Abstract

By using a simplified model of small open liquid-like clusters with surface effects, in the gas phase, it is shown how the statistical thermodynamics of small systems can be extended to include metastable supersaturated gaseous states not too far from the gas–liquid equilibrium transition point. To accomplish this, one has to distinguish between mathematical divergence and physical convergence of the open-system partition function.

Keywords: gas phase/spherical clusters/surface effects/open partition function/physical convergence

Small-system thermodynamics (1) is a branch of equilibrium thermodynamics. Metastable states are not, strictly speaking, equilibrium states. However, it is shown in this paper, by means of a single, simple example, that metastable states of open systems can be included in small-system statistical thermodynamics if physically appropriate modifications of the mathematical analysis are made.

First we present a very brief digression on statistical mechanical partition functions (2). The conventional partition functions for a one-component macroscopic system are all functions of three independent thermodynamic variables, at least one of which is an extensive variable, for example N (number of molecules), V (volume), or E (energy). Thus the “size” of the macroscopic system is specified. In addition, there is an unconventional partition function, Υ (μ, p, T), a function of μ (chemical potential), p (pressure), and T (temperature), all intensive variables. This partition function is usually referred to as “generalized” or “completely open.” This is a troublesome partition function in macroscopic statistical mechanics that requires special treatment (2). The primary problems are that only two of μ, p, and T can be independent, and the size of the system is not specified. However, in the thermodynamics of small or finite systems (not macroscopic) μ, p, and T can all be independent in a completely open system. In fact, these intensive variables determine the size of the small system (1). Incidentally, the way to avoid the above-mentioned difficulties with a completely open macroscopic system is to: formulate the corresponding small-system Υ (μ, p, T); deduce the small-system thermodynamic properties from Υ; and then find the macroscopic limits of these properties as μ, p, and T approach their macroscopic relationship (1).

In the present paper, p is an unimportant variable (incompressibility is assumed), so that Υ is a function of μ and T only.

We consider, below, spherical liquid-like droplets or clusters in a supersaturated gas phase metastable with respect to the liquid phase. We shall be concerned not with the kinetics and mechanism of homogeneous nucleation of the liquid state from the vapor (3–7), but rather with the converse problem: metastable vapor states that can persist more or less indefinitely.

Other statistical mechanical treatments, not related to the thermodynamics of small systems, have been carried out by several authors (8–11). However, the small-system approach used here, based on the completely open partition function Υ (1), seems to have the advantages of transparency and simplicity. Also, limitation of the range of metastability arises in a natural way.

The previous work of Langer (12) deserves special mention. Using a simple cluster model for a first-order phase transition in a ferromagnet, Langer encountered some of the basic features to be presented here. The present work differs, however, in several respects: the formalism here is based throughout on the thermodynamics of small systems and the current problem is intended to illustrate the possible extension of open small-system thermodynamics to metastable states; the small liquid clusters in the present paper are allowed free rotation and translation (absent, of course, in the ferromagnet model), with significant consequences; and a certain series expansion of the partition function Υ is introduced as an alternative mathematical approach.

Metastable clusters have been found to occur in many physically realizable systems, including supersaturated vapors (13) and phase transformations in solid solutions (14). Metastable droplets may also play a role in the dynamical clusters that have been shown to exist in supercooled liquids (15–20).

The Model

The notation and simplified model used here are taken from Hill (ref. 1, Part I, p. 71, and Part II, pp. 83–87): the small system is a spherical, incompressible liquid aggregate or cluster, in the gas phase. The canonical ensemble partition function for a single cluster of N molecules at temperature T is

|

1 |

where c(T) is a collection of constants, cN4 arises from rotation and translation (ref. 1, Eq. 3–62), the term in α is a surface contribution (α is positive and proportional to the surface tension) and j(T) is the macroscopic liquid partition function per molecule (ref. 1, Eq. 10–53). The macroscopic liquid chemical potential is μ0 = −kT ln j (a small pressure dependence of the liquid μ appears in Fig. 1, but is ignored here). For an open system (i.e., cluster) in the gas phase, N is free to fluctuate at given μ and T as the cluster gains or loses molecules. The corresponding completely open partition function is

