Abstract

We have recently found that okadaic acid, which shows strong inhibitory activity on protein serine/threonine phosphatases and tumor-promoting activity in vivo and in vitro, induces minisatellite mutation (MSM). Human tumors and chemically induced counterparts in experimental animals are also sometimes associated with MSM. In the present study, we demonstrated minisatellite (MS) instability in severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) cells in which the DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit (DNA-PKcs) is impaired. Cells from a SCID fibroblast cell line transformed by simian virus 40 large tumor antigen, SC3VA2, and from an embryonal SCID fibroblast cell line, SC1K, were cloned and propagated to 107 to 108 cells, and then subjected to subcloning. After propagation of each subclone to 107 to 108 cells, DNA samples were digested with HinfI and analyzed by Southern blotting using the Pc-1 MS sequence as a probe. Under low-stringency conditions, about 40 MS bands were detected, with 45% ± 6% and 37% ± 3% of SC3VA2 and SC1K cells, respectively, having MSM. In contrast, cells from the RD13B2 cell line, which was established from SCVA2 by introducing human chromosome 8q fragments, on which DNA-PKcs is known to reside, to complement the SCID phenotype, showed a very low frequency of MSM (3% ± 3%). The high frequencies of MSM in SC3VA2 and SC1K were significant, with no difference between the two. The present study clearly demonstrates that MS instability exists in SCID fibroblasts, suggesting that DNA-PKcs might be involved in the stable maintenance of MS sequences in the genome.

Keywords: minisatellite mutation, DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit

A great deal of evidence has accumulated in support of the conclusion that multiple genetic alterations are required for carcinogenesis, and it has been clearly shown that genomic instability contributes to cancer development and malignant progression. The genomic instability is caused by mutations in the cellular machinery that is responsible for accurate DNA replication. Further, instability is often due to deficiencies in the checking system for DNA damage in the G1/S and G2/M transition phases.

Genetic alterations in mismatch-repair genes participate in hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer (1, 2) and also in various sporadic cancers. Tumors demonstrate a high frequency of alteration in the number of repeat units of microsatellite (MI) sequences (3, 4). For instance, colon cancer cells with MI instability exhibit mutations in the type II transforming growth factor β receptor gene or BAX gene, and this might be causally involved in cancer development (5, 6).

There is another type of tandem repeat sequence called the minisatellite (MS) in vertebrates. MSs are tandem repeat arrays that are locus specific but have a consensus sequence that varies in the range of 5 to 100 bp, thousands of those being widely dispersed throughout the genome (7).

It has been shown that MS sequences are mutated at a remarkably high rate in germ cells through meiotic recombination (8), but they are relatively stable in somatic cells (9). However, in cells malignantly transformed by γ-irradiation or genotoxic carcinogens, MS mutations (MSMs) are observed more frequently than in nonmalignant immortalized cell lines (10, 11). MSMs have also been found in various human tumors (12, 13) and experimental animal tumors induced by chemical carcinogens (14, 15).

Recently, we have demonstrated that treatment of cultured cells with a tumor promoter, okadaic acid (OA), causes an increase in MSM (16). OA is an inhibitor of protein serine/threonine phosphatases and it has thus been suspected that changes in the phosphorylation state of some proteins might contribute to MSM. According to the model proposed by Jeffreys et al. (7, 9), mutations in MSs are initiated by the introduction of double-strand breaks (DSBs) into tandem repeat sequences. Thus, there is a possibility that genetic defects in the DSB repair system could cause MS instability.

Severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) mice are deficient in DSB repair and are thus sensitive to ionizing radiation (17–19). Their lymphocytes are unable to carry out V(D)J recombination (20). SCID cells have been demonstrated to be deficient in DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PK) (21), having a base-substitution mutation in the gene for its catalytic subunit, DNA-PKcs, which leads to truncation of the protein (22). DNA-PKcs has been mapped to the human chromosome 8q11 (21, 23). In this study, we demonstrated MS instability in SCID mouse-derived fibroblast cell lines by multilocus DNA fingerprint analysis. In addition, a SCID cell line harboring fragments of human chromosome 8 containing the human DNA-PKcs region was found to have restored MS instability.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Lines and Culture Conditions.

