Abstract

Epsin has been suggested to act as an alternate adaptor in several endocytic pathways. Its role in synaptic vesicle recycling remains, however, unclear. Here, we examined the role of epsin in this process by using the lamprey reticulospinal synapse as a model system. We characterized a lamprey ortholog of epsin 1 and showed that it is accumulated at release sites at rest and also at clathrin-coated pits in the periactive zone during synaptic activity. Disruption of epsin interactions, by presynaptic microinjection of antibodies to either the epsin-N-terminal homology domain (ENTH) or the clathrin/AP2 binding region (CLAP), caused profound loss of vesicles in stimulated synapses. CLAP antibody-injected synapses displayed a massive accumulation of distorted coated structures, including coated vacuoles, whereas in synapses perturbed with ENTH antibodies, very few coated structures were found. In both cases coated pits on the plasma membrane showed a shift to early intermediates (shallow coated pits) and an increase in size. Moreover, in CLAP antibody-injected synapses flat clathrin-coated patches occurred on the plasma membrane. We conclude that epsin is involved in clathrin-mediated synaptic vesicle endocytosis. Our results support a model, based on in vitro studies, suggesting that epsin coordinates curvature generation with coat assembly and further indicating that epsin limits clathrin coat assembly to the size of newly formed vesicles. We propose that these functions of epsin 1 provide an additional mechanism for generation of uniformly sized synaptic vesicles.

Keywords: adaptor, clathrin, ENTH domain, AP2, amphiphysin

Clathrin-mediated endocytosis is one of the most extensively characterized mechanisms for cellular internalization (1, 2). It is used to retrieve a variety of cargos, including receptors, channels, nutrients, and synaptic vesicle proteins. Depending on the cargo, the clathrin coat may differ in shape and molecular composition. The adaptor complex AP2 is the common module of the clathrin coat complex in different pathways functioning as a link between cargo and clathrin (2, 3). A group of cargo-selective alternative adaptors act in cooperation with AP2 to ensure specificity and efficacy of endocytosis. These molecules include AP180, CALM, HIP1, numb, Dab2, ARH, β-arrestin, stonin 2, and epsin. They recognize distinct cargo motifs and have been linked to specific clathrin-mediated pathways in different cell types (2–5).

Two of the alternate adaptors, AP180 and epsin 1, are enriched in neuronal synapses (6). They belong to a group of proteins containing an N-terminal globular module that binds phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2), the epsin N-terminal homology domain (ENTH)–adaptor protein 180 N-terminal homology domain (ANTH) (6). Previous studies have provided insight into the role of AP180 in coated vesicle formation. Mutation of AP180 in Drosophila and Caenorhabditis elegans resulted in increased variability in the size of synaptic vesicles (7, 8). In vitro studies demonstrated that addition of AP180 to clathrin and AP2 promotes the formation of coated pits of similar size on lipid monolayers (9). Together, these studies strongly link the function of AP180 to the control of synaptic vesicle size. The role of epsin in synaptic vesicle endocytosis still remains unclear.

Epsin 1 is a 550- to 600-aa-long protein (10). In addition to the ENTH domain, it contains two or three ubiquitin-interacting motifs (UIMs), one clathrin/AP2 binding region (CLAP), and three Arg-Pro-Phe (NPF) motifs. The NPF motifs bind eps15-homology (EH) domains of Eps15 and intersectin (11). The CLAP region in epsin 1 includes two clathrin boxes and eight Asp-Pro-Trp (DPW) motifs (10). The UIMs have been shown to bind monoubiquitin and polyubiquitin but also to be responsible for monoubiquitination of epsin itself (12, 13). The ENTH domain binds PIP2 with high affinity and upon binding forms a novel amphipathic helix in the N terminal (14). A model has been proposed based on in vitro experiments, in which the helix is inserted in the inner layer of the plasma membrane, thereby inducing membrane curvature and facilitating coated pit formation (14).

In the present study, we examine the role of epsin 1 in synaptic vesicle recycling. With the lamprey giant reticulospinal synapse (15) epsin 1 interactions were perturbed by microinjection of domain-specific antibodies. Our results suggest that epsin 1 participates in coat nucleation and regulation of coat size in central synapses.

Results

Characterization of a Lamprey Epsin Ortholog and Generation of Domain-Specific Antibodies.

