Abstract

Panhandle PCR amplifies genomic DNA with known 5′ and unknown 3′ sequences from a template with an intrastrand loop schematically shaped like a pan with a handle. We used panhandle PCR to clone MLL genomic breakpoints in two pediatric treatment-related leukemias. The karyotype in a case of treatment-related acute lymphoblastic leukemia showed the t(4;11)(q21;q23). Panhandle PCR amplified the translocation breakpoint at position 2158 in intron 6 in the 5′ MLL breakpoint cluster region (bcr). The karyotype in a case of treatment-related acute myeloid leukemia was normal, but Southern blot analysis showed a single MLL gene rearrangement. Panhandle PCR amplified the breakpoint at position 1493 in MLL intron 6. Screening of somatic cell hybrid and radiation hybrid DNAs by PCR and reverse transcriptase-PCR analysis of the leukemic cells indicated that panhandle PCR identified a fusion of MLL intron 6 with a previously uncharacterized sequence in MLL intron 1, consistent with a partial duplication. In both cases, the breakpoints in the MLL bcr were in Alu repeats, and there were Alu repeats in proximity to the breakpoints in the partner DNAs, suggesting that Alu sequences were relevant to these rearrangements. This study shows that panhandle PCR is an effective method for cloning MLL genomic breakpoints in treatment-related leukemias. Analysis of additional pediatric cases will determine whether breakpoint distribution deviates from the predilection for 3′ distribution in the bcr that has been found in adult cases.

DNA topoisomerase II catalyzes transient cleavage and rejoining of both strands of the DNA double helix (1). Epipodophyllotoxins form a complex with the DNA and DNA topoisomerase II, decrease DNA rejoining, and cause chromosomal breakage (2). Epipodophyllotoxins and other DNA topoisomerase II inhibitors are associated with leukemias with translocations of a breakpoint cluster region (bcr) of the MLL gene at chromosome band 11q23 (3–10). One suggested model for the translocations involving MLL entails DNA topoisomerase II-mediated chromosomal breakage followed by fusion of DNA free ends from different chromosomes through DNA repair (11). A better understanding of the translocation mechanism may come through genomic breakpoint cloning in many other cases.

However, MLL genomic breakpoint cloning by PCR is difficult because MLL has myriad partner genes, and karyotype analysis does not detect the rearrangement or give information about potential translocation partners in one-third of cases (8). Other rearrangements result from partial duplication of several exons of the MLL gene (12–19). Panhandle PCR amplifies genomic DNA with known 5′ and unknown 3′ sequences and does not require specific primers for the many partner genes of MLL (20, 21). In the present study, we used panhandle PCR to surmount the problem of MLL genomic breakpoint cloning in two pediatric DNA topoisomerase II inhibitor-related leukemias. To validate the method, we first used panhandle PCR in a treatment-related leukemia in which the cytogenetic location of the partner DNA was known. We then applied the method to amplify a breakpoint involving unknown partner DNA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The Institutional Review Board at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia approved the use of leukemic marrow specimens for this research. Table 1 summarizes demographic, clinical, morphologic, and cytogenetic features for the two patients.

Detection of MLL Gene Rearrangements by Southern Blot Analysis.

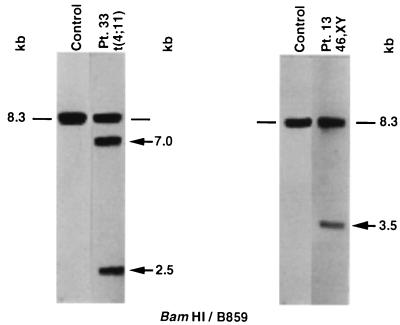

Genomic DNAs were examined by Southern blot analysis for rearrangement of the 8.3-kb BamHI fragment encompassing the bcr. We previously reported on the MLL gene rearrangement in the leukemia of patient 13 (8). Hybridization of BamHI-digested DNAs with the B859 MLL cDNA probe spanning exons 5–11 (22) was as described (8).

Panhandle PCR Amplification of MLL Genomic Breakpoints on der(11) Chromosomes.

High molecular weight genomic DNAs were isolated by ultracentrifugation on 4-M GITC-5.7M CsCl gradients (23). Five micrograms of genomic DNA containing known MLL sequence juxtaposed to unknown partner DNA was digested to completion with 40 units of BamHI (New England Biolabs) to create a 5′ overhang. The DNA was treated with 0.05 units of calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase (Boehringer Mannheim) at 37°C for 30 min and purified using a GENECLEAN III kit (Bio 101).

