Abstract

cAMP-dependent phosphorylation activates the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) in epithelia. However, the protein phosphatase (PP) that dephosphorylates and inactivates CFTR in airway and intestinal epithelia, two major sites of disease, is not certain. We found that in airway and colonic epithelia, neither okadaic acid nor FK506 prevented inactivation of CFTR when cAMP was removed. These results suggested that a phosphatase distinct from PP1, PP2A, and PP2B was responsible. Because PP2C is insensitive to these inhibitors, we tested the hypothesis that it regulates CFTR. We found that PP2Cα is expressed in airway and T84 intestinal epithelia. To test its activity on CFTR, we generated recombinant human PP2Cα and found that it dephosphorylated CFTR and an R domain peptide in vitro. Moreover, in cell-free patches of membrane, addition of PP2Cα inactivated CFTR Cl− channels; reactivation required readdition of kinase. Finally, coexpression of PP2Cα with CFTR in epithelia reduced the Cl− current and increased the rate of channel inactivation. These results suggest that PP2C may be the okadaic acid-insensitive phosphatase that regulates CFTR in human airway and T84 colonic epithelia. It has been suggested that phosphatase inhibitors could be of therapeutic value in cystic fibrosis; our data suggest that PP2C may be an important phosphatase to target.

Activity of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) Cl− channel requires ATP and is regulated by cAMP-dependent phosphorylation of multiple serine residues in the R domain (1–10). Although its activation by nucleotides and cAMP-dependent protein kinase has been studied extensively, its inactivation by phosphatases is less well understood.

Four major classes of serine/threonine protein phosphatases have been described: PP1, PP2A, PP2B, and PP2C. These enzymes differ in their substrate specificity, divalent cation requirement, and sensitivity to inhibitors (11–14). For example, PP1 and PP2A are inhibited by okadaic acid, PP2B is regulated by Ca2+/calmodulin and is inhibited by FK506 (15), and PP2C requires Mg2+ or Mn2+ for activity. We previously showed that PP2A could dephosphorylate CFTR in vitro and inactivate CFTR Cl− channels in excised patches of membrane from NIH 3T3 cells expressing CFTR (6). However inactivation was much slower in excised patches than in intact cells, suggesting that another phosphatase might regulate CFTR in intact cells, perhaps a cytosolic phosphatase that was not present in excised membrane patches. Parallel studies revealed that PP1 and PP2B did not dephosphorylate or inactivate CFTR (6). Okadaic acid and calyculin A, two cell-permeant inhibitors of PP1 and PP2A, have been used to examine regulation of CFTR in intact cells. For example, in guinea pig cardiac myocytes, CFTR was regulated by an okadaic acid-sensitive phosphatase, as well as by an okadaic acid-insensitive phosphatase that the authors suggested might be PP2C (7). In human sweat ducts, an okadaic acid-sensitive phosphatase was largely responsible for inactivating CFTR (16). Because these studies suggested that regulation of CFTR by phosphatases might be tissue specific, it was important to ask which phosphatases might regulate CFTR in airway epithelia, a site of significant disease in cystic fibrosis. The goals of the present study were to examine phosphatase regulation of CFTR in human airway and intestinal epithelia and to test whether PP2C could dephosphorylate and inactivate CFTR.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials.

We obtained human cDNAs from CLONTECH, β-agarase from New England Biolabs, the pCRII and pCR3-Uni vectors from InVitrogen, Pfu DNA polymerase from Stratagene, and Taq DNA polymerase from Boehringer Mannheim. Oligonucleotides were prepared on an automated Applied Biosystems synthesizer at the University of Iowa DNA Core Facility, Genosys (The Woodlands, TX), or GIBCO/BRL. DNAs were sequenced on an Applied Biosystems automated sequencer using fluorescent dye terminators. The catalytic subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) was from Promega; [γ-32P]ATP was from Du Pont/New England Nuclear; PP2A was from Calbiochem; and 8-(4-chlorophenylthio)-cAMP (cpt-cAMP) and okadaic acid were from Sigma. The activity of okadaic acid is shown in Fig. 3C.

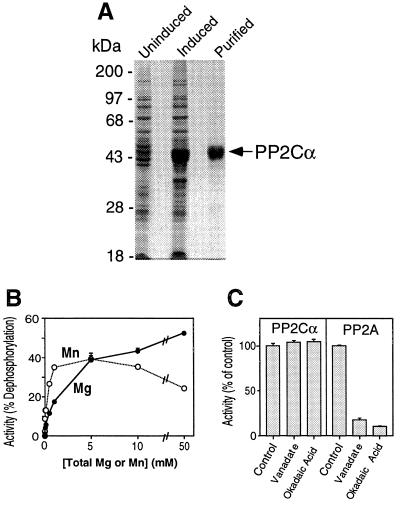

Figure 3.