|

2 |

Because important values of N are rather large, as a further simplification we replace the sum in Eq. 2 by an integral:

|

3 |

where δ = (μ0 − μ)/kT. The probability that a cluster contains between N and N + dN molecules is then (1)

|

4 |

and the mean size of a cluster is (1)

|

5 |

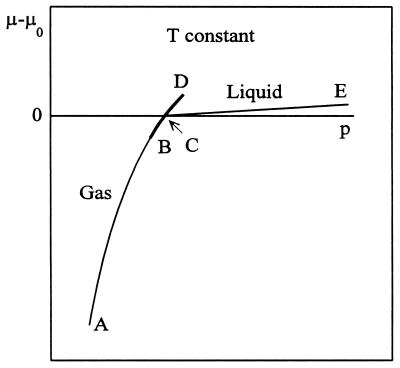

Figure 1.

Schematic plot of the chemical potential of gas and liquid as functions of pressure p at constant temperature T. Clusters of significant size in the gas phase are possible only in the region BCD (heavy line). The metastable (supersaturated) region of interest here is CD.

Stable and Metastable States

For orientation, conventional macroscopic systems (gas, liquid) are represented schematically in Fig. 1 in the form of a plot of μ − μ0 as a function of pressure p at constant T. The phase transition occurs at C, where μ = μ0 and the two chemical potential curves cross. The overall stable or equilibrium path (lower μ) is ACE. At C, the clusters referred to above are in the saturated vapor phase that is in equilibrium with bulk liquid. Here, δ = 0. To have sizeable clusters, the temperature would need to be near the critical temperature where the surface tension is small (1). Significant but smaller clusters would be present in the gas phase along the darkened stable path BC, where δ is small and positive. Correspondingly, if the phase transition at C can be avoided (not nucleated), the gas phase, with larger clusters and now supersaturated, will persist along the metastable path CD, where δ is small and negative. If a switch to the liquid path CE does not occur, there is no point of physical discontinuity along the path BD. Thus it should be possible to apply small-system thermodynamics to the metastable states along CD as well as to stable states on BC. This possibility is illustrated in the discussion below, by using the above model.

Mathematical and Physical Convergence

When δ = 0 (i.e., μ = μ0), the integrand in Eq. 3 rises to a maximum and then falls to zero as N increases; the integral converges. When δ is small and positive (stable states), at larger N the integrand falls to zero even faster and the integral converges. However, when δ is small and negative, after a maximum the integrand decreases to a minimum, but then eventually rises rapidly to infinity: the integral diverges mathematically. However, physically, the situation is more complicated.

To simplify Eq. 3, we introduce the scale changes n = α3/2N and ɛ = α−3/2δ. Then

|

6 |

Typically, α might be of order of 0.4 [α = 0.4 gives  = 85.2 from

= 85.2 from  = 21.5 (a factor of about 4) at ɛ = 0, or μ = μ0, by using Eq. 18 below]. Thus n would be smaller than N and ɛ larger than δ.

= 21.5 (a factor of about 4) at ɛ = 0, or μ = μ0, by using Eq. 18 below]. Thus n would be smaller than N and ɛ larger than δ.

If we denote the integral in Eq. 6 by Υ′, then the probability that a cluster has n between n and n + dn is

|

7 |

as in Eq. 4.

