Abstract

Cognitive Behavioral Social Skills Training (CBSST) is a 24-session weekly group therapy intervention to improve functioning in people with schizophrenia. In our prior randomized clinical trial comparing treatment as usual (TAU) with TAU plus group CBSST (Granholm et al. 2005), participants with schizophrenia in CBSST showed significantly better functional outcome than participants in TAU. The present study was a secondary analysis of neuropsychological predictors of functional outcome in our prior CBSST trial. We examined (1) whether neuropsychological impairment at baseline moderated functional outcome in CBSST relative to TAU, and (2) whether improvement in neuropsychological abilities mediated improvement in functional outcome in CBSST. Attention, verbal learning/memory, speed of processing, and executive functions were assessed at baseline, end of treatment, and 12-month follow-up. Greater severity of neuropsychological impairment at baseline predicted poorer functional outcome for both treatment groups (nonspecific predictor), but the interaction between severity of neuropsychological impairment and treatment group was not significant (no moderation). Effect sizes for the difference between treatment groups on functional outcome measures at 12-month follow-up were similar for participants with relatively mild (d=.44–.64) and severe (d=.29–.60) neuropsychological impairment. Results also did not support the hypothesis that improvement in neuropsychological abilities mediated improvement in functioning in CBSST. Adding CBSST to standard pharmacologic care, therefore, improved functioning relative to standard care alone, even for participants with severe neuropsychological impairment, and this improvement in functioning was not related to improvement in neuropsychological abilities in CBSST.

Keywords: Schizophrenia, cognitive behavior therapy, social skills training, neuropsychological impairment, functioning

There is considerable evidence that neuropsychological impairment is associated with poor functioning in people with schizophrenia (Bowen et al. 1994;Green et al. 2000;Kern et al. 1992;Lysaker et al. 1995;McKee et al. 1997;Penn et al. 1995). Neuropsychological impairment is also a strong predictor of poor outcome in psychosocial interventions that target functional impairments in this population. In social skills training (SST), for example, deficits in verbal memory, executive functioning, and sustained attention have been associated with poor attendance and poor skills acquisition (McKee et al. 1997;Mueser et al. 1991;Kern et al. 1992;Smith et al. 1999;Ucok et al. 2006;Silverstein et al. 1998). In supported employment and vocational rehabilitation interventions, learning and memory, processing speed and abstraction/flexibility have been associated with poor work performance (McGurk and Mueser 2004;Lysaker et al. 2005).

Cognitive-behavior therapy (CBT) interventions have also targeted functioning in people with schizophrenia. While most CBT for psychosis studies have focused on reducing severity of treatment-resistant psychotic symptoms (For review see: Gould et al. 2001;Dickerson 2000;Rector and Beck 2001;Turkington et al. 2006), some studies have found significant improvements in functioning in CBT (Wiersma et al. 2001;Bradshaw 2000;Roberts et al. 2004;Gumley et al. 2003;Granholm et al. 2005). It is reasonable to assume that neuropsychological impairment might be a barrier to success in CBT, given that CBT interventions seem to rely heavily on cognitive abilities, like learning, memory, hypothesis testing, and attention to evidence. There is little empirical evidence, however, to support this assumption. Few studies have examined the relationship between neuropsychological impairment and outcome in CBT for any psychiatric disorder. One study of CBT for psychosis (Leclerc et al. 2000) found that attention and learning and memory did not moderate outcome in CBT relative to standard care. Another study of CBT for psychosis (Garety et al. 1997), found that only one of four neuropsychological tests was a significant moderator of symptom outcome, but the finding was counter-intuitive: More severe neuropsychological impairment was associated with better symptom outcome.

We developed a group therapy intervention for functional impairment in schizophrenia that combined CBT and SST called, Cognitive Behavioral Social Skills Training (CBSST) (Granholm et al. 2004;McQuaid et al. 2000). By adding CBT to SST, thoughts that interfere with skill performance in the real world (e.g., low self-efficacy, expectancy and ability beliefs) can be addressed in therapy. CBSST was specifically designed to help middle-aged and older people with schizophrenia attain personalized functioning goals. Only a few other studies have examined psychotherapy interventions for the growing population of older people with schizophrenia (Bartels et al. 2004;Pratt et al. 2006;Patterson et al. 2006). In a randomized controlled trial comparing treatment as usual (TAU) with TAU plus group CBSST (Granholm et al. 2005), we previously found significantly greater skill acquisition and functioning in CBSST relative to TAU at the end of treatment, and these benefits were maintained at 12-month posttreatment follow-up (Granholm et al. 2007).

The present study was a secondary analysis of associations between neuropsychological functioning and functional outcome in our previous CBSST trial. Attention/vigilance, verbal learning/memory, speed of processing, and executive functions were assessed at baseline, end of treatment and 12-month follow-up in our prior CBSST trial, but results for these measures have not been previously reported. Although the association between neuropsychological impairment and outcome in CBT remains unclear, neuropsychological impairment has been found to be a significant predictor of poor outcome in SST for schizophrenia (McKee et al. 1997;Mueser et al. 1991;Kern et al. 1992;Smith et al. 1999;Ucok et al. 2006;Silverstein et al. 1998). Greater severity of neuropsychological impairment assessed at baseline, therefore, was hypothesized to be associated with poorer functional outcome at 12-month post-treatment follow-up in CBSST. In addition, CBSST trains skills in hypothesis testing, evidence gathering, problem-solving, and reasoning, which are frontal/executive abilities associated with functioning in people with schizophrenia (Green et al. 2000). It was, therefore, hypothesized that neuropsychological abilities (especially frontal/executive abilities) would improve significantly more in CBSST relative to TAU, and that this improvement in neuropsychological abilities would be associated with improvement in functional outcome in CBSST (mediation).

