Abstract

During the past decades, the traditional state monopoly in urban water management has been debated heavily, resulting in different forms and degrees of private sector involvement across the globe. Since the 1990s, China has also started experiments with new modes of urban water service management and governance in which the private sector is involved. It is premature to conclude whether the various forms of private sector involvement will successfully overcome the major problems (capital shortage, inefficient operation, and service quality) in China’s water sector. But at the same time, private sector involvement in water provisioning and waste water treatments seems to have become mainstream in transitional China.

Keywords: Public-private partnership, Water governance, China

Introduction

In the wake of the United Kingdom’s water privatization in the 1980s, the 1990s witnessed the spreading of privatization and a variety of public-private partnership (PPP) constructions in developing countries, especially following the promotion and push by international development agencies such as the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and others (Nickson 1996, 1998; Kikeri and Kolo 2006). It was believed that private sector participation in the water sector would bring in much needed investment and improve service coverage, quality, and efficiency by replacing conventional public-sector systems suffering from under-investment and inefficiencies due to excessive political interference and rent-seeking behavior by vested state and bureaucratic interests (Hall and others 2005). During the past decades, a wide literature in economics, governance, and public management has provided theoretical and empirical arguments and evidence in favor of further private sector involvement in what used to be public utilities. At the same time, however, debate continues on the different partnership constructions, the division of tasks and responsibilities between public and private sectors, and the social effects coming along with these developments. Topics, such as the relationships between ownership (public or private) and efficiency (Vining and Boardman 1992; Spiller and Savedoff 1997; Birchall 2002; Afonso and others 2005; Anwandter and Jr.Ozuna 2002; Hart 2003), the classification of various public-private constructions and their characteristics (World Bank 2004; Seppälä and others 2001; US National Research Council 2002), the consequences of privatization for governmental regulation (Nickson and Vargas 2002; Pongsiri 2002) and questions of equity and equality are still heavily debated, in particular with respect to the water sector and less so regarding other utilities.

Although private sector participation in the water sector is one of the more controversial topics in public utility management today, this wave also spread to China at the turn of the millennium, where the government started to reform public sectors (water, electricity, roads, etc.) via introducing market functions. The so-called marketization reform expected to address the increase of several water problems (water shortage, insufficient infrastructure, water pollution, etc.) to meet the requirement posed by accelerated urbanization and high economic growth. As a late comer in this field of private sector involvement in the provision of water services, China is able to learn from numerous experiences of other countries, such as the United Kingdom, France, United States, Chile, Philippines, Mexico, Argentina, and Bolivia.

Since the earlier attempts of applying the Build-Operate-Transfer (BOT) approach in the water sector in the 1990s and the full development of marketization reform in public sectors in 2002, China has applied different models of private sector involvement in over 300 water supply and wastewater projects. This marketization reform emphasizes the importance of the market, investment and financial liberalization, deregulation, decentralization, and a reduced role of the state in the water sector (also see Robison and Hewison 2005; Prasad 2006). Tariff reform with full-cost recovery, competitive bidding procedures, changing ownership structures (e.g., public and private, Sino and foreign), and restrictive fiscal policies are part of it.

This article reviews developments in private sector involvement in China’s water management and assesses whether expected results of marketization in the Chinese water sector have been met: raising investment for infrastructure, increasing service coverage and improved efficiency in China’s water supply and wastewater treatment. After interpreting further private sector involvement in China’s urban water management in terms of modernizing water governance, this article provides a country-wide overview of current privatization developments in the Chinese water sector, and subsequently makes an in-depth investigation in three distinct cases with respect to the new roles and functions of the governments and private parties. The final section assesses the current status of privatization programs in China’s water management and its implications of future research on water governance reform.

Private Sector Participation as Part of Modernizing Urban Water Governance

In the debate on private sector participation in environmental governance in general, and urban water governance in particular, we can identify three — sometimes interrelated — discourses.

First, private sector participation goes back to the literature on state failure in the early 1980s. State failure refers to the notion that the nation-state falls short in the provisioning of collective goods, in this case environmental services and quality. Some of the key publications in this regard come from Germany. Martin Jänicke’s (1986) Staatsversagen analyzed the fundamental inability of the nation-state to protect the environment in the 1980s, and called for an innovation or modernization of environmental politics, later to be labeled political modernization (e.g., Tatenhove and others 2000; Mol 2002): a reorientation towards a more preventive, pro-active and flexible strategy using new instruments and closer cooperation with and participation of non-state actors. With a similar analysis of the environmental state’s fundamental inabilities, Joseph Huber (1985) came to slightly different solutions with his strong plea for involving the private sector into environmental services and protection. Finally, around the same time Ulrich Beck (1986) formulated his Risk Society hypothesis and identified subpolitical arrangements (i.e., arrangements for environmental protection and service provision without and beyond the public state) as an alternative for the conventional environmental politics of the nation-state. Inspired by these and several other authors and ideas, from the mid 1980s onward environmental social science scholars started to develop ideas, investigate practices, and formulate theories on governing environmental problems, in which the environmental state was given a less dominant and monopolistic position.

Around the same time (the second half of the 1980s) ideas of further private participation and involvement in the provisioning of environmental services (water, waste, energy, etc.) started to develop, especially in the United States and the United Kingdom. While also here the fundamental idea is involving the private sector in tasks traditionally fulfilled by the public sector, the orientation and literature is slightly different. The majority of the literature comes from the management and organization sciences and the orientation is less focused on state failures and governance, but rather on efficiency, the bringing in of new capital and the introduction of market logics. The dominant form of organizing urban infrastructure (water, energy, waste, transport) by state agencies has been replaced in many places by various PPP constructions, with different reasons put forward to legitimate such new constructions (cf. Linder 1999). At the same time, these partnerships led to considerable debate, most significantly on issues of equity and equality: who is involved in these partnerships, for who are these constructions bringing more effective and efficient services, are local governments able to balance the power of private capital coming in (especially in situations of Transnational Companies (TNCs) in developing countries) (e.g., Oppenheim and MacGregor 2004), and what does private sector involvement mean for affordability of environmental services for the poor?

Thirdly, in the 1990s, following the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (1992, Rio de Janeiro), and even stronger after the Rio+10 conference (2002, Johannesburg), ideas and practices of public private partnerships started to emerge forcefully on the national and global agenda (cf. Mol 2007). In this literature, the emphasis is strongly on transnational partnering of public and private entities, with a strong focus on the role of civil society organizations. The main reason behind the recent attention to private sector participation in environmental protection and service delivery is related to tendencies of globalization and governance complexities. As Davies (2002) correctly summarizes, in this interpretation the notion of partnership has a positive rhetoric referring to inclusiveness, transparency, participation and dialogue, redistribution of power, and equity. And not so much to ideas of efficiencies, capital investment, market logics, and increased service coverage.

