Abstract

The interactions between calmodulin, inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (InsP3), and pure cerebellar InsP3 receptors were characterized by using a scintillation proximity assay. In the absence of Ca2+, 125I-labeled calmodulin reversibly bound to multiple sites on InsP3 receptors and Ca2+ increased the binding by 190% ± 10%; the half-maximal effect occurred when the Ca2+ concentration was 184 ± 14 nM. In the absence of Ca2+, calmodulin caused a reversible, concentration-dependent (IC50 = 3.1 ± 0.2 μM) inhibition of [3H]InsP3 binding by decreasing the affinity of the receptor for InsP3. This effect was similar at all Ca2+ concentrations, indicating that the site through which calmodulin inhibits InsP3 binding has similar affinities for calmodulin and Ca2+-calmodulin. Calmodulin (10 μM) inhibited the Ca2+ release from cerebellar microsomes evoked by submaximal, but not by maximal, concentrations of InsP3. Tonic inhibition of InsP3 receptors by the high concentrations of calmodulin within cerebellar Purkinje cells may account for their relative insensitivity to InsP3 and limit spontaneous activation of InsP3 receptors in the dendritic spines. Inhibition of InsP3 receptors by calmodulin at all cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations, together with the known redistribution of neuronal calmodulin evoked by protein kinases and Ca2+, suggests that calmodulin may also allow both feedback control of InsP3 receptors and integration of inputs from other signaling pathways.

Keywords: cerebellum, scintillation proximity assay

Calmodulin is a ubiquitous and highly conserved Ca2+-binding protein that mediates many of the effects of increases in cytosolic Ca2+ concentration on such diverse cellular processes as enzyme and ion channel activity, cytoskeletal organization, and progression through the cell cycle (1). In addition, calmodulin is one means whereby the activities of different intracellular signaling pathways are coordinated: both formation and degradation of cyclic AMP, for example, are regulated by Ca2+–calmodulin, as are the activities of several protein kinases and phosphatases. Calmodulin is also involved in some of the mechanisms that control the increases in cytosolic Ca2+ concentration evoked by extracellular stimuli. These targets include certain plasma membrane Ca2+ pumps (2), ryanodine receptors (3), cyclic nucleotide-gated Ca2+ channels (4), and the Ca2+ channels encoded by the trp and trpl genes (5–7), which mediate Ca2+ entry evoked by receptors linked to formation of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (InsP3).

Many ion channels are modulated by Ca2+–calmodulin. The effects are usually mediated by phosphorylation (8) and less commonly by direct binding of Ca2+–calmodulin to the channel (4, 7). In ryanodine receptors, which are intracellular Ca2+ channels with structural and functional similarities to InsP3 receptors (9), calmodulin binds to multiple sites (10) and thereby exerts complex effects on channel activity (3, 11). The receptors for InsP3 are more widely distributed than ryanodine receptors, and in many cells they mediate both the initial release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores and the subsequent propagation of a regenerative Ca2+ signal evoked by extracellular stimuli (12). Both ryanodine (13, 14) and InsP3 (15) receptors are phosphorylated by Ca2+–calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII), although the functional consequences are unclear (13, 14, 16, 17). However, whereas calmodulin binding to ryanodine receptors is known to regulate their activity (18), calmodulin has been reported to inhibit (19), stimulate (20), or have no effect (11) on InsP3-stimulated Ca2+ release.

Here we use a scintillation proximity assay (SPA)¶ to demonstrate that calmodulin in both its Ca2+-bound and Ca2+-free forms binds directly to pure cerebellar InsP3 receptors. Ca2+-independent binding of calmodulin inhibits both InsP3 binding and InsP3-evoked Ca2+ mobilization, and it provides a means whereby the changes in free calmodulin concentration known to occur during stimulation of neurons (1) may regulate the sensitivity of InsP3 receptors.

METHODS

InsP3 receptors were purified from rat cerebella by sequential heparin and Con A affinity chromatography (21), rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C. From both silver staining of denaturing gels and the stoichiometry of InsP3 binding (1.3 ± 0.4 nmol/mg of protein, n = 5), the receptor preparations were shown to be pure. Sucrose density gradient centrifugation confirmed the tetrameric structure of the purified receptors. InsP3 receptors from six independent purifications were used.

In SPA, only radioligand bound to receptors tethered to the surface of the SPA bead is detected by the scintillant immobilized within it (22), allowing binding to be measured without separation of bound from free ligand. The method is therefore suitable for both characterization of low-affinity binding and real-time analyses of the interactions between ligands and their receptors. Because the only two residues of the type 1 InsP3 receptor that are glycosylated are closely juxtaposed and lie within the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum (23), tethering the receptor through these residues to lectin-coated SPA beads is unlikely to interfere with analyses of the binding of cytosolic ligands. Purified InsP3 receptors (40 μg/ml) were coupled to wheat-germ agglutinin-coated SPA beads (1.25 or 40 mg/ml) as previously described (24). The receptor-beads were then washed by centrifugation (20,000 × g, 60 s) and resuspended in medium containing 20 mM piperazine-N,N′-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid) (Pipes; pH 7 at 2°C), 1 mM EGTA, 5 mM K2HPO4, 0.1% Surfact-Amps X-100 (Pierce and Warriner, Chester, U.K.), 1% BSA (fraction V, Sigma), and 0–1 mM CaCl2. The free Ca2+ concentration of the medium ([Ca2+]m) was measured with fura 2, using the methods and temperature correction previously reported (25).

