Abstract

The ability to tolerate a low-O2 environment varies widely among species in the animal kingdom. Some animals, such as Drosophila melanogaster, can tolerate anoxia for prolonged periods without apparent tissue injury. To determine the genetic basis of the cellular responses to low O2, we performed a genetic screen in Drosophila to identify loci that are responsible for anoxia resistance. Four X-linked, anoxia-sensitive mutants belonging to three complementation groups were isolated after screening more than 10,000 mutagenized flies. The identified recessive and dominant mutations showed marked delay in recovery from O2 deprivation. In addition, electrophysiologic studies demonstrated that polysynaptic transmission in the central nervous system of the mutant flies was abnormally long during recovery from anoxia. These studies show that anoxic tolerance can be genetically dissected.

Each year millions of individuals in the United States die or become morbidly ill because of conditions or diseases that acutely reduce O2 supply to hypoxia-sensitive tissues, such as the myocardium, central nervous system, and kidneys. Over the past several decades, most research has focused on mechanisms of vessel disease (e.g., atherosclerosis) that lead to stroke or myocardial infarction and on their prevention. However, little is known about the molecular mechanisms underlying the cellular responses to lack of oxygenation and how to prevent damage once a reduction in O2 supply has occurred.

The study of cell responses to low O2 is important not only for understanding disease mechanisms but also for understanding normal biologic processes. Recent observations have shown, for example, that O2 deprivation can have profound effects on cell proliferation, differentiation, and tumor growth via its effect on cell-cycle check points, including cyclins and proteins such as bcl2 and p53 (1–4). When faced with a complete lack of O2 (anoxia), shrimp (5) and Drosophila (6) embryos stop growing and enter a phase of total developmental arrest that is relieved only with the reintroduction of O2. Development can resume even after 2 years of anoxia (6).

Different phyla and species have various responses to lack of O2 (7). Even different organs and different cell types within the same organ (e.g., CA1 and dentate cells in the hippocampus) can have marked differences in anoxia tolerance, ranging from extreme tolerance to high vulnerability. Although there are data describing the changes that occur in cells, especially nerve cells, of mammalian and nonmammalian species in response to a low O2 environment (7, 8–11), the genetic basis for the cellular responses to low O2 has not been elucidated.

We have recently shown that the wild-type Drosophila melanogaster [Canton-S (C-S)] is extremely resistant to anoxia (12). This fruit fly, with an O2 consumption rate that exceeds even mammalian levels and a total life span of several weeks, can survive hours in anoxia and, apparently, not suffer tissue injury. Thus, we have taken advantage of this model system to study the genetic basis of anoxia tolerance.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Anoxia Testing.

A specially designed chamber was used to study flies under controlled O2 and temperature conditions (Fig. 1A). Groups of 20–25 adult flies, ages 3–6 days, were placed in the chamber and exposed to anoxic conditions (O2 concentration = 0% with administration of 100% N2) for 5 min before allowing recovery in room air (O2 = 20.8%). Although Drosophila can survive for a much longer period under very low O2 conditions, a short period of anoxia of only 5 min was chosen because: (i) mutants defective in protective responses may not survive prolonged periods and (ii) screening a large number of flies becomes too impractical if the test time is long. After the introduction of N2 in the chamber, flies became uncoordinated within 25–30 sec, fell to the bottom of the container, stopped moving, and stayed motionless for the rest of the anoxia period. This time (25–30 sec) was deemed to be too short to use in a screen. After 2–3 min of reoxygenation, flies first exhibited rhythmic movements of the distal parts of their legs; this was followed by an abrupt and discrete change from a side or back position to a prone position with purposeful movements such as walking. The time for each fly to reach arousal, starting with reoxygenation, was referred to as recovery time. This time (tr in Fig. 1B) was deemed to be more suitable for a screen and therefore was utilized for all flies.

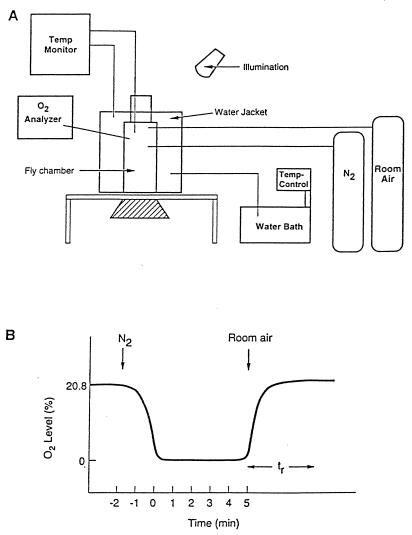

Figure 1.