Expression, purification, and properties of recombinant PP2Cα. (A) Coomassie blue-stained SDS/10% polyacrylamide gel showing proteins in uninduced and induced bacteria and PP2Cα purified by nickel-affinity chromatography. (B) Effects of Mg2+ or Mn2+ on phosphatase activity. Activity was measured with casein as the substrate under standard assay conditions except the total concentration of Mg2+ or Mn2+ was buffered with sodium citrate. Data are mean ± SEM of triplicate determinations. (C) Properties of PP2Cα activity. Phosphatase activity of PP2Cα and PP2A toward casein was measured under standard assay conditions in the absence and presence of 100 μM sodium orthovanadate or 10 μM okadaic acid. The incubation time and enzyme concentration were chosen to give incomplete dephosphorylation of casein in the absence of inhibitor; in the control samples, PP2A dephosphorylated casein 36%, and PP2Cα dephosphorylated it 55%. Data are mean ± SEM of triplicate determinations.

Cell Culture and Analysis of Transepithelial Current.

Human airway epithelial cells were isolated and grown on collagen-coated permeable filter supports (Millicell, Millipore) at the air–liquid interface by using methods developed by Yamaya and co-workers (17, 18). T84 cells were grown on permeable filter supports as described (19). Airway and T84 monolayers were mounted in modified Ussing chambers (Jim’s Instruments, Iowa City, IA). The basolateral membrane was treated with 100 μg/ml Staphylococcus aureus α-toxin, which permeabilizes the basolateral membrane to small molecules without altering the integrity or responsiveness of cAMP-regulated channels in the apical membrane (20). For our studies, α-toxin treatment facilitates the entry and washout of cAMP and okadaic acid. Apical membranes were bathed in (mM) 135 sodium aspartate, 5 Hepes, 1.2 MgCl2, 1.2 CaCl2, 2.4 K2HPO4, 0.6 KH2PO4, 10 dextrose (pH 7.40 with NaOH) (total apical [Cl−], 5 mM). Basolateral membranes were bathed in (mM) 135 NaCl, 5 Hepes, 1.2 MgCl2, 1.2 CaCl2, 2.4 K2HPO4, 0.6 KH2PO4, 10 dextrose, (pH 7.40 with NaOH) (total basolateral [Cl−], 140 mM). Thus there was a large Cl− concentration gradient across the epithelium, and transepithelial Cl− current was measured with the voltage clamped to 0 mV. Flow of Cl− current from the basolateral to the apical solution is shown as an upward current deflection. The solutions were maintained at 37°C and bubbled with O2.

Reverse Transcriptase (RT)-PCR.

RNA was isolated from monolayers of human airway and T84 epithelia by using guanidine thiocyanate (21). RNA was reverse transcribed using the GeneAmp PCR reagents (Perkin–Elmer), Moloney murine leukemia virus RT, and a PP2Cα gene-specific primer. As a negative control, RT was omitted from the reaction. PP2Cα was amplified by using two additional gene-specific primers, and the products were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis.

Cloning, Expression, and Purification of Human Lung PP2Cα.

The complete coding sequence of PP2Cα was amplified from human lung cDNA with Pfu DNA polymerase and primers designed to amplify the full coding sequence (GenBank accession no. S87759) (22). PCR products were fully sequenced from both strands. The sequence of human lung PP2Cα was identical to the published sequence of PP2Cα from human teratocarcinoma cells (22). To prepare PP2Cα DNA for protein expression in bacteria, the DNA was reamplified to incorporate terminal restriction sites. The sense primer included a start codon (boldface) within an NdeI site (underlined), and nucleotides encoding six histidines; the sense primer sequence was CATATGGGACATCATCATCATCATCATGCATTTTTAGACAAGCCAAA. The antisense primer included a stop codon (boldface) and an XbaI site (underlined); its sequence was TCTAGAGAATTACCACATATCATCTGTTGATGT. Thermal cycling was done using Pfu DNA polymerase and a program of one cycle at 94°C for 2 min; 30 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 50°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 3.5 min; with a final incubation at 72°C for 15 min. Taq DNA polymerase was added for 10 min at 72°C to incorporate terminal adenosine residues. PCR products were gel-purified and cloned into the pCRII vector. The PP2Cα sequence was excised from the pCRII vector as a NdeI/XbaI fragment and was ligated into the compatible sites of the pCW vector (23). This vector has been successfully used for the expression of several serine/threonine phosphatases (24–28). Escherichia coli strain DH5α was transformed with pCW-PP2Cα. Cells were grown at 37°C in Luria–Bertani broth with 1 mM MnCl2 until an OD600 of 0.5–0.6 was obtained, induced with 0.25 mM β-d-thiogalactopyranoside, then grown for 20 hr at 28°C. Cells were harvested and resuspended in 20 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.9/500 mM NaCl and lysed by sonication. PP2Cα was purified by nickel affinity chromatography (Novagen). The yield of PP2Cα was approximately 600 μg per liter of culture. Protein concentrations were determined with the Bio-Rad protein assay, using bovine serum albumin as the standard.

Preparation of CFTR and R1.

