Abstract

Biofilm formation in Staphylococcus aureus under in vitro growth conditions is generally promoted by high concentrations of sugar and/or salts. The addition of glucose to routinely used complex growth media triggered biofilm formation in S. aureus strain SA113. Deletion of ccpA, coding for the catabolite control protein A (CcpA), which regulates gene expression in response to the carbon source, abolished the capacity of SA113 to form a biofilm under static and flow conditions, while still allowing primary attachment to polystyrene surfaces. This suggested that CcpA mainly affects biofilm accumulation and intercellular aggregation. trans-Complementation of the mutant with the wild-type ccpA allele fully restored the biofilm formation. The biofilm produced by SA113 was susceptible to sodium metaperiodate, DNase I, and proteinase K treatment, indicating the presence of polysaccharide intercellular adhesin (PIA), protein factors, and extracellular DNA (eDNA). The investigation of several factors which were reported to influence biofilm formation in S. aureus (arlRS, mgrA, rbf, sarA, atl, ica, citZ, citB, and cidABC) showed that CcpA up-regulated the transcription of cidA, which was recently shown to contribute to eDNA production. Moreover, we showed that CcpA increased icaA expression and PIA production, presumably over the down-regulation of the tricarboxylic acid cycle genes citB and citZ.

Staphylococcus epidermidis and Staphylococcus aureus are the most frequent causes of foreign body-associated infections, mainly due to their ability to form an adherent, multilayer bacterial biofilm on all sorts of surfaces. Embedment in a polymeric matrix protects bacteria from host defenses (3), and the altered gene expression of the sessile form (43) renders them refractory to antibiotic treatment.

Biofilm formation is a multistep process, characterized by attachment of the cells to a surface by physicochemical interactions, which is followed by growth-dependent intercellular accumulation, glycocalyx formation, maturation of the biofilm, and finally escape of the bacteria from the biofilm (22). Besides the overall cell charge and hydrophobicity, which can affect initial attachment to various surfaces, staphylococci possess an impressive number of surface-associated adhesins (microbial surface components recognizing adhesive matrix molecules, or MSCRAMMS) to adhere to the host's matrix proteins (20). The genetic and molecular basis of biofilm formation in staphylococci is multifaceted (reviewed in reference 39), and the composition of the polymeric biofilm matrix is complex and varies from strain to strain (9).

An important component of many S. epidermidis biofilms is the polysaccharide intercellular adhesin, PIA, also termed polymeric N-acetylglucosamine (PNAG), which is synthesized by the icaADBC-encoded proteins (34, 35). PIA is also produced by S. aureus (13), and the ica operon appears to be present in virtually all S. aureus strains (17, 29, 46). However, the role and importance of PIA in different clinical settings are not completely understood (46). Biofilm formation can also occur in several PIA-independent ways (2): The teichoic acids, surface-exposed charged polymers, which constitute an important part of the S. aureus cell wall, function in primary adherence (23, 57) and are a component of the biofilm matrix as well (49). Proteinaceous factors also contribute significantly to primary attachment and/or promote biofilm formation. Among them are the bifunctional autolysin Atl, which is involved in cell separation (4, 24); possibly also the related cell wall-associated proteins SasG and Pls (12); the biofilm-associated protein Bap, which is mainly found in bovine S. aureus lineages (31); and the aggregation-associated protein Aap from S. epidermidis, which, upon proteolytic processing, induces a PIA-independent biofilm-positive phenotype (47). Functions in biofilm formation were reported also for α-hemolysin, a secreted toxin, but required for cell-cell interactions and biofilm formation (5), as well as for FmtA (16, 55), a penicillin-binding-like protein that plays a role in methicillin resistance (30). Besides proteins, extracellular DNA (eDNA) seems to be a major structural component in staphylococcal biofilms (26, 42, 44).

The regulation of biofilm formation is complex and is influenced by various regulatory systems. The alternative stress sigma factor σB is important in biofilm formation in S. epidermidis but plays a minor role in S. aureus (29, 56). The staphylococcal accessory regulator SarA, which controls the synthesis of certain virulence factors directly or via the agr system and which itself is partly controlled by σB, is essential for biofilm formation in several S. aureus strains (1). Mutations of the accessory gene regulator (agr) were found to affect biofilm formation in some but not all S. aureus strains analyzed (40). A two-component system which positively controls biofilm formation in S. aureus is WalK/WalR, also known as YycG/YycF (15), which plays an important role in cell wall modeling through activation of several genes involved in cell wall degradation.

Several environmental factors have been reported to affect biofilm formation (reviewed in references 22, 33, and 39). Anaerobiosis stimulates ica transcription in S. aureus (14), and growth of S. aureus during infection of a host results in higher PIA production than under in vitro conditions (37). The relative amounts of extracellular PIA and teichoic acids depend on growth conditions such as the choice of the medium or on agitation (49). Especially the presence of sugars seems to play an important role in the stimulation of this process (18, 29). The impact of glucose in the induction of biofilm formation in S. aureus is also reflected by the fact that most of the biofilm adherence assays used in previous studies included high concentrations of either glucose or sucrose (1, 5, 13, 14, 19, 27, 32, 51, 54). Rbf, a member of the AraC/XylS family, was recently suggested to be involved in the regulation of the multicellular aggregation step of S. aureus biofilm formation in response to glucose or salt (32).

We recently showed the impact of the catabolite control protein A (CcpA) on carbon metabolism, up-regulation of certain virulence determinants, and resistance to cell wall-directed antibiotics (50). Since the activity of CcpA is activated in the presence of glucose or sucrose (27), and since CcpA was shown to affect biofilm formation in Bacillus subtilis and Streptococcus mutans (7, 53, 58), we wondered about its role in biofilm formation in S. aureus.

