Abstract

Secretion of effector molecules is one of the major mechanisms by which the intracellular human pathogen Legionella pneumophila interacts with host cells during infection. Specific secretion machineries which are responsible for the subfraction of secreted proteins (soluble supernatant proteins [SSPs]) and the production of bacterial outer membrane vesicles (OMVs) both contribute to the protein composition of the extracellular milieu of this lung pathogen. Here we present comprehensive proteome reference maps for both SSPs and OMVs. Protein identification and assignment analyses revealed a total of 181 supernatant proteins, 107 of which were specific to the SSP fraction and 33 of which were specific to OMVs. A functional classification showed that a large proportion of the identified OMV proteins are involved in the pathogenesis of Legionnaires' disease. Zymography and enzyme assays demonstrated that the SSP and OMV fractions possess proteolytic and lipolytic enzyme activities which may contribute to the destruction of the alveolar lining during infection. Furthermore, it was shown that OMVs do not kill host cells but specifically modulate their cytokine response. Binding of immunofluorescently stained OMVs to alveolar epithelial cells, as visualized by confocal laser scanning microscopy, suggested that there is delivery of a large and complex group of proteins and lipids in the infected tissue in association with OMVs. On the basis of these new findings, we discuss the relevance of protein sorting and compartmentalization of virulence factors, as well as environmental aspects of the vesicle-mediated secretion.

Legionella pneumophila is an intracellular human pathogen that can cause a severe form of pneumonia. This gram-negative bacterium naturally inhabits freshwaters, where it parasitizes protozoan hosts. After aerosol formation in man-made water systems, L. pneumophila can enter and colonize the human lung (74). Chest radiographs typically show patchy, peripheral, nonsegmental consolidations. Electron microscopy shows L. pneumophila within macrophages and neutrophils, and it is well documented that the bacteria multiply within a reprogrammed Legionella-specific vacuole. The host cell lysis caused by the pathogen may be so prominent that the alveolar exudate appears acellular. In many cases diffuse alveolar damage can be observed even at sites other than the active pneumonia sites (75, 82).

During infection L. pneumophila employs sophisticated machineries to deliver proteins to cellular and extracellular locations. In particular, the Dot/Icm type IV secretion system and the Lsp type II secretion system are known to contribute to virulence. Dot/Icm type IV secretion is required for the establishment of the intracellular replicative niche of L. pneumophila in protozoans and human macrophages (5, 58, 72). Recently, several transported effector proteins have been identified. Among these proteins are DrrA/SidM, LepA, LepB, LidA, RalF, and SidA-H (19, 24, 50, 51, 56, 57). The Lsp type II secretion system also promotes intracellular infection of protozoans and human alveolar cells (22, 65, 66). It is involved in the secretion of acid phosphatases, an RNase, the zinc metalloprotease Msp (ProA1), a chitinase, mono-, di-, and triacylglycerol lipases, phospholipases A and C, the lysophospholipase A PlaA, the lysophospholipase A homolog PlaC, and a p-nitrophenyl phosphorylcholine hydrolase (6, 7, 10, 26, 33, 40, 65). Recent genome analysis revealed additional secretion systems, including a second type IV secretion system (the Lvh system), a type I secretion pathway encoded by the lssXYZABD locus, a twin-arginine translocation pathway, and several Tra-like systems (4).

Besides the secretion of individual proteins, many gram-negative bacteria, including L. pneumophila, shed vesicles derived from the outer membrane (29). In general, outer membrane vesicles (OMVs) are spherical bilayer structures and consist of characteristic outer membrane constituents, such as phospholipids, lipopolysaccharide (LPS), and a subset of outer membrane proteins. The vesicle lumen contains mainly periplasmic components (14, 48). Since OMVs are used by gram-negative bacteria to deliver proteins to the extracellular environment and into host cells, the term “vesicle-mediated secretion” has been coined (45, 79).

Previous studies have shown that L. pneumophila produces OMVs (31, 64). More recently, it has been demonstrated that OMVs can inhibit phagosome-lysosome fusion and that this phenomenon correlates with developmentally regulated modifications of the LPS profile (29). In the present study we performed the first comprehensive proteome comparison of proteins secreted by different secretion systems (soluble supernatant proteins [SSPs]) and the OMV fraction of proteins of L. pneumophila. Using a functional approach, we analyzed destructive enzyme activities, alteration of cytokine profiles, host cell killing, and binding of OMVs to host cells, which are critical activities during the Legionella-host interaction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

The genetically tractable and highly virulent L. pneumophila Philadelphia-1 strain JR32 (67, 68) was grown either on buffered charcoal-yeast extract (BCYE) agar (28) or in yeast extract broth (YEB) on an orbital shaker at 37°C (46).

Cell cultures and conditions.

Acanthamoeba castellanii ATCC 33152 was cultured in proteose peptone-yeast extract-glucose (PYG) medium at room temperature, and Dictyostelium discoideum wild-type strain AX2 amoebae were grown in HL5 medium at 23°C as described previously (39).

A549 (CCL-185) and NCI-H292 (CRL-1848) human type II alveolar epithelial cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection and were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium containing 2 mM l-glutamine and 10% fetal calf serum (RPMI/FCS) according to the supplier's instructions.

Fractionation of bacterial culture supernatants.

Fractionation of supernatants was performed using bacterial liquid cultures in early stationary growth phase (optical density at 600 nm, 1.8) to reduce cytoplasmic contamination by broken cells. After bacteria were removed by centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C, the supernatants were filtered through a 0.22-μm vacuum filter. OMVs were then separated using the protocol of Wai et al. (79), starting with centrifugation at 150,000 × g for 3 h at 4°C in a 45 Ti rotor (Beckman Coulter, Krefeld, Germany). The remaining liquid was used as the SSP fraction. The pellets obtained were suspended in 0.02 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) and filtered through 0.22-μm syringe-driven sterile filters. Finally, the suspensions were concentrated with Centricon centrifugal filter units (Millipore, Schwalbach, Germany) and used as the OMV fraction. To test comparable amounts of OMVs, the total protein content per microliter of OMV fractions was determined by using the Roti-Nanoquant reagent according to the protocol recommended by the manufacturer (Roth). Bovine serum albumin was used as the standard protein.

Electron microscopy.

Thin-section microscopy of L. pneumophila-infected D. discoideum was performed as described by Hägele et al. (39). Negative staining was carried out using an aqueous solution of 0.5% uranyl acetate. Portions (5 μl) of OMV fractions or bacterial suspensions in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) were allowed to sediment on copper grids (Provac) coated with thin films of 0.6% polioform in chloroform. Then the grids were rinsed with filtered (0.22 μm) ultrapure water (Millipore). After staining, the grids were rinsed again and examined with a Zeiss A100 transmission electron microscope.

Atomic force microscopy.

For atomic force microscopy OMV fractions and bacterial suspensions were diluted with filtered (0.22 μm) ultrapure water (Millipore). Portions (10 μl) of diluted samples were placed onto a freshly cleaved mica surface (Goodfellow) and incubated at room temperature for 5 min. Then the samples were gently rinsed with filtered ultrapure water, excessive liquid was absorbed at the edges, and the samples were dried in a desiccator overnight. Imaging was performed with a Nanoscope IIIa atomic force microscope (Digital Instruments) using the tapping mode. Standard silicon cantilevers (Digital Instruments) were used.

Protein preparation for 2-DE.

For two-dimensional gel electrophoresis (2-DE), 600-μl supernatant fractions were used. The vesicles in OMV fractions were dissolved by treatment with 30 μl of 0.5% Triton X-100 for 25 min on ice. After centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C, the supernatants were transferred to new test tubes and diluted 10-fold with ultrapure water. The following steps were performed for both OMV and SSP fractions. Proteins were precipitated overnight with ice-cold trichloroacetic acid at a final concentration of 10% and collected by centrifugation at 6,000 × g for 1 h at 4°C. The resulting protein pellets were washed five times with 96% ethanol and then dried at room temperature. Finally, the protein pellets were resolved in a 200-μl solution containing 8 M urea and 2 M thiourea. Protein concentrations were determined by using the Roti-Nanoquant reagent.

Preparative 2-DE, two-dimensional difference gel electrophoresis, and data analysis.

For preparative 2-DE, 500-μg portions of SSP or OMV protein preparations were used. The volumes of samples were adjusted with rehydration solution, which contained 2 M thiourea, 7 M urea, 4% 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)-dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPS), 200 mM dithiothreitol, and 10% pharmalytes 3-10, to 450 μl. Isoelectric focusing was performed using the IPG technique with nonlinear 24-cm IPG strips (pH 3 to 10) and a Multiphor II unit (GE Healthcare). The 12.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) in the second dimension was performed with an Ettan DALT six electrophoresis unit (GE Healthcare) used according to the manufacturer's instructions. The resulting two-dimensional gels were stained using the colloidal Coomassie brilliant blue G-250 procedure as previously described (12). For comparative analysis of SSP and OMV protein patterns, difference gel electrophoresis minimal labeling experiments were carried out as recommended by the manufacturer (GE Healthcare). Subsequently, gels were scanned with a Typhoon imager (GE Healthcare). At least two different gel sets from fractions of two independent bacterial culture supernatants were analyzed. Two-dimensional gel image analysis was performed with the Delta 2-D 3.2 software (Decodon).

