Abstract

The original Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain (SOAPP) is a conceptually derived self-report questionnaire designed to predict aberrant medication-related behaviors among chronic pain patients considered for long-term opioid therapy. The purpose of this study was to develop and validate an empirically-derived version of the SOAPP (SOAPP-R) that addresses some limitations of the original SOAPP. In successive steps, items were reduced from an initial pool of 142 to a 97-item beta version. The beta version was administered to 283 chronic pain patients on long-term opioid therapy. Items were evaluated based on data collected at follow-up, including correlation with the Aberrant Drug Behavior Index (ADBI), derived from interview data, physician ratings, and urine toxicology screens. Twenty-four items were retained and comprise the final SOAPP-R. Coefficient α was .88, and receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve analysis yielded an area under the curve (AUC) of .81 (p < .001). A cutoff score of 18 showed adequate sensitivity (.81) and specificity (.68). The obtained psychometrics, along with the use of a predictive criterion that goes beyond self-report, suggest that the SOAPP-R is an improvement over the original version in screening risk potential for aberrant medication-related behavior among persons with chronic pain.

Perspective:

There is need for a screener for abuse risk in patients prescribed opioids for pain. This study presents a revised version of the Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain (SOAPP-R) that is empirically-derived with good reliability and validity, but is less susceptible to overt deception then the original SOAPP v.1.

Keywords: substance abuse, chronic pain, opioids, addiction, aberrant drug behaviors

Introduction

There has been a growing use of opioids for the treatment of chronic pain, especially for chronic noncancer pain.14 The prevalence of addiction to any substance in a pain population has been estimated to be around 10%.11, 27,39 and increasing notice has been given to the abuse of prescription opioid medication.18 Many physicians prescribing pain medication have little training in addiction or in dealing with aberrant medication-related behavior.37 These physicians prescribe opioids for patients with chronic pain without an indication of the level of risk for medication abuse.4 While substance abuse is prominent in the chronic pain population, the potential for inadequate treatment of pain may be greater for patients with a history of substance abuse due, in part, to a general reluctance to address substance abuse issues.17,21 In a survey of primary care physicians, a third of responders indicated that they would not under any circumstance prescribe opioids to patients with chronic noncancer pain.23,28 Seventy percent of these same physicians indicated that noncancer chronic pain is usually inadequately treated.23,28 Thus, opioids can be an effective treatment for chronic pain, yet providers are reluctant to prescribe opioids because of concerns over tolerance, dependence, and addiction.37,39 Optimal use of opioids must include an evaluation of risk associated with potential abuse of opioid medication.4,39

The 14-item SOAPP (Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain, referred to in this article as SOAPP v.1 for clarity) was created to identify which chronic pain patients may be at risk for problems with long-term opioid medication.6 An expert panel of pain and addiction experts was asked to identify and rate risk factors of potential problems with opioids in patients considered for opioid therapy resulting in eight conceptual clusters of risk factors.35

These results were used to construct the 24-item SOAPP v.1, which was administered to 175 patients taking opioids for chronic pain. These patients were followed for six months and evaluated for aberrant medication-related behavior based on an interview.10 Of the original 24 items, 14 items appeared to predict subsequent self-report of aberrant behaviors. A second study found that patients who scored above the cutoff on the SOAPP v.1 (i.e., were high risk for misuse of their opioid medication) were younger, more likely to be asked to give a urine screen, and had more abnormal urine screens compared with those whose SOAPP v.1 scores placed them in the low risk group (p<0.05).1

The original SOAPP v.1 was considered an initial step toward development of a screener for aberrant medication-related behaviors in chronic pain patients. This scale was conceptually derived, rather than undergoing empirical item-selection. Furthermore, several items required patients to admit to a number of incriminating behaviors. Perhaps most problematic, predictive validity of the SOAPP v.1 was tested primarily against self-reported aberrant behaviors at follow-up. It is possible, therefore, that the observed correspondence between the SOAPP v.1 and subsequently reported behaviors was artificially enhanced since people who self-disclose problematic behaviors in a baseline assessment may be the same ones who self-disclose these behaviors at follow-up. When developing a revised version of the SOAPP v.1, we hoped to address this deficiency by systematically integrating self-report with provider observations and toxicology results. Thus, the purpose of this study was to develop and validate a revised version of the SOAPP v.1 (SOAPP-R) based on empirically-derived items that could address some limitations of the SOAPP v.1.

Methods

Concise definitions of terms are important to minimize confusion and help to clarify the objectives of this study. For purposes of this study, substance misuse is defined as the use of any drug in a manner other than how it is indicated or prescribed. Substance abuse is defined as the use of any substance when such use is unlawful, or when such use is detrimental to the user or others. Addiction is a primary, chronic, neurobiological disease characterized by behaviors that include one of more of the following: impaired control over use, compulsive use, continued use despite harm, and craving.2 Aberrant drug-related behaviors are any behaviors that imply misuse of prescription medications.7,33 All these negative consequences from using opioids are relevant concerns to the treating physician. Thus, the intent of the SOAPP-R was to identify chronic pain patients who are being considered for long-term opioid therapy and who may be either at high or low risk for having trouble with their medication (i.e., future misuse and/or abuse of opioids).

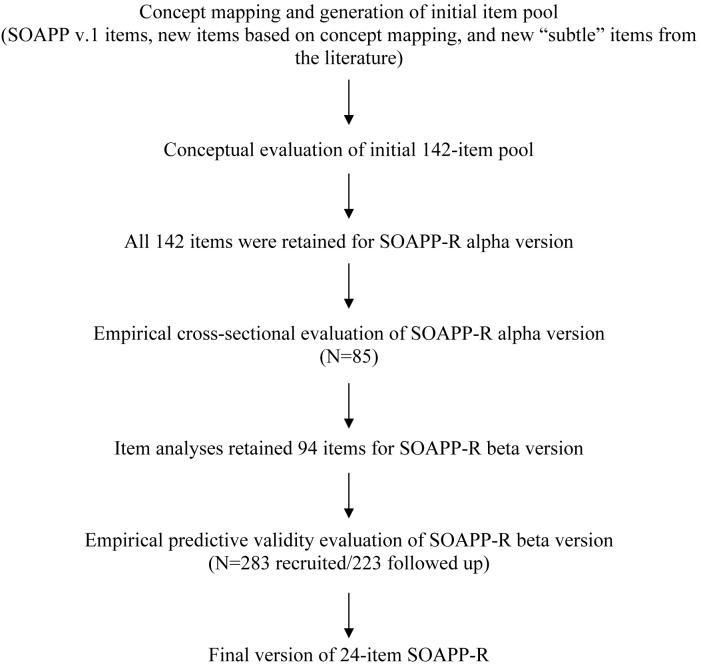

The SOAPP-R was developed and validated in a series of steps, starting with the creation of an item pool, and then successively testing and eliminating items, leaving only those items with the best balance of psychometric features. First, an item pool was created and items conceptually evaluated, resulting in an alpha version of the scale. Second, items in the alpha version were empirically evaluated and surviving items became the beta version. Lastly, empirical evaluation of the beta version resulted in a final version of the SOAPP-R. For the sake of clarity, the steps in the scale development process are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Steps in the Scale Development Process