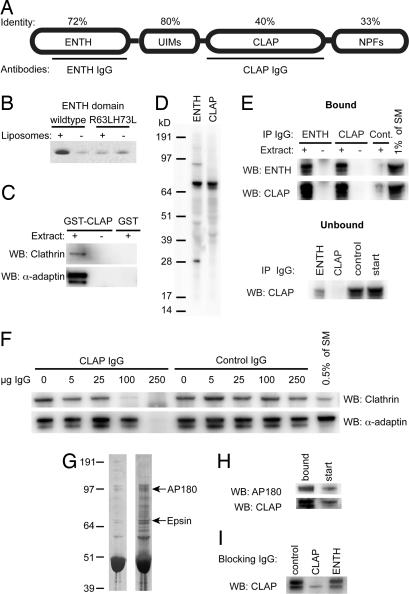

A lamprey epsin ortholog was partially cloned by PCR-based methods (see Methods for details). The transcript encodes a protein of 639 aa that resembles mammalian epsin 1 (Fig. 1A). Sequence alignment showed that the N terminal, including the ENTH domain and UIMs, were the most conserved parts (Fig. 1A). Critical residues in the PIP2-binding motif [supporting information (SI) Fig. S1] were conserved, suggesting a similar specificity for PIP2 as in mammals. The C terminal was less conserved except for homology at clathrin binding boxes (two), DPW motifs (eight), and NPF motifs (two). Different splice variants were also found (see Methods). The liposome-binding property of the ENTH domain was confirmed by a liposome sedimentation assay (Fig. 1B). As a control, a nonliposome binding mutant (R63LH73L) was used (14). Binding of clathrin and AP2 to GST-CLAP was shown in pull-down assays with lamprey brain extract (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Characterization of a lamprey epsin 1 ortholog. (A) Domain structure of lamprey epsin. Identity to human epsin 1 for each region is indicated in percentage. Antibodies were raised to residues 42–207 (ENTH) and 262–496 (CLAP) (black lines). (B) Liposome sedimentation assay with wild-type ENTH domain (with and without liposomes) and mutant ENTH domain (with and without liposomes), stained with Coomassie blue. (C) GST-CLAP pull-down with lamprey brain extract. Clathrin and AP2 were detected with clathrin heavy chain and α-adaptin antibodies, buffer, or extract with GST alone. (D) Protein extracts from lamprey brain analyzed by SDS/PAGE and Western blot using ENTH and CLAP antibodies. (E) (Upper) Immunoprecipitation of lamprey brain extract with ENTH and CLAP antibodies. Also shown are control incubations with buffer alone and with control IgGs (2.5% of the pellet was loaded). (Lower) Shown is the remaining signal in the unbound material, control IgG, and 1% of the starting material. (F) Western blot analysis of GST-CLAP pull-downs showing selective inhibition of the binding of clathrin and AP2 by CLAP antibodies but not by control IgGs. (G) Pull-down with the GST-β appendage domain of AP2 from lamprey brain extract. Coomassie staining (Left) and silver staining (Right) are shown. (H) Western blot analysis of bound material vs. start material with AP180 and epsin CLAP antibodies (at locations indicated in G). (I) Effects of epsin CLAP and epsin ENTH antibodies on epsin binding (from lamprey brain extract) to the GST-β appendage domain of AP2. Note the reduced binding of epsin induced by the CLAP antibodies.

Polyclonal antibodies were raised against the ENTH domain and the CLAP region, respectively. Western blot showed that both antibodies recognized a major band of ≈75 kDa in lamprey brain extract (Fig. 1D). To verify that the band recognized by each antibody corresponds to the same protein, immunoprecipitation was performed. The ENTH antibodies were found to recognize the 75-kDa protein in the CLAP IgG pellet (Fig. 1E) and the CLAP antibodies recognized the 75-kDa band in the ENTH IgG pellet, showing that the antibodies react with the same protein. Analysis of the unbound material showed that the 75-kDa band was almost completely depleted (Fig. 1E Lower). To test whether the CLAP antibodies inhibit the interaction of the CLAP region with AP2/clathrin, pull-down experiments were performed. Addition of increasing amounts of CLAP antibodies reduced the amount of bound clathrin and AP2 (Fig. 1F).

The efficacy of the ENTH antibodies was tested in a liposome tubulation assay. Consistent with previous electron microscopic studies (14) the ENTH domain induced numerous tubules at the light microscopic level (15.4 ± 0.8/100 μm2, mean ± SEM, n = 5; Fig. S2) along with an aggregation of liposomes. After addition of ENTH antibodies the number of tubules was markedly reduced (1.2 ± 0.4/100 μm2, mean ± SEM, n = 5, P < 0.001 vs. ENTH domain alone, Student's t test). No reduction occurred after addition of control antibodies (13.6 ± 1.2/100 μm2, mean ± SEM, n = 5) or CLAP antibodies (15.8 ± 1.4/100 μm2, mean± SEM, n = 5). These data indicate that the ENTH antibodies interfere with the ENTH—PIP2 interaction (14).

