Abstract

This study addresses the extent of divergence in the ascending somatosensory pathways of primates. Divergence of inputs from a particular body part at each successive synaptic step in these pathways results in a potential magnification of the representation of that body part in the somatosensory cortex, so that the representation can be expanded when peripheral input from other parts is lost, as in nerve lesions or amputations. Lesions of increasing size were placed in the representation of a finger in the ventral posterior thalamic nucleus (VPL) of macaque monkeys. After a survival period of 1–5 weeks, area 3b of the somatosensory cortex ipsilateral to the lesion was mapped physiologically, and the extent of the representation of the affected and adjacent fingers was determined. Lesions affecting less than 30% of the thalamic VPL nucleus were without effect upon the cortical representation of the finger whose thalamic representation was at the center of the lesion. Lesions affecting about 35% of the VPL nucleus resulted in a shrinkage of the cortical representation of the finger whose thalamic representation was lesioned, with concomitant expansion of the representations of adjacent fingers. Beyond 35–40%, the whole cortical representation of the hand became silent. These results suggest that divergence of brainstem and thalamocortical projections, although normally not expressed, are sufficiently great to maintain a representation after a major loss of inputs from the periphery. This is likely to be one mechanism of representational plasticity in the cerebral cortex.

Keywords: plasticity, divergence, cortical magnification

Plasticity of the body map in somatosensory cortex permits the representation of a body part to expand or contract under the influence of enhanced or reduced input from sensory receptors of skin, muscle, and joints and probably underlies perceptual adaptations that occur during learning of new tactile skills (1) and after nerve injury (2) or amputation (3).

Activity-dependent expansion of part of the body map in the cerebral cortex at the expense of adjacent parts may depend upon functional expression of divergent but previously suppressed inputs from the periphery (4, 5) that reach the cortex via the ventral posterior nucleus of the thalamus, upon long-range intracortical connections (6), and/or upon sprouting of axons (5) in one or both pathways.

The extent of thalamocortical divergence is a limiting factor in the potential for expansion of one representation at the expense of another (7–10). It can be magnified by similar divergence of primary afferents to the dorsal column nuclei and of dorsal column nuclear efferents to the ventral posterior thalamic nucleus. The degree of this magnification has been determined in the present study: the representation of the hand was mapped physiologically in the somatosensory cortex of monkeys after making destructive lesions of increasing size in parts of the thalamic representation of the hand. The results show that substantial parts of the thalamic representation of a finger can be removed before the representation of that finger begins to shrink in the cortical somatotopic map. The degree of divergence implied by these results is sufficiently great to explain most cases of representational plasticity in the somatosensory cortex even after substantial peripheral lesions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fifteen macaque monkeys (Macaca mulatta and Macaca nemestrina) were anesthetized with intramuscular ketamine and maintained on a continuous intravenous infusion of Nembutal. In 10, microelectrodes were introduced into one thalamus horizontally from behind, entering the thalamus via the visual cortex and midbrain. The ventral posterior lateral nucleus (VPL) was identified, and receptive field mapping of single units and multiunit clusters responding to natural cutaneous stimulation was used to isolate the extent of the representation of a single finger (which normally occupies a more or less parasagittal lamella, running on a curved trajectory through the anteroposterior extent of VPL; Fig. 1A). Either a small electrolytic lesion was made along the length of a large part of this trajectory by passing 5–8 mA through the electrode as it was withdrawn or the recording electrode was replaced by a dual recording/injection cannula attached to a hydraulic delivery system and 300 nl of 2 or 10 mM kainic acid (pH 3.5) was injected along the trajectory representing a finger. Larger lesions were made by reintroducing the electrode or cannula and making further electrolytic lesions or injections along trajectories dorsal, ventral, medial, and/or lateral and parallel to the first.

