Abstract

Background

Internists commonly perform invasive procedures, but serious deficiencies exist in procedure training during residency.

Objective

Evaluate a comprehensive, inpatient procedure service rotation (MPS) to improve Internal Medicine residents’ comfort and self-perceived knowledge in performing lumbar puncture, abdominal paracentesis, thoracentesis, arthrocentesis, and central venous catheterization (CVC).

Design

The MPS comprised 1 faculty physician and 1–3 residents rotating for 2 weeks. It incorporated lectures, a textbook, instructional videos, supervised practice on mannequins, and inpatient procedures directly supervised by the faculty physician. We measured MPS impact using pre- and post-MPS rotation surveys, and surveyed all residents at academic year-end.

Measurements and Main Results

Thirty-nine categorical Internal Medicine residents completed the required rotation and surveys over the 2004–2005 academic year, performing 325 procedures. Post-MPS, the percentage of residents reporting comfort performing procedures rose 15–36% (p < .05 except for arthrocentesis, and CVC via internal jugular and femoral veins). The fraction desiring more training fell 26–51% (all p < .05). After the MPS rotation, self-rated knowledge increased in all surveyed aspects of the procedures. The year-end survey showed that improvements persisted. Comfort at year-end, for all procedures except abdominal paracentesis, was significantly higher among residents who rotated through the MPS than among those who had not. Self-reported compliance with recommended antiseptic measures was 75% for residents who completed the MPS, and 28% for those who had not (p < 0.001).

Conclusions

A comprehensive procedure service rotation of 2 weeks duration substantially improved residents’ comfort and self-perceived knowledge in performing invasive procedures. These benefits persisted at least to the end of the academic year.

KEY WORDS: medical education, residency training

INTRODUCTION

Training in invasive procedures, such as lumbar puncture (LP), thoracentesis (TC), paracentesis (PC), arthrocentesis (AC), and central venous catheterization (CVC), has traditionally been a vital part of Internal Medicine education.1 As recent data show that General Internists in practice still commonly perform such procedures,2 it is important that training render residents competent and comfortable in doing them; however, this often does not occur.3–7 Many residency directors judge that many Internal Medicine residents fail to master routine procedures,8 and Internal Medicine residents often feel uncomfortable with their procedural skills.5,7

A modest literature addresses methods of teaching physicians in training to perform procedures.6,7,9–15 Three main interventions are described: (1) didactic teaching, (2) supervised practice on mechanical models or cadavers, and (3) performing procedures on patients under direct supervision by experienced faculty. No prior published study used more than 2 of these educational interventions, and most applied the interventions for quite brief intervals.

We created a comprehensive medical procedure service rotation of 2 weeks duration, combining didactic teaching, practice on mechanical models, and procedures supervised by faculty. We hypothesized that rotating through this service would improve residents’ comfort, and self-perceived knowledge in performing invasive bedside procedures.

NEEDS ASSESSMENT

As a prelude to revising procedure training in our residency program, toward the end of the residency year we anonymously surveyed 153 Internal Medicine residents in 4 programs in the Midwestern United States regarding invasive procedures including lumbar puncture (LP), abdominal paracentesis (PC), thoracentesis (TC), and central venous catheterization (CVC) via subclavian, internal jugular, and femoral routes. We queried the number of procedures performed, frequency of supervision, comfort level, and use of sterile technique. For CVC insertion, we asked about full sterile barrier precautions: “Have you been taught that the current recommendations on sterile technique for bedside insertion of CVCs include use of all of: mask, hat, sterile gloves, sterile gown, a full-size sterile sheet, and chlorhexadine skin prep?” With respect to documentation, we asked how often they included notations in their procedure notes about consent, indication for procedure, equipment used, technique, details of anesthesia, number of needle passes, and complications.