Creation of an Item Pool

Since the SOAPP v.1 was created using items identified as conceptually predictive, we sought to improve upon this work by creating a large pool of items that would be included to see what empirical relationship might be achieved in prospective testing of the items. Many of these items were expected to “fall out” during later testing. Toward this end, we returned to the original effort to establish content validity for the SOAPP v.1. In that study, a consensus of pain and addiction experts was sought to determine those patient characteristics and circumstances judged to be predictive of aberrant drug-related behaviors. To accomplish this, the experts participated in an exercise called concept mapping. Concept mapping14,34,35 is a qualitative and quantitative process that enables researchers to capture a group's consensus about a problem or issue. The process is inductive (bottom–up) in that it begins with brainstorming specific ideas stimulated by a focus instruction or prompt and moves, step-by-step, toward more general concepts. Results of the original concept mapping process resulted in an eight-cluster solution, identifying the following concepts: antisocial behaviors/history, substance abuse history, medication-related behaviors, doctor-patient relationship factors, psychiatric history, emotional attachment to pain medications, personal care and lifestyle issues, and finally, psychosocial problems. The concept mapping information was used by the research team to construct the initial pool of items representing each of the eight identified concepts. Specific procedures and results, including the concept maps, are presented in detail elsewhere.6

Thus, using this prior conceptual work as a starting point, the research team created a pool of potential items for the alpha version of the SOAPP-R that included the original SOAPP v.1 items (derived from the concept mapping results), new items generated from the concept mapping results, and additional items based on a review of the literature of possible “subtle” or sensitive items related to substance abuse. With regard to these subtle or sensitive items, we were interested in including items that would correlate with substance abuse but would be less transparent to respondents as to which way the item might be scored. We performed a search of articles on Medline using the key words ‘substance abuse’ and ‘addiction.’ Impulsivity15, anger24, resentment13, and boredom29 were identified in the literature as traits of persons who use illicit substances and are potentially prone to addiction. Additional concepts were considered at this early stage of item development since many items could be tested. Those that were not predictive would fall out during the successive stages of item testing. The main concern at this stage was to include any possible item that might be predictive. This was especially true for possible “subtle” items. Furthermore, it was expected that so-called “subtle” items would also be items that have high sensitivity so that more individuals would be likely to endorse these items. Thus, items were considered subtle when their relationship to the outcome (i.e., medication misuse) was not immediately obvious to the patient, but the item correlated with the target condition. One might expect a higher number of false positives on such items than on specific items (which tend to be answered by fewer individuals).22 Screening measures should have both sensitive and specific items. Furthermore, items were worded in a way to implicitly normalize or assume necessity of some aberrant behavior. Pain experts have proposed that such normalization may help people decide to admit to problematic behaviors.32

Conceptual Evaluation and Creation of an Alpha Version of the SOAPP-R

Conceptual evaluation involved having pain and addiction experts and patients give feedback on specific features and qualities of the items. Pain management and addiction specialists and chronic pain patients who had been on opioid medication for at least six months were asked to review the list of items and rate each of the statements on “Importance” and “Quality of Wording,” on a scale from 1 “not at all important/very poor wording,” to 5 “very important/excellent wording.” For quality, raters were asked to consider the following characteristics: (1) The item should not be offensive or potentially biased with respect to any gender, ethnic, economic, religious, or other group. (2) The item should be worded unambiguously, at a sixth grade level. Items should have no more than 10 words whenever possible. No double negatives should be used and single negatives should be avoided if possible. (3) Colloquialisms or slang should be avoided, to prevent items from becoming dated within a few years. (4) The meaning of an item should be clear and readily apparent (i.e., the item should not be confusing). Finally, when making ratings of importance, the experts were instructed to consider the items broadly so as to include sensitive or subtle items. Expert ratings were augmented by a separate set of ratings made by the research team. All ratings were included in the selection of alpha items. Statements that achieved an average importance or quality rating of less than 3 were to be excluded or revised. This process resulted in the alpha version of the SOAPP-R.

Empirical Evaluation of the Alpha Version of the SOAPP-R

Empirical evaluation of alpha version items entailed examination of the following parameters: (1) Item distribution; (2) Item sensitivity to social desirability; (3) Item consistency; (4) Item bias with respect to gender, age (young versus older patients), ethnicity, and substance abuse history; (5) Test-retest reliability of items; and (6) Item validity in terms of positive, cross-sectional correlations with a measure of aberrant drug-related behavior variable, called the Aberrant Drug Behavior Index (the criterion). Although predictive validity is the ultimate aim of the SOAPP-R, this initial item evaluation utilized a cross-sectional approach.3

Participants

Eighty (N = 85) patients were recruited from an urban-based pain clinic in the Boston area. Patients were in treatment for chronic noncancer pain and on a long-term opioid treatment regimen for their pain.

Patient Completed Measures

In addition to the alpha version of the SOAPP-R, participants completed the following questionnaires: (1) a Demographic Questionnaire; (2) the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI)9; (3) the short form of the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale30; and (4) the Short-Form-36 (SF-36). The SF-36 measures the health status of medical and psychiatric patients, has been extensively researched36 and has good reliability (internal consistency range from .73 to .96; test-retest from .60 to .81) and validity (correlations > .40 with other measures of general health and functioning).

Patient Interview Measure

Self-report of patient status was obtained using the Prescription Drug Use Questionnaire (PDUQ).810 This 42-item interview is an acceptable abuse/misuse assessment screener for pain patients.32 Based on the American Society of Addiction Medicine's (ASAM) definition of addiction in chronic pain patients, the PDUQ is a 20-minute interview where the patient is asked about his or her pain condition, opioid use patterns, social and family factors, family history of pain and substance abuse syndromes, patient history of substance abuse, and psychiatric history. The PDUQ has been shown to distinguish addicted and non-addicted patients using modified DSM-IV criteria such that subjects scoring below 11 “did not meet criteria for a substance disorder” and those scoring 15 or greater “had a substance use disorder.” For purposes of this study, patients with a score of 11 or higher on the PDUQ interview were identified as being at risk for a substance disorder. The interview was administered by a trained research assistant (RA) identified at each performance site.

Procedures

Patients were identified by clinic staff to the RA as having been prescribed opioid medication for chronic noncancer pain. Patients completed the self-report, pencil-and-paper measures, including the alpha version of the SOAPP-R. The RA then conducted the semi-structured interview PDUQ. To examine test-retest, 50 patients were randomly identified from the 85 to complete the SOAPP-R items again in three days. These patients were given a package containing the second SOAPP-R. They were called three days later and reminded to complete the form and return it in a self-addressed, stamped envelope.

Selection of Items

Selection of items for the beta version was made by the research team. Those items with the best balance with respect to the parameters outlined above were selected. Items were considered with regard to 1) item distribution, 2) item consistency, 3) social desirability, 4) demographic bias, 5) test-retest reliability, and 6) concurrent validity. Items with good characteristics on a number of the parameters but with one or two specific problems were retained for further examination in a prospective examination of predictive validity. Items that otherwise looked good on the parameters were excluded based on redundancy of content. Achieving a balance of these parameters followed a step-by-step process outlined in detail in the Results section below. Finally, reading level of the retained items was tested using the Flesch-Kincaid rating scale. Items that were at a reading level greater than 6th grade were excluded.