(A) Specially designed testing chamber for adult Drosophila flies. The fly chamber (volume, 275 ml) is surrounded by a jacket through which temperature-controlled water (25°C) circulates from a water bath. Temperature and O2 are continuously measured in the fly chamber. Illumination is used to attract flies to the top of the chamber. Flies are introduced in the chamber from a top opening. The hatched container is a removable part used for fly collection. (B) Schematic diagram showing both the quick descent and ascent in O2 concentration in the fly chamber, both of which occurred within 2 min. With the administration of N2, flies lose coordination, fall onto the floor of the chamber (at O2 = 2.5%), and become motionless until room air (O2 = 20.8%) is re-admitted. The 5-min period of anoxia is measured starting from when O2 concentration reaches 0.9%. tr, or recovery time, usually is more than 3.5 min, with a mean of about 5.5 min in wild-type flies.

Genetic Screen for Anoxia-Sensitive Mutants.

We focused our screen for mutations on the X chromosome, because the mutant phenotype can be observed in the immediate next generation without the need for single-pair matings. Mutagenized (x-ray, 4,000 rad) C-S males, which were crossed to attached-X females [c(1)ywf], transmitted their mutagenized X chromosome to the male offspring. Suspected mutants were mated again to attached X females, and their progeny were retested to confirm the transmissibility of the phenotype and ascertain the identity of the inheritance pattern.

Genetic Mapping.

Mapping of the induced mutations was performed with X chromosomal markers and complementation tests. Several markers were used, including y, cv, v, f, car, and su(f). Complementation testing was done on the three X-linked recessive mutations obtained.

Central Nervous System Stimulation.

Because the giant fiber (GF) system has been well studied (13, 14), we made use of it to examine mutant and wild-type flies. Unanesthetized flies were placed on a microscope stage in the prone position with the help of soft wax. Stimulating electrodes were placed through the eye into the brain, and ground electrodes were placed in the abdomen. Dorsal longitudinal muscle (DLM)-recording electrodes were inserted in the thorax medial to the anterior dorsocentral bristles. Latency was measured with an oscilloscope (Tektronix 5111) and was defined as the period from the end of the stimulus artifact to the beginning of the voltage deflection of the evoked response. Low-voltage pulses to the brain gave rise to long latency responses (on the order of 4 msec) when recording from the DLM. With increasing stimulus strength, shorter latencies were obtained, reaching a minimum of 1.3 msec at the DLM. The shortest latency responses were shown to be the result of the direct stimulation of the GF neuronal system (15).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Anoxic Response of Wild-Type Flies and Isolation of Anoxia-Sensitive Mutants.

To find optimal conditions for the isolation of anoxia-sensitive mutants, we first studied the wild-type (C-S) response to anoxia. Fig. 2 A and D shows the wild-type male and female recovery times. The recovery time distribution for males had a relatively narrow spread around a mean of 331 sec (SD = ±61.1 sec; n = 91), and the female distribution (n = 77) was similar to that of the male, with an average of 314 ± 52.5 sec. Recovery time was reproducible not only for fly populations but also for individual flies because the same flies tested repeatedly and individually (e.g., consecutive days) had very similar recovery times. This tight spread of the wild-type distribution (Fig. 2A) and repeatability of recovery times provided an excellent opportunity to detect individual mutant flies that deviated from the normal.

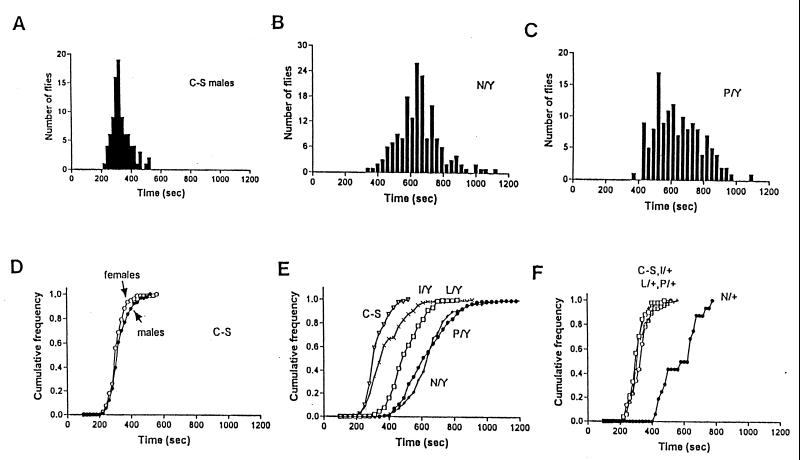

Figure 2.

