Abstract

Background

Annual surveillance mammography is recommended for follow-up of women with a history of breast cancer. We examined surveillance mammography among breast cancer survivors who were enrolled in integrated healthcare systems.

Methods

Women in this study were 65 or older when diagnosed with early stage invasive breast cancer (N = 1,762). We assessed mammography use during 4 years of follow-up, using generalized estimating equations to account for repeated measurements.

Results

Eighty-two percent had mammograms during the first year after treatment; the percentage declined to 68.5% in the fourth year of follow-up. Controlling for age and comorbidity, women who were at higher risk of recurrence by being diagnosed at stage II or receiving breast-conserving surgery (BCS) without radiation therapy were less likely to have yearly mammograms (compared to stage I, odds ratio [OR] for stage IIA 0.72, confidence interval [CI] 0.59, 0.87, OR for stage IIB 0.75, CI 0.57, 1.0; compared to BCS with radiation, OR 0.58, CI 0.43, 0.77). Women with visits to a breast cancer surgeon or oncologist were more likely to receive mammograms (OR for breast cancer surgeon 6.0, CI 4.9, 7.4, OR for oncologist 7.4, CI 6.1, 9.0).

Conclusions

Breast cancer survivors who are at greater risk of recurrence are less likely to receive surveillance mammograms. Women without a visit to an oncologist or breast cancer surgeon during a year have particularly low rates of mammography. Improvements to surveillance care for breast cancer survivors may require active participation by primary care physicians and improvements in cancer survivorship programs by healthcare systems.

KEY WORDS: breast cancer, surveillance, mammography, survivors

INTRODUCTION

As a result of improved survival and the increasing incidence of breast cancer with age, a large number of women age 65 and older in the USA are breast cancer survivors. Compared to women who have never had breast cancer, breast cancer survivors are at 2 to 6 times greater risk of a new primary cancer in the contralateral breast.1 In addition, breast cancer survivors who receive breast-conserving surgery have a 5 to 15% risk of recurrent cancer in the remaining breast tissue,1 with highest risk for those diagnosed at advanced stage2 and those who do not receive radiation therapy after breast-conserving surgery3,4 or adjuvant systemic therapy.5

Surveillance mammography is the only recommended imaging examination for the routine follow-up of women with a history of breast cancer. Routine annual mammograms are recommended by most guidelines6 with the expectation that they will ensure early detection of local recurrence and new primary breast cancers when they are treatable with favorable prognoses.

The limited number of studies examining use of surveillance mammography among survivors have found mammography is underused by survivors7–11 with steady declines during the years after diagnosis. However, the patterns of underuse and the factors associated with underuse are not well defined.

The purpose of the current study was to examine the use of mammography in a cohort of breast cancer survivors with complete information on follow-up derived from medical records and to assess the relationship between mammography use and patient and health care utilization factors. This study focuses on older women, a group at higher risk of breast cancer that is understudied.

METHODS

Data for this study were derived from the Breast Cancer Treatment Effectiveness in Older Women (BOW) study. The methodology of the BOW study has been previously described.12 The BOW study was designed to examine outcomes among women age 65 and older diagnosed and treated with incident early stage invasive breast cancer. The study was conducted among 6 health systems collaborating within the Cancer Research Network (CRN): Group Health (Washington), Kaiser Permanente (Southern California), Lovelace (New Mexico), Henry Ford Health System (Michigan), HealthPartners (Minnesota), and Fallon Clinic (Massachusetts). Institutional Review Boards at all sites approved the study. The CRN includes the research programs, enrollee populations, and data systems of 12 integrated healthcare systems across the USA.