Evaluations of the Beta Version of the SOAPP-R and creation of the Final Version

In this stage, patients with chronic pain on long-term opioid regimens were recruited to complete the beta version of the SOAPP-R and followed for five months. At follow-up, patient status with respect to aberrant medication related behaviors was evaluated based on a combination of self-reported behaviors, physician observations, and urine toxicology results. A subset of these patients was randomly selected to complete a second administration of the SOAPP-R one week later.

Participants

Two-hundred-eighty-three (N = 283) patients were recruited from pain clinics in the Boston area, Pennsylvania, and Ohio. All patients were in treatment for chronic noncancer pain and on a long-term opioid treatment regimen for their pain.

Patient Completed Measures

The same self-report measures used to evaluate the alpha version items were administered to this cohort of patients. In addition, at follow-up, patients completed the self-report interview PDUQ, described above.

Physician Completed Measure

Each patient's physician was asked to complete the Prescription Opioid Therapy Questionnaire (POTQ).21 This 11-item scale, adapted from the Physician Questionnaire of Aberrant Drug Behavior, was completed by the treating clinician to assess misuse of opioids. The items reflect the behaviors outlined by Chabel et al.8 that were indicative of substance abuse. The participant patient's chart was made available to the treating physician to facilitate accurate recall of information. Providers answered yes or no to eleven questions indicative of misuse of opioids, including multiple unsanctioned dose escalations, episodes of lost or stolen prescriptions, frequent unscheduled visits to the pain center or emergency room, excessive phone calls, and inflexibility around treatment options. Patients who were positively rated on two or more of the items met criteria for prescription opioid misuse.

Toxicology Screen

Participating patients were requested to provide a urine sample during their follow-up visit and to inform staff of their current medications. Patients were informed that information from the toxicology screen would remain confidential and not be part of their medical record. Each patient was given a specimen cup and instructed to provide a urine sample (∼30 −75 ml of urine) without supervision in the clinic bathroom. The RA at each center collected and shipped the sample to a central Quest Diagnostics lab (www.questdiagnostics.com). The results of the urine toxicology were sent directly to the research team. The treating physician and the clinic did not have access to the results. The report included evidence of 6-MAM (heroin), codeine, dihydrocodeine, morphine, oxycodone, oxymorphone, hydrocodone, hydromorphone, meperidine, methadone, propoxyphene, buprenorphine, fentanyl, tramadol, amphetamines, barbiturates, benzodiazepines, cannabinoids, cocaine, phencyclidine, and ethyl alcohol.

Creation of the Aberrant Drug Behavior Index (ADBI)

Patients were classified as to whether they engaged in aberrant medication-related behavior. Aberrant medication use incorporates a variety of behaviors commonly believed to be associated with opioid medication misuse, abuse, and addiction.33 Since there is no gold standard for identifying which patients are and which are not abusing their prescription medications,32 we classified patients into categories of aberrant medication-related behavior by triangulating three perspectives, self-report via structured interview, physician report, and urine toxicology results. The ADBI is based on positive scores on 1) the self-reported PDUQ, 2) the physician-reported POTQ, and 3) the urine toxicology results. A positive rating on the PDUQ is an accumulated score higher than 11. A positive rating on the POTQ is given to anyone who has two or more physician-rated aberrant behaviors.6 A positive rating from the urine screens is given to anyone with evidence of having taken an illicit substance (e.g., cocaine) or an additional opioid medication that was not prescribed. We chose not to count the omission of a prescribed opioid medication from the urine screen results as a positive rating because of multiple factors that can contribute to this result (e.g., subject ran out the medication before the urine screen). We also did not classify urines that were rejected by the lab. Urine screen results were confirmed based on chart review of prescription history and a comparison between self-report at the time of the urine screen and the toxicology report. Those with positive scores on the PDUQ were given a positive ADBI. If this score was negative, then positive scores on both the urine toxicology screen and on the POTQ (≥2) contributed to a positive ADBI. This allowed for triangulation of data to identify those patients who admitted to aberrant medication-related behavior and those who underreported aberrant behavior (e.g., low PDUQ scores, but positive POTQ and abnormal urine screen results). For those patients who did not have results of urine toxicology screens, ADBI classification was based on results of the PDUQ and POTQ.

Procedures

Patients who had been prescribed opioid medication for chronic noncancer pain either responded to a posted notice or were invited by their treating physician to participate in this study. Patients completed the self-report, pencil-and-paper measures, including the beta version of the SOAPP-R. At follow-up, a researcher conducted the semi-structured interview PDUQ and collected the urine specimen. To examine test-retest reliability, 55 patients were randomly identified from the 283 to complete the SOAPP-R items again one week later. Procedures were the same as for the alpha version test. Physicians were contacted by research staff at the follow-up period and asked to complete the POTQ.

Final Selection of Items

Final selection of items was made by the research team. Again, the best balance with respect to the parameters at the item level was sought when making the final selection.

Patient participants

The Humans Subjects Committee of each of the hospitals approved this study's procedures. Chronic noncancer pain patients were recruited from pain management centers in three states (Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, and Ohio). Patients prescribed opioids for their pain were informed about the study and invited to participate. All subjects signed an informed consent form and were assured that the information obtained through questionnaire responses or urine toxicology results would remain confidential and would not become part of their clinic record. Participant patients were paid with a $50 check or gift certificate for completing the initial measures and a $100 check or gift certificate for completing the follow-up measures.

A randomly selected group of patients were asked to complete the beta version of the SOAPP-R to determine test-retest reliability. These subjects took a copy of the questionnaire home and were instructed to complete the SOAPP-R one week later and to mail their completed questionnaire in a self-addressed mail envelope. Those subjects who completed the one-week re-test were given a $75 gift certificate.

Statistical analyses

All data were analyzed with SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences; Chicago, IL) v.13.0. Relations among demographic data, interview items, and questionnaire data were analyzed using Pearson Product Moment or IntraClass correlations, t-tests, computations of coefficient alpha, and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis as appropriate. ROC curve analyses were used to assess the sensitivity and specificity of the SOAPP-R as a screening tool for the detection of aberrant medication-related behavior.

Results

Creation of an Item Pool

Creation of the original item pool was formed by a consensus of 26 experts on predictive indicators or risk factors of potential problems with opioids in patients considered for opioid therapy. Methods and results of the concept mapping portion of this study have been described in detail previously.6 The panel of experts included pain specialists, primary care providers who treat patients with pain, nurses, and support staff at pain treatment centers. The concept mapping procedures identified eight domains that items should cover, including antisocial behaviors/history, substance abuse history, medication-related behaviors, doctor-patient relationship factors, psychiatric history, emotional attachment to pain medications, personal care and lifestyle issues, and finally, psychosocial problems. The concept mapping information was used by the research team to construct 142 items that represented each of these constructs.

Conceptual Evaluation and Creation of an Alpha Version of the SOAPP-R

All 142 items were submitted to a group of experts and chronic pain patients to be evaluated conceptually. Fourteen professionals and thirteen patients evaluated the items (N=27). Among the professionals, six (46%) were doctoral-level providers/experts (five MDs and one Ph.D.), and the remaining 54% were nursing staff. The results of this evaluation revealed average item ratings ranging from 4.07 to 1.86. Although the experts were instructed to consider the items broadly so as to include sensitive or subtle items, when reviewing the results, we became concerned that the experts instead rated items poorly that were not, in their view, obviously related to abuse or misuse of opioids. This, in turn, could result in many potentially sensitive and subtle items being rated more poorly. Items rated lower than a ‘3’ on the 1 to 5-point scale were reviewed by the team and, where appropriate, reworded or simplified. Since the value of potentially subtle or sensitive items might only become clear upon empirical testing, all 142 statements were retained in the alpha version of the SOAPP.

