H). Consistent with earlier observations linking embryo-wide asymmetry with subcellular organization (Bunney et al., 2003), and more recent work showing that H+/K+-ATPase subunits interact directly with the actin cytoskeleton (Chen et al., 2003; Lee et al., 1999; Vitavska et al., 2003), we found that the asymmetric targeting of the H+/K+-ATPase is dependent on actin along the LR axis, and on microtubules along the AV axis (Fig. 1). The ability of very early Latrunculin exposure to randomize LR asymmetry in embryos (Qiu et al., 2005) is consistent with its observed effects on the localization of proteins with roles in determining left-right asymmetry, linking cytoskeletal organization with large-scale asymmetry. We are currently investigating cytoskeletal structures that assure asymmetric localization of ion pumps. This model is in close agreement with early proposals by Corballis and Morgan that asymmetry is ultimately encoded in the spatial structure of the oocyte (Corballis and Morgan, 1978; Morgan and Corballis, 1978).

The polarization of the early cytoskeleton along the AV axis in Xenopus has been previously described (Gard, 1994; Gard, 1995; Gard et al., 1995; Pfeiffer and Gard, 1999; Roeder and Gard, 1994). Indeed, it has been implicated in the patterning of the DV axis in Xenopus (Ubbels et al., 1983), but no LR bias has been previously reported. Here, using a strategy developed by workers in Drosophila (Clark et al., 1994; Clark et al., 1997), we used motors directed to different ends of microtubules and fused to a chromogenic reporter as readout of native cytoskeletal orientation. Our data revealed novel and significant biases in microtubule organization in all three axes (Table 2c, Fig. 7A’), suggesting that the embryonic transport machinery is able to carry out much more subtle 3-dimensional localization than simply animal-vegetal targeting. This is illustrated strikingly in the precise, intracellular motions of the Kir4.1 protein resulting in “fingers”, “loops”, and triangular domains (Fig. 4D, 4G left red arrow).

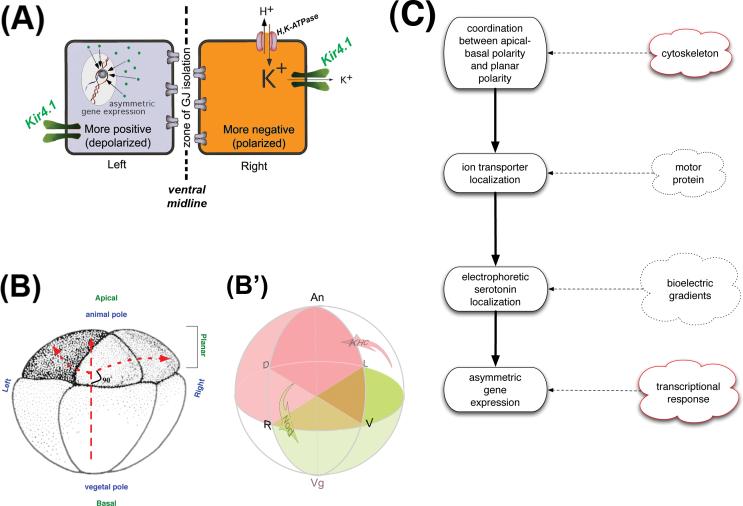

Figure 7. Synthesis of these data into a model of early events in LR patterning of Xenopus.

(A) Our current model, based on the results presented here implicating Kir4.1 function in LR patterning, is that symmetrical Kir4.1 presence in the ventral midline cells provides the controlled exit of excess K+ ions brought in by the H+/K+-ATPase on the right side. This allows the right cells to establish a pH and a membrane voltage that is different than that on the left side (Adams et al., 2006).