Protein identification and in silico analysis.

Proteins were excised from Coomassie brilliant blue-stained two-dimensional gels using a Proteome Works spot cutter (Bio-Rad). Trypsin digestion and subsequent spotting of peptide solutions onto matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization (MALDI) targets were performed automatically using an Ettan spot handling workstation (GE Healthcare) and a modified standard protocol (27). MALDI-time of flight (TOF) mass spectrometry (MS) analyses of spotted peptide solutions were carried out using a 4700 proteome analyzer (Applied Biosystems) as described by Eymann et al. (27).

The resulting peptide mass fingerprints were analyzed using the MASCOT search engine (Matrix Science) and the genome sequence of L. pneumophila Philadelphia-1 available at http://legionella.cu-genome.org/ (21). Identified proteins were sorted according to KEGG pathway maps for L. pneumophila Philadelphia-1 available at http://www.genome.ad.jp/kegg/ (43). Proteins not listed were grouped manually by referring to their functions. Proteins containing eukaryote-like domains, proteins with homology to known virulence factors, and proteins that make putative or known contributions to L. pneumophila pathogenesis were sorted into a separate class. Predictions of protein localization were made by using PA-SUB (49) and PSORTb or the PSORTdb L. pneumophila Philadelphia-1 data set available at http://db.psort.org/ (38, 63). PSORTb was also used to predict signal peptides. Finally, theoretical results were expanded by manually searching localizations described previously.

Zymography.

Proteolytic activities of bacterial culture supernatants and SSP and OMV fractions were detected by using SDS-gelatin-polyacrylamide gels and the method of Heussen and Dowdle (41), with slight modifications. Samples without reducing agents were separated on 12% SDS-PAGE minigels containing 0.2% gelatin (type B from bovine skin; Sigma). After electrophoresis, the gels were washed twice at room temperature with 2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 30 min and then incubated at 37°C in PBS overnight. Finally, proteolytic activities were identified by Coomassie blue staining.

Enzyme assays.

All enzyme assay mixtures were processed using specifically modified substrates which colored the test solution after cleavage. Protease activity was determined by using hide powder azure (Sigma) as described by Howe and Iglewski (42). Elastase activity was detected by an assay based on the method of Kessler et al. (44), utilizing elastin Congo red (Sigma). Lipolytic activities were examined by using p-nitrophenyl palmitate (NPP) and p-nitrophenyl phosphorylcholine (NPPC) (Sigma), as described by Aragon et al. (7, 8).

In all cases OMV fractions, bacterial culture supernatants, and SSP fractions were assayed. YEB, 0.02 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), and PBS served as negative controls. Each sample was analyzed in duplicate. The means and standard deviations were calculated from at least three separate experiments.

Growth inhibition assays.

To study the effect on growth of A. castellanii and alveolar epithelial cell cultures, the Alamar blue assay was used (3, 54). The concentrations of A. castellanii and alveolar epithelial cell suspensions were adjusted to 1 × 105 and 6 × 104 cells per ml, respectively. To each well 180 μl PYG medium or RPMI/FCS containing various amounts of OMVs and then 20 μl of the corresponding cell suspension were added. As blanks we used 200 μl PYG medium and RPMI/FCS, respectively. After 24 h of incubation at room temperature and at 37°C (5% CO2), respectively, 20 μl Alamar blue was added to each well. Alamar blue reduction was measured after 24, 48, and 72 h of incubation by determining the absorbance at 550 and 630 nm with a Multiskan ascent plate reader (Thermo). Growth curves for cell densities were analyzed with Excel (Microsoft) by subtracting the absorbance at 550 nm from the absorbance at 630 nm. All tests of OMV fractions were performed at least in triplicate.

In order to exclude apoptotic effects by OMVs, 1 × 105 cells were fixed in freshly prepared paraformaldehyde (3% paraformaldehyde in PBS, pH 7.6), permeabilized, and washed, and DNA strand breaks were labeled by terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated fluorescein-dUTP nick end labeling and analyzed by using an LSM 510 confocal laser scanning microscope (Zeiss).

Confocal laser scanning microscopy.

Confocal laser scanning microscopy analysis of OMV binding to alveolar epithelial cells was carried out as described by Agerer et al. (1, 2), with some modifications. A549 cells were seeded on glass coverslips in 24-well plates (coated with a mixture of fibronectin and poly-l-lysine in PBS [final concentration of each compound, 2 μg/ml]) in cell culture medium 1 day before binding experiments were performed. Then different doses of OMVs in serum-free medium were applied to cells for 8 h at 37°C. After incubation, cells were washed once with PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min at room temperature. Then samples were washed again with PBS and blocked with 10% fetal calf serum in PBS (blocking buffer) for 5 min at room temperature. Subsequently, OMVs were stained with the mouse anti-LPS monoclonal antibody 2F10 (Acris Antibodies, Herford, Germany) in blocking buffer for 45 min at room temperature. Samples were washed twice with PBS, blocked again for 5 min, and incubated with a mixture of Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G and wheat germ agglutinin (WGA)-Alexa Fluor 594 (Molecular Probes) for 45 min at room temperature. After three washes with PBS, coverslips were mounted in embedding medium (Dako) on glass slides and sealed with nail polish. Samples were viewed with an LSM 510 confocal laser scanning microscope (Zeiss). Fluorescence signals of double-labeled specimens were serially recorded with appropriate excitation and emission filters to avoid bleed-through. Images were digitally processed with Photoshop (Adobe Systems) and merged to obtain pseudocolored pictures.

Cytokine profiling.

Cytokine profiles were determined using the Bioplex protein array system (Bio-Rad). Confluent A549 cells were stimulated with OMV fractions for 15 h (71). After incubation, cell supernatants were collected and cleared by centrifugation. Cytokine release was examined with Bioplex beads specific for interleukin-1β (IL-1β), IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12 (p70), IL-13, IL-17, monocyte chemoattractant protein 1, tumor necrosis factor alpha, gamma interferon (IFN-γ), granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor used according to the instructions of the manufacturer. To exclude protease-induced cytokine stimulation, additional treatments with 100 μM phosphoramidon and complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor (71 μl per 0.5-ml sample) were tested in control experiments. The data are expressed below as means ± standard deviations of at least three independent experiments. Main effects were compared using the Newman-Keuls posttest. A P value of <0.01 was considered significant.

RESULTS

L. pneumophila produces OMVs during extra- and intracellular growth.

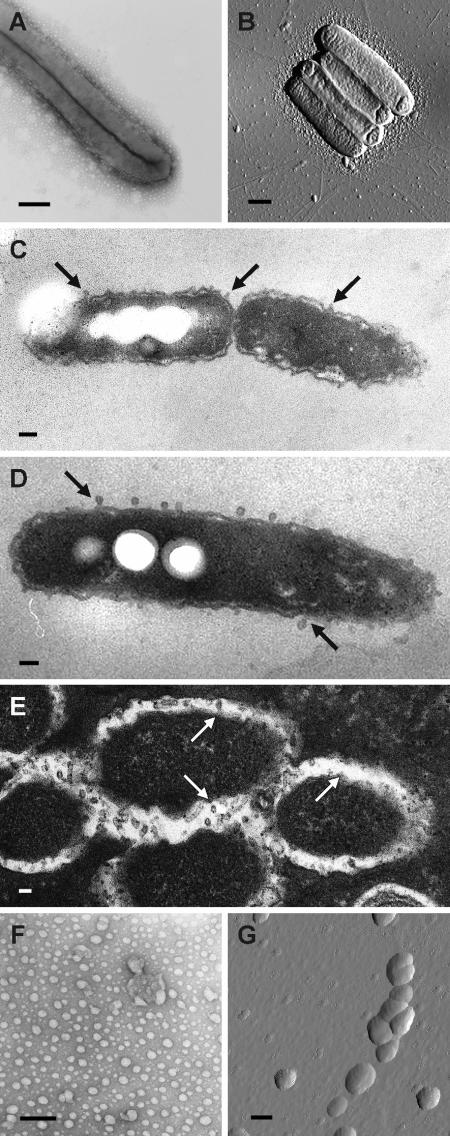

To analyze whether OMV production occurs throughout the L. pneumophila life cycle, we performed microscopic studies after different time intervals (24, 48, and 72 h of cultivation) and using different growth conditions (extra- and intracellular growth). Bacterial cells were removed from BCYE agar, processed as described in Materials and Methods, and analyzed by negative staining electron microscopy and atomic force microscopy (Fig. 1A and B). All cells examined were surrounded by multiple OMVs during the logarithmic and stationary phases of bacterial growth. Figures 1C and D show representative electron micrographs of thin sections of extracellular L. pneumophila cells from a logarithmic culture and a stationary culture. In both growth phases the bacteria produced discrete OMVs that were released from the intact bacterial membrane, indicating that the vesicles were not the result of bacterial cell lysis. Thin-section electron microscopy after 24 h of coincubation of L. pneumophila and D. discoideum revealed small blebs that appeared to be budding from the L. pneumophila membrane surface within the Legionella-specific phagosome of infected D. discoideum host cells (Fig. 1E). The secretion of OMVs inside the host phagosome is in agreement with the recent observation that L. pneumophila OMVs inhibit phagosome-lysosome fusion (29). Thus, the data indicate that OMVs are produced extra- and intracellularly under different growth conditions and during different growth phases.