Empirical Evaluation of the Alpha Version of the SOAPP-R

Of the 85 patients recruited from an urban pain treatment center, 47% were men and 53% were women. Average age was 48.8 years (SD = 11.44, range 22-84, median = 47), and 77% were Caucasian, with 10% African American, 5% Hispanic, 5% Native American, and 3% Asian or other. Most (85%) had at least a high school education and most were quite disabled. Only 16.5% were currently working and 41% were on disability. Average length of chronic pain was 6.2 years (SD= 6.5 years; range = 7 months to 45 years). Per protocol, all patients had been prescribed opioid medication for chronic pain for at least six months. Responses to the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) revealed that 92% reported being in pain “today.” On a pain rating scale from 0 (least) to 10 (worst), the pain “on average” was 5.9 (SD=2.0) and the pain “right now” was 5.8 (SD = 2.7).

Results of the Empirical Evaluation of the Alpha Version

The purpose of this initial empirical test was to eliminate some items based on their performance on important psychometric parameters. All patients included at this stage had been prescribed a long-term opioid regimen for least six months, permitting cross-sectional analyses of the items' relationship with an independent measure of patient medication misuse. This cross-sectional analysis was not a test of the predictive validity of the items, which occurred later in the scale development process.

Final items selected attempted to achieve a balance with respect to performance on all the parameters. The first parameter we examined was item distribution. For “specific” items (i.e., items contributing to a scale's specificity), one expects low levels of endorsement (i.e., restricted range and/or relatively low mean rating). In this analysis, we used the rough standard of a mean between 0 and 1 and item content to identify 50 items as potential contributors to specificity (high number of valid negatives) and 43 items with higher means and greater number of valid positive as potentially “sensitive” items (i.e., items contributing to the sensitivity of the scale). Next, item consistency was examined to maximize the efficiency of the scale using corrected-item total correlation (sometimes called the part-whole correlation). In general, items with corrected-item total correlations lower than .20 were excluded. Next, item social desirability was examined to ensure that an item's correlation with the Marlowe-Crowne was lower than the item's correlation with the criterion variable. The items were also subjected to a set of analyses to highlight those that may be biased for race, age, gender, or presence of substance abuse history. The bias examination is important to ensure that the meaning of selected items is the same across race, age, history, or substance abuse history. Substance abuse history was included to avoid a bias in items for patients with such a history. Linear regression techniques were used to equate slopes and intercept parameters of items regressed upon the external criteria. In general, the items did not show much bias and no item was discarded at this stage based on this parameter alone. For the test-retest analysis, 50 patients were randomly selected to receive a second administration of the alpha version of the SOAPP three days later. Of the 50 patients selected for this study, 49 (98%) were successfully followed. The resulting correlations between administrations suggest that virtually all the items had good test-retest reliability in excess of our target of .50. Finally, concurrent validity was examined to get an estimate of predictive validity.3 A cross-sectional analysis was used to examine the correlation between each item and the PDUQ score. Most items correlated between .68 and .20 with the criterion.

As noted, no single parameter was used to exclude an item. Ninety-four (94) items from the pool of 142 survived this evaluation to comprise the beta version of the SOAPP-R. A final test of reading level was conducted on these items, which yielded a Flesch-Kincaid rating of grade 5.3, which met our goal of a 6th grade reading level.

Evaluations of the Beta Version of the SOAPP-R and creation of the Final Version

For the analyses of the beta version of SOAPP-R, 283 patients who were taking long-term opioid medication for chronic noncancer pain participated in this stage of the study (Table 1). The average age of the patients was 49.8 years, 44.4% were women, 85.1% Caucasian, and 66.8% reported low back pain as their primary pain site. The patients were prescribed immediate-release (53.6% oxycodone with acetaminophen; 15.5% hydrocodone; 9.5% oxycodone; 7.2% morphine; 7.1% hydromorphone; 3.6% codeine; 3.6% propoxyphene), and sustained-release (43.3% oxycodone; 22.7% methadone; 20.6% transdermal fentanyl; 13.4% morphine) opioids for pain. Twenty-seven percent were taking both long and short-acting opioids for pain. Sixty patients were selected to complete the beta version of the SOAPP-R 1-week later for a retest and 54 (90%) successfully returned the completed questionnaire. Average age for these patients was 48.6 years (SD = 9.8; range 29 to 81), 47.2% were women, 81.1% were Caucasian, and 73.6% identified having low back pain. Of the 283 patients, 223 (79%) were successfully followed and provided enough data to establish the predictive criterion (the ADBI score). While those who could not be followed did not differ from completers with respect to gender, marital status, and education level, there were significant differences with respect to age (mean completer's age = 50.5, SD = 12.8; mean non-completer's age = 46.3, SD = 11.7, t = 2.27, df = 278, p = .024) and minority status (i.e., Caucasian versus minority, χ2 = 4.7, df = 1, p = .031).

Table 1.

Patient demographic and descriptive characteristics (N=283).

| Variable | |

|---|---|

| Age | 49.8 (±12.8; range 21-89) |

| Gender (% female) | 60.8 |

| Married (% yes) | 44.4 |

| Race (% Caucasian) | 85.1 |

| High school graduate (% yes) | 87.3 |

| Pain site (% low back) | 66.8 |

| Yrs taking opioids | 5.9 (±10.5; range 5 mos to 77 yrs) |

| Pain:† Worst (24 hrs; 0-10) | 7.2 (±2.1; range 0-10 |

| Least (24 hrs; 0-10) | 4.4 (±2.2; range 0-10) |

| Average (24 hrs; 0-10) | 6.0 (±1.8; range 0-10) |

| Now (0-10) | 5.8 (±2.2; range 0-10) |

| Pain relief from meds* (0-10) | 6.3 (±2.2; range 0-10) |

| Pain interference with:‡ | |

| General activity | 6.4 (±2.6; range 0-10) |

| Mood | 5.0 (±2.8; range 0-10) |

| Walking | 6.1 (±3.0; range 0-10) |

| Normal work | 7.1 (±2.6; range 0-10) |

| Relations with others | 4.0 (±3.1; range 0-10) |

| Sleep | 6.4 (±3.1; range 0-10) |

| Enjoyment of life | 6.2 (±3.0; range 0-10) |

| Marlowe-Crowne Score | 8.6 (±2.7; range 0-13) |

0=no pain; 10=pain as bad as you can imagine

0=no relief; 10=complete relief

0=does not interfere; 10=completely interferes

The results of 194 urine toxicology screens were entered into the database as an indicator for Aberrant Drug Behavior Index. Ninety subjects (31.7%) did not have toxicology results either because the patients could not come to the pain center or the sample could not be adequately analyzed. Thirty four percent of the subjects (N=97) had negative urines, 21.8% (N=62) were positive for a non-prescribed opioid, 1.8% (N=5) had cocaine or heroin detected in their urine, 6.0% (N=17) did not show any opioids in their urine, and for 4.6% (N=13) the urine sample could not be adequately analyzed either due to leakage or mislabeling.