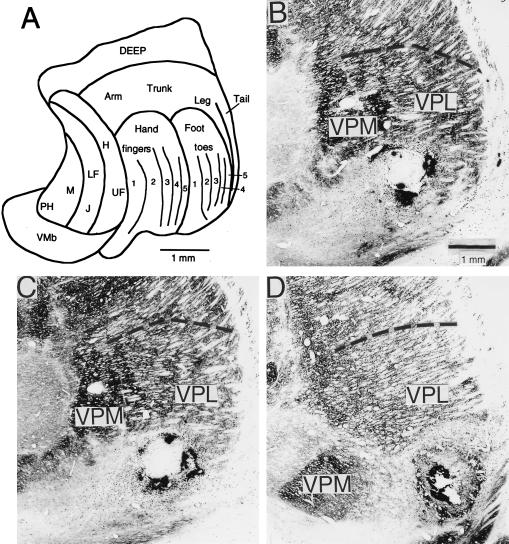

Figure 1.

(A) Representation of the body surface in the normal macaque monkey at a single coronal level of the ventral posterior nucleus (redrawn from ref. 11). The representation of a finger runs in a curved lamella through the full anteroposterior extent of the VPL nucleus. (B–D) Lesions of various sizes in cytochrome oxidase-stained sections from different monkeys. The lesions were made electrolytically along the length of the trajectory representing a finger. All lesions resulted in a reduction of immunostaining for the calcium binding protein parvalbumin (25) in a localized part of the layer IV plexus in area 3b (see Fig. 3C), its size proportional to the size of the thalamic lesion, indicating a loss of thalamocortical fibers.

The monkeys were allowed to recover; 1–5 weeks after lesioning, they were reanesthetized; and the representation of the upper limb was mapped in area 3b of the somatosensory cortex ipsilateral to the lesion, by using the same single and multiunit recording of responses to peripheral stimulation as for the thalamus. Microelectrodes were introduced at 200- to 500-μm intervals and were advanced down the posterior bank of the central sulcus. Five normal monkeys in which the same area was mapped served as controls. At the conclusion of the cortical mapping, the animals were perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), the brains removed, infiltrated with sucrose, and frozen in dry ice. Serial frozen sections 30-μm thick were cut from the thalamus in the frontal plane and from the cortex in the parasagittal plane. Alternate sections were stained with thionin, histochemically for cytochrome oxidase, or immunocytochemically for the calcium binding protein parvalbumin.

Camera-lucida drawings were made of the Nissl- and cytochrome oxidase-stained sections through the thalamus, showing the extent of the lesion and its relationship to the borders of VPL; the volume of VPL occupied by the lesion was calculated. Nissl-stained sections of the cortex were used to locate microelectrode tracks in relation to the cytoarchitecture of area 3b of the somatosensory cortex, and a map of the hand and adjacent parts of the upper limb representation was generated on the flattened cortex, by relating electrode tracks to receptive field data collected during the terminal experiment. The sections stained immunocytochemically for parvalbumin were used to identify regions of area 3b in which the layer IV plexus of parvalbumin-stained thalamocortical fibers was deficient.