In reviewing the arguments and legitimacy of the push for private sector involvement in China’s urban water governance, there is a strong relation to the second discourse on efficiency, capital investments and service coverage, while ideas of state-failure and political modernization incidentally emerge. By the same token, the Chinese discourse on private sector participation in urban water management hardly draws upon ideas of wide cross-sectoral partnerships and the positive logics of transparency, democracy, participation, and dialogue. Discussions on China’s urban water governance reform argue for the advantages of effectiveness and efficiency, and debate the best organizational modes, division of responsibilities, and coordination structures. Potential negative outcomes of private sector participation — so strongly emerging in and dominating western debates — are much less emphasized: loss of decision-making autonomy of states and governments; unequal power relations and information asymmetry in public-private partnerships; problems around equity, access for the poor, participation and democracy in decision-making (e.g., Hancock 1998; Poncelet 2001; Miraftab 2004).

According to the World Bank, China, Chile and Colombia are the only countries that remain active in water privatization after 2001 (Izaguirre and Hunt 2005). How to explain that, while the activities of water sector privatization intend to shrink in an increasing number of countries and international development agencies, such as the World Bank, start to slow down such privatization programs, China is actively promoting private sector involvement in urban water governance?Two interdependent arguments elucidate this. First, China’s urban water management comes from a radically different starting position, where market principles and logics were almost absent. Water management was not just completely publicly organized but also highly inefficient, with large capital shortages, poor coverage, no economic incentives and demand side management, and highly centralized. This is a fundamental, rather than marginal, difference with most of the public utility systems in OECD countries before the privatization discourses and practices of the 1980s and 1990s. Under such Chinese conditions, private sector involvement in water management means more that just handing water business over to for-profit private companies. It most of all means building economic incentives and logics, safeguarding enough financial capital for infrastructure investments, and widening the service area. Second, private sector participation in China’s urban water management is not just a matter of privatization. It is part of a much wider and complex modernization program in urban water governance, involving some of the critical issues that emerged in the privatization debates in OECD countries. The modernization of urban water governance also includes (see OECD 2003, 2004a, 2004b, 2004c, 2005a, 2005b):

water tariff reforms, where costs of drinking water increasingly include full costs (also of wastewater treatment), but come along with safeguards for low income households to continue access to drinking water;

transparency, accountability and control of the government;

public participation in for instance water tariff setting, complaint systems on water pollution and corruption, public supervising committees on utility performance, public and media debates on water governance, disclosure of information to non-governmental actors (cf. Zhong and Mol 2007); and

decentralization of water tasks and responsibilities to the local level.

In exploring the degree, nature, and forms of private sector participation in China’s urban water governance in the following sections; we have to leave these wider — related — developments aside.

Privatization Policy in China’s Water Sector

In China, the term “private sector” has been regarded as politically sensitive since 1949 when China started to establish a socialist regime characterized by the nationalization of ownership. The first breakthrough of the development of “private sector,” which was officially defined as “economic organizations that aim at making profit, in which assets are privately owned and which have eight or more employees” (Provisional Regulations of Private Enterprises in PRC, the State Council, June 25 of 1988), took place mainly in competitive sectors in accordance with the launch of China’s economic reform in the late 1970s. The government remained in control of public sectors such as water services, energy provisioning, waste management, and public transport. In the mid 1990s, Chinese Government attempted to introduce the BOT approach into the field of urban infrastructures (thermal power, hydropower, highway, water supply, etc.) via promulgating the Circular on Attracting Foreign Investment through BOT Approach (No.89 Policy Paper of 1994, the former Ministry of Foreign Trade and Economic Cooperation, January 16 of 1995) and the Circular on Major Issues of Approval Administration of the Franchise Pilot Projects with Foreign Investment (No.208 Policy Paper of Foreign Investment, the former National Development and Planning Commission, the Ministry of Electric Power Industry, and the Ministry of Communications, 1995). These two policy papers formed the first legal ground for private sector involvement and foreign capital investment in Chinese urban infrastructure. Subsequently, the National Development and Reform Commission firstly approved three BOT infrastructure projects in 1996, including Chengdu No.6 Water Supply BOT Plant (B), Guangxi Laibin Power BOT Plant, and Changsha Wangcheng Power BOT Plant (failed).

The earlier experiences of BOT projects brought in needed capital and investment to develop China’s urban water infrastructure. But it illustrated also many problems. The issue of the fixed investment return to investors was one of these problems. After intensifying control over foreign exchanges and loans in the late 1990s, the General Office of the State Council promulgated a specific circular in 2002 to correct foreign investment projects with fixed investment returns, by modifying the relevant contract terms, buying back all shares of foreign investors, transferring foreign investment into foreign loans, or dismantling contracts with often severe losses.

The full-fledged commitment of the Chinese government to private involvement in the water and other utility sectors dates from late 2002. In the December of 2002, the Opinions on Accelerating the Marketization of Public Utilities (No.272 Policy Paper of the MOC, 2002) started the marketization reform of water and other public sectors by opening public utilities to both foreign and domestic investors: multi-financing approaches, concession right and concession management, pricing mechanism, reduction of governmental monopolies and roles ended the traditional policies of public utilities. The subsequent Measures on Public Utilities Concession Management (No.126 Policy Paper of the MOC, 2004; in this policy, “concession management” refers to all forms of private sector participation.) of 2004 specifies the procedure of how to involve the private sectors in public utilities through awarding concession right, but still relies heavily on BOT modes.

These steps proved more than just giving the private sector a permission to enter public utilities. It is a complex process involving among others ownership reforms, redefinition of the role of governments and operators, restructuring the tariff mechanism, reforming governmental regulation, and designing public participation. In the early years of marketization, the emphasis was especially on market opening and financing issues. With Opinions on Strengthening Regulation of Public Utilities (No. 154 Policy Paper, the MOC, 2005) the neglect of governmental regulation and the public good character of water in the previous policy papers was corrected. This policy paper emphasizes that the water sector provide basic public and social goods and that the governmental regulation remains essential (Fu and Zhong 2005). However, there is still a lack of a systematic and comprehensive regulatory framework for the Chinese urban water sectors in practice. The MOC is attempting to introduce and develop a competitive benchmarking system that might be helpful for further regulation, but this is not yet in place. During the authors’ field surveys, the local officials of relevant water authorities are laboring under the lack of effective measurements for regulatory framework, have too much freedom of (non)regulation, and have sometimes an incorrect perception of the government role as a regulator. Fu and colleagues (2006) also refer to the fact that the government has paid some attention to assets regulation while restructuring ownership in the water sector, but neglected regulating water service quality.

Compared to the exponential growth of water projects with significant private sector involvement, the legal basis under privatization developed quite slow and is still underdeveloped in China. Different from some water privatization forerunner countries (e.g., England and Wales, Philippines), which enacted specific laws before entering into privatization, the marketization reform of and private participation in the Chinese water sector is conducted under various governmental policy papers, but without specialized legislation. The current legal codification of public-private partnering in water services is largely a reactive process, where various policy papers address specific problems in the reform process due to the lack of a well-established legal framework. Thus, much room for improvement remains in the current legal basis, for instance on further economic regulation, stronger legislative sanctions, and public participation (cf. Tong 2005; Zhang 2006; Fu and Zhong 2005; Fu and others 2005).