In this study, we deleted the ccpA gene in strain SA113, a biofilm former known to produce PIA (13). We show that, depending on the growth medium, SA113 was able to form a strong biofilm and that the deletion of ccpA reduced its biofilm formation capacity and PIA production.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

The S. aureus strains, plasmids, and primers used in this study are listed in Tables 1 and 2. All strains generated for this study were confirmed by Southern blot analysis and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis of total genome SmaI digests.

TABLE 1.

S. aureus strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant genotype and phenotypea | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| MST04 | RN4220 ccpA::tet(L); Tcr | 50 |

| SA113 | ATCC 35556; PIA-dependent biofilm producer | 25 |

| KS66 | SA113 ccpA::tet(L); Tcr | This study |

| KS66 compl | KS66(pMST1); Kanr; Tcr | This study |

| KS66 empty | KS66(pAW17); Kanr Tcr | This study |

| SA113 Δica | ATCC 35556 Δica::tet; Tcr; deletion of the icaADBC operon | 13 |

| DSM 20231 | Cowan serotype 3 | 52 |

| KS153 | DSM 20231 ccpA::tet(L); Tcr | This study |

| KS153 compl | KS153(pMST1); Kanr Tcr | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pAW17 | Escherichia coli-S. aureus shuttle plasmid with ori pAMα1 and ori ColE1; Kanr | 48 |

| pMST1 | pAW17 with 1.7-kb PCR fragment covering ccpA and its proposed promoter; Kanr | 50 |

Abbreviations: Tcr, tetracycline resistant; Kanr, kanamycin resistant.

TABLE 2.

Primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequence (5′→3′) | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| arlRSprobe+ | TCGTATCACATACCCAACGC | This study |

| arRSprobe− | GAGTATGATGGACAAGACGG | This study |

| citBprobe+ | CAGAGGTGTACCAGCCG | This study |

| citBprobe− | GGTTGTCCAAGCATTCCAG | This study |

| citZprobe+ | CATCTGACAATGATGATACC | This study |

| citZprobe− | GGAGTATGTTACAGATCACG | This study |

| rbfprobe+ | TGATTTACGTGACGAGCTCG | This study |

| rbfprobe− | GCACTATTACTTAAATCTCG | This study |

| atlprobe+ | CCAAGGAACCATTGATAAGC | This study |

| atlprobe− | TGATACTGCTAAACCTACGC | This study |

| mgrAprobe+ | TCTTGAGATAAAGAAGAAGC | This study |

| mgrAprobe− | GAAGTACAATCTAACATACC | This study |

| cidA1-F | CCCATATGCACAAAGTCCAATTA | 59 |

| cidA1-R | CCCTCGAGTTCATAAGCGTCTACACC | 59 |

| SasarAf | AGGGAGGTTTTAAACATGGC | 9a |

| SasarAr | CTCGACTCAATAATGATTCG | 9a |

| 16S-F | CGGAGTGCTTAATGCGTTAG | This study |

| 16S-R | CAATGGGCGAAAGCCTG | This study |

Biofilm assays.

Biofilm formation under static conditions was monitored as described in reference 32. Briefly, Trypticase soy broth (TSB), brain heart infusion (BHI), or LB medium (Becton Dickinson), supplemented with different amounts of glucose, was inoculated 1:200 with an overnight culture. Two hundred microliters of this suspension was transferred to wells of 96-well Nunc Delta tissue culture plates (Roskilde, Denmark) and incubated for 18 h at 37°C. After incubation, the wells were rinsed with 200 μl phosphate-buffered saline three times, air dried, stained with 0.1% safranin for 30 s, and washed three times with distilled water. The adhering dye was dissolved with 30% acetic acid, and the absorption was measured at 530 nm in a microtiter dish reader (Powerwave XS; BioTek). Analoguous experiments were carried out in Nunc 12-well plates using 1 ml of the corresponding suspensions or solutions for a better visual observation.

Biofilm formation under flow conditions was determined basically as described by Beenken et al. (1) using TSB supplemented with 1% glucose, uncoated three-channel flow cells (total volume, 160 μl), and a flow rate of 0.5 ml min−1 for 24 h.

Growth was monitored in 10-ml glass test tubes containing 2 ml of TSB supplemented with 1% glucose and inoculated 1:200 with preculture. Cells were grown for 18 h at 37°C with shaking (180 rpm).

Biofilm stability against protease, sodium metaperiodate, and DNase I treatment.

Biofilm stability assays were carried out in Nunc 12-well plates as described by Toledo-Arana et al. (54), using the growth conditions described above and TSB supplemented with 1% glucose. After 18 h, the medium was removed and substituted with fresh medium supplemented with either 100 μg/ml protease K or 10 mM of sodium metaperiodate and incubated for 2 h at 37°C. Medium without supplement served as a negative control. To test the impact of DNase I, cells were treated as described by Rice et al. (44). Briefly, cells were grown in TSB supplemented with 1% glucose in the presence of 140 U/ml RNase-free DNase I (Fluka, Switzerland) in test tubes or in Nunc plates for 18 h at 37°C. Addition of DNase I had no effect on the growth rates of cells grown in liquid culture.

Growth on CRA.

Congo red agar (CRA) screening was performed basically as described by Knobloch et al. (29). Cells grown on blood plates were diluted to McFarland standard of 0.5, stamped on plates made of TSB agar supplemented with 1% glucose and 0.08% Congo red, and incubated for 18 h at 37°C. MICs of Congo red were determined by broth microdilution modified according to CLSI guidelines (11) in TSB supplemented with 1% glucose.

PIA determination.

PIA production was monitored by analyzing the cell surface extracts from cultures grown for 2 and 8 h in TSB supplemented with 1% glucose. PIA was extracted as described by Cerca et al. (6). Detection was performed using a rabbit polyclonal anti-PIA antibody (19) after blocking with human immunoglobulin G.

Primary adherence measurements.

