Abstract

Maribavir, an oral antiviral drug with activity against cytomegalovirus, is currently undergoing studies to assess its efficacy and safety as cytomegalovirus prophylaxis following stem cell or solid organ transplantation. The main objective of this study was to assess the effects of oral ketoconazole, a potent inhibitor of the cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4) isoenzyme, on the pharmacokinetics of maribavir. This was an open-label crossover study with 20 healthy adults. Subjects were administered a single dose of maribavir at 400 mg. After a washout period, subjects received a single dose of ketoconazole at 400 mg followed by a single dose of maribavir. Blood samples were collected for each drug sequence, and pharmacokinetic parameters for maribavir and its principal metabolite, VP 44469, were determined. Safety was evaluated by physical examination, clinical laboratory testing, 12-lead electrocardiogram, and monitoring for adverse events. Ketoconazole moderately reduced the clearance of both maribavir and VP 44469; oral clearance values were 35% and 13% lower, respectively, for maribavir-plus-ketoconazole treatment than for maribavir alone. Based on the assumption of complete inhibition of CYP3A4 activity, CYP3A4 is responsible for 35% of the overall clearance of maribavir. Treatment was generally well tolerated. The most-common adverse event was dysgeusia (taste disturbance), reported by nine (47%) and seven (35%) subjects in the maribavir alone and maribavir-plus-ketoconazole groups, respectively. The pharmacokinetic findings, in combination with the acceptable tolerability within the maribavir and maribavir-plus-ketoconazole treatment groups, suggest that no dose adjustment of maribavir is necessary when coadministered with CYP3A4 inhibitors or substrates.

Maribavir is an oral antiviral drug with activity against cytomegalovirus (CMV) that has a favorable preclinical (5, 6) and early clinical (9, 15, 16) efficacy and safety profile. Maribavir is currently undergoing phase III studies to assess its efficacy and safety as CMV prophylaxis following allogeneic stem cell or solid organ transplantation. Maribavir is a benzimidazole l-riboside compound that has a unique mechanism of action in that it inhibits UL97 kinase activity, which reduces both viral DNA assembly and egress of viral capsids from the nucleus of CMV-infected cells (3, 7, 8). Maribavir has demonstrated good in vitro activity against CMV isolates or strains that are resistant to current CMV drugs (ganciclovir, foscarnet, and cidofovir) (1, 2).

In pharmacokinetic studies, maribavir was rapidly and reasonably well absorbed, with a bioavailability of at least 30% to 40% (15). Mean peak plasma concentrations were largely dose proportional and were achieved between 1 and 3 h after administration in healthy individuals and in patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection (9, 15). Maribavir has a mean terminal elimination half-life (t1/2) of approximately 5 h in plasma, and based on studies in animals, maribavir is eliminated mainly by biliary excretion (10, 15). This is consistent with recent data showing that maribavir pharmacokinetics are similar in healthy volunteers and in those with renal impairment (14).

Maribavir also undergoes extensive metabolism. In healthy and HIV-infected subjects, <2% of the dose is excreted unchanged in the urine (10, 15). The predominant metabolite in urine is VP 44469 (10). This inactive N-dealkylated metabolite is mainly formed by cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4) (15).

Knowledge of the metabolic route of elimination of maribavir is useful for predicting potential interactions with coadministered drugs. Findings from a study with healthy volunteers given a mixture of markers for CYP enzyme activity indicate that maribavir does not affect CYP1A2, CYP2C9, or CYP3A isoenzyme activity but may inhibit CYP2C19 and CYP2D6 activity (11). Although maribavir was shown not to affect CYP3A4 isoenzyme activity, it is unknown what effect compounds that inhibit this isozyme have on the pharmacokinetics of maribavir. The main objective of this study was to assess the effects of oral ketoconazole, a potent inhibitor of the CYP3A4 isoenzyme, on the pharmacokinetics of maribavir.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects.