RESULTS

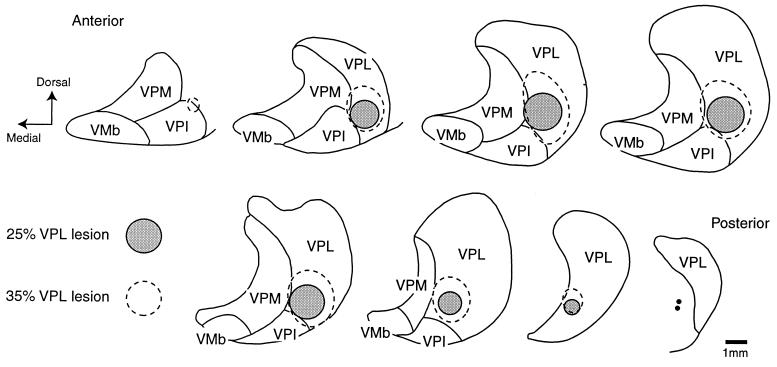

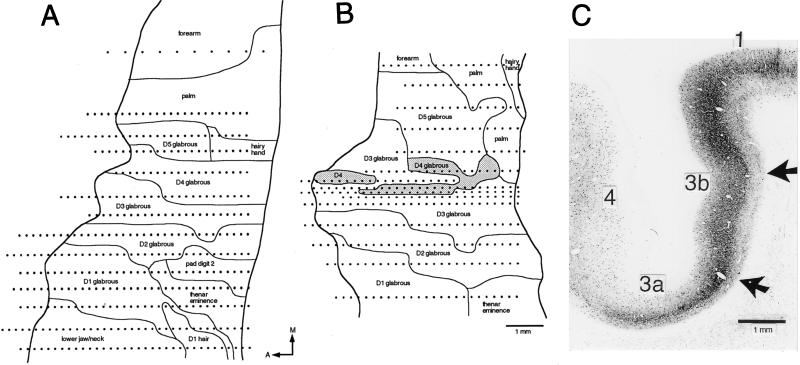

Electrolytic or kainic acid lesions resulted in the destruction of thalamic cells over a region whose size was related to the amount of current passed or volume of excitotoxin injected. The lesioned area was distinguishable by loss of Nissl or cytochrome oxidase staining in the histological sections through the thalamus (Fig. 1). One monkey had a lesion affecting 0.25–5% of VPL, five had lesions affecting 5–10%, four had lesions affecting 10–25%, two had lesions affecting 30–40%, and two had lesions affecting 40% or more of VPL (Fig. 2). The representation of the first (D1) and second (D2) fingers in VPL each occupy 7–10% of its volume; that of the other fingers occupies somewhat less (11). The curving nature of the representations makes it impossible for any small lesions made in the present manner to occupy the representation of one finger throughout its full antero-posterior extent. All lesions resulted in a reduction of immunostaining for parvalbumin in a localized part of the layer IV plexus in area 3b (Fig. 3C), its size proportional to the size of the thalamic lesion, indicating a loss of thalamocortical fibers.

Figure 2.

Camera-lucida drawings of frontal sections in anteroposterior order through the ventral posterior nuclei of one monkey, upon which have been plotted the extents of the lesions in VPL of two different brains. The cortical maps from these cases are illustrated in Fig. 3. VMb, basal ventral medial nucleus; VPI, ventral posterior inferior nucleus.

Figure 3.

Representation of the upper limb in area 3b of the ipsilateral somatosensory cortex after lesioning the thalamic representation of a finger. (A) Map for which less than 30% of VPL was destroyed, the lesion being centered on the thalamic representation of the fourth finger (D4); this and lesions of similar size were without effect on the size of the cortical map of the finger whose thalamic representation was at the heart of the lesion. (B) Cases such as this, in which approximately 35% of the volume of VPL was destroyed, revealed a shrunken fragmented cortical representation of the finger (D4) and expansion of the representations of neighboring fingers (D3 and D5). Dots represent sites of microelectrode penetrations. (C) Localized reduction in parvalbumin staining (25) (arrows) in the layer IV plexus of area 3b, indicating destruction of thalamocortical fibers resulting from a lesion in VPL.

Small cylindrical lesions 0.5–1 mm in diameter that ran anteroposteriorly through the thalamus affecting over much of their length part of the representation of a single finger (11) were without effect on the cortical map in area 3b (Fig. 3A). In these cases, a complete cortical representation of the finger was found, its internal topography was intact, and the size of the representation (2.5–10 mm2) was similar to that found in the control monkeys (see also ref. 12). Receptive fields of neurons within the finger representation were identical in size to those in normal monkeys and their responsiveness to stimuli was indistinguishable from those of normal monkeys within the limitations of the experimental setup.

