Abstract

Binge drinking and non-daily cigarette smoking are behaviors that are both problematic and prevalent in young adults. Although the relationship between drinking and daily smoking has been well categorized, the intersection between drinking and smoking in non-daily smokers has not been heavily researched. Past 30-day and within-episode patterns of alcohol and cigarette use were collected in young adult non-daily smokers (N = 40). Results demonstrated that 79% of smoking occurred on drinking days. Alcohol use was significantly greater on smoking days with the result that drinking to risky binge levels was more likely to occur on a smoking day. Smoking typically occurred after a certain level of alcohol pre-load (2.87 drinks). Together these results confirm that young adult non-daily smokers often concurrently use alcohol and cigarettes. Research is needed to identify possible mechanisms underlying the association between binge drinking and cigarette use in this vulnerable population.

Keywords: Binge drinking, Alcohol, Smoking, Tobacco, Young Adults

1. Introduction

Heavy episodic drinking (i.e., binge drinking) is defined as consuming five or more drinks per episode for males, and four or more drinks per episode for females (USDHHS, 2005; SAMSHA, 2005). Binge drinking is a major public health problem in the U.S. (Dawson, Grant, Stinson, & Chou, 2004; Wechsler & Kuo, 2000; Task Force on College Drinking, 2002), and despite significant public health measures, rates of binge drinking have risen almost 20% in young adults since 1993 (Naimi, Brewer, Mokdad, Denny, Serdula, & Marks, 2003; Wechsler, Lee, Kuo, Seibring, Nelson, & Lee, 2002). The period of highest risk is evidenced in young adults (21–24 years; Naimi et al., 2003; USDHHS, 2002), with 44% reporting past year binge drinking, and 14% reporting at least weekly binge drinking (Dawson et al., 2004). This consumption pattern is associated with serious adverse consequences including the development of alcohol use disorders, unintentional injuries, property damage, assault, car crashes, unprotected sex, alcohol poisoning, and death (e.g., Wechsler, Davenport, Dowdall, Moeykens, & Castillo, 1994; Wechsler, et al., 2002; Naimi et al., 2003; NHTSA, 2004; Rossow, 1996).

Smoking is also a major health problem in young adults. Prevalence estimates find that 30% of college students are current smokers (Everett, Husten, Kann, Warren, Sharp, & Crosset, 1999; Johnston, O’Malley, & Bachman, 1999; 2001; Rigotti, Lee, & Wechsler, 2000). Data from the 2004 National Health Interview survey shows that 23.6% adults aged 18–24 were current smokers, compared to 20.9% of the entire population (CDC, 2005). With regard to non-daily smoking, population studies have documented that 19%–24% of current smokers are non-daily smokers (Hassmiller, Warner, Mendez, Levy, & Romano, 2003; Hennrikus, Jeffery, & Lando, 1996), with younger age being significantly associated with this smoking pattern (Gilpin, Cavin, & Pierce, 1997; Hassmiller et al., 2003; Hennrikus et al., 1996).

Binge drinking is highly co-morbid with daily and non-daily smoking behavior (Bobo & Husten, 2000; McKee, Hinson, Rounsaville, & Petrelli, 2004; Schorling, Gutgesell, Klas, Smith, & Keller, 1994; Weitzmann & Chen, 2005). NIAAA-defined hazardous drinking, which is primarily characterized by past year binge drinking (USDHHS, 2005), was found to be 3 times more likely among daily smokers, and 5 times more likely among non-daily smokers compared to never-smokers, using the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions data (McKee, Falba, O’Malley, Sindelar, & O’Connor, 2007). Studies of adolescents and young adults find that past month binge drinkers were 5 times more likely to be smokers (Bobo & Husten, 2000). Both non-daily and daily smokers were 4 times more likely than non-smokers to report binge drinking (Schorling et al., 1994), and 44% of current smokers engaged in binge drinking at least once per month (Weitzmann & Chen, 2005).

For the current study, we were interested in the association between non-daily smoking and alcohol use. Despite ample epidemiological evidence that binge drinking and non-daily smoking co-occur, little information regarding episodic alcohol and cigarette use has been reported. Non-daily smoking is of public health significance given its relationship with hazardous alcohol use and also because those individuals who engage in this smoking pattern may progress to daily smoking (Chassin et al., 2000). Moreover, a greater understanding of how non-daily smokers use alcohol and cigarettes could assist in the development of new prevention and intervention measures for hazardous alcohol use. We collected survey and interview data in a community sample of young adult non-daily smokers (age 21–25) to highlight episodic smoking and drinking behavior in this population. Participants reported past 30 day and within-episode patterns of concurrent alcohol and cigarette use.