In other species epsin binds, along with AP-180, the β-appendage domain of AP2 (2, 16). We asked whether such binding occurs also in lamprey CNS. Pull-down with the β-appendage domain showed efficient binding of both AP180 and epsin (Fig. 1 G and H). By densitometry the AP180/epsin ratio was found to be 3:1. We also took advantage of the β-appendage domain assay to further test the specificity of the two epsin antibodies. The CLAP antibodies caused a strong reduction of epsin binding, whereas the ENTH antibodies did not (Fig. 1I), thus validating the distinct action of the two antibodies. The AP180 binding was not affected (data not shown).

Epsin Is Accumulated at Synaptic Coated Pits.

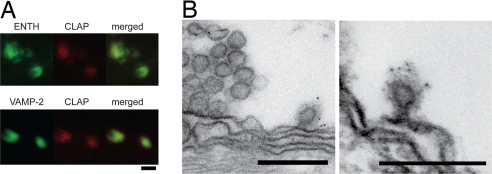

Comicroinjection of CLAP antibodies and ENTH antibodies was performed to investigate the localization of epsin within reticulospinal axons (Fig. 2A). The two antibodies coaccumulated at spots showing that they recognize the same protein in vivo and indicating that epsin is specifically localized at synaptic release sites. Colocalization of CLAP antibodies and VAMP-2 antibodies confirmed the synaptic localization (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Epsin is accumulated at synaptic regions and clathrin-coated pits. (A) (Upper) Confocal images from the axonal surface of a giant axon coinjected with Alexa488-labeled ENTH and Alexa546-labeled CLAP antibodies. (Lower) Confocal images from an axon coinjected with Alexa488-labeled VAMP-2 antibodies and Alexa546-labeled CLAP antibodies. (B) Electron micrographs of clathrin-coated pits at the periactive zone of a reticulospinal synapse stimulated with 30 mM K+ for 30 min and labeled with CLAP antibodies. Note the gold particles (5 nm) associated with clathrin-coated pits. (Scale bars: A, 1 μm; B, 200 nm.)

To examine whether epsin is associated with clathrin-coated pits induced by synaptic activity immunogold labeling was performed with CLAP antibodies. In synapses fixed at rest the gold particles were observed only in the vesicle cluster region (data not shown). In stimulated synapses gold particles were also found on clathrin-coated pits in the periactive zone (Fig. 2B; high K+ for 30 min). Quantification of gold particles confirmed that epsin is recruited to the periactive zone during activity. In stimulated synapses the periactive zone contained 4.4 ± 0.6 particles per center section (mean ± SEM, n = 5 synapses) compared with 0.9 ± 0.3 in unstimulated synapses (mean ± SEM, n = 5; P < 0.001, Student's t test). In an adjacent control area (see Methods), the particle density did not differ between stimulated (0.9 ± 0.3, mean ± SEM, n = 5) and unstimulated synapses (0.7 ± 0.3, mean ± SEM, n = 5) (P > 0.5, Student's t test). Thus, epsin is accumulated at synapses and associate with coated pits in the periactive zone during synaptic activity.

Antibody Perturbation of Epsin Impairs Synaptic Vesicle Recycling.

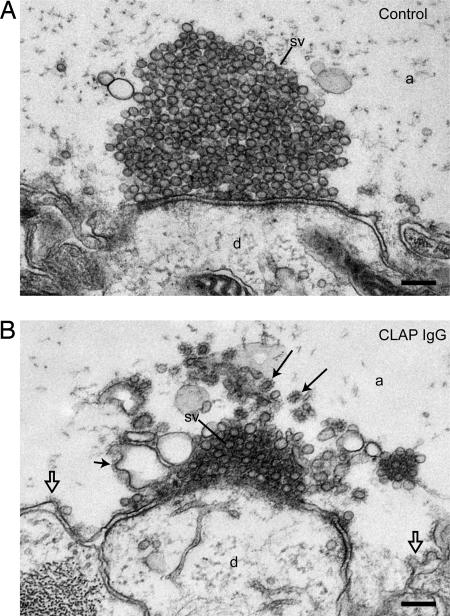

To study the role of epsin in clathrin-mediated synaptic vesicle endocytosis we microinjected CLAP antibodies into axons, which were then stimulated at 5 Hz for 30 min, fixed, and analyzed by EM. In uninjected axons (Fig. 3A) and axons injected with control IgGs (data not shown) synapses displayed large synaptic vesicle clusters (15). In axons injected with CLAP antibodies, however, marked changes were observed (Fig. 3B). The number of synaptic vesicles was reduced (injected axon: 150 ± 23, mean ± SEM, n = 7 synapses; control axon: 271 ± 37, mean ± SEM, n = 7 synapses; P < 0.05, Student's t test), and cisternae and coated structures occurred. We first focused the analysis on the plasma membrane in the periactive zone (Figs. 3 and 4). The number of clathrin-coated structures on the plasma membrane of CLAP antibody-injected axons (1.7 ± 0.3, mean ± SEM, n = 7 synapses) did not differ from that in control axons (2.0 ± 0.2, mean ± SEM, n = 7 synapses) (P > 0.5, Student's t test). The representation of different stages (17) was, however, changed, showing a shift to early intermediates (shallow coated pits) (Fig. 4 A and F).