METHODS

Sample

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of California, San Diego, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants or their legal guardians. Participants with either schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (N = 65) based on the Structured Clinical Interview for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (First M.B. et al. 1995) were recruited from outpatient treatment centers and residential settings in San Diego, California. Exclusion criteria for the study were disabling medical problems that would interfere with treatment, absence of medical records to inform diagnosis, or a comorbid substance dependence diagnosis (other than caffeine or nicotine) within the past six months. The average age of the sample at baseline was 53.3 (SD=7.1). The majority of the participants were Caucasian (78%), male (74%), single (92%), non-veterans (63%), with a high school education (years of education M=12.4; SD=2.4), living in assisted housing (62%). At baseline, the mean total Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) (Kay et al. 1987) score for the sample was 52.3 (SD=13.3). Sixteen participants were prescribed at least one second generation antipsychotic medication, 39 at least one typical antipsychotic, 6 both typical and second generation antipsychotics, and 4 were not prescribed any antipsychotic medications. Thirty-four participants were also prescribed antidepressant medications, and 19 mood-stabilizers. Daily dosages of antipsychotic and anticholinergic medications were calculated as chlorpromazine equivalents (mg/day CPZE at baseline: CBSST M= 446.7, SD= 386.2; TAU M= 532.7, SD = 588.6) and clinically recommended benztropine equivalents (mg/day BZTE at baseline: CBSST M= 1.4, SD= 2.1; TAU M= 1.8, SD = 2.4) (Foster 1989;Jeste and Wyatt 1982;Saddock and Saddock 2000).

Procedure

Participants were randomly assigned to TAU (n=32) or CBSST (n=33) and assessed at baseline, end of treatment and 12 months post-treatment. Assessors were independent of the treatment and blind to treatment group assignment. In treatment as usual (TAU), participants continued in whatever ongoing care they were receiving. No medication or other treatment guidelines were provided. In CBSST, participants received 24 weekly 2-hour group psychotherapy sessions. SST components were modified from symptom management, communication role-play, and problem-solving SST modules available from Psychiatric Rehabilitation Consultants (Psychiatric Rehabilitation Consults 1991). The CBT components were developed specifically for patients with schizophrenia (Beck and Rector 2000;Kingdon and Turkington 1994). Cognitive interventions targeted beliefs about psychotic symptoms, dysfunctional performance beliefs and negative self-efficacy beliefs that interfered with functioning behaviors. Age-relevant content modifications included identifying and challenging ageist beliefs (e.g., “I’m too old to learn”), age-relevant role-play situations (e.g., talking to a doctor about eyeglasses), and age-specific problem solving (e.g., finding transportation, coping with hearing and vision problems). Additional details of study methodology, participant characteristics, and specifics of the interventions can be found elsewhere (Granholm et al. 2002;Granholm et al. 2004;Granholm et al. 2005;McQuaid et al. 2000).

Functional Outcome Measures

Knowledge and application of skills trained in the intervention were assessed using a modified version of the Comprehensive Module Test (CMT) (Psychiatric Rehabilitation Consults 1991). Questions about coping and skills trained with vignettes requiring skill application were used to assess mastery of CBSST skills, including communication, problem-solving and thought challenging. The Independent Living Skills Survey (ILSS) (Wallace et al. 2000) was used to assess functioning. A composite score of five ILSS domains (appearance & clothing, personal hygiene, health maintenance, transportation, leisure and community) assessed self-reported basic and social functioning activities performed in the past month. The ILSS has been found to be reliable and sensitive to differences between healthy controls and older people with schizophrenia (Perivoliotis et al. 2004), and was sensitive to treatment effects in our prior CBSST trial (Granholm et al. 2005;2007).

Treatment Adherence

Attendance at each of the 24 sessions was recorded. In addition, following each therapy session, the two CBSST group therapists rated each participant’s participation in group discussions on a 5-point Likert scale (1, “none,” to 5, “very active”), and these ratings were averaged for all sessions attended. The percentage of homework assignments attempted (homework was assigned in every session), regardless of quality of completion, was also recorded for all sessions attended.

Neuropsychological Domains

Participants completed a comprehensive battery of tests that indexed neuropsychological domains relevant to functioning (Green 1996;Green et al. 2000), including speed of processing, executive functioning, attention and vigilance, and verbal learning and memory. The neuropsychological measures (and references to normative data used to convert raw scores to demographically-corrected T-scores) were as follows: For speed of processing, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale - III Digit Symbol subtest (Wechsler 1997), Stroop Color and Word subtests (Golden 1978), and TrailMaking Test – A (Reitan and Wolfson 1993;Heaton et al. 1991) for executive, TrailMaking Test – B (Reitan and Wolfson 1993;Heaton et al. 1991), Stroop Interference score (Golden 1978), Controlled Oral Word Association Task – FAS total (Gladsjo et al. 1999), and Wisconsin Card Sorting Test – Perseveration errors (Heaton et al. 1993); for verbal learning and memory, California Verbal Learning Test - Trials 1–5 total, recognition discrimination, and long delay free recall (Delis et al. 2000) (Norman et al. 2000), and for attention and vigilance, Span of Apprehension (SOA) Task, 10-letter array percent correct (Asarnow et al. 1991), Degraded Stimulus Continuous Performance Test (DS-CPT)– total d’ (Nuechterlein 1991), Digit Span Distractibility Task (DSDT) – distraction condition percent correct (Oltmanns and Neale 1975). The mean T-score within each domain was computed and a global impairment T-score was computed as the average of all available T-scores. Participants with available T-scores for at least two neuropsychological tests in a domain were included in the sample for that domain, at that particular time point, and global T-scores were calculated for participants with available data for at least ten of the neuropsychological tests. Data for the visual information processing tasks (SOA, DS-CPT) were discarded for participants without normal/corrected vision of 20/40 or better, so sample size was smaller for the attention and vigilance domain relative to other domains (see Table 1 and Table 2). The mean global neuropsychological impairment T-score at baseline for participants with (M = 34.55; SD = 6.75; n = 52) and without (M = 36.33; SD = 5.53; n = 10) normal/corrected vision did not differ significantly, t(60) = 0.80, p = .427.

Table 1.

