Abstract

The CD8 coreceptor is important for positive selection of major histocompatibility complex I (MHC-I)-restricted thymocytes and in the generation of pathogen-specific T cells. However, the requirement for CD8 in these processes may not be essential. We previously showed that mice lacking β2-microglobulin are highly susceptible to tumors induced by mouse polyoma virus (PyV), but CD8-deficient mice are resistant to these tumors. In this study, we show that CD8-deficient mice also control persistent PyV infection as efficiently as wild-type mice and generate a substantial virus-specific, MHC-I-restricted, T-cell response. Infection with vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV), which is acutely cleared, also recruited antigen-specific, MHC-I-restricted T cells in CD8-deficient mice. Yet, unlike in VSV infection, the antiviral MHC-I-restricted T-cell response to PyV has a prolonged expansion phase, indicating a requirement for persistent infection in driving T-cell inflation in CD8-deficient mice. Finally, we show that the PyV-specific, MHC-I-restricted T cells in CD8-deficient mice, while maintained long term at near-wild-type levels, are short lived in vivo and have extremely narrow T-cell receptor repertoires. These findings provide a possible explanation for the resistance of CD8-deficient mice to PyV-induced tumors and have implications for the maintenance of virus-specific MHC-I-restricted T cells during persistent infection.

CD8 T cells are critical mediators of immune surveillance for viral infections. Antiviral CD8 T cells express T-cell receptors (TCRs) that recognize virus-derived oligopeptides fitted into a solvent-accessible groove formed by the α1 and α2 domains of major histocompatibility complex I (MHC-I) molecules. The topology defined by a particular peptide-MHC-I (pMHC-I) complex creates a ligand for a select number of clonally distributed TCRs. The α chain of CD8 molecules, which are expressed at the cell surface as αα homodimers or αβ heterodimers, contacts a nonpolymorphic site in the juxtamembrane α3 domain of MHC-I heavy chains. CD8 operates as a TCR coreceptor by stabilizing T-cell binding to pMHC-I ligands and by amplifying proximal TCR signal transduction via colocalizing the tyrosine kinase p56lck, which is associated with the cytoplasmic domain of the CD8α chain. By these mechanisms, engagement of the CD8 coreceptor can dramatically enhance sensitivity for antigenic peptides and thereby compensate for low-affinity TCRs (20, 23). Centrally, CD8 molecules promote efficient positive selection of MHC-I-restricted thymocytes. In the T-cell periphery, once CD8-amplified TCR signaling reaches a sufficient activation threshold, CD8 T cells mobilize antiviral effector functions, including cytokine production and cytotoxic activity.

The requirement for CD8 coreceptors in the selection and generation of MHC-I-restricted T-cell responses, however, may not be absolute. Mice genetically disrupted for CD8α gene expression (CD8KO mice) exhibit a profound defect in mounting MHC-I-restricted T-cell responses against viruses that are acutely cleared in wild-type mice (3, 14). However, cytotoxic CD4− T cells in CD8KO mice have previously been shown to be capable of rejecting MHC-I-disparate skin grafts (8). In a recent report of a familial CD8α gene missense mutation, three CD8-deficient siblings, of which two were asymptomatic and one suffered recurrent non-life-threatening bacterial infections, were shown to have high frequencies of circulating CD4−CD8−TCRαβ+ T cells that phenotypically resembled effector CD8 cytotoxic T lymphocytes; whether these double-negative T cells were MHC-I restricted was not addressed (10).

Using the oncogenic mouse polyoma virus (PyV) infection model, we came across the unexpected finding that CD8KO mice were largely resistant to PyV-induced tumors, although β2 microglobulin-deficient mice were highly susceptible to PyV tumorigenesis (13). This observation led us to hypothesize that PyV might elicit an MHC-I-restricted T-cell response in CD8KO mice. In this study, we demonstrate that CD8KO mice infected by PyV indeed generate an MHC-I-restricted virus-specific T-cell response. This antiviral T-cell response, though, was found to differ from that elicited in wild-type mice in terms of the time course of expansion, functional competence, and TCR repertoire diversity. Thus, CD8 coreceptors are dispensable for generating antiviral MHC-I-restricted T-cell responses and provide a possible explanation for the PyV-induced tumor resistance of CD8KO mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

C57BL/6 (B6) mice were purchased from the National Cancer Institute. CD8atm1Mak mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and bred at Emory University Department of Animal Resources. All animal protocols were conducted according to the guidelines established by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and the Department of Animal Resources of Emory University. All mice were between 6 and 12 weeks of age at the time of infection.

Viruses.

Stocks of PyV (strain A2) and PyV.OVA-I were prepared in baby mouse kidney cells, as described previously by Lukacher and Wilson (28). Mice were injected subcutaneously (s.c.) in hind footpads with 2 × 106 PFU of virus. Recombinant PyV.OVA-I was generated through the insertion of the SIINFEKL coding sequence in frame at a unique BlpI restriction site in the coding region of middle T antigen (Ag) (4). SIINFEKL-encoding fragments were generated with high-fidelity Taq polymerase (Invitrogen) using a forward overhanging primer also encoding the BlpI restriction site (5′-GTGTTGCTGAGCATAATCAACTTCGAAAAACTGAGCCCGATGACAGCATATCC-3′) and a reverse primer encoding an EcoRI site (5′-TCAGAATTCGGGCCTGAACTTCC-3′); restriction sites are underlined. The resulting PCR product was cloned into a unique BlpI/EcoRI site of a pUC19 plasmid containing the small fragment of a BamHI/EcoRI-digested PyV genome. The large fragment was also cloned into pUC19. The small and large fragments were excised from pUC19, ligated to generate full-length PyV DNA, and transfected (using Lipofectamine 2000 [Invitrogen]) into baby mouse kidney cells. Recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus encoding the Db-restricted LT359-368 epitope (rVSV-LT359) was generated as described previously (2). The tail veins of the mice were injected intravenously (i.v.) with 1 × 106 PFU of rVSV-LT359.

Synthetic peptides.

The LT359-368Abu (SAVKNY[Abu]SKL) peptide, in which the cysteine residue at position 7 was replaced with α-aminobutyric acid, a thiol-less cysteine analog residue, was synthesized by the solid-phase method using F-moc chemistries (Emory University Microchemical Core Facility) and high-pressure liquid chromatography purified to more than 90% purity. For simplicity, the LT359-368Abu peptide is referred to as LT359 peptide.

TaqMan real-time PCR to quantitate PyV DNA.

DNA isolation and TaqMan PCR were performed as described previously (21). PyV DNA quantity is expressed in genome copies per milligram of tissue and is calculated based on a standard curve of known PyV genome copy number versus the threshold cycle of detection. The detection limit with this assay is 10 copies of genomic viral DNA.

Flow cytometry.