We used automated administrative databases and medical record review at 2 study sites (HealthPartners and Fallon) and health system tumor registries at the 4 remaining sites to identify eligible patients. Eligible patients were all women aged 65 years or older who were diagnosed for the first time with histologically confirmed, early-stage breast cancer from January 1, 1990 through December 31, 1994 and who received mastectomy or breast-conserving surgery. We excluded women with a clinically active malignancy (except nonmelanoma skin cancer) diagnosed within the 5 years before or the 30 days after breast cancer diagnosis. We included all eligible patients from all sites except Kaiser Permanente, Southern California, the largest site, where we sampled 10% of the subgroup of non-Hispanic white women younger than age 80 with stage I breast cancer because including the complete sample of these patients would only marginally increase the statistical power of the study but would substantially decrease its cost efficiency. The women included in the current report were alive with no documented clinical evidence of breast cancer recurrence and enrolled with their respective health plans for at least 15 months after completion of breast cancer treatment. The original cohort included 1,859 women. Of these, 14 had no follow-up time. During the first 15 months after treatment, 11 disenrolled from their health plan, 9 died from breast cancer, 16 died from causes other than breast cancer, and 47 had a recurrence. The final cohort for this manuscript is 1,762. During the follow-up period, 359 of these women died, had a recurrence, or disenrolled: 33 died from breast cancer, 121 died from causes other than breast cancer, 149 had a recurrence, and 56 disenrolled.

DATA COLLECTION

As described in detail elsewhere,12 using an automated data collection system and trained medical records abstractors, we collected demographic, tumor, and treatment data from cancer registry, administrative, and clinical databases, as well as patient medical records. We assessed comorbidity diagnosis through medical record abstraction using the Charlson Comorbidity Index13 for the year before diagnosis with repeated assessment at 1 and 3 years after diagnosis. This index includes 18 conditions weighted to predict mortality among breast cancer patients. We excluded cancer and categorized the remaining score at each time point as 0, 1, or 2+. We abstracted from medical records the dates and indications for all mammographic examinations beginning 90 days after completion of initial breast cancer therapy (defined as the last day of breast cancer surgery, radiation therapy, or chemotherapy, whichever was the latest) and continuing for 4 years. Based on whether women had a mammogram and the type of clinician ordering the mammogram within each 1-year period, we categorized each woman as having received at least 1 mammogram ordered by a primary care physician; if no mammogram was ordered by the primary care physician, women were categorized as having a mammogram ordered by an oncologist or oncology nurse, a breast cancer surgeon, a different mechanism (such as self-referral), or not having a mammogram during the year. Within each year, we categorized each woman as having a visit to a medical or radiation oncologist or oncology nurse during the year, or no such visit but a visit to a breast cancer surgeon, or no visit to any of these specialists.

ANALYSIS

During each yearly period beginning 90 days after completion of initial therapy, we determined the proportion of women having at least 1 mammogram and identified the demographic, tumor, and treatment characteristics for women who did and did not receive mammography during that year. We also determined the proportion who received a mammogram ordered by a primary care physician. During each follow-up year, women were excluded if they developed a recurrence, died, or disenrolled from the health plan.

We fit a series of repeated-measures regression analyses to examine factors associated with use of yearly mammography, using the generalized estimating equations approach to account for the correlation of repeated measurements and to provide an estimate of the effect of time elapsed since breast cancer diagnosis. Models included year of follow-up, year of diagnosis, and study site and added race/ethnicity, primary breast cancer therapy received, tumor stage at diagnosis, category of current age at the beginning of the year, the most recent Charlson Comorbidity Index category, and indicators of visits to oncologists and breast cancer surgeons during the year. To assess the extent to which nonreceipt of mammography might be associated with serious level of illness, we included a variable indicating that the woman died during the next year of follow-up. The final model excluded from each year those women who died during the following year.

The analyses for this study were generated using SAS software (version 9.1) of the SAS System for Windows (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

A total of 1,762 women were included in the study. The majority were 70 years or older at the time of diagnosis, non-Hispanic white, diagnosed at American Joint Committee on Cancer stage I, and received either mastectomy (52.5%) or breast-conserving surgery with radiation therapy (36.4%; Table 1). Throughout the follow-up period, most women had a low burden of comorbid illnesses, and the majority of the women had a visit to an oncologist or breast cancer surgeon during each of the 4 years of follow-up. During each year, the proportion receiving mammography was lower for women age 75 or older and for those who had received breast-conserving surgery without radiation therapy. More than 90% of these women had at least 1 visit to an oncologist or breast cancer surgeon during the first year of follow-up. However, that percent steadily declined to 60% in the fourth year. Women without a visit to a medical or radiation oncologist or breast cancer surgeon during a year had particularly low rates of mammography—ranging from 38.4 to 46%.