As implementation problems were slowly or not adequately addressed or resolved at the national level, local governments started to issue local policy papers on specific water projects. For instance, the Interim Provision on Administrating Concession Right of Chengdu (No.131 Policy Paper of Chengdu Municipality, 2001) was issued for implementing the BOT project of Chengdu No.6 Water Supply Plant (B), which was the first water BOT pilot project approved by the NDRC. And the Measures on Public Utilities Concession Management of Shenzhen (No.124 Policy Paper of Shenzhen Municipality, 2003) guided the reform of Shenzhen Water Group, the largest water project with private sector involvement in China to date.

The Current Landscape of Private Sector Involvement

In China’s water supply and wastewater services, four major types of private corporations are active (Fu and others 2006): (1) the water transnational corporations (e.g., VEOLIA and SUEZ); (2) Chinese investment developers (e.g., Beijing Capital Group and Tianjin Capital Environmental Protection Co. Ltd.); (3) liberalized water companies (e.g., Shenzhen Water Group and Beijing Sewerage Group); and (iv) environmental engineering corporations (e.g., Beijing Sound Group and Tsinghua Tongfang Water Engineering Corporation). In December of 2004, the Ministry of Construction called provincial-level authorities to summarize marketization of public sectors (e.g., water and wastewater, solid waste, gas, and public transportation). In July of 2005, a follow-up field survey was organized by the MOC, in which the authors have participated. All reported data of this section come from the reports of provincial-level authorities, supplemented by surveys of the Water Policy Research Center of Tsinghua University (in which authors participated).

According to the MOC surveys, various forms of private sector participation can be identified in both water supply and waste water treatment: (1) commercialization of public utilities: it is the transformation of a public agency/utility into an independent corporation; (2) management contract (or namely operations and maintenance contract): it refers to a contractual arrangement in which a private operator manages and maintains the service in a given period but does not have investment obligations; (3) lease contract: it is a short-term contract in which a private operator pays an agreed-upon fee to the government for the right to manage the facility; (4) Greenfield contract (such as BOT, TOT, BOOT, etc.): it means the government commits new investment projects to a private company, within the contract duration, the private operator manages the infrastructure and the government purchases the water by a contracted price (this price isn't necessarily determined by the actual water tariff); (5) concession contract: it is a long-term contract in which a private operator bears responsibilities for operations and maintenance and also assumes investment and service obligations; (6) Joint Venture: it is not a contract but, rather, an arrangement whereby a private company forms a legal entity with the public sector, in which both the private and the public parts share responsibilities and (investment) obligations; and (7) full sale (or full divesture): it is the sale of public assets to the private sector. Table 1 summarizes the various forms of private sector participation and their characteristics. Until July 2005, a total of 152 water supply projects and 200 wastewater treatment projects involved private participation. The total water production capacity of the 152 water supply projects equaled about 17% of national water production capacity of 2004. The treatment capacity of the 200 wastewater projects was over 30 million m3 per day, equaling 67% of the national total wastewater treatment capacity of 2004.

Table 1.

Different forms of private sector participation in China’s water sector

| Form of private sector participation | Asset ownership | Capital investment | Operations & maintenance | Contract period |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commercialization of governmental enterprises/utilities | Public | Public | Public | Indefinite |

| Management contract | Public | Public | Private | 3–5yr |

| Lease contract | Public | Public | Private | 8–15yr |

| Greenfield (BOT-type) | Private/ public | Private | Private | 20–30yr |

| Concession | Public | Private | Private | 25–30yr |

| Joint venture | Shared | Shared | Shared | Indefinite |

| Sale or full divesture | Private | Private | Private | Indefinite |

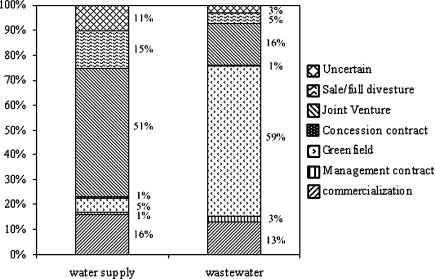

Figure 1 shows the prevalence of different forms of private sector participation in water supply and in wastewater projects. The joint venture approach (including the Sino-foreign joint ventures) has the largest share in the water supply sector with 51% of the 152 privatized projects. The Greenfield modes of private sector participation (including the BOT and TOT contracts) dominated in the wastewater sector, with 59% of the 200 projects. The commercialization of governmental utilities also plays an important role in both water supply (16% of 152 projects) and wastewater (13% of 200 projects). The differences in prevalence of private sector participation forms between water supply and wastewater have a close relation with the level of infrastructure development and with tariff levels. Compared to urban water supply (with service coverage of 88.8%), urban wastewater treatment lags behind, with a service coverage of 45.6% in 2004 (MOC 2005). Direct investment demand for urban wastewater infrastructure (including wastewater treatment, sewers, and sludge treatment) in China is expected to be over 30 billion US dollars between 2006 and 2010, to meet the objective of 60% municipal wastewater to be treated. Accordingly, local governments prefer direct private sector investment in and building of new wastewater infrastructure, resulting in high levels of the Greenfield modalities. In addition, the current low wastewater treatment charges result in a preference for Greenfield modes. In these modes, financing is based on negotiated prices between the government and the private sector and is less dependent to the user fee or charge; drinking water supply costs are much better represented in prices, making joint ventures more likely (Zhong and others 2006).

Fig. 1.

Public sector participation in water: distribution over modalities (2005)

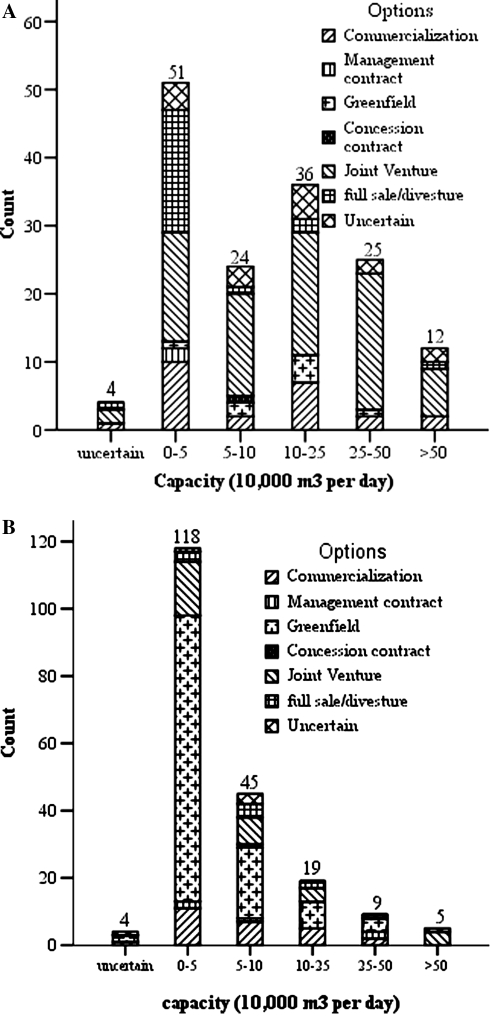

Figure 2 categorizes public sector participation into five groups, according to project capacity. The joint venture approach leads the reform of water supply sector in all size-categories, while the Greenfield approach dominates in wastewater sector, except for projects over 500,000 m3 per day. This might also be related to the different financial risks. Larger projects require much more direct capital investment from the private sector, increasing the financial risk for private investors and moving, then, rather toward joint venture approaches. Furthermore, the full sale/divesture approach occurred more in the field of water sector and mainly in small projects in specific provinces (see Fig. 3). And commercialization is more often found among larger projects. This might be related to not only the larger capital demands of bigger projects, but also huge labor redundancies within such large projects. Existing large water projects are traditionally run by state-owned enterprises with high levels of superfluous workers. For private investors it is often difficult to improve efficiency, because government contracts often do not allow firing existing workers following a commercialization process.

