Abstract

Tumor hypoxia is linked to increased metastatic potential, but the molecular mechanisms coupling hypoxia to metastasis are poorly understood. Here, we show that Notch signaling is required to convert the hypoxic stimulus into epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT), increased motility, and invasiveness. Inhibition of Notch signaling abrogated hypoxia-induced EMT and invasion, and, conversely, an activated form of Notch could substitute for hypoxia to induce these processes. Notch signaling deploys two distinct mechanisms that act in synergy to control the expression of Snail-1, a critical regulator of EMT. First, Notch directly up-regulated Snail-1 expression by recruitment of the Notch intracellular domain to the Snail-1 promoter, and second, Notch potentiated hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α) recruitment to the lysyl oxidase (LOX) promoter and elevated the hypoxia-induced up-regulation of LOX, which stabilizes the Snail-1 protein. In sum, these data demonstrate a complex integration of the hypoxia and Notch signaling pathways in regulation of EMT and open up perspectives for pharmacological intervention with hypoxiainduced EMT and cell invasiveness in tumors.

Keywords: E-cadherin, lysyl oxidase, Snail

Hypoxia (reduced oxygen) has received considerable attention as an inducer of tumor metastasis, and there is a strong correlation among tumor hypoxia, metastasis, and poor patient outcome (1, 2); for review, see refs. 3 and 4. It has been proposed that the initial steps in metastasis involve an epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT)-like process (5). EMT converts cells from an epithelial, nonmotile morphology to become migratory and prone to invade other tissues (5–7). EMT is accompanied by specific changes in gene expression, such as down-regulation of E-cadherin (6, 7). The E-cadherin promoter is repressed by several transcriptional repressors (8), including the zinc finger transcription factor Snail-1 (9); for review, see ref. 10. In keeping with this, Snail factors are potent inducers of EMT. Up-regulation of Snail-1 correlates with metastasis and poor prognosis, whereas silencing of Snail-1 is critical for reducing tumor growth and invasiveness (11, 12); for review, see ref. 10.

When tumors outgrow the oxygen-supplying capacity of the vasculature, the low oxygen levels are sensed by a hypoxic response machinery in the cell. Low oxygen levels inactivate prolyl hydroxylases, which, in normoxia, hydroxylate hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α), making it a substrate for ubiquitylation by the von Hippel–Lindau (VHL) E3 ubiquitin ligase complex, followed by degradation by the proteasome (13, 14). This results in very low steady-state levels of HIF-1α during normoxia and accumulation in hypoxia. When stabilized in hypoxia, HIF-1α dimerizes with HIF-1β (ARNT) and activates downstream genes involved in the canonical hypoxic response via HRE elements in their promoters (15, 16). Mutations affecting VHL or growth factor-induced expression of HIF-1α can lead to tumorigenesis (17).

The molecular mechanisms that relay the hypoxia signal into EMT and metastasis are still largely elusive, and it is an open issue whether the “canonical” hypoxic response, i.e., via HIF-1α binding to hypoxia-response elements (HREs) in the promoter, is used or whether alternative molecular readouts cause EMT in response to hypoxia. The Notch signaling pathway is an attractive candidate as a mediator for an alternative readout between hypoxia and EMT in tumor cells, because integration between Notch signaling and hypoxia was recently demonstrated in the control of stem cell differentiation (18). Furthermore, Notch can up-regulate Snail-1 and induce EMT in normoxia during normal development in cardiac and kidney tubular cell differentiation (19, 20), although the detailed molecular mechanism for how Notch controls Snail-1 expression remains to be established. Finally, deregulated Notch signaling correlates with cancer, for example in T cell lymphoblastic leukemia, where the majority of patients carry mutations in NOTCH 1 (21), and in breast cancer, where elevated expression of the activated form of Notch is observed (22, 23). The core Notch signaling pathway is composed of relatively few components (24). Ligand activation results in two proteolytic cleavage events in the transmembrane Notch receptor. This ultimately leads to liberation of the Notch intracellular domain (NICD), which constitutes the activated form of the receptor (24, 25). In the nucleus, NICD interacts with the DNA-binding protein CSL (RBP-J, Su(H), Rbpsuh, Lag-1) to regulate expression of downstream genes (24).

In this article, we provide evidence for a hypoxia/Notch/EMT axis in tumor cells, where Notch serves as a critical intermediate in conveying the hypoxic response into EMT. Hypoxia-induced increased motility and invasiveness of the tumor cells require Notch signaling, and activated Notch mimicked hypoxia in the induction of EMT. In this process, Notch signaling controls Snail-1 expression by two distinct but synergistic mechanisms, involving both direct transcriptional activation of Snail-1 and an indirect mechanism operating via lysyl oxidase (LOX), leading to elevated Snail-1 protein levels.

Results and Discussion

Hypoxia Induces the Notch Downstream Response in Different Tumor Cell Types.