Two hundred and twenty-three subjects (79%) successfully completed the PDUQ. The mean score was 8.89 (SD=4.53; range 1-28). Using the conservative cutoff score of >10 (Compton et al., 1998), 66 of the subjects (29.6%) were positive while 157 (70.4%) were negative. Physician ratings for followed patients were available for 93.7% of the patients (N=209) on the POTQ. The mean score for this scale was 2.49 (SD=1.43; range 0-9) and 47 (22.5% of all POTQ ratings) had positive ratings of >2. Using the algorithm for the ADBI, 77 (34.5%) were positive, 146 (65.5%) were negative. Only patients with an ADBI (N=223) were included in the ROC analyses for the SOAPP-R.

Results of the Empirical Evaluation of the Beta Version

To determine which items should be included in the SOAPP-R, each item was evaluated with respect to its content, contribution to coefficient alpha, range, test-retest performance, correlation with the ADBI, correlation with the Marlowe-Crowne, and effect size (Cohen's D) with the criterion. Twenty-four items were selected based on their having the best balance of these parameters in the estimation of the research team. Table 2 summarizes the psychometric parameters for the 24 items and the total score of the 24 items.

Table 2.

SOAPP-R items and psychometric values examined during item-selection.

|

SOAPP-R item (In the past 30 days,…) |

Included in original SOAPP |

Mean (SD) (N=283) Range (0 - 4) |

Test- Retest ICC (N = 54) |

Correlation with ADBI (N = 223) |

Correlation with Marlowe- Crowne (N = 268) |

Relation to Criterion Effect Size (Cohen's D) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. How often do you have mood swings? |

✓ | 2.01 (±1.09) (0 - 4) |

.66 | .24 | −.31 | .52 |

| 2. How often have you felt a need for higher doses of medication to treat your pain? |

1.64 (±1.06) (0 - 4) |

.67 |

.27 |

−.33 |

.58 |

|

| 3. How often have you felt impatient with your doctors? |

1.40 (±1.07) (0 – 4) |

.74 |

.20 |

−.17 |

.42 |

|

| 4. How often have you felt that things are just too overwhelming that you can't handle them? |

1.34 (±1.11) (0 – 4) |

.75 |

.34 |

−.32 |

.75 |

|

| 5. How often is there tension in the home? |

1.29 (±1.03) (0 – 4) |

.53 |

.33 |

−.26 |

.73 |

|

| 6. How often have you counted pain pills to see how many are remaining? |

1.10 (±1.05) 0 – 4) |

.69 |

.21 |

−.24 |

.45 |

|

| 7. How often have you been concerned that people will judge you for taking pain medication? |

1.14 (±1.02) (0 – 3) |

.51 |

.27 |

−.18 |

.58 |

|

| 8. How often do you feel bored? |

1.03 (±.92) (0 – 3) |

.63 |

.24 |

−.25 |

.52 |

|

| 9. How often have you taken more pain medication than you were supposed to? |

.81 (±.91) (0 – 4) |

.69 |

.41 |

−.16 |

.93 |

|

| 10. How often have you worried about being left alone? |

.81 (±1.08) (0 – 4) |

.78 |

.21 |

−.33 |

.43 |

|

| 11. How often have you felt a craving for medication? |

✓ |

.79 (±1.02) (0 – 4) |

.69 |

.33 |

−.16 |

.73 |

| 12. How often have others expressed concern over your use of medication? |

✓ |

.70 (±.91) (0 – 4) |

.61 |

.35 |

−.23 |

.77 |

| 13. How often have any of your close friends had a problem with alcohol or drugs? |

✓ |

.64 (±.91) (0 – 4) |

.66 |

.20 |

−.25 |

.43 |

| 14. How often have others told you that you had a bad temper? |

.66 (±.90) (0 – 4) |

.63 |

.20 |

−.34 |

.42 |

|

| 15. How often have you felt consumed by the need to get pain medication? |

.60 (±.90) (0 – 4) |

.71 |

.33 |

−.27 |

.73 |

|

| 16. How often have you run out of pain medication early? |

.59 (±.92) (0 – 4) |

.75 |

.39 |

−.14 |

.87 |

|

| 17. How often have others kept you from getting what you deserve? |

.49 (±.84) (0 – 4) |

.66 |

.23 |

−.30 |

.49 |

|

| 18. How often, in your lifetime, have you had legal problems or been arrested? |

✓ |

.38 (±.66) (0 – 4) |

.74 |

.23 |

−.10 |

.49 |

| 19. How often have you attended an AA or NA meeting? |

✓ |

.30 (±.75) (0 – 4) |

.92 |

.25 |

−.23 |

.55 |

| 20. How often have you been in an argument that was so out of control that someone got hurt? |

.28 (±.67) (0 – 4) |

.57 |

.22 |

−.23 |

.46 |

|

| 21. How often have you been sexually abused? |

.24 (±.71) (0 – 4) |

.89 |

.22 |

−.28 |

.48 |

|

| 22. How often have others suggested that you have a drug or alcohol problem? |

✓ |

.25 (±.58) (0 – 3) |

.66 |

.21 |

−.31 |

.45 |

| 23. How often have you had to borrow pain medications from your family or friends? |

.16 (±.52) (0 – 4) |

.68 |

.24 |

−.19 |

.52 |

|

| 24. How often have you been treated for an alcohol or drug problem? |

✓ |

.14 (±.45) (0 – 3) |

.67 |

.23 |

−.20 |

.50 |

|

Total SOAPP-R Score |

18.8 (±.11.1) (0 - 69) |

.92 |

.51 |

−.47 |

1.56 |

As Table 2 shows, the entire range of response options (0 to 4) was utilized for all selected items, with the exception of item #8 about having been treated for alcohol or drug abuse, for which the range was 0 to 3. It was important to include items with relatively high mean ratings (i.e., greater than 1) and larger standard deviations (i.e., greater than or equal to 1) to ensure that some of the items would be “sensitive,” that is, endorsed at higher levels, as well as items with a lower means and smaller standard deviation, which reflect “specific” items.

The test-retest intra-class correlations ranged from r = .51 to r = .92 (mean = .69). For the total scale, the test-retest ICC was an excellent .92. Item correlations between the SOAPP-R items and the criterion, the ADBI, ranged from .20 to .41 (mean = .26). Item correlations with the Marlowe-Crowne correlations ranged from −34 to −10 (mean = −.24). Correlation of the total SOAPP-R score with the ADBI was .51 and with the Marlowe-Crowne was −.47. This relatively high level of negative correlation with the Marlowe-Crowne is interesting and highlights the relationship of scores on the SOAPP-R with individuals' willingness to self-disclose. It is of further interest, however, that the SOAPP-R score correlates .51 with the criterion ADBI, while this correlation with the Marlowe-Crowne is only −.23. Thus, the SOAPP-R appears to tell us more about the criterion than merely knowing the Marlowe-Crowne score.

Effect sizes (Cohen's D) were calculated, and all items were found to have a greater than .40 effect size, which suggests moderate to good predictive ability. Table 2 presents the effect sizes obtained for each item, which ranged from .42 to .93 (mean = .58). The total SOAPP-R effect size for all items was 1.56.

Of the original 24-item SOAPP v.1, eight of the items met inclusion criteria and were kept for use in the SOAPP-R (see Table 2: item #3, mood swings; item #6, close friends with alcohol/drug problems; item #7, others suggest you have a drug problem; item #8, attended AA or NA meetings; item #10, treated for alcohol or drug problem; item #12, others expressed concern over use of medication; item #13, felt craving for medication; item #16, legal problems or been arrested). New items that were included reflect content that is not obviously related to prescription opioid misuse such as feeling bored, sensing tension in the house, and having a temper.