FIG. 1.

L. pneumophila secretes OMVs when it is growing under extra- and intracellular conditions. (A and B) Secretion of OMVs by L. pneumophila grown on solid medium (BCYE agar) analyzed by negative staining electron microscopy (A) and atomic force microscopy (B). Bars = 0.5 μm. (C and D) Production of OMVs by L. pneumophila during the logarithmic phase (C) and stationary phase (D) of extracellular growth. Samples were analyzed by thin-section electron microscopy. The arrows indicate OMVs budding off the membrane surface. Bars = 0.5 μm (C) and 0.2 μm (D). (E) OMV production by intracellular L. pneumophila: thin-section microscopy showing Legionella-specific phagosomes of infected D. discoideum host cells. The arrows indicate OMV budding sites on the membrane surface. Bar = 0.2 μm. (F and G) OMVs were isolated from bacterial liquid cultures (YEB) using our purification protocol and were visualized by negative staining electron microscopy (F) and atomic force microscopy (G). Bars = 0.2 μm.

To obtain highly purified, native L. pneumophila OMVs, we developed a purification method based on previously described protocols using ultracentrifugation. The purified OMV fraction from bacterial liquid cultures in early stationary growth phase was analyzed by negative staining electron microscopy and atomic force microscopy (Fig. 1F and G). The diameters of isolated OMVs ranged from 100 to 200 nm, and the absence of bacterial debris and other structures, like flagella, confirmed the purity of our OMV fraction.

OMV and SSP subfractions have specific protein compositions.

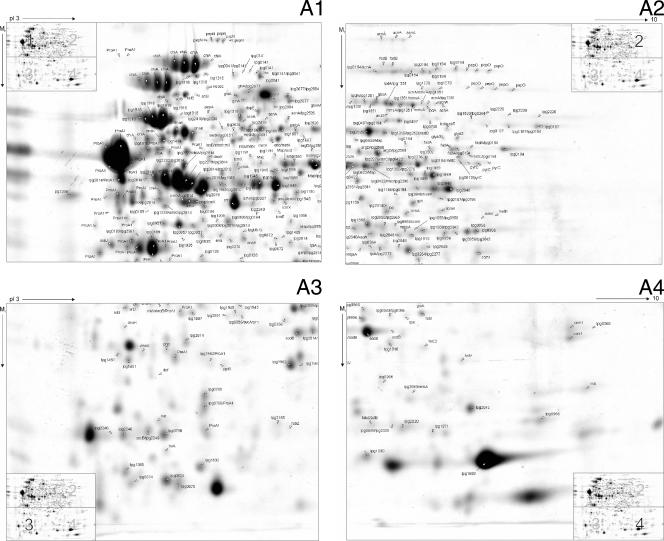

OMVs are generated by budding from the outer membrane of the bacterium, whereas SSPs are the result of secretion systems in which proteins are exported from the cytoplasm across the inner and outer membranes into the exterior space. To map the subfraction proteomes, SSP and OMV fractions were prepared from early-stationary-phase cultures of highly virulent L. pneumophila Philadelphia-1 bacteria and separated by preparative 2-DE. Subsequently, all visible protein spots were subjected to MALDI-TOF MS analysis. Figure 2 shows the L. pneumophila proteome reference maps constructed for the SSP and OMV fractions. A total 336 protein spots of the SSP fraction, representing 148 nonredundant proteins, were identified by MS. Moreover, we identified 74 distinct proteins in 157 OMV protein spots analyzed. Several proteins produced more than one spot due to pI or mass variations. In some cases a protein was dispersed as multiple spots. A total of 181 different L. pneumophila proteins were unambiguously assigned to the supernatant, including 107 SSPs (59%), 33 OMV proteins (18%), and 41 proteins which appeared in both fractions (23%). A detailed list of all identified proteins, which represents the largest validated secretome profile of this organism, shown in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

FIG. 2.

Proteome reference maps of L. pneumophila supernatant subfractions. (A) SSP fraction. The two-dimensional reference map is divided into the following four sections: panel 1, upper left section (high Mr and low pI); panel 2, upper right section (high Mr and high pI); panel 3, lower left section (low Mr and low pI); and panel 4, lower right section (low Mr and high pI). (B) Two-dimensional reference map of the OMV fraction. Isolated protein fractions were focused on pH 3 to 10 IPG strips and separated by SDS-PAGE second-dimension gels. Gels were stained with Coomassie brilliant blue G-250. Proteins were identified following tryptic digestion and analysis of the resulting peptides by MALDI-TOF MS. Gene designations in the L. pneumophila Philadelphia-1 database (http://legionella.cu-genome.org/) are indicated. All MS-identified proteins are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

To assess the identified proteins, we calculated the localization of L. pneumophila proteins using two independent programs, PSORTb and PA-SUB. The theoretical results were compared with localizations experimentally observed in previous studies. Both fractions consisted of extracellular, outer membrane, periplasmic, inner membrane, and cytosolic proteins. As expected, the majority of detected periplasmic and outer membrane proteins were associated with OMVs, whereas the SSP fraction contained a higher number of extracellular proteins (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Only 31 of 181 identified proteins (17%) were predicted to be cytoplasmic by both programs. This proportion is low compared to previous studies of OMV proteomes (30, 80) and might have been the result of some cell lysis or cell autolysis that occurred during bacterial growth (76). When the list of proteins was searched, many type II and type IV secretion substrates were discovered. Of 27 type II substrates recently described by DebRoy and colleagues (26), we identified 22 during our analysis (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Only LvrE (lpg1244) and four hypothetical proteins were not found. Consistently, most detected type II substrates were localized in the SSP fraction; the only exception was flagellin, which was found exclusively in OMVs. Some of the type II substrates were also OMV associated. According to the in silico screen for putative type II substrates performed by DebRoy and colleagues (26), 38 of these substrates were in fact detected in the supernatant. Furthermore, three type IV substrates, LaiE (lpg2154), SdeD (LaiF) (lpg2509), and WipC (lpg2206), were found in the OMV and SSP fractions (16, 59). The lack of some predicted or known extracellular, outer membrane, and periplasmic proteins, as well as secretion substrates, might have resulted from the problematic MS identification of low-molecular-mass proteins, low abundance, or the lack of expression of certain proteins under the growth conditions used (e.g., artificial growth medium, no host cell contact, etc.) (20). Based on the KEGG GENES database and an extensive literature search, we classified the identified proteins into the 21 functional groups shown in Table S2 in the supplemental material. Interestingly, the most entries were found for the following classes: involved in pathogenesis, amino acid metabolism, carbohydrate metabolism, energy metabolism, and protein folding, sorting, and degradation. In general, the proportions of the groups were slightly higher for the SSP fraction than for the OMV fraction except for the virulence/pathogenesis functional class. The latter class contains 25 (14%) of the 181 supernatant proteins overall. In contrast to the 11% of the proteins (17 of 148 proteins) in the SSP fraction, 24% (18 of 74) of the OMV proteins were associated with pathogenesis. Moreover, the virulence factor Mip (lpg0791) was found only in the OMV fraction (46). Thus, OMVs may be vehicles for the delivery of bacterial virulence factors (Table 1; see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

TABLE 1.

Secretome proteins that make putative or confirmed contributions to L. pneumophila virulence identified by 2-DE analysis

| 2-DE analysisa

|

GenInfo Identifier no.b | Identity (as defined in the genome)c | Gene designation ind:

|

Characteristics | Reference(s) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OMV | SSP | Philadelphia-1 | Lens | Paris | ||||

| + | 52840695 | IcmK (DotH) | lpg0450 | lpl0492 | lpp0516 | Part of core transmembrane complex (type IV secretion system) | 77 | |

| + | 52841028 | mip; macrophage infectivity potentiator (Mip) | lpg0791 | lpl0829 | lpp0855 | Peptidyl-prolyl isomerase domain; protein-protein interaction; promotes phospholipase C activity and transmigration through lung epithelial cells | 25, 78 | |

| + | 52841206 | Ecto-ATP diphosphohydrolase II | lpg0971 | lpl1000 | lpp1033 | Eukaryote-like; eukaryotic GDA1/CD39 NTPDase family homolog; phosphoesterase/phosphatase | 69 | |

| + | 52841570 | fliC; flagellin | lpg1340 | lpl1293 | lpp1294 | Flagellar assembly; involved in evasion and spreading; type II secreted | 26 | |

| + | 52841685 | Phospholipase C | lpg1455 | lpl1573 | lpp1411 | Phospholipase; plcB homolog | 26 | |

| + | 52842368 | LaiE | lpg2154 | lpl2082 | lpp2093 | SidE paralog; type IV secreted | 16 | |

| + | 52842717 | SdeD (LaiF) | lpg2509 | lpl2431 | lpp2577 | SidE paralog; type IV secreted | 16 | |

| + | 52843033 | Phospholipase/lecithinase/hemolysin, lysophospholipase A | lpg2837 | lpl2749 | lpp2894 | Phospholipase; plaC homolog | 10, 26 | |

| + | + | 52840696 | IcmE (DotG) | lpg0451 | lpl0493 | lpp0517 | Part of core transmembrane complex (type IV secretion system) | 77 |