Results of Linear Regression Modeling: Neuropsychological Functioning at Baseline as a Predictor of 12-Month Post-Treatment Functioning (ILSS) and Skill Knowledge (CMT)

| Functioning (ILSS) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline T-Score | Group x Baseline | |||||||

| Domain | β | Std β | t | p | B | Std β | t | p |

| Global1 | 0.005 | 0.313 | 2.469 | 0.017 | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.011 | 0.991 |

| Executive Control1 | 0.003 | 0.215 | 1.637 | 0.107 | −0.0001 | −0.005 | 0.035 | 0.972 |

| Attention & Vigilance2 | 0.004 | 0.329 | 2.109 | 0.042 | 0.001 | 0.033 | 0.216 | 0.830 |

| Verbal Learning & Memory3 | 0.002 | 0.229 | 1.771 | 0.082 | <0.001 | 0.022 | 0.168 | 0.867 |

| Speed of Processing4 | 0.006 | 0.307 | 2.365 | 0.022 | 0.001 | 0.021 | 0.163 | 0.871 |

| Skill Knowledge (CMT) | ||||||||

| Baseline T-Score | Group x Baseline | |||||||

| Domain | β | Std β | t | p | β | Std β | t | p |

| Global5 | 0.552 | 0.439 | 3.828 | <0.001 | −0.122 | −0.049 | 0.423 | 0.674 |

| Executive Control5 | 0.388 | 0.339 | 2.801 | 0.007 | −0.221 | −0.096 | 0.798 | 0.428 |

| Attention & Vigilance2 | 0.323 | 0.381 | 2.577 | 0.014 | 0.027 | 0.016 | 0.109 | 0.914 |

| Verbal Learning & Memory6 | 0.350 | 0.471 | 4.173 | <0.001 | −0.002 | −0.001 | 0.010 | 0.992 |

| Speed of Processing1 | 0.231 | 0.170 | 1.294 | 0.201 | −0.053 | −0.019 | 0.148 | 0.883 |

Notes: ILSS = Independent Living Skills Survey composite; CMT = Comprehensive Baseline = Domain T-score at baseline; Group = CBSST or TAU

df = 54

df = 36

df = 56

df = 53

df=55

df=57.

Table 2.

Results of Multilevel Modeling: Change in Neurocognitive Functioning Over Time and Treatment

| N | N | Parameter | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome Measure | CBSST | TAU | Variables | Estimate | t | p |

| Global | 31 | 32 | Intercept | 37.805 | ||

| Group | −0.910 | −0.526 | 0.601 | |||

| Time | 0.153 | 3.198 | 0.002 | |||

| Group by Time | −0.043 | −0.626 | 0.534 | |||

| Executive Control | 31 | 32 | Intercept | 38.313 | ||

| Group | −2.220 | −1.043 | 0.301 | |||

| Time | 0.185 | 3.011 | 0.004 | |||

| Group by Time | −0.159 | −1.824 | 0.073 | |||

| Attention and | 24 | 23 | Intercept | 35.872 | ||

| Vigilance | Group | 4.555 | 1.598 | 0.117 | ||

| Time | 0.163 | 1.388 | 0.172 | |||

| Group by Time | 0.035 | 0.209 | 0.835 | |||

| Verbal Learning | 32 | 32 | Intercept | 38.979 | ||

| and Memory | Group | −3.108 | −1.057 | 0.295 | ||

| Time | 0.163 | 1.656 | 0.103 | |||

| Group by Time | −0.073 | −0.527 | 0.600 | |||

| Speed of | 30 | 30 | Intercept | 37.312 | ||

| Processing | Group | −1.496 | −0.884 | 0.380 | ||

| Time | 0.129 | 2.673 | 0.010 | |||

| Group by Time | −0.045 | −0.643 | 0.523 | |||

Normative data were not available for the measures included in the attention and vigilance domain. T-scores for the measures in this domain, therefore, were calculated based on data collected from 94 healthy controls divided into four groups based on age (40–49; 50–59; 60–69; and 70–79 years of age). Healthy controls were excluded for neurological disorders (e.g., seizures) or head injury with loss of consciousness (>30 min.), substance dependence disorder (DSM-IV criteria) other than nicotine or caffeine in the past 6 months, uncorrected or corrected visual acuity worse than 20/40 (based on a Snellen wall chart eye exam); ocular damage or disease, eye surgery or ocular medications; or insulin-dependent diabetes. Healthy controls were 77% Caucasian and 54% female, with an average of 13.8 (SD=1.8) years of education. Across age groups, the range of means and standard deviations used to compute age-corrected T-scores for attention and vigilance measures were as follows: DS-CPT - d’ score, M=1.13–1.74, SD=0.54–0.70, SOA – 10-letter array % correct, M=73.44–79.08, SD=7.62–9.49, and DSDT-distraction condition % correct, M=70.34–77.50, SD=15.83–23.05.

Statistical Analyses

The original sample included 76 participants (Granholm et al. 2005), but 11 participants were excluded from analyses in the present study due to missing neuropsychological test data at baseline or missing functional outcome data at 12-month follow-up, leaving a final sample of 65 participants (86% retention rate). Baseline global neuropsychological impairment T-scores were available for 6 of the 11 excluded participants, and included (M = 34.81; SD = 6.56) and excluded participants (M = 32.15; SD = 12.39) did not differ significantly, t(66) = 0.88, p = .381.

The procedures outlined by Kraemer et al. (2002) were followed in testing for moderation and mediation. Linear regression models were used to examine whether baseline neuropsychological impairment moderated functional outcome on the ILSS composite and skill acquisition on the CMT Total. Group (coded as CBSST=0.5; TAU=−0.5), baseline neuropsychological domain T-score, and the interaction between group and baseline domain T-score were included in these moderation models. The domain baseline scores were centered about their means. A second set of linear regression models examined whether change in neuropsychological functioning (domain T-score difference between 12-month follow-up and baseline) mediated outcome at 12-month follow-up on the same functional outcome measures. Group (coded as CBSST = 0.5; TAU = −0.5), domain change score, and the interaction between group and the domain change score were included in this set of mediation models.

Multilevel modeling (MLM) techniques (Singer and Willett 2003) were used to examine whether neuropsychological abilities improved in the treatment groups. A separate growth curve model predicting each level-1 outcome variable (global; executive control; attention and vigilance; verbal learning and memory; speed of processing) was estimated using time (in months) as a level-1 predictor and group (CBSST, TAU) as a level-2 predictor of both the slope and intercept parameters. Because the focus of this study was on the 12-month follow-up, time was centered about this assessment, so the group variable provided a test of group differences at 12-month follow-up. Participants with at least two of the three assessments (baseline, end of treatment, 12-month follow-up) on a given outcome measure were included in these models.