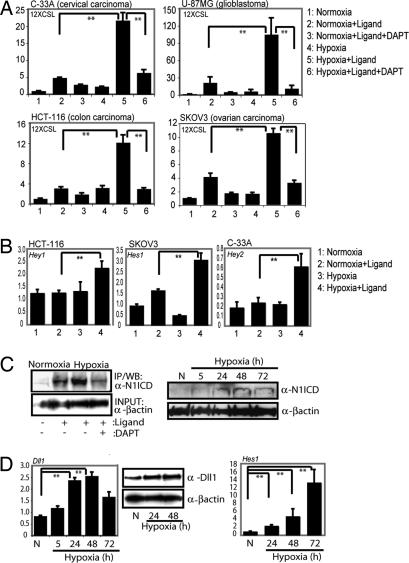

To address whether hypoxia potentiates the Notch downstream response in a tumor context, we examined the effect of hypoxia on the Notch signaling pathway in tumor cell lines of cervical (C-33A), colon (HCT-116), glioma (U-87MG), and ovarian (SKOV-3) origin. Coculture of these cell lines with Jagged 1-expressing cells resulted in a low level of activation of the Notch reporter construct 12XCSL-luc [see supporting information (SI) Fig. S1A for details] in normoxia and a substantially elevated response under hypoxic conditions (1% O2) (Fig. 1A). The increase in reporter gene expression was abrogated by the γ-secretase inhibitor (GSI) DAPT (Fig. 1A), which inhibits the final proteolytic cleavage of the Notch receptor. The hypoxia-potentiated Notch signaling was further corroborated by elevated expression of Notch downstream genes in hypoxia (Fig. 1B). In sum, these data show that Notch signaling is augmented by hypoxia in various tumor cell lines.

Fig. 1.

Hypoxia potentiates Notch signaling in tumor cells. (A) C-33 A, HCT-116, U-87 MG, and SKOV-3 cells cocultured with 3T3-Babe (3T3-B) or 3T3-Jagged (ligand) cells kept at normoxia or hypoxia in the presence or absence of the γ-secretase inhibitor (DAPT), as indicated. Notch activity was measured by 12XCSL-luc activation. (B) Expression of Notch downstream genes (Hey1, Hes1, or Hey2, as indicated) measured by quantitative PCR in HCT-116, SKOV-3, and C-33 A cells activated by coculture as above, in normoxia or hypoxia. (C) (Left) SKOV-3 cells, immunopreciptated for activated Notch 1 after coculture with 3T3-B or 3T3-Jagged (3T3-J) cells kept at normoxia or hypoxia in the absence or presence of GSI (Right). Western blot of N1ICD and β-actin expression in SKOV-3 cells subjected to normoxia (N) or hypoxia for 5, 24, 48, or 72 h. For the immunoprecipitation experiment (Left), the β-actin control is run on a separate gel. (D) (Left) Quantitative PCR analysis of Delta-like 1 (Dll1) mRNA expression in SKOV-3 cells kept at normoxia or hypoxia for 5, 24, 48, or 72 h. (Center) Western blot showing expression of DLL1 in normoxia and hypoxia. (Right) Quantitative PCR analysis of Hes 1 mRNA expression in SKOV-3 cells kept at normoxia or hypoxia for 24, 48, or 72 h. Note that in this experiment, a small up-regulation of Hes1 expression was observed already at 24 h, which is in contrast to the data in B, suggesting that Hes1 up-regulation may be somewhat variable. Values are presented as mRNA expression relative to expression of β-actin mRNA. Values are significant at **, P < 0.01 and *, P < 0.05, as indicated in the figure. Graphs represent average of three (A and B) or two (D) independent experiments.

Hypoxia Leads to Increased Levels of N1ICD and Up-Regulation of Notch Ligand Expression.

The elevated Notch response after hypoxia could result from effects at various levels in the Notch signaling pathway. Ligand-dependent activation of SKOV-3 cells resulted in increased levels of N1ICD, and the amount of accumulated N1ICD was further elevated in hypoxia (Fig. 1C Left). The low level of N1ICD found in SKOV-3 cells in the absence of ligand stimulation (26) was also elevated by hypoxia, reaching a maximum at 24–48 h after the hypoxic switch (Fig. 1C Right). On the ligand side, up-regulation of Delta-like 1 (Dll1) mRNA and protein was observed in SKOV-3 cells subjected to hypoxia (Fig. 1D). The increase in ligand expression and Notch ICD levels was paralleled by an increase in expression of the Notch target gene Hes-1 in SKOV-3 cells (Fig. 1D). It is of note that elevated ligand levels and stabilization of Notch ICD are likely to act synergistically to increase the Notch signaling output. Furthermore, these data show that hypoxia not only can cooperate with preexisting Notch signaling but can also induce Notch signaling by increasing the level of Notch ligands.

Hypoxia-Induced EMT and E-Cadherin Down-Regulation Require Notch Signaling.