Table 1.

Subject Characteristics and Receipt of Mammography During each of 4 Years of Follow-up

| Time since end of first course of therapy | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | Year 4 | |||||

| Characteristic | Number | Percent mammogram | Number | Percent mammogram | Number | Percent mammogram | Number | Percent mammogram |

| Total | 1,762 | 1,624 | 1,492 | 1,403 | ||||

| Current age | † | † | † | † | ||||

| Age 65–69 | 573 | 86.6 | 424 | 80.4 | 295 | 81.4 | 181 | 76.2 |

| Age 70–74 | 536 | 86.0 | 515 | 83.1 | 502 | 81.1 | 495 | 74.9 |

| Age 75–79 | 298 | 80.2 | 327 | 76.5 | 326 | 81.0 | 341 | 73.3 |

| Age 80+ | 355 | 70.4 | 358 | 65.6 | 369 | 55.3 | 386 | 52.3 |

| Most recent Charlson | * | † | † | * | ||||

| 0 | 1,209 | 83.4 | 1,069 | 78.9 | 992 | 77.2 | 869 | 71.7 |

| 1 | 473 | 80.5 | 467 | 77.1 | 428 | 71.3 | 446 | 64.3 |

| >1 | 80 | 71.3 | 88 | 58.0 | 72 | 61.1 | 88 | 58.0 |

| Race/ethnicity | † | † | ||||||

| White (non-Hispanic) | 1,431 | 83.9 | 1,317 | 78.6 | 1,207 | 74.6 | 1,135 | 69.9 |

| Asian | 52 | 69.2 | 46 | 63.0 | 42 | 69.0 | 41 | 68.3 |

| African American | 182 | 74.7 | 169 | 69.2 | 157 | 75.8 | 146 | 61.0 |

| Hispanic | 93 | 75.3 | 89 | 79.8 | 83 | 78.3 | 80 | 63.8 |

| Stage | * | |||||||

| Stage I | 1,014 | 82.3 | 962 | 79.5 | 893 | 76.1 | 848 | 69.2 |

| Stage IIA | 546 | 81.3 | 485 | 73.8 | 452 | 72.6 | 418 | 66.0 |

| Stage IIB | 202 | 80.2 | 177 | 74.0 | 147 | 72.8 | 137 | 71.5 |

| Surgery | † | † | † | † | ||||

| BCS‡ + radiation therapy | 634 | 89.0 | 613 | 86.1 | 581 | 81.1 | 555 | 81.1 |

| BCS‡ without radiation therapy | 183 | 64.5 | 156 | 60.9 | 134 | 56.0 | 121 | 56.0 |

