Abstract

A lactonohydrolase from Fusarium oxysporum AKU 3702 is an enzyme catalyzing the hydrolysis of aldonate lactones to the corresponding aldonic acids. The amino acid sequences of the NH2 terminus and internal peptide fragments of the enzyme were determined to prepare synthetic oligonucleotides as primers for the PCR. An approximate 1,000-base genomic DNA fragment thus amplified was used as the probe to clone both genomic DNA and cDNA for the enzyme. The lactonohydrolase genomic gene consists of six exons separated by five short introns. A novel type of RNA editing, in which lactonohydrolase mRNA included the insertion of guanosine and cytidine residues, was observed. The predicted amino acid sequence of the cloned lactonohydrolase cDNA showed significant similarity to those of the gluconolactonase from Zymomonas mobilis, and paraoxonases from human and rabbit, forming a unique superfamily consisting of C-O cleaving enzymes and P-O cleaving enzymes. Lactonohydrolase was expressed under the control of the lac promoter in Escherichia coli.

Keywords: hydrolase/paraoxonase/superfamily/evolution

Lactone chemicals such as A-factor (2-isocapryloyl-3R-hydroxymethyl-γ-butyrolactone) (1), virginiae butanolide (2), and N-(β-oxo-acyl) homoserine lactone (3–5) play important roles in the biological world. A-factor (6), which is a low molecular-mass-autoregulating factor, is akin to hormones in eukaryotes because it switches on several phenotypes (e.g., streptomycin production, streptomycin resistance, and sporulation) at an extremely low concentration. Similar autoregulators containing a γ-lactone ring in their structures were reported recently (3, 5). Enzymes that synthesize or degrade these molecules must tightly control the amounts of such lactone autoregulators. However, there have been no reports on the structures and functions of lactone-hydrolyzing enzymes at the molecular level, except for one on the gluconolactonase from Zymomonas mobilis (7).

We previously reported (8) that a fungus, Fusarium oxysporum AKU 3702, produces a unique lactone-hydrolyzing enzyme (lactonohydrolase) that catalyzes the reversible hydrolysis of various aldonate lactones and aromatic lactones. The purified enzyme stereospecifically hydrolyzes aldonate lactones such as d-galactono-γ-lactone and l-mannono-γ-lactone, and also catalyzes the enantioselective hydrolysis of d-pantoyl lactone, which resembles aldonate lactones in chemical structure. When racemic pantoyl lactone serves as a substrate for the lactonohydrolase of F. oxysporum, only d-pantoyl lactone can be converted to d-pantoic acid without any modification of the l enantiomer, resulting in the transformation of the racemic mixture into d-pantoic acid and l-pantoyl lactone (9). After the removal of l-pantoyl lactone from this mixture, e.g., by solvent extraction, the remaining pantoic acid can be easily converted to d-pantoyl lactone by heating under acidic conditions. Because this enzyme shows not only high activity but also high stability, it can be called a “superbiocatalyst”. This enzymatic process has been shown to be applicable for the industrial production of d-pantoyl lactone (9, 10).

In this paper, we report the structures of cDNA and genomic DNA of this lactonohydrolase, a unique type of RNA-editing, its expression in Escherichia coli, and suggest an evolutionary relationship between a C-O cleaving enzyme and a P-O cleaving enzyme.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Microorganisms and Cultivation.

The lactonohydrolase gene was isolated from F. oxysporum (AKU 3702, Faculty of Agriculture, Kyoto University) (8). E. coli JM109 (recA1, endA1, gyrA96, thi-1, hsdR17, supE44, relA1, Δ(lac-proAB)/F′[traD36, proAB, laclqZΔM15]), JM105 (endA1, supE, sbcB15, thi, rpsL, Δ(lac-proAB)/F′[traD36, proAB+, lac Iq, lacZΔM15]), and XL1-Blue MRF′ (Δ(mcrA)183, Δ(mcrCB-hsdSMR-mrr)173, endA1, supE44, thi-1, recA, gurA96, relA1, lac, λ−, [F′, proAB, lacIq ZΔM15, Tn10, (tetr)]) were the hosts for pUC plasmid transformation and phage M13 mp18/19 propagation (11). E. coli transformants were grown in 2× YT medium (1.6% tryptone/1% yeast extract/0.5% NaCl) (11).

