Abstract

Biofilms and planktonic cells of five Candida species were surveyed for the presence of persister (drug-tolerant) cell populations after exposure to amphotericin B. None of the planktonic cultures (exponential or stationary phase) contained persister cells. However, persisters were found in biofilms of one of two strains of Candida albicans tested and in biofilms of Candida krusei and Candida parapsilosis, but not in biofilms of Candida glabrata or Candida tropicalis. These results suggest that persister cells cannot solely account for drug resistance in Candida biofilms.

Most hospital-acquired implant infections attributable to fungi are caused by Candida albicans and other closely related Candida species (12). These organisms are able to form adherent biofilms on the surfaces of catheters, prosthetic heart valves, and other medical devices (7, 13, 22). Biofilm cells are organized into structured communities enclosed within a matrix of extracellular polymeric material. When grown in vitro on polyvinyl chloride (PVC) discs, biofilms of C. albicans consist of two layers: a thin basal region of densely packed yeast cells and an overlying thicker but more open hyphal layer (6). Biofilm cells are phenotypically distinct from planktonic or suspended cells. Most notably, they show significantly decreased susceptibility to antimicrobial agents (7, 13, 17, 22), and this makes implant infections very difficult to treat. Candida biofilms formed on PVC, polystyrene, polyurethane, and a variety of other surfaces are resistant to clinically important antifungal agents such as amphotericin B, fluconazole, and voriconazole.

The basis of biofilm drug resistance in Candida species is not yet clear. Possible mechanisms include (i) restricted drug penetration through the biofilm matrix, (ii) phenotypic changes resulting from a decreased growth rate or nutrient limitation, and (iii) expression of resistance genes induced by contact with a surface (7, 13, 17, 22). To date, most evidence suggests that drug resistance in Candida biofilms may be due to a combination of two or more of these mechanisms. Cell density (20), membrane sterols (18), and cell wall glucans (19) could also play a role. A further suggestion is that a small number of drug-tolerant or “persister” cells, like those known to be formed in bacterial biofilms, are responsible for resistance. Cells with the persister phenotype usually account for 0.1 to 1% of the biofilm population and can remain viable at high concentrations of antimicrobial agents (15, 16). The existence of such cells in C. albicans biofilms has been reported recently (10, 14). Persister cells can be detected in experiments designed to measure dose-dependent killing by an antimicrobial agent (14, 16). A biphasic killing curve, consisting of an initial drop in viable count followed by a level plateau of viable cells, indicates the presence of a subpopulation of microorganisms capable of surviving treatment with the drug. LaFleur et al. (14) reported killing curves of this type for C. albicans biofilms treated with two fungicidal agents, amphotericin B and chlorhexidine, up to a concentration of at least 100 μg ml−1. Here, we used a similar protocol with amphotericin B and both planktonic cells and biofilms of C. albicans and four other Candida species to investigate whether the persister phenotype is common among pathogenic fungi in the genus Candida.

Six Candida isolates were tested. C. albicans GDH 2346, Candida glabrata AAHB 12, Candida tropicalis AAHB 73, Candida parapsilosis AAHB 4479, and Candida krusei (Glasgow strain) are clinical isolates whose origins are described elsewhere (8). C. albicans SC5314 was kindly provided by N. A. R. Gow, University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen, Scotland. All organisms were maintained on slopes of Sabouraud dextrose agar (Difco). Stock solutions (8 mg ml−1) of amphotericin B (Sigma) were prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide and stored at −20°C.

Growth and amphotericin treatment of biofilms.

For biofilm studies, organisms were grown in yeast nitrogen base (YNB) medium (Difco) containing 50 mM glucose as described previously (8), and washed cell suspensions were adjusted to an optical density of 0.8 at 520 nm. Biofilms were formed on small discs (diameter, 0.8 cm) cut from PVC Faucher tubes (French gauge 36; Vygon, Cirencester, United Kingdom) essentially as reported elsewhere (5). The discs were placed in wells of 24-well Costar tissue culture plates, and a standardized cell suspension (80 μl) was applied to the surface of each one. Cells were allowed to adhere for 1 h at 37°C. Nonadherent organisms were removed by washing, and the discs were incubated in wells of a fresh plate for 48 h at 37°C, submerged in 1 ml of growth medium for biofilm formation. The biofilms were then treated with amphotericin B at concentrations ranging from 5 to 100 μg ml−1. Mature (48-h) biofilms were transferred to fresh wells, submerged in YNB glucose medium (1 ml) containing different concentrations of amphotericin and buffered to pH 7 with 0.165 M morpholinepropanesulfonic acid (MOPS; Sigma), and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. Control biofilms were incubated in buffered medium in the absence of amphotericin B. After incubation, biofilm cells were harvested from the discs by scraping and vigorous vortexing, washed twice in 0.15 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.2, and resuspended in more PBS (100 μl). Viable counts were then determined by the standard procedure of serial dilution followed by plating on YNB agar containing 200 mM glucose.