Next, a single-stranded 5′ phosphorylated oligonucleotide (5′-GAT CGA AGC TGG AGT GGT GGC CTG TTT GGA TTC AGG-3′) was ligated to the 3′ ends. The 4-base 5′ end of the oligonucleotide was complementary to the 5′ overhang of BamHI-digested DNA but would not reconstitute the BamHI site upon ligation. The 32-nucleotide 3′ end of the oligonucleotide was complementary to nucleotide positions 92–123 in the published sequence of MLL exon 5 (22). The 50-μl ligation reaction mixture contained 2.5 μg of DNA, a 50-fold molar excess of the 5′ phosphorylated oligonucleotide, 1 Weiss unit of T4 DNA ligase, and 1× ligase buffer (Boehringer Mannheim). Ligations were performed overnight at 16°C. The DNA again was purified using a GENECLEAN III kit.

To form the template, a 200-ng aliquot of the digested, ligated DNA was added to 1.75 units of Taq/Pwo DNA polymerase mix, 385 μM each dNTP, and PCR buffer at 1.1× final concentration in 45-μl reaction mixtures (Expand Long Template PCR System, Boehringer Mannheim). Reaction mixtures were preheated to 80°C before addition of the DNA to prevent nonspecific annealing and polymerization (21). Upon addition of the DNA, reaction mixtures were heated at 94°C for 1 min to make the template single-stranded by heat denaturation (21). The sense strand would become the template strand for PCR. Formation of the handle was accomplished during a 2-min ramp to 72°C and incubation at 72°C for 30 s, which promoted intrastrand annealing of the ligated oligonucleotide to the complementary sequence in MLL exon 5 and polymerase extension of the recessed 3′ end (21).

With the breakpoint junction and unknown partner DNA within an intrastrand loop or pan, the next step was to add primers and thermal cycle. Primer 1 from MLL exon 5 (5′-TCC TCC ACG AAA GCC CGT CGA G-3′) was upstream to the MLL sequence that was complementary to the ligated oligonucleotide. Primer 2, also from MLL exon 5 (5′-TCA AGC AGG TCT CCC AGC CAG CAC-3′), was between the MLL sequence that was complementary to the ligated oligonucleotide and the breakpoint junction. The 50-μl final PCR mixtures contained 12.5 pmol of each primer, 350 μM each dNTP, and 1× PCR buffer. After initial denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, 10 cycles at 94°C for 10 s and 10 cycles at 68°C for 5 min and 20 cycles at 94°C for 10 s and 68°C for 5 min (increment 20 s/cycle) were utilized, followed by final elongation at 68°C for 7 min. Nested PCR was performed using the same conditions and a 1-μl aliquot of the initial PCR as template DNA. MLL exon 5 primers for nested PCR were 5′-A GCT GGA TCC GGA AAA GAG TGA AGA AGG GAA TGT CTC GG-3′ and 5′-A GCT GGA TCC GTG GTC ATC CCG CCT CAG CCA C-3′.

Subcloning and Sequencing Panhandle PCR Products.

Panhandle PCR products from leukemia DNAs were size-separated in 2% agarose gels and subcloned into the BamHI site of pBluescript SK II (Stratagene). Individual genomic subclones were sequenced by automated methods to identify the breakpoints and characterize the partner DNAs.

Direct Sequencing of MLL Genomic Breakpoints.

Genomic sequences of panhandle PCR products were used in the design of primers encompassing the respective breakpoints. Two hundred nanograms of genomic DNA from the leukemic cells were amplified in 50-μl PCR mixtures with 0.5 units of Taq Gold DNA polymerase, 250 μM each dNTP, PCR buffer at 1× final concentration (Perkin–Elmer), and 5 pmol each primer. For the leukemia of patient 33 with the t(4;11), forward and reverse primers were 5′-GCA CAG TGA CAC ACA GTT GCT-3′ and 5′-CAA CAC CCC AAG ACC TTG TC-3′, respectively, and would yield a 336-bp product. In the case of patient 13, forward and reverse primers were 5′-GTA ATC CTA GCT ACT TGG GAG GCT-3′ and 5′-TGA GGG ACT TCA AAG AAT TAC ACA-3′, respectively, and would give a 288-bp product. After initial denaturation and Taq Gold activation at 95°C for 10 min, 35 cycles at 94°C for 15 s, 55°C for 15 s, and 72°C for 1 min were utilized, followed by a final elongation at 72°C for 10 min. Products of reactions performed in duplicate for each primer set were isolated from a 1.5% agarose gel using a GENECLEAN II kit. Approximately 100 ng of pooled, purified PCR products was used for each sequencing reaction. Sequencing was performed in both directions by automated methods.