Men or women between the ages of 18 and 50 years were eligible for enrollment. Subjects were required to be nonsmokers and otherwise healthy as determined by medical history, physical examination, laboratory results, vital signs, and 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG). Women of childbearing potential were to follow an acceptable method of birth control. Subjects agreed not to take any prescription or nonprescription medications (including estrogen- and/or progestin-containing products, histamine antagonists, proton pump inhibitors, herbal preparations, or vitamins) or receive vaccinations during the course of the study. Subjects were instructed to refrain from consuming Seville oranges, grapefruits (including grapefruit juice), or alcoholic beverages during the study. They were also instructed not to drink or eat caffeine- and theobromine-containing beverages and foods for 24 h before or after dosing in each treatment period. All subjects provided written informed consent, and the study was approved by the institutional review board at the participating site.

Subjects were excluded from the study if they were pregnant or breast-feeding; chewed tobacco or used nicotine replacement devices within 6 months before the screening visit; required treatment for alcohol or illicit drug abuse within 2 years; had taken any prescription or nonprescription drugs during the 3 months before the screening visit; had received an immunization during the 2 weeks before the screening visit; had a known intolerance to ketoconazole; had known liver disease (e.g., hepatitis B or hepatitis C); had elevated aspartate aminotransferase or alanine aminotransferase levels at the time of screening; had known immune deficiency disease or were HIV positive; had participated in any other investigational drug study within 30 days of the screening visit; or had participated in any previous maribavir clinical trial.

Study design.

This was an open-label, random-sequence, two-way crossover study conducted from 16 November 2004 to 4 January 2005. To achieve a target of 16 subjects who completed the study, 20 adults (10 men and 10 women) were enrolled at the Baltimore Clinical Pharmacology Research Unit and were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive one of two sequences (5 men and 5 women per sequence) of maribavir alone and ketoconazole plus maribavir. For sequence 1, treatment period 1, single-dose maribavir at 400 mg (four 100-mg tablets; ViroPharma Incorporated, Exton, PA) was administered on day 1, followed by a full pharmacokinetic profile assessment over 24 h. After a 1-week washout period, treatment period 2 consisted of a single dose of ketoconazole at 400 mg (two 200-mg tablets; Janssen Pharmaceutica, Titusville, NJ) administered on day 8, followed 1 h later by a single dose of maribavir at 400 mg and subsequently another full pharmacokinetic profile assessment over 24 h. The order of the two treatments was reversed in sequence 2. Subjects fasted overnight on the day before drug administration in each treatment period and continued to fast for 4 h after the maribavir dose in each treatment period. All study drug doses were administered under the supervision of study personnel.

Sample collection and analysis.

For each sequence, blood samples for determination of maribavir and VP 44469 plasma concentrations (separate samples for each) were collected just before the maribavir dose and then 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 12, 16, and 24 h after the dose. A 24-hour urine sample was collected on day 1 and day 8 of each sequence for determination of maribavir and VP 44469 concentrations. Urine collection began with the first voided specimen following administration of maribavir, and the final specimen was collected at the end of the 24-hour period on each day. Blood samples for the determination of ketoconazole plasma concentrations were collected 2 and 24 h after the ketoconazole dose in both sequences, and an additional sample was collected before the dose of maribavir in sequence 2 (trough value).

Plasma and urine assays for maribavir and VP 44469 and plasma assays for ketoconazole were performed by Tandem Laboratories (Salt Lake City, UT) using validated tandem liquid chromatography and mass spectrometric detection methods. Plasma and urine samples of maribavir and VP 44469 were processed by solid-phase extraction. The validated calibration range in plasma was 5 to 1,000 ng/ml for maribavir and VP 44469; the accuracy (percent bias) and precision (coefficient of variation) based on quality control samples for each analyte were ≤5.3% and ≤9.1%, respectively. In urine, the calibration range for maribavir and VP 44469 was 50 to 10,000 ng/ml, with an accuracy of ≤9.3% and a precision of ≤11.3%. Ketoconazole samples were prepared by automated protein precipitation extraction. The validated calibration range was 50 to 5,000 ng/ml; accuracy was ≤9.3%.

Pharmacokinetic endpoints and analyses.

