Abstract

Nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae (NTHi) causes pulmonary infections in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and other mucociliary clearance defects. Like many bacteria inhabiting mucosal surfaces, NTHi produces lipooligosaccharide (LOS) endotoxins that lack the O side chain. Persistent NTHi populations express a discrete subset of LOS glycoforms, including those containing phosphorylcholine (PCho). In this study, we compared two NTHi strains with isogenic mutants lacking PCho for clearance from mice following pulmonary infection. Consistent with data from other model systems, populations of the strains NTHi 2019 and NTHi 86-028NP recovered from mouse lung contained an increased proportion of PCho+ variants compared to that in the inocula. PCho− mutants were more rapidly cleared. Serial passage of NTHi increased both PCho content and bacterial resistance to clearance, and no such increases were observed for PCho− mutants. Increased PCho content was also observed in NTHi populations within non-endotoxin-responsive C3H/HeJ and Toll-like receptor 4 null (TLR4−/−) mice, albeit at later times postinfection. Changes in bacterial subpopulations and clearance were unaffected in TLR2−/− mice compared to the subpopulations in and clearance from mice of the parental strain. The clearance of PCho− mutants occurred at earlier time points in both strain backgrounds and in all types of mice. Comparison of bacterial populations in lung tissue cryosections by immunofluorescent staining showed sparse bacteria within the air spaces of C57BL/6 mice and large bacterial aggregates within the lungs of MyD88−/− mice. These results indicate that PCho promotes bacterial resistance to pulmonary clearance early in infection in a manner that is at least partially independent of the TLR4 pathway.

Nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae (NTHi) is a human-specific commensal of the nasopharynx and upper airways. In contrast to encapsulated H. influenzae strains that cause invasive disease, NTHi strains are genetically diverse and aclonal (34). During normal carriage, NTHi causes no overt pathology and may in fact provide an immune stimulus that promotes the containment of other organisms (25). When mucociliary clearance is impaired, NTHi can cause opportunistic infections that include sinusitis, bronchitis, and otitis media (11). NTHi is also a major cause of infections associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (9, 14, 31), which is one of the most prevalent diseases affecting adults worldwide (28). Patients with COPD are colonized in their upper and lower airways with NTHi and other bacteria, which may persist for months or even years; changes in the subpopulations of bacteria within the COPD patient lung can be a determinant of the progression and severity of disease (41, 42, 44).

Clearance of NTHi bacteria from the lung is mediated by both innate and adaptive immune defenses. NTHi elicits a robust antibody response directed against a number of different surface moieties, and a substantial number of studies indicate that at least a subset of these antibodies may confer protection and/or bacterial clearance (1, 4, 8, 19, 21, 29, 33, 35, 36, 38, 66). Additional data indicate that cell-mediated immunity may also be important in the clearance or containment of NTHi infection in COPD patients (20).

As is true for many opportunistic organisms, the innate host response directed against H. influenzae bacteria and their components initiates bacterial clearance from the airway (58). Like most gram-negative bacteria, H. influenzae produces endotoxin that is predominantly hexa-acylated (23) and evokes host cell responses via Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) (22, 37). H. influenzae bacteria also produce proteins and lipoproteins that are recognized by TLR2 (6, 12, 45, 46, 57). Recent work indicates that intact H. influenzae bacteria also activate the TLR9 pathway, in addition to the TLR2 and TLR4 pathways (30). The central role of TLR4 activation in the pulmonary clearance of H. influenzae has been well established (58) and is dependent on the MyD88-dependent host cell signal pathway (65).

H. influenzae endotoxins are lipooligosaccharides (LOS) that lack the repeating O side chains typical of enteric bacteria (39). Instead, H. influenzae produces a highly diverse assortment of LOS glycoforms. The composition and structure of the H. influenzae LOS constantly shift due to temporal regulation and phase variation of genes involved in its assembly (40, 49, 59). LOS oligosaccharides contain epitopes that are also found on host cells, and thus NTHi is thought to persist via host mimicry that may blunt immune clearance (32). One of the host structures found in the H. influenzae LOS is phosphorylcholine (PCho), which is scavenged from host cells via the GlpQ phospholipase (10) and added to a discrete subset of LOS acceptors (26, 62). Prior work has shown that PCho confers a number of persistence-related phenotypes on NTHi bacteria, including host cell adherence and invasion (47, 50) and resistance to some host-derived antimicrobials (27). Recent work from our laboratory also shows that persistence in biofilm communities results in an increased PCho content of NTHi endotoxin and diminished host cell responses, presumably by affecting the TLR4 pathway (16, 64). In this study, we compare the levels of clearance of isogenic NTHi strains with and without PCho from the mouse lung following pulmonary infection. The results indicate that variants expressing PCho are better able to resist clearance from the mouse lung than mutants lacking PCho. Serial passage increased both PCho content and the length of bacterial persistence, and both phenotypes were lacking in PCho− mutants. Similar effects of PCho on persistence were observed in C3H/HeJ non-endotoxin-responsive mice. Thus, we conclude that PCho blunts the pulmonary clearance of NTHi by innate host defenses, albeit in a manner that may not be strictly TLR4 dependent.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria.

