Abstract

Okadaic acid (OA) is a strong tumor promoter of mouse skin carcinogenesis and also a potent inhibitor of serine/threonine protein phosphatases. OA induces various genetic alterations in cultured cells, such as diphtheria-toxin-resistance mutations, sister chromatid exchange, exclusion of exogenous transforming oncogenes, and gene amplification. The present study revealed that it caused minisatellite mutation (MSM) at a high frequency in NIH 3T3 cells, although no microsatellite mutation was found. Nine of 31 clones (29%) exhibited MSM after 6 days of OA treatment, as opposed to only 1 of 30 clones (3%) without OA exposure. Moreover, NIH 3T3 cells treated with OA acquired tumorigenicity in nude mice, giving rise to 7 tumors within 25 weeks in 20 sites where 3 × 106 cells were injected. In contrast, the same numbers of untreated cells gave rise to only one tumor, and the tumor grew much slower. All of three OA-induced tumors examined manifested the MSM. The findings thus point to a molecular mechanism by which OA could function as a tumor promoter, and also the biological relevance of the induction of MSM in the tumorigenic process by OA.

Keywords: genomic instability, tumorigenicity

Okadaic acid (OA) was originally isolated from the marine sponge Halichondria okadai (1). It was subsequently shown to be a tumor promoter as potent as phorbol 12-tetradecanoate 13-acetate (12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate; TPA), although it does not activate protein kinase C. OA promotes mouse skin carcinogenesis in vivo (2) and transforms BALB/3T3 mouse fibroblasts in vitro (3) after initiation with 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene and 3-methylcholanthrene, respectively. No initiating activities of OA were detected in a two-step model of carcinogenesis either in vitro or in vivo (2, 3). Further, no mutations were induced in Salmonella typhimurium with or without rat liver S9 (postmitochondrial) metabolic activation system (4), and there has been no evidence that OA directly interacts with DNA. However, we have found that OA induces various genomic alterations in cultured cells, such as mutations endowing diphtheria-toxin resistance (4), sister chromatid exchange in the presence of bromodeoxyuridine (5), and loss of exogenous transforming oncogenes (6). OA also induces karyotype instability (7) and gene amplification under certain circumstances (8). Although the molecular mechanisms underlying the genotoxic activity of OA have not been fully elucidated as yet, all the observed genetic alterations point to the induction of recombination events rather than introduction of point mutations. Because OA has another biological aspect as a potent inhibitor of serine/threonine protein phosphatases, especially types 2A and 4 (9, 10), alterations of the phosphorylation status of cellular proteins or other epigenetic events could be the molecular mechanisms involved.

A minisatellite (MS) (11), also called a variable number of tandem repeats (VNTR) (12), is an array of repeats of 5–100 nucleotides flanked by locus-specific sequences. MSs are dispersed throughout the entire genomes of all vertebrates (13) and are genetically stable sequences in somatic cells (14), but they are known to be hot spots for meiotic recombination (15). Recently, they have been demonstrated to be altered even in somatic cells when the cells are exposed to various chemical carcinogens and ultraviolet irradiation (16), and they are also altered in various human and experimental animal tumors (17–21).

In the present study, we investigated the molecular basis of genomic instability induced by OA, using MSs and microsatellites (MIs) as markers. MIs are composed of tandem repeats of simple sequences ranging from one to four nucleotides, and they are frequently altered in a variety of tumors as a consequence of mutations in mismatch repair genes (22). Furthermore, we demonstrated that the induction of MS mutation (MSM) by OA can contribute to the acquisition of in vivo tumorigenicity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals, Cells, and Cell Culture Conditions.

OA (molecular weight: 805.2) was purchased from Wako Pure Chemical (Osaka). The NIH 3T3 cell line, originally obtained from M. Wigler (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory), was cultured as described (23). To analyze the effects of OA on cell growth, aliquots of 104 cells in 1 ml of culture medium were seeded onto 30-mm plates, and OA with various amounts in 6 μl of dimethyl sulfoxide as a solvent was added the next day. Cells were collected at appropriate times and cells were counted. Each experiment was carried out in triplicate, repeated twice.

Subcloning of NIH 3T3 Cells After OA Treatment.

