Summary

During DNA double-strand-break (DSB) repair by recombination, the broken chromosome uses a homologous chromosome as a repair template. Early steps of recombination are well characterized: DSB-ends assemble filaments of RecA-family proteins that catalyze homologous pairing and strand-invasion reactions. By contrast, the post-invasion steps of recombination are poorly characterized. Rad52 plays an essential role during early steps of recombination by mediating assembly of RecA-homolog, Rad51, into nucleoprotein filaments. The meiosis-specific RecA-homolog, Dmc1, does not show this dependence, however. By exploiting the Rad52-independence of Dmc1, we reveal that Rad52 promotes post-invasion steps of both crossover and noncrossover pathways of meiotic recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. This activity resides in the N-terminal region of Rad52, which can anneal complementary DNA strands, and is independent of its Rad51-assembly function. Our findings show that Rad52 functions in temporally and biochemically distinct reactions, and suggest a general annealing mechanism for reuniting DSB-ends during recombination.

Introduction

The template-directed repair of chromosomes by homologous recombination plays essential roles in DNA replication, DNA repair and homolog segregation during meiosis (Heyer, 2006; Krogh and Symington, 2004; Hunter, 2006). The in vivo events of meiotic recombination are particularly well characterized. Spo11-catalyzed DNA double-strand-breaks (DSBs) are processed to produce long single-stranded 3’-tails. Resected DSB-ends then assemble filaments of RecA-like proteins, which catalyze homologous pairing and strand-invasion reactions. Most eukaryotes possess two RecA homologs: Rad51, which functions in both mitotic and meiotic cells, and the meiosis-specific Dmc1 (Neale and Keeney, 2006; Shinohara and Shinohara, 2004). Assembly of Rad51 and Dmc1 nucleoprotein filaments requires accessory factors to overcome the inhibitory effect of the single-stranded binding protein, RPA, bound to DSB-ends. The archetypal mediator is Rad52, which catalyzes assembly of Rad51 filaments onto RPA-coated single-stranded DNA (Gasior et al., 2001; Gasior et al., 1998; Krejci et al., 2002; New et al., 1998; Shinohara and Ogawa, 1998; Sugawara et al., 2003; Sung, 1997). During meiosis, assembly of Rad51 into chromatin-associated immunostaining foci shows a strict dependence on Rad52 (Gasior et al., 1998). Dmc1 does not share this dependence, however, and its assembly may be mediated by dedicated factors such as the Mei5-Sae3 complex (Bishop, 1994; Hayase et al., 2004).

Products of strand-invasion can be detected in vivo as Single-End-Invasion (SEI) intermediates, in which one DSB-end has undergone strand-exchange with a homologous chromosome (Hunter and Kleckner, 2001) (Figure 1C). Interaction of the second DSB-end and recombination-associated DNA synthesis leads to formation of the double-Holliday junction (dHJ), which is subsequently resolved into crossover products (Schwacha and Kleckner, 1995) (Figure 1C). The majority of meiotic DSBs are repaired not as crossovers, however, but as noncrossovers without reciprocal exchange of chromosome arms. Noncrossovers are thought to form primarily via synthesis-dependent strand-annealing (SDSA) in which an invading DSB-end is first extended by DNA synthesis, displaced from the template and then annealed to the other DSB-end (Nassif et al., 1994; Paques and Haber, 1999).

