Abstract

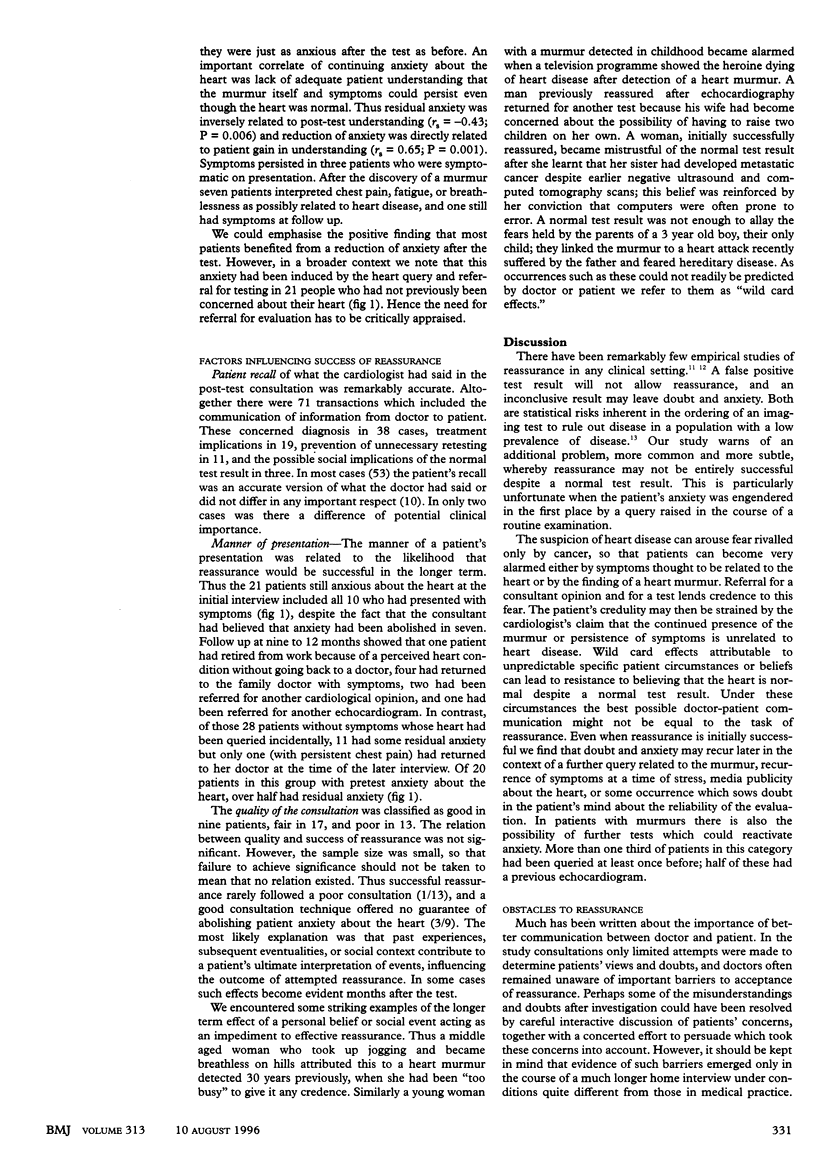

OBJECTIVES--To determine the rate of failure of patient reassurance after a normal test result and study the determinants of failure. DESIGN--Replicated single case study with qualitative and quantitative data analysis. SETTING--University teaching hospital. SUBJECTS--40 consecutive patients referred for echocardiography either because of symptoms (10 patients) or because of a heart murmur (30). 39 were shown to have a normal heart. INTERVENTIONS--Medical consultations and semistructured patient interviews were tape recorded. Structured interviews with consultant cardiologists were recorded in survey form. MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES--Patient recall of the explanation and residual understanding, doubt, and anxiety about the heart after the test and post-test consultation. RESULTS--All 10 patients presenting with symptoms were left with anxiety about the heart despite a normal test result and reassurance by the consultant. Of 28 patients referred because of a murmur but shown to have no heart abnormality, 20 became anxious after detection of the murmur; 11 had residual anxiety despite the normal test result. CONCLUSIONS--Reassurance of the "worried well"-anxious patients with symptoms or patients concerned by a health query resulting from a routine medical examination or from screening-constitutes a large part of medical practice. It seems to be widely assumed that explaining that tests have shown no abnormality is enough to reassure. The results of this study refute this and emphasise the importance of personal and social factors as obstacles to reassurance.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Feinstein A. R. An additional basic science for clinical medicine: II. The limitations of randomized trials. Ann Intern Med. 1983 Oct;99(4):544–550. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-99-4-544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick R., Hopkins A. Referrals to neurologists for headaches not due to structural disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1981 Dec;44(12):1061–1067. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.44.12.1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt L. M., Jordan B., Irwin S. Views of what's wrong: diagnosis and patients' concepts of illness. Soc Sci Med. 1989;28(9):945–956. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(89)90324-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer M. S., Feinstein A. R. Clinical biostatistics. LIV. The biostatistics of concordance. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981 Jan;29(1):111–123. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1981.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald I. G., Guyatt G. H., Gutman J. M., Jelinek V. M., Fox P., Daly J. The contribution of a non-invasive test to clinical care. The impact of echocardiography on diagnosis, management and patient anxiety. J Clin Epidemiol. 1988;41(2):151–161. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(88)90089-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newburger J. W., Rosenthal A., Williams R. G., Fellows K., Miettinen O. S. Noninvasive tests in the initial evaluation of heart murmurs in children. N Engl J Med. 1983 Jan 13;308(2):61–64. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198301133080201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakley C. M. Controversies in the prophylaxis of infective endocarditis: a cardiological view. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1987 Sep;20 (Suppl A):99–104. doi: 10.1093/jac/20.suppl_a.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilowsky I. Abnormal illness behaviour. Br J Med Psychol. 1969 Dec;42(4):347–351. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1969.tb02089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]