A simian virus 40 (SV40) large tumor antigen-transformed SCID mouse lung fibroblast cell line, SC3VA2, and its derivative RD13B2, in which the SCID phenotype has been complemented by introduction of human chromosome fragments of 8q11–12 and 8q21–22 regions (24), were used. SC1K, an embryonal fibroblast cell line from a SCID mouse (25), was kindly provided by H. Kimura (Shiga Medical College, Ohtsu, Japan). Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (JRH Biosciences, Lenexa, KS), glutamine (4 mM), penicillin (50 units/ml), and streptomycin (50 μg/ml) and subjected to two rounds of the cloning procedure. Individual clones obtained by the first cloning were propagated to approximately 107 to 108 cells, and then aliquots were subjected to subcloning and further propagation to 107 to 108 cells. DNA was extracted from the clones and their subclones.

Preparation of Genomic DNA.

DNA from cells was extracted as described earlier (26) with some modifications. In brief, lysis buffer (100 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 8.5/5 mM EDTA/0.2% SDS/200 mM NaCl/100 μg/ml proteinase K) was directly added to the culture dish, and the dish was incubated overnight at 37°C. DNA was precipitated by addition of an equal volume of isopropyl alcohol to the dish, rinsed with 70% (vol/vol) ethanol, and then dissolved in TE buffer (10 mM Tris⋅HCl/1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0).

MS DNA Probe.

A plasmid carrying an MS sequence, Pc-1, was kindly provided by R. Kominami (Niigata University School of Medicine, Niigata, Japan). Pc-1 consists of (GGGCA)28 flanked with locus-specific sequences (27). The inserted Pc-1 sequence was isolated from the plasmid and labeled with [α-32P]dCTP by the random priming method using the Multiprime DNA labeling system (Amersham).

DNA Fingerprint Analysis.

Southern blot analysis was performed, using Pc-1 as a probe under low-stringency conditions. Samples (2.5 μg) of genomic DNA were digested with restriction enzyme HinfI, electrophoresed in 1.2% agarose gels in 1× TAE buffer (40 mM Tris⋅HCl/40 mM acetic acid/1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) at 3 V/cm for 14–16 h, and Southern blot analysis was performed as described (16).

MI Analysis.

The following 10 MI loci were amplified by PCR: D1Mit1, D3Mit4, D3Mit3, D5Mit99, D6Mit1, D7Mit55, D8Mit12, D9Mit263, D12NDS2, and D13Mit9. PCR primers were included in the murine genome screening set, Mouse MapPairs (Research Genetics, Huntsville, AL). PCR products were labeled with [α-32P]dCTP, electrophoresed through denaturing 6% polyacrylamide gels, and autoradiographed.

RESULTS

MS in the SCID Cells: Analysis of Clones.

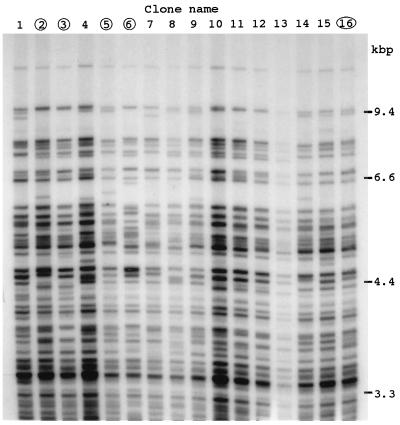

MSM was evaluated, in fibroblast cells derived from SCID mice in which DNA-PKcs is impaired, by fingerprint analysis after cloning. Totals of 25, 30, and 12 clones were obtained from SC3VA2, an SV40-transformed line, SC1K, an embryonal line, and RD13B2, an SC3VA2-derived line whose SCID phenotype had been complemented by fragments of human chromosome 8 on which DNA-PKcs resides, respectively. Fingerprint analysis of MS was performed for HinfI-digested DNA, using Pc-1 as a probe. About 40 bands were distinguishable in each DNA sample under the conditions used. Surprisingly, clones from SC3VA2 showed an extremely high frequency of MSM, so that band patterns of all 25 clones were distinct from one another (Fig. 1). In the embryonal SCID cell line, SC1K, MSMs were detected in 22 of 30 clones. On the other hand, in the RD13B2 cell line retaining human chromosome 8 fragments, MSMs were detected at a lower frequency, in 3 of the 12 clones (data not shown).

Figure 1.

