Abstract

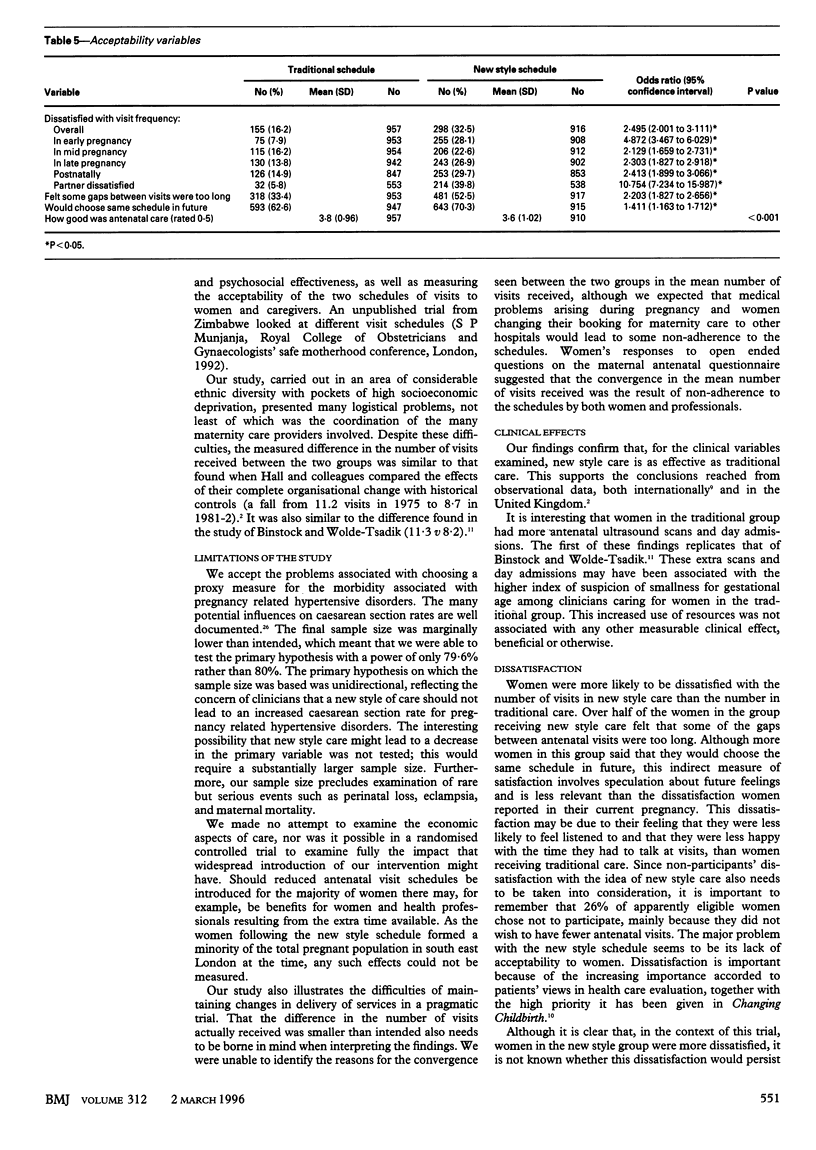

OBJECTIVE--To compare the clinical and psychological effectiveness of the traditional British antenatal visit schedule (traditional care) with a reduced schedule of visits (new style care) for low risk women, together with maternal and professional satisfaction with care. DESIGN--Randomised controlled trial. SETTING--Places in south east London providing antenatal care for women receiving shared care and planning to deliver in one of three hospitals or at home. SUBJECT--2794 women at low risk fulfilling the trial's inclusion criteria between June 1993 and July 1994. MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES--Measures of fetal and maternal morbidity, health service use, psychosocial outcomes, and maternal and professional satisfaction. RESULTS--Pregnant women allocated to new style care had fewer day admissions (0.8 v 1.0; P=0.002) and ultrasound scans (1.6 v 1.7; P=0.003) and were less often suspected of carrying fetuses that were small for gestational age (odds ratio 0.73; 95% confidence interval 0.54 to 0.99). They also had some poorer psychosocial outcomes; for example, they were more worried about fetal wellbeing antenatally and coping with the baby postnatally, and they had more negative attitudes to their babies, both in pregnancy and postnatally. These women were also more dissatisfied with the number of visits they received (odds ratio 2.50; 2.00 to 3.11). CONCLUSIONS--Patterns of antenatal care involving fewer routine visits for women at low risk may lead to reduced psychosocial effectiveness and dissatisfaction with frequency of visits. The number of antenatal day admissions and ultrasound scans performed may also be reduced. For the variables reported, the visit schedules studied are similar in their clinical effectiveness. Uncertainty remains as to the clinical effectiveness of reduced visit schedules for rare pregnancy problems.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Binstock M. A., Wolde-Tsadik G. Alternative prenatal care. Impact of reduced visit frequency, focused visits and continuity of care. J Reprod Med. 1995 Jul;40(7):507–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blondel B., Pusch D., Schmidt E. Some characteristics of antenatal care in 13 European countries. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1985 Jun;92(6):565–568. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1985.tb01393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitty L. S., Altman D. G., Henderson A., Campbell S. Charts of fetal size: 3. Abdominal measurements. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1994 Feb;101(2):125–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1994.tb13077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox J. L., Holden J. M., Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987 Jun;150:782–786. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davey D. A., MacGillivray I. The classification and definition of the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988 Apr;158(4):892–898. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(88)90090-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas K. A., Redman C. W. Eclampsia in the United Kingdom. BMJ. 1994 Nov 26;309(6966):1395–1400. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6966.1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall M. H., Chng P. K., MacGillivray I. Is routine antenatal care worth while? Lancet. 1980 Jul 12;2(8185):78–80. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(80)92950-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminski M., Blondel B., Bréart G. Management of pregnancy and childbirth in England and Wales and in France. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 1988 Jan;2(1):13–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.1988.tb00177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh G. N. New programme of antenatal care in general practice. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1985 Sep 7;291(6496):646–648. doi: 10.1136/bmj.291.6496.646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter M., Macintyre S. What is, must be best: a research note on conservative or deferential responses to antenatal care provision. Soc Sci Med. 1984;19(11):1197–1200. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(84)90370-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reading A. E., Cox D. N., Sledmere C. M., Campbell S. Psychological changes over the course of pregnancy: a study of attitudes toward the fetus/neonate. Health Psychol. 1984;3(3):211–221. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.3.3.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikorski J., Fleming J., Clement S. Rituals in antenatal care. Consider women's psychosocial needs. BMJ. 1993 Oct 23;307(6911):1064–1064. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6911.1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas P., Golding J., Peters T. J. Delayed antenatal care: does it effect pregnancy outcome? Soc Sci Med. 1991;32(6):715–723. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90151-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]