By the end of residency, the 52 postgraduate year (PGY) 3 residents reported performing a median of 7.5 procedures each for PC, TC, and LP, and 35 for CVCs. Supervision by faculty or subspecialty fellows was limited; 77% of all residents reported that such supervision occurred rarely (≤25% of attempts) for CVC. This fraction was 60% for LP and PC, and 33% for TC. Although 56–92% of PGY3s in the final months of their residencies reported feeling comfortable performing the various procedures, 31–52% of them wanted more training in them. Only 52% of residents reported knowing the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommendations for full barrier precautions when inserting CVCs.16 When inserting CVCs, only 55% reported that they always or almost always used full barrier precautions, with no significant difference between the residency years.

Twelve percent of residents did not routinely write procedure notes after successful procedures, and 39% did not routinely write them after unsuccessful procedures. Sixty-three percent almost or almost always included details of informed consent in their procedure notes, whereas 55% included indication, 32% included the number of needle passes, and 82% included complications.

Our findings regarding comfort level are similar to previous reports where 10–32% of residents were uncomfortable doing CVC, LP, PC, or TC, compared with 8–42% in our study.7,5 Prior studies found that most residents were uncomfortable performing these procedures even after doing 5 of each. Lack of supervision is reported to be the largest source of residents’ procedure discomfort,7 and supervision was rare in our study. The findings from this survey informed the design of our medical procedure service; we focused particularly on sterile technique, supervision, and medical documentation.

METHODS

Study data were collected prospectively in a 520-bed urban, county-owned, university-affiliated teaching hospital located in the Midwestern United States, between July 2004 and May 2005. Categorical PGY 2, 3, and 4 Internal Medicine (IM) and medicine-pediatrics residents participated in the study.

In July 2004, the inpatient medical procedure service (MPS) team began operating. It consisted of 1 faculty physician expert in performing bedside invasive medical procedures, either a Critical Care physician or a Hospitalist, and 1–3 residents who were PGY 2, 3, or 4. As part of the program’s core curriculum, the rotation lasted 2 weeks with all residents scheduled to rotate through it once during their training.

The MPS team performed nonemergent procedures (LP, PC, TC, AC, and CVC) during weekday afternoons for Internal Medicine inpatients, including in the intensive care wards. The departmental leadership and faculty agreed to giving the MPS the first option for such procedures. The MPS identified these procedures by visiting each primary team in the late morning, or by being paged by primary team residents.

Once called, the MPS team was responsible for the all aspects of the procedure, including informed consent, performing the procedure, handling the samples, and assessing any postprocedure imaging. An MPS resident was the primary operator during the procedure; if he/she was unable to successfully complete the procedure a different MPS resident or faculty physician completed it. The other MPS residents typically observed procedures for which they were not the operator. The faculty physician supervised all procedures, and provided immediate and postprocedure feedback to the residents.

Simultaneous with creation of the MPS, we used our computerized medical record program (EPIC, Epic Systems Corporation, Verona, WI, USA) to implement standardized procedure notes that minimized the need to type in free text by utilizing preformatted, drop-down lists. These procedure notes included all elements recommended by the faculty, hospital legal department, and Joint Commission on the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO). The MPS residents maintained a central log of all procedures performed by the MPS.

The MPS combined didactic teaching, practice on mechanical models, and faculty-supervised procedures. The MPS had a designated room equipped with a television/VCR, videotapes, procedure mannequins, and a computer with internet access. The didactic components were concentrated in the first week of the rotation. On each of the first 5 days the residents received a 60-minute lecture created by the MPS directors, viewed commercially available, instructional video recordings covering each procedure, and were taught how to use the procedure mannequins (Nasco, Modesto, CA, USA; Pacific Research Laboratories, Vashon, WA, USA). The first lecture discussed general aspects including informed consent, safety, infection control, and procedure documentation. The other lectures detailed each procedure including indications, contraindications, mechanical technique, antiinfection precautions, and complications. The faculty member would typically demonstrate the procedure on the mannequin and then observe the residents in its use until satisfied that they were correctly performing the maneuvers; no fixed number of supervised repetitions on the mannequins were mandated. Residents also were provided with an instructional reference book for bedside invasive procedures.17 After these educational activities, the team performed actual procedures as discussed. No formal assessment of residents’ knowledge was performed before performing supervised procedures on patients.