Aliquots of 2 × 105 cells in 10 ml were seeded onto 100-mm culture plates 1 day before starting the experiments. The next day (day 1), OA was added to the medium at the concentration of 0 or 6 ng/ml (7.5 nM). The cells were then cultured without changing the medium for 6 days and subjected to the subcloning procedure. Briefly, collected cells were suspended at a concentration of one per 400 μl of culture medium without OA, and 100-μl samples were replated in each well of 96-well plates and kept at 37°C for 2–3 weeks.

MS DNA Probe.

The pPc-1 plasmid (24), which contains 28 copies of 5′-GGGCA-3′ sequence as a repetitive unit flanked with locus-specific sequences at both ends, was digested with EcoRI and HindIII, and the Pc-1 MS fragment 1.0 kb in length was purified by GlassMax (GIBCO/BRL). The fragment was labeled with [α-32P]dCTP by using the Multiprime DNA labeling system (Amersham) as described earlier (25).

MI PCR Primers.

MI length alterations in 8 loci (D1Mit1, D1Jp1, D3Jp1, D5Jp5, D6Mit1, D9Jp2, Myc, and Int2) were analyzed by PCR-single strand length polymorphism (PCR-SSLP) as described previously (26). The Mit-series primers were purchased from Research Genetics (Huntsville, AL). The sequences of the Jp-series primers applied are listed below: D1Jp1 (chromosome 1), 5′-AATCAGACACTACACCACAG-3′/5′-TGTGGGAAGATGTGAACTTAC-3′; D3Jp1 (chromosome 3), 5′-GCTCCAGGGAATTTGATGCCT-3′/5-′CGCCTCATTGACAAGTGCTAA-3′; D5Jp5 (chromosome 5) 5′-GATCTGCTTATTACTTTCAGT-3′/5′-CTCCACATGTGTGCTGTGTGGTAC-3′; and D9Jp2 (chromosome 9), 5′-GATCTTGTCTTCAACCTTTAATTC-3′/5′-CCAAYACCACCCCA-TGATTTTGTA-3′.

DNA Fingerprint Analysis.

DNA from NIH 3T3 cells or tumor tissues developing in nude mice was extracted as described previously (27). Samples (2.5 μg) of each DNA were digested with HaeIII, HinfI, or MboI, size-fractionated by electrophoresis in 1.0% agarose gels in 1 x TAE buffer (40 mM Tris⋅HCl/40 mM acetic acid/1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) at 2 V/cm for 20–24 h, then DNA was capillary blotted onto GeneScreenPlus nylon membranes (DuPont) by using the alkaline transfer method according to the manufacturer’s protocol. After DNA was fixed by UV-crosslinking, prehybridization was performed in a solution of 4× SSC (1× SSC is 150 mM NaCl/15 mM sodium citrate, pH 7.0) and 1% SDS at 65°C for 2 h, and subsequent hybridization was performed in the same buffer containing 25 ng of 32P-labeled Pc-1 probe overnight. Membranes were then washed three times at 65°C in 1× SSC/0.5% SDS for 60 min and exposed to Kodak XAR film at room temperature for 1–7 days.

Assay for Tumorigenicity in Nude Mice.

Aliquots of 105 cells were cultured and propagated in either the presence or the absence of 7.5 nM OA for 6 days and then for an additional 2 days with fresh medium without OA. On experimental day 9, the cells were collected, rinsed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and resuspended in PBS. In groups of 10 mice, the shoulders on both sides of 5-week-old male BALB/cAJcl-nu mice (CLEA Japan, Osaka) were injected with 3 × 106 cells per site subcutaneously.

Establishment of Tumor Cell Lines.

Mice harboring tumors were sacrificed at appropriate times, and tumors were sterilely resected. Tumor tissues were minced and spread on 100-mm culture plates and allowed to sit for 10 min, and then 10 ml of culture medium was added to each plate. When cells had proliferated to near confluency, they were harvested and subjected to the subcloning procedure as described above.

RESULTS

Induction of MSM in NIH 3T3 Cells by OA.