(B) The animal pole cells of the early Xenopus embryo are an epithelium that exhibits two polarities: the well-known apical-basal polarity along the animal-vegetal axis, and an orthogonal planar polarity along the LR/DV axes. Blue labels indicate embryonic axes, while green labels indicate polarity types. (B’) A 3-dimensional schematic illustrating the bias, linked in all 3 dimensions, conferred on motor proteins' cargo by the endogenous cytoskeleton orientation. The coordination of the LR axis with the other two is revealed both by the β-gal tracer data and the native localization of the H+/K+-ATPase proteins that are asymmetrically localized along 3 axes simultaneously. Arrows indicate the major bias of the two motors: KHC carries cargo to the right side of the animal half; Nod carries cargo to the ventral side of the vegetal half. Superimposed on the four cell stage embryo, this suggests that each of the four cells contains a different combination of cargoes: the right ventral cell receives both cargoes while the left dorsal cell receives neither; the left ventral cell receives only Nod cargo vegetally, while the right dorsal cell receives only KHC cargo animally.

(C) Taken together, these results can be integrated with previous data into a model whereby the events at fertilization and/or rotation set up cytoskeletal tracks whose polarization is coordinated along all three axes. This allows maternal proteins encoding ion transporters such as the H+/K+-ATPase to be precisely and asymmetrically localized, ultimately driving physiological asymmetries that feed into differential gene expression on the L and R sides.

Cytoplasmic rearrangements have been described in Xenopus (Danilchik and Denegre, 1991). Indeed, cytoplasmic flow is important in a variety of other cellular events, for example the patterning of the anterior-posterior axis in C. elegans. In this system, the asymmetric positioning of PAR proteins in the cortex of the egg prior to first cleavage is disrupted when a myosin II heavy chain protein is knocked-down. Notably, cytoplasmic flow is also disrupted, leading to the hypothesis that the asymmetric localization of proteins in anterior-posterior patterning in C. elegans occurs through cytoplasmic flows generated by the cytoskeleton and associated motors (Golden, 2000; Shelton et al., 1999). Interestingly, the “fountainhead effect” generated by cytoplasmic flows in the C. elegans embryo resembles the Kir4.1 pattern seen in Fig. 4H,N. Thus, it is possible that in early Xenopus embryos, much like in C. elegans, cytoskeletal architecture and associated molecular motors are utilized to create driving forces that lead to functionally critical asymmetric localization of patterning players.

Are these localizations due to targeted transport or to differential behavior of proteins in a bulk cytoplasmic flow? The differences between the patterns of Kir4.1 and H+/K+-ATPase (and the other early proteins described in Qiu et al., 2005) demonstrate that their targeting is not the result of a non-selective bulk movement of cytoplasm. It is possible however, that cytoplasmic rearrangements result in different localization due to differences in size, composition, or targeting sequences of vesicles carried by such flow. Such cytoplasmic rearrangements may be also blocked by cytoskeletal disruptors, thus contributing to protein mislocalization. Future work will be necessary to dissect the individual contributions of bulk cytoplasmic flows and directed targeting for these and other ion transporters. However, inhibition of dynein or myosin function (Fig. 4L,N) also results in distinct mislocalization of two different proteins, demonstrating differential involvement of motor protein activity in this process (consistent with prior data on early Xenopus dynein and kinesin (Qiu et al., 2005)). Because cytoplasmic flow also requires dynein, myosin, and cytoskeletal organization, and because several different proteins end up in different locations, the distinction between bulk flow and directed transport is not a sharp one, and the targeting may be achieved by a combination of bulk flows and oriented transport cues such as cytoskeleton.

We have not yet demonstrated direct interaction between motor protein complexes and the Kir4.1 or H+/K+-ATPase cargo. While no molecular loss-of-function data on Xenopus kinesin or dynein are available, both of these classes of motors have been functionally implicated in LR asymmetry (Marszalek et al., 1999; Nonaka et al., 1998; Supp et al., 1999), as has myosin (Hozumi et al., 2006; Speder et al., 2006; Speder and Noselli, 2007). We favor a model where these localization patterns result from a versatile and highly-regulated combination of long-range transport due to microtubules and anchoring via the actin cytoskeleton; Kir4.1, like the H+/K+-ATPase, is known to interact directly with the cytoskeleton (Guadagno and Moukhles, 2004), and indeed this system is likely to contain a feed-back loop since some ion exchangers (such as the NHE) are now known to themselves anchor cytoskeleton elements (Baumgartner et al., 2004; Corstens et al., 2003; Denker and Barber, 2002a; Denker and Barber, 2002b; Duncan and Warrior, 2002). An important future area of inquiry is the identification of structural (or sequence) elements in these ion transporters that may confer targeting to specific and different subcellular locales, since such elements must be important whether the localization is mediated by differential bulk flow or by targeted motor-protein-directed mechanisms.