DNA fingerprints of first subclones of SC3VA2 cells. Genomic DNA was digested with HinfI and hybridized with the 32P-labeled MS probe, Pc-1. About 40 MS bands were detected in each clone at the range of 3–10 kbp. Note the band patterns of each clone were distinct from one another. The clones circled were subjected to subcloning.

MSMs might accumulate in cells during the long-term cell culture if they have no adverse effects on cell growth. To clarify how frequently the MSM occurs during short-term cell culture, we randomly selected several of the clones isolated from each cell line and propagated them to 107 to 108 cells, before subjecting them to subcloning.

MS Instability in the SCID Cells: Analysis of Subclones.

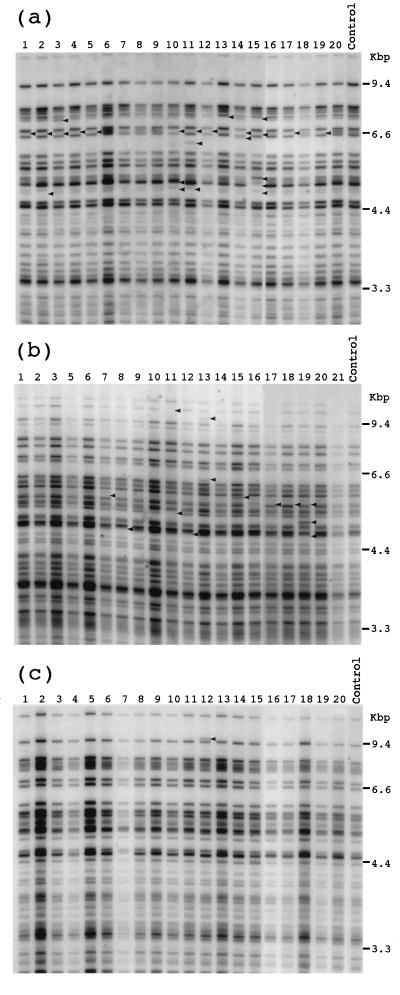

We subjected 5, 2, and 3 clones of SC3VA2, SC1K, and RD13B2, respectively, to subcloning, and 18–20 subclones were obtained from each clone. Results of fingerprint analysis of these cells are summarized in Table 1, and typical fingerprints are shown in Fig. 2. MSMs were detected in about half of the subclones obtained from the SC3VA2 and SC1K cell lines. Some subclones of SC3VA2 and SC1K showed the same MSM fingerprints (e.g., lanes 1, 4, 5, 12, 17, and 19 of Fig. 2a and lanes 7, 17, and 18 of Fig. 2b), so that members of these subclone groups could have been the progenies of the one having MSM. In the parental clones, the mutants might be present as fairly large populations, but could not be detected due to the intrinsic property of the mutation, loss of a faint band. By counting the MSM-positive cells that had different fingerprints, mutation frequencies of SC3VA2 and SC1K were estimated to be 45% ± 6% and 37% ± 3%, respectively (see Table 1). On the other hand, only 3% ± 3% subclones of RD13B2, the complemented cell line, showed the MSM. Although there was no significant difference between SC3VA2 and SC1K (χ2 = 0.7, P > 0.1), they were evidently different from the value of RD13B2 (χ2 = 31.4, P < 0.001 for SC3VA and χ2 = 19.1, P < 0.001 for SC1K). Thus, we conclude that SCID cells have MS instability.

Table 1.

MSM in subclones

| Cell line | Name of clone | No. of subclones analyzed | No. of subclones with distinct mutations (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SC3VA2 | 2 | 20 | 11 (55) |

| 3 | 20 | 8 (40) | |

| 5 | 20 | 8 (40) | |

| 6 | 20 | 9 (45) | |

| 16 | 20 | 9 (45) | |

| Total | 100 | 45 (45 ± 6) | |

| SC1K | 13 | 18 | 7 (39) |

| 29 | 20 | 7 (35) | |

| Total | 38 | 14 (37 ± 3) | |

| RD13B2 | 4 | 20 | 1 (5) |

| 6 | 20 | 1 (5) | |

| 9 | 20 | 0 (0) | |

| Total | 60 | 2 (3 ± 3) |

Figure 2.

Representative DNA fingerprints of subclones of SC3VA2 (a), SC1K (b), and RD13B2 (c) cells. Controls were their parental clones. Genomic DNA was digested with HinfI and hybridized with the 32P-labeled MS probe Pc-1. Changes in the MS bands are marked by arrowheads.