Primary adherence was measured by diluting cells in the stationary growth phase in TSB supplemented with 1% glucose to obtain approximately 30 CFU/ml. Two milliliters of the appropriate dilutions was added to Nunc Delta six-well-plates and incubated for 30 min at 37°C. In parallel, cells were plated on blood plates to determine the original number of cells applied to the microtiter plates. The six-well plates were rinsed gently three times with 5 ml of sterile phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4) and covered with 3 ml of molten BHI agar (0.8%). Primary attachment was expressed as a percentage of CFU on the six-well-plates compared to the CFU on blood plates.

Quantification of icaA transcription.

The icaA and gyrB transcripts were quantified by LightCycler reverse transcription-PCR as described earlier (19) using RNA samples obtained from cultures grown for 2 and 8 h in TSB supplemented with 1% glucose at 37°C and 200 rpm.

Northern blot analyses.

For Northern blot analyses, cells were grown in TSB supplemented with 1% glucose and harvested after 2 h of growth, with both both wild type and mutant having reached an optical density at 600 nm of approximately 0.4. Cells were centrifuged for 2 min at 12,000 × g, and cell sediments were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. RNA isolation and Northern blotting were performed as described earlier (36). The primer pairs used to generate digoxigenin-labeled arlRS-, citB-, citZ-, rbf-, cidA-, mgrA-, atl-, and sarA-specific probes by PCR labeling are shown in Table 2. All Northern blot analyses were performed at least twice on independently isolated RNA samples. An internal 0.5-kb fragment of the 16S rRNA genes (nucleotides 2232818 to 2233328 of GenBank accession no. CP000046) was used to probe the 16S rRNA gene as a loading control.

Triton X-100-induced autolysis assays.

Autolysis assays were performed as described by Fournier and Hooper (21). Bacteria were grown in TSB supplemented with 1% glucose for 2 h. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation and resuspended in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5)-0.1% Triton X-100 to obtain an A600 of approximately 1. The cells were then incubated at 30°C with shaking, and changes in A600 and CFU were monitored. Results were normalized to CFU at time zero (CFU0): i.e., % living cells at time t = (CFU at time t/CFU0) × 100.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

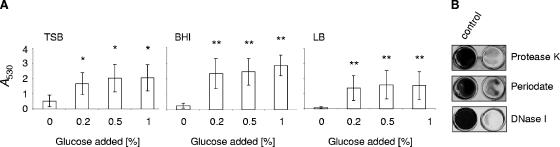

Effect of glucose on biofilm formation in S. aureus SA113. Biofilm formation of strain SA113 in different complex growth media (TSB, BHI, and LB) was shown to be promoted by adding increasing concentrations of glucose. Without glucose supplementation (Fig. 1 A), no significant biofilm formation (A530, <0.5) was observed irrespective of the fact that BHI and TSB already contained substantial amounts of glucose, namely 11 and 14 mM, respectively. Interestingly, supplementation with 0.2% glucose (10 mM) was sufficient to induce a visible biofilm (A530, >1.5) in all three media tested, and a further increase in glucose concentration up to 1% only slightly increased biofilm formation. In contrast to the findings of Beenken et al. (1), who observed biofilm formation of SA113 in polystyrene microtiter plates only in media that were supplemented with both sodium chloride (3%) and glucose and when the wells of the microtiter plates were precoated with plasma proteins, neither addition of 3% salt to the growth medium nor precoating the microtiter plates with plasma proteins was essential for, or increased biofilm formation of SA113 in our experiments, suggesting that SA113 strains with altered adhesion/biofilm-forming capacities may exist in different laboratories.

FIG. 1.

(A) Quantification (A530) of biofilm formation of strain SA113 in different media in response to glucose. Results represent the averages of at least three independent experiments. Error bars indicate the standard deviation of the mean A530. * and **, P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively, for unsupplemented versus supplemented cultures. The media contained the following concentrations of glucose and NaCl before glucose addition: TSB, 0.25% glucose and 0.5% NaCl; BHI, 0.2% glucose and 0.5% NaCl; and LB, 0% glucose and 1% NaCl. (B) Biofilm stability assays of SA113. Preformed biofilms were treated for 2 h with either sodium metaperiodate (10 mM) or proteinase K (100 μg/ml). For the DNase I stability assay, SA113 cells were grown for 18 h in the presence or absence of 140 U/ml DNase I.

Characteristics of the SA113 biofilm.

The biofilm produced by SA113 in TSB supplemented with 1% glucose was sodium metaperiodate, proteinase K, and DNase I sensitive (Fig. 1B), indicating the presence of PIA, proteinaceous factors, and genomic eDNA. This is in line with previous observations (13) and supports the assumption made by Rohde et al. (46) that biofilm formation depends on protein factors in addition to PIA. Moreover, it showed that DNA was also an important structural component of the biofilm formed by this strain.

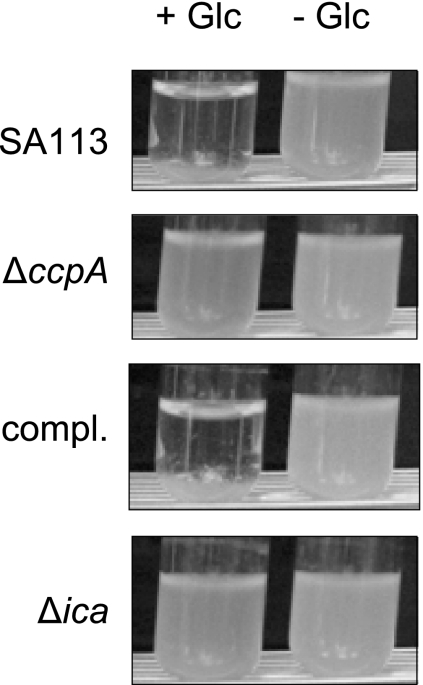

When strain SA113 was grown in glass tubes in TSB supplemented with 1% glucose, cells clumped together and sank to the bottom of the tube, leading to a clearance of the medium (Fig. 2). We analyzed this effect in the ica-negative strain SA113 Δica (13), which remained cloudy after growth in glass tubes in TSB supplemented with 1% glucose (Fig. 2), indicating, that the clumping might be due to PIA production. Interestingly, addition of DNase I (140 U/ml) to the growth medium suppressed the clumping as well (data not shown), suggesting that clumping requires the simultaneous presence of PIA and eDNA.