Fig. 2.

Distribution of private sector participation in water projects by capacities

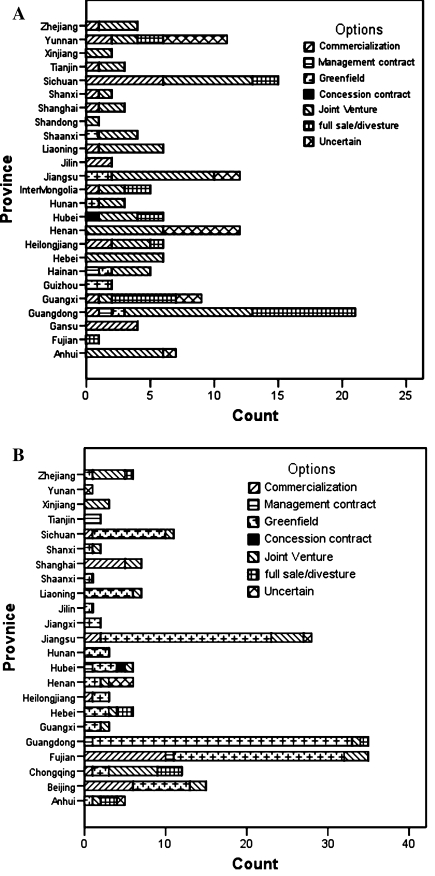

Fig. 3.

Distribution of private sector participation in water projects by provinces

Figure 3 visualizes the provincial distribution of water projects with private sector participation. At least 25 provinces have private sector participation experience in water supply and 23 provinces in wastewater treatment. The form of private sector participation is determined by the level of development of water/wastewater infrastructure, as well as the local economic, social and political conditions. With richer markets, more open economic policies and higher payment capacity of local residents, the southern coastal (e.g., Guangdong and Fujian) and the eastern coastal (e.g., Jiangsu) provinces witnessed high levels of reform in their water sector. Over 60% of foreign private sector investment in water supply projects and about 50% foreign private sector investment in wastewater projects were implemented in these coastal regions, according to the MOC survey. In the meanwhile, the first national BOT pilot project of Chengdu Water Supply (Sichuan Province) has triggered a wave of private sector participation in and around Sichuan Province (including Chongqing and Yunnan). Furthermore, the special environmental protection policies related to “The Three Gorges” dam might have impelled private sector participation in wastewater sector of Sichuan Province and Chongqing.

As shown in Fig. 3, in water supply the joint venture approach dominates in 19 provinces. In the wastewater sector, Greenfield projects (including BOT and TOT) dominate in 12 provinces. The commercialization of traditional state-owned water enterprises was adopted more widely in inland provinces (such as Gansu, Heilongjiang, Jilin, Sichuan, Xinjiang, Yunnan) than in coastal provinces. A joint venture approach for private sector involvement in the wastewater sector was only adopted in provinces with high wastewater treatment charges, such as Beijing, Fujian, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, and Shanghai.

Three Case Studies of Public-Private Partnerships

The reported growing involvement of the private sector has led to radical changes in China’s water management institutions. In this section, we report on fieldwork of three case studies with distinct modes of private sector involvement (a joint venture, a concession, and a Greenfield contract) to analyze in detail the new institutions and relationships between actors in these constructions. During fieldwork in Maanshan and Shanghai, we carried out face-to-face semi-structured interviews with relevant local officials (from the construction authority, price authority, planning and reform authority, state-owned assets administration authority, and environmental protection bureau) and managers of water service providers (water treatment plants/companies, wastewater treatment plants/companies). In the performance assessment project of Macau Water Company Ltd., the managers of relevant departments as well as the representative of Macau Government were interviewed. In total, around 30 interviews were held. While these three cases represent different forms of private sector involvement, they cannot be held representative. All three cases have been assessed positively by the Chinese government and independent researchers (see Fu and others 2006), making them rather best practices than representative cases. But together they illustrate the institutional transformations that come along private sector involvement.

Joint Venture: Maanshan Water Supply

Maanshan City is an industrial, prefecture-level city of 1686 square kilometers, and a population of 1.24 million (2004), of whom 46.8 per cent lives in urban areas. According to the 2004 MOC statistics, 88.7 per cent of the urban population has access to water supply. Water resources are abundant in Maanshan City due to its advantageous location on the south bank of the Yangtze River and abundant annual rainfall (1062–1092 mm). Maanshan Construction Commission (MASCC) is not only the competent authority for water supply and wastewater treatment and as such, plays a leading role in the water sector reform. It is also, as a so-called “Big Construction Commission,” the main governmental agency responsible for urban planning, construction, and management (cf Wu 2003).

