Abstract

Permanent neonatal diabetes mellitus (PNDM) is a rare disorder usually presenting within 6 months of birth. Although several genes have been linked to this disorder, in almost half the cases documented in Italy, the genetic cause remains unknown. Because the Akita mouse bearing a mutation in the Ins2 gene exhibits PNDM associated with pancreatic β cell apoptosis, we sequenced the human insulin gene in PNDM subjects with unidentified mutations. We discovered 7 heterozygous mutations in 10 unrelated probands. In 8 of these patients, insulin secretion was detectable at diabetes onset, but rapidly declined over time. When these mutant proinsulins were expressed in HEK293 cells, we observed defects in insulin protein folding and secretion. In these experiments, expression of the mutant proinsulins was also associated with increased Grp78 protein expression and XBP1 mRNA splicing, 2 markers of endoplasmic reticulum stress, and with increased apoptosis. Similarly transfected INS-1E insulinoma cells had diminished viability compared with those expressing WT proinsulin. In conclusion, we find that mutations in the insulin gene that promote proinsulin misfolding may cause PNDM.

Introduction

Neonatal diabetes is a rare monogenic disorder associated with defects of pancreatic β cell mass and/or function. The disorder is distinguished by 2 clinical variants — transient and permanent — caused by specific genetic defects. Abnormalities of chromosome 6 or mutations of the ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) channel KCNJ11 and ABCC8 genes are detected in most patients with transient neonatal diabetes mellitus (TNDM), in which diabetes usually presents in the first month of life but then remits with a variable time interval (1–4). In about 50% of patients with TNDM, diabetes relapses later in life (1–4). Permanent neonatal diabetes mellitus (PNDM) is more genetically heterogeneous and has been associated with mutations in 8 different genes: IPF-1, EIF2AK3, GCK, FOXP3, KCNJ11, PTF1A, ABCC8, and GLIS3 (4–11). Individuals with PNDM need insulin therapy, but those carrying mutations in KCNJ11 and ABCC8 can be successfully transferred to sulfonylureas (4, 12, 13). In most PNDM, diabetes manifests itself within the first 6 mo after birth, but delayed onset has been reported in subjects with mutations of EIF2AK3 (6, 14). PNDM can manifest itself as an isolated defect in glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (mutations of GCK, KCNJ11, and ABCC8; refs. 4, 7, 9) or as part of a syndrome involving other organ systems (4–6, 8–11, 15). Most patients (i.e., 40%–64%) with PNDM or infancy-onset diabetes bear dominant, activating, heterozygous mutations of KCNJ11, the pore-forming subunit of KATP channel (15), while activating mutations of its regulatory subunit SUR1 (ABCC8 gene) account for an additional 7% of cases (4). Other genetic defects leading to PNDM are much less common (5–8, 10, 11). We previously identified KCNJ11 mutations in 19 of 37 patients in an Italian cohort with diabetes onset by 7 mo of age (13, 16, 17), and we set about to search for the genetic causes of diabetes in the remaining subjects.

In one of these patients, kindred A, II-1, the C-peptide level at the time of diagnosis was surprisingly high, unlike the low C-peptide level in patients with PNDM caused by mutations of GCK, KCNJ11, and ABCC8 (4, 7, 9). High C-peptide immunoreactivity in the absence of apparent insulin resistance (18) has been identified in adult patients bearing point mutations in the proinsulin coding sequence leading to familial hyperproinsulinemia (19–21). Interestingly, a heterozygous mutation in the insulin-2 gene (Ins2) has previously been identified as the cause of early-onset diabetes in the Akita mouse (22), in which a Cys→Tyr substitution at proinsulin position 96 (C96Y; encoding residue 7 of the insulin A-chain) disrupts one of the 2 disulfide bonds connecting the insulin B- and A-chains. As a consequence, the Akita proinsulin accumulates in the ER, inducing ER stress and apoptosis of pancreatic β cells (22–25). We hypothesized that certain mutations of the human insulin gene (INS) might also give rise to neonatal diabetes mellitus. In this report we describe 7 proinsulin mutations, which we believe to be novel, associated with PNDM or infancy-onset diabetes mellitus that are likely to promote proinsulin misfolding, ER stress, and β cell failure.

Results

Mutational analysis.

We identified 7 heterozygous mutations of the INS gene in 10 unrelated probands with PNDM or infancy-onset diabetes. As would be expected for a defective gene specific to β cells, all affected neonates had only diabetes and no other clinical features. We adopted a nomenclature describing the mutations according to their position in the mature insulin chains: LB6P (that is, a Leu→Pro substitution at residue 6 of the insulin B-chain), LB6V, LB11P, LB15YB16delinsH (that is, replacement of Leu and Tyr by His at residues 15–16 of the B-chain), CA6Y, and YA19X. The proinsulin mutation located in the dibasic doublet between C-peptide and A-chain (K64–R65, based on the N-terminal Phe residue of the insulin B-chain as residue 1) is denoted as R65C. In all but 2 families, the mutation originated de novo, and neonatal diabetes was observed only in subjects carrying the INS gene mutation and not in unaffected parents. Mutation R65C was identified as a spontaneous mutation as well as in 2 familial cases (Figure 1). Mutation CA6Y was also detected in a Danish patient (diabetes onset, age 3 mo); however, DNA samples from 2 children of the proband, who presented with diabetes at 6.5 and 2.5 mo postpartum, were not available for analysis. All mutations found in patients with PNDM or infancy-onset diabetes were different from those previously described to lead to familial hyperinsulinemia or hyperproinsulinemia (19–21, 26–32). Notably, all affected residues — including CA6 (and CA11), LB6, LB11, and dibasic amino acids RR and KR, at the junctions between B-chain and C-peptide and between C-peptide and A-chain, respectively — are conserved among human, cow, pig, dog, rat, and mouse insulin I and II; between frog insulin I and II; and between eel and hagfish (33) (Supplemental Figure 1; supplemental material available online with this article; doi: 10.1172/JCI33777DS1). We did not detect these mutations in 200 Italian subjects with normal glucose tolerance.