The ovarian carcinoma cell line SKOV-3 has been used to study the loss of epithelial features and gain of a mesenchymal phenotype in response to hypoxia (27). We cultured SKOV-3 cells under hypoxic conditions or exposed the cells to the hypoxia-mimicking compound CoCl2. Both treatments induced morphological and molecular changes typical of EMT, i.e., cells converted from an epithelial to a more mesenchymal phenotype, down-regulated E-cadherin and β-catenin, and up-regulated vimentin, N-cadherin, and fibronectin (Fig. S1 B and D), in keeping with previous observations (27). Similar data were obtained for the breast cancer cell line MCF-7 (Fig. S1 C and D).

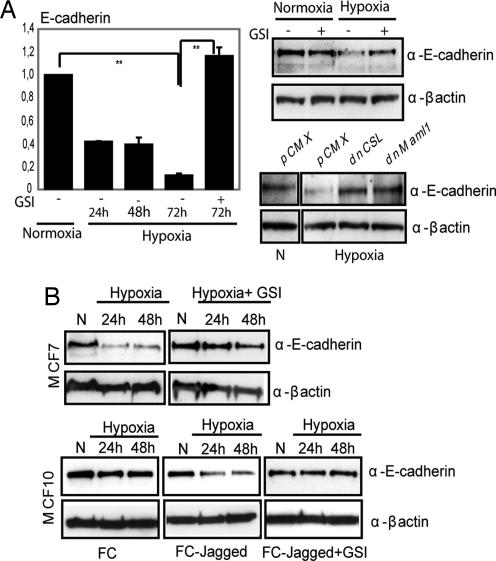

To assess the involvement of Notch in hypoxia-induced EMT in SKOV-3 cells, we inhibited Notch signaling by GSI or by expression of dominant-negative forms of CSL or Maml-1, key components in the Notch signaling cascade and present in the Notch ICD transcriptional complex (28). Inhibition of Notch signaling abrogated the down-regulation of E-cadherin mRNA observed during hypoxia (Fig. 2A), and the epithelial morphology was retained (Fig. S2A). Similarly, down-regulation of E-cadherin protein levels was observed after hypoxia and abrogated by GSI or transfection of dominant negative CSL or Maml1 (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, down-regulation of another cell-adhesion protein, occludin (data not shown), and reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton were substantially inhibited by GSI (Fig. S2A).

Fig. 2.

Hypoxia-mediated EMT requires Notch. (A) Quantitative PCR analysis of E-cadherin mRNA expression in SKOV-3 cells kept at normoxia or treated with hypoxia for the indicated time (Left). Values represent average values of three independent experiments and are significant at **, P < 0.01 and *, P < 0.05 as indicated. Western blot analysis of E-cadherin protein levels in SKOV-3 cells cultured at normoxia or hypoxia in the absence or presence of GSI (Upper Right) or in SKOV-3 cells transfected with empty vector (PCMX), dnCSL, or dnMaml1 (Lower Right). (B) E-cadherin protein expression in MCF7 cells in normoxia (N) or hypoxia (Upper). E-cadherin expression in MCF10 cells grown on recombinant FC domain or recombinant Jagged, to activate Notch signaling, in normoxia and hypoxia in the presence of absence of GSI as indicated (Lower).

The GSI data would suggest that a certain endogenous level of Notch signaling is required for hypoxia to down-regulate E-cadherin expression. To test this, we analyzed E-cadherin regulation in two breast cancer cell lines with low (blocked because of high activity of Numb; MCF10) and high (MCF7) levels of Notch signaling (Fig. S2B). Hypoxia induced down-regulation of E-cadherin in MCF7 cells (Fig. 2B Upper) but not in the MCF10 cells (Fig. 2B Lower Left), and it was only when MCF10 cells were grown on immobilized Jagged1 to activate Notch signaling that hypoxia induced down-regulation of E-cadherin (Fig. 2B Lower Center). This ligand-induced down-regulation was blocked by GSI (Fig. 2B Lower Right). Taken together, these data indicate that hypoxia-induced EMT requires Notch signaling and that cells with blocked or too-low endogenous Notch signaling are refractory to hypoxia-induced EMT and E-cadherin down-regulation.

Hypoxia-Induced EMT and E-Cadherin Down-Regulation Can Be Mimicked by N1ICD During Normoxia.

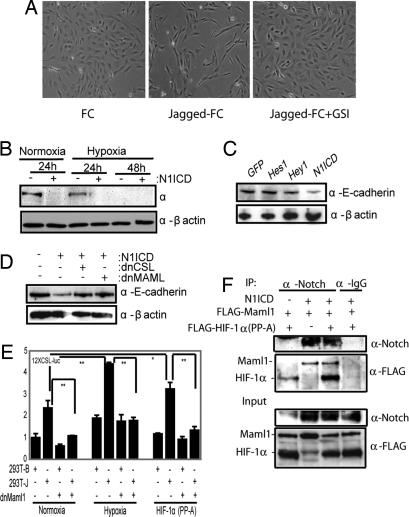

Because hypoxia-induced EMT required Notch signaling, we asked whether N1ICD could substitute for hypoxia in inducing EMT. Culturing of the SKOV-3 cells on immobilized Jagged-1 ligand under normoxic conditions induced morphological changes similar to what was observed in hypoxia, and the morphological change could be abrogated by GSI treatment (Fig. 3A). Expression of N1ICD led to a reduction in E-cadherin (Fig. 3B) and occludin (data not shown) levels during normoxia, and N1ICD was considerably more effective in down-regulating E-cadherin protein levels than Hes-1 and Hey-1 (Fig. 3C), indicating that E-cadherin down-regulation was mediated directly downstream of N1ICD rather than further down in the Notch signaling cascade.