FIG. 2.

Growth phenotype of SA113, KS66 (ΔccpA), KS66 trans-complemented with plasmid pMST1 (compl.), and SA113 Δica (Δica) grown for 18 h at 37°C in glass tubes in TSB (− Glc) or TSB supplemented with 1% glucose (+ Glc).

Effect of CcpA on biofilm formation.

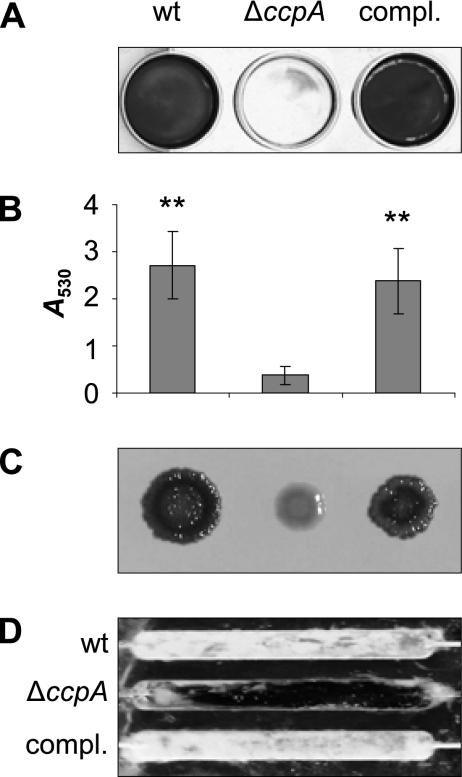

Since glucose supplementation promotes biofilm formation, we analyzed the role of the catabolite control protein A (CcpA) in this process. We deleted ccpA in the biofilm-forming strains SA113 and DSM 20231, yielding strains KS66 and KS157, respectively, and analyzed the capacity of the mutants to form a biofilm. The growth rates of the wild type and ΔccpA mutants were similar. For demonstration of biofilm formation of strain DSM 20231, the plates had to be precoated with 20% human plasma. The deletion of ccpA significantly reduced the biofilm formation capacity of the mutants under the respective static conditions (Fig. 3A [only SA113 shown]), and complementation of the ΔccpA mutants in trans, using pMST1, which contains the wild-type ccpA allele, restored the biofilm formation capacities of both mutants to wild-type levels (Fig. 3A [only SA113 shown]). Transformation of the mutants with the empty control vector had no effect (data not shown), signaling that the decrease in biofilm formation observed in the ΔccpA mutants was due to the deletion of ccpA. Biofilm formation for SA113 was further analyzed by quantifying biofilm formation under static conditions and by observing biofilm formation under flow cell conditions (Fig. 3B and D). Both experiments confirmed the reduced capacity of the mutant to form biofilm. Inactivation of ccpA had no apparent effect on the primary attachment of the mutant to polystyrene surfaces. Both the wild type and mutant showed approximately 10% primary adherence (data not shown). Interestingly, the lack of ccpA in SA113 did suppress the clumping phenotype in the presence of glucose observed for the parental strain grown in glass tubes (Fig. 2). The ΔccpA mutant also lost the ability of its parent to form black and crusty-appearing colonies on CRA plates (Fig. 3C) and formed smaller colonies on CRA. The reason for the latter phenomenon might be the slightly higher susceptibility of the mutant (MIC of 1 g/liter versus 2 g/liter for Congo red), which was in the range of the Congo red concentration in the agar (0.8 g/liter). The crustiness and black color on CRA have been associated with PIA production (29) and might therefore indicate that the ΔccpA mutant of strain SA113 produced less PIA than the wild type. trans-Complementation of KS66 with pMST1 restored both the colony morphology on CRA plates and the clumping phenotype of SA113 cultures grown in glass tubes, indicating that CcpA was involved in the development of both phenotypes.

FIG. 3.

(A) Effect of the ccpA deletion on biofilm formation capacity of S. aureus strain SA113 in TSB supplemented with 1% glucose. wt, wild type. (B) Quantification (A530) of biofilm formation of SA113. Results represent the averages of at least three independent experiments. Error bars indicate the standard deviation of the mean. **, P < 0.01 for wild type and KS66 trans-complemented with plasmid pMST1 (compl.) versus ΔccpA. (C) Growth morphologies of strain SA113 on CRA plates. (D) Biofilm formation of strain SA113 under flow conditions.

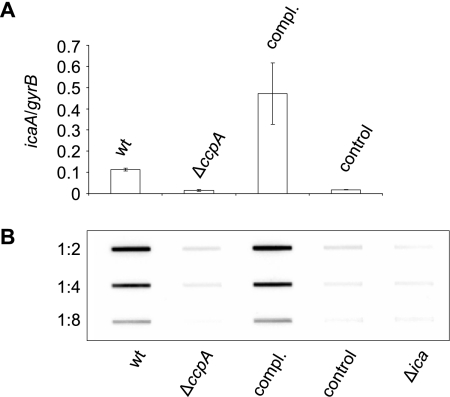

Effect of CcpA on ica expression and PIA production.