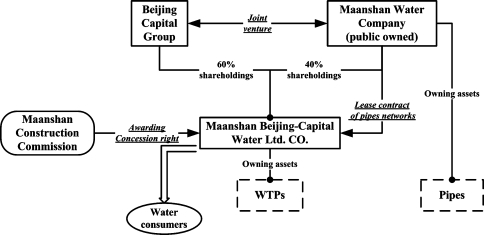

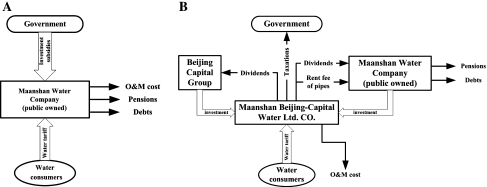

In 2002, following the call of Central Government and Anhui Provincial Government, MASCC embarked upon marketization reform in water and other public utilities (e.g., gas and public transport), widely inviting business actors to become active and invest. The director of MASCC, Mr. Xu, argued that changing the current water institutions and increasing service quality were the most important reasons and objectives for embarking on marketization in the water sector in Maanshan, rather than bringing in nongovernmental capital (personal communication 2004). Marketization was expected to impel and accelerate the reform of converting the old Maanshan Water Supply Company (MASWSC, established in 1958 as state-owned and state-subsidized company with total assets of 4.37 million RMB in 2002, ca. 0.528 million US$ at the exchange rate of 1US$ = 8.277RMB) into a new institutional lay-out. After negotiating with several private companies, MASCC first started — as a kind of trial — a joint venture with Beijing Capital Group (BCG) for one water supply plant (WTP, BCG owning 60% of shares). This joint WTP sold purified water to MASWSC and performed significantly better than other WTPs managed by MASWSC alone. In 2004, MASCC expanded the joint venture cooperation with BCG to all WTPs of Maanshan City, in which BCG obtained a 60% share by bringing in 90 million RMB (ca. 10.875 million US$ at the exchange rate of 1US$ = 8.276RMB). The new joint venture company (MAS-BCWLC) was awarded a 30-year concession right. Both BCG (private sector) and MASWSC (public sector) bear responsibility of investment, operation, and maintenance of the WTPs (excluding the pipe networks) and service obligations (see Fig. 4). With respect to the pipe networks, MAS-BCWLC manages and maintains the existing (pre-2004) network by signing a lease contract with MASWSC, which remained owner of the assets and bears the financial obligations (debts). In the meanwhile, MAS-BCWLC is requested to invest in new pipe infrastructure in new development areas and in nonpiped neighborhoods.

Fig. 4.

Organizational structure of Maanshan water supply system

Within the new joint venture structure, the board of MAS-BCWLC (4 members from BCG and 3 from WASWSC) is the current decision-maker regarding planning (within the objectives set by the municipal master planning), investment and financing, partly replacing the tradition of government decision structures. According to the contract, the general manager of the joint venture company comes alternately from MASWSC and BCG. Taking into account the social dimensions of water provisioning, the government claimed three key conditions in the agreement with the concessionaire: first, the concessionaire (MAS-BCWLC) must ensure sufficient and safe water provision and the government can take over all facilities without any indemnity if the concessionaire fails; second, the concessionaire cannot change the public and social nature of water and should include relevant social responsibilities as governmental requirements (e.g., employing all personnel from the old water company, providing free water for firefighting, reducing/subsidizing water bills of the poor); third, the government controls the water price.

In order to ensure high-quality water and service, MASCC regulates the performance of MAS-BCWLC via assessing annually the specified objectives approved by both the MAS-BCWLC board and MASCC. For instance, MAS-BCWLC was requested to achieve 12 key objectives in 2004: (1) investment of 18 million RMB (ca. 2.175 million US$ at the exchange rate of 1US$ = 8.276RMB); (2) selling 48 million cubic meter water or more and reclaiming >90% of water bills; (3) fulfilling indicators of water service quality (for instance, >99% of the control points should reach the required water quality standards; >98% control points should reach standards for water pressure; a maximum of 30% water loss; burst pipes repairs within maximum time limits); (4) fulfilling all MASCC indicators for safe work; (5) construction of the main body of the No.4 WTP and 25 kilometer new pipes; (6) fulfilling client service indicators (for instance, 100% good client service; >90% public satisfaction); (7) fulfilling the reconstruction of Xiangshan Town water supply system; (8) elaboration and submitting a water supply plan; (9) achieving the relevant objectives of National Civilized City Assessment System (which was proposed by Central Cultural and Ideological Building Commission in 2004; it includes 119 indicators); (10) submitting water supply plans to Municipal People’s Congress and Municipal People’s Political Consultative Conference; (11) responding adequately to complaints and reporting this information to the government; and (12) take anti-corruption measures.

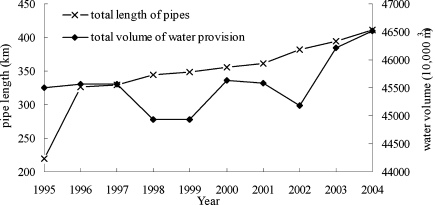

After establishing the joint venture in 2002, the total length of pipes and the volume of water provision have increased (see Fig. 5) and MAS-BCWLC has been in compliance with all requirements of the government, according to interviews with local officials. From 2004 to 2005, MAS-BCWLC has invested about 90 million RMB (ca. 10.875 million US$ at the exchange rate of 1US$ = 8.276RMB) for building new infrastructure, updating old facilities and aged pipes, and establishing a customer service system. In the meanwhile, the government has stopped subsidizing WTPs after the involvement of BCG and the joint venture even turned over about 18.7 million RMB (ca. 2.260 million US$ at the exchange rate of 1US$ = 8.276RMB; including 2 million RMB of the rent fee for pipe networks, 4.7 million RMB of dividends, 7.7 million RMB of corporate income tax, 3 million RMB of value added tax, and 1.3 million RMB of the expense of other taxation; the total taxation of 12 million RMB is about 25% of the total turnover of MAS-BCWLC in 2004) to the local government in 2004. The improved service quality of water provision not only satisfied the consumers, but also resulted in government (and the price public hearing; cf. Zhong and Mol 2007) support for the first tariff reform after private sector involvement in 2004. Maanshan Government increased the water tariff from 0.83 to 1.08 RMB/m3 (ca. 0.10 to 0.13 US$/m3 at the exchange rate of 1US$ = 8.276RMB; rate for household consumers) and indirectly subsidized MAS-BCWLC by moving the additional tax of water provision (e.g., 0.05 RMB/m3 for household consumers) to the income of the joint venture water company. In 2004, the per capita annual income of urban households of Maanshan was 10,189 RMB (ca. 1231.15 US$ at the exchange rate of 1US$ = 8.276RMB), of which around 1.16% was spent on water services (calculated based on daily household water use of 300 liters per capita).

Fig. 5.

Total length of pipes and annual water provision in Maanshan (1995–2004)

Obviously, the involvement of BCG has brought in additional capital to develop Maanshan’s water supply sector. But more importantly it has changed the institutional structure, improved the water service quality and quantity, as well as reduced the governmental input in this field (see Fig. 6). In this structure, the government benefits both from the taxations and dividends of the joint venture company, while transferring part of the financial, building, and operational risks to the private sector. Following this model of Maanshan City, BCG has successfully expanded its activities to other cities, such as Huainan (Anhui Province), Baoji (Shanxi Province), and Yuyao (Zhejiang Province).

Fig. 6.

Monetary flow within Maanshan water supply

However, this private sector involvement practice of Maanshan is argued to have a (potential) political risk due to the lack of a sound legal basis. In transitional China, in particular, policies are perceived to be instable and insufficiently law-based. Until now, details on measures and rules to regulate private utility companies are still missing in current national and Anhui provincial policy papers (Maanshan has no legislation right). This is a common problem in Chinese marketization practices in the water sector, as argued by many lawyers and academics. For instance, Shenyang water supply has experienced several failed marketization practices due to the constantly changing policies and decisions of the local government during 1995–2000 (field survey 2004).

Concession Contract: Macau Water Supply

Macau is one of the two Special Administrative Regions of China, together with Hong Kong. Administrated by Portugal until 1999, it was the oldest European colony in China, dating back to the 16th century. As a small territory of 28 km2 on the southern coast of China, consisting of a peninsula and the islands of Taipa and Coloane, it has a population of 508,000 (2006).