RESULTS

Neuropsychological Predictors of Outcome

Results from the linear regression moderation models are presented in Table 1. The main effect of baseline neuropsychological impairment on functional outcome (ILSS) was significant for the global, attention and vigilance, and speed of processing domain scores, indicating that more severe neuropsychological impairment was associated with poorer functional outcome for the total sample. The main effect of baseline neuropsychological impairment on skill knowledge (CMT) was significant for the global, executive control, attention and vigilance, and verbal learning and memory domain scores, which indicated that more severe neuropsychological impairment was associated with poorer skill knowledge for the total sample.

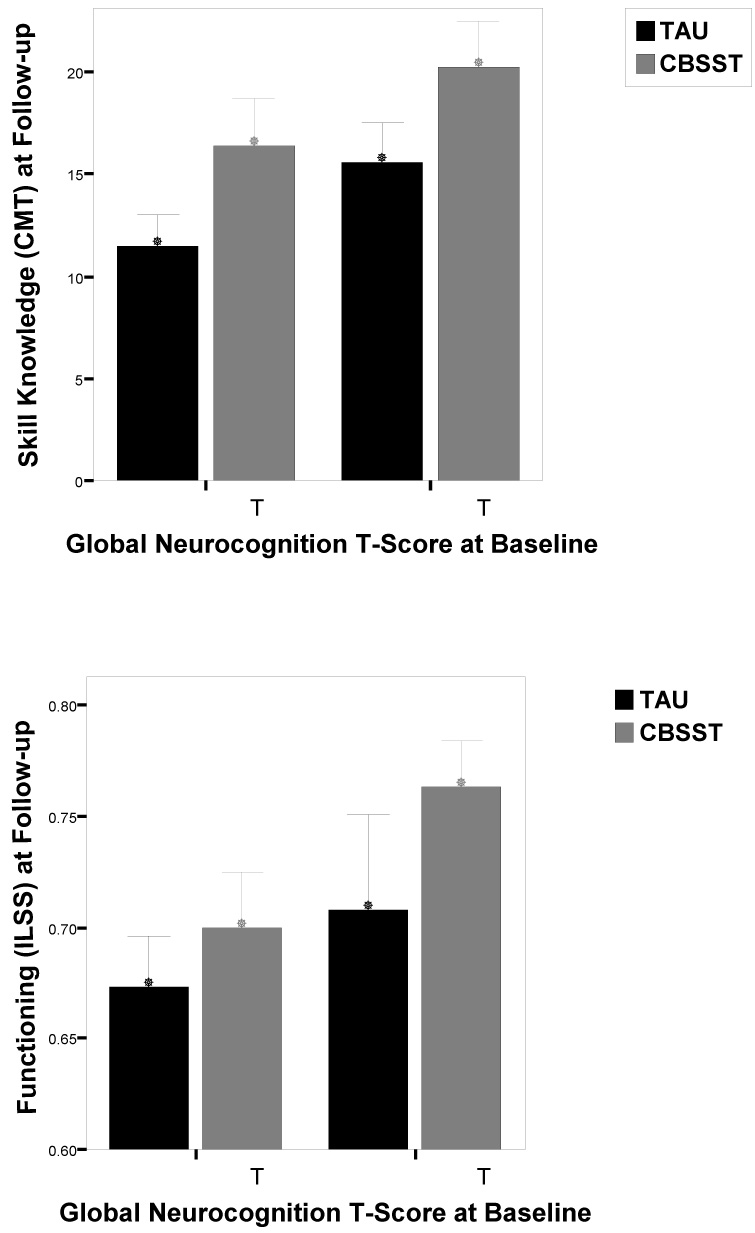

However, the group X baseline neuropsychological impairment interaction was not significant for any domain for either outcome measure (IlSS or CMT; Table 1), which indicated that the effect of neuropsychological impairment on outcome did not differ significantly between CBSST and TAU groups. Although participants with poorer neuropsychological abilities generally had poorer outcomes in both treatments, participants with mild and severe neuropsychological deficits showed comparable benefit in CBSST+TAU, relative to TAU, alone. To illustrate this finding, the sample was split at the median global neuropsychological T-score at baseline (T=34), and mean ILSS and CMT scores at 12-month follow-up are shown in Figure 1 for participants with mild (T>34) and severe (T<34) neuropsychological impairment in each treatment group. Effect sizes for the difference between treatment groups on functional outcome measures at 12-month follow-up were similar for participants with relatively mild (CMT: d=.64; ILSS: d=.44) and severe (CMT: d=.60; ILSS: d=.29) impairment.

Figure 1.

The sample was split at the median global neuropsychological (NP) impairment T-score at baseline (T=34), and mean Comprehensive Module Test (CMT; top) and Independent Living Skills Survey (ILSS; bottom) scores at 12-month follow-up are shown for participants with mild (T>34) and severe (T<34) NP impairment in Cognitive Behavioral Social Skills Training (CBSST) and Treatment as Usual (TAU) conditions. Sample sizes for CMT: low NP/TAU (n=16); low NP/CBSST (n=15); high NP/TAU (n=14); high NP/CBSST (n=14); for ILSS: low NP/TAU (n=16); low NP/CBSST (n=14); high NP/TAU (n=14); high NP/CBSST (n=14).

Neuropsychological Predictors of Treatment Adherence

For participants in CBSST (n=30), baseline global neurocognitive T-score was significantly positively correlated with the percentage of homework assignments completed (r=.48, p=.007) and mean ratings of participation in group discussions (r=.66, p<.001), but not with number of sessions attended (r=−.11, p=.548). Participants with more severe neuropsychological impairment, therefore, completed fewer homework assignments and were less active participants in group.