CFTR was expressed in HeLa cells and immunoprecipitated as described previously (29, 30). For R1, we amplified cDNA encoding amino acids 645–834 of CFTR by using PCR; this region of the R domain contains the major regulatory phosphorylation sites of CFTR. A similar polypeptide has proven useful for studies of CFTR phosphorylation (5). PCR products were purified from agarose gels and cloned into the pCRII vector as described above. The cDNA was isolated as a NcoI/BamHI fragment and cloned into the pET21d bacterial expression vector, which provides six histidine residues at the carboxyl terminus of the expressed protein. R1 was expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3)pLysS. Cells were grown and induced as described above for PP2Cα, and R1 was purified by nickel-affinity chromatography (Novagen).

Phosphatase Assays.

To prepare substrates for the phosphatase assays, CFTR, R1, and casein were phosphorylated for 60 min at 30°C in a 100-μl reaction volume containing 100 nM PKA, 50 mM potassium phosphate at pH 6.8, 20 mM MgCl2, and 0.1 mM [γ-32P]ATP at 20 Ci/mmol (1 Ci = 37 GBq). Bovine serum albumin was added at 0.1 mg/ml as a carrier protein, and samples were dialyzed at 4°C against 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.5/5 mM dithiothreitol, and 2 μg/ml each of leupeptin, pepstatin, and aprotinin to remove unincorporated [32P]ATP. Incorporated radioactivity was determined by SDS/PAGE and by measuring Cerenkov radiation. The standard dephosphorylation reaction mixture (50 μl) contained 20 mM Hepes at pH 7.5, 1 mM MgCl2, 2 mM MnCl2, 5 mM dithiothreitol, 10 μg/ml bovine serum albumin, and 32P-labeled substrate. For some experiments, 0.1–1.0 mM sodium citrate was used to buffer the Mg2+ and Mn2+ concentrations (31). Reactions were started by the addition of phosphatase. After incubation for 30 min at 37°C, reactions were terminated with 50 μl of cold 20% trichloroacetic acid and filtered by using a Multiscreen apparatus (Millipore). Released 32Pi in the filtrate was determined by measuring Cerenkov radiation. One unit of activity is that amount of enzyme that dephosphorylates 1 nmol of substrate per min in the standard assay. The specific activity of the purified PP2Cα was 1 unit⋅mg−1, with 50 μM casein as the substrate. Unless otherwise specified, assay mixtures contained 0.3 milliunits of PP2Cα.

Patch-Clamp Analysis.

The methods used for patch-clamp recording were similar to those previously described (32). We transiently expressed CFTR in HeLa cells using the vaccinia virus/T7 hybrid expression system described previously (8). The excised, inside-out configuration was used in all experiments. Cells and bath were maintained at 34–36°C by a temperature-controlled microscope stage (Brook Industries, Lake Villa, IL). Pipette resistance was 2–6 MΩ and seal resistance was 2–25 GΩ. The pipette (external) solution contained (mM): 140 N-methyl-d-glucamine, 2 MgCl2, 5 CaCl2, 100 l-aspartic acid, and 10 Hepes (pH 7.3 with HCl) (Cl− concentration, 50 mM). The bath (internal) solution contained (mM): 140 N-methyl-d-glucamine, 3 MgCl2, 1 cesium EGTA, and 10 Hepes (pH 7.3 with HCl) (Cl− concentration, 140 mM). The estimated free Ca2+ concentration in the internal solution was <10 nM. Additions to the bath solution are indicated for individual experiments. An Axopatch 200A amplifier (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA) was used for voltage-clamping and current amplification. The pClamp 6.0.3 software package (Axon Instruments) was used for data acquisition and analysis. Voltage was referenced to the external surface of the membrane patch: a depolarizing voltage is positive. Membrane voltage was held at −40 mV. Data points during time course experiments are mean current values during 2-s sweeps. Average current for an intervention were determined as the average of at least the last 1 min of that intervention.

Analysis of CFTR and PP2C Expressed in Fischer Rat Thyroid (FRT) cells.

FRT cells were grown on permeable supports as described (33). PP2Cα and β-galactosidase cDNAs were inserted into the pCR3-Uni vector, and CFTR was inserted into the pMT3 vector. Four days after seeding, FRT epithelia were transfected using the cationic lipid 1,2-dimyristyloxypropyl-N,N-dimethyl-N-hydroxyethylammonium bromide/dioleoyl phosphatidylethanolamine (DMRIE/DOPE; 50 μg per monolayer) in OptiMEM (GIBCO/BRL) with pMT3 plasmids encoding CFTR (5 μg per monolayer) alone or plus pCR3-Uni vector encoding PP2Cα or β-galactosidase (5 μg per monolayer). Six hours after transfection, the DNA/lipid-containing medium was removed and replaced with Coon’s modified Ham’s F-12 medium (Sigma) supplemented with 5% fetal calf serum (Sigma), 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin at 37°C. Six days after transfection, FRT epithelia were mounted in modified Ussing chambers. Transepithelial voltage was clamped at 0 mV, and a transepithelial Cl− concentration gradient (same bathing solutions as for airway epithelia and T84 cell studies: apical [Cl−], 5 mM; basolateral [Cl−], 140 mM) was imposed to measure current through CFTR Cl− channels. The time constants (τ) for inactivation were determined by using SigmaPlot (Jandel Scientific, San Rafael, CA).