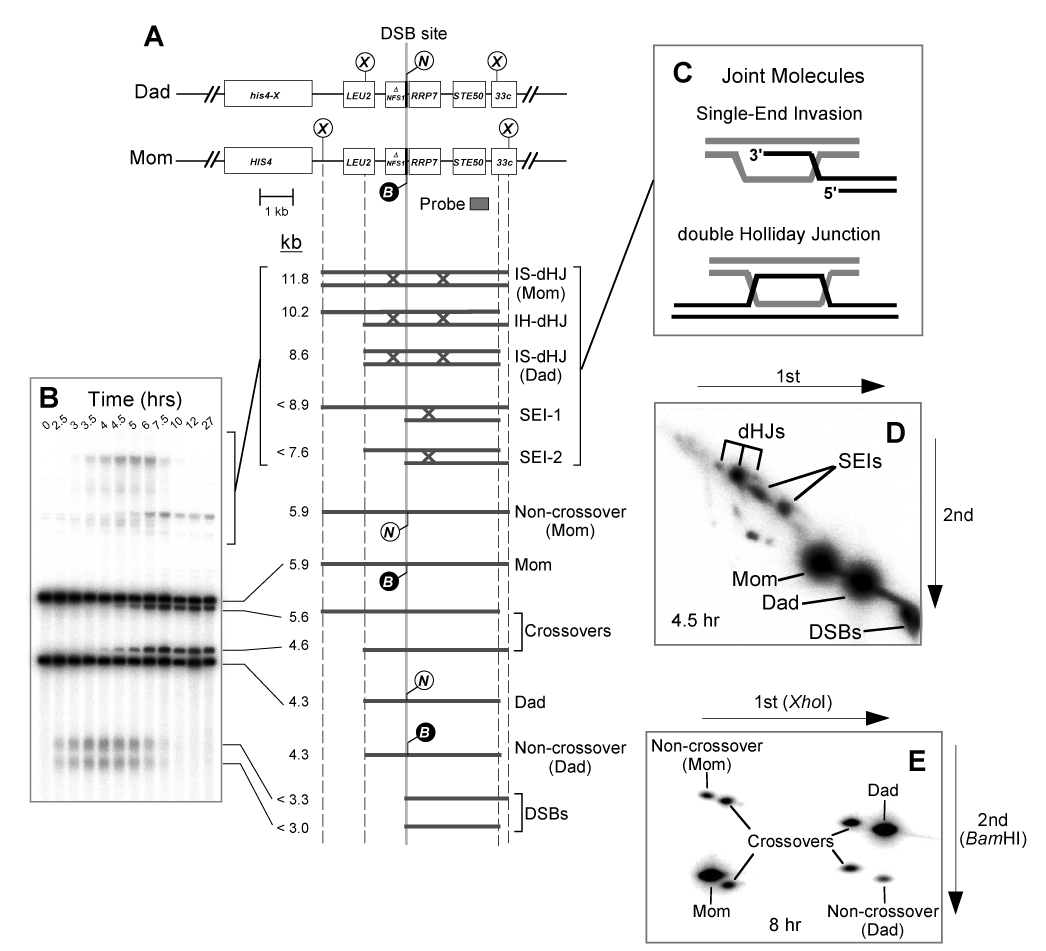

Figure 1. Experimental System.

(A) Map of the HIS4LEU2 locus showing diagnostic restriction sites and position of the probe, Probe 4. DNA species detected following Southern hybridization are shown below. SEI-1 and SEI-2 are the two major SEI species detected with Probe 4 (Hunter and Kleckner, 2001). Lollipops indicate restriction sites: X, XhoI; B, BamHI; N, NgoMIV.

(B) Image of one-dimensional (1D) gel hybridized with Probe 4 showing DNA species detailed in (A).

(C) Predicted structures of SEI and dHJ joint molecule intermediates.

(D) Image of native/native 2D gel hybridized with Probe 4. Species detailed in (A) are highlighted.

(E) 2D gel assay for detecting noncrossovers and crossovers (Martini et al., 2006). XhoI-digested DNA is resolved in the first dimension, digested in the gel with BamHI to determine the status of the central polymorphism, and then resolved again in the second dimension. The eight spots detected by Southern hybridization with Probe 4 correspond to those shown in (A). Four crossover products are observed because crossovers can carry either the BamHI or the NgoMIV allele.

In contrast to the early steps of meiotic recombination, proteins that catalyze post-invasion steps are ill defined. Along the crossover pathway, the SEI-to-dHJ transition requires the second DSB-end to be “captured” by the SEI. Theoretically, this could occur via a second Dmc1/Rad51-catalyzed strand-invasion reaction. Alternatively, the canonical DSB-repair model (Szostak et al., 1983) posits that the second DSB-end anneals to the displaced-loop of the SEI, which is enlarged as DNA polymerase extends the invading DSB-end. In the context of this model, the complementary strand-annealing activity of Rad52 is proposed to catalyze second-end-capture because, in addition to its mediator function, Rad52 uniquely catalyzes the annealing of complementary DNA strands coated with RPA (Mortensen et al., 1996; Shinohara et al., 1998; Sugiyama et al., 1998; Sugiyama et al., 2006; Wu et al., 2006).

Investigating putative post-invasion functions of Rad52 during Rad51-dependent DSB-repair is thwarted by its epistatic function in assembling Rad51 filaments. By exploiting the Rad52-independence of Dmc1, however, we show that Rad52 promotes both the SEI-to-dHJ transition and the completion of noncrossover recombination. This activity of Rad52 resides in the conserved N-terminal region, which possesses strand-annealing activity. These data suggest a model in which crossover and noncrossover pathways share a common late step – Rad52-mediated annealing of DSB-ends – and differ only with respect to the fate of the original invading DSB-end.

Results

Assay System

Cultures of wild-type and rad52Δ null mutant cells were induced to undergo meiosis and intermediate steps of recombination were monitored using the HIS4LEU2 physical assay system (Figure 1) (Hunter and Kleckner, 2001). The HIS4LEU2 locus contains a hotspot for formation of meiosis-specific DSBs and DNA events at this site are monitored using a series of gel electrophoresis and Southern hybridization assays. Cell samples (12–15 per time-course) are first treated with psoralen to produce DNA interstrand crosslinks, which stabilize the joint molecule (JM) intermediates, SEIs and dHJs (Figure 1C). XhoI restriction site polymorphisms between parental “Mom” and “Dad” homologs produce fragments diagnostic for parental and recombinant chromosomes, DSBs and JMs. Each hybridizing signal is quantified using a phosphorimager. DSBs and crossovers are quantified from one-dimensional gels (Figure 1B), whereas SEIs and dHJs are analyzed using native/native two-dimensional (2D) gels, which reveal the branched structure of these intermediates (Figure 1D) (Bell and Byers, 1983; Hunter and Kleckner, 2001).

Significant Levels of Crossover Products Form In rad52Δ Cells

Spore formation in rad52Δ cells is inefficient and only dead spores are formed (Game et al., 1980) (data not shown). Using physical assays, significant levels of crossover products are detected in rad52Δ cells, however (~40% of wild-type levels; Figure 2A and 2B), consistent with the study of Borts et al. (Borts et al., 1986). Moreover, crossover formation in rad52Δ cells shows the same dependence on the pro-crossover factor, Msh5 (Borner et al., 2004; Hollingsworth et al., 1995), as seen in wild-type cells suggesting that the normal differentiated pathway is being utilized (Supplemental Figure S1).