Our data involved only two motors from the kinesin family; it is very likely that similar investigations using myosins, dyneins, and other kinesins will reveal an extremely rich set of targeting “zipcodes”. This is made even more likely by the striking fact that the paths preferred by the “+”-seeking KHC motor and the “-“-seeking NOD motor are not simple inverses of each other (Table 1C, Fig. 7B’). Thus, additional “modifiers” of directionality besides the simple orientation of the microtubule must exist, and may underlie numerous and complex localization paths. The above functional approach with motor-reporter fusion proteins could reveal subtle biases in directionality that may not be apparent by ultrastructure analysis of cytoskeleton. This study also reveals a new set of potentially useful molecular tools. Much like ER- and nuclear-targeting sequences, the NOD and KHC domains form the beginnings of a molecular toolkit that developmental biologists can fuse onto proteins of interest to drive their localization to specific components of the early embryo even when mRNA is injected at the 1 cell stage. It should be noted that these data do not directly implicate motor proteins in asymmetric localization of LR-relevant cargo (although this is supported by our previous work showing asymmetric localization of left-right dynein and Kif3B (Qiu et al., 2005), and by mouse data implicating these two motors in LR patterning (Nonaka et al., 1998; Supp et al., 1997)). What the data do show is that the very early embryo contains sufficient cues to enable motor proteins to localize along all three axes, demonstrating the concordant cellular polarity linking the LR axis to the other two axes (the movement of each transporter is along at least 2 orthogonal axes – not just on one, Fig. 7B’). The ideal candidate for these cues is the cytoskeleton (Abe et al., 2004; Qiu et al., 2005), although the molecular nature of the component physically linking the polarized cytoskeletal elements to their cargo is still unknown.

Our data support a Cartesian coordinate model, with asymmetric transport along 3 orthogonal axes directing kinesin-related motor protein movement. Such axes could be set up by a set of intracellular orthogonal cytoskeletal organizing structures such as the perpendicular centrioles (Beisson and Jerka-Dziadosz, 1999; Ubbels et al., 1983); these would be an ideal candidate for a nucleation center playing the role of Wolpert and Brown's “F-molecule” (Brown and Wolpert, 1990) that ultimately determines asymmetric localization of LR-relevant components such as the H+/K+-ATPase. However, recent data uncovered the existence of a rotational coordinate system based on an “East-West” chiral actin organization (Danilchik et al., 2006), and indeed myosin has been implicated in Drosophila asymmetry (Hozumi et al., 2006; Speder et al., 2006; Speder and Noselli, 2007). Future efforts must address the cooperation between these two systems and the roles of myosin, dynein, and kinesins in the patterning of the very early embryo. One possibility is that the East-West chirality in the radially-symmetrical egg is converted to a LR asymmetry by fertilization, since the definition of the dorso-ventral plane by sperm entry enables the embryo to set up orthogonal axes.

Where does H+/K+-ATPase/Kir4.1 localization fit into the LR pathway?