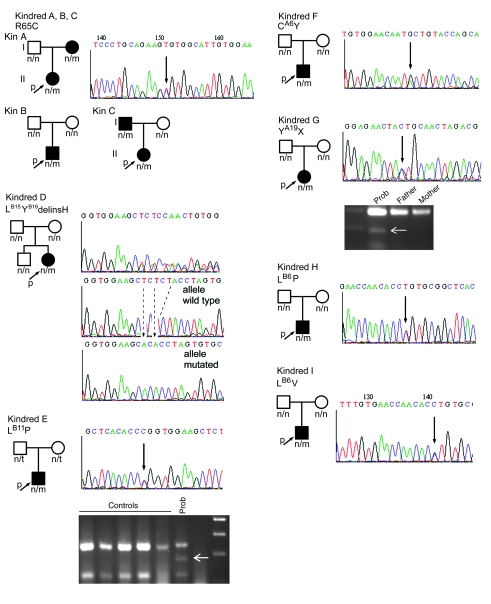

Figure 1. Family trees of patients carrying INS gene mutations.

Pherograms of the mutations are also shown, with mutations indicated by black arrows. The mutation causing diabetes in kindred D, LB15YB16delinsH, was determined by subcloning of the PCR product and DNA sequencing, confirmed in 10 clones. Mutations LB11P and YA19X, which respectively introduce HpaII and SpeI restriction sites, were both confirmed (white arrows) by RFLP-PCR. n, normal allele; m, mutant allele; p, proband. Patients carrying mutations are denoted by filled symbols.

Clinical characteristics.

All patients were the product of uneventful pregnancies; their clinical features at presentation of diabetes are shown in Table 1. In 3 subjects (kindreds E, G, and H), failure to thrive or intercurrent infection resulted in further analysis leading to a diagnosis of diabetes. In the case of patient II-1 of kindred A (mutation R65C), glycosuria was checked because the mother had been diagnosed with insulin-dependent diabetes at 1 yr of age and was found positive in the diaper at 76 d postpartum. Six patients (kindreds B, C, D, F, I, and PN-30) were referred to a local hospital for severe hyperglycemia with ketosis.

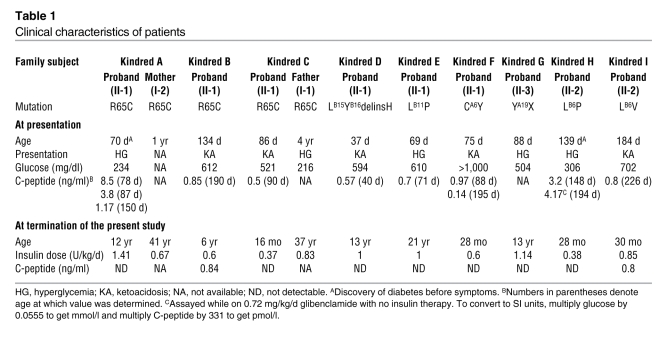

Table 1 .

Clinical characteristics of patients

C-peptide, randomly determined 1–56 d after discovery of diabetes and during the course of insulin therapy, was detected in 8 probands (data from 2 probands and 2 affected parents were not available). In 2 of these 8 probands, C-peptide appeared unexpectedly high (kindred A, II-1, and kindred H; Table 1). Furthermore, sequential assay of C-peptide in 2 patients on insulin therapy (kindred A, II-1, and kindred F) and in one on sulfonylurea for 60 d followed by mixed insulin-sulfonylurea therapy (kindred H) revealed declining values over the ensuing months after initial diagnosis. At the termination of the present study, C-peptide was undetectable in all but 3 patients. Basal pancreatic glucagon level was found to be in the normal to high range in 2 subjects (kindred A, I-1, 21.3 ng/dl; kindred D, 16.5 ng/dl), and glucagon secretion, as determined by an insulin tolerance test, increased approximately 50% as a result of insulin-induced hypoglycemia in both patients (kindred A, I-1, 30 ng/dl at 38 mg/dl plasma glucose; kindred D, 22 ng/dl at 34 mg/dl plasma glucose).

Clinical and metabolic features of PNDM or infancy-onset diabetes caused by INS gene mutations compared with those from other causes.

In all but 1 patient with an INS gene mutation (kindred F; Table 1), birth weight was near normal (median, 3,055 ± 227 g). This finding was in sharp contrast with the birth weight of patients with KCNJ11 mutations (median, 2,455 ± 370 g; P < 0.00021, INS versus KCNJ11). At the time of diagnosis, C-peptide was barely detectable in 4 of 10 KCNJ11 mutants of the Italian cohort (refs. 13, 16, and F. Barbetti, unpublished observations), whereas in patients for whom C-peptide data were available, measurable or even high C-peptide levels were found in all 8 individuals with INS mutations. The diagnosis of diabetes in patients with INS mutations occurred at 37–1,460 d postpartum (median, 88 ± 412.4 d), which is about 5 wk later than onset in patients with KCNJ11 mutations (range, 1–220 d; median, 53 ± 58.3 d; P < 0.07). With exclusion of 1 case (kindred C, I-1, 1,460 d), the comparison reached statistical significance (median, 87 ± 94.7 d; P < 0.00038). Indeed, individuals with INS gene mutation can present with diabetes well beyond 6 mo after birth (F. Barbetti, unpublished observations). This feature is also found in patients with EIF2AK3 mutations (Wolcott-Rallison syndrome), which disrupt the normal ER stress response and cause dysregulated secretory protein synthesis in pancreatic β cells (6, 14). Finally, because most INS gene mutations occur spontaneously, these patients cannot be distinguished on clinical grounds from those with type 1 diabetes (besides the absence of type 1 diabetes autoantibodies). For this reason we propose here to replace the term PNDM with monogenic diabetes of infancy (MDI), a broad definition that may include any form of diabetes — permanent or transient — with onset during the first years of life caused by a single gene defect.