The NTHi strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. All NTHi strains were cultured at 37°C on brain heart infusion (BHI) agar (Difco) supplemented with 10 μg/ml hemin chloride (ICN) and 10 μg/ml β-nicotinamide adenine dinncleotide (Sigma). Hereinafter, this medium is referred to as supplemented BHI (sBHI) agar.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and phenotypes

To prepare the inocula, bacteria were grown on sBHI agar plates overnight, suspended in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and diluted to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.150 (1 × 108 CFU/ml). The inoculum concentration was confirmed by standard colony plate counting.

Mice.

C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA) or from the mouse repository at the National Cancer Institute (Bethesda, MD). C3H/HeN mice were purchased from the NCI. C3H/HeJ mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Breeding pairs of MyD88−/− (2), TLR2−/− (52), and TLR4−/− (17) mice were generously provided by Shizuo Akira via Elizabeth Hiltbold (Department of Microbiology and Immunology, WFUHS). All mice were 8 to 10 weeks of age and were housed under pathogen-free conditions.

Mouse lung infection.

The mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection with 2,2,2-tribromoethanol (Avertin) and infected intratracheally with ∼3 × 106 CFU of bacteria. At various times postinfection, the mice were anesthetized with 2,2,2-tribromoethanol and then euthanized by cervical dislocation. After the lungs were exposed, the pulmonary vascular system was flushed via the right ventricle with sterile PBS. The left lung of each mouse was homogenized, serially diluted, and spread onto sBHI agar plates, which were incubated overnight for plate counts. For each mouse, the right lung was infused with 4% paraformaldehyde for histopathologic analyses.

Paraffin sections and histopathology analysis.

Fixed tissue specimens were dehydrated and embedded in paraffin. Sections (5 μm) were cut from paraffin-embedded blocks on a microtome and mounted from warm water (40°C) onto adhesive microscope slides. After serial deparaffinization and rehydration, tissue sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin for histopathology assessment.

Cryosectioning and immunofluorescence staining.

Fixed tissue samples were rinsed with 1× PBS at room temperature and placed into Cryomold (Sakura Finetek USA, Torrance, CA). Octyldecyl silane compound (Sakura Finetek USA, Torrance, CA) was added, and the blocks were frozen at −70°C for 1 h. Serial 5-μm sections were cut with an Accu-Edge low-profile blade (Feather Safety Razor, Japan) at −20°C and stored at −70°C. Immunofluorescence staining was performed using rabbit antisera recognizing NTHi and anti-PCho antibody, essentially as described previously (47).

LOS analysis.

From lung homogenate bacterial isolates, LOS was isolated using a modified proteinase K procedure (3, 18). Briefly, bacteria were harvested from sBHI agar plates from the lung homogenates after 24 h of incubation, diluted to an optical density at 650 nm of 0.90 (1 × 109 CFU/ml) in sterile PBS, pelleted, and then lysed in 2.0% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 10 mM EDTA, 0.06 M Tris (pH 6.8). After overnight treatment with 2.5 μg/ml proteinase K (Sigma), the lysates were boiled for 5 min and digested overnight with 10 units staphylococcal nuclease (Sigma). LOS was precipitated with sodium acetate-ethanol, dialyzed overnight, and lyophilized. LOS was analyzed by Tricine-SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) (24) and visualized by ammonia silver staining (56). PCho was measured by immunoblotting with anti-PCho monoclonal antibody TEPC-15 (Sigma) or HAS (Statens Serum Institut).

Data analysis.

Statistical analyses of the bacterial counts were performed using the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test. As per standard practice, data sets for which P values of ≤0.05 were obtained were deemed significantly different.

RESULTS

NTHi mutants lacking PCho are readily cleared from mouse lungs.