Binding of [3H]InsP3 (2–3 nM; 54 Ci/mmol; Amersham; 1 Ci = 37 GBq) to the InsP3 receptor-beads (10 mg/ml) was performed in microcentrifuge tubes immersed in iced water. Bound radioactivity was determined by counting samples (200 μl) for 60 s, and nonspecific binding (typically 5% of total binding) was measured in the presence of 1 μM unlabeled InsP3 (American Radiolabeled Chemicals, St. Louis). Specific binding of [3H]InsP3 was typically 3,000 cpm per incubation. [3H]InsP3 binding to cerebellar membranes was characterized by using a centrifugation method (24) in the same medium used for SPA analyses. Our previous study established that the affinity of the receptor for InsP3 and heparin, the kinetics of InsP3 binding, and the specificity of the receptor were similar whether measured by SPA or by conventional methods (24).

Bovine brain calmodulin (Calbiochem) was radiolabeled with 125I, using the Bolton and Hunter reagent, to a specific activity of 1.1 Ci/μmol. To minimize direct binding of 125I-labeled calmodulin (125I-calmodulin) to SPA beads, the concentration of SPA beads in the coupling reaction was reduced from that used for [3H]InsP3 binding to 1.25 mg/ml; the higher density of InsP3 receptors per bead then allowed fewer beads (0.625 mg/ml) to be used in binding assays. In parallel experiments using the conditions described previously (24), [3H]InsP3 binding was indistinguishable when determined at high [Kd = 10.3 ± 1.2 nM, Hill coefficient (nH) = 0.97 ± 0.06 nM; n = 4] or low (Kd = 11.0 ± 1.4 nM, nH = 1.0 ± 0.14; n = 5) densities of InsP3 receptors per bead. The methods used to measure 125I-calmodulin (2–3 nM) binding to InsP3 receptor-beads were otherwise the same as those used for [3H]InsP3 binding. Nonspecific 125I-calmodulin binding (typically 20% of total binding) was measured in the presence of 50 μM unlabeled bovine brain calmodulin. Specific binding of 125I-calmodulin was typically 2,000–4,000 cpm per incubation. No specific [3H]InsP3 or 125I-calmodulin binding was detected to SPA beads alone. Counting efficiencies for 125I (22.1%) and 3H (10.4%) were established by using standard SPA beads (22).

Equilibrium-competition binding results were fitted to logistic equations (24) and kinetics results were fitted to combinations of exponential equations using least-squares curve-fitting (Kaleidagraph, Synergy Software, Reading, PA).

Cerebellar microsomes were prepared (26) in media supplemented with protease inhibitors (100 μM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 μM pepstatin, 0.02 unit/ml aprotinin, 20 μg/ml soybean trypsin inhibitor, 100 μM captopril) and stored in liquid nitrogen. For 45Ca2+ flux assays, microsomes were resuspended (125 μg of protein per ml) in loading medium (LM) at 20°C containing 100 mM KCl, 20 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 20 mM Hepes (pH 7), 240 μM EGTA, 64 μM CaCl2, 1.5 mM ATP, 5 mM phosphocreatine, 1 unit/ml creatine kinase, and 8 μCi/ml 45CaCl2; the free [Ca2+] of LM, determined using fura 2, was 200 nM (25). After 5 min at 20°C, during which the microsomes actively accumulated 45Ca2+, 200-μl samples were added to appropriate concentrations of InsP3, and after a further 45 s, the 45Ca2+ content of the microsomes was determined after rapid filtration through Whatman GF/C filters (25).