Our previous screen suggested a role for some K+ channel (Levin et al., 2002) in early LR patterning. Here, we present data suggesting Kir4.1 is that channel, since it is both necessary (Table 2) and sufficient (Levin et al., 2002) to affect asymmetry. The specific randomization caused by a dominant negative Kir4.1 construct reveals that Kir4.1 is required for LR patterning (unlike Kir2.1 and a variety of other transporters ruled out by pharmacological and genetic approaches). However, our data do not rule out possible involvement of additional potassium channels, and indeed Kir4.1 may cooperate with additional K+ conductances by oligomerization with other members of the inward rectifier family (Konstas et al., 2003; Pessia et al., 1996). It is possible that additional potassium channels participate in this function, and partially compensate for the loss of function of Kir4.1. While the Kir4.1 channel may be necessary for asymmetry, it is not itself asymmetrically localized. This is still consistent with our hypothesis because it is the H+/K+-ATPase that confers the asymmetry in this system. We propose that Kir4.1 allows the exit of excess potassium ions brought in by the H+/K+-ATPase, thus allowing this electroneutral antiporter to contribute to the observed membrane voltage differences developed in the L vs. R ventral cells by differential exchange with the external milieu (Adams et al., 2006; Levin et al., 2002). Indeed Kir4.1 plays the same role in another system – the mammalian ear, where Kir4.1 is involved in control of endocochlear potential (Hibino et al., 1997).

Our model (Fig. 7A) parallels the situation in neurons, where the closely related P-type pump Na+/K+-ATPase builds up high potassium, and K+ channels allow K+ to leave, generating a negative Vmem. Indeed, in fish, the Na+/K+-ATPase does participate in determination of heart laterality (Shu et al., 2003; Shu et al., 2007). Interestingly, the neuron's generation of membrane voltage gradients is assisted because the Na,K-ATPase is itself electrogenic (moving an unequal number of positive charges in vs. out of the membrane). Since the Xenopus H+/K+-ATPase is electroneutral by itself, this may explain why the embryo possesses an active V-type pump (V-ATPase) that extrudes positive charges from the right ventral cell (Adams et al., 2006) to assist the H+/K+-ATPase-Kir4.1 mechanism in generating a membrane voltage difference. While Kir4.1 represents an ideal candidate for this role in Xenopus, we are also currently pursuing the roles of another candidate, the KvLQT-1 channel, which also functions in concert with H+/K+-ATPase in a variety of mammalian tissues (Dedek, 2001; Geibel, 2005; Lambrecht et al., 2005; Wangemann, 2002).

How do these voltage asymmetries control downstream components of the LR pathway? One possible mechanism mediating between these ion fluxes and essential later asymmetric gene cascades is Ca++ signaling (McGrath et al., 2003; Raya and Belmonte, 2004), since voltage-gated calcium channels are a classical mechanism for transducing membrane voltage changes into 2nd messenger cascades that control downstream transcriptional changes (Libbus and Rosenbaum, 2002; Rosen et al., 1994; Trollinger et al., 2002). In chick, the appearance of asymmetric calcium at the node is regulated by the H+/K+-ATPase (Raya et al., 2004), and Ca++ channels have been implicated in mouse (Pennekamp et al., 2002) and zebrafish (Sarmah et al., 2005) asymmetry. However, prior data suggest that the roles of calcium in Xenopus asymmetry are likely to occur much later than the events we describe in the early embryo (Toyoizumi et al., 1997). Another likely possibility is that the H+/K+-ATPase/Kir4.1 component in Xenopus is a key aspect of the machinery that sets up the voltage gradients powering LR-asymmetric serotonin transport at later stages (Esser et al., 2006; Fukumoto et al., 2005a; Fukumoto et al., 2005b; Levin et al., 2006).

How conserved is this system across phyla?