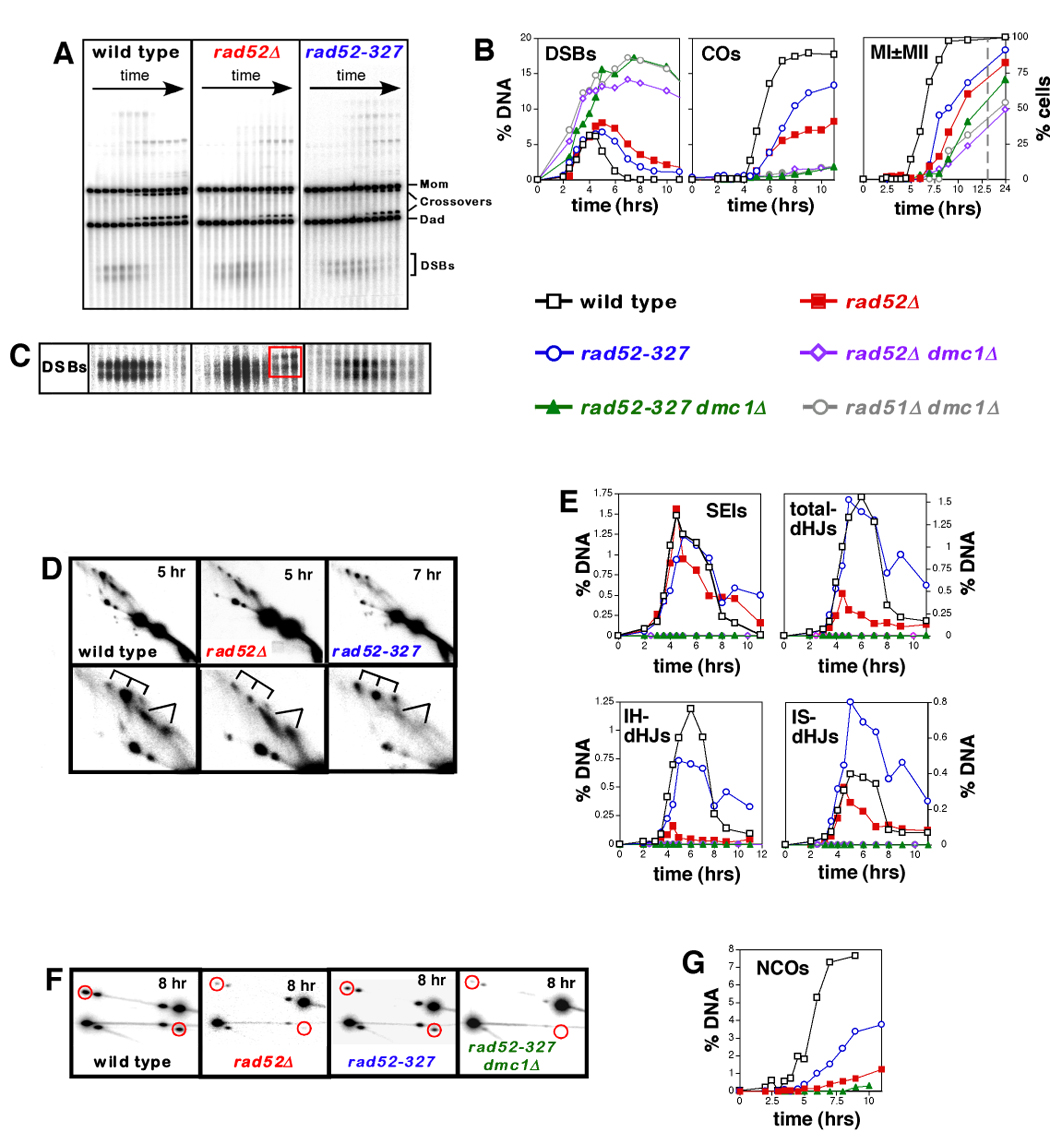

Figure 2. The N-Terminal Region of Rad52 Promotes Post-Invasion Steps of Meiotic Recombination.

(A). Images of 1D gels from wild-type, rad52Δ and rad52-327 time course experiments.

(B) Quantitation of DSBs and crossovers (COs), and analysis of meiotic divisions (MI±MII) in wild type, rad52Δ and rad52-327 strains, and control strains (rad52Δ dmc1Δ, rad52-327 dmc1Δ and rad51Δ dmc1Δ). % DNA is percent of total hybridizing DNA. MI±MII are cells that have completed either the first or second meiotic divisions, as determined by the number of DAPI staining bodies. The dashed grey line marks a break in the X-axis.

(C) Dark exposures of the DSB regions from 1D gels, highlighting the late forming species formed in rad52Δ cells (see Figure S2).

(D) 2D analysis of joint molecules (JMs). In each case, a representative 2D panel is shown together with a blowup of the JM region. SEI and dHJ species are indicated by forked lines and tridents, respectively.

(E) Quantitation of JM formation in wild type, rad52Δ and rad52-327. No JM species were detected in control strains, rad52Δ dmc1Δ, rad52-327 dmc1Δ and rad51Δ dmc1Δ.

(F) Noncrossover analysis for wild-type, rad52Δ, rad52-327 and rad52-327 dmc1Δ time-course experiments (see Figure 1E for details). Each panel shows a representative late time point. Red circles highlight noncrossover signals.

(G) Quantitation of noncrossover formation in wild-type, rad52Δ, rad52-327 and rad52-327 dmc1Δ strains.

Post-Invasion Steps of Recombination Are Defective In rad52Δ Cells

DSBs in rad52Δ cells form with wild-type timing and the majority of breaks appear to turnover, albeit with a delay of ~3 hrs (Figure 2A and 2B); this is mirrored by a similar delay of the first meiotic division (Figure 2B). At late times (>5 hrs), persistent hybridizing species arise that appear to be ~0.3 kb longer than initial DSB molecules (Figure 2C, central panel). Further analysis shows that these molecules are likely to be hairpins resulting from stem-loop formation within the 3’- strand of the DSB-end followed by intra-strand priming of DNA synthesis (see Supplemental Figure S2). We suggest that these aberrant structures form at persistent DSB-ends that failed to be captured in rad52Δ mutant cells (see below). In sharp contrast to rad52Δ cells, rad52Δ dmc1Δ double mutants accumulate high levels of DSBs that persist for the duration of the experiment, indicating a severe block at the DSB stage (Figure 2B). Thus, meiotic recombination in rad52Δ cells progresses beyond the DSB stage in a Dmc1-dependent fashion.