RESULTS

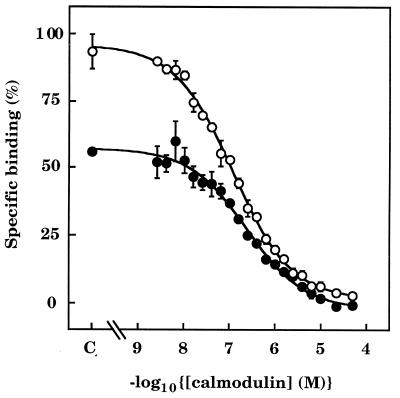

Specific and reversible binding of 125I-calmodulin to pure cerebellar InsP3 receptors was detected by SPA in nominally Ca2+-free medium ([Ca2+]m ≈ 2 nM; Fig. 1A), whereas previous studies with conventional methods had revealed only Ca2+-dependent interactions (27). Addition of Ca2+ ([Ca2+]m ≈ 30 μM) caused a 1.9 ± 0.1-fold increase (n = 12) in 125I-calmodulin binding to InsP3 receptors, which was reversed by addition of EGTA (40 mM; Fig. 1A). The half-maximal effect of Ca2+ (EC50) occurred when [Ca2+]m was 184 ± 14 nM (n = 3; Fig. 1B). The rates of 125I-calmodulin association with (Fig. 1A), and dissociation from (Fig. 1C), InsP3 receptors were slow and multiphasic in both the absence (≈2 nM) and presence (≈30 μM) of Ca2+. In equilibrium competition binding experiments, half-maximal displacement of 125I-calmodulin (IC50) occurred when the calmodulin concentration was 288 ± 72 nM (n = 3) in Ca2+-free medium and 117 ± 6 nM (n = 3) in Ca2+-containing medium (Fig. 2). The competition curves were shallow in both the absence (Hill coefficient = 0.68 ± 0.09) and presence (Hill coefficient = 0.67 ± 0.09) of Ca2+, consistent with the labeling of multiple calmodulin-binding sites in both situations.

Figure 1.

Reversible binding of 125I-calmodulin to pure InsP3 receptors in the absence and presence of Ca2+. (A) The time course of specific binding of 125I-calmodulin (3 nM) to SPA-InsP3 receptor beads is shown, first in nominally Ca2+-free medium ([Ca2+]m ≈ 2 nM), then after addition of Ca2+ ([Ca2+]m ≈ 30 μM), and finally after addition of EGTA (40 mM) to restore [Ca2+]m to ≈2 nM. The main panel illustrates results from a single experiment, representative of three. Equilibrium binding of 125I-calmodulin in Ca2+-free medium (n = 12), Ca2+-containing medium (n = 12), and after addition of EGTA (n = 3) are shown in the histogram (means ± SEM). (B) The stimulatory effect of [Ca2+]m on specific 125I-calmodulin binding is plotted as a percentage of the maximal effect, which was obtained when [Ca2+]m was ≈30 μM. The 0 and 100% values were both derived by extrapolation of the curves. Results are means ± SEM of three independent experiments. (C) Dissociation of 125I-calmodulin from InsP3 receptors is shown after addition of calmodulin (50 μM) to SPA-InsP3 receptor beads that had equilibrated (3 h) with 125I-calmodulin (3 nM) in the absence (•, [Ca2+]m ≈ 2 nM) or presence (○, [Ca2+]m ≈ 30 μM) of Ca2+. Results are plotted on a semilogarithmic scale and are representative of three independent experiments. In Ca2+-free medium, 45% ± 5% of the 125I-calmodulin dissociated with a half-time (t½) = 474 ± 156 s, and the remainder with a t½ = 143 ± 29 min; the comparable numbers in Ca2+-containing medium were t½ = 180 ± 48 s (44% ± 2%) and 74 ± 9 min.

Figure 2.

Equilibrium binding of 125I-calmodulin to pure InsP3 receptors in the absence and presence of Ca2+. SPA-InsP3 receptor beads were incubated with 125I-calmodulin (3 nM) in the presence of the indicated concentrations of unlabeled calmodulin, first in Ca2+-free medium (•, [Ca2+]m ≈ 2 nM) and then after addition of Ca2+ (○, [Ca2+]m ≈ 30 μM). C denotes the control. Results (means ± SEM) are from three independent experiments.

Although they are structurally unrelated, both calmidazolium (Calbiochem) and W7 (Calbiochem) preferentially bind to Ca2+–calmodulin (28) and thereby attenuate the Ca2+-dependent effects of calmodulin. In the presence of Ca2+ ([Ca2+]m ≈ 30 μM), both calmidazolium (50 μM) and W7 (500 μM) almost abolished binding of 125I-calmodulin to InsP3 receptors: binding was reduced to 13% ± 3% (n = 3) and 8% ± 4% (n = 3) of its control value, respectively. The two compounds had very different effects in the absence of Ca2+; calmidazolium enhanced 125I-calmodulin binding by 240% ± 10% (n = 3), while W7 inhibited it by 49% ± 3% (n = 3). InsP3 (1 μM) only modestly inhibited 125I-calmodulin binding in the absence (22% ± 2%, n = 3) or presence (9% ± 3%, n = 3) of Ca2+, indicating that calmodulin and InsP3 bind to distinct sites on the InsP3 receptor.