Internal consistency of the 24 items included in the SOAPP-R Prediction Score was calculated. Coefficient α (standardized item alpha) for these 24 items was calculated for initial SOAPP-R results (N= 250) and for follow-up retest (N = 49). An α of .88 was achieved for the initial SOAPP-R and .85 was found for the follow-up retest. This suggests reasonably good stability of the scale.

Selection of cutoff scores for the SOAPP-R

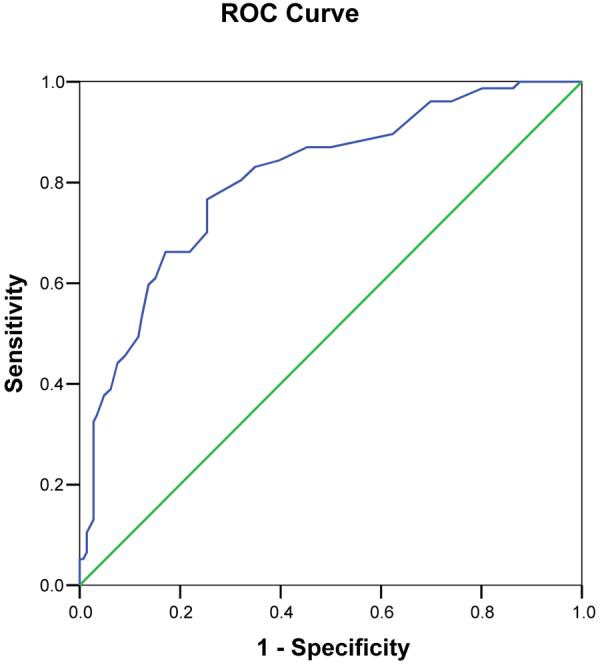

Receiver Operating Characteristics (ROC) curve analyses were conducted for the SOAPP-R Prediction Score from the initial SOAPP-R administration and the Aberrant Drug Behavior Index (positive or negative). Of the 223 patients that were successfully followed, 77 (35%) were identified as positive and 146 (65%) as negative on the Aberrant Drug Behavior Index. The ROC curve is presented in Figure 2. The Area Under the Curve (AUC) was .81 (Standard Error = .031, p < .001). The 95% confidence interval for the AUC was .75 to .87. Table 3 presents the sensitivity and specificity cutoff estimates for the range of the SOAPP-R Prediction Scores gauged against the Aberrant Drug Behavior Index.

Figure 2.

Receiver operating characteristic curve SOAPP-R prediction score sensitivity and specificity estimates gauged against the Aberrant Drug Behavior Index

Note: Diagonal line represents chance prediction.

Table 3.

SOAPP-R prediction score sensitivity and specificity estimates*

| SOAPP Prediction Score positive if greater than or equal to: | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|

| 1.000 | 1.000 | .007 |

| 3.000 | 1.000 | .014 |

| 4.000 | 1.000 | .027 |

| 5.000 | 1.000 | .068 |

| 6.000 | 1.000 | .123 |

| 7.000 | .987 | .137 |

| 8.000 | .987 | .171 |

| 9.000 | .987 | .199 |

| 10.000 | .961 | .260 |

| 11.000 | .961 | .301 |

| 12.000 | .896 | .377 |

| 13.000 | .883 | .438 |

| 14.000 | .870 | .500 |

| 15.000 | .870 | .548 |

| 16.000 | .844 | .603 |

| 17.000 | .831 | .651 |

| 18.000 | .805 | .678 |

| 19.000 | .766 | .747 |

| 20.000 | .701 | .747 |

| 21.000 | .662 | .781 |

| 22.000 | .662 | .829 |

| 23.000 | .610 | .849 |

| 24.000 | .597 | .877 |

| 25.000 | .532 | .884 |

| 26.000 | .494 | .911 |

| 27.000 | .455 | .925 |

| 28.000 | .442 | .938 |

| 29.000 | .390 | .952 |

| 30.000 | .377 | .966 |

| 31.000 | .338 | .973 |

| 32.000 | .325 | . 973 |

| 33.000 | .273 | . 973 |

| 34.000 | .247 | . 973 |

| 35.000 | .221 | . 973 |

| 36.000 | .208 | . 973 |

| 37.000 | .169 | . 973 |

| 38.000 | .156 | . 973 |

| 39.000 | .130 | . 973 |

| 41.000 | .104 | .986 |

| 43.000 | .078 | .986 |

| 44.000 | .065 | .986 |

| 45.000 | .052 | .993 |

| 52.000 | .052 | 1.000 |

| 58.000 | .039 | 1.000 |

| 60.000 | .026 | 1.000 |

| 65.000 | .013 | 1.000 |

| 70.000 | .000 | 1.000 |

Gauged against the drug aberrant behavior index (ADBI)

Note: SOAPP-R Prediction Scores = sum of 24 items rated from 0 to 4, possible range = 0 to 96.

Table 4 presents six values (sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, positive likelihood ratio, and negative likelihood ratio) used to evaluate or determine cutoff scores for three possible SOAPP-R scores. Each value presents a somewhat different picture on the ability of a cutoff score to detect true positives and true negatives, while reducing or minimizing false positives and false negatives. All screening tests produce some false positives and some false negatives, so the decision about which cutoff score to use depends on the provider's judgment about what is best for his or her patients.31 Sensitivity, for instance, is the proportion of patients with the target condition who have a positive test result, while specificity is the proportion of people without the target condition who test negative. The positive predictive value is the proportion of patients with a positive score who have the target condition. It is important to note that, of the values presented, likelihood ratios are least affected by pretest prevalence of the target condition in a particular sample.

Table 4.

Values typically used to evaluate diagnostic tests

| SOAPP Prediction Cutoff Score |

Sensitivity | Specificity | Positive Predictive Value |

Negative Predictive Value |

Positive Likelihood Ratio |

Negative Likelihood Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Score 17 or above | .83 | .65 | .56 | .88 | 2.38 | .26 |

| Score 18 or above | .81 | .68 | .57 | .87 | 3.80 | .29 |

| Score 19 or above | .77 | .75 | .62 | .86 | 3.03 | .31 |

The primary concern regarding use of the SOAPP-R as a screening tool is the chance of missing high-risk patients. This is based on the assumption that it is more problematic to miss a high-risk patient than to misclassify a truly low-risk individual as high-risk. The values presented in Table 4 suggest that the SOAPP-R is satisfactory at identifying those who are at high risk. For example, a score of 18 or higher will identify 80% of those who actually turn out to be at high risk. For this score, the negative predictive value is .87, which means that the vast majority of patients who have a negative SOAPP-R are likely at low-risk. Finally, the positive likelihood ratio suggests that a positive SOAPP-R score (at a cutoff of 18) is 2.5 times as likely to come from someone who is actually at high risk. These data suggest that a cutoff score of 18 or higher may be a reasonably conservative choice for a SOAPP-R cutoff. The sensitivity and specificity value obtained in this study of the SOAPP-R using this cutoff compares well with the values of other medical tests.31

Discussion

The present study reports on an empirically-based, prospective effort to develop and test a revised version of the SOAPP. Similar to the original, SOAPP-R is easily understood by patients, takes little time to administer and score, and taps information believed by experienced professionals to be important for determining which chronic pain patients may have problems with long-term opioid medication. Data collected on a sample of chronic pain patients suggests the SOAPP-R may be a reliable and valid measure of risk potential for aberrant medication-related behavior among persons with chronic pain.