The primary pharmacokinetic parameters determined were area under the plasma concentration versus time curve (AUC0-t and AUC0-∞), maximum plasma concentration (Cmax), time to Cmax (tmax), terminal elimination rate constant (λz), t1/2, oral clearance (CL/F), terminal phase volume of distribution/bioavailability (Vz/F), amount excreted in urine (Ae), and renal clearance (CLR). The AUC0-t was calculated as the AUC from time zero to the time of the last measurable concentration, calculated by the log-linear trapezoidal method. The AUC0-∞ was calculated as the sum of AUC0-t plus the ratio of the last measurable plasma concentration to the λz. Oral clearance was calculated as dose/AUC0-∞. The λz was calculated by linear regression of concentration values in the apparent log-linear terminal elimination phase. The t1/2 was calculated as 0.693/λz, the Vz/F as dose/(λz × AUC0-∞), and CLR as Ae/AUC0-24. Nominal sampling times were used in the calculations, and WinNonlin Professional (version 2.1; Pharsight Corporation, Cary, NC) was used for the pharmacokinetic analyses.

Safety assessments and endpoints.

Safety was evaluated by physical examination, clinical laboratory testing (hematology, clinical chemistry, and urinalysis), vital sign measurement, 12-lead ECG, and monitoring for adverse events. Clinical laboratory testing was performed on the day before dosing and the day after dosing in both sequences. Liver function tests were performed at the 15-day follow-up visit. ECGs were performed on the day before dosing for treatment period 1 and at 2 and 4 h after dosing. ECG data included PR, QRS, QT, and QTc intervals and heart rate. All adverse events were recorded by the study investigator, who also assessed the severity and potential relationship to the study drug for each event.

Statistical analyses.

Based on an intrasubject coefficient of variation of 35%, a total of 16 subjects would have 90% power to show that the 90% confidence interval (CI) of the ratio of the geometric mean of the two treatment groups was within a range of 0.7 to 1.43. The data analysis for pharmacokinetics and safety was generated using SAS/STAT software, version 8, of the SAS System for Windows (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Data underwent natural logarithmic transformation before the analysis. An analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted on all parameters (except tmax) for a two-period crossover design fitting the terms for treatment, sequence, and subject within sequence. The ranked values of tmax were analyzed with the ANOVA model. Estimates were calculated for the difference between the treatment least-squares means and their standard errors. These results were retransformed using antilogarithms to obtain the ratio of geometric means for maribavir plus ketoconazole to those for maribavir alone. Adverse events were summarized based on their incidence rates; no statistical analyses were performed.

RESULTS

Patient disposition and demographics.

Of the 20 subjects enrolled, 19 (95%) completed the study. One patient withdrew from the study after experiencing an adverse event (vomiting). Demographics for the 20 enrolled subjects are provided in Table 1. The mean age of the subjects was 30 years, and 50% were men.

TABLE 1.

Subject demographics

| Characteristic | Value for all enrolled subjects (n = 20) |

|---|---|

| Mean age [yr (SD)] | 30 (9.3) |

| Men [n (%)] | 10 (50) |

| Mean wt [kg (SD)] | |

| Men | 80 (12.5) |

| Women | 71 (17.0) |

| Race [n (%)] | |

| White | 9 (45) |

| Black | 11 (55) |

Pharmacokinetics.

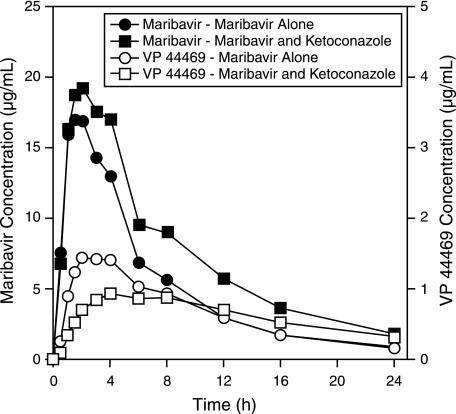

Mean ± standard deviation plasma concentrations of ketoconazole at 2 and 24 h after 400-mg ketoconazole administration were 6,149 ± 2,423 and 111 ± 122 ng/ml, respectively. These values were comparable to those reported elsewhere in healthy volunteers (4). Plots for the mean plasma maribavir and VP 44469 concentrations over time are shown in Fig. 1. Mean maribavir plasma concentrations over time were higher with concomitant ketoconazole administration than with maribavir alone. Mean VP 44469 plasma concentrations following concomitant ketoconazole administration were lower for the initial 8 h and higher after 12 to 24 h than with maribavir alone.