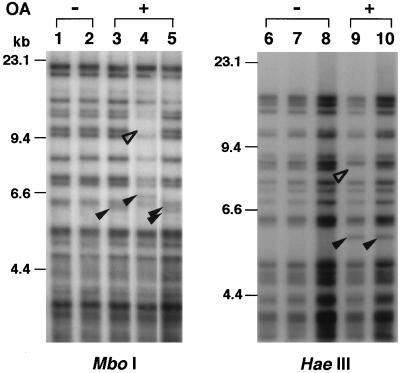

Thirty-one clones from the OA-treated and 30 from the untreated group were isolated and subjected to DNA fingerprint analysis. A representative fingerprint pattern with the Pc-1 probe is demonstrated in Fig. 1. When DNA samples digested with HaeIII were analyzed, approximately 20–25 MS bands were observed in common among samples between 4 and 20 kb in DNA length. Because bands smaller than 4 kb in length were barely distinguishable from each other under the experimental conditions, those over 4 kb were analyzed for the assay. Fingerprint patterns of MS sequences have been reported to be relatively stable in somatic cells (14); however, several altered MS bands (one extra band in lanes 3 and 10, two extra bands in lane 5, and one extra band along with a band deletion in lanes 4 and 9) were observed for DNA samples from OA-treated cells. We counted those clones as positives for MSM. The overall results are summarized in Table 1. Nine of 31 clones (29%) manifested MSM involving at least one locus in OA-treated clones, as opposed to only 1 of 30 untreated clones (3%).

Figure 1.

Pc-1 fingerprint analysis of cells with and without OA treatment. Aliquots (2.5 μg) of DNA from OA-untreated cells (−) and OA-treated cells (+) were digested with either MboI (Left) or HaeIII (Right) and electrophoresed in 1.0% agarose gels. Lanes 1, 2, and 6–8 are without OA treatment, and lanes 3–5, 9, and 10 are with OA treatment. Additional and deleted bands are indicated by filled and open arrowheads, respectively.

Table 1.

Induction of MSM-positive cells by OA treatment

| Treatment | No. of clones analyzed | Restriction enzymes used and no. of positives (%) |

|---|---|---|

| OA | 31 | 9 (29)* |

| HaeIII 2 | ||

| MboI 6 | ||

| HinfI 6 | ||

| None | 30 | 1 (3) |

| HaeIII 0 | ||

| MboI 1 | ||

| HinfI 0 |

Statistically significant (P < 0.01) in comparison with the no-treatment group.

Analysis of MI Length Alterations.

To assess the possible involvement of the mismatch repair system as a causative defect in MSM, MI length alterations were analyzed. A total of 8 loci of the mouse genome were analyzed in 48 clones of NIH 3T3 cells isolated after treatment with 7.5 nM OA for 6 days. No alterations were detected in any of the clones examined (data not shown).

Clones with MSM Lack Any Growth Advantage.

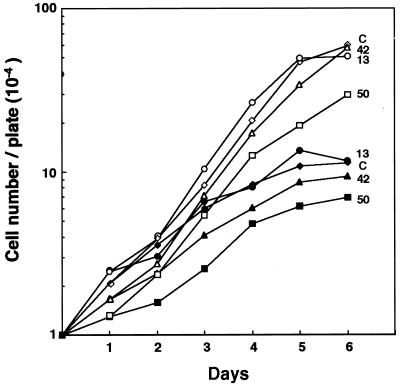

It is critically important to clarify whether clones having MSM have any growth advantage in the presence of OA, because there is a possibility that spontaneously altered clones could simply be selected by OA treatment. To address this issue, growth profiles for MSM-positive clones were analyzed in the presence or absence of 7.5 nM OA. As shown in Fig. 2, clones 13, 42, and 50 with MSM exhibited neither acceleration nor retardation of growth as compared with the original NIH 3T3 cells (clone C), regardless of the presence or the absence of OA. Thus it was confirmed that OA did induce MSM.

Figure 2.

Effects of OA on growth of clones with MSM. Cells (104) were plated onto 100-mm plates and were cultured without (open symbols) or with (closed symbols) addition of 7.5 nM OA on day 1. Clones 13, 42, and 50 were obtained after OA treatment and exhibited MSM. The growth profile of original NIH 3T3 is shown as C.

Tumorigenicity in Nude Mice.

To get further insight into whether MSM events are relevant to tumorigenesis, tumorigenicity was assayed by using whole groups of OA-treated cells as described in Materials and Methods, in which approximately 30% of the cells were expected to harbor MSM. Implantation of OA-treated cells at 20 sites gave rise to seven tumors, whereas untreated cells gave rise to only one tumor (data not shown). Three tumors from OA-treated cells, T1, T2, and T3, became visible by week 18, and then grew rapidly, doubling in volume within a week. The remainder of the tumors, including the one example derived from OA-untreated cells, appeared but grew much slower.

