Abstract

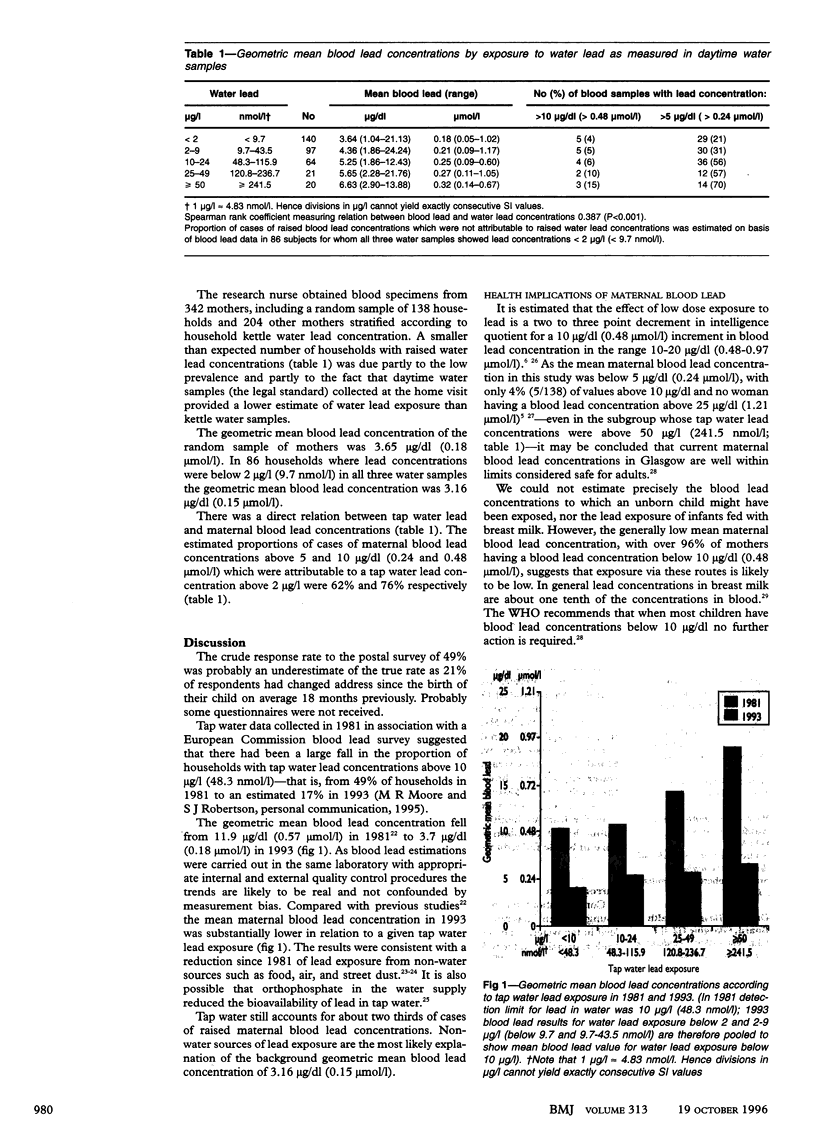

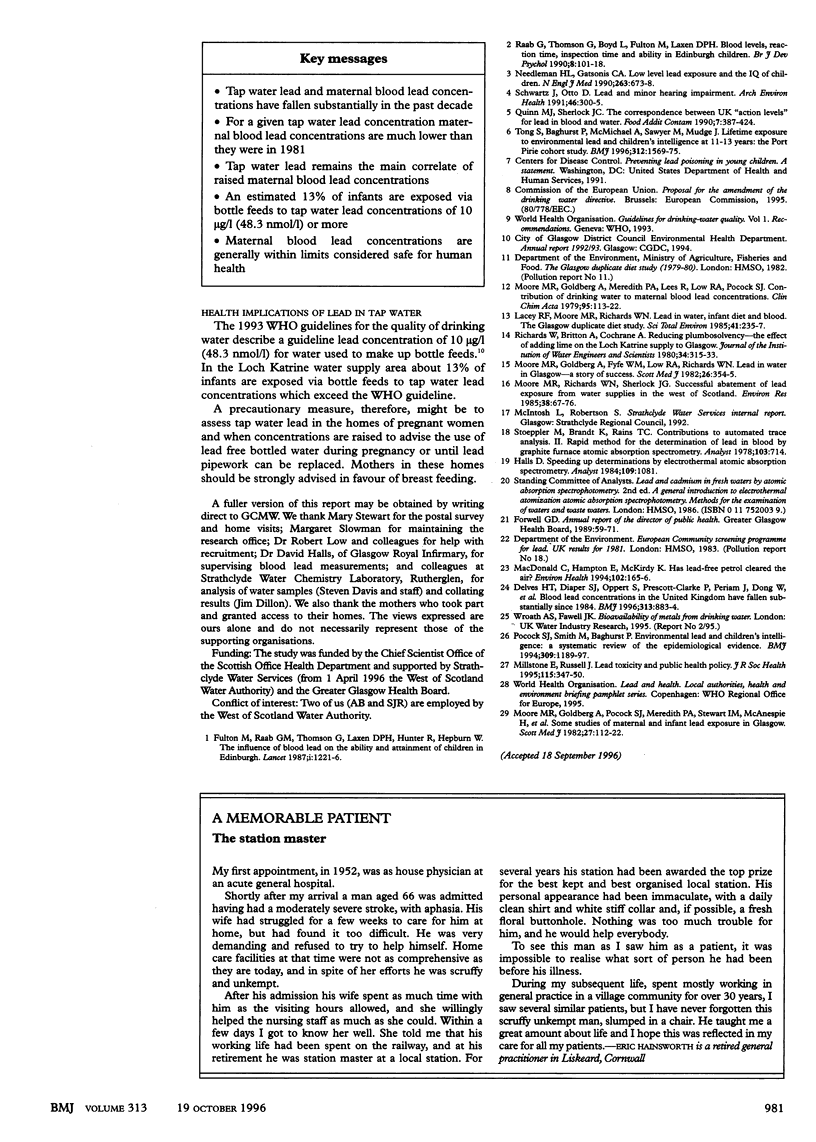

OBJECTIVE: To assess the relation between tap water lead and maternal blood lead concentrations and assess the exposure of infants to lead in tap water in a water supply area subjected to maximal water treatment to reduce plumbosolvency. DESIGN: Postal questionnaire survey and collection of kettle water from a representative sample of mothers; blood and further water samples were collected in a random sample of households and households with raised water lead concentrations. SETTING: Loch Katrine water supply area, Glasgow. SUBJECTS: 1812 mothers with a live infant born between October 1991 and September 1992. Blood lead concentrations were measured in 342 mothers. MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES: Mean geometric blood lead concentrations and the prevalence of raised tap water lead concentration. RESULTS: 17% of households had water lead concentration of 10 micrograms/l (48.3 nmol/l) or more in 1993 compared with 49% of households in 1981. Tap water lead remained the main correlate or raised maternal blood lead concentrations and accounted for 62% and 76% of cases of maternal blood lead concentrations above 5 and 10 micrograms/dl (0.24 and 0.48 mumol/l) respectively. The geometric mean maternal blood lead concentration was 3.65 micrograms/dl (0.18 mumol/l) in a random sample of mothers and 3.16 micrograms/dl (0.15 mumol/l) in mothers whose tap water lead concentrations were consistently below 2 micrograms/l (9.7 nmol/l). No mother in the study had a blood lead concentration above 25 micrograms/dl (1.21 mumol/l). An estimated 13% of infants were exposed via bottle feeds to tap water lead concentrations exceeding the World Health Organisation's guideline of 10 micrograms/l (48.3 nmol/l). CONCLUSIONS: Tap water lead and maternal blood led concentrations in the Loch Katrine water supply area have fallen substantially since the early 1980s. Maternal blood lead concentrations are well within limits currently considered safe for human health. Tap water lead is still a public health problem in relation to the lead exposure of bottle fed infants.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Delves H. T., Diaper S. J., Oppert S., Prescott-Clarke P., Periam J., Dong W., Colhoun H., Gompertz D. Blood lead concentrations in United Kingdom have fallen substantially since 1984. BMJ. 1996 Oct 5;313(7061):883–884. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7061.883d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobbie J. W. Silicon: its role in medicine and biology. Scott Med J. 1982 Jan;27(1):1–2. doi: 10.1177/003693308202700101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrow S. Falling sperm quality: fact or fiction? BMJ. 1994 Jul 2;309(6946):1–2. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6946.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulton M., Raab G., Thomson G., Laxen D., Hunter R., Hepburn W. Influence of blood lead on the ability and attainment of children in Edinburgh. Lancet. 1987 May 30;1(8544):1221–1226. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)92683-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halls D. J. Speeding up determinations by electrothermal atomic-absorption spectrometry. Analyst. 1984 Aug;109(8):1081–1084. doi: 10.1039/an9840901081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacey R. F., Moore M. R., Richards W. N. Lead in water, infant diet and blood: the Glasgow Duplicate Diet Study. Sci Total Environ. 1985 Mar 1;41(3):235–257. doi: 10.1016/0048-9697(85)90144-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millstone E., Russell J. Lead toxicity and public health policy. J R Soc Health. 1995 Dec;115(6):347–350. doi: 10.1177/146642409511500603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore M. R., Richards W. N., Sherlock J. G. Successful abatement of lead exposure from water supplies in the West of Scotland. Environ Res. 1985 Oct;38(1):67–76. doi: 10.1016/0013-9351(85)90073-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Needleman H. L., Gatsonis C. A. Low-level lead exposure and the IQ of children. A meta-analysis of modern studies. JAMA. 1990 Feb 2;263(5):673–678. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulos A., Beckman K. Human leucocyte cerebroside sulphate sulphatase. Clin Chim Acta. 1979 Jul 2;95(1):113–121. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(79)90343-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn M. J., Sherlock J. C. The correspondence between U.K. 'action levels' for lead in blood and in water. Food Addit Contam. 1990 May-Jun;7(3):387–424. doi: 10.1080/02652039009373904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz J., Otto D. Lead and minor hearing impairment. Arch Environ Health. 1991 Sep-Oct;46(5):300–305. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1991.9934391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoeppler M., Brandt K., Rains T. C. Contributions to automated trace analysis. Part II. Rapid method for the automated determination of lead in whole blood by electrothermal atomic-absorption spectrophotometry. Analyst. 1978 Jul;103(1228):714–722. doi: 10.1039/an9780300714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong S., Baghurst P., McMichael A., Sawyer M., Mudge J. Lifetime exposure to environmental lead and children's intelligence at 11-13 years: the Port Pirie cohort study. BMJ. 1996 Jun 22;312(7046):1569–1575. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7046.1569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]