Distribution and cumulative frequency of recovery times for wild-type (C-S) and mutant flies. The Hypnos-1N, hypnos-2P,L, and hypnos-3I mutants are abbreviated by N, P, L, or I on the plots. Y is used to indicate Y chromosome in males. (A–C) Distributions of the wild-type and the two more severe mutant male populations. Note the major difference in their distributions with almost complete lack of overlap between the wild-type and mutant populations. Female flies heterozygous for mutations hypnos-2L,P and hypnos-3I have a phenotype similar to that of wild-type flies (D–F). In F, the phenotype of Hypnos-1N heterozygotes is also shown.

A total of 10,818 flies, carrying mutagenized chromosomes, were screened. A threshold of 480 sec, which is close to the 96th percentile of the wild-type distribution, was used to identify and isolate mutants. Six mutations, four of which were X-linked, were identified and found to alter profoundly the distribution of recovery times. The marked delay in recovery after anoxia displayed by these mutant flies suggested that they were much more sensitive to a lack of O2. We therefore have termed these mutants hypnos to describe (i) sensitivity to O2 deprivation (hypoxia, anoxia, sensitive) and (ii) the phenotype of delayed recovery and “sleepiness,” because Hypnos is the personification of sleep in Greek mythology.

Fig. 2 B and C shows the recovery time distributions of male flies with the X chromosome mutations hypnos-1Nand hypnos-2P, respectively. The distribution of their recovery times has little overlap with and is wider than the C-S distribution. For both mutants, the average fly takes twice as long to recover as the wild-type fly (means ± SD = 653.4 ± 134.8 and 644 ± 147.2 sec). The other two mutations have less severe phenotypes and their means ± SD are 509 ± 100 (hypnos-2L) and 390 ± 118.2 sec (hypnos-3I). The cumulative frequency of recovery times for each of the four X chromosomal mutant flies is shown in Fig. 2E along with the wild-type response for comparison. Three of the mutations are recessive, because the heterozygote females have recovery distributions similar to those of the wild type. The mutant hypnos-1N has a dominant effect, because the heterozygote females have a recovery time close to that in the males with this mutation (Fig. 2 D and E).

The delay in recovery from anoxia in these mutants appears to have resulted from an enhanced sensitivity to low O2, because these mutants also lose motor control faster than wild-type flies when exposed to anoxia. C-S flies start to lose control at an O2 concentration of 2.5–3% during anoxia induction, but the mutant ones are affected at a concentration of about 5% when the same N2 flow rate is used.

Mutation Mapping.

Fig. 3 shows the cumulative distribution of recovery times for the three recessive mutations in females. The heterozygote females (hypnos/+; Fig. 3A) have a distribution similar to C-S males or females (see above). However, transheterozygotes of hypnos-2P and hypnos-2L have a very abnormal distribution with a mean ± SD of 621 ± 238 sec, suggesting that they belong to the same locus. In contrast, Fig. 3B shows that the third mutation (hypnos-3I) complements both hypnos-2P and hypnos-2L. Results of genetic mapping using multiply marked chromosomes [y, cv, v, f, car, su(f)] are consistent with these complementation tests. Both hypnos-2P and hypnos-2L have been mapped to the region between y and cv, whereas hypnos-3I is between v and f. The dominant mutation (Hypnos-1N) has also been mapped and is located distal to f. These data show that the X-linked mutants belong to three different loci.

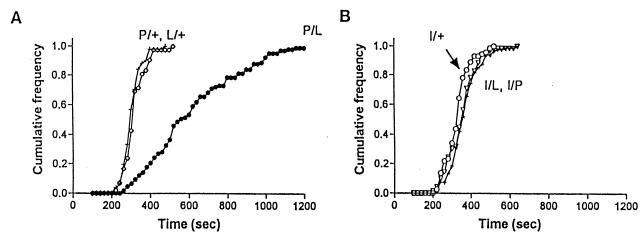

Figure 3.