2. Method

2.1 Participants

Forty volunteers participated in this study (43% female). All volunteers provided informed consent for their participation. Entrance criteria included drinking alcohol at least two days a week and smoking cigarettes at least once a month. Volunteers were not daily smokers and had no history of daily smoking. The Structured Clinical Interview (DSM-IV; First et al., 1997) was used to exclude those presenting with nicotine or alcohol dependence. All volunteers were 21–25 years old to focus on young adults of legal drinking age. The mean age was 22.05 (SD = 1.10). Volunteers were primarily Caucasian (82.5%), with 10% African American, 2.5% Korean, 2.5% Vietnamese, and 2.5% reporting other. Regarding marital status, most were single (92.5%), 2.5% reported being separated, and 5% were cohabitating. Most volunteers had completed either some college or college (85%), with 5% reporting high school degree and 7.5% reporting some post-college work. Current college students comprised 60% of the sample.

2.2 Procedure

Participants completed a single 1 hour session involving interview and self-report assessments.

2.3 Tobacco and Alcohol Use

Participants were asked to self-report past year frequency and quantity of cigarette and alcohol use. The 6-item Fagerström Test of Nicotine Dependence (Heatherton, Kozlowski, Frecker, & Fagerström, 1991) was used to assess nicotine dependence (range 1–10). The 10-item Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT; Saunders, Aasland, Babor, de la Fuente, & Grant, 1993) was used to assess alcohol use disorders (range 0–40; scores of 8 or greater indicated problematic drinking).

2.4 30 Days Timeline Followback Alcohol and Cigarette Use

Quantity and frequency information of volunteers’ alcohol consumption and cigarette smoking for the 30-day period prior to the study (Sobell & Sobell, 1993) was collected. Volunteers were presented with a calendar for the 30-day period and were asked to report how many drinks they consumed and how many cigarettes they smoked on each day.

2.5 Typical Within-Episode Alcohol and Cigarette Use

Participants estimated what percentage of their smoking episodes occurred while under the influence of alcohol. Participants were asked to “think about a typical drinking episode in which you smoked cigarettes”. Participants self-reported their typical alcohol and cigarette consumption during a typical use episode (Harrison, Hinson, & McKee, under review). They were asked to report, by hour, for up to an 8-hour period, how many alcohol drinks they would typically consume and how many cigarettes they would typically smoke. “For each hour during a typical drinking episode, we would like you to record how many standard drinks and cigarettes you had within that 1 hour period”. A standard drink was defined as “12 oz bottle of beer, or 1.5 oz of liquor, or 5 oz wine”.

3. Results

3.1 Baseline Smoking and Alcohol Use

Participants smoked an average of 8.18 (SD = 5.44) times per month with 2.57 (SD = 1.59) cigarettes per smoking day. They drank an average of 14.74 (SD = 10.28) alcoholic drinks per week, drank an average of 2.60 (SD = 0.87) times per week, and engaged in binge drinking 1.54 (SD = 1.02) times per week. Binge drinking was defined as consuming five or more drinks per episode for males and four or more drinks per episode for females (USDHHS, 2005; SAMSHA, 2005). 59% of drinking days met criteria for binge drinking. The mean FTND score was 0.2 (SD = 0.61), indicating an absence of nicotine dependence. The mean AUDIT score was 9.78 (SD = 4.05), indicating problematic alcohol consumption.

3.2 30 Days Timeline Followback Alcohol and Cigarette Use

Using the 30-day timeline data, we found that 79% of all smoking occurred on days that also involved alcohol use. Non-daily smokers consumed significantly more drinks on days that smoking occurred than on days when smoking did not occur, t(39) = 6.46, p < .001. The mean number of drinks on a smoking day was 5.80 (SD = 4.82) and 1.09 (SD = 1.30) drinks on a non-smoking day, suggesting that smoking was associated with binge drinking. Non-daily smokers smoked significantly more cigarettes during binge drinking episodes than during non-binge drinking episodes, t(30) = 4.13, p < .001. They smoked an average of 2.13 (SD = 2.26) cigarettes during binge drinking episodes, compared to 0.89 (SD = 0.99) cigarettes during non-binge drinking episodes.

3.3 Episodic Smoking and Drinking

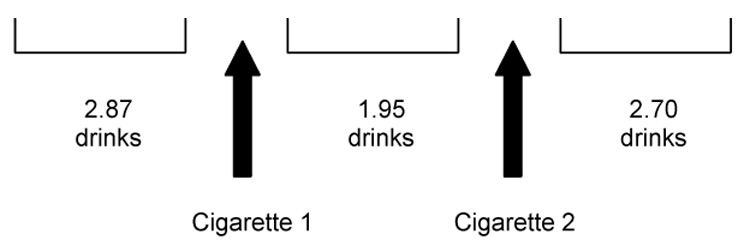

Using the hour-by-hour timeline of a typical smoking and drinking episode, volunteers reported that they consumed 7.5 (SD = 3.62) drinks and 3.35 (SD = 2.49) cigarettes over the course of 5.15 hours. The majority of participants started smoking by the second hour of drinking after consuming 2.87 (SD=3.05) drinks, suggesting that smoking occurred after a certain level of alcohol pre-load in these young adult non-daily smokers. Figure 1 illustrates that after participants smoked their first cigarette, they consumed an additional 4.63 (SD = 2.99) drinks, with 2.5 (SD = 1.52) uses of (primarily) single cigarettes spaced throughout the drinking episode.