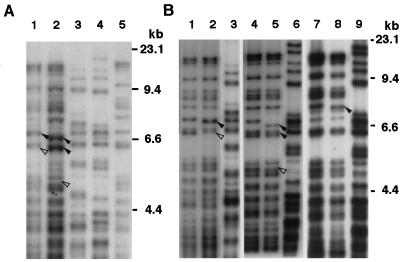

MSM in Tumor Cells.

To examine whether MSs were mutated in tumors developing in nude mice, DNA from tumors (T1 and T2) was subjected to fingerprint analysis with Pc-1 as a probe. Several MS band alterations were detected in both tumors (lanes 1 and 2 in Fig. 3A) compared with the original NIH 3T3 cells (lane 5) as indicated by arrowheads. Further, a different fingerprint pattern was observed in host mouse DNA (lanes 3 and 4), which clearly represented the highly polymorphic feature of MS sequences in individual animals as described previously (13). To eliminate the possibility of the DNA carry-over in tumor samples from host mice, we further analyzed primary tumor cell lines, TC1, TC2, and TC3, established from T1, T2, and T3, respectively (Fig. 3B). All three tumor lines examined possessed bands shifted from the original NIH 3T3 (arrowhead), as detected in DNA from tumor tissues.

Figure 3.

MS fingerprint analysis of nude mouse tumors and their cell lines. DNA samples extracted from tumors T1 and T2 (A) or tumor cell lines TC1, TC2, and TC3 (B) were subjected to MS fingerprint analysis using Pc-1 as a probe. (A) DNA (2.5 μg) was digested with HaeIII and separated in a 1.0% agarose gel. Lane 1, T1; lane 2, T2; lane 3, T1 host; lane 4, T2 host; and lane 5, NIH 3T3. (B) DNA (2.5 μg) from tumor cell lines was digested with HaeIII and analyzed. Lanes 1, 4, and 7, NIH 3T3; lane 2, TC1; lane 5, TC2; lane 8, TC3. Lanes 3, 6, and 9, DNA derived from the host mouse of each tumor. Arrowheads indicate the additional shifted (◂) or deleted (◃) bands as compared with the original NIH 3T3 cell.

DISCUSSION

OA has been demonstrated to be a strong tumor promoter in two-step carcinogenesis experiments both in vivo (2) and in vitro (3), exerting its tumor-promoting activity through a molecular mechanism distinct from that of TPA (28). However, efforts to explain this in terms of OA inhibition of protein phosphatases (8, 9) have not generated a complete understanding of the molecular mechanisms involved.

The present study clearly demonstrated that treatment with OA induces MSM in NIH 3T3 cells, the observed incidence of 29% of the total cell populations being significantly greater than in untreated cells (P < 0.01). We also demonstrated the acquisition of tumorigenicity by NIH 3T3 cells with OA treatment, and moreover, all three tumors analyzed manifested the MSM. These observations strongly support the idea that induction of MSM by OA is of essential relevance to its tumor-promoting activity. It would be more intriguing when it is clarified if TPA, which possesses biochemical activities distinct from OA as a potent tumor promoter, also induces MSM.

Several functions have been suggested for MSs, but their physiological relevance remains largely unclear. Some of the MSs, such as the insulin (INS)-VNTR (29), Ha-ras (HRAS1)-VNTR (30), and immunoglobulin heavy chain (IGH)-VNTR (31), are located in either the 5′ or the 3′ regions of the genes or in introns, and they can exert modulatory activity. A rare allele of HRAS1-VNTR at the 3′ end has been reported to have a significant association with common types of cancers, such as those in the breast, colorectum, and urinary bladder (32). Ovarian cancer risk in BRCA1 mutant carriers is also modified by the HRAS1-VNTR (33). INS-VNTR at the 5′ end correlates with the expression level of the insulin gene (34) and has been implicated in susceptibility to insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus type 2 (IDDM2) (35). The available evidence thus provides support for the attractive scenario that MSM may be involved in oncogenesis and other human disease (36).

The molecular mechanisms responsible for the induction of MSM have yet to be elucidated, although it is known to occur in somatic cells treated with DNA-damaging agents, such as N-OH-2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b]pyridine (16). There is, so far, no unequivocal evidence that OA directly interacts with DNA, but perturbation of the phosphorylation status of proteins through phosphatase inhibition could be a contributory cause. Among several plausible molecules, MS-binding proteins (Msbps) are strong candidates for involvement in MSM. Four types of Msbps have been identified so far and their biochemical properties have been partially characterized (37–39). Msbp-4 has been shown to be phosphorylated in vitro, and its binding activity to MS sequence is known to be modulated by phosphorylation status (39). Changes in the phosphorylation state of Msbps could lead to alteration in the recombination machinery and consequent induction of MSM.