All MPS activities involving the faculty physician took place in the afternoons; in the mornings the MPS residents were strongly urged to practice repeatedly on the mannequins, and to review the lectures, video recordings, and textbook. No fixed number of unsupervised repetitions on the mannequins were mandated. They also used the mornings to each prepare a weekly 15- to 30-minute oral presentation on procedure-related topics.

We assessed the impact of the MPS on residents using 3 surveys. To assess the immediate influence of the MPS, those who rotated through it completed preservice and postservice surveys. The pre-MPS survey was administered on the first day of the MPS rotation before teaching occurred; the post-MPS survey was administered on the final day of the rotation. Residents answered questions about their age, gender, year of training, and residency details. For each procedure, they reported their comfort on a 5-point Likert scale, and answered a Yes/No query about whether they want more training and education. Also using a 5-point scale, the trainees reported their self-perceived level of knowledge about the following aspects of invasive procedures: indications, complications, procedure notes, sterile technique, and insertion techniques. A separate question asked whether the resident knew the CDC guidelines about aseptic techniques for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections. The post-MPS survey also inquired about the value of each element of the rotation.

Toward the end of the 2004–05 academic year we anonymously surveyed all PGY 2, 3, and 4 residents to evaluate retention of comfort performing the procedures, and to compare comfort levels between residents who rotated through the MPS versus those who did not. Because this survey was anonymous, comparisons of responses from the post-MPS and year-end surveys were done using unpaired statistical tests. The year-end survey did not ask about arthrocentesis.

Residents were defined as being comfortable performing a procedure if they rated their comfort as a response of 4 (moderately comfortable) or 5 (very comfortable) on the 5-point scale. Continuous data were summarized using the median and interquartile range. Exact symmetry tests were used to compare the paired pre-MPS and post-MPS variables. Fisher’s exact tests were used for unpaired comparisons. P values ≤0.05 were considered significant. Statistical analysis was performed using Stata 9.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). The study protocol was approved by the hospital’s Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

Forty residents completed the MPS rotation between July 2004 and May 2005; 1 resident did not complete these surveys, leaving 39 for the pre-post-MPS survey comparison. Table 1 provides their characteristics. These 39 residents completed 325 supervised procedures while on the MPS, including 109 CVCs, 73 TC, 69 PC, 69 LP, and 5 AC. This represents an average of 8.3 procedures per resident over the 2-week rotation.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Residents Who Rotated Through the Medical Procedure Service and Completed the Surveys Before and After that Experience (n = 39)

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Residency type, n (%) | |

| Internal Medicine | 36 (92) |

| Medicine/Pediatrics | 3 (8) |

| Training Year, n (%) | |

| Postgraduate year 2 | 21 (54) |

| Postgraduate year 3 | 16 (41) |

| Postgraduate year 4 | 2 (5) |

| Male gender, n (%) | 28 (72) |

| Medical School, n (%) | |

| US | 15 (38) |

| International | 24 (62) |

| Age (years, mean ± SD) | 30.2 ± 3.6 |

| Prior medical experience after medical school, before current residency, n (%) | 18 (46) |

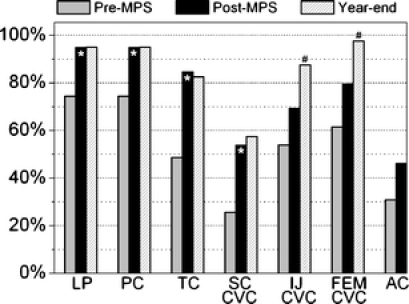

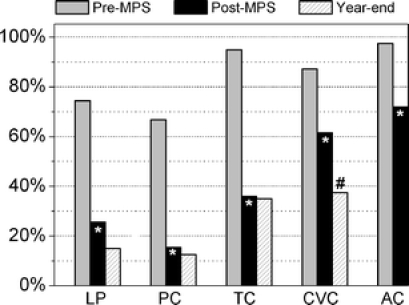

Before their MPS rotation, 26–74% of residents reported being comfortable performing the various procedures; this was lowest for subclavian CVC and AC, and highest for LP and PC (Fig. 1). After completing the MPS, this parameter rose by 15–36% (Fig. 1). The improvement was not statistically significant for AC, and was of borderline significance for CVC in the internal jugular and femoral veins (each p = .07). After rotating on the MPS, the percentage of residents who wanted additional training declined significantly for all procedures by 26–51% (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