| + | + | 52840712 | Zinc metalloprotease (ProA1, Msp) | lpg0467 | lpl0508 | lpp0532 | Protease/peptidase; contributes to tissue damage in vivo; type II secreted | 26, 55, 66 |

| + | + | 52840747 | Phosphatidylcholine-hydrolyzing phospholipase | lpg0502 | lpl0541 | lpp0565 | Phospholipase; plcA homolog | 8, 26 |

| + | + | 52840925 | htpB; Hsp60, 60-kDa heat shock protein HtpB | lpg0688 | lpl0724 | lpp0743 | GroEL chaperonin family member; protein-protein interaction; involved in adherence and invasion | 37 |

| + | + | 52841350 | Chitinase (ChiA) | lpg1116 | lpl1121 | lpp1117 | Glycosylase; promotes persistence in the lung; type II secreted | 26 |

| + | + | 52841353 | Major acid phosphatase (Map) | lpg1119 | lpl1124 | lpp1120 | Eukaryote-like; phosphoesterase/phosphatase; type II secreted | 26 |

| + | + | 52842435 | TPR repeat protein, protein-protein interaction | lpg2222 | lpl2147 | lpp2174 | Eukaryote-like; lpnE homolog (enhC-like) | 26 |

| + | + | 52842850 | sclB; tail fiber protein | lpg2644 | lpl2569 | lpp2697 | Eukaryote-like; domain homology to type VI collagen; type II secreted | 26, 70 |

| + | + | 52842895 | IcmX (IcmY) | lpg2689 | lpl2616 | lpp2743 | Involved in type IV secretion; required for biogenesis of the replicative organelle; type II secreted | 26, 53 |

| + | + | 52843192 | legP; astacin protease | lpg2999 | lpl2927 | lpp3071 | Eukaryote-like; astacin protease; type II secreted | 26, 73 |

| + | 52840667 | legY; amylase | lpg0422 | lpl0465 | lpp0489 | Eukaryote-like; amylase | 73 | |

| + | 52840945 | IcmL-like | lpg0708 | lpl0745 | lpp0763 | Putatively involved in type IV secretion | 77 | |

| + | 52841883 | lasB; class 4 metalloprotease (elastase) | lpg1655 | lpl1620 | lpp1626 | ProA-like protease/peptidase | ||

| + | 52842236 | Serine metalloprotease | lpg2019 | lpl1996 | lpp2001 | Protease/peptidase | ||

| + | 52842419 | WipC | lpg2206 | lpl2131 | lpp2157 | IcmW-interacting protein; type IV secreted | 16 | |

| + | 52842553 | sseJ; lysophospholipase A | lpg2343 | lpl2264 | lpp2291 | Phospholipase; plaA homolog; type II secreted | 26, 33 | |

| + | 52842794 | legS1; lipid phosphoesterase | lpg2588 | lpl2511 | lpp2641 | Eukaryote-like; signaling lipid related domain; lipid phosphoesterase | 73 | |

+, present in supernatant OMV or SSP subfraction in this study.

GenInfo Identifier numbers in the NCBI protein sequence database.

Identities based on the genome annotation of L. pneumophila Philadelphia-1 (http://legionella.cu-genome.org/).

Gene designations for the three sequenced strains, L. pneumophila Philadelphia-1, Lens, and Paris (http://legionella.cu-genome.org/ and http://genolist.pasteur.fr/LegioList/).

Taken together, the results of the proteome mapping demonstrated that a large proportion of proteins are specific for either the SSP fraction or the OMV fraction. Moreover, a higher number of virulence-associated proteins are present in the OMV fraction than in the SSP fraction.

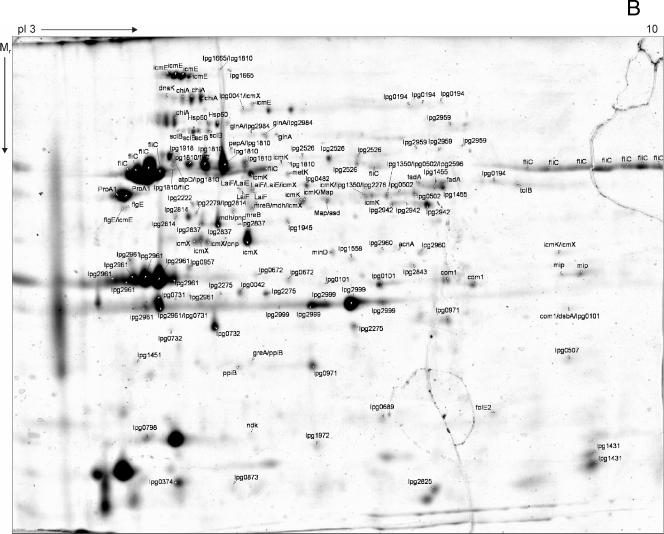

SSP and OMV fractions possess diverse destructive enzyme activities.

During infection L. pneumophila penetrates the alveolar lining and basement membrane (11, 78). Moreover, focal septal disruption, invasion of the interstitium, and extrapulmonary manifestations are characteristic features (78, 83). Hence, degradative enzymes are likely to be required to perforate tissue barriers. Therefore, we performed proteolytic and lipolytic assays with OMV and SSP fractions to detect destructive enzyme activities. First, proteolytic activities of OMV, SSP, bacterial culture supernatant, and whole-cell subfractions were analyzed by degradation zymography. For this purpose, gelatin, which consists of the extracellular matrix proteins collagens I, II, and III, was used. Prominent proteolytic bands at approximately 40 kDa and light bands at high molecular weights (100 to 200 kDa) demonstrated that activities were present in OMV, SSP, and supernatant samples (Fig. 3A). The prominent proteolytic bands might have been produced by ProA1 (Msp) (lpg0467), which was found to be one of the most abundant proteins (Fig. 2). The light bands might have been the result of multiple aggregations due to the nonreducing conditions used. Second, we analyzed the protease activities of the different subfractions by using a liquid assay with the synthetic substrate hide powder azure blue. Again, the OMV, SSP, and supernatant fractions exhibited proteolytic activities in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3B). The removal of OMVs from the bacterial culture supernatant, which resulted in the SSP fraction, reduced the enzymatic activity only slightly. Nevertheless, the OMV fraction exhibited significant enzymatic activity. This, however, suggests that the majority of the proteolytic activity is located in the SSP fraction. Third, similar results were obtained for the elastase-specific protease substrate elastin Congo red (data not shown). Finally, to investigate lipolytic activities, we used two different substrates, NPP for esterase-lipase and NPPC for lipase activity. As shown in Fig. 3C, OMVs and SSPs cleaved both lipase substrates efficiently. Again, it was obvious that the majority of the enzymatic activity was associated with the SSP fraction. When the results were taken together, by using various enzyme assays we confirmed that both the SSP and OMV fractions contained enzyme activities which may contribute to destruction of the alveolar lining.

FIG. 3.

L. pneumophila SSP and OMV fractions degrade protease and lipase substrates. (A) Protease activities detected by zymography with gelatin (from bovine skin). White clearing zones indicate gelatin degradation. (B) Proteolytic activities analyzed in a liquid assay using hide powder azure. The dotted line separates OMV samples, as the amounts tested are not comparable to the amounts in other samples. (C) Lipolytic activities determined by cleavage of the synthetic substrates NPP (□) and NPPC (▪). Again, the dotted line separates OMV samples, as the amounts examined were not comparable to other amounts. SN, bacterial culture supernatant; WC, whole bacterial cells; tp, total protein content per microliter of OMV fraction. The data are means and standard deviations of at least three independent experiments. A P value of <0.01 was considered significant.

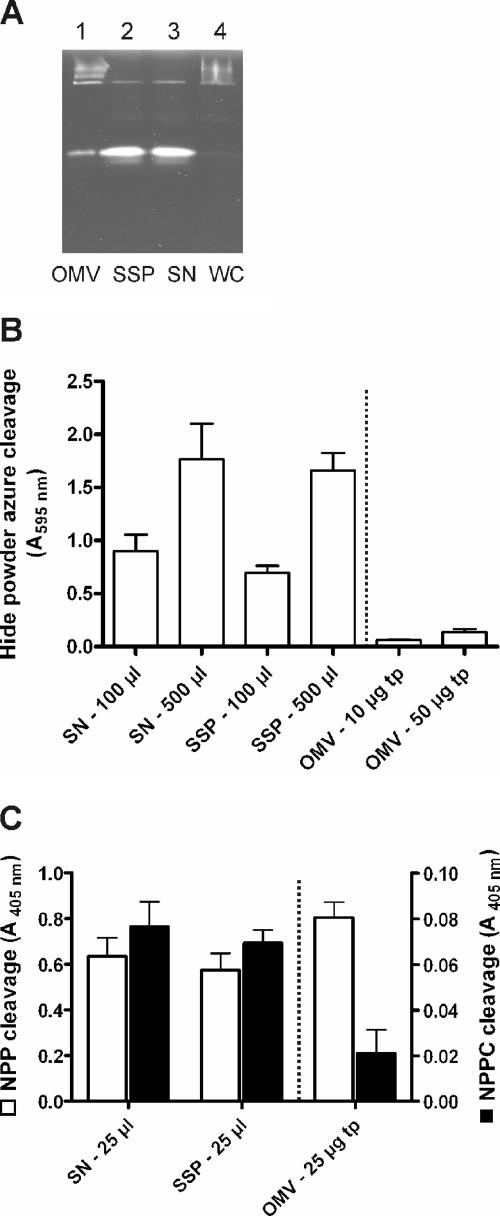

OMVs do not kill host cells but promote A. castellanii growth.