One million cells per sample were stained in phosphate-buffered saline containing 2% fetal bovine serum and 0.1% sodium azide. Antibody staining was performed at 4°C for 30 min; allophycocyanin-conjugated DbLT359 tetramer (21) staining was performed at room temperature for 30 min. Cells were surface stained with a fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-CD4 (clone GK1.5) (BD Biosciences), phycoerythrin-Cy7-conjugated monoclonal antibody (MAb) specific for CD3ɛ (eBioscience), and phycoerythrin-conjugated MAbs specific for TCRβ (clone H57-597), KLRG1, CD127, PD-1, and rat immunoglobulin G isotype controls (eBioscience). TCR Vβ domain usage was determined by intracellular staining using a fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated panel of MAbs (BD Pharmingen). This approach was developed due to MHC tetramer-induced downregulation of TCRs on CD8KO T cells. After staining with DbLT359 tetramer and CD3 and CD4 MAbs, cells were permeabilized with Cytofix/Cytoperm and stained intracellularly with anti-Vβ MAbs. Samples were acquired on a FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences), and data were analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star).

Intracellular staining.

Cells were stimulated directly ex vivo with the indicated concentration of LT359 peptide and then stained for surface CD3, CD4, and intracellular cytokines as described previously (21).

DbLT359 tetramer dilution assays.

DbLT359 tetramer was prepared in twofold serial dilutions from 1:100 to 1:25,600. B6 and CD8KO spleen cells were stained at room temperature with the diluted tetramer and MAbs specific for CD3ɛ and CD4 for 30 min at room temperature. The cells were washed, fixed with 4% formaldehyde, and analyzed by flow cytometry.

In vivo cytotoxicity assays.

B6 mice infected with PyV 21 days or 6 weeks previously were tested for in vivo killing of LT359-368Abu peptide-pulsed naïve B6 spleen cells over a 4-h period, as described previously (7).

Adoptive transfer.

B6 and CD8KO mice were injected in the footpads with 2 × 106 PFU PyV. Three weeks after infection, spleen cells were incubated for 1 h at 37°C in flasks coated with goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). Nonadherent cells were labeled with 2.5 μM 5,6-carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE) (Invitrogen) for 10 min at 37°C. A total of 40 × 106 cells was injected i.v. into infection-matched B6 or CD8KO hosts. CD3+ DbLT359 tetramer+ cells in the blood were tracked over time for CFSE fluorescence intensity and as a frequency of total donor CD3+ cells.

Statistics.

Statistical significance was determined by unpaired Student's t test, assuming unequal variances. A P value of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. Linear and nonlinear regression analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism, version 4.0c (GraphPad Software, Inc.).

RESULTS

PyV infection elicits an MHC-I-restricted T-cell response in CD8KO mice.

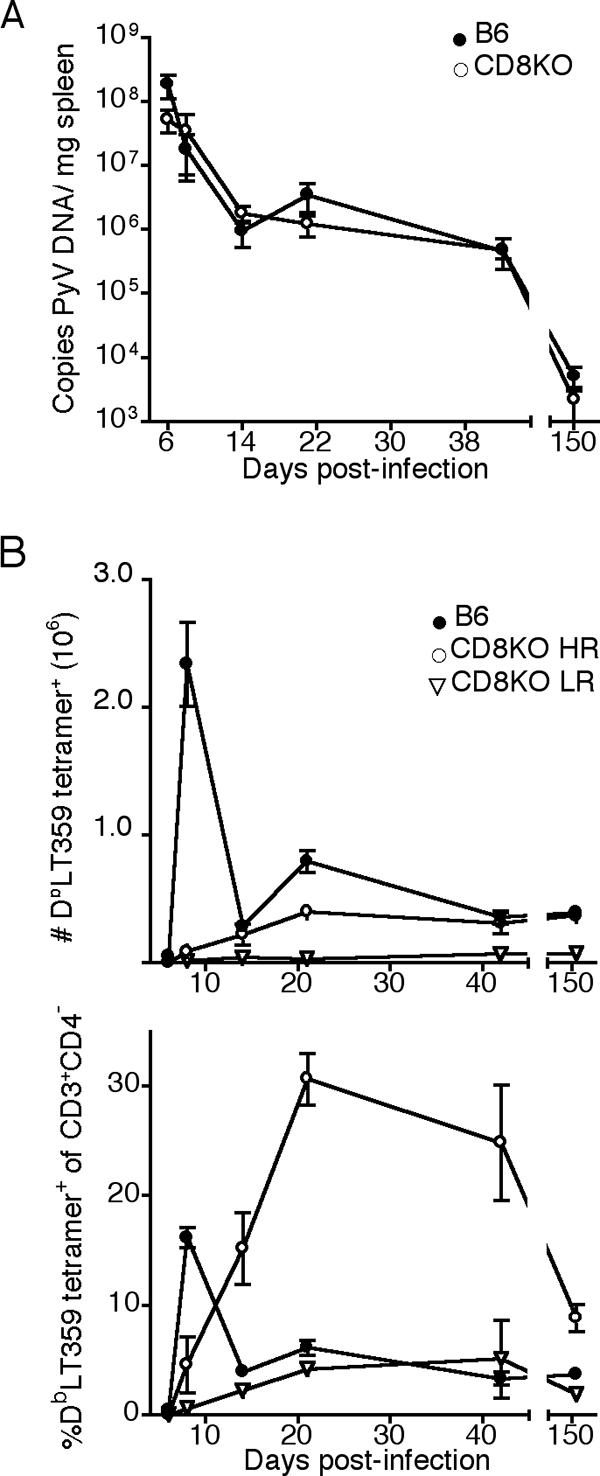

Because B6 and CD8KO mice are both resistant to PyV-induced tumors (13), we compared their abilities to control PyV replication. Quantitative PCR assays for PyV DNA in spleen (Fig. 1A) and kidney (data not shown) revealed no differences in viral DNA load between B6 and CD8KO mice through acute and persistent phases of infection. Thus, CD8 deficiency has no overt effect on the capacity of the host to control PyV load.

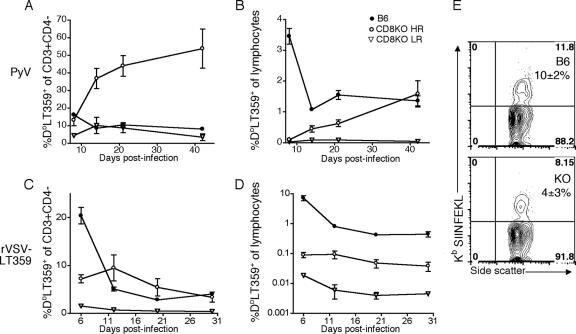

FIG. 1.

CD8KO mice control PyV infection and generate PyV-specific, MHC-I-restricted, T-cell responses. B6 and CD8KO mice received 2 × 106 PFU of PyV s.c. (A) Splenic PyV DNA copy number at the indicated day p.i. (B) Number (top panel) and frequency (bottom panel) of splenic CD3+CD4− DbLT359 tetramer+ T cells at the indicated day p.i. Data are the means for three (B6) or six (CD8KO) mice per group and are representative of two (A) or three (B) experiments.