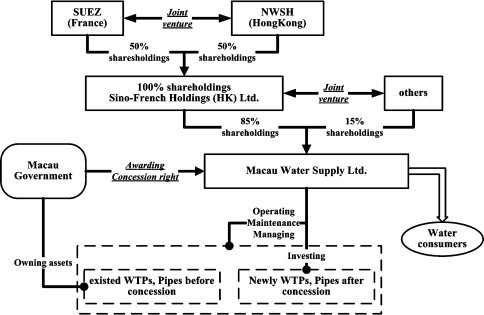

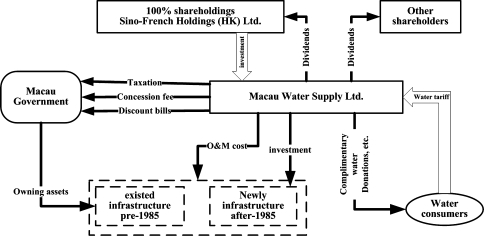

Macau has a long history in the private provision of drinking water, since the earliest Macau Water Company Ltd. (MWC) was founded in 1932 as a full private capital company invested by individuals. Three years later, MWC was taken over by a British Electricity Lighting Company for 10 years and since 1946 by the president of the Macau Economic Department and other individual shareholders. Due to lack of capital and advanced technologies, Macau had an inadequate water supply service with poor water quality and discontinuous water provision during the 1970s. In 1985, Macau Government, learning from the concession management practices in the French water sector, awarded a consortium of two private companies, NWS Holding Limits (Hong Kong) and SUEZ Environment (France), a 25-year concession contract. Macau Government remained owner of the existing, pre-1985, assets (plants and pipe networks), while the private Macau Water Supply Ltd. (MWSL, the former MWC) bears responsibilities for operations and maintenance of these assets, as well as for new investments and service obligations (see Fig. 7). This concession contract is not only the first private sector participation construction in Chinese water sector, but also the first contract that seems to end with a positive result.

Fig. 7.

Organizational structure in Macau water supply

Distinct from the previous private owners, who had little experience in the field of water provision, SUEZ (France) brought in advanced water knowledge and technology. According to the concession contract, MWSL must provide high-quality water supply service, as well as bear several obligations, such as planning, investment, construction, operation, and maintenance of the infrastructure under the supervision of Macao Government. In practice, Macau Government has delegated tasks, responsibilities and obligations to a very large degree to MWSL.

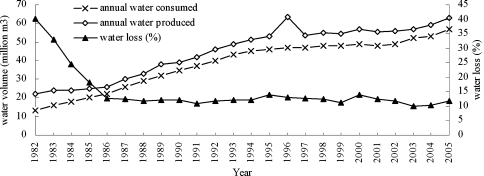

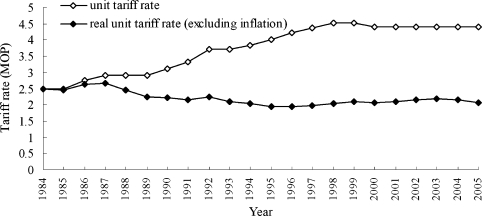

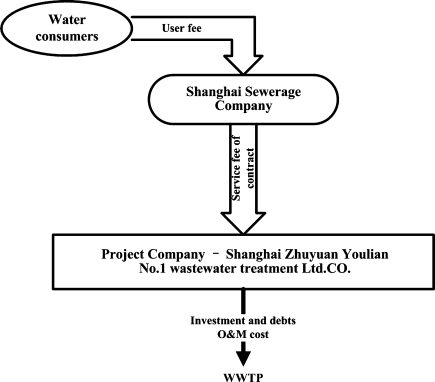

Coming to the end of the 25-year concession contract, MWSL has fulfilled almost all terms of the initial contract. It has, among others, considerably improved water service quality by increasing service access and provision, decreased the loss of water leakage (see Fig. 8), and kept water tariff (corrected for inflation) at a stable level (see Fig. 9).

Fig. 8.

Annual water demand-provision and water loss in Macau (1982–2005)

Fig. 9.

Water tariff rates of Macau (1982–2005)

In the concession contract, the government did not specify conditions and safeguards for the poor. But in practice, MWSL not only reduced the water bill for low-income, disabled and other vulnerable groups. For instance, MWSL has launched the “Elderly-In-Needs” water subsidy program in 2001, which offers those aged over 55 free water consumption of 5 m3 per month. Since May 2005 the “Water for All” program offers free water consumption to other categories of people in needs, such as single-parent families and disabled. But also in addition, it built two potable “Wallace fountains” (a special public fountain with potable water) in Macau, providing free potable water to tourists and citizens. MWSL has also been active in various social welfare and charity activities, providing total donations of 2.08 million MOP (1MOP = 0.965RMB, 2007; ca. 0.26 million US$ at the exchange rate of 1US$ = 8.276RMB) during 2002–2005. During 1985–2005, MSWL also charged discounted water tariffs for governmental agencies, and handed in over 260 million MOP (1MOP = 0.965RMB, 2007; ca. 32.56 million US$ at the exchange rate of 1US$ = 8.276RMB) of taxes and about 56 million MOP (1MOP = 0.965RMB, 2007; ca. 7.012 million US$ at the exchange rate of 1US$ = 8.276RMB) of concession fees to the government.

In both Maanshan and Macau, the water tariff is the main financial source for water companies, while governmental subsidies have been abandoned. Accordingly, whether the water tariff can cover the costs is significant. In the case of Macau, the Macau Government owns the pre-concession infrastructure assets, which demands a smaller first investment from the Consortium. The water tariff could easily cover the cost of operation and maintenance (and not the huge capital costs of existing assets). Unlike the joint venture construction in the Maanshan case, Macau Government leaves all financial responsibilities to the private sector after the concession, and benefits from taxes, concession fees and discounts on government water bills (see Fig. 10). Due to the limited initial investments of the private consortium, sharp water tariff increases were avoided after privatization (often one of the major reasons for public resistance and failed private sector participation in other countries). The local government still owns part of the infrastructure assets, in particular the pipes system, with huge sunk-costs.

Fig. 10.

Monetary flow within Macau water supply

Macau is also an interesting case because of the unique regulatory system, which includes the water quality regulator (IACM), and a unique Government Delegate. IACM is in charge of the water quality regulation, and monitors and controls drinking water quality by random sampling and analysis of over 70 water samples around Macau everyday. The Government Delegate is not a government official, but an individual working in another public utility company and appointed by the government. Following Macau laws, Mr. Lin Runzhong, the Government Delegate for water supply, was appointed for a period of five years by the Macau Government, and is not only the regulator of MWSL, but also an important linkage between MWSL and the government. He participates at all MWSL board meetings and reports relevant information and documents to the government. The Government Delegate decides which information is considered relevant. He is also in charge of assessing the performance of MWSL, and comments on the five-year plans and tariff plans before MWSL sends these to the government for approval. The Macau government generally follows the comments and assessments of the Government Delegate. In this sense, the nongovernmental Government Delegate is defined a specified role and powerful position in governing the water sector. This institutional arrangement relates to the small size of Macau Government, where only a limited state capacity (in quantitative and qualitative terms) is available for numerous public tasks. In conclusion, it can be argued that after 1985 the Macau government has played a meager role in the drinking water management.