Fig. 3.

Microinjection of CLAP antibodies impairs synaptic vesicle recycling. (A) Electron micrograph of a control synapse stimulated at 5 Hz for 30 min. (B) A synapse from an axon microinjected with CLAP antibodies and stimulated at 5 Hz for 30 min. Note the depletion of synaptic vesicles and the occurrence of clathrin-coated structures at cisternae (arrows) and the plasma membrane (open arrows). a, axoplasmic matrix; d, dendrite; sv, synaptic vesicles. (Scale bars: 200 nm.)

Fig. 4.

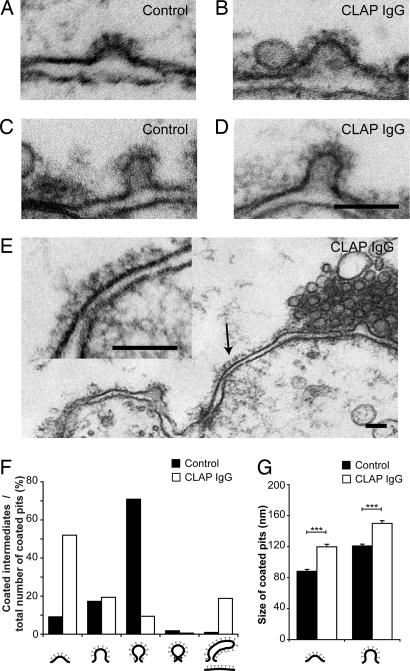

Microinjection of CLAP antibodies shifts the proportion of coated pits to early stages and increases their size. (A and B) Shallow coated pits from control (A) and CLAP antibody-injected (B). (C and D) Examples of nonconstricted (bucket-shaped) coated pits from control (C) and CLAP antibody-injected axons (D). (E) Flat clathrin-coated patch on the presynaptic membrane (arrows) from an axon microinjected with CLAP antibodies. A coated pit is also present to the left. (Scale bars: 100 nm.) (F) Quantitative analysis showing representation of different stages of coated pits in synapses microinjected with CLAP antibodies as compared with noninjected controls (n = 181 coated pits for CLAP antibody-injected axons, n = 109 coated pits for control synapses; P < 0.001 with χ2 test). (G) Length of the invaginated part of shallow coated pits (P < 0.001, Student's t test) and nonconstricted coated pits (P < 0.001, Student's t test; n = 15 coated pits for each condition).

The early intermediates were not only increased in number but also in size. Two stages of intermediates, shallow and nonconstricted (bucket-shaped), were examined. Both types were significantly larger in CLAP antibody-injected axons as compared with control axons (Fig. 4 A–D and G). Although the clathrin-coated pits were larger, there was no significant difference in synaptic vesicle diameter (in the cluster) in synapses from injected and control axons (injected axon: 47.8 ± 5.5 nm, mean ± SEM, n = 100 synaptic vesicles; control axon: 48.6 ± 5.8 nm, mean ± SEM, n = 100 synaptic vesicles; P = 0.28, Student's t test), thus suggesting that the enlarged coated intermediates were trapped at the plasma membrane. In addition, flat clathrin-coated plasma membrane patches (Fig. 4 E and F) were observed in CLAP antibody-injected axons, but not in control axons.

Another major change induced by the CLAP antibodies was the occurrence of cisternae in the vicinity of the vesicle cluster (injected axon: 35% ± 4, mean ± SEM, n = 7 synapses; control axon: 13% ± 3, mean ± SEM, n = 7 synapses; P < 0.001, Student's t test), many of which were associated with coated structures (Fig. 3B). These coated structures showed a heterogeneous morphology. They included pits and tubules, which appeared to be part of complex tubular networks (arrows in Fig. 3B). Coated tubular regions were in some cases seen to alternate with vacuolar structures (Fig. 5A). Some of these structures were connected to the plasma membrane (Fig. 5B). Moreover, large clathrin-coated vacuoles occurred (Figs. 3B and 5 C and D), some of which had pit-like extensions (short arrow in Fig. 3B; arrows in Fig. 5C). In total, the length of clathrin-coated membrane (including plasma membrane and cisternae) increased from 0.27 ± 0.04 in control axons to 1.30 ± 0.18 in CLAP antibody-injected axons (mean ± SEM; P < 0.001, Student's t test).