We next explored the possibility that virus-infected CD8KO mice might mount an MHC-I-restricted antiviral T-cell response. As shown in Fig. 1B, PyV-infected CD8KO mice indeed generated a T-cell response directed toward the dominant Db-restricted viral epitope, LT359-368, albeit one of lower magnitude than that of B6 mice. DbLT359 tetramer staining was specific, as Dbgp33 tetramers (which detect lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus [LCMV]-specific CD8 T cells [31]) did not bind T cells from either PyV-infected B6 or CD8KO mice (data not shown). In addition, small populations of CD3+CD4+ DbLT359 tetramer+ cells were detected in all B6 mice and infrequently in CD8KO mice at days 8 and 21 postinfection (p.i.), respectively (data not shown). These cells are likely an activated population that has upregulated CD4 upon costimulation (35).

The pattern of LT359-specific T-cell responses in CD8KO mice, however, departed dramatically from that seen in infected B6 mice. CD3+CD4− DbLT359 tetramer+ T cells progressively expanded to reach peak magnitude by 3 weeks p.i. and, as a population, did not contract (Fig. 1B, top panel). Although CD3+CD4− DbLT359 tetramer+ T cells were detected in all PyV-infected CD8KO mice, the magnitude of this Ag-specific T-cell response varied among individual animals. Approximately two-thirds of CD8KO mice, designated high responders (HRs), exhibited this anti-PyV MHC-I-restricted T-cell response, while the remaining mice showed a much lower number of DbLT359 tetramer+ cells; we termed these remaining mice low responders (LRs). LR-CD8KO mice had low frequencies (<8%) and numbers (<1 × 105) of LT359-specific T cells at all time points examined (Fig. 1B). Subdominant MHC-I-restricted anti-PyV T cells (21) were not observed in either HR- or LR-CD8KO mice (data not shown), presumably because their levels fell below detection by tetramer staining or peptide-stimulated intracellular cytokine staining and enzyme-linked immunospot assays for gamma interferon (IFN-γ) production. Failure to detect these subdominant T cells may also reflect an increased dependence on CD8 for binding pMHC than is needed for stabilizing DbLT359 tetramer binding. Notably, at their maximal point of expansion in HR-CD8KO mice, LT359-specific T cells comprised nearly a third of all splenic CD3+CD4− T cells (Fig. 1B, bottom panel). By 5 months p.i., B6 and HR-CD8KO mice had similar numbers of LT359-specific T cells (Fig. 1B, top panel). While numbers of LT359-specific T cells remained stable over time (Fig. 1B, top panel), the decline in the percentage of LT359-specific T cells in CD8KO mice at day 150 p.i. (Fig. 1B, bottom panel) can largely be accounted for by an observed twofold increase in total DbLT359 tetramer-negative CD3+CD4− frequencies in the day 150 p.i. mice compared to day 42 and day 21 p.i. mice; MHC-I tetramers for the two known subdominant PyV-specific CD8 T cells (21) did not stain spleen cells from these day 150 p.i. mice (data not shown). Acutely and persistently infected B6 mice, interestingly, did not have detectable CD3+CD4−CD8− DbLT359 tetramer+ T cells in the spleen or in the bone marrow, which is a site enriched in double-negative T cells (29, 36). Taken together, these data indicate that CD8 coreceptors are not essential for generating an MHC-I-restricted antiviral T-cell response.

Acutely cleared rVSV infection elicits an Ag-specific T-cell response in CD8KO mice.

We next asked whether the ability of CD8KO mice to mount MHC-I-restricted T-cell responses required repetitive Ag encounter, as in persistent virus infection, or was a unique feature of PyV infection. To address these questions, we compared the LT359-specific T-cell responses in B6 and CD8KO mice infected either by PyV or by rVSV-LT359, which is cleared after acute infection. As shown in Fig. 2A, circulating LT359-specific T cells in PyV-infected CD8KO mice approached roughly half of the total CD3+CD4− pool by 6 weeks p.i. This increase was not due to the attrition of non-PyV-specific CD3+CD4− T cells, as the frequency of this population remained stable through persistent infection (data not shown). As a fraction of total circulating lymphocytes, the frequency of LT359-specific T cells in HR-CD8KO mice eventually reached that of B6 mice by 6 weeks p.i. (Fig. 2B). A sizeable number of PyV-infected CD8KO mice fell into the LR category (Fig. 2A and B). Interestingly, this mouse-to-mouse variability in LT359-specific T-cell responses in PyV-infected CD8KO mice was recapitulated by rVSV-LT359 infection (Fig. 2C and D). Such individual variability in Ag-specific T-cell responses, in the context of heterologous viral infections, points toward peripheral TCR repertoire differences among CD8KO mice. Also, in contrast to the “inflationary” LT359-specific T-cell response in PyV-infected CD8KO mice, the response in HR-CD8KO mice to rVSV-LT359 infection declined over time (Fig. 2C). This result suggests that persistent Ag is required for the progressive increase of LT359-specific T cells.

FIG. 2.

Differences between PyV and VSV infection in the pattern of Ag-specific, MHC-I-restricted, T-cell responses in CD8KO mice. B6 and CD8KO mice received 2 × 106 PFU of PyV s.c. or 1 × 106 PFU of rVSV-LT359 i.v. CD3+CD4−DbLT359 tetramer+ cells were tracked in the blood of PyV-infected mice (A and B) or rVSV-LT359-infected mice (C and D) and were graphed as a frequency of total CD3+CD4− T cells or total lymphocytes. (E) B6 (top panel) and CD8KO mice (bottom panel) were infected with 2 × 106 PFU of PyV.OVA-I s.c. At day 8 p.i., frequencies of CD3+CD4−KbSIINFEKL tetramer+ cells in the blood were determined. The mean ± standard deviation of tetramer+ cells is indicated. Data are the means for three (B6) or six (CD8KO) mice per group and are representative of two (A to D) or one (E) experiment.

We next asked whether the capacity of CD8KO mice to generate an MHC-I-restricted response was limited to the LT359 epitope. CD8KO mice were inoculated with a recombinant PyV (encoding amino acids 257 to 264 of chicken ovalbumin [SIINFEKL]), which efficiently elicits a Kb-restricted T-cell response in B6 mice (Fig. 2E and data not shown). As shown in Fig. 2E, KbSIINFEKL tetramers stained T cells in CD8KO mice infected with this recombinant PyV. Thus, CD8KO mice are capable of mounting MHC-I-restricted T-cell responses to infection with unrelated viruses and directed to different specificities.