Percentages of residents that completed the Medical Procedure Service rotation who reported being comfortable performing invasive procedures in 3 surveys. *p < .05 compared to Pre-MPS survey; #p < .05 compared to post-MPS survey. MPS medical procedure service, LP lumbar puncture, PC abdominal paracentesis, TC thoracentesis, SC CVC subclavian vein central venous catheterization, IJ CVC internal jugular vein central venous catheterization, FEM CVC femoral vein central venous catheterization, AC arthrocentesis.

Figure 2.

Percentages of residents that completed the Medical Procedure Service rotation who reported a desire for more education and training regarding invasive procedures in 3 surveys. *p < .05 compared to pre-MPS survey; #p < .05 compared to post-MPS survey. MPS medical procedure service, LP lumbar puncture, PC abdominal paracentesis, TC thoracentesis, CVC vein central venous catheterization, AC arthrocentesis.

Before the MPS rotation, residents had a high self-perceived knowledge about the elements of invasive procedures; the median was 4 on a 5-point scale for all aspects of procedures except insertion techniques where the median was 3. After the MPS rotation, median self-perceived knowledge increased to 5 for all aspects of procedures except insertion techniques where it increased to 4 (all p < 0.001). Before their MPS rotations, 69% of residents reported being taught the current CDC recommendations for preventing intravascular catheter-related infections during CVC placement,16 versus 100% after the MPS rotation (p < 0.001).

Residents rated all elements of the MPS as helpful in learning invasive procedures. Specifically, 95–97% of residents rated lectures, instructional videos, practicing on the mannequins, and direct supervision by the faculty physician as moderately or very helpful. Only 59% of residents rated the reference book as moderately or very helpful.

Fifty-eight of the 59 eligible residents completed the academic year-end survey, of whom 40 (69%) had rotated on the MPS. Among these 40 was the resident who had been excluded from the pre-post MPS survey comparison; the anonymous nature of the year-end surveys precluded us from identifying and excluding this individual from comparisons between the year-end and pre-MPS surveys. During a mean interval of 5 months between their MPS rotations and the year-end survey (IQR 2–7 months), the MPS-related gains in procedure comfort were maintained (Figs. 1 and 2). For all procedures assessed at year-end, comfort levels were similar or higher than at the end of the MPS rotation, with the same or fewer residents saying they desired more procedure education. To assess whether residents who had not experienced the MPS had “caught up” with the passage of time, we compared year-end responses of the subgroups which had versus had not experienced the MPS. There were no significant differences between the subgroups regarding PGY year, gender, medical school location (US vs international) and having medical experience after medical school but before the current residency. Except for paracentesis, comfort levels at year-end were significantly higher among residents who rotated through the MPS than among those who had not (Table 2). Similarly, MPS residents were significantly less likely to desire further training in all of the procedures. At year-end, residents who had not rotated on the MPS responded similarly to MPS residents before their MPS rotation.

Table 2.

Tabulation of Residents Who Reported Being Comfortable Doing Invasive Procedures, and Who Wanted More Training Doing Those Procedures Prior to the Medical Procedure Service (MPS) and at Academic Year-end

| Procedure | Academic year-end survey | Pre-MPS survey | p value* | p value† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Did not complete MPS (N = 18) n (%) | Completed MPS (N = 40) n (%) | (N = 39) n (%) | |||