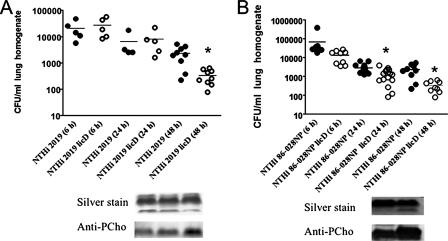

It has long been appreciated that H. influenzae populations in vivo are enriched for PCho+ variants (16, 55, 60, 61). We used a mouse pulmonary-infection model to determine whether PCho affects the pulmonary persistence and/or the clearance of NTHi. The levels of clearance of two well-characterized NTHi strains (NTHi 2019 and NTHi 86-028NP) after intratracheal infection were compared with those of isogenic licD mutants lacking PCho (Fig. 1). The results show that significantly fewer licD bacteria than bacteria of the parental NTHi 2019 strain were recovered 48 h postinfection (Fig. 1A). Similarly, significantly fewer NTHi 86-028NP licD bacteria than bacteria of the parental strain were recovered from lung homogenates at 24 and 48 h postinfection. Notably, there were significant differences in the kinetics of clearance of the two strains following infection, which is similar to the well-documented differences in the levels of persistence/clearance of individual NTHi strains in patient carriage studies (41, 43) and in our recently published work with the chinchilla model of otitis media (15). The results also show a significant increase in the clearance of PCho− licD mutants of both strains. Thus, we conclude that PCho delays the clearance of NTHi in pulmonary infections. As NTHi populations contain various percentages of PCho+ and PCho− variants, we next asked whether lung carriage resulted in an increased number of PCho+ variants compared to the number in the inocula. LOS was purified from inocula and mouse-passaged bacteria and analyzed for PCho content by Tricine-SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting. The data show that the amount of LOS PCho increases in recovered NTHi 2019 and NTHi 86-028NP bacteria at 24 and 48 h postinfection (Fig. 1, insets). These results are consistent with the hypothesis advanced by several groups that selective pressure within the lung may favor NTHi variants with PCho+ LOS forms (15, 55, 60, 61).

FIG. 1.

PCho− mutants of NTHi are readily cleared from mouse lungs. Symbols represent numbers of CFU recovered from individual mouse lungs after infection with NTHi 2019 or NTHi 2019 licD (A) and NTHi 86-028NP or NTHi 86-028NP licD (B). Statistical means are shown as horizontal bars. An asterisk indicates a significant difference from the value for the wild-type strain. LOS was purified from NTHi 2019 or NTHi 86-028NP bacteria in the inoculum; bacteria were recovered from C57BL/6 mouse lungs at 24 h and 48 h postinfection and analyzed by Tricine-SDS-PAGE, followed by silver staining and immunoblotting as described in Materials and Methods.

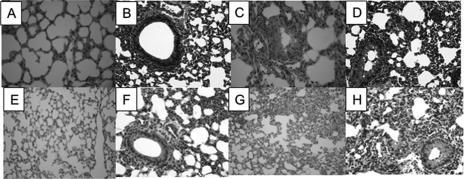

Histopathologic analysis of lung tissue from infected mice.

Lungs from infected mice were sectioned and stained for histopathology assessment (Fig. 2). The sections were examined blind as sets by a trained veterinary pathologist (N. Kock). Airway epithelia were examined for signs of membrane damage, apoptotic cells, and vesicle formation. Edema was scored based on the size of the affected area, and cellular infiltration was assessed. For each lung, an overall semiquantitative inflammatory score was assessed by compiling all of the criteria. The results showed a greater overall inflammation score for animals infected with the licD mutant strains at the earliest time point (6 h) postinfection than those for animals infected with parental strains (Fig. 2). No other significant differences were noted. Immunofluorescent staining of lung cryosections showed diffuse distribution of individual bacteria within the lung at the earliest time points, with little staining observed thereafter (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Histopathologic analysis of infected mouse lung tissue. Sections were stained and scored in a blind fashion for inflammatory markers as described in Materials and Methods. (A to D) Light micrographs of hematoxylin- and eosin-stained paraffin sections from mice infected with NTHi 2019 (A and B), NTHi 2019 licD (C and D), NTHi 86-028NP (E and F), or NTHi 86-028NP licD (G and H).

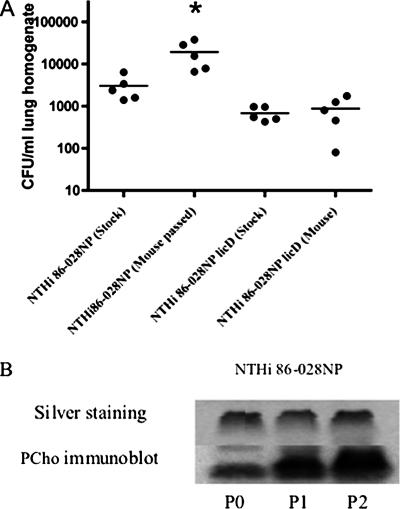

Repeated passage increases the resistance of NTHi 86-028NP to clearance from mouse lungs.

Because the passage of NTHi in mouse lungs enriches for PCho+ variants, we reasoned that if PCho promotes resistance to clearance, then the length of NTHi persistence in the mouse lung would increase with serial passage in accordance with PCho content. NTHi 86-028NP bacteria (mouse passaged) recovered from the first round of mouse lung infection as well as NTHi 86-028NP bacteria (original stock) that had not been passaged through a mouse lung were used as inocula for another round of mouse lung infection. The mice infected with similarly passaged NTHi 86-028NP licD served as controls. The data show that there were significantly more NTHi 86-028NP bacteria recovered from the repeated passage than from the original stock. However, no such increase in bacterial numbers was observed with the mouse-passaged NTHi 86-028NP licD bacteria (Fig. 3). Analysis of LOS purified from these bacteria showed an increase in PCho content coinciding with increased passage (Fig. 3B). We thus conclude that carriage results in NTHi populations that are more resistant to host clearance, in accordance with increased PCho content.

FIG. 3.