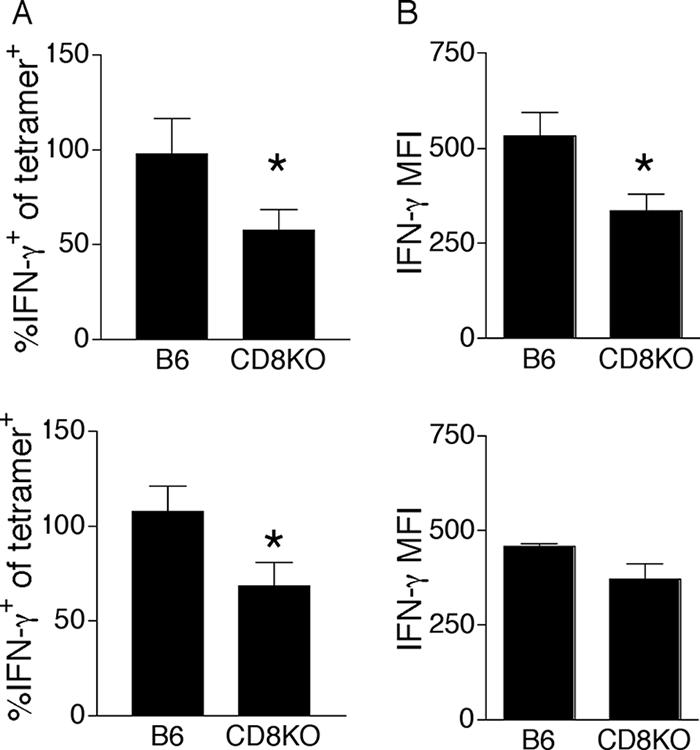

Functional deficits of MHC-I-restricted, PyV-specific T cells in CD8KO mice.

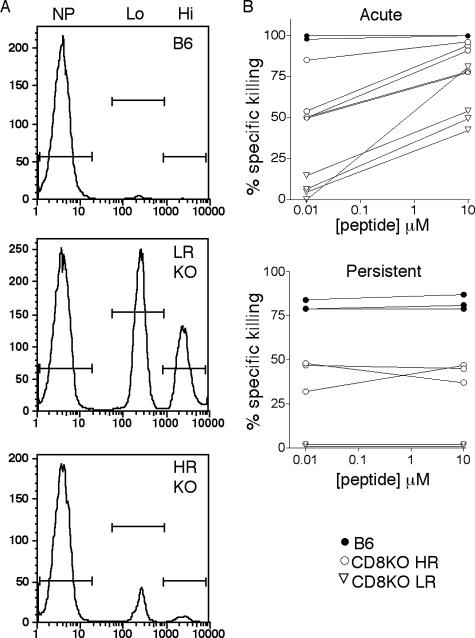

MHC-I-restricted PyV-specific T cells in CD8KO mice exhibited a defect in cytokine effector capability. At both day 21 (Fig. 3A, top panel) and 6 weeks p.i. (Fig. 3A, bottom panel), only 50 to 60% of DbLT359 tetramer+ splenic CD3+CD4− T cells in CD8KO mice produced IFN-γ after in vitro peptide stimulation, while nearly all DbLT359 tetramer+ T cells in B6 mice did so. Moreover, of those CD8KO T cells making IFN-γ, per-cell production was significantly lower than that in B6 mice at day 21 p.i. (Fig. 3B, top panel), although differences in IFN-γ production at 6 weeks p.i. were not statistically significant (Fig. 3B, bottom panel). The fraction of peptide-stimulated IFN-γ+ T cells coproducing either interleukin-2 or tumor necrosis factor alpha was the same for both CD8KO and B6 mice at both of these time points (data not shown). PyV-infected CD8KO mice were also capable of eliminating LT359 peptide-pulsed splenic target cells in vivo during both acute and persistent phases of infection, but with less efficiency and greater intermouse variability than those of infected B6 mice (Fig. 4). Individual differences in cytotoxic capabilities among CD8KO mice generally correlated with the magnitude of the LT359-specific T-cell response (Fig. 4B). Despite these differences in effector function, similar frequencies of CD127 (interleukin-7Rα), KLRG1, and PD-1 expression on DbLT359-specific T cells were obtained for B6 and CD8KO mice at day 21 (Fig. 5) and 6 weeks p.i. (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Partial dysfunction by PyV-specific MHC-I-restricted T cells in CD8KO mice. Spleen cells from mice infected 21 days (top panel) or 6 weeks (bottom panel) previously were stimulated with LT359 peptide (1.0 μM) and stained intracellularly for IFN-γ. The data are represented as the percentage of CD3+CD4− DbLT359 tetramer+ cells producing IFN-γ (A) and the MFI of IFN-γ staining (B). *, P value was ≤0.05. Data are the means for three to five mice per group and are representative of two experiments at each time point. Error bars indicate standard deviations.

FIG. 4.

MHC-I-restricted in vivo killing of peptide-pulsed targets by PyV-infected B6 and CD8KO mice. Naïve B6 spleen cells were pulsed with low (10 nM) or high (10 μM) concentrations of LT359 peptide or were left unpulsed. After PKH and CFSE labeling, the cells were injected i.v. into naïve B6 mice or B6 and CD8KO (KO) mice infected 21 days (acute) or 6 weeks (persistent) previously. After 4 h, spleens were analyzed by flow cytometry for remaining target cells. (A) Representative histograms for B6 mice and for LR and HR CD8KO mice gated on PKH+ spleen cells showing no peptide (NP), low-peptide (Lo), and high-peptide (Hi) populations. (B) Specific killing of peptide-pulsed targets versus peptide concentration during acute (top panel) and persistent (bottom panel) PyV infection. Data for day 21 p.i. are for B6 (n = 6) and CD8KO (n = 8) mice from two independent experiments. Data for 6 weeks p.i. are for three to five mice per group and are representative of two experiments.

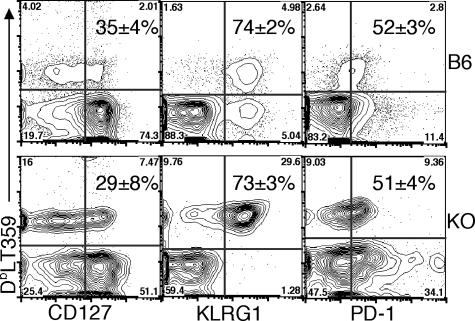

FIG. 5.

Phenotypic analysis of PyV-specific MHC-I-restricted T cells in B6 and CD8KO mice. Representative plots show CD127, KLRG-1, and PD-1 expression on CD3+CD4−DbLT359 tetramer+ spleen cells from B6 and CD8KO (KO) mice on day 21 p.i. Numbers indicate the means ± standard deviations of tetramer+ cells expressing the given activation marker. Data are the means for three (B6) or four (CD8KO) mice and are representative of two independent experiments.

PyV-specific T cells from wild-type and CD8KO mice have similar avidities.