Fig. 3.

Activation of Notch can mimic hypoxia-induced EMT. (A) Phase contrast images of SKOV-3 cells grown on recombinant FC or FC-Jagged in the presence or absence of GSI in normoxia. The same number of cells was seeded in each experiment. (B) Western blot analysis of endogenous E-cadherin protein levels in SKOV-3 cells kept at normoxia or hypoxia after transfection of N1ICD. (C) Western blot analysis of E-cadherin expression in SKOV-3 cells after infection with N1ICD, Hes-1, Hey-1, or EGFP. (D) E-cadherin protein levels after cotransfection of N1ICD with dnCSL or dnMaml1 at normoxia. (E) 12XCSL-luciferase activation in 293T cells cocultured with wild-type (−) or Jagged1-expressing 293T 293T-J) cells transfected with dnMaml1, treated with hypoxia or transfected with HIF-1α(PP-A). (F) Coimmunoprecipitation analysis of HIF1α–N1ICD–Maml1 interaction. Notch was immunoprecipitated from 293T cells transfected with N1ICD, FLAG-Maml1, and FLAG-HIF-1α(PP-A) as indicated, and the presence of coimmunopecipitated Maml1 and HIF-1α was detected by Western blot analysis. The input control is shown below. Values are significant at **, P < 0.01 and *, P < 0.05 as indicated.

N1ICD-induced repression of E-cadherin expression in SKOV-3 cells could be substantially abrogated when N1ICD was coexpressed with either dominant-negative CSL or Maml1 (Fig. 3D). Furthermore, dominant-negative Maml1 blocked ligand-mediated induction of 12XCSL-luciferase expression after hypoxia or introduction of a normoxically stabilized form of HIF-1α (PP-A) in normoxia (Fig. 3E). These data suggest that HIF-1α and Maml1 are present in the same transcriptional complex. In support of this notion, immunoprecipitation experiments revealed an interaction between N1ICD and both Maml1 and HIF-1α (Fig. 3F). The small amount of HIF-1α immunoprecipitated in cells not transfected with N1ICD is probably a consequence of a low level of endogenous Notch expression in these cells. In sum, these data show that N1ICD can substitute for hypoxia in controlling EMT and E-cadherin expression and that E-cadherin regulation requires CSL and Maml1 in addition to N1ICD.

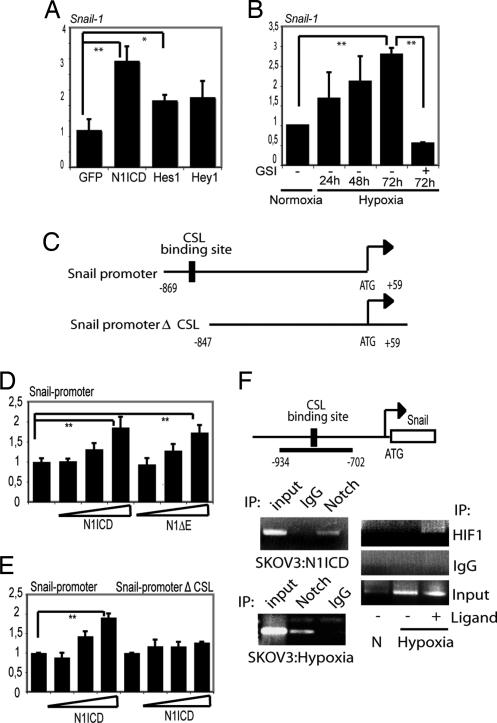

Notch Directly Regulates Expression of Snail-1.

Because Snail-1 is an important regulator of E-cadherin expression, we asked whether the effects of Notch on E-cadherin expression are mediated via N1ICD regulating Snail-1 at the transcriptional level. Snail-1 mRNA was up-regulated by N1ICD expressed from an adenoviral vector in the SKOV-3 cells compared with a control vector expressing EGFP or expression of Hes-1 or Hey-1 (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, hypoxia-induced up-regulation of Snail-1 mRNA in SKOV-3 cells was abrogated by GSI treatment (Fig. 4B). In Fig. S3, data are presented indicating that Notch signaling alone was sufficient to induce Snail-1 expression and that concomitant activation of the PI3-kinase/AKT, Ras/MAP kinase, TGF-β, or Wnt pathways is not required.

Fig. 4.