Repeated passage increases the resistance of NTHi to clearance from mouse lung. (A) Comparison of CFU counts from mice infected with NTHi 86-028NP before and after mouse passage. Horizontal bars represent the statistical means. The asterisk denotes statistically significant differences. (B) Comparison of PCho contents in LOS from mouse-passaged strains and stock strains. LOS was purified and analyzed as described for the preceding figures.

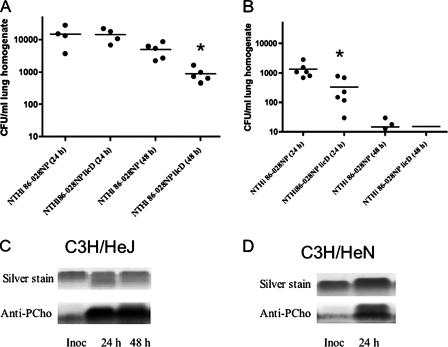

PCho increases the resistance of NTHi to clearance from mouse lung mediated by TLR4 in vivo.

The host response to Haemophilus influenzae in the lung is largely mediated by TLR4 (58, 65), and our recent work shows that the growth of NTHi in biofilms results in diminished LOS bioactivity in conjunction with increased PCho content (64). Thus, we asked whether the increased resistance to clearance associated with PCho is directly related to TLR4. NTHi clearance was compared in endotoxin-responsive (C3H/HeN) and endotoxin-nonresponsive (C3H/HeJ) mice. In accordance with prior work, higher counts of NTHi bacteria were observed in the lungs of C3H/HeJ mice (Fig. 4A) than in the lungs of C3H/HeN mice (Fig. 4B). In the C3H/HeN mice, we observed significant differences in the levels of clearance of the parental NTHi strain and the licD mutant (Fig. 4B), which were consistent with the infection studies performed using C57BL/6 mice (Fig. 1). However, the only significant differences in CFU counts from C3H/HeJ mice were observed at later time points (Fig. 4A). Analysis of LOS purified from the NTHi bacteria revealed that the proportion of PCho+ bacteria increased even in the absence of the TLR4 response, albeit at later time points (Fig. 4C and D). Comparable results were obtained using TLR4−/− mice (data not shown). In parallel experiments, we saw no difference in either CFU counts or the magnitude or timing of the shift in PCho+ subpopulations between TLR2−/− mice and mice of the parental strain (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Role of TLR4 in PCho-related NTHi clearance resistance. Graphs depict numbers of bacterial CFU recovered from the infected lungs of C3H/HeJ (A) or C3H/HeN (B) mice. Asterisks denote statistically significant differences. The PCho contents of purified LOS are shown for bacteria recovered from C3H/HeN mice (C) or C3H/HeJ mice (D) at 24 and 48 h postinfection. Inoc, inoculum.

NTHi persistence in MyD88−/− mouse lungs.

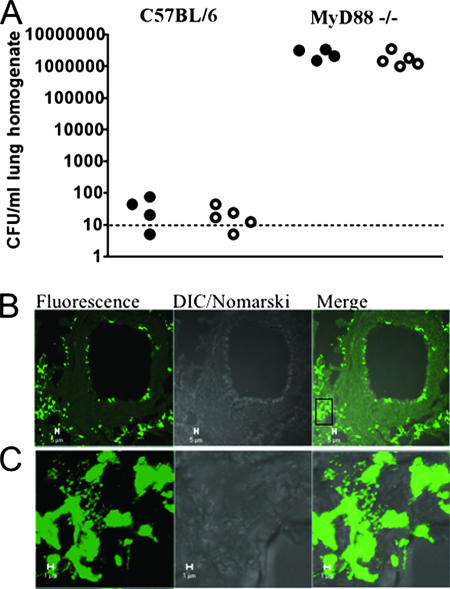

The data indicated that the increase in PCho+ variants was temporally related to the inflammatory response. Prior studies showed that H. influenzae clearance was severely impaired in MyD88−/− mice (65). Therefore, if our hypothesis that the inflammatory response promotes the observed increase in PCho+ subpopulations, then a PCho− mutant should have no defect in this mouse background. Comparison of levels of clearance of NTHi 2019 and NTHi 2019 licD from C57BL/6 mice and isogenic MyD88−/− mice revealed that the difference in clearance associated with the loss of PCho was absent in the absence of MyD88 (Fig. 5A). Likewise, there was no difference in the markers of inflammation in sections of lung tissue from MyD88−/− mice infected with NTHi 2019 and NTHi 2019 licD (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

NTHi persistence in MyD88−/− mice. C57BL/6 mice and isogenic MyD88−/− mice were infected intratracheally with NTHi 2019 (filled circles) or NTHi 2019 licD (open circles). At 72 h postinfection, mice were euthanized and their lungs were excised. (A) CFU counts from lung homogenates from infected mice. (B) Representative images obtained following immunofluorescent staining of NTHi bacteria (green) within cryosections of lung tissue of MyD88−/− mice. Multicellular communities were readily visible throughout the lung. DIC, differential inference contrast optics. (C) Higher-magnification image of the area in the boxed region in panel B. Bars in panels B and C indicate 5 and 1 μm, respectively.