Neuropsychological Outcomes and Mediation

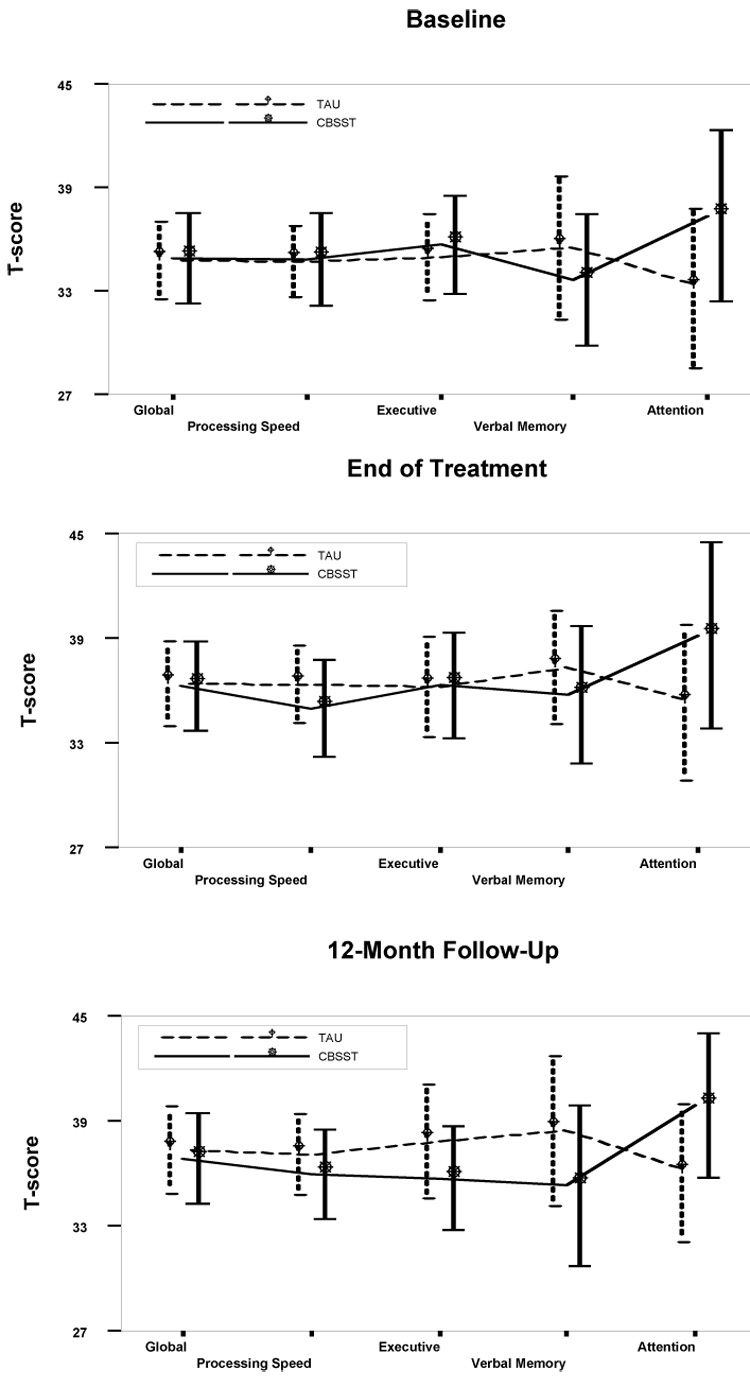

Figure 2 shows the mean and 95% confidence interval for each neuropsychological domain, by time point. The groups did not differ significantly in any domain at any time point. Results from the multilevel modeling analysis are presented in Table 2. The effect of time was significant for the global, executive control, and speed of processing domains, indicating that participants improved in these domains over time, irrespective of group membership. No significant group main effect or group by time interaction was found for any domain. Treatment groups, therefore, did not differ significantly at the 12-month follow-up and growth rates between CBSST and TAU were similar across domains. Contrary to predictions, these results indicated that improvement in neuropsychological abilities did not mediate improvement in functioning or skill acquisition in CBSST (Kraemer et al. 2002). In addition, the linear regression mediation models showed that the main effect of change in neuropsychological ability and the group X change in neuropsychological ability interaction were not significant for any domain score.

Figure 2.

Mean T-score and 95% confidence interval (error bars) for each neurocognitive domain at each assessment time point for participants in Cognitive Behavioral Social Skills Training (CBSST; N=31) and Treatment as Usual (TAU; N=32) conditions. The treatment groups did not differ significantly in any domain at any time point.

Comorbid Neurologic Illness

Participants were not excluded for comorbid neurologic illness or traumatic brain injury, so the potential impact of such neurologic insults on neuropsychological functioning was examined. A dichotomous variable indicating neurologic illness was created (= 1 if participant reported ever having loss of consciousness > 30 min or a seizure or other neurologic illness; = 0 otherwise), and this variable, as well as the interactions between this variable and time and group, were added to the MLM for global T-score as the outcome. The effect of this neurologic illness variable was significant (parameter estimate = −6.454, p=0.042), indicating that participants with a neurologic insult had lower global T-scores at 12-month follow up, relative to participants without neurologic insult. The effect of time remained significant (parameter estimate = 0.154, p=0.003), suggesting that global T-scores increased over time, regardless of treatment group membership or neurologic condition. No other variable or interaction effect was significant. Therefore, although participants with comorbid neurologic illness had significantly greater neuropsychological impairment than participants without neurologic illness, their treatment trajectories did not differ significantly.

Medications and Symptoms

To examine and adjust for relationships between medications, symptoms, global neuropsychological impairment T-scores, and outcome (ILSS and CMT), the linear regression models described above were re-estimated with medication and symptom variables added. For medications, CPZE, BZTE, CPZE X group interaction, and BZTE X group interaction predictors were added. For symptoms, PANSS Negative Subscale total, PANSS Positive Subscale total, and Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression total (Hamilton 1967), along with the interaction with group for each of these symptom variables were added. None of the predictors in the medication model for ILSS were significant. Although the main effect of global baseline T-score was reduced to a trend, the effect size was similar to the original model in Table 1 (std β=0.276, p=0.061). In the medication model for CMT, the global T-score predictor remained significant with larger effect size relative to the original model in Table 1 (std β=0.537, p<0.001), but none of the other predictors were significant. The symptom model for ILSS also produced a significant effect with comparable effect size for the global T-score predictor (std β=0.349, p=0.018), but none of the other predictors were significant. In the symptom model for CMT, the baseline PANSS Positive Subscale total emerged as a significant predictor (std β= −0.278, p=0.038), but the global T-score was still a significant predictor with comparable effect size to the original model in Table 1 (std β=0.463, p<0.001). In sum, greater severity of global neuropsychological impairment continued to be a meaningful predictor of poorer outcome at 12-month follow-up, even when medications and symptom severity were adjusted for as covariates in the regression models.