Localization of Partner DNAs.

To determine the chromosomal location of the partner DNA in the case of patient 33, a panel of radiation hybrid DNAs was screened by PCR. In the case of patient 13, panels of somatic cell hybrid DNAs and radiation hybrid DNAs were screened by PCR. The Stanford G3 radiation hybrid panel (Research Genetics, Huntsville, AL) and somatic cell hybrid DNAs from the Bios (New Haven, CT) panel were used in these experiments (Bios Laboratories).

The 20-μl PCR mixtures contained 25 ng of DNA, 0.5 unit of AmpliTaq DNA polymerase, 250 μM each dNTP, PCR buffer at 1× final concentration (Perkin–Elmer), and 5 pmol of each primer. In the case of patient 33, forward and reverse primer sequences were 5′-GCC CAA GAG GAA AGC ATA AA-3′ and 5′-TGA AAA CAA GGA GGA ACA GGA-3′, respectively, and would give a 159-bp product. In the case of patient 13, forward and reverse primer sequences were 5′-GGT GCA ACA TTA AGA CCT TGG-3′ and 5′-ATC AAA TGA GGA GGC CAC AG-3′, respectively, and would give a 222-bp product. After initial denaturation at 94°C for 9 min, 35 cycles at 94°C for 1 min, 55°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 2 min were performed, followed by a final elongation at 72°C for 7 min. PCR mixtures were electrophoresed in VisiGel Separation Matrix (Stratagene).

For the somatic hybrid screen, reaction mixtures yielding products were compared with the known human chromosome complement of the somatic hybrid panel to determine the location of the partner DNA. For the radiation hybrid screens, reactions yielding products and reactions without products were scored as 1 and 0, respectively. Results were submitted to the radiation hybrid server of the Stanford Human Genome Center to determine the locations of the partner DNAs.

Reverse Transcriptase–PCR (RT-PCR) Analysis.

RT-PCR analysis was performed to evaluate whether the fusion in the acute myeloid leukemia (AML) of patient 13 was an MLL partial duplication. We used the Superscript Preamplification System and an antisense primer from MLL exon 3 (12, 13) for synthesis of first strand cDNA from 1 μg of total RNA by the gene-specific primer method (GIBCO/BRL). A β-actin antisense primer (5′-CAG AGG CGT ACA GGG ATA GC-3′) was used to synthesize first strand cDNA as a positive control.

The 100-μl initial RT-PCR mixtures contained 2-μl first strand cDNA, 2.5 units of AmpliTaq DNA polymerase, 200 μM each dNTP, PCR buffer at 1× final concentration (Perkin–Elmer), and 20 pmol each primer. The forward and reverse primers from MLL exons 5 and 3, respectively, have been described (12, 13). For the β-actin control, the forward and reverse primers were 5′-GGC ATC CTC ACC CTG AAG TA-3′ and 5′-CAG AGG CGT ACA GGG ATA GC-3′, respectively, and would yield a 250-bp product. After initial denaturation at 94°C for 5 min, 35 cycles at 94°C for 1 min, 53°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min were performed, followed by a final elongation at 72°C for 7 min. Nested RT-PCR were performed for MLL but not for β actin. A 1-μl aliquot of the initial RT-PCR mixture was used as template, and sense and antisense primers were from MLL exons 6 and 3, respectively (12, 13). Conditions were the same as for initial RT-PCR except that only 30 cycles were performed, and the annealing temperature was 60°C.

RT-PCR mixtures were electrophoresed in VisiGel Separation Matrix (Stratagene) to visualize the products. Products of reactions performed in triplicate were electrophoresed in 2% agarose and gel-purified for sequencing using a GENECLEAN III kit. Twenty-five nanograms of purified RT-PCR products was used for direct automated sequencing with the same forward and reverse MLL primers as those used for nested RT-PCR.