FIG. 1.

Mean plasma maribavir and VP 44469 concentration-time profiles following oral administration of maribavir alone and maribavir plus ketoconazole.

Summaries of pharmacokinetic results for maribavir and VP 44469 are presented in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. Values for maribavir Cmax, AUC, Ae, and t1/2 were higher, and CL/F values were lower, for maribavir plus ketoconazole than for maribavir alone (Table 2). The test for treatment effects for tmax was not statistically significant (P = 0.536). The CL/F value, based on the ratio of geometric means, was 35% lower for maribavir-plus-ketoconazole treatment than for maribavir alone.

TABLE 2.

Summary of maribavir pharmacokinetic parameters

| Parametera | Value for:

|

Ratio of geometric means (95% CI)c | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maribavir alone [mean (SD)] | Maribavir + ketoconazole [mean (SD)] | ||

| tmax (h) | 1.7 (0.8) | 1.9 (0.9) | Not differentb |

| Cmax (μg/ml) | 19.8 (3.9) | 21.8 (4.4) | 1.10 (1.01-1.19) |

| λz (1/h) | 0.132 (0.042) | 0.110 (0.036) | 0.83 (0.78-0.88) |

| t1/2 (h) | 5.73 (1.78) | 6.88 (1.99) | 1.20 (1.13-1.28) |

| AUC0-t (μg·h/ml) | 119 (36) | 173 (50) | 1.46 (1.38-1.55) |

| AUC0-∞ (μg·h/ml) | 126 (41) | 194 (64) | 1.53 (1.44-1.63) |

| Vz/F (liters) | 27.5 (7.6) | 21.6 (6.6) | 0.78 (0.73-0.84) |

| CL/F (liters/h) | 3.56 (1.30) | 2.32 (0.85) | 0.65 (0.61-0.69) |

| Ae (mg) | 4.12 (1.47) | 9.86 (3.97) | 2.38 (1.99-2.84) |

| CLR (ml/h) | 57.2 (18.5) | 24.98 (9.49) | 1.63 (1.36-1.94) |

λz, terminal elimination rate constant; Ae, amount excreted in urine; AUC0-t and AUC0-∞, area under the plasma concentration versus time curve from time zero to the time of the last measurable concentration (t) and to infinity (∞); CI, confidence interval; CLR, renal clearance; Cmax, maximum plasma concentration; CL/F, oral clearance; t1/2, terminal elimination half-life; tmax, time to Cmax; Vz/F, terminal phase volume of distribution/bioavailability.

Ranked values of tmax were analyzed with the ANOVA model (P = 0.5364).

Maribavir plus ketoconazole/maribavir alone.

TABLE 3.

Summary of VP 44469 pharmacokinetic parameters

| Parametera | Value for:

|

Ratio of geometric means (95% CI)c | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maribavir alone [mean (SD)] | Maribavir + ketoconazole [mean (SD)] | ||

| tmax (h) | 2.5 (0.9) | 5.5 (2.7) | Differentb |

| Cmax (μg/ml) | 1.6 (0.4) | 1.0 (0.5) | 0.60 (0.55-0.66) |

| λz (1/h) | 0.109 (0.031) | 0.071 (0.030) | 0.62 (0.55-0.70) |

| t1/2 (h) | 6.83 (1.7) | 11.8 (5.5) | 1.62 (1.43-1.84) |

| AUC0-t (μg·h/ml) | 15.6 (3.2) | 14.7 (4.1) | 0.93 (0.87-0.99) |

| AUC0-∞ (μg·h/ml) | 17.4 (3.5) | 20.5 (5.5) | 1.15 (1.08-1.23) |

| Vz/F (liters) | 235 (78) | 342 (141) | 1.40 (1.26-1.56) |

| CL/F (liters/h) | 23.8 (4.6) | 21.1 (6.4) | 0.87 (0.81-0.92) |

| Ae (mg) | 110 (40) | 95 (32) | 0.85 (0.62-1.15) |

| CLR (ml/h) | 7,637 (3,723) | 6,876 (3,105) | 0.91 (0.68-1.22) |

λz, terminal elimination rate constant; Ae, amount excreted in urine; AUC0-t and AUC0-∞, area under the plasma concentration versus time curve from time zero to the time of the last measurable concentration (t) and to infinity (∞); CI, confidence interval; CLR, renal clearance; Cmax, maximum plasma concentration; CL/F, oral clearance; t1/2, terminal elimination half-life; tmax, time to Cmax; Vz/F, terminal phase volume of distribution/bioavailability.