Although the role of Kir4.1 remains to be examined in other model systems, the H+/K+-ATPase system has now been implicated in LR asymmetry in chick (Levin et al., 2002), zebrafish (Kawakami et al., 2005), sea urchin (Duboc et al., 2005; Hibino et al., 2006), and Ciona (Shimeld and Levin, 2006). The conservation of this system to mammalian development is unclear. None of the existing genetic data in the mouse system have yet revealed an asymmetry phenotype for either gene in mammals (Judd et al., 2005; Meneton et al., 1998; Spicer et al., 2000). This parallels the situation for gap junctions and elements of serotonergic signaling, and may reveal lack of conservation of the physiological LR mechanisms to the unique gastrulation mode of rodents. Since numerous members of any given ion transporter family usually exist in mice and are expressed in overlapping domains, single knockouts may fail to reveal LR phenotypes because of compensation/redundancy effects. This is one reason why inhibitor screens (Adams and Levin, 2006b; Adams and Levin, 2006c) have been successful – because reagents can be used to block all members of a given channel subtype. Until the relevant dominant-negative knock-ins are performed in mice, in a spatio-temporal (inducible) manner that allows survival (Sun-Wada et al., 2000), the relevance of the ion transporters in mouse asymmetry will remain open. Moreover, it is possible that a different kind of ion transporter is used in mice for the same physiological role, since a particular biophysical cell state can be established by a number of endogenous transporters. For example, the K+ ion is used differently in different systems for very basic cellular functions (Brachet and Alexandre, 1978): the ionophore valinomycin quickly arrests sea urchin and mouse eggs, but does not arrest Xenopus or Axolotl eggs until gastrulation. The relevant transporter classes remain to be thus tested in a mammalian laterality assay.

It is also possible that the reason that mouse knockouts for some of the early molecular components described above do not exhibit LR defects is that it is the maternal components that matter, as in Xenopus, not the zygotic. Maternal patterning effects in mice are often discounted (but see (Mager et al., 2006)), but it has been demonstrated that it is maternal serotonin that is crucial for development (Cote et al., 2007). Thus, the correct test of the conservation of these mechanisms to rodents and other mammals would require probing maternal contributions, not just zygotic knockouts. Thus, the question of conservation with respect to LR roles of these ion transporters is still open (Levin, 2006; Levin and Palmer, 2007; Speder and Noselli, 2007). Regardless of conservation to other species, our data reinforce the observation that the early frog embryo knows left from right within 1.5 hours of fertilization – long before the development of cilia-dependent mechanisms (Schweickert et al., 2007; Tabin, 2006).

Cell polarity and the embryonic LR axis

We have previously suggested that there is a deep conservation of mechanisms between left-right and epithelial patterning, based on the way that these systems align morphological and physiological cell polarities using cytoskeletal transport machinery (Levin, 2006). The above data on reporter and native H+/K+-ATPase localization reinforces the idea that the early frog embryo animal pole cells are an epithelium that exhibits two polarities: the well-known apical-basal polarity along the blastomeres' animal-vegetal axis (Chalmers et al., 2003; Fesenko et al., 2000; Muller and Hausen, 1995), and an orthogonal planar cell polarity (PCP) along the LR/DV axes (Fig. 7B) (Eaton and Simons, 1995). Transport along all 3 dimensions is linked (as is PCP to apical-basal polarity (Djiane et al., 2005; Eaton and Simons, 1995)), and consistent bias is conferred on motor proteins' cargo by the endogenous cytoskeleton orientation. A number of other parallels support this analogy. Just like H+/K+-ATPase and V-ATPase ion pumps in Xenopus asymmetry, frizzled and strabismus have to be recruited to the apical surface for planar polarity to organize (Zallen, 2007). Apical-basal polarity in epithelial cells depends on the cytoskeleton to direct ion transporter localization (Dunbar and Caplan, 2000; Dunbar and Caplan, 2001; Mense et al., 2000; Okamoto et al., 2002; Rizzolo, 1999). Wnt is involved in this coordination in early frog embryos (Kimelman and Pierce, 1996; Larabell et al., 1997; Laurent et al., 1997; Moon and Kimelman, 1998; Rowning et al., 1997; Schroeder et al., 1999; Weaver and Kimelman, 2004), as it is in planar cell polarity (Barrow, 2006; Colosimo and Tolwinski, 2006). Finally, 14−3−3 proteins are known to direct epithelial planar polarity (Benton et al., 2002; Hurd et al., 2003), and have recently been shown to be crucial for early embryonic LR asymmetry (Bunney et al., 2003). Based on these data, as well as the intriguing localization of both V-ATPase (Adams, et. al. 2006) and H+/K+-ATPase (Fig. 1G) in specific relation to the sperm entry point, it is tempting to speculate that the initial alignment of the LR axis takes place during the β-catenin-dependent rearrangements of the early cytoskeleton (including cortical rotation) that occur after sperm entry.