RESULTS

Panhandle PCR Amplifies Genomic Translocation Breakpoint in Treatment-Related Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL) with t(4;11)(q21;q23). Southern blot analysis of the ALL of patient 33 with the t(4;11)(q21;q23) revealed 7- and 2.5-kb rearrangements with the B859-BamHI probe-restriction enzyme combination (Fig. 1). Fig. 2A shows the products of three separate panhandle PCRs. Panhandle PCR products 2620 bp in size indicated that the 2.5-kb restriction fragment on Southern blot analysis was from the der(11) chromosome. Automated sequencing of three subclones of these products, 38–1, 38–2, and 38–4, identified the MLL genomic breakpoint at nucleotide 2158 in intron 6 in the 5′ bcr (Fig. 2B). For further confirmation of the breakpoint sequence, we amplified genomic DNA from the leukemic cells with a primer set encompassing the translocation breakpoint. Direct sequencing verified that nucleotide 2158 was the breakpoint in the MLL bcr.

Figure 1.

Identification of rearrangements within the MLL bcr in treatment-related leukemias by Southern blot analysis. BamHI-digested DNAs were hybridized with B859 MLL cDNA probe-spanning exons 5–11 (22). The 8.3-kb fragment is from the unrearranged allele (dash marks). Control DNAs show a germline pattern. Numbers above the lanes correspond to patient numbers in Table 1. Arrows show rearrangements. Southern blot analysis in the case of patient 13 has been described (8).

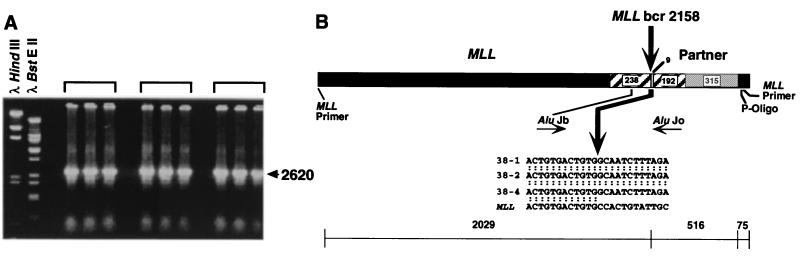

Figure 2.

(A) Panhandle PCR products from der(11) chromosome of t(4;11)(q21;q23) in treatment-related ALL of patient 33. Brackets indicate separate panhandle PCRs where identical 2620-bp products were obtained. (B) Sequence of t(4;11) breakpoint junction in individual subclones, 38–1, 38–2, and 38–4, from panhandle PCR. The 5′ 2029 bp include MLL forward nested primer and MLL bcr sequence; 516 bp of 3′ sequence are partner DNA, and 75 bp of 3′ sequence extend from ligated oligonucleotide (P-Oligo) through reverse nested primer. Comparison with normal sequence identified the breakpoint at nucleotide 2158 in MLL intron 6 (bold arrow). AluJ repeats in MLL and partner DNA are shown. Sequences were the same in all three subclones.

Sequences of the breakpoint and the partner DNA 3′ of the breakpoint were the same in all three subclones. The breakpoint in MLL was within an Alu element of the J subfamily (Fig. 2B). Five hundred sixteen base pairs of sequence 3′ of the breakpoint represented partner DNA, followed by sequences of the ligated oligonucleotide and the reverse primer used for nested PCR. The partner DNA also contained an AluJ that began 9 bp downstream from the translocation breakpoint (Fig. 2B). The more 3′ sequence of the partner DNA was rich in short poly-A and poly-T repeats.

Consistent with the karyotype, screening of the Stanford G3 radiation hybrid panel with PCR primers from the partner DNA indicated that the nearest linked marker to the partner DNA was D4S1542 at chromosome band 4q21. These results validated the panhandle PCR method in a treatment-related leukemia in which the cytogenetic location of the partner DNA was known.

Although the leukemia showed a t(4;11)(q21;q23) translocation, the nonrepetitive partner DNA sequences did not share homology with known genomic sequences of AF-4. However, screening of radiation hybrid panel DNAs previously indicated that the nearest linked marker to the AF-4 gene was also D4S1542 (24), suggesting that the partner DNA in the treatment-related ALL was derived from either AF-4 or from a genomic sequence in close proximity to AF-4.