F. oxysporum collected from an agar slant was inoculated into a test tube containing 5 ml of a medium consisting of 10 g of glycerol, 5 g of Polypepton (Daigo, Osaka, Japan), 5 g of yeast extract (Oriental Yeast, Tokyo, Japan), and 5 g of corn steep liquor (Shono Starch, Suzuka, Japan) per liter of tap water (pH 6.0) and then incubated at 28°C for 24 h with reciprocal shaking. The subculture was then inoculated into a 2-liter shaking flask containing 500 ml of a medium (pH 6.0) (which consisted of 30 g of glycerol/5 g of yeast extract/5 g of corn steep liquor per liter of tap water), and incubated at 28°C for 4 days with aeration. Cells were harvested by filtration, washed twice with water, and then stored at −80°C until use.

Isolation of Peptide Fragments and Their Sequencing.

The lactonohydrolase (30 nmol), which was purified according to the procedure previously reported (8), was digested with lysylendopeptidase in 50 mM Tris⋅HCl buffer (pH 9.0) containing 4 M urea for 12 h at 30°C at a substrate/enzyme ratio of 100:1. The peptides obtained on this digestion were separated by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) on a Cosmosil 5C18-AR column (4.6 by 250 mm; Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan) and eluted with a linear gradient of acetonitrile (0–50% by vol) in the presence of 0.1% (by vol) trifluoroacetic acid at the flow rate of 1.0 ml/min. The peptides isolated were sequenced with a gas-liquid-phase protein sequencer (Applied Biosystems model 477A).

Preparation of Genomic DNA.

Total DNA of F. oxysporum was isolated by a modification of the method of Malardier et al. (12). The following procedure was carried out: liquid N2 was added to frozen cells (10–20 g), and the cells were ground with a ceramic pestle and mortar. The ground cells were suspended in 100 ml of 10 mM Hepes (pH 6.9) containing 200 mM EDTA and 1% SDS. The mixture was then incubated for 2 h at 65°C. DNA was purified by extracting the lysate with phenol/chloroform (1/1; vol/vol), precipitated with 2-propanol, treated with RNase, and reprecipitated with ethanol.

Cloning of a Partial Lactonohydrolase Genomic DNA. Oligonucleotide primers were synthesized based on the amino acid sequences of the NH2 terminus and internal fragments generated with lysylendopeptidase. The amino acid sequence, Phe-His-Val-Tyr-Asp-Glu-Glu-Phe-Tyr-Asp, was used to model the oligodeoxynucleotide pool 5′-AAAAGCTTCCAC(T)GTCTAC(T)GAC(T)GAA(G)GAA(G)TTC(T)TAC(T)GAC(T)GT-3′ (sense strand), and Asp-Gly-Val-His-Val-Trp-Asn-Pro to model 5′-GGCTTGCTGCAGGGG(A)TTCCAA(C, G,T)ACG(A)TGA(C, G,T)ACA(C, G,T)CCG(A)TC-3′ (antisense strand). These oligonucleotides were synthesized by the phosphoramidite method (13) by using an Applied Biosystems model 381A automated synthesizer. DNA was amplified by means of the PCR by using a thermal cycler (Perkin–Elmer). The reaction mixtures comprised 2.5 μg of template DNA, 250 pmol of each oligonucleotide pool, and Thermus thermophilus DNA polymerase (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan) in a total volume of 50 μl. One thermal cycle consisted of 92°C for 1 min, 55°C for 2 min, and 73°C for 3 min. A total of 30 cycles were performed. The gel-purified PCR-synthesized product (1,000 bp) was cloned into the PstI– HindIII sites of M13 mp18 replicative form DNA and designated as pFLP10. Nucleotides were sequenced by chain termination (14) by using Sequenase version 2 (United States Biochemical). Deoxy-ITP or 2′-deoxy-7-deaza-GTP was substituted for dGTP during M13 sequencing to minimize compression. The deduced amino acid sequence of the insert DNA in pFLP10 agreed with those of the sequenced peptides of lactonohydrolase. The gel-purified PCR product was further used as a radiolabeled probe by random priming (15) to clone the full length genomic DNA and cDNA of lactonohydrolase.

Cloning of the Lactonohydrolase Genomic Gene from F. oxysporum.

After digestion of the total DNA with several restriction endonucleases, Southern hybridization (16) was carried out by using the above probe with the following modifications. Hybridization was performed in a solution comprising 40% (by vol) formamide, 6× SSC (1× SSC = 0.15 M NaCl and 15 mM sodium citrate) and 0.1% (mass/vol) SDS at 42°C for 12 h, and the nitrocellulose filter was washed twice at 50°C in 4× SSC containing 0.1% (mass/vol) SDS. A single 9-kb band was detected when total DNA was digested with EcoRI. This fragment was recovered by the procedure described by Chen and Thomas (17) and ligated with EcoRI-digested pUC19. The ligation mixture was introduced by transformation into E. coli JM109 and then colony hybridization (18) for the screening of clones containing the restriction fragment was performed.