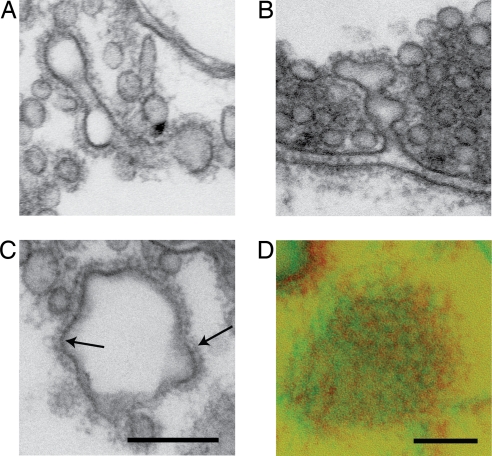

Fig. 5.

Microinjection of CLAP antibodies causes accumulation of enlarged coated structures. Electron micrographs of extended clathrin coats on membrane structures in synapses microinjected with CLAP antibodies. (A) Large coated structures with vacuolar and tubular regions. (B) Large clathrin-coated structure with connection to the plasma membrane. (C) Large clathrin-coated vacuolar structure with pit-like extensions (arrows). (D) Stereoscopic view of the surface of a vacuolar structure captured in the plane of sectioning (250-nm-thick section). Merge of two electron micrographs taken at ±8° is shown. (Scale bars: 200 nm.)

The above effects were strictly stimulus-dependent. When the CLAP antibodies were microinjected in axons maintained at rest in low Ca2+ solution, synapses contained large synaptic vesicle clusters. Very few clathrin-coated pits occurred (resting injected axon: 0.32 ± 0.12, mean ± SEM, n = 9 synapses; resting control axon: 0.05 ± 0.04, mean ± SEM, n = 6 synapses; P > 0.1, Mann–Whitney test; for stimulated axons; see Fig. 6B), whereas no coated cisternae were detected.

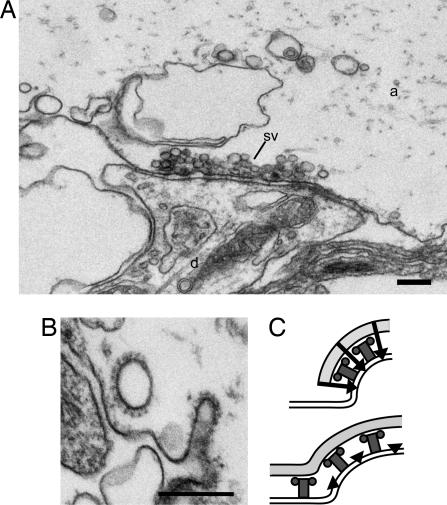

Fig. 6.

Microinjection of ENTH antibodies inhibits synaptic vesicle recycling. (A) Electron micrograph of a synapse stimulated at 5 Hz for 30 min from an axon microinjected with ENTH antibodies. Note the depletion of synaptic vesicles (compare with Fig. 3A), the presence of cisternae, and the absence of clathrin-coated intermediates. (B) Examples of coated structures with distorted morphology found in a different section of the synapse shown in A. a, axoplasmic matrix; d, dendrite; sv, synaptic vescicles. (Scale bars: 200 nm.) (C) Proposed role of epsin 1 in synaptic vesicle endocytosis. Epsin 1 (black) helps to generate membrane curvature, which is stabilized by interactions with the assembling coat (Upper). Interactions of epsin with clathrin (light gray) and AP2 (dark gray) also take part in restricting clathrin assembly to curved regions. After perturbation of epsins interactions with clathrin and AP2 (Lower) the stabilizing effect of epsin on curvature is disturbed. Moreover, clathrin assembly extends beyond the limit of the curved membrane.

We speculated that the abundance of distorted coated structures in CLAP antibody-injected axons could be caused by interference with epsin–clathrin/AP2 interactions (Fig. 1F). To perturb only the ENTH domain we used the ENTH antibodies. Axons were microinjected and stimulated as above. Analysis of synapses showed that the number of synaptic vesicles was markedly reduced (Fig. 6A; injected axon: 53 ± 6, mean ± SEM, n = 9 synapses; control axon: 286 ± 31, mean ± SEM, n = 6 synapses; P < 0.001, Student's t test), and many cisternae were present (injected axon: 57% ± 5 mean ± SEM, n = 9 synapses; control axon: 8% ± 1, mean ± SE, n = 6 synapses; P < 0.001, Student's t test). However, very few clathrin-coated structures occurred in synaptic regions. Accordingly, the total length of clathrin-coated membrane (including plasma membrane and cisternae) was significantly reduced (ENTH antibody-injected axons, 0.03 ± 0.01 mean ± SEM, n = 9 synapses; control axons, 0.26 ± 0.04, mean ± SEM, n = 6 synapses; P < 0.01, Student's t test), which thus contrasted with the increase seen in CLAP antibody-injected axons. Although the number of coated pits was very low in the ENTH antibody-injected axons, a similar shift to early stages of coated pits was observed (SI Text and Fig. S3), and a small number of coated structures with distorted morphology was detected (Fig. 6B). Analysis of synapses exposed to different concentrations of antibody (18) showed that there was a gradual decrease in the number of coated structures with increasing antibody concentration (data not shown).