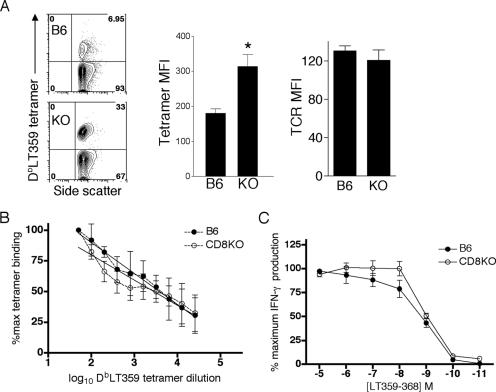

The efficiency with which a given Ag-specific CD8 T-cell population binds its cognate pMHC represents one measure of T-cell avidity (6, 9, 43). Interestingly, CD8-deficient T cells were better able to bind DbLT359 tetramers under conditions of ligand saturation, as shown by higher mean fluorescence intensities (MFI) (Fig. 6A, left and middle panels). TCR expression levels do not explain this difference, however, because DbLT359 tetramer+ T cells in B6 and CD8KO mice showed equivalent levels of staining by CD3ɛ (data not shown) and TCRβ chain MAbs (Fig. 6A, right panel). Moreover, DbLT359 tetramers stain CD3+CD4− cells from both HR-CD8KO and LR-CD8KO mice with similar MFI (data not shown), suggesting that LT359-specific T cells in these mice are not qualitatively different. Despite this difference in tetramer binding, when normalized to the number of spleen cells stained by saturating amounts of tetramer, spleen cells from PyV-infected CD8KO and B6 mice stained equivalently with DbLT359 tetramers over a broad titration range (Fig. 6B). Using intracellular IFN-γ as a readout of T-cell activation, we found that graded doses of LT359 peptide stimulated similar proportions of Ag-specific T cells in wild-type and CD8KO mice (Fig. 6C). Anti-CD8α inhibited IFN-γ production by LT359 peptide-stimulated spleen cells from B6 mice, indicating that CD8 molecules operate as coreceptors for these PyV-specific T cells (data not shown). An important caveat to these functional assays, however, is that only ∼50% of the LT359-specific T cells in CD8KO mice produce IFN-γ (Fig. 3A). Taken together, these data suggest that the presence or absence of CD8 does not appear to contribute to the avidity of the LT359-specific T-cell population, although a lack of coreceptor engagement is associated with impaired IFN-γ effector activity (Fig. 3).

FIG. 6.

Assessment of LT359-specific T-cell avidity of B6 and CD8KO mice. (A) Representative plots (left panel) of CD3+CD4− DbLT359 tetramer+ spleen cells, with means ± standard deviations of tetramer MFI (middle panel) and TCRβ-chain MAb (right panel) MFI of CD3+CD4− DbLT359 tetramer+ spleen cells at day 21 p.i. KO, CD8KO mice. *, P value was ≤0.05. (B) Spleen cells were stained with twofold serial dilutions of DbLT359 tetramer plus anti-CD3 and anti-CD4. The frequency of tetramer binding at each dilution was normalized to the percentage of binding at the lowest dilution. The data show an equivalent fit with both linear and nonlinear regression models, so the simpler linear model was selected (R2 − B6 = 0.804; R2 − KO = 0.713) which returned a common slope (−22.3) and y intercept (128.4). (C) Spleen cells were stimulated with the indicated concentrations of LT359 peptide and surface stained for CD3 and CD4 and intracellularly for IFN-γ. Data were normalized to the frequency of IFN-γ+ cells stimulated with 10 μM peptide. The LT359 peptide concentrations that elicited 50% IFN-γ production were 1.23 nM (B6) and 0.96 nM (CD8KO). Data are the means for three or four mice and are representative of two independent experiments. Error bars indicate standard deviations.

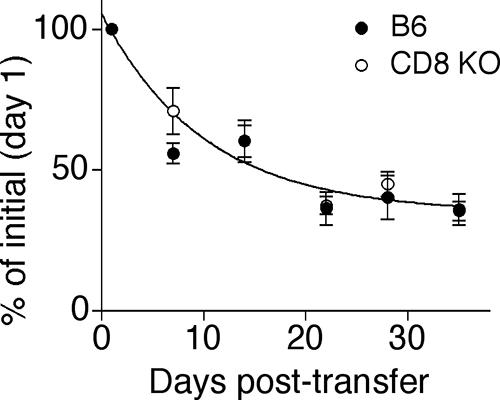

DbLT359-specific T-cell turnover rates are similar in B6 and CD8KO mice.

CFSE-labeled spleen cells from PyV-infected B6 and CD8KO mice at day 21 p.i. were transferred to infection-matched B6 and CD8KO recipients, respectively, and their survival and proliferation were monitored in the blood of individual mice. Based on the absence of CFSE dilution, neither wild-type nor CD8-deficient donor LT359-specific T cells underwent cell division over the 5-week period of examination (data not shown). As we have previously seen (39), there was progressive attrition of donor LT359-specific T cells in persistently infected B6 mice (Fig. 7). The same fate held for donor LT359-specific T cells in persistently infected CD8KO mice, with the survival curves for the transferred DbLT359 tetramer+ cells being statistically indistinguishable between CD8KO and B6 mice (Fig. 7). Thus, the absence of CD8 does not alter the turnover kinetics of chronic memory, MHC-I-restricted PyV-specific T cells.

FIG. 7.

Maintenance of LT359-specific T cells in B6 and CD8KO mice. At three weeks p.i., CFSE-labeled B6 and CD8KO spleen cells were transferred to infection-matched hosts and frequencies of CD3+ donor cells were tracked over time. The shared survival curve obtained by nonlinear regression analysis is shown. Values represent the means ± standard errors (error bars) of the means for three or four mice per group and are representative of two independent experiments.

LT359-specific T cells from PyV-infected CD8KO mice have highly restricted Vβ TCR usage.

Because thymic output of MHC-I-restricted TCRαβ+CD4−CD8− cells is reduced in CD8KO mice (15), we asked whether the absence of CD8 coreceptors would constrain peripheral T-cell repertoire diversity for PyV-specific MHC-I-restricted T cells. In naïve mice, Vβ expression profiles of CD4 T cells in B6 and CD8KO mice were diverse and largely overlapped (Fig. 8A, right panel), but the Vβ expression pattern of CD3+CD4− T cells in CD8KO mice departed significantly from that of B6 mice (Fig. 8A, left panel). This skewing of the TCR repertoire in CD8KO mice was dramatically revealed by Vβ MAb staining of LT359-specific T cells. As we previously showed (21), LT359-specific T cells in B6 mice displayed a diverse TCR Vβ profile that narrowed somewhat over the course of persistent infection (Fig. 8B and C, left panels). In marked contrast, during the expansion phase, the vast majority of DbLT359 tetramer+ T cells in CD8KO mice already expressed a very limited range of Vβ elements (Fig. 8B, right panel), which differed among individual mice and was still evident through late times after infection (Fig. 8C, right panel). These data suggest that CD8 deficiency limits TCR diversity either at the thymocyte selection stage or through preferential expansion of certain LT359-specific T-cell clonotypes during PyV infection.

FIG. 8.