| Comfortable doing procedure | |||||

| Lumbar puncture | 13 (72) | 38 (95) | 29 (75) | .03 | 1.00 |

| Paracentesis | 15 (83) | 38 (95) | 29 (75) | .17 | .52 |

| Thoracentesis | 9 (50) | 33 (83) | 19 (49) | .02 | 1.00 |

| Subclavian CVC | 5 (28) | 23 (58) | 10 (26) | .049 | 1.00 |

| Internal jugular CVC | 7 (39) | 35 (88) | 21 (54) | <.001 | .40 |

| Femoral CVC | 12 (67) | 39 (98) | 24 (62) | .003 | .78 |

| Want more training/education | |||||

| Lumbar puncture | 11 (61) | 6 (15) | 29 (74) | .001 | .36 |

| Paracentesis | 10 (56) | 5 (13) | 26 (67) | .001 | .56 |

| Thoracentesis | 16 (89) | 14 (35) | 37 (95) | <.001 | .58 |

| CVC | 16 (89) | 15 (38) | 34 (87) | <.001 | 1.00 |

*Comparison of those who did and did not complete the MPS at year-end

†Comparison of responses for residents who did not complete the MPS with pre-rotation responses of those who completed the MPS

At the year-end survey, 100% of residents in the MPS group reported being taught the current CDC guidelines to prevent intravascular catheter-related infections, compared with two thirds of the residents who did not rotate on the MPS (p<0.001). When asked about actual practice, 75% of residents who completed the MPS reported always or almost always using a full-size sterile sheet when performing CVC, versus 28% of those who had not completed the MPS (p < .001).

DISCUSSION

We developed and implemented a novel clinical rotation for Internal Medicine residents whose goal was to improve education and training in performing the invasive procedures frequently done by Internists. This intervention improved residents’ comfort and self-perceived knowledge related to procedures, with benefits maintained at least to the end of the academic year. The rotation also increased the self-reported utilization of recommended antiseptic precautions for inserting CVCs.

It is noteworthy that substantial improvements occurred despite residents performing a mean of only 8.3 procedures while on the MPS. Perhaps only a few procedures attempts are needed to improve a physician’s comfort; whereas 1 report suggested that this may be true,18 others have not.5,7 Also, the residents may have learned from observing their fellow MPS residents performing additional procedures. Or perhaps the opportunity afforded the MPS residents to practice extensively on the anatomically correct mannequins is the explanation. The MPS was designed as a half-day activity to allow the residents to spend considerable time over the 2 weeks practicing on the mannequins. However, we believe the observed improvements were a result of a combination of the lectures, instructional videos, practice on mannequins, and supervision of all aspects of this learning experience by expert faculty physicians. The finding that each of these MPS components was rated as moderately or very helpful by >95% of the residents supports this interpretation. As Wigton19 has suggested, the technical aspects of procedures are not difficult to learn, and the cognitive aspects of procedures are just as important. The structure of our MPS emphasized both aspects.

Indeed, it is the comprehensive, multifaceted nature of our procedure service that distinguishes it from prior interventions to improve procedure education. The MPS model is more akin to the personalized instruction that surgical residents receive in the operating room than it is to traditional classroom learning, or to the worrisome “learn one, do one, teach one” paradigm. Whereas some combined didactic education with practice on mannequins or cadavers,9–13,15 and others combined didactic education and direct faculty supervision,7,20 we are not aware of any prior studies that combined all these modalities.

In 3 studies assessing the value of 1- to 2-day workshops combining didactic teaching with practice on cadavers or mannequins, procedure knowledge increased by 15–20%.11,12,15 A 1-day didactic course on infection control increased residents’ use of full-size sterile sheets during CVC by 21%.6 Two studies evaluated direct supervision of invasive, bedside procedures by faculty. Although only a slightly higher fraction of Internal Medicine residents were comfortable performing invasive, inpatient procedures under direct faculty supervision (53% vs 46%, p = .13), such supervision was associated with a significantly higher odds ratio (OR) for comfort in a multivariable analysis (OR = 1.9, 95% CI, 1.1–3.4).7 Ramakrishna et al. evaluated the self-rated competency of PGY2 Internal Medicine residents who completed 10 hours of CVC experience in the cardiac catheterization laboratory directly supervised by cardiologists.14 Scored on a 5-point scale, the residents’ mean self-rated competency rose from 2.8 to 4.4 (p < 0.001); however, at the end of residency, self-rated competency did not differ between those who had, and had not, completed that experience (4.1 vs 3.7, p = 0.26).