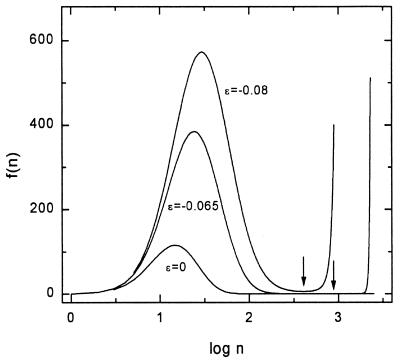

Let f(n) represent the integrand in Eq. 6 [thus f(n) is proportional to P′(n)]. In Fig. 2, f(n) is plotted against log n for ɛ = 0, −0.065, and −0.08. In the ɛ = −0.065 case, f(n) practically vanishes over a long range in n but eventually rises suddenly toward f = ∞. Physically, this means that there are almost no clusters of sizes between about n = 200 and n = 1,900 (this effect is even more extreme for smaller values of −ɛ). As the gas pressure is raised from point C (ɛ = 0) in Fig. 1 to reach the case ɛ = −0.065, gas molecules will aggregate further to produce the bell-shaped equilibrium curve for ɛ = −0.065 in Fig. 2. However, the sudden rise in f(n) beginning around n = 2,000 will not be included in an equilibrium distribution, reached in this way, in a realistic (finite) time period. This follows because the almost absent clusters of sizes n = 200 to n = 1,900 introduce an extreme kinetic barrier or bottleneck to the growth of clusters larger than n = 1,900.

Figure 2.

Plot of the integrand f(n) in Eq. 6 as a function of log n for ɛ = 0, −0.065, and −0.08. The two vertical arrows locate the minima in f(n).

To summarize: the bell-shaped curve in the ɛ = −0.065 case represents the metastable state; the “sudden rise” (above), if it should be reached kinetically, would signify the loss of the metastable state (supersaturated gas) to become bulk liquid.

The mathematical consequence, for the metastable state, of the effective kinetic inaccessibility of the “sudden rise” is that the upper limit ∞ in the Υ′ integral for ɛ = −0.065 should be replaced by a finite limit (see below). This “physically” modified Υ′ integral will not diverge.

In the ɛ = −0.08 case (Fig. 2), the minimum in the f(n) curve establishes a modest bottleneck. However, this case no doubt represents a metastable state that would not survive long enough to study experimentally because of “leakage” through the bottleneck to higher n values. The rapid increase in f(n) beyond the bottleneck would correspond physically to formation of bulk liquid (the system falling from just above D to the CE curve in Fig. 1). Curves of the sort in Fig. 2 can serve as the basis for a theoretical kinetic study of lifetimes of metastable states, somewhat related to refs. 3–7; see especially Langer (21).

To locate the maximum and minimum in f(n) when ɛ is negative, we use d ln f/dn = 0. This leads to

|

8 |

a cubic equation in n1/3. The two positive roots (for suitable values of −ɛ) give n0, the value of n at the minimum in f(n), and n1, the value at the maximum. Table 1 presents values of n0, n1, and the corresponding values of f(n), denoted f0 and f1. The ratio f1/f0, from this table, suggests that long-lived metastable states for this model might be expected for −ɛ ≤ 0.07 or 0.075.

Table 1.

Properties of the extrema in the integrand in Eq. 6

| −ɛ | n1 | f1 | n0 | f0 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 14.70 | 115.6 | – | – |

| 0.03 | 17.72 | 187.4 | 10,568.9 | 4.37 × 10−56 |

| 0.04 | 19.10 | 225.3 | 4,322.6 | 2.46 × 10−26 |

| 0.05 | 20.78 | 274.9 | 2,121.2 | 4.68 × 10−13 |

| 0.06 | 22.88 | 341.9 | 1,160.0 | 3.45 × 10−6 |

| 0.065 | 24.15 | 384.5 | 881.1 | 5.47 × 10−4 |

| 0.07 | 25.61 | 435.4 | 677.5 | 2.625 × 10−2 |

| 0.08 | 29.42 | 572.6 | 409.6 | 5.340 |

| 0.10 | 47.77 | 1,184.4 | 138.2 | 901.8 |

The two vertical arrows in Fig. 2 indicate the location of log n0, the minimum in f. The flat, almost zero, range (“bottleneck”) in f around the minimum in the ɛ = −0.065 case becomes even more extensive as −ɛ decreases.

The approximate value of n where f(n) begins its sudden rise can be found, when −ɛ is small enough, from the largest root of f(n) = 1 or ln f = 0. For example, for −ɛ = 0.065, the three roots are n = 1.32, 199.8, and 1,877.6. For very small −ɛ, the sudden rise begins at about n = −1/ɛ3. Thus this n→∞ as −ɛ→0.