Panhandle PCR Identifies MLL Partial Duplication in Treatment-Related AML with 46, XY Karyotype.

In the AML in which the karyotype was 46, XY, Southern blot analysis revealed a single 3.5-kb rearrangement in BamHI-digested DNA (8) (Fig. 1). Fig. 3A shows panhandle PCR products 3446 bp in size, consistent with the single rearrangement on Southern blot analysis. Sequencing of subclone 35–1 identified the breakpoint at position 1493 in intron 6 of the MLL bcr. PCR amplification of genomic DNA from the leukemic cells with a primer set encompassing the breakpoint and direct genomic sequencing confirmed that nucleotide 1493 was the rearrangement breakpoint in the MLL bcr.

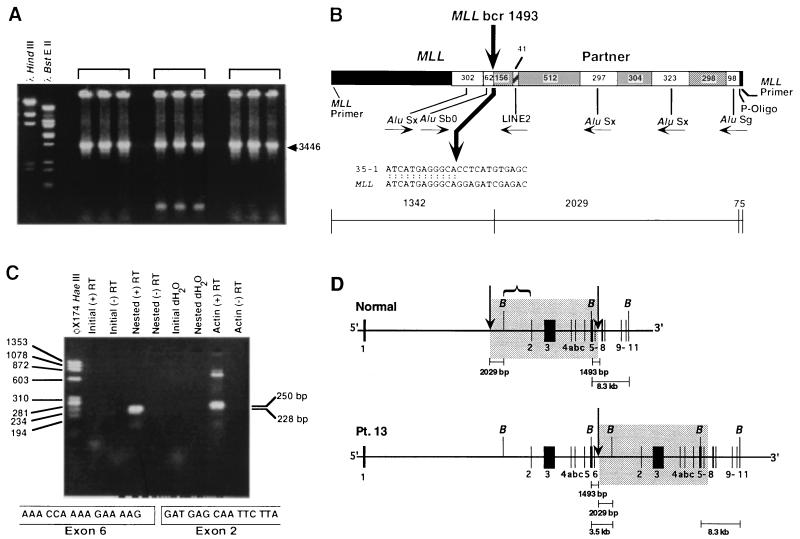

Figure 3.

(A) Panhandle PCR products from treatment-related AML of patient 13 involving unknown partner DNA. Brackets show three separate reactions in which identical 3446-bp products were obtained. (B) Breakpoint junction in subclone 35–1 from panhandle PCR. Comparison with normal sequence identified the breakpoint in MLL bcr at nucleotide 1493 in intron 6 (bold arrow). The 5′ 1342 bp include MLL forward nested primer and MLL bcr sequence to nucleotide 1493. Somatic cell hybrid and radiation hybrid screens and RT-PCR analysis (c.f. Fig. 3C) showed that 2029 bp of sequence 3′ of the breakpoint originated from a previously uncharacterized region of MLL intron 1. AluS repeats in MLL bcr and MLL intron 1 are shown. Nonrepetitive sequences are gray. (C) RT-PCR analysis of total RNA from leukemic cells of patient 13 indicating MLL partial duplication. Nested reactions with sense and antisense primers from MLL exons 6 and 3, respectively, gave a single 228-bp product (Upper). Direct sequencing of the products of three reactions revealed an in-frame fusion of exon 6 to exon 2 (Lower). Reactions using β-actin primers (positive control) and RNA negative control (dH2O) are shown (Upper). (D) Comparison of normal MLL genomic structure [Upper, adapted from Rasio (27)] with MLL partial duplication in treatment-related AML of patient 13 (Lower). Arrows indicate breakpoint positions in MLL introns 6 and 1 in AML of patient 13. The intron 1 breakpoint, which produced a 3.5-kb rearranged BamHI fragment, was 5′ of the intron 1 BamHI site. Box indicates duplicated region. Bracket shows region of involvement 3′ of intron 1 BamHI site, resulting in rearranged BamHI fragments of larger sizes in previously reported partial duplications (12, 14, 16, 18).

The breakpoint in MLL intron 6 was within an AluS repeat (Fig. 3B). Two thousand twenty-nine base pairs of sequence 3′ of the breakpoint were from partner DNA, followed by sequences of the ligated oligonucleotide and the reverse primer used for nested PCR. The partner DNA contained four unique sequence regions, one LINE2 element, and three additional AluS repeats. The breakpoint in the partner DNA was in a unique sequence region (Fig. 3B).