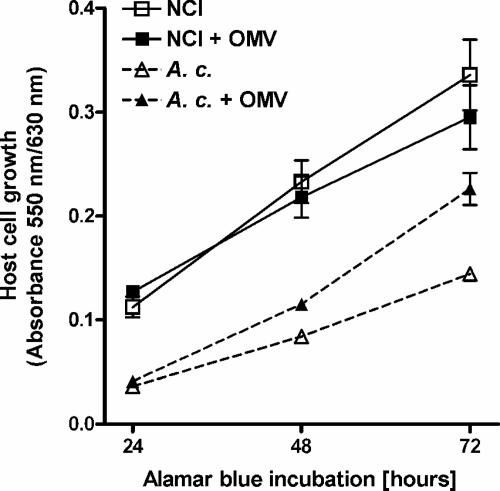

To investigate whether OMV fractions kill human alveolar epithelial and protozoan cells that are host cells of L. pneumophila, we performed Alamar blue assays. After 72 h of incubation, the growth of alveolar epithelial cells was slightly but not significantly reduced (Fig. 4). Terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated fluorescein-dUTP nick end labeling assays with alveolar epithelial cells additionally helped to exclude apoptotic effects by OMVs (data not shown). More strikingly, however, was the observation that OMVs promoted the growth of the protozoan host A. castellanii by 64% in the same incubation time (72 h) (Fig. 4). Since A. castellanii usually feeds on bacteria, OMVs may have served as an additional source of growth factors.

FIG. 4.

OMVs are not enough to kill L. pneumophila host cells. NCI-H292 alveolar epithelial cells (▪) and A. castellanii (A. c.) protozoan host cells (▴) were incubated with 50 μg (total protein) of OMVs. Cell suspensions without OMVs served as controls (□ and ▵). After 24 h Alamar blue was added. Then cell growth was monitored by examining Alamar blue reduction over 72 h at 24-h intervals.

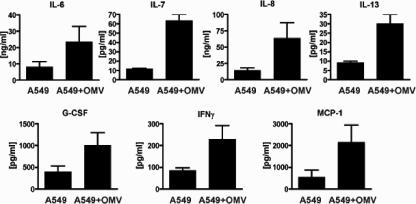

L. pneumophila OMVs induce a specific cytokine profile.

Upon L. pneumophila recognition, human host cells exhibit a specific cytokine response (71, 81). To examine how OMVs contribute to this response, we analyzed the cytokine secretion profiles of alveolar epithelial cells upon incubation with OMVs by using the Bioplex protein array system. After 15 h of incubation with OMVs, the cytokines IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, IL-13, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, IFN-γ, and monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 were induced (Fig. 5), but IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, IL-12, IL-17, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, and tumor necrosis factor alpha were not induced (data not shown). Compared with cytokine secretion profiles induced by L. pneumophila cells (71), OMVs specifically stimulated IL-7 and IL-13 secretion. Additional treatment of OMV samples with protease inhibitors (phosphoramidon and complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail) and heat inactivation did not change the profile (data not shown). This suggests that OMV components other than proteins are responsible for the cytokine stimulation.

FIG. 5.

OMV fraction of L. pneumophila stimulates cytokine secretion. A549 alveolar epithelial cells were stimulated for 15 h with 50 μg (total protein) of OMVs, and then cytokine secretion profiles were determined using the Bioplex system. The graphs show induced cytokines. The data are means and standard deviations of at least three independent experiments. Main effects were then compared using the Newman-Keuls posttest. A P value of <0.01 was considered significant. G-CSF, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor; MCP-1, monocyte chemoattractant protein 1.

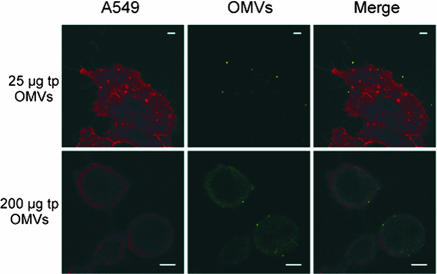

OMVs bind to the cytoplasmic membrane of alveolar epithelial cells.

OMVs are vehicles by which virulence factors, membrane compounds, including LPS, and periplasmic cargo can be transported to host cells or tissues during extracellular attack (48). On the other hand, they can be translocated to the host phagosome membrane during intracellular growth (29). However, the fate of OMVs and the mode of effector molecule delivery to the host remain to be established. The possible extracellular interactions include the binding of OMVs to host cells, fusion of OMVs with host cytoplasmic membranes, and the incorporation of OMVs by phagocytosis. To characterize the membrane interaction, A549 cells were incubated with purified OMVs (25 and 200 μg of total vesicle protein per 2 × 104 A549 cells) and washed with PBS. The OMV interaction with host cells was analyzed by using LPS antibody staining (green) and WGA-Alexa Fluor host membrane labeling (red). Analysis by confocal microscopy revealed acquisition of green fluorescence on the surface of alveolar epithelial cells (Fig. 6), which suggests either that OMVs persist on the surface or that they fuse with the cytoplasmic membrane of the target cell. The acquisition of fluorescence was dependent upon the presence of OMVs, as cells which were not exposed to OMVs exhibited no detectable green fluorescence. Moreover, as shown in Fig. 6, the morphology of the host cells changed toward a round shape upon OMV exposure. This phenomenon became more prominent when increasing amounts of OMVs (0, 25, and 200 μg of total protein) were added.

FIG. 6.

Binding of L. pneumophila OMVs to host cell membranes. A549 alveolar epithelial cells (red) were incubated for 8 h with 25 μg (total protein) and 200 μg (total protein) of OMVs (green). OMVs were stained with mouse anti-LPS monoclonal antibodies, which were subsequently visualized by using Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G. Host cell membranes were labeled by using WGA-Alexa Fluor 594. Bars = 5 μm.

DISCUSSION

Secreted effector molecules are critical for the extracellular pathogenicity of L. pneumophila, which is characterized by considerable tissue destruction, including extracellular matrix degradation and focal septal disruption (78). On the other hand, it is well known that specific secretion machineries, like the Dot/Icm type IV system and OMVs, contribute to the intracellular pathogenicity of L. pneumophila, which is characterized by the inhibition of phagosome maturation, altered host membrane traffic, and intracellular bacterial growth within phagocytes (29, 78).

In this paper we provide microscopic evidence that OMVs are indeed produced intracellularly within Legionella-specific phagosomes. This result is consistent with the hypothesis that pathogenic legionellae utilize OMVs to disseminate effector molecules into phagosomes to inhibit phagolysosome fusion (29). We also observed that OMVs form during extracellular growth, indicating that OMVs influence other environments as well. Moreover, by using medium-grown L. pneumophila cultures it could be shown that OMV production also occurred during stationary growth phase. This is relevant since L. pneumophila differentiates into the transmissive form during the postexponential phase. Consequently, we used bacterial cultures from early stationary phase to purify SSP and OMV subfractions for further analysis.

Proteome analysis of OMVs and SSPs.

So far, extracellular proteomes of various gram-positive and gram-negative bacterial pathogens have been characterized (17, 60, 84). A proteomic analysis of type II secreted effector proteins of L. pneumophila was recently described (26). The only proteomic studies of OMVs are the Neisseria meningitidis studies (30, 80), which formed the basis for the development of MeNZB, an OMV vaccine against serogroup B (61).

Our proteomic analysis of L. pneumophila culture supernatants revealed 493 protein spots, which resulted in 181 identified distinct proteins. Many identified proteins produced more than one spot or even multiple spots, which might have been due to artificial (deamidation) or posttranslational modifications or to degradation by supernatant proteases (13). The resolved protein composition of each fraction was found to be highly specific. The SSP and OMV fractions contained 107 and 33 specific proteins, respectively, whereas only 41 proteins appeared in both fractions. The identified type II secretion substrates of both fractions included several degradative enzymes, including an acid phosphatase (Map) (lpg1119), a protease (ProA1/Msp), a chitinase (ChiA) (lpg1116), an RNase (lpg2848), and a lysophospholipase (lpg2343) (26). Some of these enzymes are known to promote the virulence of L. pneumophila. Although not essential for infection, the metalloprotease ProA1, which was one of the most abundant proteins in the supernatant, exhibits hemolytic and cytotoxic activities in vitro and contributes to tissue damage in vivo (15, 55, 62). Likewise, the recently discovered novel virulence factor chitinase ChiA promotes L. pneumophila persistence in the lung (26). The detection of 38 putative type II substrates in our supernatant subfraction so far supports the hypothesis of DebRoy and colleagues that the type II secretion system can process 60 or more proteins. However, for type IV secretion, only three substrates, LaiE (lpg2154), LaiF (SdeD) (lpg2509), and WipC (lpg2206), were found. This defective secretion might be explained by the lack of host cell contact (20). Especially interesting is the fact that seven eukaryote-like proteins were present in the subfractions (Table 1). Although the exact functions of these proteins are still unclear, their contributions to L. pneumophila pathogenesis have been postulated (16, 18). By mimicking functions of their eukaryotic relatives (e.g., in signaling or in degradative processes), these proteins may allow Legionella to communicate with eukaryotic cells and thus contribute to survival and replication.