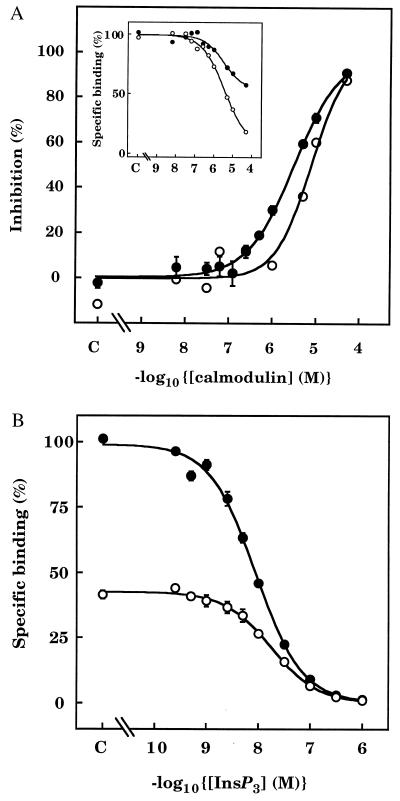

The characteristics of [3H]InsP3 binding to the receptor beads were similar to those reported previously (24): in Ca2+-free medium, [3H]InsP3 bound to a single class of high-affinity sites (Kd = 6.2 ± 0.4 nM, nH = 0.95 ± 0.04, n = 3). In the absence of Ca2+, calmodulin inhibited [3H]InsP3 binding to both purified receptors on SPA beads and cerebellar membranes (Fig. 3A). The effect was not a consequence of calmodulin binding directly to [3H]InsP3, and thereby depleting the medium of free radioligand, because in an equilibrium dialysis assay performed under conditions identical to those of the SPA assays, there was no detectable binding of [3H]InsP3 to calmodulin (not shown). Using SPA to compare [3H]InsP3 binding in the presence of 3 μM calmodulin with that observed after incubating with 10 μM calmodulin and then diluting the medium to reduce the calmodulin concentration to 3 μM, we established that the inhibitory effect of calmodulin reversed within 20 min (Table 1). Previous studies of cerebellar InsP3 receptors failed to detect an effect of calmodulin (2–3 μM) on InsP3 binding (29, 30). The combination of the higher pH used in those experiments, which is known to alter the conformation of calmodulin and inhibit its Ca2+-independent interaction with ryanodine receptors (18), and the high concentration of radioligand used are likely to have contributed to the discrepancy. Indeed, in our experiments increasing the pH to 8.3 had the anticipated stimulatory effect on [3H]InsP3 binding, but abolished the effect of calmodulin (not shown). There are also likely to be genuine differences in the effects of calmodulin between tissues (11, 19, 20): types 1 and 2 InsP3 receptors bind to Ca2+–calmodulin, whereas type 3 receptors appear not to (27).

Figure 3.

Calmodulin inhibits [3H]InsP3 binding to InsP3 receptors. (A) Effects of calmodulin in Ca2+-free medium on equilibrium binding of [3H]InsP3 (3 nM) to cerebellar membranes (○, typical results from one of three independent preparations) or to pure InsP3 receptors on SPA beads (•, means ± SEM of three independent receptor purifications). Results are shown as percentages of the maximal inhibition obtained in the presence of a saturating concentration of calmodulin (derived by extrapolation of the binding curve to infinite calmodulin concentration). (Inset) Typical effects of calmodulin on specific binding of [3H]InsP3 to pure InsP3 receptors from two preparations, showing the differences in the maximal inhibition caused by calmodulin. (B) Equilibrium competition binding curves are shown for specific [3H]InsP3 binding to InsP3 receptors in Ca2+-free medium in the absence of calmodulin (•) and then after addition of a submaximal concentration of calmodulin (3 μM) (○). Results are the means ± SEM of three independent experiments.

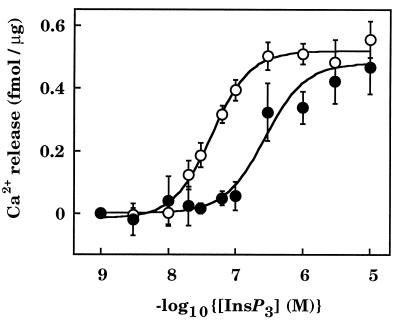

Calmodulin (10 μM) inhibited binding of [3H]InsP3 (1 nM) to cerebellar microsomes by 36% ± 3% (n = 4), and it significantly reduced the 45Ca2+ release evoked by submaximal concentrations of InsP3 without affecting that evoked by maximal concentrations (Fig. 4). These results also confirm that the effects of calmodulin are mediated through a cytosolic site on InsP3 receptors.

Figure 4.

Calmodulin inhibits InsP3-evoked Ca2+ release from cerebellar microsomes. Cerebellar microsomes were loaded with 45Ca2+ in the absence (○) or presence (•) of 10 μM calmodulin before addition of the indicated concentrations of InsP3 in the continued presence or absence of calmodulin. The results (means ± SEM of 3–17 independent experiments, each performed in triplicate) show the amount of Ca2+ released during the 45-s incubation with InsP3.