RESULTS

Inactivation of CFTR in Epithelia.

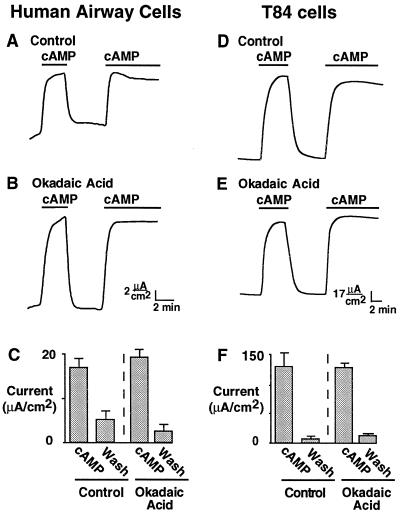

We studied primary cultures of human airway epithelia and T84 human colonic epithelia, in which cAMP agonists activate CFTR in the apical membrane (19, 34–36). To begin to identify which phosphatases regulate CFTR in epithelia, we examined the effect of okadaic acid, a cell-permeant inhibitor of PP1 and PP2A (37). Okadaic acid is effective in a variety of cell types (38), including mammalian epithelial cells from airway (39, 40) and intestine (41). Fig. 1A shows that addition of cAMP increased Cl− current in human airway epithelia permeabilized with α-toxin, as described previously (20). On removal of cAMP, the Cl− current promptly returned to baseline levels. This decline in current was due to dephosphorylation, because readdition of cAMP reactivated the channels. If PP1 or PP2A were primarily responsible for inactivation, we would expect that treating the epithelia with okadaic acid would either prevent or slow inactivation. Fig. 1B shows that okadaic acid did not prevent inactivation when cAMP was removed. Moreover, the rate at which current decreased after removal of cAMP was similar in the absence (0.48 ± 0.06 μA⋅cm−2⋅sec−1) and presence (0.47 ± 0.04 μA⋅cm−2⋅sec−1, P = 0.86) of okadaic acid. We obtained similar results with permeabilized T84 human colonic epithelial monolayers: okadaic acid failed to prevent channel inactivation (Fig. 1 D vs. E), and the rate of current decrease after cAMP removal was similar in the absence (0.86 ± 0.27 μA⋅cm−2⋅sec−1) and presence (1.06 ± 0.14 μA⋅cm−2⋅sec−1, P = 0.56) of okadaic acid. Fig. 1 C and F shows the results from several experiments: the amount of current activated by cAMP agonists was not different in control cells and in cells treated with okadaic acid. These studies suggest that the primary phosphatases that regulate CFTR in human airway and T84 intestinal epithelia are insensitive to okadaic acid, and thus are probably not PP1 or PP2A.

Figure 1.

Effect of okadaic acid on CFTR Cl− current. Primary cultures of human airway epithelia (Left) or T84 cells (Right) were grown on permeable supports; apical membrane current was recorded after the basolateral membrane was permeabilized with S. aureus α-toxin. Apical membrane Cl− current was activated by 100 μM cAMP during time indicated by the bars, in the absence (A and D) or in the continuous presence (B and E) of 10 μM okadaic acid. For experiments with okadaic acid, permeabilized monolayers were preincubated with the drug for 30 min. C and F show mean ± SEM of Cl− current in the presence of cAMP and after its removal; n = 4. “Wash” refers to the period after removal of cAMP. Currents were determined as the average of at least the last 1 min of the intervention.

We used FK506, a cell-permeant PP2B inhibitor (15), to ask whether this phosphatase regulates CFTR. In human airway epithelia, 1 μM FK506 did not alter the amount of current activated by cAMP agonists (P = 0.147) or the current inactivation rate when cAMP was removed (P = 0.108). Similarly, in T84 epithelia, 1 μM FK506 did not alter the amount of current activated by cAMP agonists (P = 0.506) or the current inactivation rate when cAMP was removed (P = 0.150). Moreover, previous studies indicated that PP2B added directly to CFTR in excised patches did not decrease activity (6). An alternative candidate for regulating CFTR is PP2C, a widely expressed protein phosphatase that is resistant to okadaic acid and FK506.

PP2Cα Is Expressed in Human Epithelial Cells.