Functional studies.

Figure 2 shows the location of the mutated residues. Two mutations each affect 1 of the 3 highly conserved insulin disulfide bonds, similar to that reported in the Akita mouse: CA6Y perturbs CA6–CA11, while YA19X disrupts CB19–CA20 by generating a premature stop codon that eliminates CA20 as well as NA21 at the C terminus. Another mutation is an in-frame substitution in which B-chain Leu15 and Tyr16 are replaced by a single His residue: LB15YB16delinsH. In 3 additional cases, proinsulin mutations were located in invariant residues of the B-chain (LB6P, LB6V, and LB11P; Supplemental Figure 1). Of these, LB6P and LB11P are located in the so-called “hydrophobic core” on the contact surface buried within insulin dimers. The mutations predicted to most dramatically affect proinsulin secondary structure included LB15YB16delinsH (by causing significant α-helix disruption; Figure 3) and R65C (by abolishing the C-peptide/A-chain cleavage site while creating an unpaired Cys residue with potential to form inappropriate disulfide bonds).

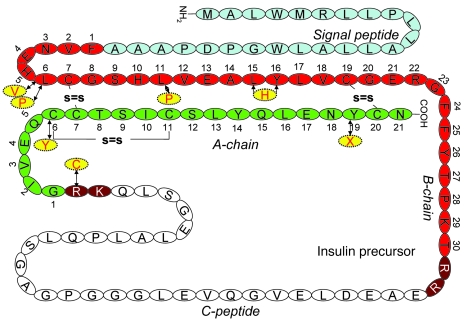

Figure 2. Amino acid sequences of WT and mutant proinsulins.

The amino acid sequence and disulfide bonds (s=s) of WT proinsulin are shown. Amino acid substitutions associated with PNDM/MDI are shown in yellow.

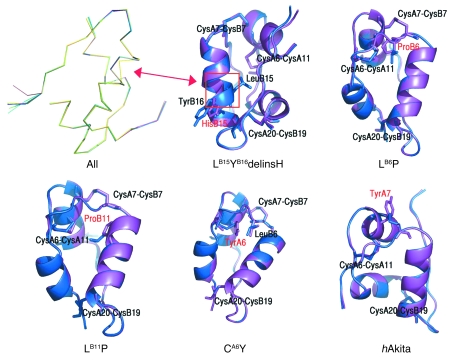

Figure 3. Secondary structure computer modeling of WT and mutant proinsulins.

Shown are superimposed Cα traces of WT (blue) and all mutated insulins (purple), with the exception of LB6V. The positions of disulfide bridges are also marked. None of the mutations caused substantial distortion of the secondary structure, with the exception of LB15YB16delinsH (yellow trace at left), where an α-helical disruption is apparent (arrow). This was also evident in the superimposition of WT insulin and LB15YB16delinsH. The LB6P mutation alters the hydrophobic core of the protein. The LB11P mutation affects the hydrophobic core of the protein. The CA6Y mutation disrupts the A6–A11 disulfide bridge; the tyrosine is oriented inside the hydrophobic core of the protein, where it engages LB6 in a stacking interaction. The hAkita mutation — used in this study as positive control — disrupts the B7–A7 disulfide bridge, and the tyrosine is solvent exposed.

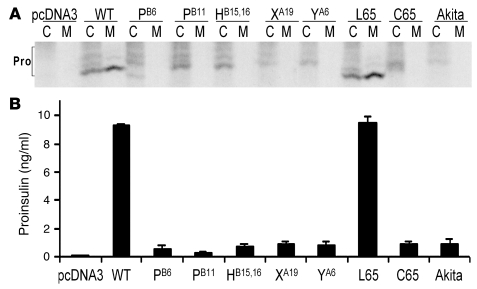

In 3 independent experiments, all proinsulin mutants except LB6V were expressed as recombinant proteins in HEK293 cells and examined for 35S-protein expression and secretion at 1 h after synthesis (Figure 4A). After immunoprecipitation from cells and analysis by nonreducing Tris-tricine-urea-SDS-PAGE, WT proinsulin and proinsulin-R65L (a hyperproinsulinemia-inducing mutation associated with mild fasting hyperglycemia in an adult patient; ref. 19) were well expressed, with similar fractions of fast-migrating native proinsulin disulfide isomer and slower-migrating nonnative forms (34). Within 1 h of synthesis, both WT proinsulin and the R65L mutant underwent efficient secretion to the culture media. However, all MDI-causing mutations and the Akita mutation introduced into human proinsulin (hAkita; mutation CA7Y) exhibited substantially decreased recovery with an increased fraction of nonnative proinsulin disulfide isomers and a profound decrease in secretion (Figure 4A). In a separate set of experiments, proinsulin mutants that were not secreted appeared to be degraded intracellularly (data not shown). As an independent assay, proinsulin released into serum-free culture media was detected by RIA (Figure 4B), confirming defective secretion for all MDI-producing proinsulin mutants. These data establish that MDI-producing proinsulin mutations perturb proinsulin structure and lead to defective secretion.

Figure 4. Misfolding and defective secretion of proinsulin mutants.

293T cells were transfected with empty vector or cDNAs encoding WT proinsulin or the following proinsulin mutants: LB6P (PB6); LB11P (PB11); LB15YB16delinsH (HB15,16); YA19X (XA19); CA6Y (YA6); R65L (L65); R65C (C65); and hAkita. (A) Transfected cells were metabolically labeled with 35S–amino acids for 1 h and then further chased for 1 h. Cell lysates (C) and chase media (M) were immunoprecipitated with anti-insulin, and the samples were analyzed by nonreducing Tris-tricine-urea-SDS-PAGE. All proinsulin (Pro) disulfide isomers demonstrated different mobilities; the native form is the fast-migrating, secreted form obtained for WT proinsulin. (B) Recombinant proinsulin secreted for 16 h into serum-free medium was quantified by RIA.