Although the maximal extent of the inhibition of [3H]InsP3 binding by calmodulin was consistent between experiments using the same receptor preparation, it varied between preparations (Fig. 3A Inset). In four experiments from two separate receptor purifications, the maximal inhibition of [3H]InsP3 binding by calmodulin was 86% ± 3%, while in two experiments from a third purification the inhibition was only 43% and 42%; similar results were obtained with cerebellar membranes (not shown). The concentration range over which calmodulin inhibited InsP3 binding was, however, similar in all preparations analyzed by SPA (IC50 = 3.1 ± 0.2 μM, nH = 0.81 ± 0.04, n = 3) and in cerebellar membranes (IC50 = 7.8 ± 0.3 μM, nH = 1.5 ± 0.7, n = 3) (Fig. 3A). The reasons behind the differences in the maximal effects of calmodulin between receptor preparations and the previously reported effects of storage conditions on calmodulin binding (29) are unclear, although they are not a consequence of calmodulin contamination. From equilibrium competition binding experiments, the Kd for InsP3 was 6.2 ± 0.4 nM (nH = 0.95 ± 0.04; n = 3) in the absence of calmodulin and 15.2 ± 1 nM (nH = 0.97 ± 0.05; n = 3) in the presence of 3 μM calmodulin (Fig. 3B).

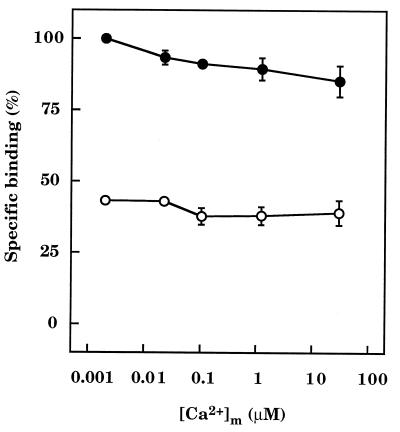

In the absence of calmodulin, increasing [Ca2+]m from ≈2 nM to ≈30 μM caused a small decrease (15% ± 4%, n = 3) in binding of [3H]InsP3 to InsP3 receptors (Fig. 5). The inhibitory effect of a submaximal concentration of calmodulin on [3H]InsP3 binding was not, however, affected by [Ca2+]m. Calmodulin (3 μM) inhibited InsP3 binding by 57% ± 1% (n = 3) when [Ca2+]m was ≈2 nM, by 54% ± 3% (n = 3) when it was ≈30 μM, and by similar amounts at all intermediate [Ca2+]m (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Calmodulin inhibition of [3H]InsP3 binding is independent of Ca2+. Results (means ± SEM of three independent experiments) show the effect of varying [Ca2+]m on the specific binding of [3H]InsP3 (3 nM) to receptor beads in the absence (•) and presence (○) of a submaximal concentration of calmodulin (3 μM).

In the absence of Ca2+ ([Ca2+]m ≈ 2 nM), the inhibition of [3H]InsP3 binding by calmodulin was minimally affected by either W7 or calmidazolium, whereas in the presence of Ca2+, both calmidazolium and W7 reversed the inhibitory effects of calmodulin (Table 2). Neither antagonist affected [3H]InsP3 binding in the absence of calmodulin (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

In peripheral tissues, intracellular concentrations of soluble calmodulin are about 2–6 μM, but both the total and soluble calmodulin concentrations (≈19 μM) are about 4-fold higher in cerebellum (31). Our results therefore suggest that the inhibition of both [3H]InsP3 binding (IC50 = 3.1 μM; Fig. 3) and InsP3-evoked Ca2+ release (Fig. 4) in cerebellum occur at concentrations of calmodulin likely to occur within the cytosol of Purkinje neurons, the cerebellar cells within which most InsP3 receptors (32) and calmodulin (33) are located. Within Purkinje cells, the subcellular distributions of calmodulin and InsP3 receptors are also similar. Both occur at highest density in dendritic spines (32, 34), the sites of glutaminergic innervation by parallel fibers, and each is associated with stacks of smooth endoplasmic reticulum (32, 34). Endogenous calmodulin might therefore provide an explanation for the observation that intact Purkinje cells are, despite their exceptionally high levels of InsP3 receptors, unusually insensitive to InsP3 (35), whereas cerebellar microsomes are similar to other tissues in their InsP3 sensitivity (36) (Fig. 4). Such tonic inhibition of InsP3 receptors is likely to be particularly important in dendritic spines, because within their very small volume (≈5 × 10−17 liters), spontaneous formation of even a few molecules of InsP3 might otherwise cause maximal Ca2+ mobilization.

Estimates of the cytosolic InsP3 concentration of unstimulated cells are almost invariably higher (37, 38), and often much higher (39, 40), than the concentrations required to evoke Ca2+ mobilization from the same cells after permeabilization. The discrepancy has been ascribed to intracellular compartmentalization of InsP3 (38), but it may also reflect the tonic inhibition of InsP3 receptors by a cytosolic component that is lost during permeabilization. Our results suggest that calmodulin may be an endogenous inhibitor of InsP3 receptors. Such tonic inhibition of InsP3 receptors by calmodulin would also be consistent with calmodulin antagonists causing both Ca2+ release and Ca2+ entry in Dictyostelium (41) and with inhibition of InsP3-stimulated Ca2+ release from pancreatic β cells by calmodulin (19).