Single rearrangements on Southern blot analysis sometimes indicate partial duplication of several exons of the MLL gene (12–19). However, the partner DNA did not share homology with known genomic sequences of MLL, and the small size of the rearranged BamHI fragment (Fig. 1) was not consistent with other partial duplications analyzed with BamHI (12, 14, 16, 18). To determine the chromosomal location of the partner DNA, panels of somatic cell hybrid DNAs and radiation hybrid DNAs were screened by PCR. Amplification of a PCR product from cell line 1049 in the somatic cell hybrid panel (Bios) indicated that the partner DNA was on human chromosome 11 (data not shown). PCR amplification of radiation hybrid lines in the Stanford G3 radiation hybrid panel showed that the partner sequence was in the same bin as the framework marker D11S2060 at chromosome band 11q23.3.

We performed RT-PCR analysis on total RNA from the leukemic cells to evaluate whether the fusion was an MLL partial duplication. Nested RT-PCRs with sense and antisense primers from MLL exon 6 and exon 3, respectively, gave a single 228-bp product (Fig. 3C). Direct sequencing of the products of three separate nested RT-PCRs revealed an in-frame fusion of exon 6 to exon 2 (Fig. 3C), indicating that panhandle PCR identified an MLL partial duplication that joined intron 6 with intron 1 2029 bp upstream of the intron 1 BamHI restriction site (Fig. 3D).

DISCUSSION

We show an application of panhandle PCR to amplify genomic breakpoints in treatment-related leukemias with MLL gene rearrangements. The study demonstrates that panhandle PCR is an effective method to clone translocation breakpoints. Rearrangement sizes on Southern blot analysis with the BamHI-B859 combination determined elongation times for panhandle PCR. Additional breakpoint mapping by Southern blot analysis was unnecessary either for design of primers or for design of panhandle PCR conditions. Thus panhandle PCR is practical in treatment-related leukemias with limited DNAs. We obtained panhandle PCR products of sizes predicted by Southern blot analysis of the MLL bcr. Also as predicted, there were no panhandle PCR products from the normal MLL allele because the elongation segment targeted templates smaller than 8.3 kb. We confirmed each translocation breakpoint by the independent method of direct genomic sequencing. This initial success suggests that panhandle PCR will simplify the cloning of additional MLL genomic breakpoints.

Panhandle PCR amplified the translocation breakpoint at position 2158 in the MLL bcr in the treatment-related ALL with cytogenetic t(4;11) translocation. Although AF-4 is the most common partner gene of MLL in leukemias with t(4;11) translocations, most known sequence information on AF-4 is limited to the cDNA (25) whereas AF-4 intronic sequences generally are uncharacterized. The sequence of the partner DNA in the treatment-related ALL did not share homology with known sequences of AF-4. Nonetheless, the closest framework marker to the AF-4 gene (24) and to the partner DNA in the treatment-related ALL was the same. These results suggest that panhandle PCR amplified either a previously uncharacterized intronic region of the AF-4 gene or, alternatively, another genomic region in close proximity to AF-4.

In the treatment-related karyotype-negative AML of patient 13, Southern blot analysis detected a single 3.5-kb rearrangement, and panhandle PCR amplified a product 3446 bp long. Panhandle PCR identified the rearrangement breakpoint at position 1493 in intron 6 in the MLL bcr. Gill–Super et al. described deletion of the 3′ bcr during translocation as one explanation for single MLL gene rearrangements (26), but this was not the explanation in the case of patient 13. Another explanation for single MLL gene rearrangements in karyotype-negative de novo leukemias and de novo leukemias with trisomy of chromosome 11 is partial duplication of MLL exons 2–6 or 2–8 (12–19). However, most previously reported partial duplications fused MLL intron 6 or intron 8 with intron 1 downstream of the BamHI site in intron 1. This results in rearranged BamHI fragments of much larger size because the distance between the BamHI site in MLL intron 1 and the next BamHI site in MLL exon 5 is 18.5 kb (Fig. 3D) (12, 14, 16, 18, 27). Moreover, the sequence downstream of the breakpoint in the karyotype-negative treatment-related AML did not share homology with known genomic sequences of MLL.