Growth and amphotericin treatment of planktonic cells.

All organisms were grown at 37°C with shaking in YNB medium containing 50 mM glucose (50 ml in 250-ml flasks). Exponential-phase cultures were incubated for 8 h (C. krusei, C. albicans, and C. tropicalis), 11 h (C. parapsilosis), or 18 h (C. glabrata). Stationary-phase cultures of all species were incubated for 48 h. Cells from samples (100 μl) of exponential- or stationary-phase cultures were harvested and washed twice in PBS. Washed cells were treated in microtiter plates with different concentrations of amphotericin B (5 to 100 μg ml−1) in YNB glucose medium buffered to pH 7 with 0.165 M MOPS. Control cells were treated similarly with buffered medium without amphotericin B. Since cell density affects antifungal drug resistance (20), all cell suspensions were adjusted to a concentration (approximately 107 cells ml−1) equivalent to that of resuspended biofilms. After incubation at 37°C for 24 h, the cells were washed twice and resuspended in PBS (100 μl). Viable counts were then carried out by serial dilution and plating on YNB agar containing 200 mM glucose.

Presence of persisters in C. albicans biofilms and planktonic cultures.

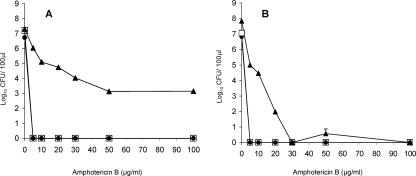

Exposure to amphotericin B at a concentration of 5 μg ml−1 effectively killed both exponential- and stationary-phase planktonic cells of strain GDH 2346, with no detectable survivors. The MIC for this strain is 1.3 μg ml−1 (9). Biofilms, on the other hand, appeared to contain a small proportion (0.01%) of cells resistant to an amphotericin B concentration of at least 100 μg ml−1 (Fig. 1A). These results are similar to those of LaFleur et al. (14), who recently demonstrated the existence of persisters in several C. albicans strains, although in rather higher numbers (0.05 to 2% of the total population) than those detected here. Our results also confirm the additional observation by the same group that persisters are absent in planktonic cultures of C. albicans. This finding is strikingly different from earlier results with bacteria which showed that stationary-phase planktonic populations contain more persisters than do biofilms (23). In contrast, biofilms of C. albicans SC5314, like both exponential- and stationary-phase planktonic cells of this strain, appeared to lack persisters completely in that no cells survived an amphotericin B concentration of 100 μg ml−1 (Fig. 1B). However, biofilm cells were more resistant to the drug than either type of planktonic cell. These results indicate that persister populations are not universally present in C. albicans biofilms.

FIG. 1.

Survival of biofilm cells (▴), planktonic exponential-phase cells (•), and planktonic stationary-phase cells (□) of C. albicans GDH 2346 (A) and C. albicans SC5314 (B) exposed to different concentrations of amphotericin B. Results are means ± standard errors of two independent experiments carried out in duplicate.

Presence of persisters in biofilms and planktonic cultures of other Candida species.