While the SOAPP-R requires additional research, this study suggests that it may be a better alternative than current recommendations (e.g., the CAGE19) that have no empirical base with a chronic pain population. At a minimum, the SOAPP-R can be used to alert the physician to potential risks and avert future problems. Patients' responses to the SOAPP-R questions access information not necessarily obtained during an initial evaluation, especially by a non-specialist. Documentation of these responses might prove helpful in a medical/legal context by providing a basis upon which to decide whether to request more frequent office visits, pill counts, urine toxicology screens, or discontinuation of therapy.

The SOAPP-R has some benefits over the SOAPP v.1. Only 14 of the 24 items in the original SOAPP v.1 were scored, which presented scoring difficulties. The SOAPP-R uses all items, so it is no longer necessary to check which items need to be included in the final score. Items on the SOAPP v.1 were quite transparent (i.e., required patients to endorse behaviors that were more obviously related to substance abuse). Thus, SOAPP v.1 had a very low cut off score, and almost any endorsement of the items could place a patient in the high-risk category. The SOAPP-R, on the other hand, contains more questions that can be endorsed by the respondent without necessarily engendering classification as high-risk. Indeed, out of the 233 patients taking the beta version, only one patient endorsed no items (obtained a score of 0). This suggests that the SOAPP-R may be somewhat less susceptible to overt deception, although a direct test of this hypothesis was not part of the present study.

One might notice that the SOAPP v.1 obtained superior sensitivity (.91 at a cutoff of 7 vs. .81 for the SOAPP-R at a cutoff of 18) and specificity (.69 vs. .68 for the SOAPP-R).6 It is important to remember that, in contrast to the SOAPP v.1, the SOAPP-R was validated against a criterion that included self-report, but also included systematically collected toxicology results and physician report. Those who disclose high risk history or behavior on a screening questionnaire are likely the same individuals who will report problematic behavior in a follow-up interview. This may have inflated estimates of predictive validity for SOAPP v.1. The SOAPP-R was tested against a more stringent criterion, which may account for the decrease in sensitivity and specificity observed.

Like the SOAPP v.1, the SOAPP-R should be used responsibly. The SOAPP-R should be used only with chronic pain patients being considered for long-term opioid therapy. Broad-based administration of the SOAPP-R for all patients with chronic pain would not be appropriate. The SOAPP-R may help the provider determine the level of monitoring appropriate for a particular patient. SOAPP-R scores are based upon the willing and direct responses of patients. While we attempted to create a scale that was not immediately transparent, patients determined to “look good” on the SOAPP-R will not find it difficult to do so. In our initial clinical work with the SOAPP v.1, we found that many patients are truthful in their responses. Yet, it is critical for providers to consider SOAPP-R results in the context of information from other sources, including history and physical examination, the clinical interview, discussions with family members, laboratory findings, and review of medical records.

Selection of a cutoff score for use in any diagnostic test can be a somewhat complicated task. We purposely chose a score that would capture those individuals who may be at risk for substance misuse. All patients prescribed opioids for their pain should read and sign an opioid therapy agreement that outlines the patient's responsibilities and clinic policies.12 Past medical records should be obtained and contact with previous and current providers should be maintained. Patients should be advised of their risk for substance abuse. Patients should also be told that they would be expected to give random urine samples for toxicology screening during clinic visits. Patients should also initially be given medication for limited periods of time (e.g., every 2 weeks). Ideally, family members should be interviewed, and involvement with an addiction medicine specialist and/or mental health professional should be sought if problems arise. Early signs of aberrant behavior and a violation of the opioid agreement could be grounds to taper the medication and refer to a substance abuse program. Those patients with a low score on the SOAPP-R should be least likely to develop a substance abuse disorder. In most such cases, less caution would be warranted about the type of opioid to be prescribed and the frequency of clinic visits. Efficacy of opioid therapy should be re-assessed periodically, and urine toxicology screens and an update of the opioid therapy agreement would be recommended annually for all patients.

The SOAPP-R was devised as a self-report measure to predict future misuse behavior based on past behavior and/or cognition. We have recently developed a questionnaire to be used periodically for those patients who have been taking opioids for an extended period of time, known as the Current Opioid Misuse Measure (COMM).7 The intent of this scale is to document current behavior on a periodic basis in order to continue to justify chronic opioid therapy and to help detect ongoing difficulties. It is our belief that the SOAPP-R and COMM will work in tandem to help identify problems associated with the use of prescription opioids for pain.

It is important to emphasize the limitations of this study. First, this study was conducted in three, anesthesia-based pain centers and included a volunteer sample of patients. Also, not all patients gave a urine sample for a toxicology screening, so there is risk of some selection bias. Continued efforts are needed to validate the SOAPP-R in other settings with all patients prescribed opioids for pain. Usefulness of the present measure in a primary care clinic with patients with shorter duration of pain particularly needs to be determined. Bayes Theorem20 postulates that the predictive value of diagnostic or laboratory tests is not constant but must change with the proportion of patients who actually have the target disorder among those who undergo the diagnostic evaluation. Thus, it is critical that the SOAPP-R not be used as a general screener in a primary care practice. It should be used instead only with chronic pain patients being considered for long-term opioid therapy, regardless of the setting.

A second limitation regards the estimate of test-retest reliability. Patients were not followed for an extended period of time. The results of this study suggest that the SOAPP-R is a reliable measure, but retesting over longer periods of time would be helpful. It is of note that the level of test-retest reliability found in this study compares favorably with that obtained by other well-known measures (cf., SF-3636).

A third limitation reflects use of a self-report screener to predict future behavior. Since it is generally believed that past behavior predicts future behavior,5,26 self-report of past behavior can be clinically useful to identify risk of future aberrant medication-related behavior. Information from background checks on illegal activities or psychiatric history, or records of prescription use obtained by prescription monitoring programs may be very useful, but are difficult and expensive to obtain. Since some patients are not completely honest, the SOAPP-R includes subtle items that are not overtly related to aberrant drug behavior (e.g., feeling bored, impatient, angry) but are empirically related to medication misuse at follow-up. Nonetheless, we acknowledge, like any self-report measure, patients can ‘fake good” on the SOAPP-R.

Finally, the lack of a cross-validation study is a serious limitation of the present work. The cross-validation of the SOAPP-R is currently in progress.