2D gel analysis reveals that rad52Δ cells are defective in the transition from SEIs to dHJs (Figure 2D and 2E). While SEIs reach wild-type levels, peak steady-state levels of interhomolog-dHJs (IH-dHJs) are reduced by 8-fold, from 1.2% of hybridizing DNA in wild type to 0.15% in rad52Δ. By contrast, formation of dHJs between sister-chromatids (IS-dHJs) does not appear to be significantly altered by the rad52Δ mutation. The difference between IH-dHJ and IS-dHJ levels in rad52Δ cells is at least partially explained by the observation that a larger fraction of DSBs is repaired between sister-chromatids in the absence of Rad51 filaments (Schwacha and Kleckner, 1997) (J.P.L and N.H., unpublished). In addition, dependence of dHJ formation on Rad52 may differ between IH and IS pathways. Overall, peak steady-state dHJ levels (IH-dHJs + IS-dHJs) are reduced ~3.5-fold in rad52Δ cells (“total dHJs” in Figure 2E).

The molecular phenotype of the original rad52 allele, rad52-1 (Game et al., 1980) (an A90V amino-acid change) was also examined and found to be qualitatively very similar to the rad52Δ null mutation (Supplemental Figure S3). If anything, rad52-1 exaggerates the defects described in rad52Δ null cells, perhaps because Rad52-1 protein can still localize to recombination sites and block access by other enzymes. Moreover, formation of both IH-dHJs and IS-dHJs is defective in rad52-1 cells.

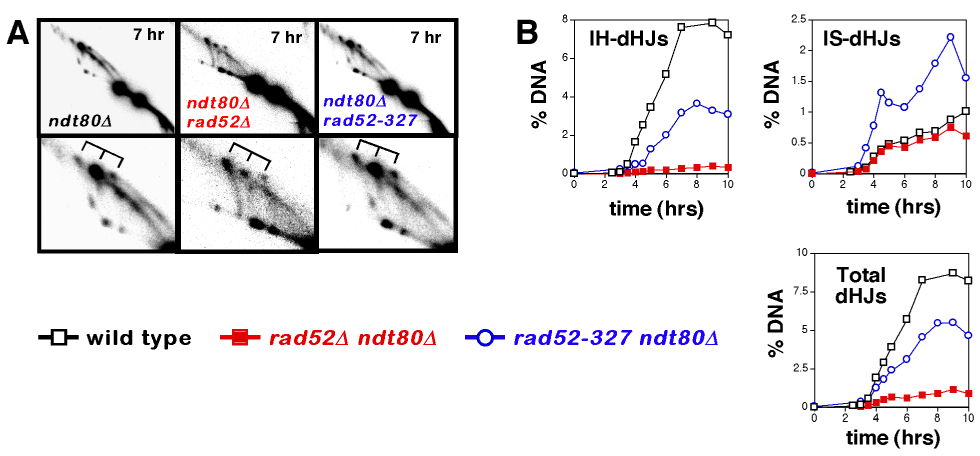

The dramatic reduction of IH-dHJs in rad52Δ cells could, in theory, be explained by a large reduction in the lifespan of IH-dHJs. To address this possibility, we measured dHJ levels in strains carrying an ndt80Δ mutation, which causes dHJs to accumulate (Allers and Lichten, 2001a) (Figure 3). This analysis confirms the inferences made in NDT80 strains. In fact, the effects of the rad52Δ mutation are more exaggerated in the ndt80Δ background. IH-dHJs accumulate to 20-fold lower levels in rad52Δ ndt80Δ cells than in the ndt80Δ single mutant, and total dHJs are reduced by 8-fold. In contrast, IS-dHJ levels are indistinguishable between the two strains. The difference in IH-dHJ levels in NDT80 and ndt80Δ backgrounds could be explained if rad52Δ NDT80 cells do in fact form very few IH-dHJs, but these intermediates have a longer lifespan than normal (relative to both IH-dHJs in wild-type cells and IS-dHJs in rad52Δ cells); as such, the steady-state dHJ level in rad52Δ NDT80 cells will not accurately report the absolute reduction in IH-dHJs. Consequently, the IH-dHJ/IS-dHJ ratio in rad52Δ NDT80 cells will be higher than that in rad52Δ ndt80Δ cells. We conclude that in addition to its well-characterized mediator function, Rad52 is also required for efficient progression from SEIs to dHJs.

Figure 3. Joint Molecule Analysis in the ndt80Δ Background.

(A) Representative images from 2D gel analysis of JMs in ndt80Δ, ndt80Δ rad52Δ and ndt80Δ rad52-327 cells. Lower panels show blowups of the JM regions. dHJ species are indicated by tridents.

(B) Quantitation of JM formation in ndt80Δ, ndt80Δ rad52Δ and ndt80Δ rad52-327 cells.

Strand-Exchange In rad52Δ Mutants Is Dmc1-Dependent

Bishop (Bishop, 1994; Gasior et al., 1998) showed that rad52Δ mutation differentially affects assembly of Rad51 and Dmc1 into immunostaining foci. This result was confirmed by staining spread meiotic chromosomes with antibodies against Rad51 and Dmc1 (Supplemental Figure S4). Dmc1 foci form with essentially normal timing in rad52Δ cells, although the average number of foci per nucleus is reduced ~2-fold. In sharp contrast, assembly of Rad51 foci is completely defective in rad52Δ cells. Consistently, all strand-exchange in rad52Δ cells is Dmc1-dependent: no SEIs or dHJs, and only residual levels of crossovers are detected in rad52Δ dmc1Δ cells. In fact, recombination in rad52Δ dmc1Δ cells is indistinguishable from that in rad51Δ dmc1Δ cells lacking both RecA homologs (Figure 2B and 2E) (Shinohara et al., 1997). Although Dmc1 foci assemble with normal timing in rad52Δ cells, their disassembly is severely delayed, by as much as ~5 hrs (Figure 3B). These persistent Dmc1 foci mirror the delay in DSB turnover and execution of the first meiotic division (above; Figure 2B).