Snail-1 is a direct downstream target of Notch. (A and B) Quantitative PCR analysis of Snail-1 expression in SKOV-3 cells after adenoviral infection of N1ICD (NICD), Hes-1, Hey-1, or EGFP (A) or after exposure to hypoxia in the presence or absence of GSI (B). (C) Schematic depiction of the Snail-1 promoter constructs used in the study: the promoter containing (Snail-promoter) or lacking (Snail-promoterΔCSL) the CSL-binding site. (D) Snail1-luciferase activation by transfection of N1ICD or N1 ΔE. (E) Activation of the two promoter constructs shown in C by N1ICD. (F) Schematic representation of the Snail1 promoter with the amplified promoter region and the position of the CSL-binding sites denoted. Below the schematic representation, ChIP analysis of recruitment of N1ICD to the Snail-1 promoter after adenoviral infection of N1ICD into SKOV-3 cells (Upper Left) of for endogenous N1ICD after hypoxia in SKOV-3 cells (Lower Left) is shown. (Right) PCR amplification of the Snail-1 promoter after immunoprecipitation for N1ICD. ChIP analysis of recruitment of HIF-1α to the Snail-1 promoter after coculture with 3T3-Jagged1 (3T3-J) or 3T3-Babe (3T3-B) cells under normoxia or hypoxia and PCR amplification of the Snail-1 promoter after immunoprecipitation for HIF-1α are shown. Values are significant at **, P < 0.01 and *, P < 0.05, as indicated in A, B, D, and E. Values indicate the average of at least three independent experiments.

We identified a consensus CSL-binding motif (29) located at −847 to −839 bp upstream of the transcription start in the Snail-1 promoter (Fig. 4C). A 0.9 kb Snail-1 promoter-luciferase reporter, which encompasses the CSL-binding site (Fig. 4C), was activated in a dose-dependent manner by expression of N1ICD or Notch 1 ΔE [a membrane-tethered ligand-independent form of Notch (30)] (Fig. 4D). Deletion of the CSL-binding site (Snail promoterΔCSL-luc, Fig. 4C) abolished Notch-induction (Fig. 4E). We next showed by ChIP assays that N1ICD in infected SKOV-3 cells was recruited to the region of the Snail-1 promoter encompassing the −847/839 CSL-binding site (Fig. 4F). Recruitment of N1ICD was also observed in hypoxic SKOV-3 cells at endogenous levels of Notch signaling (Fig. 4F Lower).

Given the interaction between N1ICD and HIF-1α (Fig. 3F), we then asked whether HIF-1α accompanied N1ICD to the Snail-1 promoter. The data in Fig. 4F (Right) show that HIF-1α was detected at the Snail-1 promoter only under conditions of combined hypoxia and Notch-ligand stimulation. Further support for a role of HIF-1α in controlling Snail-1 expression comes from experiments in a renal carcinoma cell line (RCC), which is deficient in VHL and, consequently, has high HIF-1α levels. Stable reintroduction of VHL into the RCC cell line (RCC-VHL) reduced Snail-1 expression, whereas overexpression of N1ICD in the RCC-VHL cells increased Snail-1 mRNA levels (Fig. S4). Treatment of the RCC cells with GSI reduced the Snail-1 mRNA levels (data not shown). These data are in good agreement with a recent report by Evans et al. (31). Collectively, these data demonstrate that N1ICD transcriptionally regulates Snail-1, in keeping with a previous report (19), and extend this study by demonstrating that Snail-1 is a direct transcriptional target of Notch and that HIF-1α is recruited to the Snail-1 promoter only by the combination of hypoxia and active Notch signaling.

Notch Signaling Indirectly Up-Regulates Expression of LOX, Leading to Increased Levels of the Snail-1 Protein in Hypoxia.