A rather obvious but arbitrary choice for the upper limit in the Υ′ integral, when 0 < −ɛ ≤ 0.075, is n0:

|

9 |

This integral does not diverge. For practical purposes (e.g., numerical integration), the upper limit can be taken as a constant much smaller than n0 because the integrand is near zero over a long range of n < n0. When −ɛ > 0.075, the upper limit is ∞, the integral diverges, and the metastable state does not survive.

Series Expansion of Υ′

We examine here an alternative mathematical approach to that in the above section, but it has interesting similarities. We start again with the integral in Eq. 6. Expansion of e−ɛn as a power series in ɛ, followed by term-by-term integration, leads to (the integrals are Γ functions)

|

10 |

If ɛ is positive, the signs alternate, and the series must converge because the integral in Eq. 6 does. If ɛ is negative, the signs are all positive and the series, along with the integral, diverges mathematically. However, again if ɛ is negative and small enough, physical “convergence” can be achieved, in this case by cutting off the series after an appropriate finite number of terms. We pursue this point in the following.

For suitable small negative values of ɛ, the magnitudes of both even and odd terms in Eq. 10 pass through a minimum as m increases. The value of m at the minimum, denoted by m0, is found to be the same for both even and odd terms:

|

11 |

where am is the mth term. We define s0 as the negative of the odd summand in Eq. 10 calculated from the odd m nearest the m0 found from Eq. 11. Table 2 gives values of m0 and s0 for several choices of −ɛ. For example, s0 for −ɛ = 0.08 corresponds to m = 37. The values of s0 should be compared in magnitude with the corresponding, leading term, m = 5 negative summand, −8!ɛ (also included in Table 2). If both sums in Eq. 10 are cut off at essentially m0, the s0 and −8!ɛ values in Table 2 suggest that adequate “physical” convergence will be attained for −ɛ ≤ 0.07 and possibly for −ɛ = 0.075, but not for larger values of −ɛ. The same conclusion was reached from Table 1.

Table 2.

Properties of the minimum in the odd-term summand in Eq. 10

| −ɛ | m0 | s0 | −8!ɛ |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.05 | 110.02 | 7.55 × 10−12 | 2,016 |

| 0.06 | 73.5 | 4.57 × 10−5 | 2,419.2 |

| 0.07 | 51.3 | 0.294 | 2,822.4 |

| 0.075 | 43.3 | 5.422 | 3,024 |

| 0.08 | 36.6 | 51.90 | 3,225.6 |

| 0.09 | 26.007 | 1,146.9 | 3,628.8 |

We can illustrate the above considerations by comparing, for −ɛ = 0.03, the values of Υ′ obtained by numerical integration (Eq. 9) and by summing the series in Eq. 10. The integrand f(n) in Υ′ is 0.101 at n = 130 compared with f1=187.4 at the maximum in f(n), from Table 1. Numerical integration from n = 0 to n = 130 gives Υ′ = 5,778.5. Turning to the series, Eq. 10, successive terms decrease to 0.20 for m = 13 compared with the leading m = 4 term of 2,806.88. Including the m = 13 term, we find Υ′ = 5,779.8. The agreement seems quite satisfactory in view of the approximations involved.

The close agreement found above (and also following Eq. 19, below) between the integral and series methods for Υ′ can be understood as follows. In the integral method, let the upper limit needed for the accuracy desired be n = n′ (e.g., n′ = 130 for −ɛ = 0.03, above). If we expand e−ɛn in this integral and then integrate term by term, the mth term in the resulting series, starting with m = 4, is

|

Let m′ be the largest m needed for the desired convergence in the series method (e.g., m′ = 13 for −ɛ = 0.03, above). If, for each 4 ≤ m ≤ m′, the integrand in the above integral, including the constants, is negligible for n ≥ n′, then the upper limit n′ in the integral can be replaced by ∞, as a good approximation. This change in the upper limit leads to Γ functions and the series, Eq. 10, applicable at least through m = m′.

Mean Size of Clusters and Size Distribution

Corresponding to Eqs. 4 and 5, we have

|

12 |

|

13 |

Perhaps it should be recalled here that the actual N = α−3/2n. Differentiation of these expressions leads to

|

14 |

|

15 |

These are quite general relations for open systems (1).