Figure 1.

Sequencing of within-episode drinking and smoking in young adult non-daily smokers.

4. Discussion

Although the relationship between drinking and daily smoking has been well categorized (e.g., Istvan & Matarazzo, 1984; Bien & Burge, 1990), the intersection between drinking and smoking in non-daily smokers has not been heavily researched. Recent findings from National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions indicate that non-daily smokers have higher rates of binge drinking, in comparison to never smokers, than do daily smokers (McKee et al., 2007). The purpose of this study was to describe daily and episodic patterns of drinking and cigarette smoking in this population. Non-daily smokers consumed more drinks on smoking days, with the result that they were more likely to drink to risky binge levels on these days in comparison to non-smoking days. They were also more likely to report smoking on drinking days, and particularly on binge drinking days, than on non-drinking days. Increased cigarette smoking was reported on binge drinking days. Lastly, volunteers reported that they typically consumed 2–3 drinks before initiating smoking, suggesting that they often consume an alcohol pre-load before smoking. Together these findings provide evidence that young adult non-daily smokers frequently choose to combine drinking alcohol and smoking cigarettes and concurrent use potentiated levels of use for each substance.

The mechanisms supporting the strong association between binge drinking and non-daily smoking in young adult non-daily smokers remain unclear. Nicotine has been observed to increase alcohol consumption in occasional, non-dependent male smokers (Barrett, Tichauer, Leyton, & Pihl, 2006). The within-episode reports in the present study support this observation that cigarette smoking can increase alcohol use. Other research has indicated that the relationship between alcohol use and cigarette smoking is more reciprocal in nature, with each drug increasing the reinforcing properties of the other (e.g., Rose, Brauer, Behm, Cramblett, Calkins, & Lawhon, 2004). The present findings, specifically that more drinks were consumed on drinking days and more smoking days were drinking days, supports this approach. Future research is necessary to clarify this association in order to understand why young adult non-daily smokers so often drink to binge levels while smoking cigarettes.

Possible limitations of the study include the use of self-reports of alcohol and cigarette use. Past research has indicated that these measures are reliable (Sher & Epler, 2004). Although reports of daily drinking and smoking behaviors might be reliable, the reliability and validity of the interview regarding episodic behavior is not known. Another possible limitation is that the present study reports on a small sample, which might not necessarily represent young adult non-daily smokers on a national level. Participants were recruited from the community regardless of current college enrollment, thus allowing a representation of all young adult non-daily smokers aged 21–25. As indicated by epidemiological data, this population comprises a large percentage of young adults. Future studies using a wider age range, such as non-daily smokers aged 18–25 years, and a greater sample size could provide additional information regarding the alcohol and cigarette use patterns of this population.

In examining the actual patterns of alcohol drinking and cigarette smoking in young adult non-daily smokers it is apparent that more information is needed in order to create more effective prevention and treatment options. The strong relationship between non-daily smoking and binge drinking indicates that non-daily smoking is of considerable public health concern. Future studies are needed to identify possible mechanisms underlying the association between binge drinking and cigarette smoking in this vulnerable population. Limiting the availability of smoking areas in drinking establishments, such as through smoking bans, could potentially have the beneficial effect of decreasing binge drinking rates.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Alcoholic Beverage Medical Research Foundation (McKee) and by the National Institute on Alcohol and Alcoholism (P50AA15632).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett SP, Tichauer M, Leyton M, Pihl RO. Nicotine increases alcohol self-administration in non-dependent male smokers. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;81:197–204. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bien TH, Burge J. Smoking and drinking: a review of the literature. International Journal of the Addictions. 1990;25:1429–1454. doi: 10.3109/10826089009056229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobo JK, Husten C. Socio-cultural influences on smoking and drinking. Alcohol & Health Research. 2000;24:225–232. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cigarette smoking among adults – United States 2004. Morbidity and Mortality Report. 2005;54:1121–1124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Presson CC, Pitts SC, Sherman SJ. The natural history of cigarette smoking from adolescence to adulthood in a Midwestern community sample: multiple trajectories and their psychosocial correlates. Health Psychology. 2000;19:223–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Grant BF, Stinson FS, Chou PS. Another look at heavy episodic drinking and alcohol use disorders among college and noncollege youth. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65:477–488. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everett S, Husten C, Kann L, Warren C, Sharp D, Crosset L. Smoking initiation and smoking patterns among US college students. Journal of American College Health. 1999;48:55–60. doi: 10.1080/07448489909595674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Gilpin E, Cavin SW, Pierce JP. Adult smokers who do not smoke daily. Addiction. 1997;92(4):473–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison ELR, Hinson RE, McKee SA. Episodic patterns of alcohol and cigarette use in experimenters and smokers. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.12.013. (under review) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassmiller KM, Warner KE, Mendez D, Levy DT, Romano E. Nondaily smokers: who are they? American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(8):1321–1327. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.8.1321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerström K. The Fagerström Test for nicotine dependence: a revision of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. British Journal of Addiction. 1991;86:1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennrikus DJ, Jeffery RW, Lando HA. Occasional smoking in a Minnesota working population. American Journal of Public Health. 1996;86(9):1260–1266. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.9.1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Istvan J, Matarazzo JD. Tobacco, alcohol, and caffeine use: a review of their relationships. Psychological Bulletin. 1984;95:301–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson KM, Sher KJ, Wood PK. Prospective analysis of comorbidity: tobacco and alcohol use disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2000;109:679–694. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.109.4.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG. Washington, DC: US Dept of Health and Human Services; National Survey Results on Drug Use from the Monitoring the Future Study 1975–1998; Volume 2, College Students and Young Adults. 1999 NIH publication 99-4661.