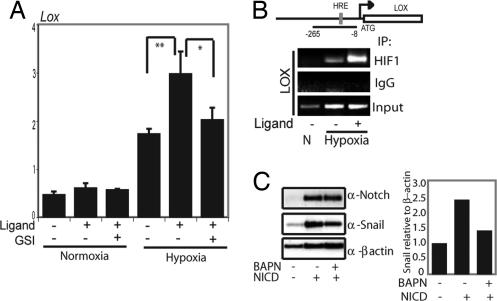

LOX was recently shown to link hypoxia to tumor invasion (32). Because LOX proteins also stabilize the Snail protein (33), we tested whether Notch would act in synergy with LOX to regulate Snail activity in hypoxia. As expected (32), hypoxia up-regulated the level of LOX mRNA in SKOV-3 cells (Fig. 5A). Interestingly, LOX expression was further increased by activation of Notch signaling by coculture with Notch ligand-expressing cells under hypoxic conditions, and Notch-mediated up-regulation was abrogated by GSI treatment (Fig. 5A). The Notch-induced elevation of LOX mRNA expression was observed only in hypoxia and not in normoxia (Fig. 5A). These data indicate that LOX is not a direct downstream gene of Notch, and in keeping with this notion, we could not identify any potential CSL-binding sites in a 2-kb proximal LOX promoter fragment, recently shown to respond to hypoxic stimulation (32). Furthermore, N1ICD did not bind to the LOX promoter at any detectable level, as assessed by ChIP analysis (data not shown). We therefore tested whether the recruitment of HIF-1α to the LOX promoter was altered by Notch signaling in hypoxia. By ChIP analysis, we showed that HIF-1α was recruited to the part of the LOX promoter containing a functional HRE (32). Recruitment of HIF-1α was observed only in hypoxia, and the recruitment was augmented when the cells were cocultured with cells expressing Notch ligand (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Notch signaling enhances hypoxia-induced activation of LOX transcription. (A) Quantitative PCR analysis of LOX expression in SKOV-3 cells cocultured with 3T3-Babe (3T3-B) or 3T3-Jagged (3T3-J) cells kept at normoxia or treated with hypoxia for 16 h in the absence or presence of GSI. Values are significant at **, P < 0.01 and *, P < 0.05 as indicated. Values represent the average of three independent experiments. (B) Schematic depiction of the LOX promoter with the PCR-amplified promoter region and the location of the HRE sites denoted. For the ChIP experiments, SKOV-3 cells were cocultured with either 3T3-J cells or 3T3-B cells at normoxia or hypoxia, as indicated. PCR amplification of the LOX promoter after immunoprecipitation of HIF-1α. (C) Western blot analysis of Snail-1 expressed from a heterologous promoter to analyze Snail-1 protein stability. SKOV-3 cells were transfected with wild-type Snail-1 and N1ICD or an empty vector and subjected to hypoxia in the presence or absence of the LOX inhibitor BAPN (Left). Quantification of the Western blot (Snail-1/β-actin intensity) is shown (Right).

The Notch-mediated elevation of LOX expression in hypoxia would be expected to lead to further stabilization, and thus higher levels, of the Snail-1 protein, because it is stabilized by LOX (34). To test this, we expressed wild-type Snail-1 from a heterologous promoter (to avoid Notch-mediated transcriptional regulation) in SKOV-3 cells and analyzed the levels of Snail-1 protein in the presence of absence of N1ICD in hypoxia. Notch signaling increased Snail-1 protein levels, and the increase was reduced by treatment with the LOX inhibitor β-aminoproprionitrile (BAPN) (Fig. 5C). Similarly, when ligand-induced Notch activation was combined with BAPN treatment, the Notch-mediated up-regulation of Snail-1 protein levels was reduced by BAPN (Fig. S5 A and B). Furthermore, the observed increased stability of Snail-1 in ligand-activated cells was blocked by GSI (Fig. S5 A and B). In contrast, Snail-1 mRNA levels, which were augmented by hypoxia, were reduced by GSI but not by BAPN treatment (Fig. S5C). Collectively, these data show that hypoxia-induced transcription of Snail-1 depends on functional Notch signaling but not on LOX but that LOX exerts an effect on Snail-1 protein stability. This indicates that Notch signaling indirectly potentiates LOX expression in a hypoxia-dependent manner, which is manifested by elevated Snail-1 protein levels in response to combined hypoxia and Notch signaling.

Hypoxia-Induced Cell Motility and Invasiveness Require Notch Signaling.

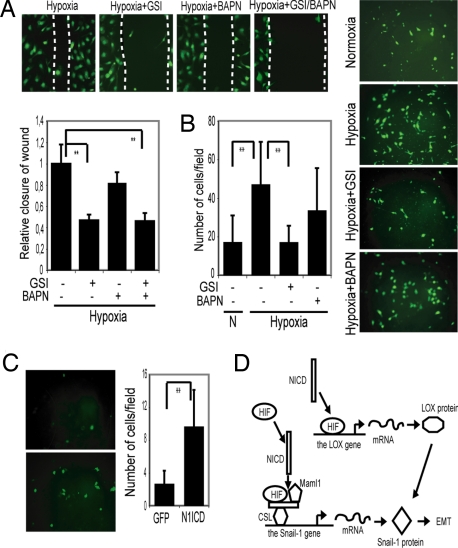

Increased cell motility and invasiveness are important consequences of hypoxia-induced EMT (5). To study cell motility, we used a scratch wound-healing assay, where the extent of migration of cells into the scratched area was measured. Migration of SKOV-3 cells was elevated during hypoxia but effectively blocked in the presence of GSI (Fig. 6A). To address the relationship between Notch and LOX in this context, we used BAPN and GSI to block LOX and Notch signaling, respectively. The addition of BAPN reduced migration, but less effectively than GSI, and the combined use of BAPN and GSI did not block migration to a higher extent than GSI treatment alone (Fig. 6A). Conversely, activation of Notch signaling by exposure to immobilized ligand increased motility in the wound scratch assay (Fig. S6A).

Fig. 6.