Cumulative frequency of recovery times for heterozygote and transheterozygote females. The hypnos-2P/hypnos-2L transheterozygote females (P/L) had very delayed recovery times (A), whereas double heterozygotes between mutations hypnos-3 and hypnos-2 complemented each other (B).

hypnos Mutations Affect Central Nervous System Recovery from Anoxia.

The behavioral testing, which showed delayed recovery from anoxia, led us to believe that the hypnos mutations affected the central nervous system. To further our understanding of the mutations we obtained, we directly examined the effect of these mutations on central nervous system function. The only identified neurons that can be studied electrophysiologically in Drosophila are those of the GF system. Voltage pulses given in the brain directly to the GF neurons exhibited the typical short latency responses (<1.3 msec) of a direct GF stimulation. DLM spikes followed stimulation of GF neurons up to 100 Hz in both wild type and hypnos mutants. Within 15–25 sec after the onset of anoxia, this evoked DLM response was lost, and it continued to be absent during the 5-min period of anoxia. After the reintroduction of room air, the response returned within 1–2 min, with no difference between C-S and mutant flies in the recovery time of the GF system. These data indicate that the hypnos mutations do not eliminate any gene products that might be necessary for axonal conduction or synaptic function between the GF neurons and the DLM.

Because no defect was detected in the GF system, we examined the effect of anoxia on the interneurons in the Drosophila brain that are presynaptic to GF. Stimulation of eye neurons, using low voltages, evoked spikes in the DLM with a long latency (4 msec) (13). Experiments were carried out in three of the four mutations (hypnos-2P,L, Hypnos-1N) and on wild-type flies. In one mutant (hypnos-2P), which had a severe phenotype, long-latency evoked potentials could not be obtained, irrespective of the voltage and duration used. Flies with an allele of this locus (hypnos-2L) or with the other severe mutation (Hypnos-1N) (n = 25) had a baseline long latency recording that was similar to that of C-S flies (n = 10). However, during recovery, whereas the DLM of wild-type flies started to respond after 2 min into recovery (Fig. 4A), flies with these two mutations had a much longer time to first evoked potential, with some mutant flies requiring up to 25–30 min for the first evoked response to occur (Fig. 4 A–C). As a measure of a further stage of recovery, we studied the time it took before the flies could respond to consecutive stimuli at 0.05 Hz without failure (Fig. 4D). Both hypnos-2L and Hypnos-1N mutants took about three times as long as wild types to recover to this degree. These data strongly suggest that the mutation has a profound effect on synaptic transmission in the central nervous system, most likely in neurons proximal to the GF system. Furthermore, we believe that the defects in the mutants are not general ones that affect all synapses. The reason for this is that our studies on shaking B mutants (13, 14), which have specific defective connectivity distally to the GF, do not have an abnormal recovery from anoxia (data not shown).

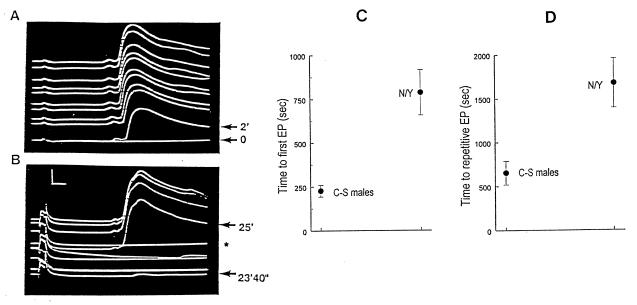

Figure 4.

Recovery from anoxia of DLM evoked potential in wild-type and mutant flies. DLM-evoked potentials, which are present during baseline in both wild type and mutant Hypnos-1N, are abolished within 20–25 sec of the start of the 5-min anoxic period. (A) A series of consecutive traces of evoked potentials in a single wild-type fly. Bottom trace is recorded at the end of anoxia or 0 min into reoxygenation, and evoked potential is still absent (bottom arrow). First evoked potential during recovery occurs at 2 min after the start of reoxygenation. Subsequent stimulation at 0.05 Hz shows persistent responsiveness. (B) A series of consecutive traces in a single hypnos-1N mutant fly with a very severe phenotype. Even after 23 min and 40 sec into reoxygenation, no response was seen, and the first evoked potential elicited occurred at 25 min, followed at least once (★) by a failed response to stimulation. (C) Means ± SE of the time to first evoked potential (EP) in wild-type (C-S males) and Hypnos-1N mutants. (D) Means ± SE of time to repetitive EP (10 consecutive stimuli at 0.05 Hz without failure) for the same two groups of flies. Stimulation parameters were 6 V, 0.3-msec duration at 0.05 Hz. [Bars = 1 msec (horizontal) and 10 mV (vertical).]