To support our proposed effect of CcpA on PIA production, we quantified the icaA transcription and determined the PIA production of SA113 and its ΔccpA mutant KS66 after 2 h (early exponential growth phase) and 8 h (stationary phase) of growth. Monitoring the icaA transcription after 2 h of growth in TSB supplemented with 1% glucose revealed a clear difference between SA113 and KS66, with SA113 producing 0.113 ± 0.006 copy of icaA per copy of gyrB, while deletion of ccpA resulted in a sevenfold reduction in icaA transcription (0.015 ± 0.004 copy of icaA per copy of gyrB for KS66), as compared to the wild type (P < 0.01). trans-Complementation of KS66 with pMST1 strongly increased icaA transcription (0.47 ± 0.144 copy of icaA per copy of gyrB), while transformation of KS66 with the empty control plasmid pAW17 did not alter the icaA expression of the mutant (0.018 ± 0.002 copy of icaA per copy of gyrB) (Fig. 4 A). Surprisingly, after 8 h of growth, icaA transcript levels were found to be strongly reduced and no longer differed significantly between SA113 and KS66 (0.001 ± 0.0004 copy of icaA per copy of gyrB for SA113 and 0.004 ± 0.004 copy of icaA per copy of gyrB for KS66; P > 0.05). Analysis of the PIA production in SA113 and its ΔccpA mutant KS66 identified significant amounts of PIA only in SA113 but not in KS66 (Fig. 4B). In line with our transcriptional data, PIA was only detectable during the early exponential growth phase (2 h), but not after 8 h of growth (data not shown). trans-Complementation of KS66 with pMST1 restored PIA production, while transformation of KS66 with pAW17 was found to have no effect, signaling that CcpA is indeed influencing ica transcription and PIA production in SA113.

FIG. 4.

(A) icaA transcription after 2 h of growth in TSB supplemented with 1% glucose. (B) Slot blot analysis of the PIA production after 2 h of growth in TSB supplemented with 1% glucose. PIA extracts were diluted as indicated. wt, wild-type strain SA113; ΔccpA, strain KS66; compl., strain KS66 complemented with pMST1; control, strain KS66 containing pAW17.

Effect of CcpA on TCA cycle genes.

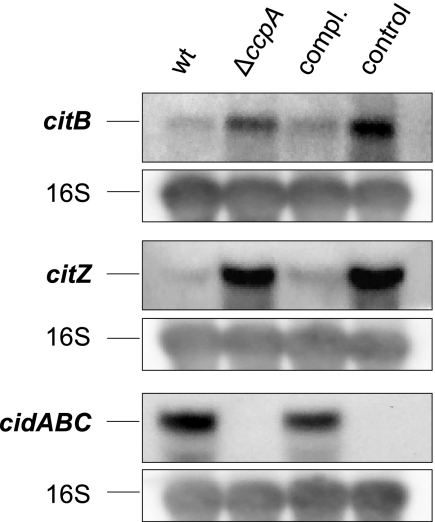

Based on the observations of Vuong and coworkers (56a), who found that decreased tricarboxylic acid (TCA) activity was associated with increased PIA production in S. epidermidis, and on the findings of Kim et al. (28), showing that transcription of the genes for the TCA cycle enzymes CitB (aconitase) and CitZ (citrate synthase) are influenced by CcpA in Bacillus subtilis, we monitored the effect of CcpA on the transcription of citB and citZ in S. aureus under biofilm inducing conditions. Similar to the findings of Vuong et al. (56a) and Kim et al. (28), we found a strong increase in citB and citZ transcription in KS66 during the early exponential growth phase (Fig. 5), and trans-complementation of the ΔccpA mutant with pMST1 reduced citB and citZ transcription to levels seen in the wild type. We found a putative cre (catabolite-responsive element) site 27 bp upstream of the citZ open reading frame (TgTGAAAGCcATTTCATA; capital letters indicate nucleotides that correspond to the cre site consensus of B. subtilis [38]), suggesting that CcpA affects the transcription of citZ directly. The effect of CcpA on citB expression, on the other hand, appears to be indirect because such an element is missing in front of, or within, citB, similar to the situation found in B. subtilis (28).

FIG. 5.

Northern blot analysis of citB, citZ, and cidABC transcription after 2 h of growth in TSB supplemented with 1% glucose. A 16S rRNA gene probe was used for hybridization as a loading control. wt, wild-type strain SA113; ΔccpA, strain KS66; compl., strain KS66 complemented with pMST1; control, strain KS66 containing pAW17.

Effect of CcpA on the transcription of selected factors known to be involved in the regulation of biofilm formation.

A series of genetic loci have been identified to influence the primary attachment and/or the cellular accumulation process in S. aureus in addition to the ica operon (reviewed by O'Gara [39]) and Tu Quoc et al. [55]). Our special interest focused on the impact of CcpA on the transcription of (i) rbf, due to its demonstrated influence on biofilm formation in response to glucose and salt (32); (ii) sarA, since the inactivation of sarA was shown to abolish biofilm formation in SA113 (1); (iii) atl and cidA, since they were shown to contribute to DNA release and biofilm development (4, 26, 44); (iv) mgrA, an important regulator of autolysis, which has recently been shown to be involved in biofilm formation (55); and (v) arlRS, another regulator of autolysis and cell division (21), since our computational analysis identified a putative cre (AATtTAAACGTAAACAAA; capital letters indicate nucleotides that correspond to the cre consensus of B. subtilis [38]) 95 bp downstream of the arlRS transcriptional start site (21a). We therefore analyzed the impact of CcpA on the transcription of arlRS, atl, mgrA, rbf, cidABC, and the sarA locus by monitoring the expression of these genes during the early exponential growth phase by Northern blot analysis. These assays revealed no apparent differences in arlRS, mgrA, rbf, or sarA transcription between the wild-type strain and its corresponding ΔccpA mutant, suggesting that CcpA is not affecting the regulation of these genes (data not shown). The investigation of the effect of CcpA on atl transcriptional levels suggested a tendency toward higher atl expression in the wild type than in the mutant, though total amounts of transcripts varied widely between separate experiments (data not shown).