Another interesting aspect is the distribution of L. pneumophila virulence factors. Of 25 identified L. pneumophila virulence factors, 18 were associated with OMVs. Eight of these factors, including Mip, one of the main virulence factors of L. pneumophila, were unique to OMVs. This observation confirms that OMVs are specific carriers for some virulence-associated effectors. Thus, it is very interesting to analyze OMVs with regard to their putative function as bacterial “missiles” or “communication satellites.”

Degradative enzymatic activities.

The administration of culture filtrate components of L. pneumophila to the lungs of guinea pigs elicited lesions which were pathologically similar to those seen in animals with clinical and experimentally induced Legionnaires' disease (11, 23). These previous studies, as well as more recent studies, suggest that various enzymatic activities may be responsible for this phenomenon (34, 78).

The zymography and enzyme assays performed in our study revealed that the SSP and OMV fractions possess proteolytic and lipolytic enzyme activities which may contribute to the destruction of the alveolar lining during infection. The observed proteolytic effects could be due to several identified proteins, like the metalloprotease ProA1, the eukaryote-like astacin protease LegP (lpg2999), the elastase LasB (lpg1655), and a serine metalloprotease (lpg2019). As ProA1 is one of the most abundant proteins in the supernatant, it is likely that this protease is largely responsible for the tissue damage mentioned above. Furthermore, as proposed recently, the identified secreted serine metalloprotease (lpg2019) might enable L. pneumophila, in synergism with OMV-associated Mip, to transmigrate through a barrier of NCI-H292 lung epithelial cells and extracellular matrix (78). The destruction of the extracellular matrix protein elastin could be due to secreted LasB. Analogous to findings for P. aeruginosa, the elastase may additionally degrade surfactant proteins A and D (52). Moreover, activities associated with Legionella SSPs and OMVs evidently broke down two synthetic lipid substrates, NPP and NPPC. Here, our proteome data suggest several lipases which could be responsible for this finding, including a PlcB homolog (lpg1455), a PlaC homolog (lpg2837), a PlcA homolog (lpg0502), and a PlaA homolog (lpg2343). Again, the OMV-specific Mip might be involved in the destruction processes, as it was also shown to promote an extracellular phospholipase C-like activity (25). The observed destruction of bovine surfactant by L. pneumophila phospholipase A (32) and our results suggest that SSPs and OMVs may degrade human surfactant lipids and thus contribute to bacterial transmigration through the lung epithelium barrier. The protein sorting of virulence factors into OMVs, the small size of OMVs, which allows interaction with tissue structures not readily accessible to larger bacteria, and the possibility that some membrane-associated toxins are more active than the toxin alone additionally support the view that OMVs may pave the way for Legionella infection (48).

Cellular effects.

Considering the different destructive enzyme activities, we also analyzed the cytopathic effects of OMVs on human alveolar epithelial cells and the protozoan host A. castellanii. However, unlike OMVs of other species (9, 47, 79), L. pneumophila OMVs were not cytotoxic or cytolytic. In agreement with the previous observation that L. pneumophila-free culture supernatants do not induce apoptosis (35), we did not observe OMV-mediated apoptosis. Surprisingly, the growth of A. castellanii was increased by coincubation with OMVs. Since A. castellanii utilizes peptides and amino acids, it may be speculated that OMVs serve as a source of food particles, which attracts host protozoans to L. pneumophila in the environment. OMVs contain various compounds (LPS, lipoproteins, and proteins) that are recognized by eukaryotic cells and modulate the release of cytokines. Indeed, our cytokine profiling experiments revealed that OMVs induce a specific cytokine secretion profile in alveolar epithelial cells, including (for example) the proinflammatory cytokines IL-6, IL-8, and IFN-γ, as well as the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-13. Compared to L. pneumophila cells (71), OMVs specifically stimulated the release of IL-7 and IL-13. This might be explained by the finding that L. pneumophila alters the composition of secreted LPS (associated with OMVs) but not the composition of LPS on the cell surface in the transmissive phase (29; F. Galka, unpublished data). Taken together, these data indicate that there is modulation of the host cell response (13, 81).

Binding of OMVs to alveolar epithelial cells.

L. pneumophila expresses a number of surface factors which are known to mediate adherence to host cells (37, 74). The finding that OMVs, which present a subset of outer membrane proteins, bind to alveolar epithelial cells is consistent with this observation. Based on the protein composition of L. pneumohila OMVs, it is likely that, for example, Hsp60, a molecular chaperone which was previously shown to contribute to adherence of L. pneumophila to HeLa cells, contributes to the observed process (36, 37). Thus, the mode of OMV binding seems to reflect at least partially that of Legionella cells.

Recently, it was proposed that L. pneumophila releases OMVs into the phagosome, which intercalates into the phagosomal membrane and thereby inhibits the fusion with lysosomes (29). Our observation that extracellular exposure to OMVs triggers significant morphological changes in host cells suggests additional modulatory and pathogenic effects of Legionella OMVs. In this regard it will be interesting to analyze how the identified eukaryote-like proteins, virulence factors like the SidE paralogs LaiE and LaiF, and the hypothetical proteins with unknown functions reach their target structures and subvert, mimic, or usurp host cell functions.

Conclusion.

In summary, our proteomic analysis allowed for the first time exact allocation of L. pneumophila virulence factors to extracellular SSP and OMV fractions. The findings demonstrate that the two fractions are partially independent of each other with respect to composition but probably contribute synergistically to infection. Zymography and enzyme assays revealed that SSPs and OMVs possess proteolytic and lipolytic enzyme activities. Furthermore, OMVs activate a specific cytokine response. Thus, these results highlight the potential impact of vesicle-mediated secretion on host modulation. Additionally, an ability of OMVs to deliver enzymes (e.g., Mip or proteases) may also be relevant for extracellular targets like the extracellular matrix of the lung epithelium barrier or biofilms in the environment. Hence, OMVs may promote the dissemination of L. pneumophila by degrading local matrices and facilitating bacterial transmigration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Melanie Glaser and Kerstin Möhr for excellent technical assistance, Christoph Batzilla for our introduction to 2-DE, and Alicia Ponte-Sucre, Klaus Heuner, and Heike Bruhn for helpful discussions. We are grateful to Monica Persson and to Carina Wagner, Markus Wehrl, Georg Krohne, and Franziska Agerer for kind help with microscopic techniques.

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG Sonderforschungsbereich 630-B1) and BMBF (grant CAPNETZ C15). Work at Umea University was supported by the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Foundation for International Cooperation in Research and Higher Education (STINT), and the Faculty of Medicine, and it was performed at the Umea Centre for Microbial Research.