Amphiphysin has previously been shown to codistribute with coat components at the synapse (19). We performed amphiphysin immunolabeling to monitor its distribution after ENTH perturbation. In control axons, labeling occurred on coated pits in the periactive zone and on the surface of synaptic vesicle clusters (Fig. S4). The overall labeling on the plasma membrane within 1 μm distance from the edge of the active zone (including labeled coated pits) was 14.2 ± 1.4 particles/μm membrane, mean ± SEM (n = 4). In ENTH antibody-injected axons the corresponding value was 6.8 ± 1.0 particles/μm membrane, mean ± SEM (n = 5; P < 0.05). The level of labeling on cisternae was, however, very low (1.8 ± 0.3 particles/μm membrane, mean ± SEM, P < 0.001 vs. control, Student's t test). Thus, after ENTH perturbation recruitment of amphiphysin to the periactive zone is reduced, whereas almost no amphiphysin is recruited to cisternae.

Discussion

Epsin 1 has been shown to be a coat component in several clathrin-mediated endocytic pathways. GFP-tagged epsin 1 was colocalized with clathrin spots in COS7 cells (20, 21). Studies using knock-down and dominant negative mutants have linked epsin 1 with transferrin uptake and EGF receptor uptake, respectively (14, 22, 23). However, epsin 1 appears not to be an obligitory component in endocytosis as it is not involved in clathrin-dependent uptake of Tetanus toxin into motoneurons (24). In the present study, we show that epsin 1 participates in clathrin-mediated synaptic vesicle endocytosis at a central synapse. By immunolabeling we found that epsin associates with activity-induced coated pits in the periactive zone. Acute perturbation of epsin with antibodies to either the ENTH domain or the CLAP region disrupted synaptic vesicle recycling.

After ENTH antibody injection the number of clathrin-coated structures in the periactive zone was strongly reduced, suggesting that nucleation of clathrin coats had been impaired. Amphiphysin, which associates with coat components (19), occurred on the plasma membrane, but very low levels occurred on cisternae, which presumably reflects a lack of coat components on these structures. This effect is consistent with a model that implies that epsin binding to PIP2 promotes membrane curvature along with recruitment of AP2, clathrin, and other coat components, including amphiphysin (14). The effects of CLAP-directed antibodies, however, suggest that this model is not fully applicable to an in vivo context as the number of coated structures did not show the expected decrease. The main effect of CLAP antibodies on coated pits at the plasma membrane was an increase in the relative abundance of shallow vs. invaginated coated pits, along with a size increase. On average, coated pits thus had less curvature after the perturbation. One possible explanation for this effect could be that ENTH-driven curvature formation requires continuous stabilization by the assembling coat. It is also possible that steric hindrance by the epsin-bound antibody prevented the formation of highly curved coated pits. The lack of a size difference of synaptic vesicles suggests that the enlarged coated pits did not proceed to vesiculation. However, we cannot exclude that they formed via an alternate adaptor, such as AP180 (see below). In addition to affecting the shape of coated pits, the CLAP antibodies induced large patches of clathrin. It is notable that similar patches have been seen after microinjection of a CLAP peptide and antibodies to the CLAP region of amphiphysin (19). These observations indicate that interactions between adaptors and clathrin/AP2 are important for preventing uncontrolled clathrin polymerization.

A unique feature of the synaptic vesicle cycle is its ability to generate vesicles of uniform size. The control of vesicle size probably involves several proteins. First, clathrin has been shown to be essential for curvature formation (25). Second, curvature formation is likely to involve AP180, and possibly amphiphysin and endophilin. These proteins interact with phospholipids, and amphiphysin and endophilin can generate and stabilize membrane curvature. Both AP180 and amphiphysin directly bind clathrin and AP2. The fact that Lamprey epsin bound the β-appendage domain along with AP180 suggests that the relative importance of these factors is similar to that in other species. Thus, the functions of these proteins, and epsin, are likely to be complementary and have a certain degree of redundancy. This redundancy can explain why knockouts of amphiphysin (26), AP180 (7, 8), and epsin 1 (P. De Camilli, personal communication) are viable. We propose (Fig. 6C) that epsin 1 controls synaptic vesicle size by linking curvature formation with coat assembly and restricting assembly to curved membrane regions. According to this model, epsin 1 can still contribute to curvature formation after perturbation of clathrin-AP2 interactions, but stabilization of curvature by the emerging coat is disturbed. Under these conditions epsin 1 may retain indirect connections with clathrin and AP2 via NPF–EH domain interactions, and UIMs may potentially also take part (1, 2). After perturbation of the ENTH domain, however, the adaptor function is entirely lost and the critical mass of adaptors needed for coat nucleation may not be reached. We observed epsin immunolabeling at deeply invaginated coated pits, but epsin has been reported to be partly lost upon purification of brain clathrin-coated vesicles (27). This loss could reflect a dissociation of epsin during coat maturation, possibly because of competition of low-affinity interactions with clathrin/AP2 in the emerging coat (16). Moreover, synaptojanin-mediated dephosphorylation of PIP2 during coat maturation may contribute to the loss of epsin at this stage (1).