We next analyzed cryosections of infected lung tissue from MyD88−/− mice by immunofluorescent microscopy (Fig. 5B and C). At 72 h postinfection, we observed multicellular bacterial communities within the lung tissue. No such communities were observed in infected lungs from C57BL/6 mice.

DISCUSSION

As a commensal, NTHi is highly adapted to resist host clearance and persist in the airways. Our prior work showed that LOS modifications occurring in vivo, such as sialylation and the addition of PCho, impact a variety of persistence-associated bacterial phenotypes that include adherence to and invasion of airway cells and dampening of the inflammatory response (47, 48, 50, 51, 64). In this study, we sought to address how PCho content affects bacterial persistence in the lung. Mouse pulmonary infections are a well-established model system for airway persistence/clearance for many organisms, including NTHi (53, 54). Thus, we compared the levels of clearance of two different NTHi strains and their isogenic licD mutants from the mouse lung. The data show that carriage in vivo enriches for PCho+ variants (Fig. 1), as has been well established in patient studies and with animal models (16, 55, 60, 61). Moreover, our data show that serial passage confers an enhanced persistence phenotype on NTHi and that this is lacking in PCho− mutants (Fig. 3). These results are consistent with our recently published work showing that PCho− mutants of NTHi have a defect in biofilm formation within the chinchilla middle ear (15, 16).

Additional information gleaned from the infection studies using mutant mice includes the finding that the shift to PCho+ variants and the enhanced persistence of PCho+ variants compared to PCho− mutants were delayed in non-endotoxin-responsive mice (Fig. 4). These findings link the fitness advantage of PCho+ variants to host responses to LOS early in infection, which is consistent with our recent observation that PCho blunts host inflammatory responses to NTHi LOS and bacteria (15, 64). The contribution of PCho to the colonization and persistence of H. influenzae is multifactorial. In addition to having anti-inflammatory effects, PCho adheres to host cells, which is mediated by its binding to the platelet-activating factor receptor (13, 47, 50), it enhances resistance to some host antimicrobials (27), and it promotes biofilm formation both in vitro and in vivo (16).

Our infection studies using TLR2−/− mice do not support a significant role for this pathway in NTHi persistence or in the shift in variants expressing PCho. These data are consistent with findings from other groups (65) and support the conclusion that the TLR4 response is important in the early innate response to NTHi infection. These data are also consistent with prior work showing that TLR4 and TLR2 responses had different temporal roles in innate defenses against Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium infection in mice (63).

In summary, this study clarifies the role of a surface modification common to many mucosa-adapted pathogens in bacterial persistence in vivo. Ongoing work in our laboratory is devoted to more fully defining the adaptive strategies used by NTHi to persist in the airways. As NTHi causes opportunistic infections that are a major public health problem, defining how the organism persists in vivo is an essential step in learning to better prevent and/or manage these infections.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the outstanding technical contributions of Gayle Foster and Vadim Ciobanu and helpful discussions and feedback provided by colleagues in the WFUHS Bacterial Pathogenesis Group.

This work was supported by NIH research grant AI054425. Dana Winn and Ryan Johnson were supported by an NIH-sponsored summer training program (grant T35DK007400 to Richard St. Clair, principal investigator), and Shayla West-Barnette was supported by an NIH individual predoctoral fellowship (grant AI061830).