Eq. 14 tells us that, in passing from C to D in Fig. 1 along the metastable gas path, μ increases, ɛ decreases (becomes negative), and hence  increases: the clusters in the gas phase become larger on average as ɛ becomes more negative. Conversely, along the stable path from C to B, μ decreases, ɛ increases, and hence

increases: the clusters in the gas phase become larger on average as ɛ becomes more negative. Conversely, along the stable path from C to B, μ decreases, ɛ increases, and hence  decreases (smaller clusters).

decreases (smaller clusters).

Correspondingly, Eq. 15 states that, from C to D, P′(n) increases for n > n̄ and decreases for n < n̄ (larger clusters are formed at the expense of smaller ones). The situation is reversed on the stable path C to B.

From the series, Eq. 10, we can deduce

|

16 |

|

where

|

17 |

|

18 |

|

19 |

These series have practical use for very small |ɛ| only, because of the small number of terms.

As another numerical example, the Eq. 16 series leads to Υ′ = 4,457.4 for ɛ = −0.02, while numerical integration of Υ′ in Eq. 9 (n = 0 to 120) yields Υ′ = 4,457.0. In the same case, the series Eq. 18 gives n̄ = 24.887, compared with n̄ = 24.905 from the quotient of integrals (numerical integration) in Eq. 13 (the numerator is 111,003, using n = 0 to 150).

Of course, for any −ɛ ≤ 0.075, n̄ can be found from the quotient of integrals in Eq. 13 using numerical integration with finite upper limits on the integrals. For example, for −ɛ = 0.065, n̄ = 42.27.

Dependence of Surface Tension on Curvature

The surface tension of a spherical droplet decreases somewhat as the radius decreases (22). If this refinement is included here, N2/3 in Eq. 1 is replaced by N2/3 − const. N1/3 (ref. 1, Part I, p. 71). This alters the details in Table 1 and Fig. 2, but not the qualitative features. However, in the series expansion of Υ′, the integrals are no longer simple Γ functions.

R.V.C. was supported in part by the National Science Foundation through Grant DMR 9701740.

References

- 1. Hill T L. Thermodynamics of Small Systems. New York: Dover; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hill T L. Statistical Mechanics. New York: Dover; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Volmer M. Kinetik der Phasenbildung. Dresden, Germany: Steinkopff; 1939. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frenkel J. Kinetic Theory of Liquids. New York: Dover; 1955. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smoluchowski R. In: Handbook of Physics. 2nd Ed. Condon E U, Odishaw H, editors. New York: McGraw–Hill; 1967. pp. 8-97–8-111. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reiss H. J Chem Phys. 1952;20:1216–1227. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lothe J, Pound G M. J Chem Phys. 1962;36:2080–2085. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zettlemoyer A C. Nucleation. New York: Dekker; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reiss H, Katz J L. J Chem Phys. 1967;46:2496–2499. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rao M, Berne B J. Astrophys and Space Sci. 1979;65:39–46. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chekmarev S. Chem Phys Lett. 1985;120:531–536. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Langer J S. Ann Phys. 1967;41:108–157. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Volmer M, Flood H. Z Phys Chem (Leipzig) 1934;170:273–285. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johansson C H, Hagsten G. Ann Phys. 1937;28:520–527. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmidt-Rohr K, Spiess H W. Phys Rev Lett. 1991;66:3020–3023. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.66.3020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cicerone M T, Ediger M D. J Chem Phys. 1995;103:5684–5692. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Böhmer R, Hinze G, Diezemann G, Geil B, Sillescu H. Europhys Lett. 1996;36:55–60. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schiener B, Böhmer R, Loidl A, Chamberlin R V. Science. 1996;274:752–754. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chamberlin R V, Schiener B, Böhmer R. Mater Res Soc Symp Proc. 1997;455:117–125. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Richert R. J Phys Chem B. 1997;101:6323–6326. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Langer J S. Ann Phys. 1969;54:258–275. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ono S, Kondo S. In: Encyclopedia of Physics. Flügge S, editor. Vol. 10. Berlin: Springer; 1960. pp. 134–280. [Google Scholar]