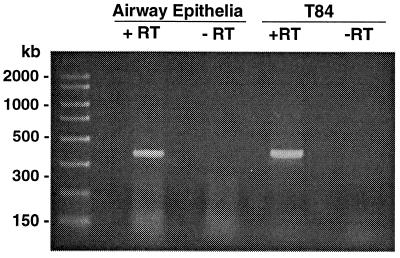

For PP2C to regulate CFTR, it must be present in epithelia that express CFTR. To learn whether PP2Cα transcripts were present in human epithelial cells, we reverse transcribed RNA from both airway and T84 epithelia, using PP2Cα-specific primers, then performed PCR with two additional gene-specific primers. We found a single PCR product of the size expected for PP2Cα with both airway and T84 cells (Fig. 2). These data indicate that PP2Cα is expressed in these epithelia. We do not know the amount of PP2Cα protein in epithelial cells. However, very low levels of PP2C could be sufficient to regulate CFTR because CFTR is present in very low levels in epithelia, because PP2C is catalytic, and because PP2C could be localized near CFTR.

Figure 2.

Products of RT-PCR of PP2Cα from human airway and T84 cells. RNA was reverse transcribed from mRNA by using a PP2Cα-specific primer, then amplified with two additional PP2Cα-specific primers. The presence and absence of RT is indicated.

Expression and Purification of PP2Cα.

We cloned the full coding sequence of PP2Cα from human lung cDNA, expressed it in bacteria, and purified it by metal chelate chromatography. Fig. 3A shows that induced bacteria expressed a protein of approximately 43 kDa, the expected size for the PP2Cα construct. A faster-migrating protein was also induced; this was likely a fragment of PP2Cα that lacked the amino-terminal His6 because of initiation from an internal methionine. Like native PP2C, the activity of recombinant PP2Cα required Mg2+ or Mn2+. In addition, it was insensitive to vanadate and okadaic acid (Fig. 3C). As a positive control for the effects of these inhibitors, we found that they inhibited PP2A (Fig. 3C). We found that recombinant PP2Cα had a broad pH optimum between 7.0 and 9.0 (data not shown), similar to native PP2C. These results indicate that recombinant PP2Cα has the enzymatic properties of native PP2C.

Dephosphorylation of CFTR by PP2Cα.

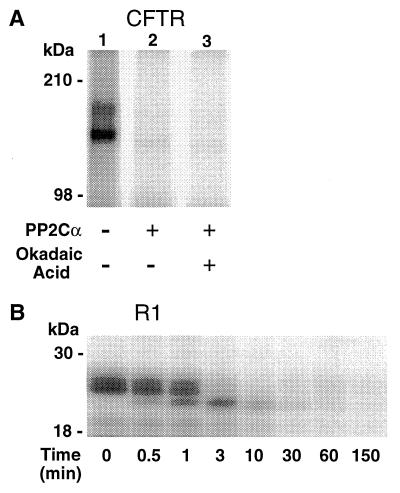

Fig. 4A shows that PP2Cα dephosphorylated CFTR that had been phosphorylated by PKA in vitro. Dephosphorylation was not inhibited by okadaic acid. PP2Cα also dephosphorylated R1, a recombinant R domain peptide (Fig. 4B). Dephosphorylation was accompanied by a progressive time-dependent change in the mobility of R1 on SDS/PAGE; at least three phosphorylated R1 bands were apparent, reflecting dephosphorylation of distinct phosphoserine residues (5). These results suggest that the phosphorylation sites that regulate CFTR were dephosphorylated by PP2Cα.

Figure 4.

PP2Cα dephosphorylation of CFTR and an R domain peptide in vitro. Substrates were phosphorylated with PKA and [γ-32P]ATP as described in the text. (A) CFTR was incubated without PP2Cα (lane 1), with PP2Cα (lane 2), or with PP2Cα and 10 μM okadaic acid (lane 3). In lane 1, the two glycosylated forms of CFTR are apparent. (B) R1 was incubated with PP2Cα for the time indicated. Samples were analyzed by SDS/PAGE and autoradiography.

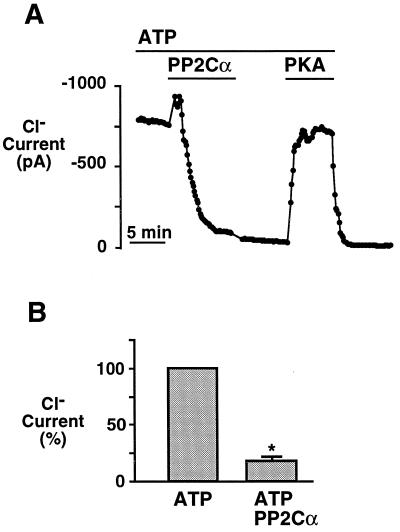

Inactivation of CFTR Cl− Channels by PP2Cα.