The N-Terminal Region Of Rad52 Promotes Second-End Capture

During the SEI-to-dHJ transition, the second DSB-end could be captured via a second strand-invasion reaction. In this case, defective dHJ formation in rad52Δ cells could be a consequence of failure to assemble Rad51 filaments. Alternatively, second-end-capture may occur via Rad52-mediated annealing of the second DSB-end to the displaced-loop of the SEI (Sugiyama et al., 1998; Szostak et al., 1983). These two possibilities were distinguished in vivo using a separation-of-function allele, rad52-327, which encodes a truncated Rad52 protein lacking the Rad51-interaction domain required for mediator function, but retains the conserved N-terminal region comprising oligomerization, DNA binding and complementary strand-annealing activities (Asleson et al., 1999; Boundy-Mills and Livingston, 1993; Krejci et al., 2002). Consistent with absence of mediator activity, rad52-327 cells fail to assemble Rad51 foci (Supplemental Figure S4). Also, like rad52Δ null mutants, rad52-327 cells assemble immunostaining foci of Dmc1 with normal timing, although again the average number of foci per nucleus is reduced, by ~2.5-fold. rad52-327 cells appear to turnover Dmc1 foci more efficiently than rad52Δ cells, however, with a delay of only ~2 hrs relative to wild type.

Meiotic recombination is also more efficient in rad52-327 cells. Despite the absence of Rad51 foci, dHJ formation is relatively efficient (Figure 2D and 2E). A distinct difference between rad52-327 and wild-type cells is a change in choice of recombination partner. In wild-type cells, IH-dHJs form with a >3-fold preference over IS-dHJs at the HIS4LEU2 locus (Figure 2E) (Hunter and Kleckner, 2001; Schwacha and Kleckner, 1997). Inter-homolog bias makes biological sense during meiosis because intersister recombination does not contribute to chiasma formation. In rad52-327 cells, the ratio of IH-dHJs/IS-dHJs is decreased to one. This phenotype appears to be caused by the absence of Rad51 filaments in rad52-327 cells and is consistent with the loss of interhomolog bias observed in rad51Δ null mutants (Schwacha and Kleckner, 1997) (J.P.L. and N.H. unpublished). Regardless, comparison of total dHJ levels suggests that rad52-327 cells form dHJs at essentially wild-type levels.

dHJ levels were also measured in rad52-327 ndt80Δ cells and the basic patterns observed in NDT80 cells were reiterated (Figure 3). IH-dHJs in rad52-327 ndt80Δ cells accumulate to ~50% of the levels observed in the ndt80Δ single mutant, an increase of 9.5-fold relative to rad52Δ cells. Total dHJ levels accumulate to ~65% of ndt80Δ levels, representing a 5-fold increase over rad52Δ levels. Taken together, these data show that the N-terminal region of Rad52 promotes the transition from SEIs to dHJs.

Crossing-over at HIS4LEU2 in rad52-327 cells reaches ~70% of wild-type levels (Figure 2B). This level of crossing-over is close to that expected given the reduction in inter-homolog bias observed in the rad52-327 strain (~11% crossovers expected versus 13% detected). Moreover, rad52-327 cells sporulate efficiently and produce 29% viable spores (91 of 316 spores analyzed) implying that some or all of the crossovers formed create functional chiasmata that facilitate homolog disjunction.

Rad52 Also Promotes Noncrossover Formation

The specific annealing mechanism we invoke for second-end-capture during dHJ formation is analogous to the annealing step of the SDSA model for noncrossover formation (see Discussion and Figure 4). This similarity prompted us to examine the requirement for Rad52 in noncrossover formation. Noncrossovers at HIS4LEU2 are detected by virtue of a BamHI/NgoMIV polymorphism situated immediately at the DSB site (Figure 1E) (Martini et al., 2006). In wild-type cells, noncrossovers plateau 8 hrs after induction of meiosis, at 7.6% of hybridizing DNA (Figure 2F and 2G). Noncrossovers are strongly Rad52 dependent as shown by the 7-fold reduction observed in rad52Δ cells. In contrast, noncrossovers reach ~50% of wild-type levels in rad52-327 cells, a >3-fold increase over rad52Δ levels. Failure to form noncrossovers at wild-type levels can be explained by the loss of interhomolog bias in rad52-327 cells, described above. Assuming that the reduction in interhomolog bias detected for dHJs reflects a general reduction in interhomolog recombination, we expect ~5% noncrossovers to form in rad52-327 cells; almost 4% noncrossovers are detected in this strain. We conclude that Rad52-catalyzed strand-annealing is also an important step in noncrossover formation.