Notch signaling is required for migration and invasiveness of SKOV-3 cells. (A) Scratch wound healing assay of fluorescently labeled SKOV-3 cells cultured at hypoxia and treated with GSI, BAPN, or GSI + BAPN. Quantification of relative closure of the scratch wound compared with the control. The graph shown below represents the results of three separate experiments each performed in triplicates, where the distance of the wound is measured at four to six reference points along the scratch wound. (B) Transmembrane invasion assay of fluorescently labeled SKOV-3 cells kept at normoxia or hypoxia in the absence or presence of GSI or BAPN. (C) Adenoviral infection of N1ICD-GFP or GFP into SKOV-3 cells kept at normoxia, Quantification of the number of invading cells per field. A minimum of six fields of three separate wells within each experiment were analyzed. The graphs represent data from three (B) and two (C) separate experiments. (D) Model for how Notch controls Snail-1 at two different levels. N1ICD is recruited to the Snail-1 promoter, and we propose that HIF1α is also part of the transcriptional complex (together with CSL and Maml1). For the LOX promoter, the binding of HIF1α is potentiated by N1ICD, but N1ICD does not bind directly to the transcriptional complex. Notch is thus proposed to control Snail-1 in two different but synergistic ways, leading to elevated Snail-1 transcription and stabilization of the resulting protein.

To study the invasive properties of the SKOV-3 cells, we used a Matrigel transmembrane invasion assay, where migration of cells across a membrane toward a source of serum attractant was monitored. Hypoxia induced an increase in invasiveness, which was substantially blocked by GSI (Fig. 6B) or by expression of dnMaml1 (Fig. S6B). In contrast, inhibition of LOX by BAPN was less effective (Fig. 6B). In a converse experiment, we tested the effects on invasiveness of up-regulating Notch in normoxia. Transient expression of N1ICD increased migration and invasiveness during normoxia (Fig. 6C) and could thus substitute for hypoxia. This demonstrates that pharmacological intervention with Notch signaling effectively reduces hypoxia-induced migration and invasion capacity.

Conclusions

This article provides evidence for a hypoxia/Notch/EMT axis in tumor cells, and in this process, Notch regulates Snail-1 levels in two different but synergistic ways. The regulation of Snail-1 and LOX expression also sheds light on how the Notch and hypoxia signaling mechanisms are integrated and how Notch ICD and HIF-1α cooperate but take on different roles on the two promoters, as schematically depicted in Fig. 6D. The role of Notch as a mediator of the hypoxic stimulus into enhanced cell migration and invasiveness opens perspectives for intervention. In keeping with this notion, a recent report shows that Notch controls expression of Slug (Snail-2) and that block of Notch signaling inhibits tumor growth and metastasis in an in vivo tumor model (35). Refinement of Notch inhibitors combined with more local containment, e.g., in epithelial tumors at risk for metastasizing, may therefore be a productive way toward improving cancer therapy.