The ability of PP2Cα to dephosphorylate CFTR suggested that it would inactivate CFTR Cl− channels in excised membrane patches. Fig. 5A shows Cl− current from a patch of membrane containing multiple CFTR Cl− channels that had been activated with PKA and ATP. On addition of PP2Cα, the channels inactivated. In these experiments, we used 0.1 unit of PP2Cα per ml, in comparison to our previous studies of PP2A, in which we used 4.3 units of PP2A per ml. When PP2Cα was removed, the current did not increase, suggesting that the inhibition did not result from a nonspecific effect of PP2Cα. Upon readdition of PKA, current increased, indicating that inactivation occurred through dephosphorylation. When PKA and ATP were removed, the CFTR Cl− current decreased, consistent with the ATP requirement for channel activity. Addition of the phosphatase buffer alone had no effect (n = 4, not shown). Fig. 5B shows results from several experiments, indicating that PP2Cα significantly reduced CFTR Cl− current. We also applied PP2C for 7 min in the absence of ATP; when PP2C was removed and ATP was readded only 16% ± 9% (n = 3, not shown) of CFTR current remained. This amount of current is not different from that remaining after application of PP2C for 7 min in the presence of ATP (Fig. 5B). These data suggest that PP2Cα can inactivate CFTR in the presence or absence of ATP.

Figure 5.

Effect of PP2Cα on CFTR Cl− current in excised membrane patches. (A) Time course of current in an excised, inside-out membrane patch from HeLa cells transiently expressing CFTR. Current had been activated by PKA and ATP. ATP (1 mM), PKA (75 nM), and PP2Cα (0.1 unit/ml) were present in the cytosolic solution during times indicated by bars. (B) Average current in the absence or presence of PP2Cα, determined as the average of at least the last 1 min of that intervention (n = 5). Asterisk indicates a significant difference in current in the absence and presence of PP2Cα (P < 0.00001).

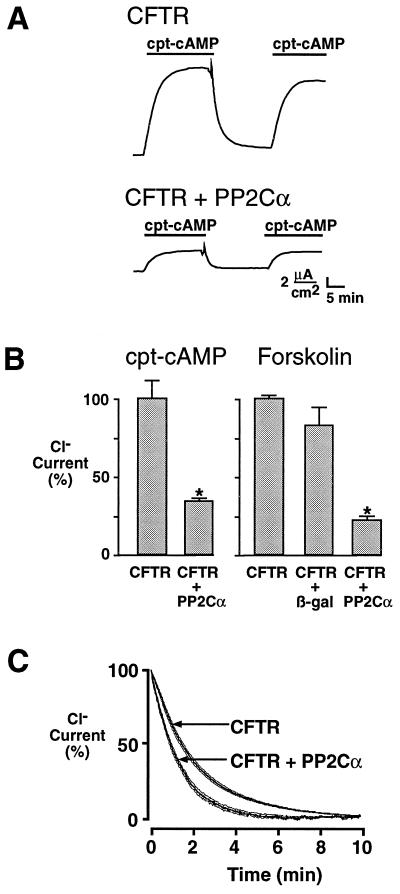

PP2Cα Regulates CFTR in an Epithelial Monolayer.

Because cellular factors that modulate phosphatase activity may be absent from excised patches, we asked whether PP2Cα could regulate CFTR expressed in an epithelium. We used polarized FRT epithelial monolayers; these cells do not express endogenous cAMP-regulated Cl− channels in their apical membrane, and they are easily transfected with CFTR cDNA (33, 42). CFTR-transfected FRT epithelia expressed Cl− current that was activated by a submaximal stimulus (500 μM cpt-cAMP, 14.5 ± 2.8 μA/cm2, n = 14) or a maximal stimulus (10 μM forskolin, 53.2 ± 7.7 μA/cm2, n = 13). When we removed the cAMP agonists, the current decreased, presumably due to inactivation of CFTR by endogenous phosphatases. The inactivation of CFTR was not prevented or slowed by 10 μM okadaic acid (not shown). However, coexpression of PP2Cα reduced CFTR Cl− currents with both maximal and submaximal stimulation (Fig. 6 A and B). Coexpression of a control plasmid encoding β-galactosidase had no significant effect on Cl− current. These results suggest that coexpression of PP2Cα shifts the balance between kinase activation and phosphatase inactivation, resulting in less total Cl− current. We also analyzed the effects of PP2Cα on the rate of channel inactivation, and we found that coexpression of PP2Cα caused CFTR to inactivate faster (Fig. 6C). The time constant (τ) for inactivation was significantly decreased from a control value of 125 ± 4 sec to 76 ± 5 sec in the presence of PP2Cα (P < 0.00001).

Figure 6.

Effect of coexpressing PP2Cα and CFTR on Cl− current in FRT epithelia. (A) Current activated with 500 μM cpt-cAMP in FRT epithelia expressing CFTR, or CFTR plus PP2Cα. (B) Current activated by 500 μM cpt-cAMP or 10 μM forskolin in FRT expressing CFTR, CFTR plus PP2Cα, or CFTR plus β-galactosidase (control) expressed as percent of current activated in FRT expressing only CFTR. Asterisk indicates a significant difference in current compared with FRT expressing CFTR alone (P < 0.00001, n = 8). (C) Time course of current inactivation. Current was recorded as a percent of current measured 1 min prior to removal of 500 μM cpt-cAMP (time zero). Data are mean (thick line) and SEM (thin lines), n = 8.