Our study has 2 main limitations. First, it was a single center study, and although problems in procedure training are common,5,7 other studies confirming our results are indicated. Second, our outcome measures were subjective and secondary in nature. Few studies about procedure training have assessed the most relevant outcomes, procedure-related complication rates, and these have been limited by before versus after study design lacking a contemporaneous control group. A study that combined didactic education with practice on cadavers observed a significant 42% decline in the rate of CVC-related pneumothorax.10 A didactic intervention on infection control was associated with a 35% fall in the rate of CVC-related bloodstream infections.6 A small number of studies assessed the value of interventions to improve trainees’ procedure competency as rated by faculty observers.9,12,13

We have 2 additional comments about our findings. First, a lower desire for more training may not be desirable among either trainees or practicing physicians. In fact, we queried desire for more procedure training in the context of questions about comfort and experience levels. Thus, it seems likely that the respondents were considering their desire for more procedure training in terms of wanting more training to feel comfortable performing them. The strong inverse relationship observed between comfort and desire for more training supports this interpretation. Second, between the post-MPS and academic year-end surveys, residents’ comfort in performing CVCs by the internal jugular and femoral routes significantly rose (Fig. 1). Speculative explanations could include post-MPS consolidation of knowledge and experience, random statistical fluctuations, and others.

The cost of our MPS could be an obstacle to widespread implementation. The initial cost of purchasing the equipment was under $5,000. Ongoing capital expenditures to maintain the MPS amount to under $1,000/year, mainly for mannequin replacement parts. The main cost of this intervention is salary for the half-time effort of a faculty physician. However, before implementing the MPS, as indicated by the preliminary 4-center survey discussed above, faculty supervision of procedures was rare, limiting collection of professional fees for procedures. The salary support required for the MPS was partly offset by new, professional fee reimbursements; using our hospital’s Medicare reimbursement rates, this amounted to $63,253 over the first year of operation. If, as could be expected, the MPS resulted in reduction in procedure-related nosocomial complications such as infections and pneumothoraces,6, 10 additional savings would further offset the cost of staffing the MPS.

In 2006, the American Board of Internal Medicine eliminated the requirement that residents be taught how to perform any of the procedures we studied.21 Whereas recent data show that the spectrum and number of procedures being performed by General Internists in the United States has declined, approximately one quarter still perform LP, PC, TC, and CVC.2 Yet, even in an earlier era when Internists more regularly performed these procedures,18 residency procedure training was often inadequate.8 The new requirements will almost certainly cause further deterioration of procedure skills, possibly increasing risk to patients. The alternative, that General Internists will refer such procedures to invasive radiologists, is not a widely available option,22 especially in the smaller centers where Internists most commonly perform them.2 If Internists entering Hospitalist practices or subspecialty fellowships are not trained to do basic invasive procedures during their residencies, those programs will have to create structures to supply the needed training. The question of how to best teach procedures is important,3,23 but has been inadequately studied. Our study showed that a comprehensive, multifaceted, inpatient medical procedure rotation of 2 weeks duration for Internal Medicine residents resulted in marked improvement in their comfort and self-rated knowledge performing invasive procedures. Although additional work must be done to more fully evaluate the effects of this intervention, it could serve as a model for other programs.

Acknowledgment

The authors are indebted to the following people for making it possible to perform this study: Drs. Lee Tai, Advocate Christ Medical Center, Oak Lawn, IL; Michael McFarlane, MetroHealth Medical Center, Cleveland, OH; Richard Christie, St. Vincent Charity Hospital, Cleveland, OH; and K. V. Gopalakrishna, Fairview Hospital, Cleveland, OH. There were no specific sources of financial support for this study.

Conflict of Interest Statement None disclosed.