Ranked values of tmax were analyzed with the ANOVA model (P < 0.001).

Maribavir plus ketoconazole/maribavir alone.

Similarly, VP 44469 Cmax and λz were lower, and t1/2 values were higher, for maribavir plus ketoconazole than for maribavir alone (Table 3). The test for treatment effects for tmax was statistically significant (P < 0.001). Mean tmax values for VP 44469 were 2.5 h for maribavir alone and 5.5 h for maribavir plus ketoconazole. Consistent with the concentration-time profile, AUC values were similar between treatments (Fig. 1). Results for the ratio of geometric means of treatments indicated that λz for VP 44469 was 38% lower for maribavir-plus-ketoconazole treatment than for maribavir alone.

Adverse events.

Maribavir treatment was generally well tolerated (Table 4). With the exception of a report of a headache of moderate intensity, adverse events were of mild intensity. One subject was withdrawn from the study after experiencing vomiting after receiving a single dose of ketoconazole at 400 mg and a single dose of maribavir at 400 mg (sequence 2, treatment period 1).

TABLE 4.

Summary of adverse events for all treated subjects

| Adverse event | Incidence [n (%)] with treatment of:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maribavir alone (n = 19)

|

Maribavir + ketoconazole (n = 20)

|

|||

| All | Treatment relateda | All | Treatment relateda | |

| Dysgeusia | 9 (47) | 9 (47) | 7 (35) | 7 (35) |

| Abdominal pain | 1 (5) | 0 | 1 (5) | 0 |

| Headache | 0 | 0 | 2 (10) | 2 (10) |

| Anemia | 1 (5) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Catheter site edema | 1 (5) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Furuncle | 1 (5) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nausea | 0 | 0 | 1 (5) | 0 |

| Genital pruritus, female | 1 (11) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Vomiting | 0 | 0 | 1 (5) | 1 (5) |

| Subjects with ≥1 adverse event | 12 (63) | 9 (47) | 10 (50) | 9 (45) |

Treatment related: possibly, probably, or definitely related to study drug, as determined by the investigator.

The most-common adverse event was dysgeusia (taste disturbance), reported by nine (47%) and seven (35%) subjects in the maribavir-alone and maribavir-plus-ketoconazole groups, respectively. The onset of dysgeusia was generally within 1 h after dosing, with variable duration (3 min to 23 h), and it was most commonly described as a metallic taste. All events of dysgeusia were considered by the investigator to be of mild intensity and resolved without therapy. Twelve (60%) subjects reported adverse events that the investigator considered to be possibly related to ketoconazole (16 events total) during the maribavir-plus-ketoconazole treatment period. The events included dysgeusia (n = 9), nausea (n = 3), headache (n = 2), abdominal pain (n = 1), and vomiting (n = 1).

No patient had ECG findings that the investigator considered clinically significant at any point during the study. Clinical laboratory, urinalysis, and vital sign evaluations were generally unremarkable. Three subjects had at least one new-onset clinical laboratory value that met a prespecified level of clinical significance: one elevated total bilirubin level (considered related to sample hemolysis), one elevated eosinophil count (10.2%, in a subject whose baseline value was 9.3%), and one decreased hemoglobin/hematocrit value. Overall, there were no trends suggesting laboratory toxicities associated with maribavir in this study.

DISCUSSION

This open-label crossover study assessed the effects of ketoconazole on maribavir pharmacokinetics in 19 healthy adults. The results demonstrated that ketoconazole moderately reduced the clearance of both maribavir and VP 44469, its principal metabolite. Based on the assumption that ketoconazole treatment completely inhibited CYP3A4 activity, these results indicate that CYP3A4 is responsible for 35% of the overall clearance of maribavir. The assumption of near-complete inhibition of CYP3A4 by ketoconazole is based on a study using midazolam, a drug metabolized exclusively by CYP3A4, in which ketoconazole reduced the oral clearance of midazolam to about 6% of the baseline value (13).