Preparation of Poly(A)+ RNA and Construction of cDNA Libraries.

Total RNA was isolated from the Fusarium cells ground in liquid nitrogen by the acid-guanidium-phenol-chloroform (AGPC) method (19). Poly(A)+ RNA was separated on an oligo(dT)-cellulose column with a mRNA purification kit (Pharmacia).

A cDNA library consisting of primary recombinants was constructed from F. oxysporum mRNA in phage vector λgt10 by using a cDNA Synthesis System Plus and a cDNA Cloning System λgt10 (Amersham). The cDNA library was screened by plaque hybridization (20) using the above probe. The final sequences of the cloned genomic DNA and cDNA for lactonohydrolase were determined in both orientations.

Determination of 5′-End of the Lactonohydrolase cDNA.

The nucleotide sequences of the insert DNA in each positive cDNA clone hybridizing with the probe were determined by chain termination sequencing (14). However, these cDNA clones did not contain a start codon, although they contained the sequence corresponding to the amino acid sequence determined from the purified enzyme of F. oxysporum. Therefore, the rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) method was used to extend 5′-end of the lactonohydrolase cDNA. The cDNA fragment containing the start codon was subcloned by using a Marathon cDNA amplification kit (CLONTECH) and a TA cloning kit (Invitrogen). This fragment was cloned into the EcoRI site of pUC18 designated as pFLC40 and sequenced.

Preparation of Crude Extracts of E. coli Transformants.

The recombinant E. coli JM109 containing pFLC40E was cultured aerobically to late log phase in 10 ml of 2 × YT medium containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin in a 100-ml test tube at 28°C or 37°C and then transferred to 100 ml of the same medium in a 500-ml shaking flask with isopropyl β-thiogalactopyranoside at a final concentration of 1 mM to induce the lac promoter. After a further 7-h or 12-h cultivation, the cells were harvested by centrifugation, suspended in 4 ml of 0.1 M Pipes (pH 7.0), disrupted by sonication for 5 min (19 kHz; Insonator model 201M, Kubota, Tokyo), and then centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min. The resulting supernatants were used for the enzyme assay. SDS/PAGE was performed by the method of Laemmli (21). To confirm that the expressed protein was lactonohydrolase, its NH2 terminus was determined with the Applied Biosystems gas-phase amino acid sequencer.

Enzyme Assay and Definition of the Unit.

The standard reaction mixture (1.44 ml) for assaying the lactonohydrolase activity contained 0.24 ml of 10% d-pantoyl lactone and an appropriate amount of the enzyme in 0.1 M Pipes (pH 7.0). The reaction was performed at 30°C for an appropriate time and stopped by adding 2 mM EDTA in methanol. The amount of d-pantoic acid formed in the reaction mixture was determined by HPLC under the same conditions as described previously (8). One unit of the enzyme was defined as the amount catalyzing the formation of 1 μmol pantoic acid/min from pantoyl lactone under the above conditions (8). The protein concentration was determined by the method of Bradford by using BSA as a standard protein (22).

Antiserum Preparation and Western Blot Analysis.

Antibodies recognizing lactonohydrolase were obtained by immunizing rabbits with the purified native lactonohydrolase, first with complete Freund adjuvant (Difco) and then with incomplete Freund adjuvant as a booster 2 weeks after the first immunization. The IgG fraction was obtained by passage through a protein A affinity column.

Cell extracts prepared by sonication were subjected to SDS/PAGE and then transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane by a standard procedure (11). Western blots were probed with anti-lactonohydrolase antiserum and then with anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to horseradish peroxidase. Probing with the antibodies and color development were carried out as described by the supplier (Bio-Rad).

RESULTS

Isolation and Characterization of the Lactonohydrolase cDNA.

The amino acid sequences of the peptides were determined through digestion of the F. oxysporum lactonohydrolase with lysylendopeptidase. Based on the sequences of two internal peptides, two oligonucleotide primers were designed as described in Materials and Methods; the sense primer (containing a HindIII site) synthesized was a 38-mer with 256 variants (corresponding to amino acid positions 48–57 shown in Fig. 1), and the antisense primer was a 35-mer with 512 variants (corresponding to amino acid positions 326–333 shown in Fig. 1). The nucleotide sequences corresponding to both primers were detected in pFLP10, which contains the 1,000-bp fragment generated by PCR amplification.