These observations further constrain the timing of the initial LR orientation event to about an hour after fertilization. Future work will molecularly dissect the cytoskeleton organizing machinery that links the apical-basal and planar polarity systems, thus forming an orthogonal 3-dimensional space for the orientation of early bioelectrical signals in left-right patterning.

Materials and methods

Animal husbandry

Xenopus embryos were collected according to standard protocols (Sive et al., 2000) in 0.1× Modified Marc's Ringers (MMR) pH 7.8 + 0.1% Gentamicin and staged according to (Nieuwkoop and Faber, 1967). Chick eggs were obtained from Charles River Labs and staged according to (Hamburger and Hamilton, 1992).

Chromogenic in situ hybridization

In situ hybridization was performed according as previously described, for frog (Harland, 1991) and chick (Nieto et al., 1996). Xenopus embryos were collected and fixed in MEMFA; chick embryos were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. Prior to in situ hybridization, embryos were washed in PBS + 0.1% Tween-20 and then transferred to methanol through a 25%/50%/75% series. Probes for in situ hybridization were generated in vitro from linearized templates using DIG labeling mix from Invitrogen. Chromogenic reaction times were optimized for signal : background ratio.

Xenopus Microinjection

For microinjections, capped, synthetic mRNAs (Sive et al., 2000) were dissolved in water and injected into embryos in 3% Ficoll using standard methods (100 msec pulses in each injected cell with borosilicate glass needles calibrated for a bubble pressure of 55−62 kPa in water). Injections delivered approximately 2.7 nL into each cell; to avoid bias in the subsequent localization analysis, mRNA injections were made equatorially or directly into the animal pole, respectively. After 30 minutes embryos were washed in 0.75× MMR for 30 minutes and cultured in 0.1× MMR until desired stages. Results of injections are reported as: % of otherwise normal embryos that were heterotaxic, sample size (N), and χ2 and p values comparing treated to controls (using Pearson correction). ER-Kir4.1 constructs were created by fusing the peptide sequence KHILFRRRRRGFRQ to the C terminus of Bir10 (Schwappach et al., 2000).

Immunohistochemistry

Frog embryos were fixed overnight in MEMFA and stored at 4 °C in PBTr (1× PBS + 0.1% Triton-100). They were embedded in gelatin/albumin medium, and sectioned at 40 μm on a Leica vibratome as previously described (Levin, 2004a). The sections were then washed 3× in PBTr, blocked with 10% goat serum, and incubated with primary antibody at 1:500 in PBTr overnight, washed 6× with PBTr, and incubated with an alkaline-phosphatase-conjugated secondary antibody overnight. After 6 washes in PBTr, detection was carried out using NBT and BCIP (X-Phos). Chromogenic reaction times were optimized for signal : noise ratio. Kir4.1 antibody (made to native rat sequence) used was Alomone labs #APC-035. Consensus patterns are reported for each plane of section and embryonic stage based on N>20. Chick embryos were processed in wholemount, embedded in JB4 (Polysciences), and sectioned at 10 μm.

Drug exposure

Cytoskeleton modulating compounds (Molecular Probes): the microtubule disruptor Nocodazole (Elinson and Rowning, 1988; Scharf et al., 1986) and the microfilament disruptor Latrunculin (Chartrain et al., 2006; Schatten et al., 1986) were used at 50 nM and 4 μM respectively. Inhibition of motor protein activity (SIGMA): the myosin II blocker Blebbistatin (Kovacs et al., 2004) and the dynein blocker erythro-9-[3-(2-Hydroxynonyl)]adenine (EHNA) (Beckerle and Porter, 1982; Penningroth et al., 1982) were used at 0.3 mM and 1 mM respectively.