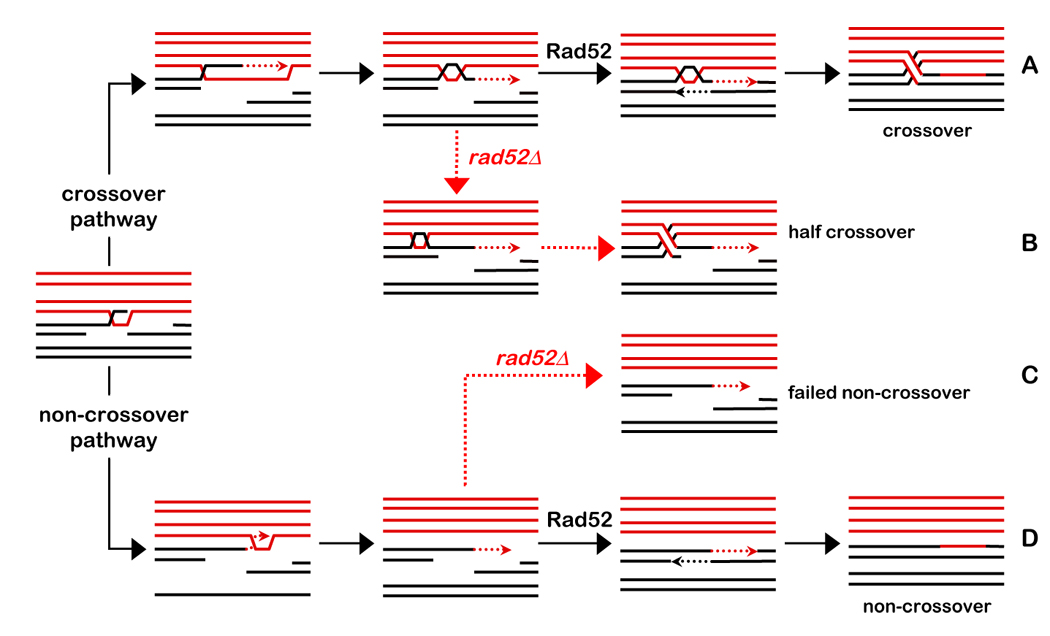

Figure 4. Model for Post-Invasion Steps of Meiotic DSB-repair.

Homologs are shown in red and black, respectively; dashed lines indicate nascent DNA. Solid black arrows indicate pathways in wild-type cells. Dashed red arrows indicate pathways in the rad52Δ mutant. Assignment of a crossover or noncrossover fate follows homolog pairing and Dmc1 catalyzed strand-invasion by one DSB-end to form a nascent D-loop (Borner et al., 2004; Hunter and Kleckner, 2001). The contribution of Rad51 strand-exchange activity at this stage is uncertain.

(A) Along the crossover pathway, the nascent JM is converted into an SEI. Following extension by DNA synthesis, the nascent strand is displaced “end first” and then undergoes Rad52-catalyzed annealing to the second DSB-end. A second round of DNA synthesis and ligation then forms a canonical dHJ.

(B) In rad52Δ cells, second-end-capture fails, but a cryptic dHJ is formed and subsequently resolved into a half-crossover and a broken chromatid.

(C and D) Along the non-crossover pathway, the initial D-loop is extended by DNA synthesis but ultimately disassembles via “end-last” displacement. The two ends then undergo Rad52-catalyzed annealing to seal the break. In rad52Δ cells, annealing fails leaving a broken chromatid.

Discussion

Model of Post-Synaptic Steps of Meiotic Recombination

We present in vivo evidence that post-invasion steps of meiotic recombination in S. cerevisiae are catalyzed by the strand-annealing activity of Rad52. Human RAD52 has recently been shown to mediate single-strand annealing in an in vitro replication-dependent D-loop expansion reaction that recapitulates the second-end-capture mechanism proposed by Szostak et al. (Szostak et al., 1983) (M. McIlwraith and S.C. West, personal communication). Additional features of our in vivo data support a different mode of second-end-capture, however. Both SEIs and dHJs appear to be crossover-specific precursors (Allers and Lichten, 2001a; Borner et al., 2004), but paradoxically, while IH-dHJs are reduced at least 8-fold in rad52Δ cells, crossovers form at ~40% of wild-type levels (18% in wild-type versus 8% in rad52Δ; Figure 2B). To reconcile this observation, we propose that SEIs formed in rad52Δ cells may be resolved to produce nonreciprocal half-crossovers (Figure 4B). This idea derives from the observation of Haber and Hearn (Haber and Hearn, 1985), that very rare crossovers formed in vegetative rad52Δ cells are always non-reciprocal. Specifically, we suggest that the SEI-to-dHJ transition often involves migration of the SEI D-loop away from the DSB-site and “end-first” displacement of the extended DSB-end (Figure 4A), as previously proposed by Allers and Lichten to explain the occurrence of DSB-distal JMs that lack intervening heteroduplex DNA (Allers and Lichten, 2001b). In wild-type cells, the displaced 3’-strand of an SEI would subsequently undergo Rad52-catalyzed annealing to the second DSB-end. In rad52Δ cells, in which second-end capture fails, we propose that the D-loop continues to migrate into the double-stranded region of the DSB-end, converting the SEI into a dHJ lacking a chromosome arm. These cryptic-dHJs could be resolved via a canonical resolution mechanism to form a half-crossover plus a broken chromatid (Figure 4B). Regular formation of cryptic dHJs may be peculiar to the rad52Δ mutant because this predicts the appearance of symmetric heteroduplex associated with crossover products, for which there is little evidence in S. cerevisiae (e.g. Nicolas and Petes, 1994). Thus, in wild-type cells, we predict that second-end capture occurs before a cryptic dHJs can form (Hunter, 2006). It remains possible, however, that significant levels of symmetric heteroduplex are not detected in S. cerevisiae because the inter-HJ distance in dHJs is only ~260 bp (Cromie et al., 2006). We note that there is good evidence for symmetric heteroduplex in other fungi (e.g. Nicolas and Petes, 1994).