Materials and Methods

Details for plasmid constructs, cell culture, Notch activity assay, RNA extraction and quantitative RT-PCR, immunocytochemistry and Western blot analysis, cell migration and invasion, activation of Notch signaling using immobilized recombinant Notch ligands, transfections and viral infections, and chromatin immunoprecipitation are given in SI Experimental Procedures.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We are grateful to Drs. W. Pear (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia) and M. A. Nieto (Instituto de Neurosciencias de Alicante, Elche, Spain) for the dominant-negative MAML1 and Snail-1 promoter–reporter, respectively, and to Susanne Bergstedt for cell culture work. This work was supported by the Swedish Cancer Society, the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research, the European Union project EuroStemCell (U.L.), and the Juselius Foundation and Academy of Finland (C.S.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0802047105/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Schindl M, et al. Overexpression of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α is associated with an unfavorable prognosis in lymph node-positive breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:1831–1837. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhong H, et al. Overexpression of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α in common human cancers and their metastases. Cancer Res. 1999;59:5830–5835. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gordan JD, Simon MC. Hypoxia-inducible factors: Central regulators of the tumor phenotype. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2007;17:71–77. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keith B, Simon MC. Hypoxia-inducible factors, stem cells, and cancer. Cell. 2007;129:465–472. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Christofori G. New signals from the invasive front. Nature. 2006;441:444–450. doi: 10.1038/nature04872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee JM, Dedhar S, Kalluri R, Thompson EW. The epithelial–mesenchymal transition: New insights in signaling, development, and disease. J Cell Biol. 2006;172:973–981. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200601018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huber MA, Kraut N, Beug H. Molecular requirements for epithelial–mesenchymal transition during tumor progression. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005;17:548–558. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cavallaro U, Christofori G. Cell adhesion and signalling by cadherins and Ig-CAMs in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:118–132. doi: 10.1038/nrc1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Batlle E, et al. The transcription factor snail is a repressor of E-cadherin gene expression in epithelial tumour cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:84–89. doi: 10.1038/35000034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barrallo-Gimeno A, Nieto MA. The Snail genes as inducers of cell movement and survival: Implications in development and cancer. Development. 2005;132:3151–3161. doi: 10.1242/dev.01907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perl AK, Wilgenbus P, Dahl U, Semb H, Christofori G. A causal role for E-cadherin in the transition from adenoma to carcinoma. Nature. 1998;392:190–193. doi: 10.1038/32433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moody SE, et al. The transcriptional repressor Snail promotes mammary tumor recurrence. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:197–209. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ivan M, et al. HIFα targeted for VHL-mediated destruction by proline hydroxylation: Implications for O2 sensing. Science. 2001;292:464–468. doi: 10.1126/science.1059817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jaakkola P, et al. Targeting of HIF-α to the von Hippel–Lindau ubiquitylation complex by O2-regulated prolyl hydroxylation. Science. 2001;292:468–472. doi: 10.1126/science.1059796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Semenza GL. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1: Oxygen homeostasis and disease pathophysiology. Trends Mol Med. 2001;7:345–350. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4914(01)02090-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bruick RK. Oxygen sensing in the hypoxic response pathway: Regulation of the hypoxia-inducible transcription factor. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2614–2623. doi: 10.1101/gad.1145503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bardos JI, Ashcroft M. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 and oncogenic signalling. BioEssays. 2004;26:262–269. doi: 10.1002/bies.20002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gustafsson MV, et al. Hypoxia requires Notch signaling to maintain the undifferentiated cell state. Dev Cell. 2005;9:617–628. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Timmerman LA, et al. Notch promotes epithelial–mesenchymal transition during cardiac development and oncogenic transformation. Genes Dev. 2004;18:99–115. doi: 10.1101/gad.276304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zavadil J, Cermak L, Soto-Nieves N, Bottinger EP. Integration of TGF-β/Smad and Jagged1/Notch signalling in epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. EMBO J. 2004;23:1155–1165. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weng AP, et al. Activating mutations of NOTCH1 in human T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Science. 2004;306:269–271. doi: 10.1126/science.1102160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pece S, et al. Loss of negative regulation by Numb over Notch is relevant to human breast carcinogenesis. J Cell Biol. 2004;167:215–221. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200406140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stylianou S, Clarke RB, Brennan K. Aberrant activation of Notch signaling in human breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:1517–1525. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kadesch T. Notch signaling: The demise of elegant simplicity. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2004;14:506–512. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilson A, Radtke F. Multiple functions of Notch signaling in self-renewing organs and cancer. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:2860–2868. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chapman G, Liu L, Sahlgren C, Dahlqvist C, Lendahl U. High levels of Notch signaling down-regulate Numb and Numblike. J Cell Biol. 2006;175:535–540. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200602009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Imai T, et al. Hypoxia attenuates the expression of E-cadherin via up-regulation of SNAIL in ovarian carcinoma cells. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:1437–1447. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63501-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barrick D, Kopan R. The Notch transcription activation complex makes its move. Cell. 2006;124:883–885. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ong CT, et al. Target selectivity of vertebrate notch proteins. Collaboration between discrete domains and CSL-binding site architecture determines activation probability. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:5106–5119. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506108200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kopan R, Schroeter EH, Weintraub H, Nye JS. Signal transduction by activated mNotch: Importance of proteolytic processing and its regulation by the extracellular domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:1683–1688. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.4.1683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Evans AJ, et al. VHL promotes E2 box-dependent E-cadherin transcription by HIF-mediated regulation of SIP1 and snail. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:157–169. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00892-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Erler JT, et al. Lysyl oxidase is essential for hypoxia-induced metastasis. Nature. 2006;440:1222–1226. doi: 10.1038/nature04695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peinado H, Portillo F, Cano A. Switching on-off Snail: LOXL2 versus GSK3β. Cell Cycle. 2005;4:1749–1752. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.12.2224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peinado H, et al. A molecular role for lysyl oxidase-like 2 enzyme in snail regulation and tumor progression. EMBO J. 2005;24:3446–3458. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leong KG, et al. Jagged1-mediated Notch activation induces epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition through Slug-induced repression of E-cadherin. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2935–2948. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jarriault S, et al. Signalling downstream of activated mammalian Notch. Nature. 1995;377:355–358. doi: 10.1038/377355a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kato H, et al. Involvement of RBP-J in biological functions of mouse Notch1 and its derivatives. Development. 1997;124:4133–4141. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.20.4133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weng AP, et al. Growth suppression of pre-T acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells by inhibition of Notch signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:655–664. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.2.655-664.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chung CN, Hamaguchi Y, Honjo T, Kawaichi M. Site-directed mutagenesis study on DNA binding regions of the mouse homologue of Suppressor of Hairless, RBP-J kappa. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:2938–2944. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.15.2938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barbera MJ, et al. Regulation of Snail transcription during epithelial to mesenchymal transition of tumor cells. Oncogene. 2004;23:7345–7354. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Masson N, Willam C, Maxwell PH, Pugh CW, Ratcliffe PJ. Independent function of two destruction domains in hypoxia-inducible factor-alpha chains activated by prolyl hydroxylation. EMBO J. 2001;20:5197–5206. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.18.5197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.