The effects of CYP3A4 inhibition on VP 44469 formation and clearance are less straightforward. The rate of VP 44469 formation is reduced secondary to CYP3A4 inhibition by ketoconazole as evidenced by lower VP 44469 concentrations during the first 8 h after maribavir-plus-ketoconazole administration. VP 44469 t1/2 was also increased, likely secondary to further metabolism via a pathway that may be subject to inhibition by ketoconazole. Although the t1/2 was increased, it was not accompanied by a significant increase in AUC, suggesting that the overall impact of inhibition of CYP3A4 on VP 44469 is offset by a decreased formation of VP 44469 and alternate pathways of maribavir elimination.

The results of this study also indicate that maribavir is reasonably well tolerated. With the exception of one moderate adverse event (headache), all reported adverse events were mild in intensity, with dysgeusia representing the majority of all adverse events. Vital signs, clinical laboratory tests, and ECG results were unremarkable and did not suggest any abnormalities associated with maribavir administration. These tolerability results are consistent with those observed in other clinical studies using single- or multiple-dose maribavir (11, 14, 15), in which dysgeusia was the most-notable adverse event. Taste disturbance was reported in 94% of healthy subjects receiving maribavir at 400 mg twice daily for 10 days (11). Similar findings were reported in subjects with renal impairment (14).

Determination of the contribution of CYP3A4 to the metabolism and clearance of maribavir is important because there are a number of potential interactions associated with drugs that inhibit this isoenzyme that may be administered concomitantly with maribavir (12). In addition to ketoconazole, examples of inhibitors of this enzyme include other azole antifungal drugs (itraconazole), calcium channel blockers (verapamil and diltiazem), most macrolide antibiotics, HIV protease inhibitors, and grapefruit juice (12). Substrates of this isoenzyme include alprazolam, cyclosporine, HIV protease inhibitors, tacrolimus, terfenadine, and calcium channel blockers (12). Despite near-complete inhibition of CYP3A4 metabolism with concomitant ketoconazole treatment in this study, there was only a moderate change in maribavir pharmacokinetics: the mean Cmax increased by 10% (95% CI, 1% to 19%), and the mean AUC0-t increased by 46% (95% CI, 38% to 55%). The CYP3A4 isoenzyme system is estimated to be responsible for approximately 35% of the overall clearance of maribavir. Furthermore, since renal excretion is not a major pathway of elimination, these findings suggest multiple metabolic pathways of elimination for maribavir. These pharmacokinetic findings, in combination with the tolerability in both the maribavir and maribavir-plus-ketoconazole treatment groups, suggest that no dose adjustment of maribavir is necessary when it is coadministered with CYP3A4 inhibitors or substrates.

A single oral dose of maribavir at 400 mg was generally well tolerated when administered with or without oral ketoconazole at 400 mg. An earlier study using much higher doses (up to 1,200 mg twice daily) demonstrated a good safety and tolerability profile, with dysgeusia as the most-common adverse event (82%) and diarrhea, nausea, and headache reported in ≤26% of maribavir-treated subjects (9). The observation that the CYP3A4 isoenzyme is responsible for only about one-third of the overall clearance of maribavir in addition to the established tolerability at higher doses suggest that there is no clinically significant impact on safety from a moderate decrease of elimination with CYP3A4 inhibition as seen in this study.

Acknowledgments

We thank Rick Davis for his assistance in drafting the manuscript.

This study was funded by ViroPharma Incorporated.