In the case of human colon carcinogenesis, colorectal cancers without MI instability lose about 25% of alleles on average, while cancers with MI instability often lose none and are chromosomally relatively stable (40, 41). It seems likely that only one type of genomic instability, MI instability or gross chromosomal changes, is sufficient for cancers to acquire selective growth advantage. Impairment of the mismatch repair system is considered to result mainly in the introduction of point mutations. With regard to this, the findings observed in the present study are clearly different and may be based on the distinct molecular mechanism from the mismatch repair system. Lengauer et al. (42) have recently published data indicating that colorectal tumors without MI instability exhibit a defect in chromosomal segregation, resulting in gains or losses in the genome. The molecular mechanisms involved in MSM observed in the present study are largely unknown; however, they could be partly implicated in the gross chromosomal changes seen in tumors without MI instability.

In conclusion, the present results provide a novel pointer to the molecular mechanisms of the tumor-promoting activity of OA, possibly through the inhibition of serine/threonine protein phosphatase activity.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Cancer Research and by the Second Term of the Comprehensive 10-Year Strategy for Cancer Control from the Ministry of Health and Welfare of Japan, and by the Nishi Cancer Research Fund. H.I. is the recipient of a Research Resident Fellowship from the Foundation for Promotion of Cancer Research.

ABBREVIATIONS

- OA

okadaic acid

- TPA

phorbol 12-tetradecanoate 13-acetate (12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate)