| Mastectomy | 925 | 80.9 | 838 | 74.0 | 761 | 73.3 | 713 | 73.3 |

| Other or no surgery | 20 | 80.0 | 17 | 64.7 | 16 | 68.8 | 14 | 68.8 |

| Visits to specialists | † | † | † | † | ||||

| Visit to an oncologist | 1,160 | 88.5 | 975 | 85.1 | 815 | 84.5 | 693 | 81.2 |

| Visit to a surgeon | 432 | 81.5 | 364 | 83.2 | 301 | 84.1 | 255 | 82.4 |

| Visit to neither | 170 | 39.4 | 285 | 42.5 | 376 | 46.0 | 455 | 41.3 |

*Significant at the P < 0.05 level

†Significant at the P < 0.001 level

‡Breast-conserving surgery

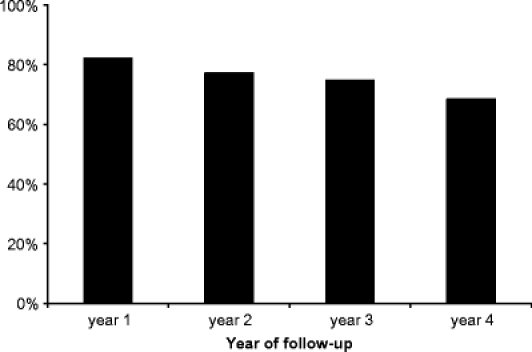

The majority of women (82.1%) had a mammogram during the first year of follow-up, but there was a steady decline in the use of mammography over time; by the fourth year of follow-up, the percent receiving a mammogram had declined to 68.5% (Fig. 1). During each year, primary care physicians ordered at least 1 mammogram for less than 17% of subjects, although the percent increased slightly from 14.7% in the first year of follow-up to 16.3% in year 4 (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Percent of women obtaining annual mammography by years since completion of breast cancer treatment (P < 0.001).

Table 2.

Distribution of Type of Clinician Ordering the Mammograms over the 4 Years of Follow-up (Mutually Exclusive)

| Year of follow-up | Primary care physician, N (%) | Breast cancer surgeon, N (%) | Oncologist or oncology nurse, N (%) | Other, N (%) | No mammogram, N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year 1 | 259 (14.7) | 532 (30.2) | 587 (33.3) | 68 (3.9) | 316 (17.9) |

| Year 2 | 240 (14.8) | 381 (23.5) | 545 (33.6) | 88 (5.4) | 370 (22.8) |

| Year 3 | 239 (16.0) | 316 (21.2) | 460 (30.8) | 100 (6.7) | 377 (25.3) |

| Year 4 | 228 (16.25) | 236 (16.8) | 373 (26.6) | 120 (8.55) | 446 (31.8) |

We examined the factors associated with use of mammography combining all follow-up years (Table 3). Two demographic characteristics were independently associated with lower odds of having an annual mammogram: age 80 or older or nonwhite ethnicity. Women at higher risk of recurrence because of being diagnosed at stage II or receiving breast-conserving surgery without radiation therapy had lower odds of receiving mammograms. The strongest association was with visits to oncologists and breast cancer surgeons; women who had a visit to an oncologist had an odds ratio (OR) of 7.4 (95% confidence interval [CI] 6.1, 9.0) of receiving a mammogram during that year and those with no oncologist visit but a visit to a breast cancer surgeon had an OR of 6.0 (CI 4.9, 7.4).

Table 3.

Multivariate Models Predicting Receipt of Mammography (All Years Combined)