Lesions centered in the representation of a single finger were without effect upon the cortical representation of that finger until approximately 30% of the volume of VPL was destroyed (Figs. 2 and 3B). When 30–35% of VPL was lesioned, the cortical representation of the finger whose thalamic representation was at the center of the lesion was reduced in size (Fig. 3B). In the case illustrated, involving a 35% loss of VPL and after a survival of 2 weeks, the cortical representation of the fourth finger was much narrower than in controls, was split by the representation of the middle finger, and was 59% less extensive in area than in normal monkeys (1.5 mm2 vs. 3.7 ± 0.71 mm2). The receptive fields of many neurons in the diminished area 3b representation were indistinguishable in size from those of controls and had equally well-defined borders. All parts of the finger appeared to be represented in the shrunken broken finger representation. The reduction of the cortical representation of the finger was accompanied by expansions of the representations of adjacent fingers. In the case illustrated in Fig. 3, the representations of the third and fifth fingers expanded to 8.3 mm2 and 4.5 mm2 in comparison with means (±SEM) of 4.3 ± 0.78 mm2 and 3.2 ± 0.64 mm2, respectively, in the five controls.

After lesions that destroyed 35–40% of VPL, and likely affected the whole thalamic hand representation, the cortical representation of most of the hand failed. In the region of area 3b normally devoted to the representation of the hand, neurons in layer IV were uncharacteristically silent and failed to respond even to intense peripheral stimuli, and a topographic map of the upper limb could not be defined. No neurons in the area of reduced activity responded to stimulation of the trunk or face.

Behaviorally, monkeys with even the smallest lesions of VPL displayed evidence of some reduction in tactile acuity in the affected digit, failing to withdraw the hand when the digit was stimulated while their attention was distracted. Larger lesions gave evidence of a loss of tactile sensation in the palm and in two or more digits, and the largest lesions suggested the presence of complete anesthesia of most of the upper limb.

DISCUSSION

The present results imply that despite removal of large parts of the representation of a finger in the thalamus, remaining thalamocortical connections are capable of maintaining a cortical representation of that finger, which after a certain limit diminishes in size. After a second limit is reached, the whole representation breaks down. Maintenance of a cortical finger representation in the face of reducing thalamic inputs is likely to depend upon: (i) preservation of part of the thalamic finger representation, reflecting the extended nature of its thalamic representation and the divergence of its cortical projection; and (ii) divergence of peripheral inputs from the finger to the dorsal column nuclei and of the outputs of these nuclei to the thalamus. In this way, inputs from a specific finger would reach thalamic cells that represent adjacent fingers. Although normally suppressed in the production of the fine grain somatotopic map in the cerebral cortex, as determined physiologically, under the conditions of these experiments they would be exposed and thus maintain a cortical map.

The results may be compared with those in the Silver Spring monkeys (5) in which a 12-year deafferentation of the upper limb resulted in transneuronal degeneration of cells in the cuneate nucleus and in the forelimb representation in VPL (13), removing a volume of cells approximately equal to that of the larger lesions in the present study. In these animals, the cortical upper limb representation, which should have been silenced by such a procedure, showed encroachment of an expanded representation of the lower jaw (5). This could depend in large part on amplified divergence of the type demonstrated herein.

The extent of divergence in the thalamocortical projections of VPL and ventral posterior medial thalamic nucleus (VPM) was demonstrated in a previous study (8). It was shown the adjacent cells within the same part of the thalamic representation of a part of the body, such as a finger, can project to foci in area 3b up to 1.5 mm apart, but no more. Most cells in the thalamic representation send their axons to a common zone in area 3b that constitutes the cortical representation of that finger. The 1.5-mm divergence, however, ensures that the axons of a few cells actually terminate in the representation of an adjacent finger. The 1.5-mm divergence can account for the “cortical distance factor” (9), the 1- to 1.5-mm expansion of a part of the cortical representation at the expense of adjacent parts that occurs in the short-term after amputation of a digit or division of a single peripheral nerve (2, 14). It cannot account for expansions greater than 1–5 mm, which occur after sectioning of multiple nerves (10) or after even more extensive deafferentations (5, 15). For this, other mechanisms have been invoked. Among the proposed mechanisms, the normal divergence of inputs that occurs at each successive relay center in the ascending dorsal column-lemniscal pathway (i.e., in the dorsal column nuclei and thalamus) holds some appeal, since a relatively small degree of divergence of primary afferent inputs to the dorsal column nuclei or principal trigeminal nucleus could be “magnified” by additional divergence of lemniscal fibers at the ventral posterior nucleus and of its projections to area 3b. This would result in the amplification of thalamocortical divergence beyond the 1.5-mm set by the divergence of individual thalamocortical neurons.