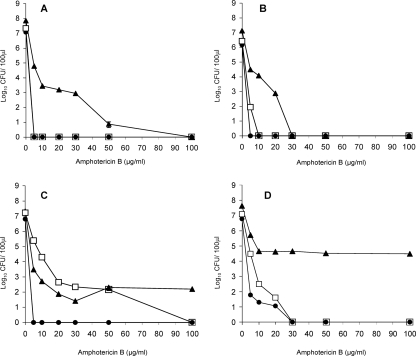

As expected, planktonic cells of the non-C. albicans species tested, like those of C. albicans, were more susceptible to amphotericin B than were biofilms (Fig. 2). Exponential-phase planktonic cells of C. glabrata, C. tropicalis, and C. krusei were killed by a drug concentration of 5 μg ml−1 (Fig. 2A, B, and C), although those of C. parapsilosis were rather more resistant (Fig. 2D). Stationary-phase planktonic cells of C. tropicalis, C. krusei, and C. parapsilosis were less susceptible than exponential-phase cells (Fig. 2B, C, and D), with those of C. krusei showing a marked resistance to the drug (Fig. 2C). However, in no case was there any evidence of persisters, since all of these cultures were completely killed at an amphotericin B concentration of 100 μg ml−1. These findings are similar to those obtained for planktonic cells of C. albicans, both in this study and in the earlier investigation of LaFleur et al. (14). Although biofilms of all four non-C. albicans species were considerably more resistant to amphotericin B than planktonic cells, only biofilms of C. krusei and C. parapsilosis gave biphasic killing curves indicative of the presence of persisters (Fig. 2C and D). These biofilms, unlike those of C. glabrata and C. tropicalis, still showed some viability even after exposure to a drug concentration of 100 μg ml−1. However, for both species the persister population was small, representing approximately 0.001% and 0.07% of the total cell count of biofilms of C. krusei and C. parapsilosis, respectively.

FIG. 2.

Survival of biofilm cells (▴), planktonic exponential-phase cells (•), and planktonic stationary-phase cells (□) of C. glabrata AAHB 12 (A), C. tropicalis AAHB 73 (B), C. krusei (Glasgow strain) (C), and C. parapsilosis AAHB 4479 (D) exposed to different concentrations of amphotericin B. Results are means ± standard errors of two independent experiments carried out in duplicate.

Persisters were originally described as dormant or nongrowing cells (16) but are now recognized as drug-tolerant cells that neither grow nor die in the presence of microbicidal antibiotics. The ability to avoid killing is their key characteristic (11). In bacteria, persisters were first identified in planktonic cultures as phenotypic variants, not mutants; subsequently, the high tolerance of bacterial biofilms to antimicrobial agents was attributed largely to the presence of persisters by some investigators (15, 16). In contrast, planktonic cultures of all of the Candida species tested here appeared to lack persisters. Similarly, using the criteria adopted previously for C. albicans (14), persisters were absent from biofilms of some species. Where persisters were found, they were present in low numbers (0.001 to 0.07%). It is unlikely that these cells were mutants since acquired resistance to amphotericin B is rare. Moreover, LaFleur et al. in their earlier study (14) clearly demonstrated that C. albicans persisters were phenotypic variants, not mutants, of the wild type.

A recent investigation by Khot et al. (11) also identified a small subpopulation of cells in C. albicans biofilms showing increased tolerance to amphotericin B. The biofilms were cultured in a tubular flow cell and exhibited typical C. albicans biofilm architecture (6, 7), consisting of a thin basal yeast layer and an overlying thicker, partly filamentous layer. After growth, most of the biofilm was removed by draining and washing the tubing, but a monolayer of yeast cells remained on the surface. In dose-response experiments with amphotericin B, this yeast subpopulation showed greater tolerance of the drug than biofilm cells removed by washing (10). Metabolic activity, rather than viability, was measured after exposure to a range of amphotericin B concentrations for 1 h. The dose-response curve for the basal yeast cells decreased to a plateau of approximately 50% metabolic activity between a drug concentration of 3.7 μg ml−1 and the highest concentration of 28 μg ml−1. Whether these cells represent a population of persisters, as defined here, is not clear. Conversely, we have no way of knowing whether the persister population identified in biofilms of C. albicans GDH 2346 in this study consisted entirely of yeast cells.

The mechanisms by which Candida biofilms resist the action of antifungal agents are poorly understood. The biofilm matrix does not appear to form a major barrier to drug penetration since antifungal agents permeate Candida biofilms relatively easily (1). However, under flow conditions resembling those found in catheter infections in vivo, increased production of matrix polymers can contribute to drug resistance (2). Studies with a perfused biofilm fermentor (3) have shown that drug resistance is not simply due to a low growth rate, and a related investigation (4) demonstrated that iron limitation of biofilm growth is not solely responsible. It is possible that expression of resistance genes is induced by contact with a surface. For example, genes encoding multidrug efflux pumps in C. albicans are upregulated during biofilm formation and development. However, mutants lacking these genes are drug sensitive when growing planktonically but still drug resistant during biofilm growth (21). The recent attractive suggestion that a small number of persister cells are responsible for resistance (14) is not wholly supported by the present study. Although persister populations are present in biofilms of several C. albicans isolates (14), our results demonstrate that persisters are absent from those of at least one well-characterized strain, C. albicans SC5314. Similarly, while biofilms of C. krusei and C. parapsilosis appear to harbor persister cells, biofilms of C. glabrata and C. tropicalis are devoid of such cells. Biofilm drug resistance in Candida species therefore remains unexplained and is most likely multifactorial in nature.