Editor: A. Camilli

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 4 February 2008.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://iai.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agerer, F., S. Lux, A. Michel, M. Rohde, K. Ohlsen, and C. R. Hauck. 2005. Cellular invasion by Staphylococcus aureus reveals a functional link between focal adhesion kinase and cortactin in integrin-mediated internalisation. J. Cell Sci. 1182189-2200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agerer, F., S. Waeckerle, and C. R. Hauck. 2004. Microscopic quantification of bacterial invasion by a novel antibody-independent staining method. J. Microbiol. Methods 5923-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahmed, S. A., R. M. Gogal, Jr., and J. E. Walsh. 1994. A new rapid and simple non-radioactive assay to monitor and determine the proliferation of lymphocytes: an alternative to [3H]thymidine incorporation assay. J. Immunol. Methods 170211-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Albert-Weissenberger, C., C. Cazalet, and C. Buchrieser. 2007. Legionella pneumophila—a human pathogen that co-evolved with fresh water protozoa. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 64432-448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andrews, H. L., J. P. Vogel, and R. R. Isberg. 1998. Identification of linked Legionella pneumophila genes essential for intracellular growth and evasion of the endocytic pathway. Infect. Immun. 66950-958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aragon, V., S. Kurtz, and N. P. Cianciotto. 2001. Legionella pneumophila major acid phosphatase and its role in intracellular infection. Infect. Immun. 69177-185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aragon, V., S. Kurtz, A. Flieger, B. Neumeister, and N. P. Cianciotto. 2000. Secreted enzymatic activities of wild-type and pilD-deficient Legionella pneumophila. Infect. Immun. 681855-1863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aragon, V., O. Rossier, and N. P. Cianciotto. 2002. Legionella pneumophila genes that encode lipase and phospholipase C activities. Microbiology 1482223-2231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Balsalobre, C., J. M. Silvan, S. Berglund, Y. Mizunoe, B. E. Uhlin, and S. N. Wai. 2006. Release of the type I secreted alpha-haemolysin via outer membrane vesicles from Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 5999-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Banerji, S., M. Bewersdorff, B. Hermes, N. P. Cianciotto, and A. Flieger. 2005. Characterization of the major secreted zinc metalloprotease-dependent glycerophospholipid:cholesterol acyltransferase, PlaC, of Legionella pneumophila. Infect. Immun. 732899-2909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baskerville, A., J. W. Conlan, L. A. Ashworth, and A. B. Dowsett. 1986. Pulmonary damage caused by a protease from Legionella pneumophila. Br. J. Exp. Pathol. 67527-536. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Batzilla, C. F., S. Rachid, S. Engelmann, M. Hecker, J. Hacker, and W. Ziebuhr. 2006. Impact of the accessory gene regulatory system (Agr) on extracellular proteins, codY expression and amino acid metabolism in Staphylococcus epidermidis. Proteomics 63602-3613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bauman, S. J., and M. J. Kuehn. 2006. Purification of outer membrane vesicles from Pseudomonas aeruginosa and their activation of an IL-8 response. Microbes Infect. 82400-2408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beveridge, T. J. 1999. Structures of gram-negative cell walls and their derived membrane vesicles. J. Bacteriol. 1814725-4733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blander, S. J., L. Szeto, H. A. Shuman, and M. A. Horwitz. 1990. An immunoprotective molecule, the major secretory protein of Legionella pneumophila, is not a virulence factor in a guinea pig model of Legionnaires' disease. J. Clin. Investig. 86817-824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brüggemann, H., C. Cazalet, and C. Buchrieser. 2006. Adaptation of Legionella pneumophila to the host environment: role of protein secretion, effectors and eukaryotic-like proteins. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 986-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bumann, D., S. Aksu, M. Wendland, K. Janek, U. Zimny-Arndt, N. Sabarth, T. F. Meyer, and P. R. Jungblut. 2002. Proteome analysis of secreted proteins of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Infect. Immun. 703396-3403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cazalet, C., C. Rusniok, H. Brüggemann, N. Zidane, A. Magnier, L. Ma, M. Tichit, S. Jarraud, C. Bouchier, F. Vandenesch, F. Kunst, J. Etienne, P. Glaser, and C. Buchrieser. 2004. Evidence in the Legionella pneumophila genome for exploitation of host cell functions and high genome plasticity. Nat. Genet. 361165-1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen, J., K. S. de Felipe, M. Clarke, H. Lu, O. R. Anderson, G. Segal, and H. A. Shuman. 2004. Legionella effectors that promote nonlytic release from protozoa. Science 3031358-1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen, J., M. Reyes, M. Clarke, and H. A. Shuman. 2007. Host cell-dependent secretion and translocation of the LepA and LepB effectors of Legionella pneumophila. Cell. Microbiol. 91660-1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chien, M., I. Morozova, S. Shi, H. Sheng, J. Chen, S. M. Gomez, G. Asamani, K. Hill, J. Nuara, M. Feder, J. Rineer, J. J. Greenberg, V. Steshenko, S. H. Park, B. Zhao, E. Teplitskaya, J. R. Edwards, S. Pampou, A. Georghiou, I. C. Chou, W. Iannuccilli, M. E. Ulz, D. H. Kim, A. Geringer-Sameth, C. Goldsberry, P. Morozov, S. G. Fischer, G. Segal, X. Qu, A. Rzhetsky, P. Zhang, E. Cayanis, P. J. De Jong, J. Ju, S. Kalachikov, H. A. Shuman, and J. J. Russo. 2004. The genomic sequence of the accidental pathogen Legionella pneumophila. Science 3051966-1968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cianciotto, N. P. 2005. Type II secretion: a protein secretion system for all seasons. Trends Microbiol. 13581-588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Conlan, J. W., A. Baskerville, and L. A. Ashworth. 1986. Separation of Legionella pneumophila proteases and purification of a protease which produces lesions like those of Legionnaires' disease in guinea pig lung. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1321565-1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Conover, G. M., I. Derre, J. P. Vogel, and R. R. Isberg. 2003. The Legionella pneumophila LidA protein: a translocated substrate of the Dot/Icm system associated with maintenance of bacterial integrity. Mol. Microbiol. 48305-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DebRoy, S., V. Aragon, S. Kurtz, and N. P. Cianciotto. 2006. Legionella pneumophila Mip, a surface-exposed peptidylproline cis-trans-isomerase, promotes the presence of phospholipase C-like activity in culture supernatants. Infect. Immun. 745152-5160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DebRoy, S., J. Dao, M. Soderberg, O. Rossier, and N. P. Cianciotto. 2006. Legionella pneumophila type II secretome reveals unique exoproteins and a chitinase that promotes bacterial persistence in the lung. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10319146-19151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eymann, C., A. Dreisbach, D. Albrecht, J. Bernhardt, D. Becher, S. Gentner, T. Tam le, K. Buttner, G. Buurman, C. Scharf, S. Venz, U. Volker, and M. Hecker. 2004. A comprehensive proteome map of growing Bacillus subtilis cells. Proteomics 42849-2876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Feeley, J. C., R. J. Gibson, G. W. Gorman, N. C. Langford, J. K. Rasheed, D. C. Mackel, and W. B. Baine. 1979. Charcoal-yeast extract agar: primary isolation medium for Legionella pneumophila. J. Clin. Microbiol. 10437-441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fernandez-Moreira, E., J. H. Helbig, and M. S. Swanson. 2006. Membrane vesicles shed by Legionella pneumophila inhibit fusion of phagosomes with lysosomes. Infect. Immun. 743285-3295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ferrari, G., I. Garaguso, J. Adu-Bobie, F. Doro, A. R. Taddei, A. Biolchi, B. Brunelli, M. M. Giuliani, M. Pizza, N. Norais, and G. Grandi. 2006. Outer membrane vesicles from group B Neisseria meningitidis delta gna33 mutant: proteomic and immunological comparison with detergent-derived outer membrane vesicles. Proteomics 61856-1866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Flesher, A. R., S. Ito, B. J. Mansheim, and D. L. Kasper. 1979. The cell envelope of the Legionnaires' disease bacterium. Morphologic and biochemical characteristics. Ann. Intern. Med. 90628-630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Flieger, A., S. Gongab, M. Faigle, H. A. Mayer, U. Kehrer, J. Mussotter, P. Bartmann, and B. Neumeister. 2000. Phospholipase A secreted by Legionella pneumophila destroys alveolar surfactant phospholipids. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 188129-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Flieger, A., B. Neumeister, and N. P. Cianciotto. 2002. Characterization of the gene encoding the major secreted lysophospholipase A of Legionella pneumophila and its role in detoxification of lysophosphatidylcholine. Infect. Immun. 706094-6106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Flieger, A., K. Rydzewski, S. Banerji, M. Broich, and K. Heuner. 2004. Cloning and characterization of the gene encoding the major cell-associated phospholipase A of Legionella pneumophila, plaB, exhibiting hemolytic activity. Infect. Immun. 722648-2658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gao, L. Y., and Y. Abu Kwaik. 1999. Activation of caspase 3 during Legionella pneumophila-induced apoptosis. Infect. Immun. 674886-4894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Garduno, R. A., G. Faulkner, M. A. Trevors, N. Vats, and P. S. Hoffman. 1998. Immunolocalization of Hsp60 in Legionella pneumophila. J. Bacteriol. 180505-513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Garduno, R. A., E. Garduno, and P. S. Hoffman. 1998. Surface-associated Hsp60 chaperonin of Legionella pneumophila mediates invasion in a HeLa cell model. Infect. Immun. 664602-4610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gardy, J. L., M. R. Laird, F. Chen, S. Rey, C. J. Walsh, M. Ester, and F. S. Brinkman. 2005. PSORTb v. 2.0: expanded prediction of bacterial protein subcellular localization and insights gained from comparative proteome analysis. Bioinformatics 21617-623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hägele, S., R. Kohler, H. Merkert, M. Schleicher, J. Hacker, and M. Steinert. 2000. Dictyostelium discoideum: a new host model system for intracellular pathogens of the genus Legionella. Cell. Microbiol. 2165-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hales, L. M., and H. A. Shuman. 1999. Legionella pneumophila contains a type II general secretion pathway required for growth in amoebae as well as for secretion of the Msp protease. Infect. Immun. 673662-3666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heussen, C., and E. B. Dowdle. 1980. Electrophoretic analysis of plasminogen activators in polyacrylamide gels containing sodium dodecyl sulfate and copolymerized substrates. Anal. Biochem. 