This work was conducted at one site: PAREXEL International, Baltimore Clinical Pharmacology Research Unit, Harbor Hospital Center, Baltimore, MD 21225.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 3 March 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Biron, K. K., R. J. Harvey, S. C. Chamberlain, S. S. Good, A. A. Smith III, M. G. Davis, C. L. Talarico, W. H. Miller, R. Ferris, R. E. Dornsife, S. C. Stanat, J. C. Drach, L. B. Townsend, and G. W. Koszalka. 2002. Potent and selective inhibition of human cytomegalovirus replication by 1263W94, a benzimidazole l-riboside with a unique mode of action. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:2365-2372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drew, W. L., R. C. Miner, G. I. Marousek, and S. Chou. 2006. Maribavir sensitivity of cytomegalovirus isolates resistant to ganciclovir, cidofovir or foscarnet. J. Clin. Virol. 37:124-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Evers, D. L., G. Komazin, R. G. Ptak, D. Shin, B. T. Emmer, L. B. Townsend, and J. C. Drach. 2004. Inhibition of human cytomegalovirus replication by benzimidazole nucleosides involves three distinct mechanisms. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:3918-3927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang, Y. C., J. L. Colaizzi, R. H. Bierman, R. Woestenborghs, and J. Heykants. 1986. Pharmacokinetics and dose proportionality of ketoconazole in normal volunteers. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 30:206-210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kern, E. R., C. B. Hartline, R. J. Rybak, J. C. Drach, L. B. Townsend, K. K. Biron, and D. J. Bidanset. 2004. Activities of benzimidazole d- and l-ribonucleosides in animal models of cytomegalovirus infections. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:1749-1755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koszalka, G. W., N. W. Johnson, S. S. Good, L. Boyd, S. C. Chamberlain, L. B. Townsend, J. C. Drach, and K. K. Biron. 2002. Preclinical and toxicology studies of 1263W94, a potent and selective inhibitor of human cytomegalovirus replication. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:2373-2380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krosky, P. M., M. C. Baek, and D. M. Coen. 2003. The human cytomegalovirus UL97 protein kinase, an antiviral drug target, is required at the stage of nuclear egress. J. Virol. 77:905-914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krosky, P. M., M. C. Baek, W. J. Jahng, I. Barrera, R. J. Harvey, K. K. Biron, D. M. Coen, and P. B. Sethna. 2003. The human cytomegalovirus UL44 protein is a substrate for the UL97 protein kinase. J. Virol. 77:7720-7727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lalezari, J. P., J. A. Aberg, L. H. Wang, M. B. Wire, R. Miner, W. Snowden, C. L. Talarico, S. Shaw, M. A. Jacobson, and W. L. Drew. 2002. Phase I dose escalation trial evaluating the pharmacokinetics, anti-human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) activity, and safety of 1263W94 in human immunodeficiency virus-infected men with asymptomatic HCMV shedding. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:2969-2976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lu, H., and S. Thomas. 2004. Maribavir (ViroPharma). Curr. Opin. Investig. Drugs 5:898-906. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ma, J. D., A. N. Nafziger, S. A. Villano, A. Gaedigk, and J. S. Bertino, Jr. 2006. Maribavir pharmacokinetics and the effects of multiple-dose maribavir on cytochrome P450 (CYP) 1A2, CYP 2C9, CYP 2C19, CYP 2D6, CYP 3A, N-acetyltransferase-2, and xanthine oxidase activities in healthy adults. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:1130-1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ogu, C. C., and J. L. Maxa. 2000. Drug interactions due to cytochrome P450. Baylor Univ. Med. Cent. Proc. 13:421-423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olkkola, K. T., J. T. Backman, and P. J. Neuvonen. 1994. Midazolam should be avoided in patients receiving the systemic antimycotics ketoconazole or itraconazole. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 55:481-485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Swan, S. K., W. B. Smith, T. C. Marbury, M. Schumacher, C. Dougherty, B. A. Mico, and S. A. Villano. 2007. Pharmacokinetics of maribavir, a novel oral anticytomegalovirus agent, in subjects with varying degrees of renal impairment. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 47:209-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang, L. H., R. W. Peck, Y. Yin, J. Allanson, R. Wiggs, and M. B. Wire. 2003. Phase I safety and pharmacokinetic trials of 1263W94, a novel oral anti-human cytomegalovirus agent, in healthy and human immunodeficiency virus-infected subjects. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:1334-1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Winston, D., J. van Burik, V. Pullarkat, G. Pananicolaou, R. Vij, E. Vance, G. Alangaden, R. Chemaly, F. Petersen, N. Chao, J. Klein, K. Sprague, C. Dougherty, S. Villano, and M. Boeckh. 2006. Prophylaxis against cytomegalovirus infections with oral maribavir in allogeneic stem cell transplant recipients: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Blood 108:Abstract 593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]