| Variable | Primary model | Excluding women who die in next year | |

|---|---|---|---|

| OR* | 95% CI | OR* | |

| Age 65–69 | 1.0 | Referent | 1.0 |

| Age 70–74 | 1.0 | 0.83, 1.3 | 1.0 |

| Age 75–79 | 0.94 | 0.74, 1.2 | 0.94 |

| Age 80+ | 0.54 | 0.43, 0.68 | 0.52 |

| Charlson = 0 | 1.00 | Referent | 1.0 |

| Charlson = 1 | 0.96 | 0.80, 1.1 | 0.94 |

| Charlson > 1 | 0.65 | 0.46, 0.92 | 0.68 |

| Year before death | 0.37 | 0.27, 0.52 | NA |

| White (non-Hispanic) | 1.00 | Referent | 1.0 |

| Asian | 0.62 | 0.39, 0.96 | 0.61 |

| African American | 0.74 | 0.58, 0.93 | 0.74 |

| Hispanic | 0.85 | 0.60, 1.2 | 0.85 |

| Other/unknown | 0.45 | 0.23, 0.90 | 0.47 |

| Stage I | 1.00 | Referent | 1.0 |

| Stage IIA | 0.72 | 0.59, 0.87 | 0.69 |

| Stage IIB | 0.75 | 0.57, 1.0 | 0.72 |

| BCS† with radiation therapy | 1.00 | Referent | 1.0 |

| BCS† w/o radiation therapy | 0.58 | 0.43, 0.77 | 0.57 |

| Mastectomy | 0.87 | 0.72, 1.1 | 0.89 |

| Other or no surgery | 0.57 | 0.29, 1.1 | 0.59 |

| No visit to a breast cancer surgeon or oncologist | 1.0 | Referent | 1.0 |

| Visit to a breast cancer surgeon | 6.0 | 4.9, 7.4 | 5.8 |

| Visit to an oncologist | 7.4 | 6.1, 9.0 | 7.6 |

| Time since end of first course of therapy | 1.0 | Referent | 1.0 |

| Year 1 | |||

| Year 2 | 0.87 | 0.74, 1.0 | 0.85 |

| Year 3 | 0.88 | 0.74, 1.1 | 0.88 |

| Year 4 | 0.73 | 0.61, 0.87 | 0.72 |

Odds ratios in italics are statistically significant at the 0.05 level.

*Odds ratio, adjusted for site

†Breast-conserving surgery

Several approaches were used to examine and control for comorbidity. Women with a Charlson Comorbidity Index score greater than 1 were less likely to receive a mammogram during a year (OR 0.65, CI 0.46, 0.92). During the year before death, the OR for receipt of mammography was 0.37 (CI 0.27, 0.52). To account for this level of illness burden, we fit a model that excluded women who died in the following year, but the results were unchanged (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

This study among older women diagnosed and treated for a first primary breast cancer in integrated healthcare systems found a decline in the use of mammography over time after completion of initial therapy. We found that women at higher risk of recurrence because of being diagnosed at later stage or not receiving radiation therapy after breast-conserving therapy were less likely to receive mammograms. Women with visits to oncology or breast cancer surgery specialists during a year were much more likely to receive a mammogram during that year than those without such visits.

Several previous studies have examined use of surveillance mammograms among breast cancer survivors using a variety of data sources. Studies using the combined Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results/Medicare data have relied on Medicare claims and found rates among women age 65 and older ranging from 62%7 over 2 years of follow-up to 78% during the initial period postdiagnosis.10 In a previous study among health systems participating in the Cancer Research Network that included women age 55 and older diagnosed in 1996 and 1997, we found slightly lower rates.11 That study and those using Medicare data did not have access to medical records and were missing information on the reason for mammography orders or the type of ordering physician. A number of studies have found nonreceipt of radiation therapy after breast-conserving surgery associated with lower rates of follow-up mammography.8,9,10 Older age has also been consistently associated with lower rates.

Strengths of this study include the existence of a carefully defined sample, access to complete medical records, and a high level of follow-up. Our loss to follow-up because of disenrollment during the 4 years was 3%. There are several limitations. We ascertained receipt of surveillance mammography through medical record review. Although the women included in the study were enrollees of health plans that are responsible for their ambulatory and in-patient medical care and the medical records are thorough, we may not have captured some mammograms that did not produce negative findings if they were not documented. This would lead to an underestimate of the rate of mammography. The rates of mammography found in this study may not be generalizable to older women who receive medical care in the fee-for-service system, where rates may be lower.

Guidelines for the follow-up of women with a history of breast cancer recommend annual surveillance mammography.6 The impact of annual mammography on survival has not been evaluated in randomized trials; trials of intensive surveillance have used annual mammography as the comparison standard of care with the assumption that surveillance mammography is necessary to diagnose recurrences and new primary breast cancers at an early stage when they have the best prognosis.14,15 Population-based screening for cancers of the breast has been shown to reduce the risk of death from breast cancer,16 and routine mammograms after breast cancer diagnosis have been found to detect subsequent contralateral disease at an earlier stage than the initial breast cancer.17 Several studies have suggested better outcomes among women whose local recurrences were detected through surveillance mammography18, and recent studies of surveillance mammography in older women with breast cancer have found an association with both improved survival and reduction in cancer-related worries.19