Greenfield Contract: Shanghai Wastewater

The Greenfield contract (e.g., BOT, TOT) is the dominant form of private sector participation in wastewater sector reform throughout the country. Shanghai Zhuyuan No.1 WWTP project is one of the most famous Greenfield projects in China. It is presently one of the largest WWTP in China, with a treatment capacity of 1.7 million m3 per day and an advanced primary treatment, serving an area of 107 km2 and about 23.5 million inhabitants. But it also has become famous for the lowest service price: 0.22 RMB (ca. 0.0266US$ at the exchange rate of 1US$ = 8.276RMB) per cubic meter treated wastewater.

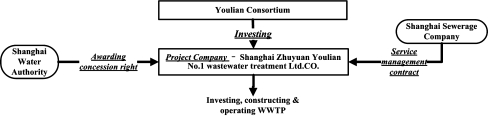

In 2002, the Youlian Consortium (consisting of Youlian Development Company with 45% shares, Huajin Information Investment Ltd. Company with 40% shares, and Shanghai Urban Construction Group with 15% shares) won the open tender for Zhuyuan No.1 WWTP project by bidding the lowest treatment costs. A Project Company (Shanghai Zhuyuan Youlian No.1 Wastewater Treatment Ltd. CO.) was established and awarded a 20-year concession agreement by Shanghai Water Authority. A service management contract was signed with Shanghai Sewerage Company (a fully state-owned company administrated by the government) including details of rights and obligations. Two years later, Youlian Development Company withdrew from this project by transferring the shares and obligations to InterChina Holdings Group (see Fig. 11).

Fig. 11.

Private sector involvement in Shanghai wastewater treatment

According to the agreement between Shanghai Water Authority and the private company, Shanghai Water Authority should minimize its interventions in the construction, operation, and maintenance of WWTP and limit them to safeguarding public health and safety. All conditions and objectives with regard to water service quality are defined in the service contract between Shanghai Sewerage Company and the private company. Among others, the private company has to install an on-line monitoring system and is requested to invite an authorized third party for regular monitoring (on indicators such as BOD5, CODcr, SS, NH4-N, and phosphate). This should be paid by the private company, while reporting to the Shanghai Sewerage Company and should take place within five days. Shanghai Sewerage Company may conduct random water examination at any time. According to the local officials, Shanghai Zhuyuan WWTP has fulfilled all responsibilities and obligations required by the contract up till now, including meeting the water quality standards.

In the case of Shanghai Zhuyuan Greenfield project, the government has transferred its traditional responsibilities of investment, construction, operation, and maintenance (for the contract period) to the private Project Company, accompanied by paying a service fee (see Fig. 12). Different from the joint venture construction in Maanshan and the concession construction in Macau, in which corporate profits directly depend on the water tariff, the private operator within a Greenfield contract is paid a service price negotiated between the government and the private sector. This service price depends on the investments and agreed performance levels, rather than on the user fee level, and which provides the private sector with the financial risks. Accordingly, the low service price of Zhuyuan No.1 WWTP (which was 42% less than the projected costs by government) presented in the public bidding, was argued to have a close relation to earlier governmental input in this project. Shanghai Water Assets Management Development CO. Ltd., a fully public-owned company, was in charge of the pre-phase design and invested about 30 million US dollars in the fixed infrastructure of this project, while the government provided the land free of charge to the operator. Strictly speaking, Shanghai Zhuyuan No.1 WWTP Greenfield project is a quasi-BOT project, due to the fact that part of the investment comes from the government.

Fig. 12.

Monetary flow within Zhuyuan Greenfield project

The experience of Shanghai is an example of full governmental delegation of the daily management of WWTP to the private sector, while financial support via subsidies and preferential policies (e.g., land use) facilitate privatization with low service prices. It is, however, too early to fully assess the success of this project. Some BOT WWTP projects in other cities have met problems following gaps in the current national policy documents. For instance, projects in Foshan (Guangdong Province) could not run properly due to conflicts over current land use right. And projects in Beijing were delayed during the financing process because the domestic private actors met difficulties in obtaining loans from domestic banks due to the lack of a sound loan policy. The commercial banks couldn’t provide long-term loans as required for BOT-types projects as their credit policies are restricted for the private sector (Zhong and Fu 2005), while the China Development Bank can provide long-term loans for BOT-types projects only for a limited number of clients (Chang and others 2006).

Conclusions

With the emergence and blossoming of various forms of private sector involvement in the Chinese water sector, the traditional structure of full governmental provision of water supply and wastewater treatment has changed dramatically. The analysis in this article has provided evidence of the contribution of these new modes to increased capital investment, and especially of more efficient operations and improved service provision. In that sense, the original goals of the Chinese government to embark upon private sector involvement in water provisioning and treatment have been met. However, the early stage that most contracts are in, and the not yet crystallized forms and modes of privatization, prevents us from drawing any final conclusions on the impact of private sector involvement in the Chinese water sector.

From the three casestudy projects with private sector participation, we can draw some lessons for how to successfully involve the private sector into the provision of water services. Firstly, a balance between the water tariff level, profits of investor and governmental subsidies is required. As Hall and Lobina (2005) state, most practices of water privatization fail due to public resistance following sharp price increases and job losses. In China, this has not (yet) been the case, due to large increases in efficiencies and governmental support to fixed infrastructure assets, reducing financial risk of the private sector and limiting the need for large water tariff increases. At the same time, the significant economic growth levels enables local residents to cope with some tariff increases, the poor and disadvantaged have been subsidized by the government, job losses have been minimized following social policies, and public hearings have contributed to higher levels of legitimacy. This all contributed strongly to a relatively smooth transformation of China’s water sector.

Secondly, the selection of the PPP form has a close relation with the level of local water tariff. As illustrated by this article, Greenfield projects appear to be applied when tariffs are not sufficient, especially in the wastewater sector (see also Zhong and others 2006), while Joint Venture approaches are often used in cities with sufficiently high water tariff, in particularly in the water supply sector.

Thirdly, it is crucial to accelerate the establishment of systematic and comprehensive governmental regulatory framework, as the current ad hoc, fragmented and diverse regulatory system endangers efficiency in water service development and certainty and stability for foreign investors. Experiences in many countries have proven that regulation is a key aspect in successful privatization in the water sector and a competitive benchmarking system is regarded as useful in an effective regulatory approach. In late 2006, the MOC attempted to develop a Chinese water supply benchmarking system, which is still ongoing. However, the current private sector involvements in the Chinese water sector still face many legal and regulatory uncertainties. Too often local authorities experiment with systems of governmental regulation and control, or — as in Macau — seem to become marginalized. According to interviews with local officials during our fieldwork, the importance of establishing a workable regulatory and legal system is essential. Guaranteeing sufficient and safe water service to the public is jeopardized by the fact that governments can no longer fully control the planning, operation, and management of water services as before private sector participation. This might only be signs of uneasiness with the new water institutions and division of tasks and responsibilities, but can also be the heralds of an emerging debate on privatization in the Chinese water sector.