Conclusion

The SOAPP-R provides clinicians with the ability to be more aware of patients who may have greater difficulty modulating their own medical use of opioids and who may require extra monitoring and management. The SOAPP-R will also help clinicians identify which patients are at low risk for addiction or misuse and may require less monitoring. A lack of knowledge and experience with opioids is thought to cause physicians to avoid the use of these medicines despite their proven benefit.16 Use of the SOAPP-R, along with other appropriate patient evaluations, may help providers previously reluctant to use opioids to have greater confidence that certain patients are less likely to misuse these medications and to reconsider a potentially beneficial therapy.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks are extended to MaryJane Cerrone, David Janfaza, Nathaniel Katz, Carla Krichbaum, Edward Michna, Leslie Morey, Sanjeet Narang, Srdjan Nedeljkovic, Bruce Nicholson, Sarah O'Shea, Edgar Ross, Glenn Swimmer, Ajay Wasan, and staff members of Brigham and Women's Hospital, Lehigh Valley Hospital, and PainCare of Northwest Ohio for their participation in this study. This research was supported in part by a grant awarded to the first author (DA015617) from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD and by an unrestricted grant to Inflexxion, Inc. from Endo Pharmaceuticals, Chadds Ford, PA.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Akbik H, Butler SF, Budman SH, Fernandez K, Katz NP, Jamison RN. Validation and clinical application of the Screener and Opioid Assessment for patients with pain (SOAPP) J Pain Sym Manage. 2006;32:287–293. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The American Academy of Pain Medicine, The American Pain Society, and The American Society of Addiction Medicine Definitions related to the use of opioids for the treatment of pain: a consensus document from the American Academy of Pain Medicine, the American Pain Society, and the American Society of Addiction Medicine. Available at http://www.painmed.org/pdf/definition.pdf Accessed August 13, 2007.

- 3.Anastasi A. Psychological testing. fourth edition Macmillian Publishing Co; New York, NY: 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ballantyne JC, Mao J. Opioid therapy for chronic pain. N Eng J Med. 2003;349:1943–1953. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra025411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bentler PM, Speckart G. Attitudes “cause” behaviors: A structural equation analysis. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1981;40:226–238. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Butler SF, Budman SH, Fernandez K, Jamison RN. Validation of a screener and opioid assessment measure for patients with chronic pain. Pain. 2004;112:65–75. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Butler SF, Budman SH, Fernandez KC, Houle B, Benoit CM, Katz N, Jamison RN. Development and validation of the current opioid misuse measure. Pain. 2007;130:144–156. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chabal C, Erjavec MK, Jacobson L, Mariano A, Chaney E. Prescription opiate abuse in chronic pain patients: clinical criteria, incidence, and predictors. Clin J Pain. 1997;13:150–5. doi: 10.1097/00002508-199706000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cleeland CS, Ryan KM. Pain assessment: global use of the Brief Pain Inventory. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1994;23:129–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Compton PJ, Darakjian J, Miotto K. Screening for addiction in patients with chronic pain and “problematic” substance use: evaluation of a pilot assessment tool. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1998;16:355–63. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(98)00110-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fishbain DA, Rosomoff HL, Rosomoff RS. Drug abuse, dependence, and addiction in chronic pain patients. Clin J Pain. 1992;8:77–85. doi: 10.1097/00002508-199206000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fishman SM, Kreis PG. The opioid contract. Clin J Pain. 2002;18:S70–5. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200207001-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jackson D, Usher K, O'Brien L. Fractured families: Parental perspectives of the effects of adolescent drug abuse on family life. Contemp Nurse. 2006;23:321–330. doi: 10.5555/conu.2006.23.2.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jackson KM, Trochim WMK. Concept mapping as an alternative approach for the analysis of open-ended survey responses. Organiz Res Method. 2002;5:307–36. [Google Scholar]

- 15.James LM, Taylor J. Impulsivity and negative emotionality associated with substance use problems and Cluster B personality in college students. Addict Behav. 2007;32:714–727. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jamison RN. Introduction to special edition. Clin J Pain. 2002;18:S1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jamison RN, Kauffman J, Katz NP. Characteristics of methadone maintenance patients with chronic pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000;19:53–62. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(99)00144-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joranson DE, Ryan KM, Gilson AM, Dahl JL. Trends in medical use and abuse of opioid analgesics. JAMA. 2000;283:1710–1714. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.13.1710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mayfield D, McLeod G, Hall P. The CAGE questionnaire: validation of a new alcoholism screening instrument. Am J Psychiatry. 1974;131:1121–3. doi: 10.1176/ajp.131.10.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meehl PE, Rosen A. Antecedent probability and the efficiency of psychometric signs, patterns or cutting scores. Psychol Bull. 1955;52:194–216. doi: 10.1037/h0048070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Michna E, Ross EL, Hynes WL, Nedeljkovic SS, Soumekh S, Janfaza D, Palombi D, Jamison RN. Predicting aberrant drug behavior in patients treated for chronic pain: importance of abuse history. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;28:250–258. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morey LC. Personality assessment screener. Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc.; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morley-Forster PK, Clark AJ, Speechley M, Moulin DEL. Attitudes toward opioid use for chronic pain: a Canadian physician survey. Pain Res Manag. 2003;8(4):189–94. doi: 10.1155/2003/184247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mulvey E. Assessing the evidence of a link between mental illness and violence. Hosp Community Psych. 1994;45:663–668. doi: 10.1176/ps.45.7.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nedeljkovic SS, Wasan A, Jamison RN. Assessment of efficacy of long-tem opioid therapy in pain patients with substance abuse potential. Clin J Pain. 2002;18:S39–51. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200207001-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ouellette JA, Wood W. Habit and intention in everyday life: The multiple processes by which past behavior predicts future behavior. Psychol Bull. 1998;124:54–74. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Portenoy RK, Payne R. Acute and chronic pain. In: Lowinson J, Ruiz P, Millman R, Langrod J, editors. Substance abuse: a comprehensive textbook. Baltimore, MD: 1997. pp. 563–90. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Potter M, Schafer S, Gonzalez-Mendea E, Gjeltema K, Lopez A, Wu J, Pedrin R, Cozen M, Wilson R, Thom D, Croughan-Minihane M. J Fam Pract. 2. Vol. 50. University of California; San Francisco: 2001. Opioids for chronic nonmalignant pain. Attitudes and practices of primary care physicians in the UCSF/Stanford Collaborative Research Network; pp. 145–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramo DE, Anderson KG, Tate SR, Brown SA. Characteristics of relapse to substance use in comorbid adolescents. Addict Behav. 2005;30:1811–1823. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reynolds WM. Development of reliable and valid short forms of the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale. J Clin Psych. 1982;38:119–25. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sackett DL, Haynes RB, Guyatt GH, Tugwell P. Clinical epidemiology: a basic science for clinical medicine. 2nd Ed Little, Brown & Co.; Boston: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Savage SR. Assessment for addiction in pain-treatment settings. Clin J Pain. 2002;18:S28–38. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200207001-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Savage SR, Joranson DE, Covington EC, Schnoll SH, Heit HA, Gilson AM. Definitions related to the medical use of opioids: Evolution towards universal agreement. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003;26:655–667. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(03)00219-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Trochim WMK. An introduction to concept mapping. Eval Prog Planning. 1989;12:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trochim WMK, Cook JA, Setz RJ. Concept mapping to develop a conceptual framework of staff's views of a supported employment program for persons with severe mental illness. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1994;62:766–77. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.4.766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Gandek B. SF-36 health survey: manual and interpretation guide. Quality Metric, Inc.; Lincoln, RI: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wasan AD, Wootton J, Jamison RN. Dealing with difficult patients in your pain practice. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2005;30:184–192. doi: 10.1016/j.rapm.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weaver M, Schnoll S. Abuse liability in opioid therapy for pain treatment in patients with an addiction history. Clin J Pain. 2002;18:S61–69. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200207001-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Webster LR, Dove B. Avoiding Opioid Abuse While Managing Pain: A Guide for Practitioners. Sunrise River Press; North Branch, MN: 2007. [Google Scholar]