Cisternae with clathrin-coated pits occur in control synapses after high-frequency stimulation (20 Hz) (17). At a moderate rate (5 Hz) a low number of cisternae is seen, whereas after perturbation of different endocytic proteins they become abundant (18, 19). These cisternae may reflect infolding caused by membrane expansion or an active uptake by bulk endocytosis (28). A recent study (29) has shown that perturbation of syndapin causes build-up of cisternae without affecting coated pits, suggesting that part of the cisternae may be caused by bulk endocytosis.

The effects of epsin perturbation on cisternae are in some aspects comparable with those on the plasma membrane. After ENTH antibody injection large cisternae lacking clathrin coats were present, which may reflect a blockade of coat nucleation in the bulk pathway. The CLAP antibodies caused a striking occurrence of clathrin-coated cisternae and tubules, consistent with a disruption of the coupling between curvature formation and coat assembly along with a lowered threshold for coat assembly (Fig. 6C). With regard to coated tubules it is possible that they reflect impaired fission caused by defective coat formation (30) and/or interference with auxilin-mediated uncoating (2). It is notable that coated structures were more abundant on cisternae than on the plasma membrane proper. Previous studies indicate that clathrin-mediated budding from cisternae is not identical to that at the plasma membrane. For instance, endophilin antibodies were shown to trap shallow coated pits at the plasma membrane, but deeply invaginated coated pits at cisternae (18). It is possible that the plasma membrane provides a more structured environment in which the dependence of CLAP interactions in controlling coat assembly is less pronounced. Lipid modification of the structured plasma membrane may be slow and possibly require recruitment of additional epsin-interacting partners involved in actin cytoskeleton reorganization. Indeed, recent studies have demonstrated that the ENTH domain may be involved in actin dynamics by interacting with GTPase-activating proteins linked to Cdc42 (31). As yet little is known about the molecular machinery of bulk endocytosis and how it differs from that of clathrin-mediated endocytosis. The present data suggest an involvement of epsin in both pathways.