Editor: J. N. Weiser

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 17 March 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abe, Y., T. F. Murphy, S. Sethi, H. S. Faden, J. Dmochowski, Y. Harabuchi, and Y. M. Thanavala. 2002. Lymphocyte proliferative response to P6 of Haemophilus influenzae is associated with relative protection from exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 165967-971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adachi, O., T. Kawai, K. Takeda, M. Matsumoto, H. Tsutsui, M. Sakagami, K. Nakanishi, and S. Akira. 1998. Targeted disruption of the MyD88 gene results in loss of IL-1- and IL-18-mediated function. Immunity 9143-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Apicella, M. A., J. M. Griffiss, and H. Schneider. 1994. Isolation and characterization of lipopolysaccharides, lipooligosaccharides and lipid A. Methods Enzymol. 235242-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bakaletz, L. O., B. J. Kennedy, L. A. Novotny, G. Duquesne, J. Cohen, and Y. Lobet. 1999. Protection against development of otitis media induced by nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae by both active and passive immunization in a chinchilla model of virus-bacterium superinfection. Infect. Immun. 672746-2762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bakaletz, L. O., B. M. Tallan, T. Hoepf, T. F. DeMaria, H. G. Birck, and D. J. Lim. 1988. Frequency of fimbriation of nontypable Haemophilus influenzae and its ability to adhere to chinchilla and human respiratory epithelium. Infect. Immun. 56331-335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berenson, C. S., T. F. Murphy, C. T. Wrona, and S. Sethi. 2005. Outer membrane protein P6 of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae is a potent and selective inducer of human macrophage proinflammatory cytokines. Infect. Immun. 732728-2735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campagnari, A. A., M. R. Gupta, K. C. Dudas, T. F. Murphy, and M. A. Apicella. 1987. Antigenic diversity of lipooligosaccharides of nontypable Haemophilus influenzae. Infect. Immun. 55882-887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cutter, D., K. W. Mason, A. P. Howell, D. L. Fink, B. A. Green, and I. J. St. Geme. 2002. Immunization with Haemophilus influenzae Hap adhesin protects against nasopharyngeal colonization in experimental mice. J. Infect. Dis. 1861115-1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eldika, N., and S. Sethi. 2006. Role of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae in exacerbations and progression of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 12118-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fan, X., H. Goldfine, E. Lysenko, and J. N. Weiser. 2001. The transfer of choline from the host to the bacterial cell surface requires glpQ in Haemophilus influenzae. Mol. Microbiol. 411029-1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Foxwell, A. R., J. M. Kyd, and A. W. Cripps. 1998. Nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae: pathogenesis and prevention. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62294-308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galdiero, M., M. Galdiero, E. Finamore, F. Rossano, M. Gambuzza, M. R. Catania, G. Teti, A. Midiri, and G. Mancuso. 2004. Haemophilus influenzae porin induces Toll-like receptor 2-mediated cytokine production in human monocytes and mouse macrophages. Infect. Immun. 721204-1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gould, J. M., and J. N. Weiser. 2002. The inhibitory effect of C-reactive protein on bacterial phosphorylcholine platelet-activating factor receptor-mediated adherence is blocked by surfactant. J. Infect. Dis. 186361-371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Groeneveld, K., P. P. Eijk, L. van Alphen, H. M. Jansen, and H. C. Zanen. 1990. Haemophilus influenzae infections in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease despite specific antibodies in serum and sputum. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1411316-1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hong, W., K. Mason, J. A. Jurcisek, L. A. Novotny, L. O. Bakaletz, and W. E. Swords. 2007. Phosphorylcholine decreases early inflammation and promotes the establishment of stable biofilm communities of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae strain 86-028NP in a chinchilla model of otitis media. Infect. Immun. 75958-965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hong, W., B. Pang, S. West-Barnette, and W. E. Swords. 2007. Phosphorylcholine expression by nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae correlates with maturation of biofilm communities in vitro and in vivo. J. Bacteriol. 1898300-8307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoshino, K., O. Takeuchi, T. Kawai, H. Sanjo, T. Ogawa, Y. Takeda, K. Takeda, and S. Akira. 1999. Cutting edge: Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)-deficient mice are hyporesponsive to lipopolysaccharide: evidence for TLR4 as the Lps gene product. J. Immunol. 1623749-3752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones, P. A., N. A. Samuels, N. J. Phillips, R. S. Munson, J. A. Bozue, J. A. Arseneau, W. A. Nichols, A. Zaleski, B. W. Gibson, and M. A. Apicella. 2002. Haemophilus influenzae type B strain A2 has multiple sialyltransferases involved in lipooligosaccharide sialylation. J. Biol. Chem. 27714598-14611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kennedy, B. J., L. A. Novotny, J. A. Jurcisek, Y. Lobet, and L. O. Bakaletz. 2000. Passive transfer of antiserum specific for immunogens derived from a nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae adhesin and lipoprotein D prevents otitis media after heterologous challenge. Infect. Immun. 682756-2765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.King, P. T., P. E. Hutchinson, P. D. Johnson, P. W. Holmes, N. J. Freezer, and S. R. Holdsworth. 2003. Adaptive immunity to nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 167587-592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kyd, J. M., A. W. Cripps, L. A. Novotny, and L. O. Bakaletz. 2003. Efficacy of the 26-kilodalton outer membrane protein and two P5 fimbrin-derived immunogens to induce clearance of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae from the rat middle ear and lungs as well as from the chinchilla middle ear and nasopharynx. Infect. Immun. 