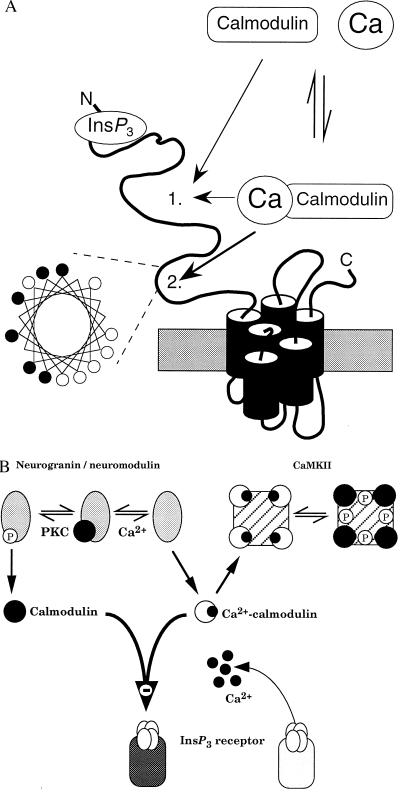

Most interactions between calmodulin and its targets are Ca2+-dependent (1). The only previously demonstrated interaction between calmodulin and InsP3 receptors was also Ca2+-dependent and mediated by a single basic amphipathic helix within the central modulatory domain of the receptor (27) that is similar to those found in other Ca2+–calmodulin-binding proteins (42) (Fig. 6A). The effect of calmodulin on InsP3 binding was, however, entirely insensitive to changes in Ca2+ concentration: the inhibition caused by a submaximal calmodulin concentration was similar over a range of Ca2+ concentration wider than that likely to occur physiologically (Fig. 5). Furthermore, Ca2+–calmodulin antagonists substantially reduced the effects of calmodulin when the Ca2+ concentration was high and were much less effective when the Ca2+ concentration was low, indicating that both calmodulin and Ca2+–calmodulin inhibit InsP3 binding. Our observation that the effects of calmodulin antagonists on InsP3 receptors depend on the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration may have contributed to the conflicting results obtained with such antagonists in previous studies (19, 20, 43).

Figure 6.

Interactions between calmodulin and neuronal InsP3 receptors. (A) Predicted structure of a single subunit of the type 1 InsP3 receptor. Our results establish that both calmodulin and Ca2+–calmodulin bind with the same affinity to a site on the InsP3 receptor to decrease its affinity for InsP3; the exact location of this site 1 is unknown. Another calmodulin-binding site (site 2) within the modulatory domain of the receptor binds only Ca2+–calmodulin (27) and, as the helical wheel representation demonstrates, that site has the basic amphipathic helical structure found in other Ca2+–calmodulin-binding proteins (42). Within the helical wheel, basic residues (Arg, His, Lys) are denoted by •, and hydrophobic residues (Ile, Ala, Trp, Val, Leu) by ○. (B) Both neurogranin (postsynaptic) and neuromodulin (presynaptic) are exclusively neuronal and release their bound calmodulin after either an increase in cytosolic Ca2+ concentration or phosphorylation by protein kinase C (PKC). CaMKII binds Ca2+–calmodulin, which triggers autophosphorylation causing the calmodulin to remain bound after the Ca2+ concentration has returned to its resting level. The ensuing changes in cytosolic calmodulin concentration will regulate binding of InsP3 to its receptor irrespective of the prevailing cytosolic Ca2+ concentration.

Neurons express high levels of several calmodulin-binding proteins with unusual properties. CaMKII is concentrated at postsynaptic sites, notably in hippocampus, and is unusual in that binding of Ca2+–calmodulin causes autophosphorylation, which substantially slows calmodulin dissociation such that calmodulin remains bound after the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration has returned to its resting level (44). Two major calmodulin-binding proteins of brain, neuromodulin (= GAP-43; presynaptic) and neurogranin (postsynaptic), are also unusual in that they preferentially bind Ca2+-free calmodulin and dissociate from it when the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration increases. Both neuromodulin and neurogranin are phosphorylated by protein kinase C, which also causes dissociation of calmodulin (45–47). The presence within neurons of high concentrations of calmodulin, of calmodulin-binding proteins that can either release calmodulin or retain it long after the Ca2+ signal has decayed, and of InsP3 receptors that are inhibited by calmodulin irrespective of the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration has important implications. The changes in cytosolic calmodulin concentration that follow activation of these calmodulin-binding proteins may, according to the complement of proteins expressed, lead to long-lasting increases or decreases in InsP3 receptor sensitivity (Fig. 6B). An increase in cytosolic Ca2+ concentration is essential for induction of many forms of synpatic plasticity (48, 49). A coincident increase in cytosolic Ca2+ concentration and activation of phosphoinositide hydrolysis is essential for induction of long-term depression in cerebellar Purkinje cells (48). Furthermore, the unusual calmodulin-binding proteins, CamKII and neuromodulin, are concentrated in brain areas where synaptic plasticity occurs (44, 46, 47). These observations raise the possibility that transient activation of synaptic inputs may cause substantial redistribution of cytosolic calmodulin with long-lasting consequences for the effectiveness with which InsP3 evokes Ca2+ release (Fig. 6B).