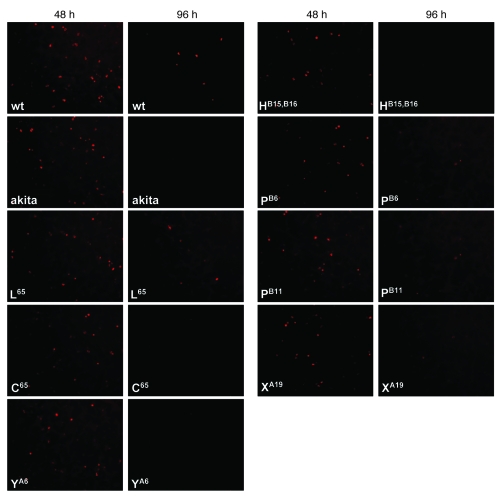

Next, WT proinsulin, the R65L mutant, the hAkita mutation, and all new MDI-associated mutations except LB6V were expressed as recombinant human proinsulins in INS-1E rat insulinoma cells, which are capable of processing proinsulin into insulin and C-peptide. The recombinant proinsulins were readily detected by immunofluorescence with a human-specific anti-proinsulin antibody at 48 h after transfection (Figure 5). However, at 96 h after transfection, immunofluorescence was still detectable in 61% ± 2.8% of INS-1E cells transfected with WT proinsulin (n = 4 transfections) and 56% ± 4.0% of cells transfected with the R65L mutation (n = 3 transfections), but almost none was detected in cells transfected with the hAkita mutation or with R65C, LB15YB16delinsH, CA6Y, or YA19X (mean, 3 transfections each). An intermediate percentage of viable INS-1E cells at 96 h was observed for mutations LB6P (36% ± 2.2%; n = 2 transfections) and LB11P (17.7% ± 4.8%; n = 5 transfections).

Figure 5. Viability of transfected INS-1E cells.

Shown is the viability of INS-1E cells at 48 and 96 h after transfection with WT human (pro)insulin, hAkita mutation, human familial hyper(pro)insulinemia mutation R65L, and human MDI mutations R65C, CA6Y, LB15YB16delinsH, LB6P, LB11P, and YA19X. Human (pro)insulin was detected by monoclonal antibody directed toward the human C-peptide and C terminus of the B-chain of the (pro)insulin molecule. Few (LB6P and LB11P) or no (hAkita, R65C, CA6Y, LB15YB16delinsH, and YA19X) INS-1E cells expressing MDI mutations were visible 96 h after transfection.

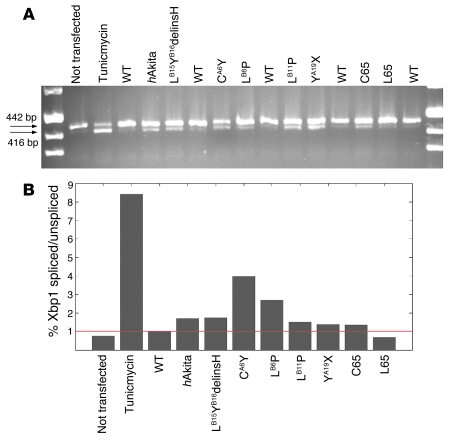

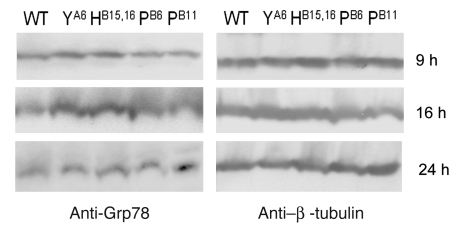

The same constructs tested by immunofluorescence were used to evaluate XBP1 gene splicing, a marker of ER stress. Tunicamycin (5 μg/ml for 4 h), a general inducer of ER stress, was used as positive control. As seen in Figure 6A, no difference was detected between untransfected cells and those transfected with WT proinsulin or the R65L mutation. In contrast, recombinant human proinsulins containing MDI-associated mutations (including LB6P; data not shown) and the hAkita mutation induced increases of the shorter, splice-activated form of XBP1 from 30% (R65C and YA19X) to 400% (CA6Y) (Figure 6B). We then tested protein expression of chaperonin Grp78, also known as BiP, as an additional marker of ER stress. As shown in Figure 7, Grp78 protein amounts increased in 293 cells 9 and 16 h after transfection with CA6Y and LB15YB16delinsH mutant proinsulins compared with WT proinsulin; higher levels of Grp78 were observed at 24 h after transfection for mutations LB6P and LB11P.

Figure 6. XBP1 splicing in transfected HEK293 cells.

(A and B) Splicing of transcription factor XBP1 by agarose gel (A) and densitometry (B). Shown is the percentage of spliced/unspliced XBP1 forms for each sample, as assessed by densitometry, relative to WT. The red line indicates ratio 1. All mutations associated with PNDM or infancy-onset diabetes (and hAkita) induced an increase in XBP1 splicing compared with WT (pro)insulin or familial hyper(pro)insulinemia mutation R65L.

Figure 7. Grp78 expression.

Western blot with anti-Grp78 primary antibody in HEK293 cells transfected with WT and mutated insulin. Cytoplasmic fractions were collected at 9, 16, and 24 h after transfection. Expression of β-tubulin was assessed on the same filters to normalize the amount of loaded proteins. Increased Grp78 protein expression was clearly visible at 9 and 16 h for mutations LB15YB16delinsH and CA6Y and at 24 h for mutations LB6P and LB11P.

