Abstract

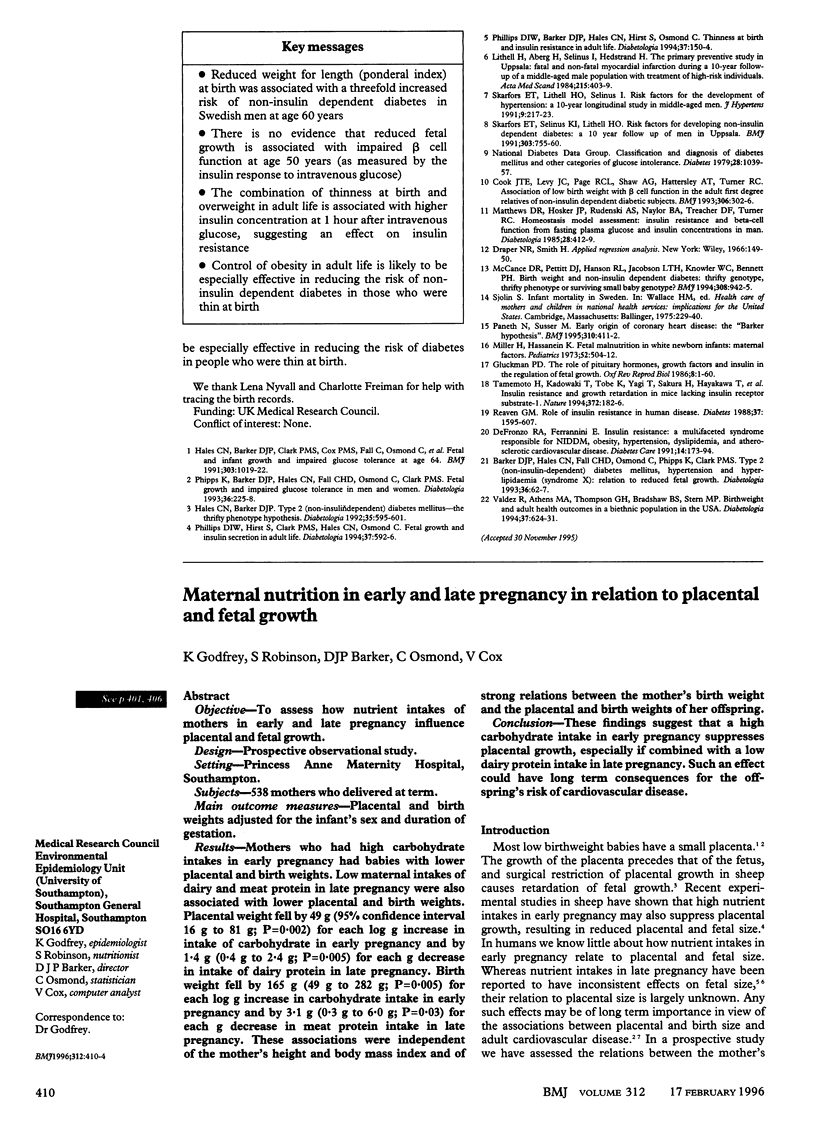

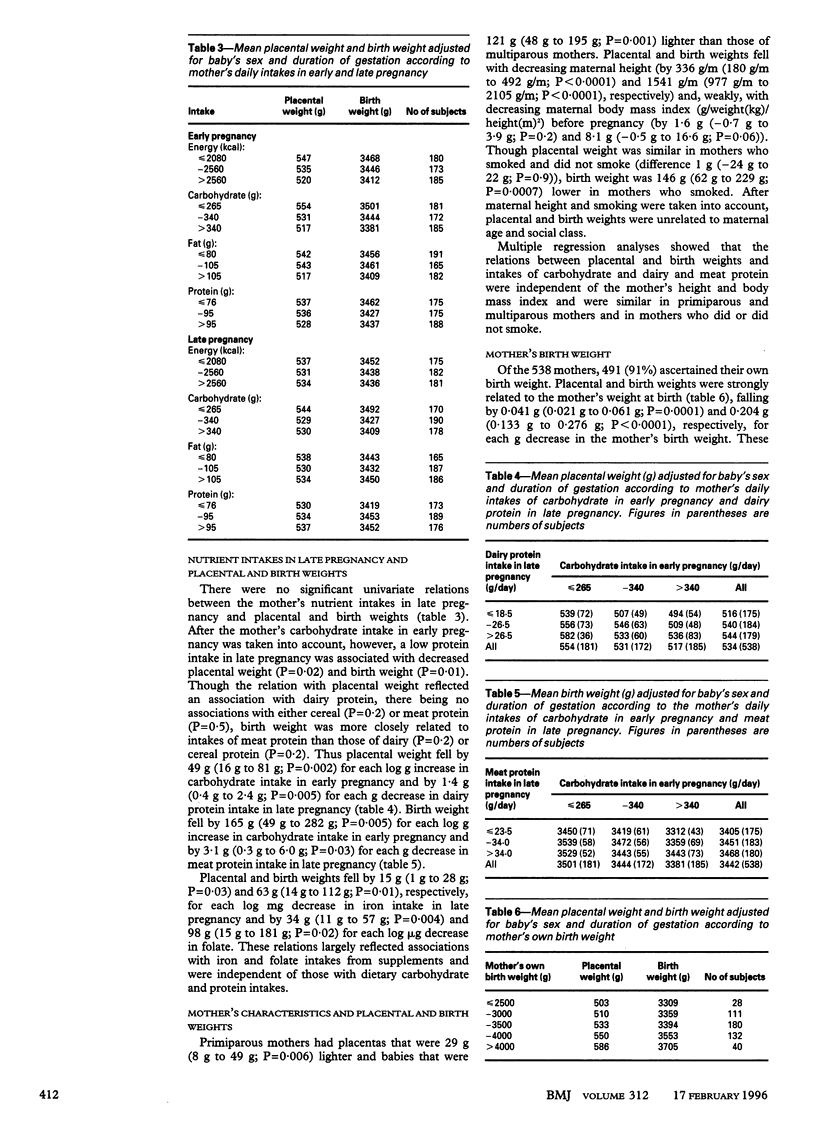

OBJECTIVE: To assess how nutrient intakes of mothers in early and late pregnancy influence placental and fetal growth. DESIGN: Prospective observational study. SETTING: Princess Anne Maternity Hospital, Southampton. SUBJECTS: 538 mothers who delivered at term. MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES: Placental and birth weights adjusted for the infant's sex and duration of gestation. RESULTS: Mothers who had high carbohydrate intakes in early pregnancy had babies with lower placental and birth weights. Low maternal intakes of dairy and meat protein in late pregnancy were also associated with lower placental and birth weights. Placental weight fell by 49 g(95% confidence interval 16 g to 81 g; P=0.002) for each log g increase in intake of carbohydrate in early pregnancy and by 1.4 g (0.4 g to 2.4 g; P=0.005) for each g decrease in intake of dairy protein in late pregnancy. Birth weight fell by 165 g (49 g to 282 g; P=0.005) for each log g increase in carbohydrate intake in early pregnancy and by 3.1 g (0.3 g to 6.0 g; P=0.03) for each g decrease in meat protein intake in late pregnancy. These associations were independent of the mother's height and body mass index and of strong relations between the mother's birth weight and the placental and birth weights of her offspring. CONCLUSION: These findings suggest that a high carbohydrate intake in early pregnancy suppresses placental growth, especially if combined with a low dairy protein intake in late pregnancy. Such an effect could have long term consequences for the offspring's risk of cardiovascular disease.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Barker D. J., Bull A. R., Osmond C., Simmonds S. J. Fetal and placental size and risk of hypertension in adult life. BMJ. 1990 Aug 4;301(6746):259–262. doi: 10.1136/bmj.301.6746.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker D. J. Fetal origins of coronary heart disease. BMJ. 1995 Jul 15;311(6998):171–174. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.6998.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker D. J., Gluckman P. D., Robinson J. S. Conference report: fetal origins of adult disease--report of the First International Study Group, Sydney, 29-30 October 1994. Placenta. 1995 Apr;16(3):317–320. doi: 10.1016/0143-4004(95)90118-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block G., Woods M., Potosky A., Clifford C. Validation of a self-administered diet history questionnaire using multiple diet records. J Clin Epidemiol. 1990;43(12):1327–1335. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(90)90099-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emanuel I., Filakti H., Alberman E., Evans S. J. Intergenerational studies of human birthweight from the 1958 birth cohort. 1. Evidence for a multigenerational effect. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1992 Jan;99(1):67–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1992.tb14396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heap F. C., Lodge G. A., Lamming G. E. The influence of plane of nutrition in early pregnancy on the survival and development of embryos in the sow. J Reprod Fertil. 1967 Apr;13(2):269–279. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0130269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemminki E., Starfield B. Routine administration of iron and vitamins during pregnancy: review of controlled clinical trials. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1978 Jun;85(6):404–410. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1978.tb14905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe D. T., Wheeler T., Osmond C. The influence of maternal haemoglobin and ferritin on mid-pregnancy placental volume. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1995 Mar;102(3):213–219. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1995.tb09096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe D. Maternal haemoglobin and birth weight in different ethnic groups. Lower haemoglobin may be the result rather than the cause of larger fetuses. BMJ. 1995 Jun 17;310(6994):1601–1601. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6994.1601b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langley S. C., Jackson A. A. Increased systolic blood pressure in adult rats induced by fetal exposure to maternal low protein diets. Clin Sci (Lond) 1994 Feb;86(2):217–121. doi: 10.1042/cs0860217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margetts B. M., Cade J. E., Osmond C. Comparison of a food frequency questionnaire with a diet record. Int J Epidemiol. 1989 Dec;18(4):868–873. doi: 10.1093/ije/18.4.868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKEOWN T., RECORD R. G. The influence of placental size on foetal growth according to sex and order of birth. J Endocrinol. 1953 Nov;10(1):73–81. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0100073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKeigue P. Trans fatty acids and coronary heart disease: weighing the evidence against hardened fat. Lancet. 1995 Feb 4;345(8945):269–270. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90269-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]