DISCUSSION

This study examined neuropsychological predictors of functional outcome in a randomized clinical trial of CBSST for middle-aged and older people with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. We previously reported that participants in CBSST showed greater skills acquisition and superior self-reported functioning relative to participants in TAU at end of treatment (Granholm et al. 2005) and these gains were maintained at 1-year follow-up (Granholm et al. 2007). The present study found that neuropsychological impairment was a nonspecific predictor of skills acquisition and functional outcome in CBSST. Greater severity of neuropsychological impairment predicted poorer skills acquisition and functional outcome at 12- month follow-up for both treatment groups. Neuropsychological impairment, however, was not found to be a significant moderator of outcome in CBSST. The necessary group X neuropsychological impairment interactions in the statistical models used to test for moderation were not significant (Kraemer et al. 2002).

It is important to stress that the null effects found in this study cannot “prove” that neuropsychological impairment did not moderate outcome in CBSST relative to TAU. Effect sizes for the treatment group effect, however, were similar for participants with relatively mild (d=.44–.64) and severe (d=.29–.60) neurocognitive impairment, and effect sizes for the group X neuropsychological impairment interactions were close to zero or even in the opposite direction (std β = −.001 to +.033). Participants in CBSST, therefore, showed comparable benefit relative to TAU, regardless of severity of neuropsychological impairment. Given that neuropsychological impairment is more common in older people with psychosis (Jeste et al. 1999), it is particularly important that adding CBSST to standard pharmacologic care improved functioning relative to standard care alone, even for older participants with severe neuropsychological impairment.

Referring clinicians may not recommend CBT or other psychosocial interventions for people with psychotic disorders, because neuropsychological impairment is common in these individuals and it is often assumed that this might be a barrier to success in psychotherapy. This may not be an accurate assumption. Studies of SST for schizophrenia, for example, found that greater severity of neuropsychological impairment was associated with poorer outcome (McKee et al. 1997;Mueser et al. 1991;Kern et al. 1992;Smith et al. 1999;Ucok et al. 2006;Silverstein et al. 1998), but these studies did not examine whether neuropsychological impairment differentially impacted outcome relative to a control group, which is required for moderation (Kraemer et al. 2002). Neuropsychological impairment predicted poorer outcome in general in these studies (nonspecific predictor), but it cannot be concluded that participants with greater neuropsychological impairment would not benefit from adding SST to standard care, relative to standard care, alone. The present study, as well as one other study of CBT for psychosis (Leclerc et al. 2000), found that neuropsychological impairment did not significantly moderate outcome in CBT relative to standard care. Further, more severe neuropsychological impairment was associated with better symptom outcome in another study of CBT for psychosis (Garety et al. 1997). Published research, therefore, has provided no support for the assumption that people with neuropsychological impairment should be excluded from CBT for psychosis.

Consistent with previous research (McKee et al. 1997;Kern et al. 1992), participants with more severe neuropsychological impairment were less active participants in group and completed fewer homework assignments. Unlike prior research, neuropsychological impairment was not significantly correlated with attendance in sessions in this CBSST trial, but this may have been due to restricted range in this sample with excellent attendance (M= 22 [92%] of 24 sessions; 95% C.I.= 21–23). Transportation to therapy groups was also provided in this CBSST trial, which may have compensated for the negative impact of neuropsychological impairment on attendance. Nonetheless, even when present in group, participants with more severe neuropsychological impairment participated less and attempted fewer homework assignments. We (Granholm et al. 2006) previously found that greater CBSST group participation was associated greater improvement in total symptoms, and greater homework adherence was associated with greater skill acquisition. Improving group participation and homework adherence in participants with more severe neuropsychological impairment, therefore, may improve treatment outcomes.

Results of this study did not support the hypothesis that improvement in neuropsychological functioning mediates improvement in skills acquisition and independent living skills in CBSST. Neuropsychological test performance improved to a similar extent in CBSST and TAU and improvement in neuropsychological functioning was not significantly associated with improvement in skills acquisition or independent living skills. Other cognitive mechanisms, like changing dysfunctional performance beliefs (e.g., “Why bother, I will fail” or “It’s too hard; not worth the effort”) through cognitive therapy, may have contributed to improvement in functional outcome. Changing these cognitions may not require changing underlying basic neurocognitive abilities.

Some researchers (Brenner et al. 1992;Perris and Skagerlind 1994) have described two broad categories of cognitive interventions for schizophrenia: Cognitive remediation, which focuses on rehabilitation of specific cognitive functions (e.g., memory, attention), and CBT, which trains participants to use metacognitive strategies to identify and challenge unhelpful or inaccurate thoughts. Perris and Skagerlind (Perris and Skagerlind 1994) point out that these areas of intervention have several factors in common and may lie on a continuum from more ‘molecular’ to more ‘molar’ cognitive rehabilitation approaches. At one end, cognitive remediation targets specific problems of neurocognitive processing, and at the other end, CBT targets more global cognitive constructs, such as thinking about thinking (metacognition) experiences and self-concept. Both approaches often involve repeated practice of skills, behavioral rewards for attention to task, self-instruction and inductive reasoning strategies applied to thinking and social perception, and hypothesis testing and problem-solving training to promote cognitive flexibility. CBSST incorporates all of these cognitive remediation factors, but the present study did not find significantly greater improvement in any neuropsychological domain in CBSST relative to improvements found for standard care. It is possible that the specific tests selected were not sufficiently sensitive to the types of neurocognitive improvements expected in CBT (e.g., reasoning, flexibility, problem-solving). It is also possible that incorporating repeated practice of specific neurocognitive skills might lead to greater improvement in neurocognition in CBSST, which may, in turn, improve clients’ ability to apply the reasoning, thought challenging and problem solving skills trained in CBSST.