However, we found a clear effect of CcpA on cidABC transcription, with SA113 producing significant amounts of cidABC, while no transcript was observed in KS66 (Fig. 5), and trans-complementation of the ΔccpA mutant with pMST1 led to the production of cidABC transcripts again. The acetic acid concentration at the time point of sampling for Northern blot analysis was 2 mM in the culture supernatant of both the wild type and mutant. Because the acetic acid concentration was lower than the concentration required for cidA induction (30 mM) according to reference 45, and the concentrations were identical in the wild type and mutant, we suggest that there may exist additional factors which can induce cidA transcription. As mutation of cidA has been associated with reduced autolysis (41), we analyzed the effect of the ccpA mutation on Triton X-induced autolysis. The wild type showed slightly faster autolysis, with 88% ± 9.0% of the cells lysed after 2 h, while the mutant showed only 66% ± 3.7% lysis at this time point. When trans-complementing the mutant with pMST1, lysis was partially restored to 72% ± 6.3% after 2 h.

Conclusion.

The rapid adaptation to environmental and nutritional conditions is central to the success of S. aureus as pathogen. The utilization of glucose as the preferred carbon source is controlled in S. aureus by CcpA, the mediator of carbon catabolite repression, which was shown earlier to promote the expression of selected virulence factors, increase the expression of oxacillin resistance, and repress capsule synthesis (50). The role of CcpA as a mediator of biofilm formation in the presence of glucose adds a further important function to CcpA, contributing to staphylococcal virulence and persistence. The positive impact of CcpA on biofilm formation in S. aureus is partly in contrast to observations made in B. subtilis (7, 53), where CcpA, depending on the growth medium, was found to repress biofilm formation. However, biofilm formation in S. aureus differs widely from biofilm formation in B. subtilis (8), which in the latter bacterium is closely related to sporulation. The S. aureus biofilm was shown here to have a complex composition, including PIA, proteinaceous factors, and eDNA. CcpA had an impact on at least two of these components: through upregulation of the ica operon, which is involved in PIA synthesis; and through upregulation of cidA, coding for the holin CidA, postulated to be involved in the release of eDNA. Regulation of these genes, which are not accompanied by a cre site, may have occurred indirectly, as a consequence of the downregulation of the TCA cycle through repression of citB and citZ, with citZ being preceded by a typical cre consensus sequence recognized by CcpA. These findings confirm the reported role of downregulation of the TCA cycle in biofilm formation (28). The apparent correlation between oxacillin resistance and the capacity to form a biofilm, as observed in some methicillin-resistant S. epidermidis strains (10), exists also in S. aureus and may be linked over CcpA.

Inactivation of CcpA in S. aureus, incapacitating biofilm formation, reducing the expression of secreted virulence factors and lowering the expression of oxacillin resistance, makes it an important player in overall staphylococcal virulence and antibiotic resistance. These findings underline the important linkage of metabolism to the envelope composition, virulence, and resistance in S. aureus.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation grant 31-117707, the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Bi 1350/1-1 Wo 578/5-1), and European Community grant EU-LSH-CT2003-50335 (BBW 03.0098).

We thank R. Landmann (Basel, Switzerland) and F. Götz (Tübingen, Germany) for providing the ica mutant of strain SA113. We thank H. Hilbi (ETH, Zurich, Switzerland) for providing the flow cell machinery and especially T. Spirig for his assistance in performing the flow cell experiments.

Editor: A. J. Bäumler

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 10 March 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beenken, K. E., J. S. Blevins, and M. S. Smeltzer. 2003. Mutation of sarA in Staphylococcus aureus limits biofilm formation. Infect. Immun. 714206-4211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beenken, K. E., P. M. Dunman, F. McAleese, D. Macapagal, E. Murphy, S. J. Projan, J. S. Blevins, and M. S. Smeltzer. 2004. Global gene expression in Staphylococcus aureus biofilms. J. Bacteriol. 1864665-4684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Begun, J., J. M. Gaiani, H. Rohde, D. Mack, S. B. Calderwood, F. M. Ausubel, and C. D. Sifri. 2007. Staphylococcal biofilm exopolysaccharide protects against Caenorhabditis elegans immune defenses. PLoS Pathog. 3e57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biswas, R., L. Voggu, U. K. Simon, P. Hentschel, G. Thumm, and F. Götz. 2006. Activity of the major staphylococcal autolysin Atl. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 259260-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caiazza, N. C., and G. A. O'Toole. 2003. Alpha-toxin is required for biofilm formation by Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 1853214-3217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cerca, N., K. K. Jefferson, T. Maira-Litrán, D. B. Pier, C. Kelly-Quintos, D. A. Goldmann, J. Azeredo, and G. B. Pier. 2007. Molecular basis for preferential protective efficacy of antibodies directed to the poorly acetylated form of staphylococcal poly-N-acetyl-β-(1-6)-glucosamine. Infect. Immun. 753406-3413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chagneau, C., and M. H. J. Saier. 2004. Biofilm-defective mutants of Bacillus subtilis. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 8177-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chai, Y., F. Chu, R. Kolter, and R. Losick. 2008. Bistability and biofilm formation in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 67254-263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chaignon, P., I. Sadovskaya, C. Ragunath, N. Ramasubbu, J. B. Kaplan, and S. Jabbouri. 2007. Susceptibility of staphylococcal biofilms to enzymatic treatments depends on their chemical composition. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 75125-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9a.Chan, P. F., and S. J. Foster. 1998. Role of SarA in virulence determinant production and environmental signal transduction in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 1806232-6241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christensen, G. D., L. M. Baddour, B. M. Madison, J. T. Parisi, S. N. Abraham, D. L. Hasty, J. H. Lowrance, J. A. Josephs, and A. W. Simpson. 1990. Colonial morphology of staphylococci on Memphis agar: phase variation of slime production, resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics, and virulence. J. Infect. Dis. 1611153-1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.CLSI. 2005. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing: 15th informational supplement. CLSI/NCCLS document M100-S15. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, Pa.