714691-4699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lazou Ahren, I., A. Bjartell, A. Egesten, and K. Riesbeck. 2001. Lipopolysaccharide-binding protein increases toll-like receptor 4-dependent activation by nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae. J. Infect. Dis. 184926-930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee, N.-G., M. G. Sunshine, J. J. Engstrom, B. W. Gibson, and M. A. Apicella. 1995. Mutation of the htrB locus of Haemophilus influenzae nontypable strain 2019 is associated with modifications of lipid A and phosphorylation of the lipo-oligosaccharide. J. Biol. Chem. 27027151-27159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lesse, A. J., A. A. Campagnari, W. E. Bittner, and M. A. Apicella. 1990. Increased resolution of lipopolysaccharides and lipooligosaccharides utilizing tricine sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. J. Immunol. Methods 126109-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lysenko, E., A. J. Ratner, A. L. Nelson, and J. N. Weiser. 2005. The role of innate immune responses in the outcome of interspecies competition for colonization of mucosal surfaces. PLoS Pathog. 1e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lysenko, E., J. C. Richards, A. D. Cox, A. Stewart, A. Martin, M. Kapoor, and J. N. Weiser. 2000. The position of phosphorylcholine on the lipopolysaccharide of Haemophilus influenzae affects binding and sensitivity to C-reactive protein-mediated killing. Mol. Microbiol. 35234-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lysenko, E. S., J. Gould, R. Bals, J. M. Wilson, and J. N. Weiser. 2000. Bacterial phosphorylcholine decreases susceptibility to the antimicrobial peptide LL-37/hCAP18 expressed in the upper respiratory tract. Infect. Immun. 681664-1671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mannino, D. M. 2002. COPD: epidemiology, prevalence, morbidity and mortality, and disease heterogeneity. Chest 121121S-126S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McMahon, M., T. F. Murphy, J. Kyd, and Y. Thanavala. 2005. Role of an immunodominant T cell epitope of the P6 protein of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae in murine protective immunity. Vaccine 233590-3596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mogensen, T. H., S. R. Paludan, M. Kilian, and L. Ostergaard. 2006. Live Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Neisseria meningitidis activate the inflammatory response through Toll-like receptors 2, 4, and 9 in species-specific patterns. J. Leukoc. Biol. 80267-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moller, L. V., W. Timens, W. van der Bij, K. Kooi, B. de Wever, J. Dankert, and L. van Alphen. 1998. Haemophilus influenzae in lung explants of patients with end-stage pulmonary disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 157950-956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moran, A. P., M. M. Prendergast, and B. J. Appelmelk. 1996. Molecular mimicry of host structures by bacterial lipopolysaccharides and its contribution to disease. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 16105-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murphy, T. F., and L. C. Bartos. 1988. Human bactericidal antibody response to outer membrane protein P2 of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae. Infect. Immun. 562673-2679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Musser, J. M., S. J. Barenkamp, D. M. Granoff, and R. K. Selander. 1986. Genetic relationships of serologically nontypable and serotype b strains of Haemophilus influenzae. Infect. Immun. 52183-191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Neary, J. M., and T. F. Murphy. 2006. Antibodies directed at a conserved motif in loop 6 of outer membrane protein P2 of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae recognize multiple strains in immunoassays. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 46251-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Neary, J. M., K. Yi, R. J. Karalus, and T. F. Murphy. 2001. Antibodies to loop 6 of the P2 porin protein of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae are bactericidal against multiple strains. Infect. Immun. 69773-778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nichols, W. A., C. R. H. Raetz, T. Clementz, A. L. Smith, J. A. Hanson, M. R. Ketterer, M. Sunshine, and M. A. Apicella. 1997. htrB of Haemophilus influenzae: determination of biochemical activity and effects on virulence and lipooligosaccharide toxicity. J. Endotoxin Res. 4163-172. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Novotny, L. A., J. A. Jurcisek, F. Godfroid, J. T. Poolman, P. A. Denoel, and L. O. Bakaletz. 2006. Passive immunization with human anti-protein D antibodies induced by polysaccharide protein D conjugates protects chinchillas against otitis media after intranasal challenge with Haemophilus influenzae. Vaccine 244804-4811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Preston, A., R. E. Mandrell, B. W. Gibson, and M. A. Apicella. 1996. The lipooligosaccharides of pathogenic gram-negative bacteria. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 22139-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schweda, E. K., J. C. Richards, D. W. Hood, and E. R. Moxon. 2007. Expression and structural diversity of the lipopolysaccharide of Haemophilus influenzae: implication in virulence. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 297297-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sethi, S., N. Evans, B. J. Grant, and T. F. Murphy. 2002. New strains of bacteria and exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 347465-471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sethi, S., J. Maloney, L. Grove, C. Wrona, and C. S. Berenson. 2006. Airway inflammation and bronchial bacterial colonization in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 173991-998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sethi, S., and T. F. Murphy. 2001. Bacterial infection in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in 2000: a state-of-the-art review. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 14336-363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sethi, S., R. Sethi, K. Eschberger, P. Lobbins, X. Cai, B. J. Grant, and T. F. Murphy. 