Acknowledgments

Rawya Al-Dhaheri is the recipient of a research studentship from the Health Authority, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 19 February 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Al-Fattani, M. A., and L. J. Douglas. 2004. Penetration of Candida biofilms by antifungal agents. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:3291-3297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Fattani, M. A., and L. J. Douglas. 2006. Biofilm matrix of Candida albicans and Candida tropicalis: chemical composition and role in drug resistance. J. Med. Microbiol. 55:999-1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baillie, G. S., and L. J. Douglas. 1998. Effect of growth rate on resistance of Candida albicans biofilms to antifungal agents. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:1900-1905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baillie, G. S., and L. J. Douglas. 1998. Iron-limited biofilms of Candida albicans and their susceptibility to amphotericin B. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:2146-2149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baillie, G. S., and L. J. Douglas. 1999. Candida biofilms and their susceptibility to antifungal agents. Methods Enzymol. 310:644-656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baillie, G. S., and L. J. Douglas. 1999. Role of dimorphism in the development of Candida albicans biofilms. J. Med. Microbiol. 48:671-679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Douglas, L. J. 2003. Candida biofilms and their role in infection. Trends Microbiol. 11:30-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hawser, S. P., and L. J. Douglas. 1994. Biofilm formation by Candida species on the surface of catheter materials in vitro. Infect. Immun. 62:915-921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hawser, S. P., and L. J. Douglas. 1995. Resistance of Candida albicans biofilms to antifungal agents in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:2128-2131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keren, I., N. Kaldalu, A. Spoering, Y. Wang, and K. Lewis. 2004. Persister cells and tolerance to antimicrobials. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 230:13-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khot, P. D., P. A. Suci, R. L. Miller, R. D. Nelson, and B. J. Tyler. 2006. A small subpopulation of blastospores in Candida albicans biofilms exhibit resistance to amphotericin B associated with differential regulation of ergosterol and β-1,6-glucan pathway genes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:3708-3716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kojic, E. M., and R. O. Darouiche. 2004. Candida infections of medical devices. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 17:255-267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumamoto, C. A. 2002. Candida biofilms. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 5:608-611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.LaFleur, M. D., C. A. Kumamoto, and K. Lewis. 2006. Candida albicans biofilms produce antifungal-tolerant persister cells. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:3839-3846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lewis, K. 2001. Riddle of biofilm resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:999-1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lewis, K. 2007. Persister cells, dormancy and infectious disease. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5:48-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mukherjee, P. K., and J. Chandra. 2004. Candida biofilm resistance. Drug Resist. Updat. 7:301-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mukherjee, P. K., J. Chandra, D. M. Kuhn, and M. A. Ghannoum. 2003. Mechanism of fluconazole resistance in Candida albicans biofilms: phase-specific role of efflux pumps and membrane sterols. Infect. Immun. 71:4333-4340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nett, J., L. Lincoln, K. Marchillo, R. Massey, K. Holoyda, B. Hoff, M. VanHandel, and D. Andes. 2007. Putative role of β-1,3 glucans in Candida albicans biofilm resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:510-520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perumal, P., S. Mekala, and W. L. Chaffin. 2007. Role for cell density in antifungal drug resistance in Candida albicans biofilms. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:2454-2463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ramage, G., S. Bachmann, T. F. Patterson, B. L. Wickes, and J. L. Lopez-Ribot. 2002. Investigation of multidrug efflux pumps in relation to fluconazole resistance in Candida albicans biofilms. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 49:973-980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ramage, G., S. P. Saville, D. P. Thomas, and J. L. López-Ribot. 2005. Candida biofilms: an update. Eukaryot. Cell 4:633-638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spoering, A. L., and K. Lewis. 2001. Biofilms and planktonic cells of Pseudomonas aeruginosa have similar resistance to killing by antimicrobials. J. Bacteriol. 183:6746-6751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]