The current genetic screen is not saturated and is restricted to the X chromosome. However, that we had to screen more than 10,000 mutagenized flies to obtain three loci (with one locus hit twice) suggests that a limited number of genes can be mutated in Drosophila to produce similar phenotypes. Because these mutations profoundly disrupt the recovery from anoxia, we believe that this approach can be used effectively to dissect the genetic basis of responses to low O2.

It is now becoming clear that in almost all aspects of biology, from ion channels (16–19) to embryonic development and to neural development (20–24), mammals and Drosophila use very similar complements of genes. Therefore, it is very likely that characterization of Drosophila genes necessary for recovery from anoxia will lead us to uncover molecular mechanisms in a variety of species, including mammals.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mr. R. Garcia for his technical assistance.

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the Proceedings Office.

Abbreviations: DLM, dorsal longitudinal muscle; GF, giant fiber; C-S, Canton-S.

References

- 1.Jacobson M D, Raff M C. Nature (London) 1995;374:814–816. doi: 10.1038/374814a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shimizu S, Eguchi Y, Kamiike W, Itoh Y, Hasegawa J, Yamabe K, Otsuki Y, Matsuda H, Tsujimoto Y. Cancer Res. 1996;56:2161–2166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Graeber T G, Osmanian C, Jacks T, Housman D E, Koch C J, Lowe S W, Giaccia A J. Nature (London) 1996;379:88–91. doi: 10.1038/379088a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shimizu S, Eguchi Y, Kosaka H, Kamiike W, Matsuda H, Tsujimoto Y. Nature (London) 1995;374:811–813. doi: 10.1038/374811a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clegg J S, Jackson S A, Warner A H. Exp Cell Res. 1994;212:77–83. doi: 10.1006/excr.1994.1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foe V E, Alberts B M. J Cell Biol. 1985;100:1623–1636. doi: 10.1083/jcb.100.5.1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haddad G G, Jiang C. Prog Neurobiol. 1993;40:277–318. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(93)90014-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi D W. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1990;13:171–182. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.13.030190.001131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cummins T R, Donnelly D F, Haddad G G. J Neurophysiol. 1991;66:1471–1482. doi: 10.1152/jn.1991.66.5.1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friedman J F, Haddad G G. J Neurosci. 1993;13:63–72. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-01-00063.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haddad G G, Donnelly D F. J Physiol. 1990;429:411–428. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krishnan S N, Sun Y-A, Mohsenin A, Wyman R J, Haddad G G. J Insect Physiol. 1997;43:203–210. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1910(96)00084-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baird D H, Schalet A P, Wyman R J. Genetics. 1990;126:1045–1059. doi: 10.1093/genetics/126.4.1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krishnan S N, Frei E F, Swain G P, Wyman R J. Cell. 1993;73:967–977. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90274-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tanouye M A, Wyman R J. J Neurophysiol. 1980;44:405–421. doi: 10.1152/jn.1980.44.2.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jan L Y, Jan Y N. Cell. 1992;69:715–718. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90280-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baldwin T J, Isacoff E, Li M, Lopez A, Shang M, Tsaur M L, Yan Y N, Jan L Y. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 1992;57:491–499. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1992.057.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salkoff L, Baker K, Butler A, Covarrubias M, Pak M D, Wei A. Trends Neurosci. 1992;15:161–166. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(92)90165-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wei A, Covarrubias M, Butler A, Baker K, Pak M D, Salkoff L. Science. 1990;248:599–603. doi: 10.1126/science.2333511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Halder G, Callaerts P, Gehring W J. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1995;5:602–609. doi: 10.1016/0959-437x(95)80029-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peifer M, Wieschaus E. J Mol Evol. 1993;36:224–233. doi: 10.1007/BF00160477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quiring R, Walldorf U, Kloter U, Gehring W J. Science. 1994;265:785–789. doi: 10.1126/science.7914031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Artavanis-Tsakonas S, Matsuno K, Fortini M E. Science. 1995;268:225–232. doi: 10.1126/science.7716513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chang H C, Karim F D, O’Neill E M, Rebay I, Solomon N M, Therrien M, Wassarman D A, Wolff T, Rubin G M. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 1994;59:147–153. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1994.059.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]