DISCUSSION

Previous work has shown that PKA phosphorylates CFTR on multiple serines in the R domain, and this activates the channel (1–10). Here we show that PP2Cα dephosphorylated CFTR and reversed the effects of PKA. Dephosphorylation of multiple serines was most readily apparent in studies of R1, where several distinct forms of the peptide were observed during dephosphorylation. Consistent with dephosphorylation, PP2Cα inactivated CFTR in cell-free patches of membrane and reduced cAMP-stimulated Cl− current in intact cells.

These results combined with earlier work suggest that CFTR may be regulated by more than one phosphatase, and this regulation depends on the cell type. In the human sweat duct, okadaic acid-sensitive phosphatases regulate CFTR (16). In guinea pig cardiac myocytes, CFTR is regulated both by an okadaic acid-sensitive phosphatase and by an okadaic acid-insensitive phosphatase (7, 9). Similarly, in insect cells expressing recombinant CFTR, channel activity is regulated by calyculin A-sensitive and calyculin A-insensitive phosphatases (43). In human pancreatic duct cells, an okadaic acid-insensitive phosphatase appears to inactivate CFTR (44). In Chinese hamster ovary cells, recombinant CFTR is inactivated by a phosphatase that resembles alkaline phosphatase (2, 44). The effects of okadaic acid in human sweat duct, guinea pig cardiac myocytes, and insect cells suggest that PP1 or PP2A is responsible; the previous demonstration that PP2A, but not PP1, could dephosphorylate and inactivate CFTR (6) suggests that PP2A may play a role in those cells. Our studies do not exclude a role for PP2A in regulating CFTR in human airway and T84 epithelia. However, they do suggest that an okadaic acid-insensitive phosphatase is an important regulator of CFTR in these epithelial cells.

Although both PP2A (6, 45) and PP2C can dephosphorylate and inactivate CFTR in vitro and in cell-free membrane patches, the relative importance of PP2A and PP2C in regulating CFTR appears to differ among tissues. This may reflect differential localization or regulation of the phosphatases in different cell types. For example, PP2A has multiple regulatory subunits that vary among tissues and modulate its activity toward specific substrates (46, 47). Such regulation may control its activity toward CFTR in different cell types. In contrast, there is little knowledge of how the activity of PP2C is governed. Identification of the molecular basis for PP2C regulation may help us understand better how CFTR activity is controlled.

At the present time there are no known specific inhibitors of PP2C. The development of such inhibitors would be an important advance and could provide additional insight into the role of this phosphatase in regulating CFTR. Two isoforms of PP2C, α and β, have been purified from a variety of mammalian tissues; these proteins are similar enzymatically (48) and have approximately 70% sequence identity (22, 49, 50). The availability of isoform-specific inhibitors would help determine which PP2C isoform regulates CFTR in vivo. It has also been proposed that phosphatase inhibitors might be of value as a therapeutic intervention in cystic fibrosis (51). Our data suggest that in the airway, an important site of cystic fibrosis pathogenesis, PP2C may be an important phosphatase to target.

Acknowledgments

We thank Norma Hillerts, Anthony Thompson, Philip Karp, Pary Weber, Theresa Mayhew, and our other colleagues for advice and assistance. We are grateful to Dr. F. W. Dahlquist for the pCW plasmid. T84 RNA was generously provided by Dr. Margaret Price. We thank the University of Iowa Diabetes and Endocrinology Research Center DNA Core Facility (supported by National Institutes of Health grant DK25295) for oligonucleotide synthesis and sequencing. This work was supported by the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. M.J.W. is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the Proceedings Office.

Abbreviations: CFTR, cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator; PP, protein phosphatase; PKA, cAMP-dependent protein kinase (protein kinase A); cpt-cAMP, 8-(4-chlorophenylthio)-cAMP; RT, reverse transcriptase; FRT, Fischer rat thyroid.