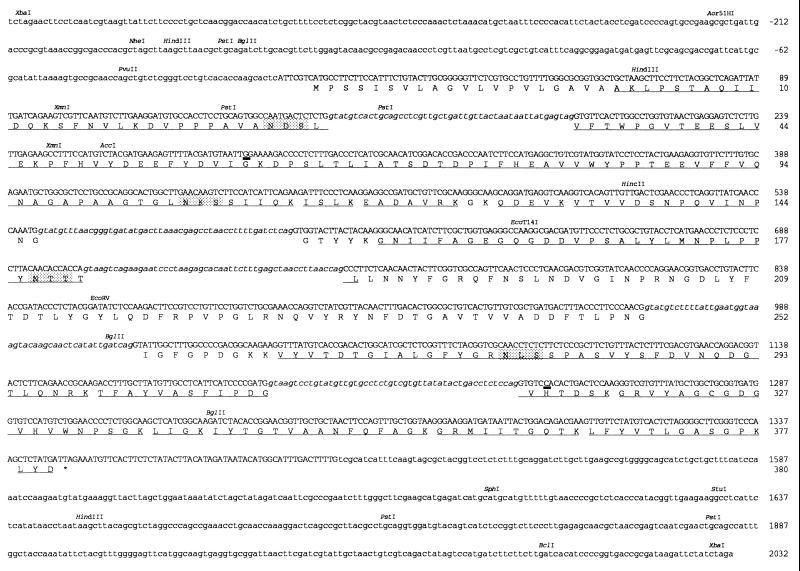

Figure 1.

Nucleotide and amino acid sequences of the F. oxysporum lactonohydrolase. The whole nucleotide sequence is derived from the genomic DNA except for two bases (i.e., 287G and 1247C). The nucleotide positions of two editing sites, in which the sequence differences were found between the genomic DNA and cDNA, are bold-underlined; 287G and 1247C are derived from the cDNA. The deduced amino acid sequence is numbered from the NH2 terminus (Ala) of the mature enzyme. The underlined amino acid sequences were determined by Edman degradation. The stop codon [TAG] is indicated by an asterisk. The cleavage site between the signal sequence and lactonohydrolase is indicated by an upward arrow. Four introns, inferred by comparison with the cDNA sequence, are shown in lowercase letters. Uppercase letters indicate six exons. The potential polyadenylation signal in the 3′-noncoding region is boxed. The presumed N-glycosylated asparagine residues are indicated by shading.

The lactonohydrolase cDNA was selected from the F. oxysporum cDNA library through several hybridizations by using the radiolabeled PCR-synthesized probe, but the cDNA prepared at first did not contain the start codon, although it encoded the NH2-terminal amino acid sequence of the lactonohydrolase from Fusarium. Therefore, to obtain a cDNA containing the start codon, we used the rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) method. The EcoRI fragment of cDNA contained an ORF, which comprised 400 amino acids (Mr 43, 206), starting with ATG (methionine) and terminating with TAG, and encoded amino acid sequences corresponding precisely to those of the peptide fragments of lactonohydrolase from Fusarium (underlined in Fig. 1). A potential alternative poly(A)+ signal sequence, AATACA, was present, although a canonical polyadenylation signal (AATAAA) (23) was not found.

On determination of the N-linked sugar chains of the Fusarium lactonohydrolase by two-dimensional mapping and 1H-NMR spectroscopy (unpublished data), the positions of four asparagine residues (asparagines 28, 106, 179, and 277 in Fig. 1) were found to be glycosylation sites.