We also evaluated MI instability in 80 subclones—namely 20 each from four clones of SC3VA2–2, SC3VA2–3, RD13B2–4, and RD13B2–6—for 10 MI loci by PCR, but no MI mutations could be found (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

In the present study we were able to demonstrate MS instability in SCID fibroblast cell lines by DNA fingerprint analysis after two rounds of cloning. During the period in which a single cell that was obtained by the first cloning propagates to 107 to 108 cells, MSMs were induced. Because of the sensitivity of DNA fingerprint analysis, the MSMs detected might be those that were already present in the parental clone (107 to 108 cells) or induced at the relatively early phase of growth of the second clone.

The SCID fibroblast cell line derived from a SCID embryo and that transformed with SV40-large tumor (T) antigen showed similar MSM levels. Thus, no significant contribution of SV40 large T to the induction of MS instability by the DNA-PKcs deficiency was detected, although a slightly higher frequency of MSM was observed with the large T transformant. The effect of only SV40 large T on MS sequence remains to be determined. Further, MS instability was repressed in RD13B2, which was derived from SC3VA2 with introduction of human chromosome fragments containing 8q11–12 and 21–22 regions. The chromosomal locus for DNA-PKcs identified as a complement of SCID function has been assigned to human chromosome 8q11 (21, 23). We also confirmed the expression of the human DNA-PKcs protein in the RD13B2 cell by the immunoblot analysis with an anti-human DNA-PKcs polyclonal antibody (Serotec) (data not shown). Although we could not eliminate the possibility that the MS instability was restored by other unknown factors existing in the introduced fragments of human chromosome 8, DNA-PKcs is a strong candidate for this restoration. The frequency of the MSM observed in RD13B2 cells was similar to that found in our study of NIH 3T3 cells (16) and by others working with non-SCID cell lines (11, 28).

Since MSM has been detected in various human neoplasms (12, 13) as well as in experimental animal tumors (14, 15), it is suspected that MS instability, like MI instability, is involved in cancer development. It is known that SCID mice spontaneously develop lymphomas, and mutations in the p53 and Scid genes cooperate in this tumorigenesis; p53−/− Scid double-mutant mice develop lymphomas earlier than their p53−/− counterparts (29). However, it has not yet been established whether SCID mice are sensitive to chemical-caused cancer development in other organs. Because the number of genetic alterations required for development of lymphoma is small (30), it is very plausible that the SCID mouse is also sensitive to carcinogenesis of various organs when initiation is provoked with DNA-damaging agents.

In this study, analysis of migration changes of DNA fragments that hybridized with the Pc-1 probe under low-stringency conditions, after digestion with the HinfI restriction enzyme, revealed appearance, loss, and shift of bands. Most bands we detected under this condition seem to be MS sequences because they were shifted in different strains of mice (unpublished result) and alterations were therefore evaluated as MSM. Some of the subclones had two or more migration-altered bands, although the alteration patterns of bands—appearance, loss, or shift—sometimes could not be distinguished. So, we determined the ratios of MSM-positive subclones. Although some bands showed differences in relative intensity, these were not evaluated as MSM. The gross changes were presumably due to rearrangement of DNA in the MS sequences, and base-change mutation at the HinfI restriction site is not a plausible mechanism, as judged on the basis of the mutation frequencies (the MSM rate is roughly estimated to be about 10−3 per cell division per locus).

As for the molecular mechanisms of MSM in somatic cells, it was proposed by Jeffreys and Neumann that unequal sister chromatid exchange and intramolecular recombination rather than replication slippage might be involved (31). Our results support this idea on the basis that we could not detect any length alterations in MI sequences.

Although DSBs have been suggested to be a possible causal factor for MSM in germ cells, their role in somatic cells has yet to be clarified. MSM induced by x-irradiation was detected only with a specific sequence (11). DNA-PKcs forms complexes with a heterodimer of Ku70 and Ku86 at the end of a DSB, and thereby gains high protein kinase activity (32). This activity has been demonstrated to be involved in the repair of DSBs. At present, it is unclear whether Ku70 or Ku86 deficiency can induce MS instability.