Vβ TCR repertoire analysis of naïve and LT359-specific T cells from B6 and CD8KO mice. Spleen cells were stained with DbLT359 tetramer, anti-CD3, anti-CD4, and the indicated Vβ TCR MAbs. (A) Naïve CD3+CD4− (left panel) or CD3+CD4+ (right panel) T cells. (B) CD3+CD4− T cells at day 21 post-PyV infection from B6 (left panel) or CD8KO (right panel) mice. All commercially available MAbs specific for TCR Vβ chains were tested. For the sake of clarity, Vβ chains 8.3 through 17 are not shown, as they were not expressed by CD8-deficient LT359-specific T cells at day 21 p.i. (C) CD3+CD4− T cells at 6 weeks post-PyV infection from B6 (left panel) or CD8KO (right panel) mice. *, P value was ≤0.05. Data for naïve mice are the means for three animals per group. For PyV-infected mice, each bar pattern represents an individual animal.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrate that CD8KO mice infected by PyV generate a virus-specific, MHC-I-restricted, T-cell response. In contrast to the case for wild-type mice, PyV-specific MHC-I-restricted T cells in CD8KO mice were detectable only after a considerable lag and then progressively expanded in the majority of CD8KO mice. Ag persistence appeared to drive this expansion of MHC-I-restricted T cells, since such “inflation” did not occur following acute infection with an rVSV carrying the dominant CD8 T-cell PyV epitope. During the persistent phase of PyV infection, however, CD8KO and wild-type B6 mice maintained similar numbers of MHC-I-restricted dominant epitope-specific T cells. Interestingly, unlike the generally diverse TCR repertoire of the anti-PyV CD8 T-cell response in B6 mice, the virus-specific Db-restricted T-cell response in CD8KO mice was typically comprised of cells expressing only a single TCR Vβ domain. In light of the importance of virus-specific CD8 T cells in protection against PyV tumorigenesis (5, 13, 26, 28), the ability of CD8KO mice to mount a virus-specific, MHC-I-restricted, T-cell response provides a possible explanation for the resistance of these mice to PyV-induced tumors.

Early studies were unable to detect MHC-I-restricted T-cell responses ex vivo against LCMV or VSV in CD8KO mice by using 51Cr release cytotoxicity assays (3, 14, 15). The low sensitivity of this assay generally fails to detect memory cytotoxic T cells in wild-type mice that are readily visualized by MHC-I tetramers and in vivo cytotoxicity assays (7). Additionally, given the delayed expansion of virus-specific MHC-I-restricted T cells in CD8KO mice (Fig. 1B), investigators in these previous studies (3, 14) may have assayed for LCMV-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) too early after infection. Low-level, alloreactive MHC-I-restricted responses in CD8KO mice have previously been described for a skin transplantation model (8). As in persistent viral infection, allogeneic skin grafts provide chronic antigenic stimulation that may help drive the expansion of the low number of naïve MHC-I-restricted T cells in CD8KO mice to detectable levels.

Despite variability among individual CD8KO mice in the size of PyV-specific, MHC-I-restricted, T-cell responses, these mice exhibited comparable efficiencies in controlling infection. Sera from infected B6 and CD8KO mice, irrespective of DbLT359 T-cell response levels, had similar titers of hemagglutination inhibition activity, indicating no differences in virus-neutralizing antibody levels (data not shown). PyV elicits both CD4 T-cell-dependent and -independent antiviral humoral responses, which, while promoting viral clearance, are not sufficient to prevent PyV tumorigenesis (1, 13, 27, 37, 38). We recently reported that MHC-II-deficient B6 mice, which maintain a small, chronic memory PyV-specific CD8 T-cell population, do not develop PyV-induced tumors (22); thus, even a small functional MHC-I-restricted T-cell response, as seen in the LR-CD8KO mice, would also likely be sufficient for PyV tumor resistance. Nevertheless, 20 to 30% of PyV-infected CD8KO mice have previously been reported to develop hind limb paralysis (13), which is associated with PyV-induced vertebral tumors (19, 41). Coincidentally, this frequency is similar to that of DbLT359-specific LR-CD8KO mice, raising the possibility that there may be some breakthrough tumors in the LR-CD8KO mice months after infection.

Previous work suggests that MHC-I-restricted T cells in CD8KO mice may compensate for the absence of CD8 by positively selecting thymocytes having high-affinity TCRs (18, 33). In support of this idea, CD8KO T cells bound DbLT359 tetramers more efficiently on a per-cell basis (Fig. 6A). However, these T cells did not exhibit greater sensitivity to Ag (Fig. 6C) or enhanced tetramer binding under conditions of limited ligand availability (Fig. 6B), two characteristics of high-avidity T cells (9, 11, 43). These data suggest that CD8-deficient, LT359-specific T cells do not possess higher-affinity TCRs. While the higher DbLT359 tetramer MFI in CD8KO mice cannot be explained by elevated TCR surface expression, the topological arrangement of TCRs has been shown to enhance MHC-I tetramer binding (12). Such compensatory mechanisms may be required to permit positive selection of MHC-I-restricted thymocytes in the absence of CD8.

The absence of CD8 coreceptor engagement may also be responsible for the depressed effector competence of virus-specific MHC-I-restricted T cells in the CD8KO mice. Stimulation with pMHC lacking the CD8 binding site results in incomplete TCR zeta-chain phosphorylation and only partial activation of T-cell effector functions (24, 32), and TCR signaling is handicapped by the absence of CD8-associated p56lck-mediated amplification (34). Similarly, during an infection by vaccinia virus or Listeria monocytogenes, the transient downregulation of CD8 results in decreased sensitivity to Ag (42). In our system, only approximately half of LT359-specific T cells from CD8KO animals were competent to produce IFN-γ (Fig. 3A). Although T-cell effector integrity is degraded in chronically infected hosts (16, 17, 25, 40), impaired IFN-γ production by CD8-deficient T cells was also seen after acute infection with rVSV-LT359 infection (data not shown). In vivo CTL assays showed that CD8-deficient T cells are less sensitive to low levels of cognate peptide during the acute phase of infection, a characteristic of low-avidity CTLs (13); a confounding variable, though, is that there were fewer DbLT359-specific T cells in CD8KO mice at this time point. In persistently infected CD8KO mice, however, T cells were much less efficient killers despite the presence of equivalent numbers of splenic LT359-specific T cells in B6 and CD8KO mice. The cytotoxicity effector apparatus appeared to be unaffected, as LT359-specific T cells in B6 and CD8KO mice had equivalent levels of granzyme B staining and abilities to mobilize CD107, a marker of degranulation (data not shown). Our data point toward an autonomous defect in TCR signaling by CD8-deficient virus-specific T cells.