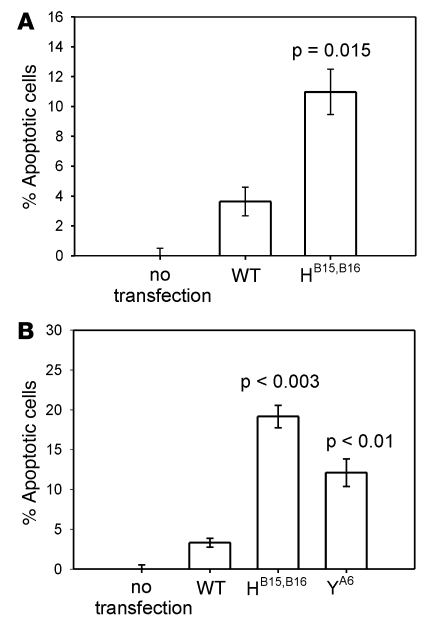

As an early apoptosis marker, we assessed surface staining of annexin V. In 3 independent flow cytometry experiments at 24 h after transfection of HEK293 cells, we detected a 4-fold increase of annexin V positivity in cells expressing proinsulin LB15YB16delinsH compared with cells expressing WT proinsulin (P = 0.015; Figure 8A). However, using this technique, we were unable to observe effects with other MDI mutations or even the hAkita mutation. As a late apoptosis marker, we evaluated by flow cytometry the percentage of propidium iodide–positive cells at 24, 48, and 72 h after transfection (Figure 8B). With this assay, we detected increased numbers of apoptotic 293 cells transfected with the LB15YB16delinsH and the CA6Y mutations at 24 h after transfection compared with WT proinsulin (P < 0.003 and P < 0.01, respectively), but for the remaining MDI mutations we did not find any change at all points tested. Taken together, these data suggest that at least some of the proinsulin mutants, in addition to being defective in insulin production (loss of function), might also compromise β cell viability (toxic gain of function).

Figure 8. Annexin V expression and propidium iodide assay.

(A) Percentage of apoptotic cells, as assessed by annexin V expression, in HEK293 cells transfected with human WT (pro)insulin or LB15YB16delinsH mutation. Expression of mutant (pro)insulin effected a 3-fold increase in annexin V–positive cells 24 h after transfection compared with cells transfected with WT (pro)insulin. (B) Percentage of propidium iodide–positive cells transfected with WT, LB15YB16delinsH, and CA6Y mutation cDNA. P values are shown compared with WT (pro)insulin.

Discussion

Previously, abnormal circulating proinsulin had been reported in subjects with elevated plasma levels of immunoreactive insulin but normal insulin sensitivity (19, 21, 27, 28, 30). Such patients with familial hyperproinsulinemia are diagnosed as adults with mild diabetes, impaired glucose tolerance (19–21, 27, 28, 30, 32), or even episodic hypoglycemia (26, 31). Mutations of the human INS gene causing familial hyperinsulinemia or familial hyperproinsulinemia encode defects either in insulin receptor binding (FB25L, FB24S, VA3L; Insulin Chicago, Los Angeles, and Wakayama; refs. 27, 28, 30) or in the dibasic C-peptide/A-chain cleavage site (R65H, R65L, R65P; Proinsulin Tokyo and Kyoto; refs. 19–21, 31, 32), with the exception of the HB10D mutant (Proinsulin Providence) that may affect insulin packaging (29). However, in familial hyperproinsulinemia, the abnormal INS gene product is efficiently secreted. In addition, no INS coding sequence polymorphisms have been found associated with type 2 diabetes (35, 36).

In this study we describe what we believe to be new heterozygous mutations within the proinsulin coding sequence causing early-onset, insulin-requiring diabetes (2–48 mo postpartum). In the Italian patient cohort with PNDM, mutations of the INS gene were the second leading cause (9 of 37, or 24.3%) following activating mutations of KCNJ11 (19 of 37, or 51.3%). Spontaneous mutations in a small gene are unlikely to be a chance observation (9), yet in 7 patients the mutations arose de novo. We also describe 2 familial cases with vertical transmission of insulin-requiring diabetes. In 2 patients (kindred A, II-1, and kindred H) in which hyperglycemia was detected before severe diabetes symptoms, C-peptide was found at normal to high levels, but was decreased or undetecable within 2–12 mo of diagnosis. The INS gene mutations described herein are highly reminiscent of the diabetes phenotype observed in male Akita mice, in which a heterozygous mutation of the Ins2 gene (CA7Y, disrupting an interchain disulfide bond of insulin) causes a doubling of plasma glucose within 4 wk of birth (37) with a rapid decrease of pancreatic β cells (22). A proposed molecular pathogenesis of diabetes in the Akita mutant is (a) proteotoxic proinsulin misfolding, (b) engorgement of the β cell ER with activation of ER stress response pathways, and (c) generation of downstream apoptotic signals (22–25). The β cell deficiency in male Akita mice stands in striking contrast with the finding that Ins1–/–Ins2–/– mice, which lack all insulin and die of neonatal diabetes, actually show hyperplastic pancreatic islets (38).

The translational studies described herein support the hypothesis that all of the new INS gene mutations reported in patients with PNDM/MDI cause proinsulin misfolding. Two mutants described in this report, CA6Y and YA19X, directly lack 1 of the 3 stabilizing disulfide bonds of proinsulin (39), while the mutants LB6P, LB6V, LB11P, and LB15YB16delinsH involve less obvious structural distortions. The clinical phenotype of the patient carrying the YA19X mutation (diabetes onset at age 88 d) seems to indicate that the mutant protein is translated and that the mRNA decay usually associated with a premature stop codon is not involved. Further evidence for proinsulin misfolding comes from an increased ER stress response (Figure 6). Moreover, examination of R65C, found in 3 independent probands, as well as YA19X and CA6Y, like the Akita mutant (Figure 4), revealed the presence of improper disulfide bonds with little or no secretion, consistent with entrapment within the ER. The direct demonstration of cell death induced by expression of at least 2 of the mutants (Figure 8) strongly supports a proteotoxic, apoptotic mechanism.