It is also possible that Rad52-independent crossovers form via the non-dHJ mechanism proposed to explain crossing-over mediated by Mus81-Eme1, a structure-selective endonuclease in S. pombe (Mus81-Mms4 in S. cerevisiae) (Osman et al., 2003). An argument against this possibility is that Rad52-independent crossovers are strongly dependent on MutS homolog Msh5, which defines a Mus81-Mms4-independent pathway of crossing-over in S. cerevisiae (Supplemental Figure S1) (Argueso et al., 2004; De Los Santos et al., 2003). We note, however, that the non-dHJ mechanism also includes a second-end annealing step that could be catalyzed by Rad52.

During noncrossover formation, the two DSB-ends would also be reunited via Rad52-catalyzed annealing, and crossover and noncrossover pathways would differ only with respect to the fate of the original invading strand. Along the crossover pathway, the invading strand undergoes end-first displacement to preserve the joint molecule; whereas during SDSA, the invading strand is displaced “end last” to dissociate the joint molecule (Figure 4A and 4D).

Unregulated crossing-over can cause chromosome rearrangements, missegregation and homozygosis of deleterious mutations (Richardson et al., 2004). To minimize these risks, somatic cells actively suppress crossing-over (Ira et al., 2003; Johnson and Jasin, 2001). In contrast, meiotic crossover control mechanisms must act to ensure that each homolog pair obtains at least one crossover (Jones, 1984). Thus, regulating the formation of crossover-specific dHJs is a critical aspect of DSB-repair in all cell types. A potential target of such regulation is Rad52-mediated second-end-capture. In particular, it may be important to regulate the strand-annealing activity of Rad52 in order to prevent spontaneous dHJ formation and aberrant crossing-over.

Experimental Procedures

Yeast Strains and Genetic Techniques

Strains are described in Supplemental Table 1. The HIS4LEU2 locus has been described (Hunter and Kleckner, 2001; Martini et al., 2006).

Time Course Experiments

Meiotic time courses and DNA physical assays were performed as described (Borner et al., 2004; Goyon and Lichten, 1993; Hunter and Kleckner, 2001; Martini et al., 2006; Schwacha and Kleckner, 1995).