102196-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Howe, T. R., and B. H. Iglewski. 1984. Isolation and characterization of alkaline protease-deficient mutants of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in vitro and in a mouse eye model. Infect. Immun. 431058-1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kanehisa, M., S. Goto, M. Hattori, K. F. Aoki-Kinoshita, M. Itoh, S. Kawashima, T. Katayama, M. Araki, and M. Hirakawa. 2006. From genomics to chemical genomics: new developments in KEGG. Nucleic Acids Res. 34D354-D357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kessler, E., M. Israel, N. Landshman, A. Chechick, and S. Blumberg. 1982. In vitro inhibition of Pseudomonas aeruginosa elastase by metal-chelating peptide derivatives. Infect. Immun. 38716-723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kesty, N. C., K. M. Mason, M. Reedy, S. E. Miller, and M. J. Kuehn. 2004. Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli vesicles target toxin delivery into mammalian cells. EMBO J. 234538-4549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kohler, R., J. Fanghanel, B. Konig, E. Luneberg, M. Frosch, J. U. Rahfeld, R. Hilgenfeld, G. Fischer, J. Hacker, and M. Steinert. 2003. Biochemical and functional analyses of the Mip protein: influence of the N-terminal half and of peptidylprolyl isomerase activity on the virulence of Legionella pneumophila. Infect. Immun. 714389-4397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kouokam, J. C., S. N. Wai, M. Fallman, U. Dobrindt, J. Hacker, and B. E. Uhlin. 2006. Active cytotoxic necrotizing factor 1 associated with outer membrane vesicles from uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 742022-2030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kuehn, M. J., and N. C. Kesty. 2005. Bacterial outer membrane vesicles and the host-pathogen interaction. Genes Dev. 192645-2655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lu, Z., D. Szafron, R. Greiner, P. Lu, D. S. Wishart, B. Poulin, J. Anvik, C. Macdonell, and R. Eisner. 2004. Predicting subcellular localization of proteins using machine-learned classifiers. Bioinformatics 20547-556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Luo, Z. Q., and R. R. Isberg. 2004. Multiple substrates of the Legionella pneumophila Dot/Icm system identified by interbacterial protein transfer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101841-846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Machner, M. P., and R. R. Isberg. 2006. Targeting of host Rab GTPase function by the intravacuolar pathogen Legionella pneumophila. Dev. Cell 1147-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mariencheck, W. I., J. F. Alcorn, S. M. Palmer, and J. R. Wright. 2003. Pseudomonas aeruginosa elastase degrades surfactant proteins A and D. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 28528-537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Matthews, M., and C. R. Roy. 2000. Identification and subcellular localization of the Legionella pneumophila IcmX protein: a factor essential for establishment of a replicative organelle in eukaryotic host cells. Infect. Immun. 683971-3982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McBride, J., P. R. Ingram, F. L. Henriquez, and C. W. Roberts. 2005. Development of colorimetric microtiter plate assay for assessment of antimicrobials against Acanthamoeba. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43629-634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moffat, J. F., P. H. Edelstein, D. P. Regula, Jr., J. D. Cirillo, and L. S. Tompkins. 1994. Effects of an isogenic Zn-metalloprotease-deficient mutant of Legionella pneumophila in a guinea-pig pneumonia model. Mol. Microbiol. 12693-705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Murata, T., A. Delprato, A. Ingmundson, D. K. Toomre, D. G. Lambright, and C. R. Roy. 2006. The Legionella pneumophila effector protein DrrA is a Rab1 guanine nucleotide-exchange factor. Nat. Cell Biol. 8971-977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nagai, H., J. C. Kagan, X. Zhu, R. A. Kahn, and C. R. Roy. 2002. A bacterial guanine nucleotide exchange factor activates ARF on Legionella phagosomes. Science 295679-682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nagai, H., and C. R. Roy. 2003. Show me the substrates: modulation of host cell function by type IV secretion systems. Cell. Microbiol. 5373-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ninio, S., and C. R. Roy. 2007. Effector proteins translocated by Legionella pneumophila: strength in numbers. Trends Microbiol. 15372-380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nouwens, A. S., M. D. Willcox, B. J. Walsh, and S. J. Cordwell. 2002. Proteomic comparison of membrane and extracellular proteins from invasive (PAO1) and cytotoxic (6206) strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proteomics 21325-1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Oster, P., D. Lennon, J. O'Hallahan, K. Mulholland, S. Reid, and D. Martin. 2005. MeNZB: a safe and highly immunogenic tailor-made vaccine against the New Zealand Neisseria meningitidis serogroup B disease epidemic strain. Vaccine 232191-2196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Quinn, F. D., and L. S. Tompkins. 1989. Analysis of a cloned sequence of Legionella pneumophila encoding a 38 kD metalloprotease possessing haemolytic and cytotoxic activities. Mol. Microbiol. 3797-805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rey, S., M. Acab, J. L. Gardy, M. R. Laird, K. deFays, C. Lambert, and F. S. Brinkman. 2005. PSORTdb: a protein subcellular localization database for bacteria. Nucleic Acids Res. 33D164-D168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rodgers, F. G. 1979. Ultrastructure of Legionella pneumophila. J. Clin. Pathol. 321195-1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rossier, O., and N. P. Cianciotto. 2001. Type II protein secretion is a subset of the PilD-dependent processes that facilitate intracellular infection by Legionella pneumophila. Infect. Immun. 692092-2098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rossier, O., S. R. Starkenburg, and N. P. Cianciotto. 2004. Legionella pneumophila type II protein secretion promotes virulence in the A/J mouse model of Legionnaires' disease pneumonia. Infect. Immun. 72310-321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sadosky, A. B., L. A. Wiater, and H. A. Shuman. 1993. Identification of Legionella pneumophila genes required for growth within and killing of human macrophages. Infect. Immun. 615361-5373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Samrakandi, M. M., S. L. Cirillo, D. A. Ridenour, L. E. Bermudez, and J. D. Cirillo. 2002. Genetic and phenotypic differences between Legionella pneumophila strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 401352-1362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sansom, F. M., H. J. Newton, S. Crikis, N. P. Cianciotto, P. J. Cowan, A. J. d'Apice, and E. L. Hartland. 2007. A bacterial ecto-triphosphate diphosphohydrolase similar to human CD39 is essential for intracellular multiplication of Legionella pneumophila. Cell. Microbiol. 91922-1935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sansom, F. M., H. J. Newton, and E. L. Hartland. 2006. Eukaryotic-like proteins of Legionella pneumophila as potential virulence factors, p. 246-250. In N. P. Cianciotto, Y. Abu Kwaik, P. H. Edelstein, B. S. Fields, D. F. Geary, T. G. Harrison, C. A. Joseph, R. M. Ratcliff, J. E. Stout, and M. S. Swanson (ed.), Legionella: state of the art 30 years after its recognition. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 71.Schmeck, B., P. D. N′Guessan, M. Ollomang, J. Lorenz, J. Zahlten, B. Opitz, A. Flieger, N. Suttorp, and S. Hippenstiel. 2007. Legionella pneumophila-induced NF-κB- and MAPK-dependent cytokine release by lung epithelial cells. Eur. Respir. J. 2925-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Segal, G., and H. A. Shuman. 1999. Legionella pneumophila utilizes the same genes to multiply within Acanthamoeba castellanii and human macrophages. Infect. Immun. 672117-2124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shuman, H. A., C. D. Pericone, N. Shohdy, K. S. de Felipe, and M. Clarke. 2006. Function of Legionella effectors, p. 177-183. In N. P. Cianciotto, Y. Abu Kwaik, P. H. Edelstein, B. S. Fields, D. F. Geary, T. G. Harrison, C. A. Joseph, R. M. Ratcliff, J. E. Stout, and M. S. Swanson (ed.), Legionella: state of the art 30 years after its recognition. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 74.Steinert, M., U. Hentschel, and J. Hacker. 2002. Legionella pneumophila: an aquatic microbe goes astray. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 26149-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Swanson, M. S., and B. K. Hammer. 2000. Legionella pneumophila pathogenesis: a fateful journey from amoebae to macrophages. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 54567-613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tullius, M. V., G. Harth, and M. A. Horwitz. 2001. High extracellular levels of Mycobacterium tuberculosis glutamine synthetase and superoxide dismutase in actively growing cultures are due to high expression and extracellular stability rather than to a protein-specific export mechanism. Infect. Immun. 696348-6363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Vincent, C. D., J. R. Friedman, K. C. Jeong, E. C. Buford, J. L. Miller, and J. P. Vogel. 2006. Identification of the core transmembrane complex of the Legionella Dot/Icm type IV secretion system. Mol. Microbiol. 621278-1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wagner, C., A. S. Khan, T. Kamphausen, B. Schmausser, C. Unal, U. Lorenz, G. Fischer, J. Hacker, and M. Steinert. 2007. Collagen binding protein Mip enables Legionella pneumophila to transmigrate through a barrier of NCI-H292 lung epithelial cells and extracellular matrix. Cell. Microbiol. 9450-462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wai, S. N., B. Lindmark, T. Soderblom, A. Takade, M. Westermark, J. Oscarsson, J. Jass, A. Richter-Dahlfors, Y. Mizunoe, and B. E. Uhlin. 2003. Vesicle-mediated export and assembly of pore-forming oligomers of the enterobacterial ClyA cytotoxin. Cell 11525-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Williams, J. N., P. J. Skipp, H. E. Humphries, M. Christodoulides, C. D. O'Connor, and J. E. Heckels. 2007. Proteomic analysis of outer membranes and vesicles from wild-type serogroup B Neisseria meningitidis and a lipopolysaccharide-deficient mutant. Infect. Immun. 751364-1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wilson, M., R. Seymour, and B. Henderson. 1998. Bacterial perturbation of cytokine networks. Infect. Immun. 662401-2409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Winn, W. C., Jr. 1988. Legionnaires disease: historical perspective. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 160-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Winn, W. C., Jr., and R. L. Myerowitz. 1981. The pathology of the Legionella pneumonias. A review of 74 cases and the literature. Hum. Pathol. 12401-422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yu, H. B., R. Kaur, S. Lim, X. H. Wang, and K. Y. Leung. 2007. Characterization of extracellular proteins produced by Aeromonas hydrophila AH-1. Proteomics 7436-449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.