Of the patients described herein, 9 of 10 showed normal weight at birth, a finding clearly different from the low birth weight in patients bearing KCNJ11 mutations (15), which suggests that β cell insufficiency may occur primarily after birth. Pancreatic β cell proliferation is low in humans after birth (40). A postpartum decline in measurable C-peptide, taken together with other results presented herein, support the hypothesis that postnatal failure to maintain β cell mass due to proteotoxic proinsulin misfolding is a primary cause of PNDM in these patients with INS gene mutations. We are not able at this stage of our study to explain why the parents of familial cases with the R65C mutation were diagnosed with diabetes at 1 and 4 yr of age, while 2 probands with the same mutation presented with diabetic ketoacidosis at 86 and 134 d after birth. However, this result indicates that such rare patients with INS gene mutants are likely to be hidden within the larger population of those diagnosed with type 1 diabetes. Finally, we advocate the concept of substituting the term MDI for PNDM (41), reflecting our awareness that onset of hyperglycemia in monogenic forms of diabetes extends beyond the neonatal period (refs. 6, 9, 15, and the present study).

Methods

Subjects.

The Early Onset Diabetes Study Group of the Italian Society of Pediatric Endocrinology and Diabetes (SIEDP) has been studying 37 patients who had diabetes onset within the first 220 d of life and are negative for type 1 diabetes autoantibodies. Of these probands, we detected activating heterozygous mutations of KCNJ11 in 19 subjects (refs. 13, 16, 17, and C. Colombo and F. Barbetti, unpublished observations) and a homozygous inactivating mutation of GCK in a single case (7). We screened the remaining 17 patients for mutations in the coding region of the INS gene and genotyped the parents of each proband with an INS mutation. The INS gene was also examined in 2 additional patients from Denmark with infancy-onset diabetes. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants or their parents. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Early Onset Diabetes Study Group of the SIEDP.

Clinical studies.

We compared the clinical features of the patients carrying mutations of the INS gene with those of patients from our case series carrying a KCNJ11 mutation. An insulin tolerance test was performed by injecting 0.1 IU/kg BW i.v. of regular insulin. Blood samples were withdrawn at –15, 0, 15, 30, and 45 min relative to the time of insulin injection for determination of plasma glucose, pancreatic glucagon (Linco), growth hormone, and cortisol.

Functional studies.

Insulin cDNA was kindly provided by H. Lou (NIH, Bethesda, Maryland, USA). Full-length insulin cDNA was amplified by PCR using the following primers containing HindIII or EcoRI restriction sites: Ins-Hind, 5′-CCTAGTTGAGAAGCTTGTCCTTCTGCCATGGCCCTG-3′; Ins-Eco, 5′-CCTAGTTGAGGAATTCTCCATCTCTCTCGGTGCAGG-3′. Amplification product was digested with EcoRI and HindIII, run on 1% agarose gel, purified using QIAquick Gel Extraction kit (Qiagen), and cloned into pCDNA3.1+ expression vector (Invitrogen). Exon 2 of insulin LB15YB16delinsH was directly cloned after PCR amplification in pCRII-TOPO vector of the TOPO TA cloning system (Invitrogen). All newly described mutations, with the exception of LB6V, as well as control mutations R65L and hAkita (22) were introduced by site-directed mutagenesis of the human proinsulin cDNA using QuickChangeII Site directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) following the manufacturer’s protocol.

INS-1E cells (gift of C. Wollheim, University Medical Centre, Geneva, Switzerland) were cultured in RPMI (Invitrogen) supplemented with 2 mM l-glutamine, 10 mM HEPES, 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol, 10% FBS, 100 IU/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin in a 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37°C. INS-1E cells (80% confluent) were transfected transiently using Lipofectamine (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Expression of WT proinsulin and each new proinsulin mutant (with the exception of LB6V) plus control proinsulin-R65L and hAkita mutants were visualized at 48 and 96 h after transfection by immunofluorescence using monoclonal antibody to human proinsulin (1:300 dilution; Abcam) and Alexa Fluor 594 goat anti-mouse (1:500 dilution; Invitrogen). Monoclonal antibody to human proinsulin has no cross-reactivity with either rat proinsulin 1 or rat proinsulin 2. Transfected cells were visualized by immunofluorescence after the following procedure: cells were washed with PBS, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min, washed quickly in PBS, permeabilized in PBS plus 0.2% Triton X-100 for 15 min, blocked in PBS plus 10% FBS for 30 min, incubated with primary antibody for 1 h at 37°C, washed 3 times with PBS plus 0.5% Tween, incubated with secondary antibody for 1 h at 37°C, washed 3 times with PBS plus 0.5% Tween, and mounted with 50% glycerol. Insulin-expressing cells were visualized with a Nikon TE2000-E Eclipse fluorescence microscope and counted along 2 diameters of each well.

XBP1 splicing.

HEK293T cells were transfected with WT or mutant INS cDNA. At 2 d after transfection, RNA was extracted and retrotranscribed, and 50 ng was used for PCR amplification of XBP1. Amplified fragments were resolved by agarose gel electrophoresis and scanning densitometry.

Grp78 protein expression.

HEK293T cells’ cytoplasmic proteins were extracted in lysis buffer (containing 0.5% Triton X, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF, 4 mg/ml aprotinin, and 2 μg/ml pepstatin) at 9, 16, and 24 h after transfection with WT or mutant INS cDNA, after which they were loaded on SDS-PAGE gels at 10% and electroblotted. Filters were decorated with anti-Grp78 antibody (catalog no. PA1-41051, 1:1,000 dilution; Affinity Bioreagents) followed by a peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody for enhanced chemiluminescence. Anti-human β-tubulin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.) was used at 1:1,000 dilution with the same secondary antibody.

Biosynthesis of WT proinsuiln and mutations R65L, R65C, LB6P, LB11P, LB15YB16delinsH, CA6Y, YA19X, and hAkita.