Our results demonstrate that calmodulin binds directly to cerebellar InsP3 receptors; both the multiphasic kinetics of its association and dissociation (Fig. 1) and the shallow equilibrium competition binding curves (Fig. 2) suggest the existence of multiple calmodulin-binding sites on the InsP3 receptor. Ryanodine receptors also express multiple calmodulin-binding sites, some of which bind Ca2+–calmodulin and some of which bind Ca2+-free calmodulin, although estimates of the stoichiometry vary substantially between studies (≤6 per subunit) (18, 50). Such complex binding phenomena, reflecting the likely existence of multiple calmodulin-binding sites as well as the effects of Ca2+ on the conformations of both calmodulin (1) and the InsP3 receptor (51), are not amenable to further analysis without genetic or pharmacological means of distinguishing between the sites. Our preliminary analysis is consistent with the existence of up to 5 calmodulin-binding sites per InsP3 receptor subunit with affinities in both the micromolar and submicromolar range. One of these sites binds only Ca2+–calmodulin (27) and at least one other binds Ca2+–calmodulin and calmodulin with the same affinity (Kd = 3.1 μM) (Fig. 3A); the characteristics of the remaining sites remain to be established (Fig. 6A).

We conclude that calmodulin binds directly to multiple sites on the type 1 InsP3 receptors of cerebellum. One of these sites binds Ca2+–calmodulin (27) and another binds equally well to calmodulin with or without bound Ca2+. The Ca2+-independent site endows InsP3 receptors with an ability to sense the free cytosolic calmodulin concentration whatever the Ca2+ concentration. The presence within neurons, notably those involved in synaptic plasticity, of substantial concentrations of unusual calmodulin-binding proteins that can exert long-lasting effects on the free calmodulin concentration may provide a means whereby synaptic inputs are integrated to control the sensitivity of InsP3 receptors.

Table 1.

Reversible inhibition of [3H]InsP3 binding by calmodulin

| Calmodulin, μM | Inhibition of [3H]InsP3 binding, % |

|---|---|

| 3 | 54 ± 1 |

| 10 | 72 ± 2 |

| 10 then 3 | 49 ± 1 |

SPA methods were used to compare [3H]InsP3 binding to receptors incubated with 3 or 10 μM calmodulin for 40 min. In parallel, receptors were incubated with 10 μM calmodulin (20 min) and then incubated for a further 20 min after dilution to reduce the calmodulin concentration to 3 μM without otherwise changing the composition of the medium. The results (means ± SEM, n = 6) are expressed relative to the specific [3H]InsP3 binding detected in parallel incubations without calmodulin.

Table 2.

Effects of calmodulin antagonists on [3H]InsP3 binding in the presence of calmodulin

| Antagonist | [3H]InsP3 binding, %

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Without Ca2+ | With Ca2+ | |

| Calmidazolium (50 μM) | 13 ± 5 | 43 ± 6 |

| W7 (500 μM) | 24 ± 7 | 76 ± 7 |

In the presence of a submaximal concentration of calmodulin (3 μM), [3H]InsP3 binding was inhibited by 32% ± 1% in the absence of Ca2+ and by 31% ± 2% in its presence. The table shows the extents to which the effects of calmodulin were reversed by preincubation (20 min) with the calmodulin antagonists. Results are means ± SEM of three independent experiments. The inhibitors had no effect in the absence of calmodulin: in Ca2+-free medium, [3H]InsP3 binding was 101% ± 2% and 98% ± 3% of its control value in the presence of calmidazolium and W7, respectively, and in the presence of Ca2+ the comparable numbers were 104% ± 2% and 101% ± 3%.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. A. Patel and S. Matthewson (Amersham International) for the preparation of 125I-calmodulin, Dr. L. Combettes for help with cerebellar microsomes, and Prof. M. J. Berridge for his helpful comments. This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust, the Lister Institute, and the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council.

ABBREVIATIONS

- [Ca2+]m

medium free Ca2+ concentration

- CaMKII

Ca2+–calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II

- InsP3

inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate

- SPA

scintillation proximity assay

Footnotes

SPA technology is covered by U.S. Patent 4568649, European Patent 0154734, and Japanese Patent Application 84/52452.