The potential importance of surveillance mammography is highlighted by the results of 2 studies based on the experiences of the women followed in the BOW project. More than 5% developed a local or regional breast cancer recurrence during the 10 years of follow-up.20 These recurrences occurred as long as 8 years after initial diagnosis, and 43% were identified before they were symptomatic. Three percent were diagnosed with a new primary breast cancer in the contralateral breast as long as 9 years after the first diagnosis, and 62% were identified when presymptomatic. Assessment of the impact of surveillance mammography in this group found that each additional surveillance mammogram was associated with a 0.69-fold decrease in the odds of breast cancer mortality (95% CI 0.52, 0.92).21

Receipt of surveillance mammography by breast cancer survivors is a product of several factors, including physician recommendations, access to oncology specialists, the existence of clinical reminder systems, and, most importantly, the decisions of the women themselves to participate in this aspect of their medical care. Our finding of a strong association between visits to oncologists and breast cancer surgeons and receipt of surveillance mammography suggests that older breast cancer survivors who do not visit these specialists may not be aware of the role of surveillance mammography within their survivorship care. The question of when to stop surveillance mammography is not addressed in this study, although the benefits of surveillance mammography clearly extend to at least 5 years after initial diagnosis. The study also does not identify when surveillance mammography is futile because of comorbid conditions and short life expectancy. However, the low rate of surveillance mammograms in women who died within 12 months suggests that the clinicians caring for these women did not continue surveillance mammography inappropriately. Our concern remains that women who could potentially benefit from surveillance mammograms and their physicians are more likely to underappreciate when these studies still offer benefit than when they are futile.

Whether care is provided by primary care physicians alone or in collaboration with cancer specialists, older breast cancer survivors need to be aware of their increased risk of recurrences and second primaries and the potential for surveillance mammography to detect these new occurrences asymptomatically. Decisions by physicians and patients to discontinue surveillance mammography should be informed by the risks and benefits while taking into account the patient’s future life expectancy, values, and preferences.

As highlighted in the recent Institute of Medicine Report, From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition,22 there is a dearth of evidence about cancer survivors’ expectations and experiences with follow-up care. In the general population of women, physician recommendations are strongly associated with receipt of screening mammography.23 The health systems included in this study all track mammography utilization among their enrollees following the Health Plan Employer Data and Information Set guidelines. These guidelines do not call for breast cancer screening for women more than the age of 69 with no specific mention of breast cancer survivors.

In this study, women without a visit to an oncologist or breast cancer surgeon during a year had low rates of mammography during that year. Moreover, the rates of such visits steadily declined during the 4 years of follow-up. Relying on specialist care for on-going surveillance may undermine continuity of care, leaving survivors poorly prepared for long periods of potentially increased risk. In contrast to this finding, several randomized trials have demonstrated that primary care physicians can provide ongoing surveillance care to breast cancer survivors with comparable outcomes,24 similar health-related quality of life and costs, and greater satisfaction. Within 1 of the healthcare delivery systems participating in this study, implementation of an organized breast cancer screening program for its general enrolled population of women age 40 and older substantially increased the rate of mammography screening and lowered the rate of late stage diagnosis.25 Similar strategies that target healthcare systems, clinicians, patients, and public policy need to be developed for surveillance among breast cancer survivors.

CONCLUSIONS

We found that older breast cancer survivors at highest risk of recurrence were least likely to receive surveillance mammography and that women without a visit to an oncologist or breast cancer surgeon during a year had particularly low rates of mammography during the year. Improvements to surveillance care for breast cancer survivors may require active participation by primary care physicians and improvements in cancer survivorship programs by healthcare systems.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (R01 CA093772 R. Silliman, PI). A number of people assisted in the conduct of this study, including project managers, programmers, and medical record abstractors: Group Health—Linda Shultz, Kristin Delaney, Margaret Farrell-Ross, Mary Sunderland, Millie Magner, and Beth Kirlin; Meyers Primary Care Institute and Fallon Clinic—Jackie Fuller, Doris Hoyer, and Janet Guilbert; Henry Ford Health System—Sharon Hensley Alford, Karen Wells, Patricia Baker, and Rita Montague; HealthPartners—Maribet McCarty and Alex Kravchik; Kaiser Permanente Southern California—Julie Stern, Janis Yao, and Michelle McGuirel; and Lovelace Health Plan—Judity Hurley, Hans Petersen, and Melissa Roberts. Three of the authors (FW, VPQ, MUY) have received funding from pharmaceutical companies.