Methods

Lamprey epsin 1 was cloned by PCR. Fusion proteins of the ENTH domain (amino acids 42–207) and the CLAP region (amino acids 262–496) were used to immunize rabbits. Antibodies were affinity-purified, labeled with Alexa dye, and pressure-microinjected into reticulospinal axons, which were either stimulated or maintained at rest in low calcium Ringer's solution (17, 18). After fixation and embedding, specimens were cut in serial ultrathin sections and analyzed by EM. For pre-embedding immunogold labeling spinal cords were fixed, and longitudinal sections (60 μm) were cut from the ventral side of the spinal cords with a vibratome, to make the interior of axons accessible to antibodies (32). For a detailed description of the methods see SI Text.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank Dr. Nikolay Tomilin for expert advice and Drs. Volker Haucke and Arndt Pechstein (both of Freie Universitaet, Berlin) for providing the AP2 appendage domain fusion protein. This work was supported by Swedish Research Council Grants 11287 (to L.B.) and 13473 (to O.S.), Human Frontier Science Program Grant RGP0034/2002C, Network of European Neuroscience Institutes, Swedish Foundation for International Cooperation in Research and Higher Education (STINT), and Knut and Alice Wallenbergs Stiftelse.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The sequence reported in this paper has been deposited in the GenBank database (accession no. EU623434).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0710267105/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Jung N, Haucke V. Clathrin-mediated endocytosis at synapses. Traffic. 2007;8:1129–1136. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2007.00595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ungewickell EJ, Hinrichsen L. Endocytosis: Clathrin-mediated membrane budding. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2007;19:417–425. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schmid EM, McMahon HT. Integrating molecular and network biology to decode endocytosis. Nature. 2007;448:883–888. doi: 10.1038/nature06031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Traub LM. Sorting it out: AP-2 and alternate clathrin adaptors in endocytic cargo selection. J Cell Biol. 2003;163:203–208. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200309175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diril MK, Wienisch M, Jung N, Klingauf J, Haucke V. Stonin 2 is an AP-2-dependent endocytic sorting adaptor for synaptotagmin internalization and recycling. Dev Cell. 2006;10:233–244. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Itoh T, De Camilli P. BAR, F-BAR (EFC), and ENTH/ANTH domains in the regulation of membrane-cytosol interfaces and membrane curvature. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1761:897–912. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang B, et al. Synaptic vesicle size and number are regulated by a clathrin adaptor protein required for endocytosis. Neuron. 1998;21:1465–1475. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80664-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nonet ML, et al. UNC-11, a Caenorhabditis elegans AP180 homologue, regulates the size and protein composition of synaptic vesicles. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:2343–2360. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.7.2343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ford MG, et al. Simultaneous binding of PtdIns(4,5)P2 and clathrin by AP180 in the nucleation of clathrin lattices on membranes. Science. 2001;291:1051–1055. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5506.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen H, et al. Epsin is an EH-domain-binding protein implicated in clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Nature. 1998;394:793–797. doi: 10.1038/29555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Legendre-Guillemin V, Wasiak S, Hussain NK, Angers A, McPherson PS. ENTH/ANTH proteins and clathrin-mediated membrane budding. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:9–18. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oldham CE, Mohney RP, Miller SL, Hanes RN, O'Bryan JP. The ubiquitin-interacting motifs target the endocytic adaptor protein epsin for ubiquitination. Curr Biol. 2002;12:1112–1116. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00900-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Polo S, et al. A single motif responsible for ubiquitin recognition and monoubiquitination in endocytic proteins. Nature. 2002;416:451–455. doi: 10.1038/416451a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ford MG, et al. Curvature of clathrin-coated pits driven by epsin. Nature. 2002;419:361–366. doi: 10.1038/nature01020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brodin L, Shupliakov O. Giant reticulospinal synapse in lamprey: Molecular links between active and periactive zones. Cell Tissue Res. 2006;326:301–310. doi: 10.1007/s00441-006-0216-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schmid EM, et al. Role of the AP2 β-appendage hub in recruiting partners for clathrin-coated vesicle assembly. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e262. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gad H, Low P, Zotova E, Brodin L, Shupliakov O. Dissociation between Ca2+-triggered synaptic vesicle exocytosis and clathrin-mediated endocytosis at a central synapse. Neuron. 1998;21:607–616. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80570-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ringstad N, et al. Endophilin/SH3p4 is required for the transition from early to late stages in clathrin-mediated synaptic vesicle endocytosis. Neuron. 1999;24:143–154. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80828-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Evergren E, et al. Amphiphysin is a component of clathrin coats formed during synaptic vesicle recycling at the lamprey giant synapse. Traffic. 2004;5:514–528. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9219.2004.00198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zoncu R, et al. Loss of endocytic clathrin-coated pits upon acute depletion of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:3793–3798. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611733104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rappoport JZ, Kemal S, Benmerah A, Simon SM. Dynamics of clathrin and adaptor proteins during endocytosis. Am J Physiol. 2006;291:C1072–C1081. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00160.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Itoh T, et al. Role of the ENTH domain in phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate binding and endocytosis. Science. 2001;291:1047–1051. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5506.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vanden Broeck D, De Wolf MJ. Selective blocking of clathrin-mediated endocytosis by RNA interference: Epsin as target protein. BioTechniques. 2006;41:475–484. doi: 10.2144/000112265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deinhardt K, Berninghausen O, Willison HJ, Hopkins CR, Schiavo G. Tetanus toxin is internalized by a sequential clathrin-dependent mechanism initiated within lipid microdomains and independent of epsin1. J Cell Biol. 2006;174:459–471. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200508170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hinrichsen L, Meyerholz A, Groos S, Ungewickell EJ. Bending a membrane: How clathrin affects budding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:8715–8720. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600312103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Di Paolo G, et al. Decreased synaptic vesicle recycling efficiency and cognitive deficits in amphiphysin 1 knockout mice. Neuron. 2002;33:789–804. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00601-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hawryluk MJ, et al. Epsin 1 is a polyubiquitin-selective clathrin-associated sorting protein. Traffic. 2006;7:262–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2006.00383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Andersson F, Jakobsson J, Löw P, Shupliakov O, Brodin L. Perturbation of syndapin/PACSIN impairs synaptic vesicle recycling evoked by intense stimulation. J Neurosci. 2008 doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1754-07.2008. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Royle SJ, Lagnado L. Endocytosis at the synaptic terminal. J Physiol (London) 2003;553:345–355. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.049221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Di Paolo G, De Camilli P. Does clathrin pull the fission trigger? Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:4981–4983. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0930650100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aguilar RC, et al. Epsin N-terminal homology domains perform an essential function regulating Cdc42 through binding Cdc42 GTPase-activating proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:4116–4121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510513103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Evergren E, et al. A pre-embedding immunogold approach for detection of synaptic endocytic proteins in situ. J Neurosci Methods. 2004;135:169–174. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2003.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.