References

- 1.Gnegy M E. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1993;33:45–70. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.33.040193.000401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carafoli E. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:2115–2118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buratti R, Prestipino G, Menegazzi P, Treves S, Zorzato F. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;213:1082–1090. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu M, Chen T-Y, Ahamed B, Li J, Yau K-W. Science. 1994;266:1348–1354. doi: 10.1126/science.266.5189.1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lan L, Bawden M J, Auld A M, Barritt G J. Biochem J. 1996;316:793–803. doi: 10.1042/bj3160793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dong Y, Kunze D L, Vaca L, Schilling W P. Am J Physiol. 1995;269:C1332–C1339. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.269.5.C1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Phillips A M, Bull A, Kelly L E. Neuron. 1992;8:631–642. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90085-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levitan I B. Annu Rev Physiol. 1994;56:193–212. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.56.030194.001205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taylor C W, Traynor D. J Membr Biol. 1995;145:109–118. doi: 10.1007/BF00237369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen S R W, MacLennan D H. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:22698–22704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee H C, Aarhus R, Graeff R, Gurnack M E, Walseth T F. Nature (London) 1994;370:307–309. doi: 10.1038/370307a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berridge M J. Nature (London) 1993;361:315–325. doi: 10.1038/361315a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chu A, Sumbilla C, Inesi G, Jay S D, Campbell K P. Biochemistry. 1990;29:5899–5905. doi: 10.1021/bi00477a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Witcher D R, Kovacs R J, Schulman H, Cefali D C, Jones L R. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:11144–11152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferris C D, Huganir R L, Bredt D S, Cameron A M, Snyder S H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:2232–2235. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.6.2232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang J, Best P M. Nature (London) 1992;359:739–741. doi: 10.1038/359739a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cameron A M, Steiner J P, Roskams A J, Ali A M, Ronnett G V, Snyder S H. Cell. 1995;83:463–472. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90124-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tripathy A, Xu L, Mann G, Meissner G. Biophys J. 1995;69:106–119. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)79880-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wolf B A, Colca J R, McDaniel M L. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1986;141:418–425. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(86)80189-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hill T D, Campos-Gonzalez R, Kindman H, Boynton A L. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:16479–16484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Richardson A, Taylor C W. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:11528–11533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bosworth N, Towers P. Nature (London) 1989;341:167–168. doi: 10.1038/341167a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Michikawa T, Hamanaka H, Otsu H, Yamamoto A, Miyawaki A, Furuichi T, Tashiro Y, Mikoshiba K. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:9184–9189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patel S, Harris A, O’Beirne G, Cook N D, Taylor C W. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;221:821–825. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patel S, Taylor C W. Biochem J. 1995;312:789–794. doi: 10.1042/bj3120789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stauderman K A, Harris G D, Lovenberg W. Biochem J. 1988;255:677–683. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamada M, Miyawaki A, Saito K, Yamamoto-Hino M, Ryo Y, Furuichi T, Mikoshiba K. Biochem J. 1995;308:83–88. doi: 10.1042/bj3080083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hidaka H, Yamaki T, Naka M, Tanaka T, Hayashi H, Kobayashi R. Mol Pharmacol. 1980;17:66–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maeda N, Kawasaki T, Nakade S, Yokota N, Taguchi T, Kasai M, Mikoshiba K. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:1109–1116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Supattapone S, Worley P F, Baraban J M, Snyder S H. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:1530–1534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kakiuchi S, Yasuda S, Yamazaki R, Teshima Y, Kanda K, Kakiuchi R, Sobue K. J Biochem. 1982;92:1041–1048. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a134019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Satoh T, Ross C A, Villa A, Supattapone S, Pozzan T, Snyder S H, Meldolesi J. J Cell Biol. 1990;111:615–624. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.2.615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin C-T, Dedman J R, Brinkley B R, Means A R. J Cell Biol. 1980;85:473–480. doi: 10.1083/jcb.85.2.473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Means A R, Dedman J R. Nature (London) 1980;285:73–77. doi: 10.1038/285073a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khodakhah K, Ogden D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:4976–4980. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.11.4976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Supattapone S, Danoff S K, Theibert A, Joseph S K, Steiner J, Snyder S H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:8747–8750. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.22.8747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pittet D, Schlegel W, Lew D P, Monod A, Mayr G W. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:18489–18493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhao H, Khademazad M, Muallem S. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:14822–14827. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Horstman D A, Takemura H, Putney J W., Jr J Biol Chem. 1988;263:15297–15303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Challiss R A J, Chilvers E R, Willcocks A L, Nahorski S R. Biochem J. 1990;265:421–427. doi: 10.1042/bj2650421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schlatterer C, Schaloske R. Biochem J. 1996;313:661–667. doi: 10.1042/bj3130661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O’Neil K T, DeGrado W F. Trends Biochem Sci. 1990;15:59–64. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(90)90177-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Palade P, Dettbarn C, Alderson B, Volpe P. Mol Pharmacol. 1989;36:673–680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hanson P I, Schulman H. Annu Rev Biochem. 1992;61:559–601. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.61.070192.003015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baudier J, Deloulme J C, Dorsselaer A V, Black D, Matthes H W D. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:229–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu Y, Storm D. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1990;11:107–111. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(90)90195-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Benowitz L I, Routtenberg A. Trends Neurosci. 1997;20:84–91. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)10072-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Linden D J. Neuron. 1994;12:457–472. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90205-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bliss T V P, Collingridge G L. Nature (London) 1993;361:31–39. doi: 10.1038/361031a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang H-C, Reedy M M, Burke C L, Strasburg G M. Biochemistry. 1994;33:518–525. doi: 10.1021/bi00168a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Marshall I C B, Taylor C W. Biochem J. 1994;301:591–598. doi: 10.1042/bj3010591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]