- 12.Corrigan, R. M., D. Rigby, P. Handley, and T. J. Foster. 2007. The role of Staphylococcus aureus surface protein SasG in adherence and biofilm formation. Microbiology 1532435-2446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cramton, S. E., C. Gerke, N. F. Schnell, W. W. Nichols, and F. Götz. 1999. The intercellular adhesion (ica) locus is present in Staphylococcus aureus and is required for biofilm formation. Infect. Immun. 675427-5433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cramton, S. E., M. Ulrich, F. Götz, and G. Döring. 2001. Anaerobic conditions induce expression of polysaccharide intercellular adhesin in Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis. Infect. Immun. 694079-4085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dubrac, S., I. G. Boneca, O. Poupel, and T. Msadek. 2007. New insights into the WalK/WalR (YycG/YycF) essential signal transduction pathway reveal a major role in controlling cell wall metabolism and biofilm formation in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 1898257-8269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fan, X., Y. Liu, D. Smith, L. Konermann, K. W. M. Siu, and D. Golemi-Kotra. 2007. Diversity of penicillin-binding proteins: resistance factor FmtA of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Biol. Chem. 28235143-35152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fitzpatrick, F., H. Humphreys, and J. P. O'Gara. 2006. Environmental regulation of biofilm development in methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus clinical isolates. J. Hosp. Infect. 62120-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fitzpatrick, F., H. Humphreys, and J. P. O'Gara. 2005. Evidence for icaADBC-independent biofilm development mechanism in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clinical isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 431973-1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flückiger, U., M. Ulrich, A. Steinhuber, G. Döring, D. Mack, R. Landmann, C. Goerke, and C. Wolz. 2005. Biofilm formation, icaADBC transcription, and polysaccharide intercellular adhesin synthesis by staphylococci in a device-related infection model. Infect. Immun. 731811-1819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Foster, T. J., and M. Hook. 1998. Surface protein adhesins of Staphylococcus aureus. Trends Microbiol. 6484-488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fournier, B., and D. C. Hooper. 2000. A new two-component regulatory system involved in adhesion, autolysis, and extracellular proteolytic activity of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 1823955-3964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21a.Fournier, B., A. Klier, and G. Rapoport. 2001. The two-component system ArlS-ArlR is a regulator of virulence gene expression in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 41247-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Götz, F. 2002. Staphylococcus and biofilms. Mol. Microbiol. 431367-1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gross, M., S. E. Cramton, F. Götz, and A. Peschel. 2001. Key role of teichoic acid net charge in Staphylococcus aureus colonization of artificial surfaces. Infect. Immun. 693423-3426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heilmann, C., M. Hussain, G. Peters, and F. Götz. 1997. Evidence for autolysin-mediated primary attachment of Staphylococcus epidermidis to a polystyrene surface. Mol. Microbiol. 241013-1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iordanescu, S., and M. Surdeanu. 1976. Two restriction and modification systems in Staphylococcus aureus NCTC8325. J. Gen. Microbiol. 96277-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Izano, E. A., M. A. Amarante, W. B. Kher, and J. B. Kaplan. 2008. Differential roles of poly-N-acetylglucosamine surface polysaccharide and extracellular DNA in Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74470-476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jankovic, I., and R. Brückner. 2007. Carbon catabolite repression of sucrose utilization in Staphylococcus xylosus: catabolite control protein CcpA ensures glucose preference and autoregulatory limitation of sucrose utilization. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 12114-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim, H.-J., A. Roux, and A. L. Sonenshein. 2002. Direct and indirect roles of CcpA in regulation of Bacillus subtilis Krebs cycle genes. Mol. Microbiol. 45179-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Knobloch, J., M. Horstkotte, H. Rohde, and D. Mack. 2002. Evaluation of different detection methods of biofilm formation in Staphylococcus aureus. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 191101-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Komatsuzawa, H., K. Ohta, H. Labischinski, M. Sugai, and H. Suginaka. 1999. Characterization of fmtA, a gene that modulates the expression of methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 432121-2125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lasa, I., and J. R. Penades. 2006. Bap: a family of surface proteins involved in biofilm formation. Res. Microbiol. 15799-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lim, Y., M. Jana, T. T. Luong, and C. Y. Lee. 2004. Control of glucose- and NaCl-induced biofilm formation by rbf in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 186722-729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mack, D., P. Becker, I. Chatterjee, S. Dobinsky, J. K. Knobloch, G. Peters, H. Rohde, and M. Herrmann. 2004. Mechanisms of biofilm formation in Staphylococcus epidermidis and Staphylococcus aureus: functional molecules, regulatory circuits, and adaptive responses. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 294203-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mack, D., W. Fischer, A. Krokotsch, K. Leopold, R. Hartmann, H. Egge, and R. Laufs. 1996. The intercellular adhesin involved in biofilm accumulation of Staphylococcus epidermidis is a linear β-1,6-linked glucosaminoglycan: purification and structural analysis. J. Bacteriol. 178175-183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maira-Litrán, T., A. Kropec, C. Abeygunawardana, J. Joyce, G. Mark III, D. A. Goldmann, and G. B. Pier. 2002. Immunochemical properties of the staphylococcal poly-N-acetylglucosamine surface polysaccharide. Infect. Immun. 704433-4440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McCallum, N., H. Karauzum, R. Getzmann, M. Bischoff, P. Majcherczyk, B. Berger-Bächi, and R. Landmann. 2006. In vivo survival of teicoplanin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and fitness cost of teicoplanin resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 502352-2360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McKenney, D., K. L. Pouliot, Y. Wang, V. Murthy, M. Ulrich, G. Döring, J. C. Lee, D. A. Goldmann, and G. B. Pier. 1999. Broadly protective vaccine for Staphylococcus aureus based on an in vivo-expressed antigen. Science 2841523-1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miwa, Y., A. Nakata, A. Ogiwara, M. Yamamoto, and Y. Fujita. 