The present study tested the limits of this amplified divergence by placing lesions at the point at which subcortical divergence would be maximal, i.e., in the thalamus itself. The results are surprising in the extent to which the cortical representation of a finger could be maintained after extensive destruction of thalamic neurons. After the smallest lesions, the preservation of the cortical finger representation can probably be explained by overlap and divergence of projections from remaining parts of the thalamic finger representation: the curving trajectory of the thalamic representation as it extends anteroposteriorly through VPL, and its dorso-ventral extent (11), makes it impossible for the orthogonally oriented electrodes to have destroyed more than a small part of it. It is inconceivable, however, that the largest lesions did not remove all or most of the thalamic representation of the target finger. Under these circumstances, the cortical representation of the same finger held up to some extent but was encroached upon by that of neighboring fingers. We take this observation to indicate the diverging projections of relay cells in the still unremoved parts of the thalamic representations of the neighboring fingers. Beyond a critical point, approaching a 40% volume loss of VPL, the cortical representation of the whole hand fell silent. At this point, it is assumed, the whole representation of the hand in the thalamus had been removed.

The premise upon which the above interpretation is based is that, under normal conditions, the divergent projections are weaker or suppressed, probably by GABAergic inhibitory mechanisms (16), only being revealed under activity-dependent conditions. That is, when their activity is enhanced by increased or coherent sensory input (1, 17) from the part that they represent, the representation of the part that they overlap being suppressed, or when inputs to the overlapped part of the representation are reduced, as in peripheral nerve section (2, 4, 9, 15), amputation (14, 15, 18, 19), or suppression of activity (20).

At the 1- to 5-week survival times used, the silenced cortical hand representation was not encroached upon by the adjoining representations of the face. This contrasts with the Silver Spring monkeys in which the lower jaw representation, in particular, had invaded cortical territory formerly occupied by the representation of the hand (5). In terms of the divergence hypothesis, presented above, the failure of expansion of the face representation in the present cases of larger electrolytic lesions may have stemmed from destruction of fibers of passage from VPM as they traversed the lesion in VPL. This explanation would not apply, however, in the case of the kainic acid lesions.

It is possible that there is little or no overlap of trigeminal and dorsal column inputs to the thalamus across the VPM/VPL border, thus preventing expansion of the face representation on the basis of ascending divergence, but this has not been explored in detail. There is overlap in the peripheral distributions of the mandibular nerve and upper two cervical nerves in monkeys (21), and this is reflected in overlap of the representations of the lower jaw and neck in area 3b (22). The degree of divergence in the cortical projections of VPM and VPL, coupled with a lack of divergence in the subcortical inputs to these two nuclei, in these short-term experiments, could militate against an expansion of the face representation into that of the hand. Long-range intracortical connections do not extend across the border of the hand and face representations to a significant extent (22) and so could not provide a basis for short-term expansion of the face representation. In the long-term, therefore, as in the Silver Spring monkeys, other mechanisms such as sprouting of intracortical connections (23) may need to be invoked to explain the expansion of the face representation. Axon sprouting at subcortical centers (15) may also have been involved.

The present results also imply that the spinothalamic system is incapable of supporting a hand representation in the absence of the thalamic relay for lemniscal fibers. Although some of the terminations of the anterolateral system were inevitably destroyed by the lesions, substantial numbers end outside VPL in adjacent nuclei such as the posterior and in the small-celled zones of calbindin immunoreactive cells around VPM (24), and their cortical projections would have been spared.