References

- 1.Policies and procedures for certification. Philadelphia: American Board of Internal Medicine; 1998.

- 2.Wigton RS, Alguire P. The declining number and variety of procedures done by general internists: a resurvey of members of the American College of Physicians. American College of Physicians Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(5):355–60. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Wigton RS. Measuring procedural skills. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125(12):1003–04. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Wickstrom GC, Kelley DK, Keyserling TC, Kolar MM, Dixon JG, Xie SX, et al. Confidence of academic general internists and family physicians to teach ambulatory procedures. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(6):353–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Hicks CM, Gonzalez R, Morton MT, Gibbons RV, Wigton RS, Anderson RJ. Procedural experience and comfort level in internal medicine trainees. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(10):716–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Sherertz RJ, Ely EW, Westbrook DM, Gledhill KS, Streed SA, Kiger B, et al. Education of physicians-in-training can decrease the risk for vascular catheter infection. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132(8):641–48. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Huang GC, Smith CC, Gordon CE, Feller-Kopman DJ, Davis RB, Phillips RS, et al. Beyond the comfort zone: residents assess their comfort performing inpatient medical procedures. Am J Med. 2006;119(1):71.e17–71.e24. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Wigton RS, Blank LL, Nicolas JA, Tape TG. Procedural skills training in internal medicine residencies. A survey of program directors. Ann Intern Med. 1989;111(11):932–38. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Anastakis DJ, Regehr G, Reznick RK, Cusimano M, Murnaghan J, Brown M, et al. Assessment of technical skills transfer from the bench training model to the human model. Am J Surg. 1999;177(2):167–70. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Martin M, Scalabrini B, Rioux A, Xhignesse M. Training fourth-year medical students in critical invasive skills improves subsequent patient safety. Am Surg. 2003;69(5):437–40. [PubMed]

- 11.Oxentenko AS, Ebbert JO, Ward LE, Pankratz VS, Wood KE. A multidimensional workshop using human cadavers to teach bedside procedures. Teach Learn Med. 2003;15(2):127–30. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Velmahos GC, Toutouzas KG, Sillin LF, Chan L, Clark RE, Theodorou D, et al. Cognitive task analysis for teaching technical skills in an inanimate surgical skills laboratory. Am J Surg. 2004;187(1):114–19. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Kohis-Gatzoulis JA, Regehr G, Hutchinson C. Teaching cognitive skills improves learning in surgical skills courses: a blinded, prospective, randomized study. Can J Surg. 2004;47(4):277–83. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Ramakrishna G, Higano ST, McDonald FS, Schultz HJ. A curricular initiative for internal medicine residents to enhance proficiency in internal jugular central venous line placement. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80(2):212–18. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Proano L, Jagminas L, Homan CS, Reinert S. Evaluation of a teaching laboratory using a cadaver model for tube thoracostomy. J Emerg Med. 2002;23(1):89–95. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2002;51(RR-10):1–29. [PubMed]

- 17.Chen H, Lillemoe KD, Sonnenday CJ. (eds.) In: Manual of common bedside surgical procedures. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000.

- 18.Wigton RS, Nicolas JA, Blank LL. Procedural skills of the general internist: a survey of 2500 physicians. Ann Intern Med. 1989;111(12):1023–34. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Wigton RS. Training internists in procedural skills. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116(12 Pt 2):1091–93. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Smith C, Gordon CE, Feller-Kopman D, Huang GC, Weingart SN, Davis RB, et al. Creation of an innovative inpatient medical procedure service and a method to evaluate house staff competency. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(5 Pt 2):510–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.American Board of Internal Medicine. Internal Medicine Policies. Available at: http://www.abim.org/certification/policies/imss/im.aspx#procedures. Accessed January 8, 2008.

- 22.Goldstein LB, Hey LA, Laney R. North Carolina stroke prevention and treatment facilities survey. Statewide availability of programs and services. Stroke. 2000;31(1):66–70. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Fincher RM. Procedural competence of internal medicine residents: time to address the gap. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(6):432–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]