Transfected HEK293T cells were preincubated in Met/Cys-deficient DMEM, pulse-labeled with 35S–amino acids, and then chased in complete media. Transfected cells were lysed in 0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 0.2% deoxycholate, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM EDTA, and 25 mM Tris, pH 7.4, plus a proteinase inhibitor cocktail. Lysed cells and chase media were subjected to immunoprecipitation with guinea pig anti-insulin, and samples were analyzed by Tris-tricine-urea-SDS-PAGE as described previously (33). To quantify proinsulin secretion, at 40 h after transfection cells were washed and then further incubated for 16 h in serum-free DMEM containing 25.5 mM glucose plus 0.2 % bovine serum albumin (RIA-grade). The incubation media were collected, and aliquots were taken to measure total immunoreactivity of insulin-containing peptides (i.e., proinsulin) using an anti-rat insulin RIA (Millipore) that reacts with WT and mutant proinsulins.

Apoptosis assays.

HEK293 cells were seeded in a 24-well plate (150,000 cells/well) 24 h before transfection. Cells at 50%–60% confluence were transiently transfected with 800 ng plasmid containing WT proinsulin, a proinsulin mutant (with the exception of LB6V), human familial hyper(pro)insulinemia R65L, or hAkita. To assay annexin V surface staining, adherent cells at 24 and 48 h after transfection were recovered by trypsinization and collected with complete DMEM. Each culture medium was collected and added to the corresponding sample in order to count detached cells. The annexin V assay (Calbiochem) was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The number of apoptotic cells was measured by FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson). In the propidium iodide assay, cells were similarly recovered by trypsinization, fixed with 70% cold ethanol, treated with RNase, and stained with 20 ng/ml propidium iodide. The number of apoptotic cells was measured by flow cytometry as described above. The percentage of apoptosis in untransfected, control HEK293 cells (4%, mean of 5 experiments) was subtracted from the percentage of apoptotic cells observed in transfections with WT or mutant (pro)insulins.

Modeling.

Computer modeling of the structures of human WT and mutant insulins were generated by homology to bovine insulin as a template using Modeller software version 8.1 ( http://www.salilab.org/modeller/). Ramachandran plots of the models indicated that there were no residues in disallowed regions.

Statistics.

Values are expressed as mean ± SEM. A 2-tailed Student’s t test was used for all statistical analysis. P values less than 0.03 were considered significant.

Note added in proof.

Since submission of this report, 4 papers have been published describing INS gene mutations associated with PNDM (42–45).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all the families who participated in this study. P. Arvan’s laboratory was supported by NIH grant R01-DK48280.

Footnotes

Nonstandard abbreviations used: hAkita, Akita mutation introduced into human proinsulin; MDI, monogenic diabetes of infancy; PNDM, permanent neonatal diabetes mellitus; TNDM, transient neonatal diabetes mellitus.

Conflict of interest: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Citation for this article: J. Clin. Invest. 118:2148–2156 (2008). doi:10.1172/JCI33777