Strengths of the study included a well-controlled clinical trial design, appropriate mediation/moderation analyses (Kraemer et al. 2002), an understudied population, good retention of participants, and a relatively thorough evaluation of neuropsychological abilities associated with functional outcome in schizophrenia. Limitations included null findings in the context of a moderately small sample size, but comparable treatment effect sizes were found for subsamples with mild and severe neuropsychological impairment and effect sizes for interaction effects were very small or even in the opposite direction of moderation. In addition, exclusion of people with current comorbid substance dependence may reduce the generalization of the findings, but comorbid substance dependence declines with age in people with schizophrenia (Palmer et al. 1999) and might interfere with neuropsychological testing. Participants also were not excluded for comorbid neurologic illness, which may interfere with neurocognitive rehabilitation, but accounting for neurologic illness in analyses did not alter the pattern of results. Finally, medications and symptoms also might impact neuropsychological test scores and functional outcomes, but adjusting for these variables in analyses also did not alter the pattern of results.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Office of Research and Development, Medical Research Service, Department of Veterans Affairs, and the National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH61381 and 1P30MH066248). The authors thank Helena Kraemer, Ph.D., for statistical consultation. Portions of this research were presented at the 2006 Society for Research in Psychopathology Meeting, San Diego, CA, and the 2007 International Congress for Research on Schizophrenia, Colorado Springs, CO.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- Asarnow RF, Granholm E, Sherman T. Span of apprehension in schizophrenia. In: Steinhauer SR, Gruzelier JH, Zubin J, editors. Handbook of Schizophrenia: Neurophsychology, Psychophysiology, and Information Processing. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1991. pp. 335–370. [Google Scholar]

- Bartels SJ, Forester B, Mueser KT, Miles KM, Dums AR, Pratt SI, Sengupta A, Littlefield C, O'Hurley S, White P, Perkins L. Enhanced skills training and health care management for older persons with severe mental illness. Community Ment Health J. 2004;J. 40:75–90. doi: 10.1023/b:comh.0000015219.29172.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Rector NA. Cognitive therapy of schizophrenia: A new therapy for the new millennium. Am J Psychother. 2000;54:291–300. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.2000.54.3.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen L, Wallace CJ, Glynn SM, Nuechterlein KH, Lutzker J, Kuehnel TG. Schizophrenic individual's cognitive functioning and performance in interpersonal interactions and skills training procedures. J Psychiatr Res. 1994;28:289–301. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(94)90012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw W. Integrating cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy for persons with schizophrenia into a psychiatric rehabilitation program: Results of a three year trial. Community Ment Health J. 2000;36:491–500. doi: 10.1023/a:1001911730268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner HD, Hodel B, Roder V, Corrigan P. Treatment of cognitive dysfunctions and behavioral deficits in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1992;18:21–26. doi: 10.1093/schbul/18.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delis DS, Kaplan E, Kramer JH, Ober BA. California Verbal Learning Test-II (CVLT-II) Manual. San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson FB. Cognitive behavioral psychotherapy for schizophrenia: A review of recent empirical studies. Schizophr Res. 2000;43:71–90. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(99)00153-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders-Patient Edition (SCID-I/P) New York Psychiatric Institute; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Foster P. Neuroleptic equivalence. Pharmacology. 1989;290:431–432. [Google Scholar]

- Garety P, Fowler D, Kuipers E, Freeman D, Dunn G, Bebbington P, Hadley C, Jones S. London-East Anglia randomised controlled trial of cognitive-behavioural therapy for psychosis. II: Predictors of outcome. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;171:420–426. doi: 10.1192/bjp.171.5.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladsjo JA, Schuman CC, Evans JD, Peavy GM, Miller SW, Heaton RK. Norms for letter and category fluency: demographic corrections for age, education, and ethnicity. Assessment. 1999;6:147–178. doi: 10.1177/107319119900600204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden CJ. Stroop Color and Word Test. Chicago: Stoelting Company; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Gould RA, Mueser KT, Bolton E, Mays V, Goff D. Cognitive therapy for psychosis in schizophrenia: An effect size analysis. Schizophr Res. 2001;48:335–342. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(00)00145-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granholm E, Auslander L, Gottlieb JD, McQuaid JR, McClure FS. Therapeutic factors contributing to change in cognitive-behavioral group therapy for older persons with schizophrenia. J Contemp Psychother. 2006;36:31–41. [Google Scholar]

- Granholm E, McQuaid JR, Auslander L, McClure FS. Group cognitive-behavioral social skills training for older outpatients with chronic schizophrenia. J Cognit Psychother. 2004;18:265–279. [Google Scholar]