The behavioral observations in the lesioned monkeys, although not quantitatively evaluated, suggest that the presence of a complete map, as demonstrated with conventional mapping procedures, can still be accompanied by perturbed sensory perception, an effect that is, in fact, commonly associated with amputations and peripheral nerve injuries. The maintenance of a map cannot, therefore, be equated with the maintenance of normal function.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grant NS-21377 from the National Institutes of Health.

ABBREVIATIONS

- VPL

ventral posterior lateral thalamic nucleus

- VPM

ventral posterior medial thalamic nucleus

References

- 1.Recanzone G H, Merzenich M M, Jenkins W M, Grajski K A, Dinse H R. J Neurophysiol. 1992;67:1031–1056. doi: 10.1152/jn.1992.67.5.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Merzenich M M, Kaas J H, Wall J T, Sur M, Nelson R J, Felleman D J. Neuroscience. 1983;10:639–666. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(83)90208-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramachandran V S, Rogers-Ramachandran D, Stewart M, Pons T P. Science. 1992;258:1159–1160. doi: 10.1126/science.1439826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaas J H. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1991;14:137–168. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.14.030191.001033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pons T P, Garraghty P E, Ommaya A K, Kaas J H, Taub E, Mishkin M. Science. 1991;252:1857–1860. doi: 10.1126/science.1843843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lund J P, Sun G-D, Lamarre Y. Science. 1994;265:546–48. doi: 10.1126/science.8036500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garraghty P E, Sur M. J Comp Neurol. 1990;294:583–593. doi: 10.1002/cne.902940406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rausell E, Jones E G. J Neurosci. 1995;15:4270–4288. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-06-04270.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaas J H, Merzenich M M, Killackey H P. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1983;6:325–356. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.06.030183.001545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garraghty P E, Hanes D P, Florence S L, Kaas J H. Somatosens Mot Res. 1994;11:109–117. doi: 10.3109/08990229409028864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones E G, Friedman D P. J Neurophysiol. 1982;48:521–544. doi: 10.1152/jn.1982.48.2.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaas J H, Pons T P, Wall J T, Garraghty P E, Cusick C G. Somatosens Res. 1987;4:309–331. doi: 10.3109/07367228709144612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rausell E, Cusick C G, Taub E, Jones E G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:2571–2575. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.7.2571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garraghty P E, Kaas J H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:6976–6980. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.16.6976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Florence S L, Kaas J H. J Neurosci. 1995;15:8083–8095. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-12-08083.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Merzenich M M, Nelson R J, Stryker M P, Cynader M S, Schoppmann A, Zook J M. J Comp Neurol. 1984;224:591–605. doi: 10.1002/cne.902240408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones E G. Cereb Cortex. 1993;3:361–372. doi: 10.1093/cercor/3.5.361-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clark S A, Allard T, Jenkins W M, Merzenich M M. Nature (London) 1988;332:444–445. doi: 10.1038/332444a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Manger P R, Woods T M, Jones E G. Proc R Soc London Ser B. 1996;263:933–939. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1996.0138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Calford M B, Tweedale R. Nature (London) 1988;332:446–448. doi: 10.1038/332446a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sherrington C S. In: Selected Writings of Sir Charles Sherrington. Denny-Brown D, editor. London: Hamish Hamilton Medical Books; 1939. pp. 31–93. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manger, P. R., Woods, T. M., Muñoz, A. & Jones, E. G. (1997) J. Neurosci., in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Darian-Smith C, Gilbert C D. Nature (London) 1994;368:737–740. doi: 10.1038/368737a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rausell E, Bae C S, Viñuela A, Huntley G W, Jones E G. J Neurosci. 1992;12:4088–4111. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-10-04088.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones E G, Hendry S H C. Eur J Neurosci. 1989;1:222–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1989.tb00791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]