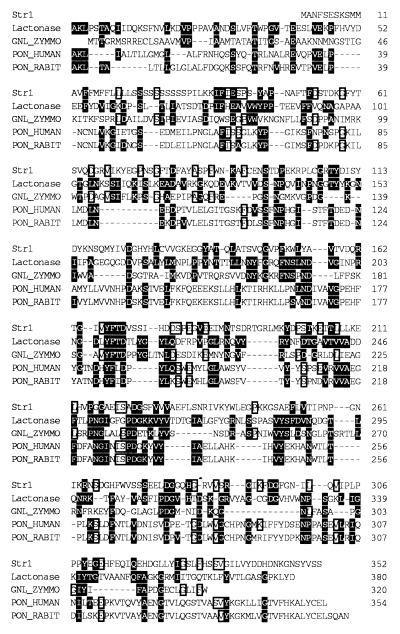

A computer-aided search of the protein sequence databases revealed that lactonohydrolase was significantly similar to the gluconolactonase (28.9%) from Z. mobilis (7), paraoxonases (25.3%) from human and rabbit (24), and strictosidine synthase (15.9%) from Catharanthus roseus (25) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Alignment of the amino acid sequences of Fusarium lactonohydrolase, Zymomonas gluconolactonase, human paraoxonase, and Catharanthus strictosidine synthase. Str1, strictosidine synthase; lactonase, Fusarium lactonohydrolase; GNL_ZYMMO, Zymomonas gluconolactonase; PON_HUMAN, human paraoxonase; PON_RABIT, rabbit paraoxonase. Residues highlighted in reverse type are conserved in the Fusarium lactonohydrolase and all the other enzymes. Identical residues in Catharanthus strictosidine synthase and the other enzymes are boxed.

Isolation and Characterization of the Lactonohydrolase Genomic Gene.

Southern hybridization against the Fusarium genomic DNA digested with various restriction enzymes revealed that one fragment (9 kb), generated by digestion with EcoRI, hybridized with the probe. The EcoRI-digested 9-kb fragment was ligated with EcoRI-digested pUC19. The plasmid containing the 9-kb EcoRI fragment was designated pFLG30T. Using E. coli XL1-Blue MRF′ as a host, we sequenced a 2.4-kb XbaI fragment that was obtained by digesting of the 9-kb EcoRI fragment with XbaI and found to hybridize with the probe. Nucleotide sequencing, as described below, revealed that the entire lactonohydrolase genomic gene was present in the XbaI fragment, and its nucleotide sequence exactly agreed with the cDNA sequence except for differences at two positions; guanine-238 and cytosine-997 in cDNA were not present in the genomic DNA. The lactonohydrolase genomic gene was composed of five introns and six exons (Fig. 1). Each intron began with GT and ended with AG, which are common features of eukaryotic splice junctions (26).

Expression of the Lactonohydrolase cDNA in E. coli.

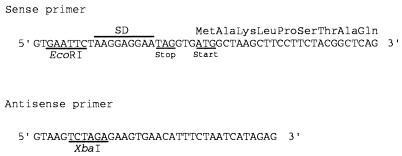

The cloned lactonohydrolase cDNA was ligated to E. coli expression vector pUC18 after modification of the cDNA as follows. We improved the sequence upstream from the GCT codon [which corresponded to the NH2-terminal alanine residue of the purified enzyme of F. oxysporum (8)] by PCR with pFLC40 as a template and two oligonucleotides as primers (Fig. 3). The sense primer comprised an EcoRI recognition site, a ribosome-binding site, a TAG stop codon in-frame with the lacZ gene in pUC18, and 24 nucleotides (61–84 in Fig. 1) of the lactonohydrolase gene starting with the ATG start codon 7 nucleotides downstream from the ribosome-binding site. The antisense primer comprised 29 nucleotides of the gene (complementary to nucleotides 1340–1368 in Fig. 1) 14 nucleotides downstream from the end of the reading frame and an XbaI recognition site. The plasmid designated as pFLC40E was constructed by ligation of the PCR product with pUC18/EcoRI–XbaI and was transformed into E. coli JM109.

Figure 3.

Sequences of the oligonucleotides used for expression of the lactonohydrolase cDNA.