Nonetheless, screening of somatic cell hybrid and radiation hybrid DNAs by PCR indicated that the DNA downstream of the intron 6 genomic breakpoint originated from chromosome band 11q23.3. Together with the results from Southern blot analysis, the chimeric mRNA on RT-PCR proved that panhandle PCR identified a fusion of MLL intron 6 with MLL intron 1 upstream of the intron 1 BamHI restriction site. The intron 1 breakpoint location differs from the breakpoints in most other partial duplications, which are 3′ of the BamHI site (Fig. 3D) (12, 14, 16, 18). Sequencing defined the 2029 bp of MLL intron 1 immediately upstream of the BamHI site, which previously had not been characterized. MLL partial duplications have not been found before in treatment-related leukemias.

In each leukemia in this study, the breakpoint in the MLL bcr was within an Alu repeat. Furthermore, there were homologous Alu repeats of the same subfamilies in the recombining partner DNAs in proximity to each breakpoint. Alu sequences in other genes allow homologous recombination (28). As Schichman et al. suggested, these findings further argue that homologous Alu repeats in MLL and partner DNAs may be important for these rearrangements (13). Indeed, another partial duplication in a de novo leukemia involved the same MLL intron 6 AluS repeat as the treatment-related AML of patient 13 in the present study (16).

In contrast with the clustering of treatment-related breakpoints in the 3′ bcr that has been found in adults (6), the breakpoint locations determined by panhandle PCR in the pediatric treatment-related leukemias were both in MLL intron 6 in the 5′ bcr. Both pediatric patients received dactinomycin (Table 1). Cloning of additional breakpoints by panhandle PCR will address whether specific chemotherapy agents, combined modality therapy, or patient age are determinants of breakpoint location. Molecular cloning of MLL genomic breakpoints previously has been difficult. Panhandle PCR provides a new tool to understand the molecular epidemiology and pathogenesis of leukemias with MLL gene rearrangements.

Table 1.

Treatment-related leukemia

| Patient | 13 | 33 |

| Race/gender | W/M | W/F |

| Primary cancer | Embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma | Alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma |

| Age at diagnosis of primary cancer | 10 yr, 3 mo | 9 yr, 11 mo |

| Primary cancer chemotherapy | VCR, AMD, CPM, MTX, HC, Ara-C | VCR, AMD, CPM, IFOS, VP16 |

| Prior radiation | Yes | Yes |

| Interval to treatment-related leukemia (months) | 60 | 15 |

| French–American–British morphology | M4 | L1 |

| Karyotype | 46,XY[18] | 46,XX,t(4;11)(q21;q23)[4]/46,XX[3] |

W, white; M, male; F, female; VCR, vincristine; AMD, dactinomycin; CPM, cyclophosphamide; MTX, methotrexate; HC, hydrocortisone; Ara-C, cytosine arabinoside; IFOS, ifosphamide; VP16, etoposide.

Acknowledgments

We thank Margaret Masterson and Bruce Himelstein for contributing patient materials and clinical information, Erik Sulman and Peter White for helpful discussions, and Terence Williams for figure preparation. C.A.F. was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant 1R29CA66140-02, American Cancer Society Grant DHP143, a Leukemia Society of America Scholar Award (1996–2001), the National Childhood Cancer Foundation, the National Leukemia Research Association Grant in Memory of Maria Bernabe Garcia, and the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia High Risk/High Impact Grant. C.S.K. was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant 5R25CA4009. P.C.N. was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant CA42232.

ABBREVIATIONS

- bcr

breakpoint cluster region

- AML

acute myeloid leukemia

- RT-PCR

reverse transcriptase–PCR

- ALL

acute lymphoblastic leukemia

Note Added in Proof

Since the original submission, we performed RT-PCR analysis on total RNA from the leukemic cells of patient 33 and amplified and sequenced an in-frame MLL exon 6–AF-4 chimeric product, proving that the partner DNA in the t(4;11) was previously uncharacterized AF-4 intronic sequence.