A central finding was the profound oligoclonality of the MHC-I-restricted PyV-specific response in CD8KO mice. The availability of only a few clonotypes among naïve, anti-PyV, MHC-I-restricted T cells is a likely consequence of inefficient thymic selection for MHC-I-restricted thymocytes in the absence of CD8 (15). Without the contribution of the CD8 coreceptor, only a limited number of TCRs may possess sufficient affinity to transmit a positive selection signal. Stochastic selection of such a constrained repertoire of PyV epitope-reactive T-cell clonotypes would fit the mouse-to-mouse variability of Vβ expression profiles by antiviral MHC-I-restricted T cells in CD8KO mice. In support of this scenario, Jenkins and coworkers recently demonstrated that the Vβ expression profile of CD4 T cells that expand in response to a defined immunogen can be traced to that of the naïve Ag-specific CD4 T-cell population and, interestingly, that low frequencies of naïve epitope-specific CD4 T cells are associated with narrow and variable Vβ TCR expression profiles among individual mice (30). Moreover, small differences in numbers of naïve Ag-specific CD4 T cells were found to translate to marked differences in the size of the effector T-cell response. The observed variability in PyV-specific, MHC-I-restricted, T-cell responses among CD8KO mice may similarly reflect individual host differences in the number of antiviral naïve T cells. Another, not mutually exclusive, possibility is that the oligoclonality of MHC-I-restricted anti-PyV T cells in CD8KO mice may result from preferential expansion and maintenance of particular clonotypes during acute and persistent phases of PyV infection.

We recently demonstrated that naïve virus-specific CD8 T cells are continuously primed during persistent infection (21, 39). Ongoing recruitment, but drawing upon a limited number of naïve virus-specific T cells, may account for the delay in detecting DbLT359 tetramer+ T cells in CD8KO mice. As was seen in B6 mice, PyV-specific MHC-I-restricted T cells in CD8KO mice failed to proliferate and underwent progressive deletion when transferred to persistently infected recipients. Based on reduced virus-specific CD8 T-cell numbers in persistently infected thymectomized B6 mice, we proposed that resupply of the naïve T-cell compartment by recent thymic emigrants contributed to the maintenance of anti-PyV CD8 T cells during persistent infection (39). If thymic output were essential for the maintenance of chronic memory CD8 T cells in CD8KO mice, we would expect the marked oligoclonality of the PyV-specific T-cell population to diminish over time, as recent thymic emigrants expressing different Vβ TCRs were recruited into the preexisting MHC-I-restricted, antiviral T-cell pool. Yet, in CD8KO mice, MHC-I-restricted PyV-specific T cells retain a highly focused Vβ profile late into persistent infection. This finding raises the possibility that the trickle of MHC-I-restricted recent thymic emigrants in CD8KO mice, with the resulting small reserve of CD3+CD4− naïve T cells, might direct these hosts to rely on a self-renewing, extrathymic nonsplenic source to maintain chronic memory, MHC-I-restricted PyV-specific T cells. Alternatively, the naïve T-cell compartment in CD8KO mice may be populated with a sufficient number of PyV-specific MHC-I-restricted T cells, albeit clonotypically constrained, to permit ongoing de novo recruitment of antiviral T cells that also give rise to effector/memory T cells having a narrow Vβ expression profile.