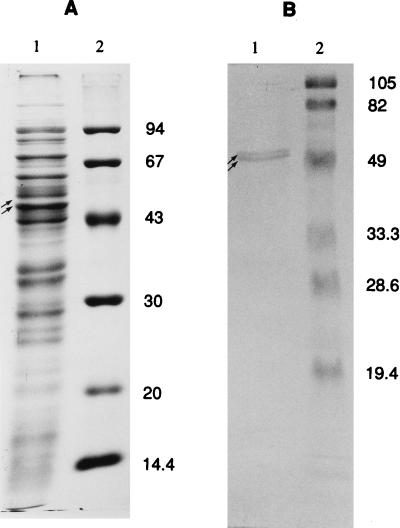

In this construction, the lactonohydrolase gene was under the control of the lac promoter. We analyzed the production of the lactonohydrolase in the supernatant of the sonicated extracts by SDS/PAGE. When E. coli carrying pFLC40E was cultured in the presence of isopropyl β-thiogalactopyranoside at 37°C, lactonohydrolase activity was observed in the supernatant of the sonicated cell-free extracts but not in the pellet obtained by centrifugation at 12,000 × g. When the transformant was cultured for 12 h, the specific activity in the supernatant of the sonicated cell-free extracts was 1.73 units/mg. It also showed higher activity (1.94 units/mg) under the same cultural condition except that 28°C was used instead of 37°C as cultivation temperature. Moreover, when the transformant was cultured for 12 h at 28°C, during which isopropyl β-thiogalactopyranoside was added 4 h from the start, the maximum level of lactonohydrolase activity (2.25 units/mg) was obtained in the supernatant. No lactonohydrolase activity was detected in the negative control experiment, in which the transformant harboring only pUC18 was assayed. The lactonohydrolase formation in the supernatants of cell-free extracts of the pFLC40E-carrying transformants cultured at 28°C was examined by SDS/PAGE. The E. coli transformant carrying pFLC40E expressed proteins of 49 kDa and 51 kDa (Fig. 4a), both of which were not produced by the transformant carrying pUC18 (data not shown). Western blot analysis with anti-lactonohydrolase antiserum for the transformant demonstrated that the two proteins corresponding to ≈49 kDa and 51 kDa were both lactonohydrolase (Fig. 4b). The 49 kDa protein is likely to be generated from the 51-kDa protein by proteases in the cells.

Figure 4.

Expression of lactonohydrolase in E. coli transformant. (A) Coomassie brilliant blue-stained gel showing electrophoretically separated proteins. The extra bands corresponding to the lactonohydrolase are indicated by arrows. Lane 2 was loaded with the following molecular mass standards (Pharmacia): phosphorylase (94 kDa), BSA (67 kDa), ovalbumin (43 kDa), carbonic anhydrase (30 kDa), and soybean trypsin inhibitor (20.1 kDa). (B) Western blot of a similar gel after immunostaining with the antibodies specific for the lactonohydrolase from F. oxysporum. Lane 2 was loaded with the following molecular mass standards (prestained SDS/PAGE standards low range; Bio-Rad): phosphorylase (105 kDa), BSA (82 kDa), ovalbumin (49 kDa), carbonic anhydrase (33.3 kDa), soybean trypsin inhibitor (28.6 kDa), and lysozyme (19.4 kDa).

DISCUSSION

Lactone studies have recently received much attention in diverse fields such as pathology, applied microbiology, and prebiotic biology: (i) homoserine lactone molecules serve as signals in quorum sensing, a system for cell density-dependent expression of specific sets of genes (4, 5); (ii) a lactone-degrading enzyme, lactonohydrolase, has been used for the industrial production of d-pantoyl lactone from racemic pantoyl lactone (8); and (iii) the components of CoA (which seems to have acted in this capacity very early in the development of life on Earth and also now occurs in a number of enzymes) have been shown to be probable prebiotic compounds containing pantoyl lactone (27). However, this is only the second analysis of lactone-hydrolyzing enzymes at the molecular level; the only previous one is on the gene cloning of gluconolactonase from Zymomonas mobilis (7).

Comparison of the Fusarium genomic DNA and cDNA sequences indicated that the transcript encoding lactonohydrolase undergoes the process of RNA editing. Based on the nucleotide sequence information, the lactonohydrolase cDNA has two inserted nucleotides, guanine-238 and cytosine-997 in cDNA (nucleotide positions between 286 and 287 and between 1245 and 1246, respectively, in Fig. 1), which were not found in the genomic DNA. This is the first report of a mode of RNA editing that generates a single G and a single C insertion at each position in mRNA, although various other modes of RNA editing such as insertion, deletion, and substitution are known (28). The lactonohydrolase genomic DNA does not contain 238G and 997C included in the cDNA. These insertions in the mRNA of lactonohydrolase are indispensable for production of the lactonohydrolase. The complementarity in each surrounding position (i.e., TGGA and TCCA, which correspond to nucleotide positions 286–288 and 1244–1246, respectively, the inserted nucleotides being underlined) may be related with the insertional RNA editing. However, the detail mechanism underlying the RNA editing remains unknown, while small RNAs are known to guide the insertion and deletion of uridines in mitochondrial transcripts of trypanosomes (29). This discovery of the RNA editing is significant, and this information also could contribute to elucidation of the genetics of the fungi kingdom, which lags far behind that in the case of the animal and plant kingdoms.