- Granholm E, McQuaid JR, McClure FS, Auslander L, Perivoliotis D, Pedrelli P, Patterson T, Jeste DV. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioral social skills training for middle-aged and older outpatients with chronic schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:520–529. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.3.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granholm E, McQuaid JR, McClure FS, Link PC, Perivoliotis D, Gottlieb JD, Patterson TL, Jeste DV. Randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioral social skills training for older people with schizophrenia: 12-month follow-up. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:730–737. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n0510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granholm E, McQuaid JR, McClure FS, Pedrelli P, Jeste DV. A randomized controlled pilot study of cognitive behavioral social skills training for older patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2002;53:167–169. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(00)00186-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MF. What are the functional consequences of neurocognitive deficits in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:321–330. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MF, Kern RS, Braff DL, Mintz J. Neurocognitive deficits and functional outcome in schizophrenia: are we measuring the "right stuff"? Schizophr Bull. 2000;26:119–136. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gumley A, O'Grady M, McNay L, Reilly J, Power K, Norrie J. Early intervention for relapse in schizophrenia: Results of a 12-month randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioural therapy. Psychol Med. 2003;33:419–431. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703007323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. Br J Soc Clin Psychol. 1967;6:278–296. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1967.tb00530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton RK, Chelune GJ, Talley JL, Kay GG, Curtiss G. Wisconsin Card Sorting Test Manual- Revised and Expanded. Odeassa, Fla: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Heaton RK, Grant I, Matthews CG. Comprehensive norms for Expanded Halstead-Reitan Battery: Demographic corrections, research findings, and clinical applications. Odessa, Fla: Psychological Assessment Resources Inc; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Jeste DV, Rockwell E, Harris MJ, Lohr JB, Lacro J. Conventional vs. newer antipsychotics in elderly patients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1999;7:70–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeste D, Wyatt R. Understanding and Treating Tardive Dyskinesia. New York: Guilford; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13:261–276. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern RS, Green MF, Satz P. Neuropsychological predictors of skills training for chronic psychiatric patients. Psychiatry Res. 1992;43:223–230. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(92)90055-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingdon DG, Turkington D. Cognitive-behavioral therapy of schizophrenia. New York: The Guilford Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer HC, Wilson GT, Fairburn CG, Agras WS. Mediators and moderators of treatment effects in randomized clinical trials. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:877–883. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.10.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leclerc C, Lesage AD, Ricard N, Lecomte T, Cyr M. Assessment of a new rehabilitative coping skills module for persons with schizophrenia. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2000;70:380–388. doi: 10.1037/h0087644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lysaker PH, Bell MD, Bioty SM. Cognitive deficits in schizophrenia. Prediction of symptom change for participators in work rehabilitation. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1995;183:332–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lysaker PH, Bryson GJ, Davis LW, Bell MD. Relationship of impaired processing speed and flexibility of abstract thought to improvements in work performance over time in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2005;75:211–218. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGurk SR, Mueser KT. Cognitive functioning, symptoms, and work in supported employment: a review and heuristic model. Schizophr Res. 2004;70:147–173. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee M, Hull JW, Smith TE. Cognitive and symptom correlates of participation in social skills training groups. Schizophr Res. 1997;23:223–229. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(96)00090-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQuaid JR, Granholm E, McClure FS, Roepke S, Pedrelli P, Pedrelli TL, Jeste DV. Development of an integrated cognitive-behavioral and social skills training intervention for older patients with schizophrenia. J Psychother Pract Res. 2000;9:149–156. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueser KT, Bellack AS, Douglas MS, Wade JH. Prediction of social skill acquisition in schizophrenic and major affective disorder patients from memory and symptomatology. Psychiatry Res. 1991;37:281–296. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(91)90064-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman MA, Evans JD, Miller SW, Heaton RK. Demographically corrected norms for the California Verbal Learning Test. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2000:80–94. doi: 10.1076/1380-3395(200002)22:1;1-8;FT080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuechterlein KH. Vigilance in schizophrenia and related disorders. In: Steinhauer SR, Grzonka A, Zubin J, editors. Handbook of Schizophrenia. Vol. 5. Elsevier Science Inc; 1991. pp. 377–433. [Google Scholar]

- Oltmanns TF, Neale JM. Schizophrenic performance when distractors are present: attentional deficit or differential task difficulty? J Abnorm Psychol. 1975;84:205–209. doi: 10.1037/h0076721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer BW, Heaton SC, Jeste DV. Older patients with schizophrenia: Challenges in the coming decades. Psychiatr Serv. 1999;50:1178–1183. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.9.1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson TL, McKibbin CL, Mausbach BT, Goldman S, Bucardo J, Jeste DV. Functionial Adaptation Skills Training (FAST): A randomized trial of a psychosocial intervention for middle-aged and older patients with chronic psychotic disorders. Schizophr Res. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penn DL, Mueser KT, Spaulding W, Hope DA, Reed D. Information processing and social competence in chronic schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1995;21:269–281. doi: 10.1093/schbul/21.2.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perivoliotis D, Granholm E, Patterson TL. Psychosocial functioning on the Independent Living Skills Survey in older outpatients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2004;69:307–316. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2003.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perris C, Skagerlind L. Cognitive therapy with schizophrenic patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1994;382:65–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1994.tb05868.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt SI, Mueser KT, Driscoll M, Wolfe R, Bartels SJ. Medication nonadherence in older people with serious mental illness: Prevalence and correlates. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2006;29:299–310. doi: 10.2975/29.2006.299.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psychiatric Rehabilitation Consults. Modules in the UCLA Social and Independent Living Skills Series. Camarillo, Ca.: Psychiatric Rehabilitation Consults; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Rector NA, Beck AT. Cognitive behavioral therapy for schizophrenia: An empirical review. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2001;189:278–287. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200105000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitan RM, Wolfson D. The Halstead-Reitan Neuropsychological Test Battery: Theory and Clinical Interpretation. 2. Tucson, Ariz.: Neuropsychology Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts DL, Penn DL, Cather C, Otto M, Goff DC. Should CBT target the social impairments associated with schizophrenia? J Cognit Psychother. 2004;18:621–630. [Google Scholar]

- Saddock V, Saddock B. Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. Lippincott: Williams & Wilkins; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein SM, Schenkel LS, Valone C, Nuernberger SW. Cognitive deficits and psychiatric rehabilitation outcomes in schizophrenia. Psychiatr Q. 1998;69:169–191. doi: 10.1023/a:1022197109569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied Longitudinal Data Analysis: Methods for Studying Change and Event Occurence. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Smith TE, Hull JW, Romanelli S, Fertuck E, Weiss KA. Symptoms and neurocognition as rate limiters in skills training for psychotic patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:1817–1818. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.11.1817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turkington D, Kingdon D, Weiden PJ. Cognitive behavior therapy for schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:365–373. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.3.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ucok A, Cakir S, Duman ZC, Discigil A, Kandemir P, Atli H. Cognitive predictors of skill acquisition on social problem solving in patients with schizophrenia. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006;256:388–394. doi: 10.1007/s00406-006-0651-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace CJ, Liberman RP, Tauber R, Wallace J. The Independent Living Skills Survey: A comprehensive measure of the community functioning of severely and persistently mentally ill individuals. Schizophr Bull. 2000;26:631–658. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale. Third Edition. San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Wiersma D, Jenner JA, van de Willige G, Spakman M, Nienhuis FJ. Cognitive behaviour therapy with coping training for persistent auditory hallucinations in schizophrenia: A naturalistic follow-up study of the durability of effects. Acta Psychiatrica Sandinavica. 2001;103:393–399. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2001.00213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]