Our description of MHC-I-restricted T-cell responses in CD8-deficient mice provides an explanation for the relative resistance to intracellular microbial infection of mice and humans lacking this T-cell coreceptor (10, 13). Moreover, the results of this study have practical implications for the use of CD8KO mice to investigate the contribution of MHC-I-restricted T-cell responses in tumor and infection models.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Public Health Service grants R01CA71971 and R01CA100644 (to A.E.L.) and, in part, by the University Research Committee of Emory University.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 12 March 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allison, A. C., and L. W. Law. 1968. Effects of antilymphocyte serum on virus oncogenesis. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 127207-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andrews, N. P., C. D. Pack, V. Vezys, G. N. Barber, and A. E. Lukacher. 2007. Early virus-associated bystander events affect the fitness of the CD8 T cell response to persistent virus infection. J. Immunol. 1787267-7275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bachmann, M. F., A. Oxenius, T. W. Mak, and R. M. Zinkernagel. 1995. T cell development in CD8−/− mice. Thymic positive selection is biased toward the helper phenotype. J. Immunol. 1553727-3733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bendig, M. M., T. Thomas, and W. R. Folk. 1980. Viable deletion mutant in the medium and large T-antigen-coding sequences of the polyoma virus genome. J. Virol. 331215-1220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berke, Z., T. Wen, G. Klein, and T. Dalianis. 1996. Polyoma tumor development in neonatally polyoma-virus-infected CD4−/− and CD8−/− single knockout and CD4−/−8−/− double knockout mice. Int. J. Cancer 67405-408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Busch, D. H., and E. G. Pamer. 1999. T cell affinity maturation by selective expansion during infection. J. Exp. Med. 189701-710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Byers, A. M., C. C. Kemball, J. M. Moser, and A. E. Lukacher. 2003. Cutting edge: rapid in vivo CTL activity by polyoma virus-specific effector and memory CD8+ T cells. J. Immunol. 17117-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dalloul, A. H., K. Ngo, and W. P. Fung-Leung. 1996. CD4-negative cytotoxic T cells with a T cell receptor alpha/beta intermediate expression in CD8-deficient mice. Eur. J. Immunol. 26213-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daniels, M. A., and S. C. Jameson. 2000. Critical role for CD8 in T cell receptor binding and activation by peptide/major histocompatibility complex multimers. J. Exp. Med. 191335-346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de la Calle-Martin, O., M. Hernandez, J. Ordi, N. Casamitjana, J. I. Arostegui, I. Caragol, M. Ferrando, M. Labrador, J. L. Rodriguez-Sanchez, and T. Espanol. 2001. Familial CD8 deficiency due to a mutation in the CD8α gene. J. Clin. Investig. 108117-123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Derby, M., M. Alexander-Miller, R. Tse, and J. Berzofsky. 2001. High-avidity CTL exploit two complementary mechanisms to provide better protection against viral infection than low-avidity CTL. J. Immunol. 1661690-1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drake, D. R., III, and T. J. Braciale. 2001. Cutting edge: lipid raft integrity affects the efficiency of MHC class I tetramer binding and cell surface TCR arrangement on CD8+ T cells. J. Immunol. 1667009-7013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drake, D. R., III, and A. E. Lukacher. 1998. β2-microglobulin knockout mice are highly susceptible to polyoma virus tumorigenesis. Virology 252275-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fung-Leung, W. P., T. M. Kundig, R. M. Zinkernagel, and T. W. Mak. 1991. Immune response against lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus infection in mice without CD8 expression. J. Exp. Med. 1741425-1429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fung-Leung, W. P., M. W. Schilham, A. Rahemtulla, T. M. Kundig, M. Vollenweider, J. Potter, W. van Ewijk, and T. W. Mak. 1991. CD8 is needed for development of cytotoxic T cells but not helper T cells. Cell 65443-449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gillespie, G. M., M. R. Wills, V. Appay, C. O'Callaghan, M. Murphy, N. Smith, P. Sissons, S. Rowland-Jones, J. I. Bell, and P. A. Moss. 2000. Functional heterogeneity and high frequencies of cytomegalovirus-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes in healthy seropositive donors. J. Virol. 748140-8150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goepfert, P. A., A. Bansal, B. H. Edwards, G. D. Ritter, Jr., I. Tellez, S. A. McPherson, S. Sabbaj, and M. J. Mulligan. 2000. A significant number of human immunodeficiency virus epitope-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes detected by tetramer binding do not produce gamma interferon. J. Virol. 7410249-10255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goldrath, A. W., K. A. Hogquist, and M. J. Bevan. 1997. CD8 lineage commitment in the absence of CD8. Immunity 6633-642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harper, J. S., III, C. J. Dawe, B. D. Trapp, P. E. McKeever, M. Collins, J. L. Woyciechowska, D. L. Madden, and J. L. Sever. 1983. Paralysis in nude mice caused by polyomavirus-induced vertebral tumors. Prog. Clin. Biol. Res. 105359-367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holler, P. D., and D. M. Kranz. 2003. Quantitative analysis of the contribution of TCR/pepMHC affinity and CD8 to T cell activation. Immunity 18255-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kemball, C. C., E. D. Lee, V. Vezys, T. C. Pearson, C. P. Larsen, and A. E. Lukacher. 2005. Late priming and variability of epitope-specific CD8+ T cell responses during a persistent virus infection. J. Immunol. 1747950-7960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kemball, C. C., C. D. Pack, H. M. Guay, Z. N. Li, D. A. Steinhauer, E. Szomolanyi-Tsuda, and A. E. Lukacher. 2007. The antiviral CD8+ T cell response is differentially dependent on CD4+ T cell help over the course of persistent infection. J. Immunol. 1791113-1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kerry, S. E., J. Buslepp, L. A. Cramer, R. Maile, L. L. Hensley, A. I. Nielsen, P. Kavathas, B. J. Vilen, E. J. Collins, and J. A. Frelinger. 2003. Interplay between TCR affinity and necessity of coreceptor ligation: high-affinity peptide-MHC/TCR interaction overcomes lack of CD8 engagement. J. Immunol. 1714493-4503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laugel, B., D. A. Price, A. Milicic, and A. K. Sewell. 2007. CD8 exerts differential effects on the deployment of cytotoxic T lymphocyte effector functions. Eur. J. Immunol. 37905-913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee, P. P., C. Yee, P. A. Savage, L. Fong, D. Brockstedt, J. S. Weber, D. Johnson, S. Swetter, J. Thompson, P. D. Greenberg, M. Roederer, and M. M. Davis. 1999. Characterization of circulating T cells specific for tumor-associated antigens in melanoma patients. Nat. Med. 5677-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liunggren, G., H. G. Liunggren, and T. Dalianis. 1994. T cell subsets involved in immunity against polyoma virus-induced tumors. Virology 198714-716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lukacher, A. E., R. Freund, J. P. Carroll, R. T. Bronson, and T. L. Benjamin. 1993. Pyvs: a dominantly acting gene in C3H/BiDa mice conferring susceptibility to tumor induction by polyoma virus. Virology 196241-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lukacher, A. E., and C. S. Wilson. 1998. Resistance to polyoma virus-induced tumors correlates with CTL recognition of an immunodominant H-2Dk-restricted epitope in the middle T protein. J. Immunol. 1601724-1734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martínez, C., M. A. Marcos, I. M. de Alboran, J. M. Alonso, R. de Cid, G. Kroemer, and A. Coutinho. 1993. Functional double-negative T cells in the periphery express T cell receptor Vβ gene products that cause deletion of single-positive T cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 23250-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moon, J. J., H. H. Chu, M. Pepper, S. J. McSorley, S. C. Jameson, R. M. Kedl, and M. K. Jenkins. 2007. Naive CD4+ T cell frequency varies for different epitopes and predicts repertoire diversity and response magnitude. Immunity 27203-213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murali-Krishna, K., J. D. Altman, M. Suresh, D. J. Sourdive, A. J. Zajac, J. D. Miller, J. Slansky, and R. Ahmed. 1998. Counting antigen-specific CD8 T cells: a reevaluation of bystander activation during viral infection. Immunity 8177-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Purbhoo, M. A., J. M. Boulter, D. A. Price, A. L. Vuidepot, C. S. Hourigan, P. R. Dunbar, K. Olson, S. J. Dawson, R. E. Phillips, B. K. Jakobsen, J. I. Bell, and A. K. Sewell. 2001. The human CD8 coreceptor effects cytotoxic T cell activation and antigen sensitivity primarily by mediating complete phosphorylation of the T cell receptor ζ chain. J. Biol. Chem. 27632786-32792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sebzda, E., M. Choi, W. P. Fung-Leung, T. W. Mak, and P. S. Ohashi. 1997. Peptide-induced positive selection of TCR transgenic thymocytes in a coreceptor-independent manner. Immunity 6643-653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Slifka, M. K., and J. L. Whitton. 2001. Functional avidity maturation of CD8+ T cells without selection of higher affinity TCR. Nat. Immunol. 2711-717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sullivan, Y. B., A. L. Landay, J. A. Zack, S. G. Kitchen, and L. Al-Harthi. 2001. Upregulation of CD4 on CD8+ T cells: CD4dimCD8bright T cells constitute an activated phenotype of CD8+ T cells. Immunology 103270-280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sykes, M. 1990. Unusual T cell populations in adult murine bone marrow. Prevalence of CD3+CD4−CD8− and αβTCR+NK1.1+ cells. J. Immunol. 1453209-3215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Szomolanyi-Tsuda, E., and R. M. Welsh. 1996. T cell-independent antibody-mediated clearance of polyoma virus in T cell-deficient mice. J. Exp. Med. 183403-411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vandeputte, M. 1968. The effect of heterologous antilymphocytic serum on the oncogenic activity of polyoma virus. Life Sci. 7855-865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vezys, V., D. Masopust, C. C. Kemball, D. L. Barber, L. A. O'Mara, C. P. Larsen, T. C. Pearson, R. Ahmed, and A. E. Lukacher. 2006. Continuous recruitment of naive T cells contributes to heterogeneity of antiviral CD8 T cells during persistent infection. J. Exp. Med. 2032263-2269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wherry, E. J., J. N. Blattman, K. Murali-Krishna, R. van der Most, and R. Ahmed. 2003. Viral persistence alters CD8 T-cell immunodominance and tissue distribution and results in distinct stages of functional impairment. J. Virol. 774911-4927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wirth, J. J., A. Amalfitano, R. Gross, M. B. Oldstone, and M. M. Fluck. 1992. Organ- and age-specific replication of polyomavirus in mice. J. Virol. 663278-3286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xiao, Z., M. F. Mescher, and S. C. Jameson. 2007. Detuning CD8 T cells: down-regulation of CD8 expression, tetramer binding, and response during CTL activation. J. Exp. Med. 2042667-2677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yee, C., P. A. Savage, P. P. Lee, M. M. Davis, and P. D. Greenberg. 1999. Isolation of high avidity melanoma-reactive CTL from heterogeneous populations using peptide-MHC tetramers. J. Immunol. 1622227-2234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]