The NH2-terminal amino acid of the purified enzyme from F. oxysporum was identified as alanine (amino acid position 21 in the sequence predicted from cDNA in Fig. 1). Therefore, the presumed mature lactonohydrolase, which is produced in F. oxysporum, consists of 380 amino acid residues, although the ORF of the cDNA encodes 400 amino acids. The presumed signal peptide would exist just before the NH2-terminal amino acid sequence of the lactonohydrolase. The signal cleavage site is between Ala/20 and Ala/21. A typical signal peptide (30) was found in the N-terminal amino acid sequence deduced from the lactonohydrolase cDNA; three polar amino acids [Ser-−18, Ser-−17, and Ser-−15; minus (−) represents the amino acid region before the NH2-terminal of the mature enzyme] followed by a hydrophobic core [from Val-−14 to Ala-−1 with a helix breaking residue (Pro-−7)]. These findings suggest that lactonohydrolase is produced as a proprotein with an additional NH2-terminal 20 amino acids, and then is subjected to the processing, resulting in the formation of the mature protein and in the deletion of the signal peptide consisting of 20 amino acids.

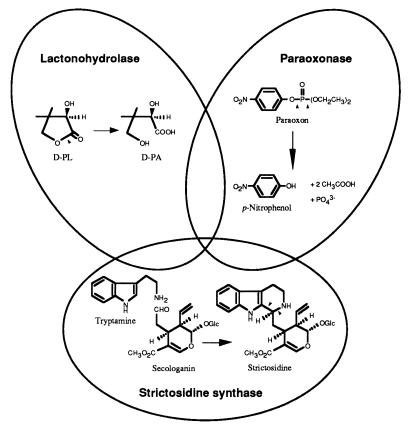

This lactonohydrolase exhibits sequence similarity to the Z. mobilis gluconolactonase (7), human serum paraoxonase (24), and C. roseus strictosidine synthase (25), suggesting an evolutionary relationship among these molecules (Fig. 5). This sequence similarity among the lactonohydrolase, paraoxonase, and strictosidine synthase has never been previously reported. We examined whether the lactonohydrolase has paraoxonase activity or not, but we could not detect any activity (data not shown).

Figure 5.

A novel superfamily. The sites (in the structural formula) cleaved by each enzyme are indicated by arrows. d-PL, d-pantoyl lactone; d-PA, d-pantoic acid.

Many organophosphorus compounds are potent cholinesterase inhibitors: parathion, chlorpyrifos, and diazinon used as pesticides are unfortunately also nerve agents; soman and sarin also are known to be nerve agents (31). Parathion, chlorpyrifos, and diazinon are bioactivated to potent cholinesterase inhibitors by cytochrome P450 systems, and the resultant toxic oxon forms can be hydrolyzed by paraoxonase, which also catalyzes hydrolysis of soman and sarin. Therefore, studies on the paraoxonase in human serum (32), which hydrolyzes paraoxon (the metabolite of parathion), are important and have been extensive (31–33). Further biochemical research including three-dimensional analysis on this lactonohydrolase/paraoxonase superfamily will allow major advances in our understanding of their biological function (including protection against toxicity due to organophosphate substrates) as well as their structure.

Strictosidine synthase (34, 35) catalyzes the condensation of tryptamine with secologanin to form strictosidine, which is involved in the first key step of the biosynthesis on indole alkaloid in C. roseus. It is interesting to note that this novel superfamily overlaps the hydrolase (EC 3) and lyase (EC 4) classes, both of which are defined according to the EC number category (36) by using criteria such as substrate specificity and physicochemical properties: the former class contains gluconolactonase (EC 3.1.1.17) and paraoxonase (arylesterase; EC 3.1.8.1); the latter contains strictosidine synthase (EC 4.3.3.2). Although paraoxonase and strictosidine synthase as well as lactonohydrolase are very important enzymes, biochemical analyses of their reaction mechanisms, including identification of the amino acids that are critical for enzyme activity, never have been performed. This initial report on the existence of a novel superfamily consisting of C-O cleaving enzymes and P-O cleaving enzymes could provide invaluable information on each reaction mechanism. Furthermore, comparison of their reaction mechanisms could provide new insight for the construction of unique catalysts for the hydrolysis (or synthesis) of the C-O and P-O bonds.