ATM (the gene product of ataxia–telangiectasia mutated), another member of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-related kinase family, like DNA-PKcs (33, 34), functions as a monitor of DNA damage during the cell proliferation cycle, at G1/S, S, and G2/M, and loss of ATM function is known to result in genomic instability (35). DNA-PKcs does not appear to be involved in G1/S or G2/M arrest (36, 37), but rather may be necessary for exit from the DNA damage-induced G2 checkpoint arrest (38). Cells that remain at this checkpoint will not be able to survive. Therefore, the MS instability detected in SCID cells may not imply functional loss of the cell cycle check system. SCID cells are known to be sensitive to DSBs in the G1/S but not the G2 phase, and involvement of a pathway other than DNA-PK for repair of DSBs in the G2 phase has been proposed (38). On the other hand, as sister chromatid exchange occurs in the G2 phase (39) it is considered that DNA-PK may function to ensure accurate homologous recombination. The precise mechanisms underlying MS instability remain to be elucidated.

We recently found that OA induces MSM in NIH 3T3 cells (16). Because DNA-PK has been demonstrated to be inactivated through autophosphorylation (40) or phosphorylation by the c-Abl tyrosine kinase, whose activity is increased by phosphorylation with DNA-PK (41), this phosphorylation feedback mechanism may be perturbed in NIH 3T3 cells treated with OA. This point warrants further attention.

In conclusion, the present study suggests a new approach to clarification of the mechanisms of the genomic instability that plays critical roles in malignant progression during carcinogenesis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Hiroshi Kimura for providing us with SC1K cells and Prof. Ryo Kominami for the Pc-1 plasmid. This study was supported by Grants-in-Aid for the Second Term of the Comprehensive 10-Year Strategy for Cancer Control from the Ministry of Health and Welfare of Japan and by the Nishi Cancer Research Fund. H.I. is the recipient of a Research Resident Fellowship from the Foundation for Promotion of Cancer Research.