References

- 1.Gregory R J, Cheng S H, Rich D P, Marshall J, Paul S, Hehir K, Ostedgaard L, Klinger K W, Welsh M J, Smith A E. Nature (London) 1990;347:382–386. doi: 10.1038/347382a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tabcharani J A, Chang X-B, Riordan J R, Hanrahan J W. Nature (London) 1991;352:628–631. doi: 10.1038/352628a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng S H, Rich D P, Marshall J, Gregory R J, Welsh M J, Smith A E. Cell. 1991;66:1027–1036. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90446-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohn J A, Nairn A C, Marino C R, Melhus O, Kole J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:2340–2344. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.6.2340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Picciotto M R, Cohn J A, Bertuzzi G, Greengard P, Nairn A C. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:12742–12752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berger H A, Travis S M, Welsh M J. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:2037–2047. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hwang T-C, Horie M, Gadsby D C. J Gen Physiol. 1993;101:629–650. doi: 10.1085/jgp.101.5.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rich D P, Berger H A, Cheng S H, Travis S M, Saxena M, Smith A E, Welsh M J. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:20259–20267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hwang T-C, Nagel G, Nairn A C, Gadsby D C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:4698–4702. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.11.4698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Townsend R R, Lipniunas P H, Tulk B M, Verkman A S. Protein Sci. 1996;5:1865–1873. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560050912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen P. Annu Rev Biochem. 1989;58:453–508. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.58.070189.002321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ballou L M, Fischer E H. In: The Enzymes. Boyer P D, Krebs E G, editors. Orlando, FL: Academic; 1986. pp. 311–361. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shenolikar S, Nairn A C. Adv Second Messenger Phosphoprotein Res. 1991;23:1–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shenolikar S. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1994;10:55–86. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.10.110194.000415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu J, Farmer J D, Jr, Lane W S, Friedman J, Weissman I, Schreiber S L. Cell. 1991;66:807–815. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90124-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reddy M M, Quinton P M. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:C474–C480. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.270.2.C474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamaya M, Finkbeiner W E, Chun S Y, Widdicombe J H. Am J Physiol. 1992;262:L713–L724. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1992.262.6.L713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zabner J, Zeiher B G, Friedman E, Welsh M J. J Virol. 1996;70:6994–7003. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.10.6994-7003.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anderson M P, Welsh M J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:6003–6007. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.14.6003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ostedgaard L S, Shasby D M, Welsh M J. Am J Physiol. 1992;263:L104–L112. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1992.263.1.L104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. New York: Greene and Wiley–Interscience; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mann D J, Campbell D G, McGowan C H, Cohen P T W. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1130:100–104. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(92)90471-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gegner J A, Dahlquist F W. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:750–754. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.3.750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang Z, Bai G, Deans-Zirattu S, Browner M F, Lee E Y C. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:1484–1490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alessi D R, Street A J, Cohen P, Cohen P T W. Eur J Biochem. 1993;213:1055–1066. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb17853.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Becker W, Kentrup H, Klumpp S, Schultz J E, Joost H G. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:22586–22592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Armstrong C G, Mann D J, Berndt N, Cohen P T W. J Cell Sci. 1995;108:3367–3375. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.11.3367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davies S P, Helps N R, Cohen P T W, Hardie D G. FEBS Lett. 1995;377:421–425. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01368-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Denning G M, Ostedgaard L S, Cheng S H, Smith A E, Welsh M J. J Clin Invest. 1992;89:339–349. doi: 10.1172/JCI115582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ostedgaard L S, Welsh M J. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:26142–26149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brooks S P J, Storey K B. Anal Biochem. 1992;201:119–126. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(92)90183-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hamill O P, Marty A, Neher E, Sakmann B, Sigworth F J. Pflügers Arch. 1981;391:85–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00656997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sheppard D N, Carson M R, Ostedgaard L S, Denning G M, Welsh M J. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:L405–L413. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1994.266.4.L405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Widdicombe J H, Welsh M J, Finkbeiner W E. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:6167–6171. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.18.6167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mandel K G, Dharmsathaphorn K, McRoberts J A. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:704–712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Frizzell R A. News Physiol Sci. 1993;8:117–120. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haystead T A J, Sim A T R, Carling D, Honnor R C, Tsukitani Y, Cohen P, Hardie D G. Nature (London) 1989;337:78–81. doi: 10.1038/337078a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hardie D G, Haystead T A J, Sim A T R. Methods Enzymol. 1991;201:469–476. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)01042-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liedtke C M. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:L414–L423. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1995.268.3.L414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liedtke C M, Thomas L. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:C338–C346. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.271.1.C338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mathur S N, Born E, Bishop W P, Field F J. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1993;1168:130–143. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(93)90117-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sheppard D N, Rich D P, Ostedgaard L S, Gregory R J, Smith A E, Welsh M J. Nature (London) 1993;362:160–164. doi: 10.1038/362160a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang I C-H, Cheng T-H, Wang F, Price E M, Hwang T-C. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:C142–C155. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.272.1.C142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Becq F, Fanjul M, Merten M, Figarella C, Hollande E, Gola M. FEBS Lett. 1993;327:337–342. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81016-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li C, Ramjeesingh M, Wang W, Garami E, Hewryk M, Lee D, Rommens J M, Galley K, Bear C E. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:28463–28468. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.45.28463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kamibayashi C, Mumby M C. Adv Prot Phosphatases. 1995;9:195–210. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhao Y, Boguslawski G, Zitomer R S, DePaoli-Roach A A. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:8256–8262. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.13.8256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McGowan C H, Cohen P. Eur J Biochem. 1987;166:713–722. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1987.tb13570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tamura S, Lynch K R, Larner J, Fox J, Yasui A, Kikuchi K, Suzuki Y, Tsuiki S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:1796–1800. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.6.1796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wenk J, Trompeter H-I, Pettrich K-G, Cohen P T W, Campbell D G, Mieskes G. FEBS Lett. 1992;297:135–138. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80344-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Collins F S. Science. 1992;256:774–779. doi: 10.1126/science.1375392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]