Cytology

Immunostaining was performed as described (Hayase et al., 2004; Shinohara et al., 2000).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dennis Livingston (University of Minnesota) for plasmids carrying the rad52-1 and rad52-327 alleles, Michael McIlwraith and Steve West for communicating unpublished data and Eric Kofoid and John Roth for assisting in identification of stem-loop motifs. This work was supported by NIH NIGMS grant GM074223 to N.H.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Allers T, Lichten M. Differential timing and control of noncrossover and crossover recombination during meiosis. Cell. 2001a;106:47–57. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00416-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allers T, Lichten M. Intermediates of yeast meiotic recombination contain heteroduplex DNA. Mol Cell. 2001b;8:225–231. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00280-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argueso JL, Wanat J, Gemici Z, Alani E. Competing crossover pathways act during meiosis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2004;168:1805–1816. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.032912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asleson EN, Okagaki RJ, Livingston DM. A core activity associated with the N terminus of the yeast RAD52 protein is revealed by RAD51 overexpression suppression of C-terminal rad52 truncation alleles. Genetics. 1999;153:681–692. doi: 10.1093/genetics/153.2.681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell L, Byers B. Separation of branched from linear DNA by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis. Analyt Biochem. 1983;130:527–535. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(83)90628-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop DK. RecA homologs Dmc1 and Rad51 interact to form multiple nuclear complexes prior to meiotic chromosome synapsis. Cell. 1994;79:1081–1092. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borner GV, Kleckner N, Hunter N. Crossover/noncrossover differentiation, synaptonemal complex formation, and regulatory surveillance at the leptotene/zygotene transition of meiosis. Cell. 2004;117:29–45. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00292-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borts RH, Lichten M, Haber JE. Analysis of meiosis-defective mutations in yeast by physical monitoring of recombination. Genetics. 1986;113:551–567. doi: 10.1093/genetics/113.3.551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boundy-Mills KL, Livingston DM. A Saccharomyces cerevisiae RAD52 allele expressing a C-terminal truncation protein: activities and intragenic complementation of missense mutations. Genetics. 1993;133:39–49. doi: 10.1093/genetics/133.1.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cromie GA, Hyppa RW, Taylor AF, Zakharyevich K, Hunter N, Smith GR. Single Holliday junctions are intermediates of meiotic recombination. Cell. 2006;127:1167–1178. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Los Santos T, Hunter N, Lee C, Larkin B, Loidl J, Hollingsworth NM. The Mus81/Mms4 endonuclease acts independently of double-holliday junction resolution to promote a distinct subset of crossovers during meiosis in budding yeast. Genetics. 2003;164:81–94. doi: 10.1093/genetics/164.1.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Game JC, Zamb TJ, Braun RJ, Resnick M, Roth RM. The role of radiation (rad) genes in meiotic recombination in yeast. Genetics. 1980;94:51–68. doi: 10.1093/genetics/94.1.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasior SL, Olivares H, Ear U, Hari DM, Weichselbaum R, Bishop DK. Assembly of RecA-like recombinases: distinct roles for mediator proteins in mitosis and meiosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:8411–8418. doi: 10.1073/pnas.121046198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasior SL, Wong AK, Kora Y, Shinohara A, Bishop DK. Rad52 associates with RPA and functions with Rad55 and Rad57 to assemble meiotic recombination complexes. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2208–2221. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.14.2208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyon C, Lichten M. Timing of molecular events in meiosis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: stable heteroduplex DNA is formed late in meiotic prophase. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:373–382. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.1.373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haber JE, Hearn M. Rad52-independent mitotic gene conversion in Saccharomyces cerevisiae frequently results in chromosomal loss. Genetics. 1985;111:7–22. doi: 10.1093/genetics/111.1.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayase A, Takagi M, Miyazaki T, Oshiumi H, Shinohara M, Shinohara A. A protein complex containing Mei5 and Sae3 promotes the assembly of the meiosis-specific RecA homolog Dmc1. Cell. 2004;119:927–940. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyer WD. Biochemisty of eukaryotic homologous recombination. In: Aguilera A, Rothstein R, editors. Homologous Recombination. Springer-Verlag: Heidelberg; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hollingsworth NM, Ponte L, Halsey C. MSH5, a novel MutS homolog, facilitates meiotic reciprocal recombination between homologs in Saccharomyces cerevisiae but not mismatch repair. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1728–1739. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.14.1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter N. Meiotic Recombination. In: Aguilera A, Rothstein R, editors. Molecular Genetics of Recombination. Springer-Verlag: Heidelberg; 2006. pp. 381–442. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter N, Kleckner N. The single-end invasion: an asymmetric intermediate at the double-strand break to double-holliday junction transition of meiotic recombination. Cell. 2001;106:59–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00430-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ira G, Malkova A, Liberi G, Foiani M, Haber JE. Srs2 and Sgs1-Top3 suppress crossovers during double-strand break repair in yeast. Cell. 2003;115:401–411. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00886-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RD, Jasin M. Double-strand-break-induced homologous recombination in mammalian cells. Biochem Soc Trans. 2001;29:196–201. doi: 10.1042/0300-5127:0290196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones GH. The control of chiasma distribution. Symp Soc Exp Biol. 1984;38:293–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krejci L, Song B, Bussen W, Rothstein R, Mortensen UH, Sung P. Interaction with Rad51 is indispensable for recombination mediator function of Rad52. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:40132–40141. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206511200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogh BO, Symington LS. Recombination proteins in yeast. Annu Rev Genet. 2004;38:233–271. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.38.072902.091500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martini E, Diaz RL, Hunter N, Keeney S. Crossover homeostasis in yeast meiosis. Cell. 2006;126:285–295. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortensen UH, Bendixen C, Sunjevaric I, Rothstein R. DNA strand annealing is promoted by the yeast Rad52 protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:10729–10734. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.10729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nassif N, Penney J, Pal S, Engels WR, Gloor GB. Efficient copying of nonhomologous sequences from ectopic sites via P-element-induced gap repair. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:1613–1625. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.3.1613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neale MJ, Keeney S. Clarifying the mechanics of DNA strand exchange in meiotic recombination. Nature. 2006;442:153–158. doi: 10.1038/nature04885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- New JH, Sugiyama T, Zaitseva E, Kowalczykowski SC. Rad52 protein stimulates DNA strand exchange by Rad51 and replication protein A. Nature. 1998;391:407–410. doi: 10.1038/34950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolas A, Petes TD. Polarity of meiotic gene conversion in fungi: contrasting views. Experientia. 1994;50:242–252. doi: 10.1007/BF01924007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osman F, Dixon J, Doe CL, Whitby MC. Generating crossovers by resolution of nicked Holliday junctions: a role for Mus81-Eme1 in meiosis. Mol Cell. 2003;12:761–774. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00343-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paques F, Haber JE. Multiple pathways of recombination induced by double-strand breaks in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1999;63:349–404. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.63.2.349-404.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson C, Stark JM, Ommundsen M, Jasin M. Rad51 overexpression promotes alternative double-strand break repair pathways and genome instability. Oncogene. 2004;23:546–553. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwacha A, Kleckner N. Identification of double Holliday junctions as intermediates in meiotic recombination. Cell. 1995;83:783–791. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90191-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwacha A, Kleckner N. Interhomolog bias during meiotic recombination: meiotic functions promote a highly differentiated interhomolog-only pathway. Cell. 1997;90:1123–1135. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80378-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinohara A, Gasior S, Ogawa T, Kleckner N, Bishop DK. Saccharomyces cerevisiae recA homologues RAD51 and DMC1 have both distinct and overlapping roles in meiotic recombination. Genes Cells. 1997;2:615–629. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1997.1480347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinohara A, Ogawa T. Stimulation by Rad52 of yeast Rad51-mediated recombination. Nature. 1998;391:404–407. doi: 10.1038/34943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinohara A, Shinohara M. Roles of RecA homologues Rad51 and Dmc1 during meiotic recombination. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2004;107:201–207. doi: 10.1159/000080598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinohara A, Shinohara M, Ohta T, Matsuda S, Ogawa T. Rad52 forms ring structures and co-operates with RPA in single-strand DNA annealing. Genes Cells. 1998;3:145–156. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1998.00176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinohara M, Gasior SL, Bishop DK, Shinohara A. Tid1/Rdh54 promotes colocalization of Rad51 and Dmc1 during meiotic recombination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:10814–10819. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.20.10814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugawara N, Wang X, Haber JE. In vivo roles of Rad52, Rad54, and Rad55 proteins in Rad51-mediated recombination. Mol Cell. 2003;12:209–219. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00269-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama T, Kantake N, Wu Y, Kowalczykowski SC. Rad52-mediated DNA annealing after Rad51-mediated DNA strand exchange promotes second ssDNA capture. Embo J. 2006;25:5539–5548. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama T, New JH, Kowalczykowski SC. DNA annealing by RAD52 protein is stimulated by specific interaction with the complex of replication protein A and single-stranded DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:6049–6054. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung P. Function of yeast Rad52 protein as a mediator between replication protein A and the Rad51 recombinase. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:28194–28197. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.45.28194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szostak JW, Orr-Weaver TL, Rothstein RJ, Stahl FW. The double-strandbreak repair model for recombination. Cell. 1983;33:25–35. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90331-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Sugiyama T, Kowalczykowski SC. DNA annealing mediated by Rad52 and Rad59 proteins. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:15441–15449. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601827200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.