Laterality assays

Xenopus embryos at st. 45 were analyzed for position (situs) of 3 organs: the heart, stomach, and gallbladder (Levin and Mercola, 1998a). Heterotaxia was defined as reversal in one or more organs. Only embryos with normal dorsoanterior development (DAI=5) were scored, thus avoiding confounding randomization caused by midline defects (Danos and Yost, 1996), and only clear left- or right-sided organs were scored; percent heterotaxia was calculated as number heterotaxic divided by the number of total scorable embryos, i.e. embryos normal in all other ways, with DAI=5. A χ2 test (with Pearson correction for increased stringency) was used to compare absolute counts of heterotaxic embryos; a contingency table with χ2 test (Kirkman, 2007) was used to compare outcomes of blastomere localization for the lacZ NOD/KHC constructs.

Western blotting

Twenty-five Xenopus embryos were resuspended in lysis buffer (1% Triton ×100, 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO4, 5 mM EDTA, 10 mM Tris pH 7.6, 2 mM PMSF). Protein solution was mixed at 1:1 with Laemmli sample buffer (Biorad) containing 2.5% 2-mercaptoethanol. The proteins were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and electrotransferred to a PVDF membrane. After washing, the membrane was blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin and 5% dry milk in tris-buffered saline including 0.1% Tween-20. It was then incubated overnight in a Mini-PROTEAN II multiscreen apparatus (Biorad) at 4 °C with the primary antibody, diluted in TTBS + 3% BSA + 5% dry milk (1:3000 for H+/K+-ATPase α). After washing, the blots were incubated with peroxidase-conjugated second antibody (1:5000) and developed using an ImmunoStar Chemiluminescent Protein Detection System (Biorad) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Table 1b. Lac-Z enzyme fused to motor proteins reveal endogenous polarity in cytoplasmic transport machinery. localization of motor proteins along animal-vegetal axis.

Embryos at the 1 cell stage received injection of the indicated mRNA directly into the animal pole of the 1 cell fertilized egg. After the embryos had reached 4-cell stage, those with obvious dorso-ventral orientation (based on blastomere shape and size) were fixed, developed for β-gal stain, and thick-sectioned along the animal-vegetal axis. Sections were then examined for the presence of blue lac-Z signal in animal vs. vegetal pole. When β-gal alone was injected, most of the embryos exhibited animal-pole staining (Fig. 2E,E’) while 20% exhibited vegetal-pole stain. When mRNA was injected encoding the Nod domain fused to β-gal, the stain was almost always observed in the vegetal pole (Fig. 2F,F’). When KHC+β-gal mRNA was injected, almost all of the sections exhibited animal pole staining. Statistics: Nod localizes to the vegetal pole while KHC and control staining is seen in the animal pole (χ2 = 37.1; p<0.001).

| Construct: | Animal pole | Vegetal pole | Both | Total (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control β-gal | 31 | 0 | 8 | 39 |

| Nod+β-gal | 1 | 54 | 2 | 57 |

| KHC+β-gal | 56 | 0 | 1 | 57 |

Table 1c.

Lac-Z enzyme fused to motor proteins reveal endogenous polarity in cytoplasmic transport machinery. a summary of the cytoskeletal directionality detected in the early embryo

| Entity | AV axis | LR axis | DV axis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plain mRNA | Weak Animal | − | − |

| Kinesin KHC motor (+ end of microtubules) | Strong Animal | Strong Right | Weak Ventral |

| Kinesin NOD motor (- end of microtubules) | Strong Vegetal | − | Strong Ventral |

Table 1d.