- MS

minisatellite

- MI

microsatellite

- MSM

MS mutation

- VNTR

variable number of tandem repeats

- Msbp

MS-binding protein

References

- 1.Tachibana K, Sheuer P J, Tsukitani Y, Kikuchi H, van Eugen D, Clardy J, Gopichand Y, Schmitz F J. J Am Chem Soc. 1981;103:2471–2472. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suganuma M, Fujiki H, Suguri H, Yoshizawa S, Hirota M, Nakayasu M, Ojika M, Wakamatsu K, Yamada K, Sugimura T. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:1768–1771. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.6.1768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Katoh F, Fitzgerald D J, Giroldi L, Fujiki H, Sugimura T, Yamasaki H. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1990;81:590–597. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1990.tb02614.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aonuma S, Ushijima T, Nakayasu M, Shima H, Sugimura T, Nagao M. Mutat Res. 1991;250:375–381. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(91)90194-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tohda H, Nagao M, Sugimura T, Oikawa A. Mutat Res. 1993;289:275–280. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(93)90078-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nagao M, Shima H, Nakayasu M, Sugimura T. Mutat Res. 1995;333:173–179. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(95)00143-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuwabara K, Odani S, Takahashi Y, Arakawa M, Takagi N, Nagao M, Kominami R. Mol Carcinog. 1995;14:299–305. doi: 10.1002/mc.2940140411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang S J, Scavetta R, Lenz H J, Danenberg K, Danenberg P V, Schonthal A H. Carcinogenesis. 1995;16:637–641. doi: 10.1093/carcin/16.3.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bialojan C, Takai A. Biochem J. 1988;256:283–290. doi: 10.1042/bj2560283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brewis N D, Street A J, Prescott A R, Cohen P T. EMBO J. 1993;12:987–996. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05739.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wyman A R, White R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:6754–6758. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.11.6754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakamura Y, Leppert M, O’Connell P, Wolff R, Holm T, Culver M, Martin C, Fujimoto E, Hoff M, Kumlin E, White R. Science. 1987;235:1616–1622. doi: 10.1126/science.3029872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jeffreys A J, Wilson V, Thein S L. Nature (London) 1985;314:67–73. doi: 10.1038/314067a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jeffreys A J, Tamaki K, MacLeod A, Monckton D G, Neil D L, Armour J A L. Nat Genet. 1994;6:136–145. doi: 10.1038/ng0294-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wahls W P, Wallace L J, Moore P D. Cell. 1990;60:95–103. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90719-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kitazawa T, Kominami R, Tanaka R, Wakabayashi K, Nagao M. Mol Carcinog. 1994;9:67–70. doi: 10.1002/mc.2940090203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thein S L, Jeffreys A J, Gooi H C, Cotter F, Flint J, O’Connor N T J, Weatherall D J, Wainscoat J S. Br J Cancer. 1987;55:353–356. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1987.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matsumura Y, Tarin D. Cancer Res. 1992;52:2174–2179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boltz E M, Harnett P, Leary J, Houghton R, Kefford R F, Friedlander M L. Br J Cancer. 1990;62:23–27. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1990.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ledwith B J, Storer R D, Prahalada S, Manam S, Leander K R, van Zwieten M J, Nichols W W, Bradley M O. Cancer Res. 1990;50:5245–5249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ledwith B J, Joslyn D J, Troilo P, Leander K R, Clair J H, Soper K A, Manam S, Prahalada S, van Zwieten M J, Nichols W. Carcinogenesis. 1995;16:1167–1172. doi: 10.1093/carcin/16.5.1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu B, Parsons R, Papadopoulos N, Nicolaides N C, Lynch H T, Watson P, Jass J R, Dunlop M, Wyllie A, Peltomaki P, Chapelle A, Hamilton S R, Vogelstein B, Kinzler K W. Nat Med. 1996;2:169–174. doi: 10.1038/nm0296-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shima H, Tohda H, Aonuma S, Nakayasu M, DePaoli-Roach A A, Sugimura T, Nagao M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:9267–9271. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.20.9267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mitani K, Takahashi Y, Kominami R. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:15203–15210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feinberg A P, Vogelstein B. Anal Biochem. 1984;137:266–267. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(84)90381-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Toyota M, Ushijima T, Weisburger J H, Hosoya Y, Canzian F, Rivenson A, Imai K, Sugimura T, Nagao M. Mol Carcinog. 1996;15:176–182. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2744(199603)15:3<176::AID-MC3>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Plainview, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press; 1989. pp. 914–919. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lagenbach R, Elmore E, Barrett J C. Progress in Cancer Research and Therapy: Tumor Promoters: Biological Approaches for Mechanistic Studies and Assay Systems. Vol. 34. New York: Raven; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bell G I, Selby M J, Rutter W J. Nature (London) 1982;295:31–35. doi: 10.1038/295031a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Capon D J, Seeburg P H, McGrath J P, Hayflick J S, Edman U, Levinson A D, Goeddel D V. Nature (London) 1983;304:507–513. doi: 10.1038/304507a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Higgs D R, Goodbourn S E, Wainscoat J S, Clegg J B, Weatherall D J. Nucleic Acids Res. 1981;9:4213–4224. doi: 10.1093/nar/9.17.4213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krontiris T G, Devlin B, Karp D D, Robert N J, Risch N. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:517–523. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199308193290801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Phelan C M, Rebbeck T R, Weber B L, Devilee P, Ruttledge M H, Lynch H T, Lenoir G M, Stratton M R, Easton D F, Ponder B A, Cannon-Albright L, Larsson C, Goldgar D E, Narod S A. Nat Genet. 1996;12:309–311. doi: 10.1038/ng0396-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kennedy G C, German M S, Rutter W J. Nat Genet. 1995;9:293–298. doi: 10.1038/ng0395-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bennett S T, Lucassen A M, Gough S C, Powell E E, Undlien D E, Pritchard L E, Merriman M E, Kawaguchi Y, Dronsfield M J, Pociot F, Nerup J, Bouzekri N, Cambon-Thomsen A, Ronningen K S, Barnett A H, Bain S C, Todd J A. Nat Genet. 1995;9:284–292. doi: 10.1038/ng0395-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krontiris T G. Science. 1995;269:1682–1683. doi: 10.1126/science.7569893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Collick A, Dunn M G, Jeffreys A J. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:6399–6404. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.23.6399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wahls W P, Swenson G, Moore P D. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:3269–3274. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.12.3269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yamazaki H, Nomoto S, Mishima Y, Kominami R. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:12311–12316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aaltonen L A, Peltomaki P, Leach F S, Sistonen P, Pylkkanen L, Mecklin J-P, Jarvinen H, Powell S M, Jen J, Hamilton S R, Petersen G M, Kinzler K W, Vogelstein B, Chapelle A. Science. 1993;260:812–816. doi: 10.1126/science.8484121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kinzler K W, Vogelstein B. Cell. 1996;87:159–170. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81333-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lengauer C, Kinzler K W, Vogelstein B. Nature (London) 1997;386:623–627. doi: 10.1038/386623a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]