2007. Airway bacterial concentrations and exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 176356-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shuto, T., A. Imasato, H. Jono, A. Sakai, H. Xu, T. Watanabe, D. R. Rixter, H. Kai, A. Andalibi, F. Linthicum, Y. L. Guan, J. Han, A. C. Cato, D. J. Lim, S. Akira, and J. D. Li. 2002. Glucocorticoids synergistically enhance nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae-induced Toll-like receptor 2 expression via a negative cross-talk with p38 MAP kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 27717263-17270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shuto, T., H. Xu, B. Wang, J. Han, H. Kai, X. X. Gu, T. F. Murphy, D. J. Lim, and J. D. Li. 2001. Activation of NF-kappa B by nontypeable Hemophilus [sic] influenzae is mediated by toll-like receptor 2-TAK1-dependent NIK-IKK alpha /beta-I kappa B alpha and MKK3/6-p38 MAP kinase signaling pathways in epithelial cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 988774-8779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Swords, W. E., B. Buscher, K. Ver Steeg, W. Nichols, A. Preston, J. N. Weiser, B. Gibson, and M. A. Apicella. 2000. Nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae adhere to and invade human bronchial epithelial cells by an interaction of lipooligosaccharide with the PAF receptor. Mol. Microbiol. 3713-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Swords, W. E., D. L. Chance, L. A. Cohn, J. Shao, M. A. Apicella, and A. L. Smith. 2002. Acylation of the lipooligosaccharide of Haemophilus influenzae and colonization: an htrB mutation diminishes the colonization of human airway epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 704661-4668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Swords, W. E., P. A. Jones, and M. A. Apicella. 2003. The lipooligosaccharides of Haemophilus influenzae: an interesting assortment of characters. J. Endotoxin Res. 9131-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Swords, W. E., M. R. Ketterer, J. Shao, C. A. Campbell, J. N. Weiser, and M. A. Apicella. 2001. Binding of the nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae lipooligosaccharide to the PAF receptor initiates host cell signaling. Cell. Microbiol. 8525-536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Swords, W. E., M. L. Moore, L. Godzicki, G. Bukofzer, M. J. Mitten, and J. VonCannon. 2004. Sialylation of lipooligosaccharides promotes biofilm formation by nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae. Infect. Immun. 72106-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Takeuchi, O., K. Hoshino, and S. Akira. 2000. Cutting edge: TLR2-deficient and MyD88-deficient mice are highly susceptible to Staphylococcus aureus infection. J. Immunol. 1655392-5396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Toews, G. B., J. A. Hart, and E. J. Hansen. 1985. Effect of systemic immunization on pulmonary clearance of Haemophilus influenzae type b. Infect. Immun. 48343-349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Toews, G. B., S. Viroslav, D. A. Hart, and E. J. Hansen. 1984. Pulmonary clearance of encapsulated and unencapsulated Haemophilus influenzae strains. Infect. Immun. 45437-442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tong, H. H., L. E. Blue, M. A. James, Y. P. Chen, and T. F. DeMaria. 2000. Evaluation of phase variation of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae lipooligosaccharide during nasopharyngeal colonization and development of otitis media in the chinchilla model. Infect. Immun. 684593-4597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tsai, C.-M., and C. E. Frasch. 1982. A sensitive silver stain for detecting lipopolysaccharides in polyacrylamide gels. Anal. Biochem. 119115-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang, B., D. J. Lim, J. Han, Y. S. Kim, C. B. Basbaum, and J.-D. Li. 2002. Novel cytoplasmic proteins of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae up-regulate human MUC5AC mucin transcription via a positive p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway and a negative phosphoinositide 3-kinase-Akt pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 277949-957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang, X., C. Moser, J. P. Louboutin, E. S. Lysenko, D. J. Weiner, J. N. Weiser, and J. M. Wilson. 2002. Toll-like receptor 4 mediates innate immune responses to Haemophilus influenzae infection in mouse lung. J. Immunol. 168810-815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Weiser, J. N. 2000. The generation of diversity by Haemophilus influenzae. Trends Microbiol. 8433-435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Weiser, J. N., and N. Pan. 1998. Adaptation of Haemophilus influenzae to acquired and innate humoral immunity based on phase variation of lipopolysaccharide. Mol. Microbiol. 30767-775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Weiser, J. N., N. Pan, K. L. McGowan, D. Musher, A. Martin, and J. Richards. 1998. Phosphorylcholine on the lipopolysaccharide of Haemophilus influenzae contributes to persistence in the respiratory tract and sensitivity to serum killing mediated by C-reactive protein. J. Exp. Med. 187631-640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Weiser, J. N., M. Shchepetov, and S. T. Chong. 1997. Decoration of lipopolysaccharide with phosphorylcholine: a phase-variable characteristic of Haemophilus influenzae. Infect. Immun. 65943-950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Weiss, D. S., B. Raupach, K. Takeda, S. Akira, and A. Zychlinsky. 2004. Toll-like receptors are temporally involved in host defense. J. Immunol. 1724463-4469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.West-Barnette, S., A. Rockel, and W. E. Swords. 2006. Biofilm growth increases phosphorylcholine content and decreases potency of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae endotoxins. Infect. Immun. 741828-1836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wieland, C. W., S. Florquin, N. A. Maris, K. Hoebe, B. Beutler, K. Takeda, S. Akira, and T. van der Poll. 2005. The MyD88-dependent, but not the MyD88-independent, pathway of TLR4 signaling is important in clearing nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae from the mouse lung. J. Immunol. 1756042-6049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yi, K., S. Sethi, and T. F. Murphy. 1997. Human immune response to nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae in chronic bronchitis. J. Infect. Dis. 1761247-1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]