2000. Evaluation and characterization of catabolite-responsive elements (cre) of Bacillus subtilis. Nucleic Acids Res. 281206-1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O'Gara, J. P. 2007. ica and beyond: biofilm mechanisms and regulation in Staphylococcus epidermidis and Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 270179-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O'Neill, E., C. Pozzi, P. Houston, D. Smyth, H. Humphreys, D. A. Robinson, and J. P. O'Gara. 2007. Association between methicillin susceptibility and biofilm regulation in Staphylococcus aureus isolates from device-related infections. J. Clin. Microbiol. 451379-1388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Patton, T. G., K. C. Rice, M. K. Foster, and K. W. Bayles. 2005. The Staphylococcus aureus cidC gene encodes a pyruvate oxidase that affects acetate metabolism and cell death in stationary phase. Mol. Microbiol. 561664-1674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Qin, Z., Y. Ou, L. Yang, Y. Zhu, T. Tolker-Nielsen, S. Molin, and D. Qu. 2007. Role of autolysin-mediated DNA release in biofilm formation of Staphylococcus epidermidis. Microbiology 1532083-2092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Resch, A., R. Rosenstein, C. Nerz, and F. Götz. 2005. Differential gene expression profiling of Staphylococcus aureus cultivated under biofilm and planktonic conditions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 712663-2676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rice, K. C., E. E. Mann, J. L. Endres, E. C. Weiss, J. E. Cassat, M. S. Smeltzer, and K. W. Bayles. 2007. The cidA murein hydrolase regulator contributes to DNA release and biofilm development in Staphylococcus aureus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1048113-8118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rice, K. C., J. B. Nelson, T. G. Patton, S.-J. Yang, and K. W. Bayles. 2005. Acetic acid induces expression of the Staphylococcus aureus cidABC and lrgAB murein hydrolase regulator operons. J. Bacteriol. 187813-821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rohde, H., E. C. Burandt, N. Siemssen, L. Frommelt, C. Burdelski, S. Wurster, S. Scherpe, A. P. Davies, L. G. Harris, M. A. Horstkotte, J. K.-M. Knobloch, C. Ragunath, J. B. Kaplan, and D. Mack. 2007. Polysaccharide intercellular adhesin or protein factors in biofilm accumulation of Staphylococcus epidermidis and Staphylococcus aureus isolated from prosthetic hip and knee joint infections. Biomaterials 281711-1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rohde, H., C. Burdelski, K. Bartscht, M. Hussain, F. Buck, M. A. Horstkotte, J. K.-M. Knobloch, C. Heilmann, M. Herrmann, and D. Mack. 2005. Induction of Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilm formation via proteolytic processing of the accumulation-associated protein by staphylococcal and host proteases. Mol. Microbiol. 551883-1895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rossi, J., M. Bischoff, A. Wada, and B. Berger-Bächi. 2003. MsrR, a putative cell envelope-associated element involved in Staphylococcus aureus sarA attenuation. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 472558-2564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sadovskaya, I., E. Vinogradov, S. Flahaut, G. Kogan, and S. Jabbouri. 2005. Extracellular carbohydrate-containing polymers of a model biofilm-producing strain, Staphylococcus epidermidis RP62A. Infect. Immun. 733007-3017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Seidl, K., M. Stucki, M. Ruegg, C. Goerke, C. Wolz, L. Harris, B. Berger-Bächi, and M. Bischoff. 2006. Staphylococcus aureus CcpA affects virulence determinant production and antibiotic resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 501183-1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shanks, R. M. Q., N. P. Donegan, M. L. Graber, S. E. Buckingham, M. E. Zegans, A. L. Cheung, and G. A. O'Toole. 2005. Heparin stimulates Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation. Infect. Immun. 734596-4606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Silvestri, L. G., and L. R. Hill. 1965. Agreement between deoxyribonucleic acid base composition and taxometric classification of gram-positive cocci. J. Bacteriol. 90136-140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stanley, N. R., R. A. Britton, A. D. Grossman, and B. A. Lazazzera. 2003. Identification of catabolite repression as a physiological regulator of biofilm formation by Bacillus subtilis by use of DNA microarrays. J. Bacteriol. 1851951-1957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Toledo-Arana, A., N. Merino, M. Vergara-Irigaray, M. Debarbouille, J. R. Penades, and I. Lasa. 2005. Staphylococcus aureus develops an alternative, ica-independent biofilm in the absence of the arlRS two-component system. J. Bacteriol. 1875318-5329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tu Quoc, P. H., P. Genevaux, M. Pajunen, H. Savilahti, C. Georgopoulos, J. Schrenzel, and W. L. Kelley. 2007. Isolation and characterization of biofilm formation-defective mutants of Staphylococcus aureus. Infect. Immun. 751079-1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Valle, J., A. Toledo-Arana, C. Berasain, J.-M. Ghigo, B. Amorena, J. R. Penades, and I. Lasa. 2003. SarA and not SigB is essential for biofilm development by Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 481075-1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56a.Vuong, C., J. B. Kidder, E. R. Jacobson, M. Otto, R. A. Proctor, and G. A. Somerville. 2005. Staphylococcus epidermidis polysaccharide intercellular adhesin production significantly increases during tricarboxylic acid cycle stress. J. Bacteriol. 1872967-2973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Weidenmaier, C., J. F. Kokai-Kun, S. A. Kristian, T. Chanturiya, H. Kalbacher, M. Gross, G. Nicholson, B. Neumeister, J. J. Mond, and A. Peschel. 2004. Role of teichoic acids in Staphylococcus aureus nasal colonization, a major risk factor in nosocomial infections. Nat. Med. 10243-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wen, Z. T., and R. A. Burne. 2002. Functional genomics approach to identifying genes required for biofilm development by Streptococcus mutans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 681196-1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang, S.-J., K. C. Rice, R. J. Brown, T. G. Patton, L. E. Liou, Y. H. Park, and K. W. Bayles. 2005. A LysR-type regulator, CidR, is required for induction of the Staphylococcus aureus cidABC operon. J. Bacteriol. 1875893-5900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]