Footnotes

References

- 1.Berger J M, Gamblin S J, Harrison S C, Wang J C. Nature (London) 1996;379:225–233. doi: 10.1038/379225a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Corbett A, Osheroff N. Chem Res Toxicol. 1993;6:585–597. doi: 10.1021/tx00035a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pui C-H, Hancock M L, Raimondi S C, Head D R, Thompson E, Wilimas J, Kun L E, Bowman L C, Crist W M, Pratt C B. Lancet. 1990;336:417–421. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)91956-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pui C-H, Ribeiro R C, Hancock M L, Rivera G K, Evans W E, Raimondi S C, Head D R, Behm F G, Mahmoud M H, Sandlund J T, Crist W M. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1682–1687. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199112123252402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Winick N, McKenna R W, Shuster J J, Schneider N R, Borowitz M J, Bowman W P, Jacaruso D, Kamen B A, Buchanan G R. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:209–217. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.2.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Broeker P, Super H, Thirman M, Pomykala H, Yonebayashi Y, Tanabe S, Zeleznik-Le N, Rowley J. Blood. 1996;87:1912–1922. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Felix C A, Winick N J, Negrini M, Bowman W P, Croce C M, Lange B J. Cancer Res. 1993;53:2954–2956. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Felix C, Hosler M, Winick N, Masterson M, Wilson A, Lange B. Blood. 1995;85:3250–3256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pedersen-Bjergaard J. Leukemia Res. 1992;16:61–65. doi: 10.1016/0145-2126(92)90102-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pedersen-Bjergaard J, Philip P. Blood. 1991;78:1147–1148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Felix C, Lange B, Hosler M, Fertala J, Bjornsti M-A. Cancer Res. 1995;55:4287–4292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schichman S, Caligiuri M, Gu Y, Strout M, Canaani E, Bloomfield C, Croce C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:6236–6239. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.13.6236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schichman S, Caligiuri M, Strout M, Carter S, Gu Y, Canaani E, Bloomfield C, Croce C. Cancer Res. 1994;54:4277–4280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Caligiuri M A, Strout M P, Schichman S A, Mrozek K, Arthur D C, Herzig G P, Baer M R, Schiffer C A, Heinonen K, Knuutila S, Nousiainen T, Ruutu T, Block A M W, Schulman P, Pedersen-Bjergaard J, Croce C M, Bloomfield C D. Cancer Res. 1996;56:1418–1425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Caligiuri M A, Strout M P, Oberkircher A R, Yu F, de la Chapelle A, Bloomfield C D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3899–3902. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.So C W, Ma Z G, Price C M, Dong S, Chen S J, Gu L J, So C K C, Wiedemann L M, Chan L C. Cancer Res. 1997;57:117–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu M, Honoki K, Andersen J, Paietta E, Nam D, Yunis J. Leukemia. 1996;10:774–780. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamamoto K, Hamaguchi H, Nagata K, Kobayashi M, Taniwaki M. Am J Hematol. 1997;55:41–45. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8652(199705)55:1<41::aid-ajh8>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakao M, Yokota S, Iwai T, Kaneko H, Horiike S, Kashima K, Sonoda Y, Fujimoto T, Misawa S. Leukemia. 1996;10:1911–1918. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones D, Winistorfer S. PCR Methods Appl. 1993;2:197–203. doi: 10.1101/gr.2.3.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones D. PCR Methods Appl. 1995;4:S195–S201. doi: 10.1101/gr.4.5.s195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gu Y, Nakamura T, Alder H, Prasad R, Canaani O, Cimino G, Croce C, Canaani E. Cell. 1992;71:701–708. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90603-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Felix C A, Poplack D G, Reaman G H, Steinberg S M, Cole D E, Taylor B J, Begley C G, Kirsch I R. J Clin Oncol. 1990;8:431–442. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1990.8.3.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stewart E A, McKusick K B, Aggarwal A, Bajorek E, Brady S, et al. Genome Res. 1997;7:422–433. doi: 10.1101/gr.7.5.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakamura T, Alder H, Gu Y, Prasad R, Canaani O, Kamada N, Gale R P, Lange B, Crist W M, Nowell P C, Croce C M, Canaani E. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:4631–4635. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.10.4631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Super H J G, McCabe N R, Thirman M J, Larson R A, LeBeau M M, Pedersen-Bjergaard J, Philip P, Diaz M O, Rowley J D. Blood. 1993;82:3705–3711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rasio D, Schichman S A, Negrini M, Canaani E, Croce C M. Cancer Res. 1996;56:1766–1769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schmid C W. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1996;53:283–319. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60148-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]