Lac-Z enzyme fused to motor proteins reveal endogenous polarity in cytoplasmic transport machinery. a summary of the localization patterns of proteins in the early frog embryo

| Entity | AV axis | LR axis | DV axis |

|---|---|---|---|

| H+/K+-ATPase α | Strong Animal | Strong Right | Strong Ventral |

| Kir4.1 | Strong Animal, Finger-like projections | Symmetric | Weak Ventral |

Acknowledgements

We thank Punita Koustubhan and Katherine Gallant for Xenopus husbandry and general lab assistance, Ira Clark for the original PNOD and PKHC plasmids, and William Bement and David Gard for useful discussions about early Xenopus cytoskeleton/motor proteins. D. John Adelman (OHSU) provided a Bir10 (Kir4.1) plasmid, and Käthi Geering provided H,K-ATPase antibodies. This work was supported by NHTSA DTNH22-06-G-00001, NIH GM-067227 and GM07742, March of Dimes #6-FY04−65, and American Heart Association Established Investigator Grant #0740088N grants to M.L., NIH 1K22-DE016633 grant to D.S.A., and the A*STAR overseas National Science Scholarship from the Agency for Science and Technology (Singapore) to S.A. Part of this investigation was conducted in a Forsyth Institute facility renovated with support from Research Facilities Improvement Grant Number CO6RR11244 from the National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abe T, Thitamadee S, Hashimoto T. Microtubule defects and cell morphogenesis in the lefty1lefty2 tubulin mutant of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2004;45:211–20. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pch026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams D, Levin M. Inverse Drug Screens: a rapid and inexpensive method for implicating molecular targets. 2006a. Genesis in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Adams DS, Levin M. Inverse drug screens: a rapid and inexpensive method for implicating molecular targets. Genesis. 2006b;44:530–40. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams DS, Levin M. Strategies and techniques for investigation of biophysical signals in patterning. In: Whitman M, Sater AK, editors. Analysis of Growth Factor Signaling in Embryos. Taylor and Francis Books; 2006c. pp. 177–262. [Google Scholar]

- Adams DS, Robinson KR, Fukumoto T, Yuan S, Albertson RC, Yelick P, Kuo L, McSweeney M, Levin M. Early, H+-V-ATPase-dependent proton flux is necessary for consistent left-right patterning of non-mammalian vertebrates. Development. 2006;133:1657–1671. doi: 10.1242/dev.02341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrow JR. Wnt/PCP signaling: a veritable polar star in establishing patterns of polarity in embryonic tissues. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2006;17:185–93. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner M, Patel H, Barber DL. Na(+)/H(+) exchanger NHE1 as plasma membrane scaffold in the assembly of signaling complexes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;287:C844–50. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00094.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckerle MC, Porter KR. Inhibitors of dynein activity block intracellular transport in erythrophores. Nature. 1982;295:701–3. doi: 10.1038/295701a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beisson J, Jerka-Dziadosz M. Polarities of the centriolar structure: morphogenetic consequences. Biol Cell. 1999;91:367–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benton R, Palacios IM, St Johnston D. Drosophila 14−3−3/PAR-5 is an essential mediator of PAR-1 function in axis formation. Dev Cell. 2002;3:659–71. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00320-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black SD, Vincent JP. The first cleavage plane and the embryonic axis are determined by separate mechanisms in Xenopus laevis. II. Experimental dissociation by lateral compression of the egg. Developmental Biology. 1988;128:65–71. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(88)90267-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brachet J, Alexandre H. [Effect of valinomycin on mitotic activity and ciliary movement during embryonic development]. C R Acad Sci Hebd Seances Acad Sci D. 1978;286:895–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown N, Wolpert L. The development of handedness in left/right asymmetry. Development. 1990;109:1–9. doi: 10.1242/dev.109.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunney TD, De Boer AH, Levin M. Fusicoccin signaling reveals 14−3−3 protein function as a novel step in left-right patterning during amphibian embryogenesis. Development. 2003;130:4847–4858. doi: 10.1242/dev.00698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burdine R, Schier A. Conserved and divergent mechanisms in left-right axis formation. Genes & Development. 2000;14:763–776. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burn J. Disturbance of morphological laterality in humans. CIBA Found Symp. 1991;162:282–296. doi: 10.1002/9780470514160.ch16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey B. Two rights make a wrong: human left-right malformations. Human Molecular Genetics. 1998;7:1565–71. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.10.1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]