ABBREVIATIONS

- MI

microsatellite

- MS

minisatellite

- MSM

minisatellite mutation

- OA

okadaic acid

- DSB

double-strand break

- SCID

severe combined immunodeficiency

- DNA-PK

DNA-dependent protein kinase

- DNA-PKcs

catalytic subunit of DNA-PK

- SV40

simian virus 40

References

- 1.Leach F S, Nicolaides N C, Papadopoulos N, Liu B, Jen J, et al. Cell. 1993;75:1215–1225. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90330-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bronner C E, Baker S M, Morrison P T, Warren G, Smith L G, Lescoe M K, Kane M, Earabino C, Lipford J, Lindblom A, Tannergard P, Bollag R J, Godwin A R, Ward D C, Nordenskjold M, Fishel R, Kolodner R, Liskay R M. Nature (London) 1994;368:258–261. doi: 10.1038/368258a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aaltonen L A, Peltomaki P, Leach F S, Sistonen P, Pylkkanen L, Mecklin J P, Jarvinen H, Powell S M, Jen J, Hamilton S R, Petersen G M, Kinzler K W, Vogelstein B, de la Chapelle A. Science. 1993;260:812–816. doi: 10.1126/science.8484121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ionov Y, Peinado M A, Malkhosyan S, Shibata D, Perucho M. Nature (London) 1993;363:558–561. doi: 10.1038/363558a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Markowitz S, Wang J, Myeroff L, Parsons R, Sun L, Lutterbaugh J, Fan R S, Zborowska E, Kinzler K W, Vogelstein B, Brattain M, Willson J K V. Science. 1995;268:1336–1338. doi: 10.1126/science.7761852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rampino N, Yamamoto H, Ionov Y, Li Y, Sawai H, Reed J C, Perucho M. Science. 1997;275:967–969. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5302.967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jeffreys A J, Allen M J, Armour J A, Collick A, Dubrova Y, Fretwell N, Guram T, Jobling M, May C A, Neil D L, Neumann R. Electrophoresis. 1995;16:1577–1585. doi: 10.1002/elps.11501601261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jeffreys A J, Wilson V, Kelly R, Taylor B A, Bulfield G. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:2823–2836. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.7.2823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jeffreys A J, Tamaki K, MacLeod A, Monckton D G, Neil D L, Armour J A. Nat Genet. 1994;6:136–145. doi: 10.1038/ng0294-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Honma M, Mizusawa H, Sasaki K, Hayashi M, Ohno T, Tanaka N, Sofuni T. Mutat Res. 1994;304:167–179. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(94)90208-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paquette B, Little J B. Cancer Res. 1992;52:5788–5793. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thein S L, Jeffreys A J, Gooi H C, Cotter F, Flint J, O’Connor N T, Weatherall D J, Wainscoat J S. Br J Cancer. 1987;55:353–356. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1987.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsumura Y, Tarin D. Cancer Res. 1992;52:2174–2179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ledwith B J, Storer R D, Prahalada S, Manam S, Leander K R, van Zwieten M J, Nichols W W, Bradley M O. Cancer Res. 1990;50:5245–5249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ledwith B J, Joslyn D J, Troilo P, Leander K R, Clair J H, Soper K A, Manam S, Prahalada S, van Zwieten M J, Nichols W W. Carcinogenesis. 1995;16:1167–1172. doi: 10.1093/carcin/16.5.1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakagama H, Kaneko S, Shima H, Inamori H, Fukuda H, Kominami R, Sugimura T, Nagao M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:10813–10816. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.20.10813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fulop G M, Phillips R A. Nature (London) 1990;347:479–482. doi: 10.1038/347479a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hendrickson E A, Qin X Q, Bump E A, Schatz D G, Oettinger M, Weaver D T. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:4061–4065. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.10.4061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Biedermann K A, Sun J R, Giaccia A J, Tosto L M, Brown J M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:1394–1397. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.4.1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schuler W, Weiler I J, Schuler A, Phillips R A, Rosenberg N, Mak T W, Kearney J F, Perry R P, Bosma M J. Cell. 1986;46:963–972. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90695-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blunt T, Finnie N J, Taccioli G E, Smith G C, Demengeot J, Gottlieb T M, Mizuta R, Varghese A J, Alt F W, Jeggo P A, Jackson S P. Cell. 1995;80:813–823. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90360-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Danska J S, Holland D P, Mariathasan S, Williams K M, Guidos C J. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:5507–5517. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.10.5507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kirchgessner C U, Patil C K, Evans J W, Cuomo C A, Fried L M, Carter T, Oettinger M A, Brown J M. Science. 1995;267:1178–1183. doi: 10.1126/science.7855601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Komatsu K, Kubota N, Gallo M, Okumura Y, Lieber M R. Cancer Res. 1995;55:1774–1779. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kimura H, Terado T, Komatsu K, Nozawa A, Ikebuchi M, Aoyama T. Radiat Res. 1995;142:176–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laird P W, Zijderveld A, Linders K, Rudnicki M A, Jaenisch R, Berns A. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:4293. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.15.4293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mitani K, Takahashi Y, Kominami R. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:15203–15210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kitazawa T, Kominami R, Tanaka R, Wakabayashi K, Nagao M. Mol Carcinog. 1994;9:67–70. doi: 10.1002/mc.2940090203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nacht M, Strasser A, Chan Y R, Harris A W, Schlissel M, Bronson R T, Jacks T. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2055–2066. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.16.2055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Little M P. Biometrics. 1995;51:1278–1291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jeffreys A J, Neumann R. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6:129–136. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.1.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jackson S P, Jeggo P A. Trends Biochem Sci. 1995;20:412–415. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)89090-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hartley K O, Gell D, Smith G C, Zhang H, Divecha N, Connelly M A, Admon A, Lees-Miller S P, Anderson C W, Jackson S P. Cell. 1995;82:849–856. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90482-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Keith C T, Schreiber S L. Science. 1995;270:50–51. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5233.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meyn M S. Cancer Res. 1995;55:5991–6001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang L, Clarkin K C, Wahl G. Cancer Res. 1996;56:2940–2944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rathmell W K, Kaufmann W K, Hurt J C, Byrd L L, Chu G. Cancer Res. 1997;57:68–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee S E, Mitchell R A, Cheng A, Hendrickson E. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:1425–1433. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.3.1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paulovich A G, Toczyski D P, Hartwell L H. Cell. 1997;88:315–321. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81870-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chan D W, Lees-Miller S P. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:8936–8941. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.15.8936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kharbanda S, Pandey P, Jin S, Inoue S, Bharti A, Yuan Z, Weichselbaum R, Weaver D, Kufe D. Nature (London) 1997;386:732–735. doi: 10.1038/386732a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]