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; Monitoring the future: National survey results on drug use, Volume II: College students and adults ages 19–40. 2001 (NIH Publication No 01-4925)

- McKee SA, Falba T, O’Malley SS, Sindelar J, O’Connor PG. Smoking status is a clinical indicator for alcohol misuse in US adults. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2007;167:716–721. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.7.716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee SA, Hinson R, Rounsaville D, Petrelli P. Survey of subjective effects of smoking while drinking among college students. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2004;6:111–117. doi: 10.1080/14622200310001656939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naimi TS, Brewer RD, Mokdad A, Denny C, Serdula MK, Marks JS. Binge drinking among US adults. JAMA. 2003;289:70–75. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) Washington, DC: US Department of Transportation; Traffic Safety Facts 2003 Annual Report: Early Edition. 2004

- Rigotti NA, Lee JE, Wechsler H. US college students’ use of tobacco products: Results of a national survey. Journal of the American Medication Association. 2000;284:699–705. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.6.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose JE, Brauer LH, Behm FM, Cramblett M, Calkins K, Lawhon D. Psychopharmacological interactions between nicotine and ethanol. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2004;6:133–144. doi: 10.1080/14622200310001656957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossow I. Alcohol-related violence: the impact of drinking pattern and drinking context. Addiction. 1996;91:1651–1661. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1996.911116516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA. Bethesda, MD: National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Office of Applied Studies. 2005

- Saunders JB, Asland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT). WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption. II. Addiction. 1993;88:791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schorling JB, Gutgesell M, Klas P, Smith D, Keller A. Tobacco, alcohol and other drug use among college students. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1994;16:105–115. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(94)90143-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Epler A. Alcoholic denial: self-awareness and beyond. In: Beitman B, Nair J, editors. Self awareness deficits in psychiatric patients: neurobiology, assessment, and treatment. New York: W.W. Norton and Company; 2004. pp. 184–212. [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline Followback: A technique for assessing self-reported ethanol consumption. In: Allen J, Litten R, editors. Techniques to assess alcohol consumption. New Jersey: Humana Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Task Force on College Drinking. High-Risk Drinking in College: What We Know and What We Need to Learn. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; Results from the 2001 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Volume I. Summary of National Findings (Office of Applied Studies, NHSDA Series H-17 ed.) (BKD461, SMA 02-3758) 2002

- US Department of Health and Human Services. [Accessed May 25, 2006];Helping Patients Who Drink Too Much: A clinician’s guide. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. 2005 Available at: http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/Practitioner/CliniciansGuide2005/guide.pdf.

- Wechsler H, Davenport A, Dowdall G, Moeykens B, Castillo S. Health and behavioral consequences of binge drinking in college: a national survey of students at 140 campuses. JAMA. 1994;272:1672–1677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Kuo M. College students define binge drinking and estimate its prevalence: results of a national survey. Journal of American College Health. 2000;49:57–64. doi: 10.1080/07448480009596285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Lee JE, Kuo M, Seibring M, Nelson TF, Lee H. Trends in college binge drinking during a period of increased prevention efforts. Journal of American College Health. 2002;50:203–217. doi: 10.1080/07448480209595713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitzman ER, Chen Y. The co-occurrence of smoking and drinking among young adults in college: National survey results from the United States. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2005;80:377–386. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]