We also succeeded in active expression of the lactonohydrolase gene in E. coli under the control of the lac promoter. This expression system could be useful for determination of the active amino acids in this enzyme by site-directed mutagenesis. Further characterization of the Fusarium lactonohydrolase will be significant not only in basic, but also in applied research, to better understand the molecular basis of homeostasis of lactone chemicals as an autoinducer in the former and the industrial production of pantoyl lactone in the latter.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Dr. Hideaki Yamada, Emeritus Prof. of Kyoto University for his warm encouragement and invaluable discussions during the course of this work. We thank Dr. David Kehoe (Carnegie Institution of Washington, Stanford) for his critical reading of this manuscript. We thank Prof. Haruhiko Kawasaki (Osaka Prefectural University) for the valuable discussions. We also are grateful to Dr. Akihiko Fujie and Dr. Yuichiro Takagi (Stanford University) for their continuous encouragement. M.S. is a research fellow of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

Footnotes

References

- 1. Beppu T. Trends Biotechnol. 1995;13:264–269. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7799(00)88961-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Okamoto S, Nakamura K, Nihira T, Yamada Y. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:12319–12326. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.20.12319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pesci E C, Iglewski B H. Trends Microbiol. 1997;5:132–134. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(97)01008-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schaefer A L, Val D E, Hanzelka B L, Cronan J E, Jr, Greenberg E P. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:9505–9509. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Swift S, Throup J P, Williams P, Salmond G P C, Stewart G S A B. Trends Biochem Sci. 1996;21:214–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khokhlov A S, Tovarova I I, Borisova L N, Pliner S A, Shevchenko L N, Kornitskaia EIa, Ivkina N S, Rapoport I A. Dokl Akad Nauk SSSR. 1967;177:232–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kanagasundaram V, Scopes R. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1171:198–200. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(92)90120-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shimizu S, Kataoka M, Shimizu K, Hirakata M, Sakamoto K, Yamada H. Eur J Biochem. 1992;209:383–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb17300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shimizu S, Ogawa J, Kataoka M, Kobayashi M. Adv Biochem Eng Biotechnol. 1997;58:45–87. doi: 10.1007/BFb0103302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shimizu S, Kataoka M. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1996;650:650–658. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb33270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. 2nd Ed. Plainview, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malardier L, Daboussi M J, Julien J, Roussel F, Scazzocchio C, Brygoo Y. Gene. 1989;78:147–156. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90322-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beaucage S L, Caruthers M H. Tetrahedron Lett. 1981;22:1859–1862. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feinberg A P, Vogelstein B. Anal Biochem. 1983;132:6–13. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(83)90418-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Southern E M. J Mol Biol. 1975;98:503–517. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(75)80083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen C W, Thomas C A., Jr Anal Biochem. 1980;101:339–341. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(80)90197-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grunstein M, Hogness D S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1975;72:3961–3965. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.10.3961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Benton W D, Davis R W. Science. 1977;196:180–182. doi: 10.1126/science.322279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laemmli U K. Nature (London) 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bradford M M. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Proudfoot N J, Brownlee G G. Nature (London) 1976;263:211–214. doi: 10.1038/263211a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hassett C, Richter R J, Humbert R, Chapline C, Crabb J W, Omiecinski C J, Furlong C E. Biochemistry. 1991;30:10141–10149. doi: 10.1021/bi00106a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McKnight T D, Roessner C A, Devagupta R, Scott A I, Nessler C L. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:4939. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.16.4939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Breathnach R, Chambon P. Annu Rev Biochem. 1981;50:349–383. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.50.070181.002025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Keefe A D, Newton G L, Miller S L. Nature (London) 1995;373:683–685. doi: 10.1038/373683a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Covello P S, Gray M W. Trends Genet. 1993;9:265–268. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(93)90011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stuart K, Allen T E, Heidmann S, Seiwert S D. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997;61:105–120. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.61.1.105-120.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Watson M E. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:5145–5164. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.13.5145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davies H G, Richter R J, Keifer M, Broomfield C A, Sowalla J, Furlong C E. Nat Genet. 1996;14:334–336. doi: 10.1038/ng1196-334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sorenson R C, Primo-Parmo S L, Kuo C L, Adkins S, Lockridge O, La Du B N. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7187–7191. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.16.7187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Humbert R, Adler D A, Disteche C M, Hassett C, Omiecinski C J, Furlong C E. Nat Genet. 1993;3:73–76. doi: 10.1038/ng0193-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mizukami H, Nordlov H, Lee S-L, Scott A I. Biochemistry. 1979;18:3760–3763. doi: 10.1021/bi00584a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bracher D, Kutchan T M. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1992;294:717–723. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(92)90746-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schomburg D, Salzmann M, editors. Enzyme Handbook 4. Berlin: Springer; 1991. [Google Scholar]