References

- 1.Polak M., Shield J. Neonatal and very-early-onset diabetes mellitus. Semin. Neonatol. 2004;9:59–65. doi: 10.1016/S1084-2756(03)00064-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gloyn A.L., et al. Relapsing diabetes can result from moderately activating mutations in KCNJ11. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2005;14:925–934. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Colombo C., et al. Transient neonatal diabetes mellitus is associated with a recurrent (R201H) KCNJ11 (KIR6.2) mutation. . Diabetologia. 2005;48:2439–2441. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-1958-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Babenko A.P., et al. Activating mutations in the ABCC8 gene in neonatal diabetes mellitus. . N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;355:456–466. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stoffers D.A., Zinkin N.T., Stanojevic V., Clarke W.L., Habener J.F. Pancreatic agenesis attributable to a single nucleotide deletion in the human IPF1 gene coding sequence. Nat. Genet. 1997;15:106–110. doi: 10.1038/ng0197-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Delepine M., et al. EIF2AK3, encoding translation initiation factor 2-α kinase 3, is mutated in patients with Wolcott-Rallison syndrome. Nat. Genet. 2000;25:406–409. doi: 10.1038/78085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Njolstad P.R., et al. Neonatal diabetes mellitus due to complete glucokinase deficiency. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001;344:1588–1592. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105243442104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bennet C.L., et al. The immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked syndrome (IPEX) is caused by mutations of FOXP3. Nat. Genet. 2001;27:20–21. doi: 10.1038/83713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gloyn A.L., et al. Activating mutations in the ATP-sensitive potassium channel subunit Kir6.2 gene are associated with permanent neonatal diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004;350:1838–1849. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sellick G.S., et al. Mutations in PTF1A cause pancreatic and cerebellar agenesis. Nat. Genet. 2004;36:1301–1305. doi: 10.1038/ng1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Senee V., et al. Mutations in GLIS3 are responsible for a rare syndrome with neonatal diabetes mellitus and congenital hypothyroidism. Nat. Genet. 2006;38:682–687. doi: 10.1038/ng1802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pearson E.R., et al. Switching from insulin to oral sulfonylureas in patients with diabetes due to Kir6.2 mutations. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;355:467–477. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tonini G., et al. Sulphonylurea treatment outweighs insulin therapy in short-term metabolic control of patients with permanent neonatal diabetes mellitus due to activating mutations of the KCNJ11 (Kir6.2) gene. . Diabetologia. 2006;49:2210–2213. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0329-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seneé V., et al. Wolcott-Rallison syndrome. Clinical, genetic and functional study of EIF2AK3 mutations and suggestion of genetic heterogeneity. Diabetes. 2004;53:1876–1883. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.7.1876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hattersley A.T., Ashcroft F.M. Activating mutations in Kir6.2 and neonatal diabetes. New clinical syndromes, new scientific insights, and new therapy. Diabetes. 2005;54:2503–2513. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.9.2503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Massa O., et al. KCNJ11 activating mutations in Italian patients with permanent neonatal diabetes. Hum. Mutat. 2005;25:22–27. doi: 10.1002/humu.20124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Masia R., et al. An ATP-binding mutation (G334D) in KCNJ11 is associated with a sulfonylurea-insensitive form of developmental delay, epilepsy, and neonatal diabetes. Diabetes. 2007;56:328–336. doi: 10.2337/db06-1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taylor S.I., et al. Mutations in the insulin receptor gene. Endocr. Rev. 1992;13:566–595. doi: 10.1210/er.13.3.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yano H., et al. A novel point mutation in the human insulin gene giving rise to hyperproinsulinemia (Proinsulin Kyoto). J. Clin. Invest. 1992;89:1902–1907. doi: 10.1172/JCI115795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakashima N., Sakamoto N., Umeda F., et al. Point mutation in a family with hyperproinsulinemia detected by single stranded conformational polymorphism. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1993;76:633–636. doi: 10.1210/jc.76.3.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oohashi H., et al. Familial hyperproinsulinemia associated with NIDDM. A case study. Diabetes Care. 1993;16:1340–1346. doi: 10.2337/diacare.16.10.1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang J., et al. A mutation in the insulin 2 gene induces diabetes with severe pancreatic β-cell dysfunction in the Mody mouse. . J. Clin. Invest. 1999;103:27–37. doi: 10.1172/JCI4431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zuber C., Fan J.-Y., Guhl B., Roth J. Misfolded proinsulin accumulates in expanded pre-Golgi intermediates and endoplsmic reticulum subdomains in pancreatic beta cell of Akita mice. FASEB J. 2004;18:917–919. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1210fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oyadomari S., et al. Targeted disruption of the Chop gene delays endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated diabetes. J. Clin. Invest. 2002;109:525–532. doi: 10.1172/JCI14550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ron D. Proteotoxicity in the endoplasmic reticulum: lessons from the Akita diabetic mouse. J. Clin. Invest. 2002;109:443–445. doi: 10.1172/JCI15020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gabbay K.H., DeLuca K., Fisher J.N., Mako M.E., Rubenstein A.H. Familial hyperproinsulinemia. An autosomal dominant defect. N. Engl. J. Med. 1976;294:911–915. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197604222941701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Given B.D., et al. Diabetes due to secretion of an abnormal insulin. N. Engl. J. Med. 1980;302:129–135. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198001173020301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haneda M., et al. Familial hyperinsulinemia due to a structurally abnormal insulin. Definition of an emerging new clinical syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 1984;310:1288–1294. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198405173102004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gruppuso P.A., et al. Familial hyperproinsulinemia due to a proposed defect in conversion of proinsulin to insulin. N. Engl. J. Med. 1984;311:629–634. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198409063111003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nanjo K., et al. Diabetes due to secretion of a structurally abnormal insulin (insulin Wakayama). Clinical and functional characteristics of [LeuA3] insulin. J. Clin. Invest. 1986;77:514–519. doi: 10.1172/JCI112331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barbetti F., et al. Two unrelated patients with familial hyperproinsulinemia due to a mutation substituting histidine for arginine at position 65 in the proinsulin molecule: identification of the mutation by direct sequencing of genomic DNA amplified by polymerase chain reaction. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1990;71:164–169. doi: 10.1210/jcem-71-1-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Warren-Perry M.G., et al. A novel point mutation in the insulin gene giving rise to hyperproinsulinemia. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1997;82:1629–1631. doi: 10.1210/jc.82.5.1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Shuldiner, A.R., Barbetti, F., Raben, R., Scavo, L., and Serrano, J. 1990. Insulin.In Insulin-like growth factors:molecular and cellular aspects . D. LeRoith, editor. CRC Press. Boca Raton, Florida, USA. 181–219. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu M., Li Y., Cavener D., Arvan P. Proinsulin disulfide maturation and misfolding in the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:13209–13212. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400475200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raben N., et al. Normal coding sequence of insulin gene in Pima Indians and Nauruans, two groups with highest prevalence of type II diabetes. Diabetes. 1991;40:118–122. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.40.1.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Olansky L., Janssen R., Welling C., Permutt M.A. Variability of the insulin gene in American blacks with NIDDM. Analysis by single-strand conformational polymorphisms. Diabetes. 1992;41:742–749. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.41.6.742b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yoshioka M., Kayo T., Ikeda T., Koizumi A. A novel locus, Mody4, distal to D7Mit189 on chromosome 7 determines early-onset NIDDM in nonobese C57BL/6 (Akita) mutant mice. Diabetes. 1997;46:887–894. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.46.5.887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Duvillie B., et al. Phenotypic alterations in insulin-deficient mutant mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1997;94:5137–5140. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rhodes, C.J. 2004. Processing of the insulin molecule. InDiabetes Mellitus. A fundamental and clinical text. 3rd edition. D. LeRoith, S.I. Taylor, and J.M. Olefsky, editors. Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA. 27–50. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kassem S.A., Ariel I., Thornton P.S., Scheimberg I., Glaser B. Beta-cell proliferation and apoptosis in the developing normal human pancreas and in hyperinsulinism of infancy. Diabetes. 2000;49:1325–1333. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.8.1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barbetti F. Diagnosis of neonatal and infancy-onset diabetes. Endocr. Dev. 2007;11:83–93. doi: 10.1159/000111060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Støy J., et al. Insulin gene mutations as a cause of permanent neonatal diabetes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. . 2007;104:15040–15044. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707291104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Edghill E.L., et al. Insulin mutation screening in 1,044 patients with diabetes: mutations in the INS gene are a common cause of neonatal diabetes but a rare cause of diabetes diagnosed in childhood or adulthood. Diabetes. 2008;57:1034–1042. doi: 10.2337/db07-1405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Polak M., et al. Heterozygous missense mutations in the insulin gene are linked to permanent diabetes appearing in the neonatal period or in early infancy: a report from the French ND (Neonatal Diabetes) Study Group. Diabetes. 2008;57:1115–1119. doi: 10.2337/db07-1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Molven A., et al. 2008Mutations in the insulin gene can cause MODY and autoantibody-negative type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 571131. – 1135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.