Conflict of interest None disclosed.

References

- 1.Grunfeld E, Noorani H, McGahan L, et al. Surveillance mammography after treatment of primary breast cancer: a systematic review. Breast. 2002;11:228–35. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Woodward WA, Strom EA, Tucker SL, et al. Changes in the 2003 American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging for Breast Cancer dramatically affect stage-specific survival. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3244–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Lash TL, Silliman RA, Guadagnoli E, Mor V. The effect of less than definitive care on breast carcinoma recurrence and mortality. Cancer. 2000;89:1739–47. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Smith BD, Gross CP, Smith GL, et al. Effectiveness of radiation therapy for older women with early breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:681–90. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group. Effects of chemotherapy and hormonal therapy for early breast cancer on recurrence and 15-year survival: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet. 2005;365:1687–717. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Khatcheressian JL, Wolff AC, Smith TH, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology 2006 update of the breast cancer follow-up and management guidelines in the adjuvant setting. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5091–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Schapira MM, McAuliffe TL, Nattinger AB. Underutilization of mammography in older breast cancer survivors. Med Care. 2000;38:281–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Lash TL, Silliman RA. Medical surveillance after breast cancer diagnosis. Med Care. 2001;39:945–55. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Geller BM, Kerlikowske K, Carney PA, et al. Mammography surveillance following breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2003;81:107–15. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Keating NL, Landrum MB, Guadagnoli E, Winer RP, Ayanian JZ. Factors related to underuse of surveillance mammography among breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:85–94. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Doubeni CA, Field TS, Yood MU, et al. Patterns and predictors of mammography utilization among breast cancer survivors. Cancer. 2006;106:2482–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Enger SM, Thwin S, Buist DS, et al. Breast cancer treatment of older women in integrated health care settings. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4377–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chron Dis. 1987;40:373–83. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.GIVIO Investigators. Impact of follow-up testing on survival and health-related quality of life in breast cancer patients: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1994;271:1587–92. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Del Truco M, Palli D, Cariddi A, et al. Intensive diagnostic follow-up after treatment of primary breast cancer: a randomized trial. JAMA. 1994;271:1593–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Nystrom L, Andersson I, Bjurstam N, et al. Long-term effects of mammography screening: updated overview of the Swedish randomised trials. The Lancet. 2002;359:909–19. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Samant RS, Olivotto IA, Jackson JSH, Mates D. Diagnosis of metachronous contralateral breast cancer. Breast J. 2001;7:405–10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Voogd AC, van Tienhoven G, Peterse HL, et al. Local recurrence after breast conservatioin therapy for early stage breast carcinoma. Cancer. 1999;85:437–46. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Lash TL, Clough-Gorr K, Silliman RA. Reduced rates of cancer-related worries and mortality associated with guideline surveillance after breast cancer therapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2005;89:61–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Geiger AM, Thwin SS, Lash TL, et al. Recurrences and second primary breast cancers in older women with early stage disease initially. Cancer. 2007;109:966–74. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Lash TL, Fox MP, Buist DSM, et al. Mammography surveillance and mortality in older breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3001–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E, eds. In: From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. Washington, DC: The National Academies; 2006.

- 23.Taplin SH, Urban N, Taylor VM, Savarino J. Conflicting national recommendations and the use of screening mammography: does the physician’s recommendation matter? J Am Board Fam Pract. 1997;10:88–95. [PubMed]

- 24.Grunfeld E, Levine MN, Julian JA, et al. Randomized trial of long-term follow-up for early-stage breast cancer: a comparison of family physician versus specialist care. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:848–55. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Taplin SH, Ichikawa L, Buist DSM, Seger D, White E. Evaluating organized breast cancer screening implementation: the prevention of late-stage disease. Cancer Epi, Biomarkers & Prev. 2004;13:225–34. [DOI] [PubMed]