Finally, but not least, it is important to identify the differences in risk allocations in the water (service) market between the public and private sectors within different modes of PPP. As Table 1 and the three case-study projects illuminate, with the various forms of privatization, the government often transfers (smaller or larger parts of) financial risks, building risks, and operation and maintenance risks to the private sector. Meanwhile, in the end the government can always take over all facilities without paying an indemnity to the private sector if a concessionaire fails in obtaining the goals as formulated by governmental authorities, or some conflicts emerge in the further policies (e.g., the terminated contracts that are regarded as providing the private sector a fixed investment return). In that sense, the still unstable legal base in transitional China provides a major political and transfer risk for private investors.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support from the Ministry of Construction, the World Bank, and numerous local officials and water companies interviewed during field work, 2004–2005.

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- Afonso A, Schuknecht L, Tanzi V (2005) Public sector efficiency: An international comparison. Public Choice 123:321–347

- Anwandter L, Ozuna T Jr (2002) Can public sector reforms improve the efficiency of public water utilities? Environment and Development Economics 7:687–700

- Beck U (1986) Risikogesellschaft. Auf dem Weg in eine andere Moderne, Frankfurt: Suhrkamp

- Birchall J (2002) Mutual, non-profit or public interest company? An evaluation of options for the ownership and control of water utilities. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics 73(2):181–213 [DOI]

- Chang M, FU T, Zhong L (2006) Policy-based finance and urban water sector reform (in Chinese). China Water& Wastewater 22(10):77–80

- Davies AR (2002) Power, politics and networks: shaping partnerships for sustainable communities. Area 34(2):190–203 [DOI]

- Fu T, Zhong L (2005) Commentary: the MOC. Opinions on Strengthening Regulation of Public Utilities (in Chinese), at: http://www.h2o-china.com

- Fu T, Zhong L, Chang M (2005) Case studies and recommendation of concession management in water sector. In: Fu T, Chen J, Zhong L et al Twelve Key Issues of Urban Water Sector Reform (in Chinese). China Architecture & Building Press, Beijing

- Fu T, Chang M, Zhong L (2006) Chinese Urban Water Sector Reform: Empirical Experiences and Case Studies (in Chinese). China Architecture & Building Press, Beijing

- Hall D, Lobina E (2005) The relative efficiency of public and private sector water, Report commissioned by Public Services International (PSI), at: http://www.world-psi.org

- Hall D, Lobina E, de la Motte R (2005) Public resistance to privatization in water and energy. Development in Practice 15:3–4

- Hancock T (1998) Caveat partner: reflections on partnership with the private sector. Health Promotion International 13(3):193–195 [DOI]

- Hart O (2003) Incomplete contracts and public ownership: Remarks, and an application to public-private partnerships. The Economic Journal 113:C69–C76 [DOI]

- Izaguine AK, Hunt C (2005) “Private Water Projects”, in Note of Public Policy for the Private Sector by the World Bank Group 297

- Huber J (1985) nbogengesellschaft: Ökologie und Sozialpolitik. Fisher Verlag, Frankfurt

- Jänicke M (1986) Staatsversagen. Die Ohnmacht der Politik in die Industriegesellshaft, München: Piper

- Kikeri S, Kolo A (2006) “Privatization Trends” in Note of Public Policy for the Private Sector by the World Bank Group 303

- Linder SH (1999) Coming to Terms With the Public-Private Partnership. A Grammar of Multiple Meanings The American Behavioural Scientist 43(1):35–51 [DOI]

- Miraftab F (2004) Public-Private Partnerships. The Trojan Horse of Neoliberal Development? Journal of Planning Education and Research 24:89–101 [DOI]

- Mol APJ (2007). Bringing the environmental state back in: partnerships in perspective, In: Gasbergen P, Biermann F, Mol APJ (Eds), Partnerships, governance and sustainable development, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar

- Mol APJ (2002) Political Modernisation and Environmental Governance: between Delinking and Linking. Europæa. Journal of the Europeanists 8(1–2):169–186

- Nickson A (1996) Urban Water Supply: Sector Review. University of Birmingham: School of Public Policy, Paper in the role of Government in Adjusting Economies7

- Nickson A (1998) Organizational structure and performance in urban water supply: the cae of the SAGUAPAC cooperative in Santa Cruz, Bolivia Paper presented at 3rd CLAD Inter-American Conference, Madrid

- Nickson A, Vargas C (2002) The limitations of water regulation: The failure of the Cochabamba Concession in Bolivia Bulletin of Latin American Research 21(1):99–120 [DOI]

- OECD (2003) Public sector modernization. Policy Brief

- OECD (2004a) Public sector modernization: Modernizing pubic employment. Policy Brief

- OECD (2004b) Public sector modernization: Changing organizational structures. Policy Brief

- OECD (2004c) Public sector modernization: Governing for performance. Policy Brief

- OECD (2005a) Public sector modernization: Open government. Policy Brief

- OECD (2005b) Public sector modernization: Modernizing accountability and control. Policy Brief

- Oppenheim J, MacGregor T (2004) Democracy and public-private partnerships. International Labour Office

- Poncelet EC (2001) A Kiss here and A kiss There: Conflict and Collaboration in Environmental Partnership Environmental Management 27(1):13–25 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ponsiri N (2002) Regulation and public-private partnership. The International Journal of Public Sector Management 15(6):487–495 [DOI]

- Prasad N (2006) Privatization results: Private sector participation in water services after 15 years. Development Policy Review 24(6):669–692 [DOI]

- Robison R, Hewison K (2005) Introduction: East Asia and the Trials of Neo-Liberalism. Journal of Development Studies 41(2):183–96 [DOI]

- Seppälä O, Hukka J Katko TS (2001) Public-private partnerships in water and sewerage services – Privatization for profit or improvement of service and performance? Public Works Management & Policy 6(1):42–58 [DOI]

- Spiller PT, Savedoff W (1997) Commitment and governance in infrastructure sectors, In: Willig, Uribe, Basaňes (eds) Can Privatization Deliver Infrastructure for Latin America? Balitmore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press

- Tatenhove, van J, Arts B, Leroy P (Eds) (2000) Political Modernisation and the Environment. The Renewal of Policy Arrangements. Dordrecht: Kluwer

- Tong X (2005) Problems of local legislation for concession management (in Chinese) at: http://www.h2o-china.com

- US National Research Council. (2002) Privatization of Water Services in the United States, National Academy Press: Washington DC

- Vining A, Boardman A (1992) Ownership vs. Competition: Efficiency in public enterprise, Public Choice 123:205–239 [DOI]

- World Bank (2004) Public and Private Sector Roles in Water Supply and Sanitation Services, the World Bank: Washington DC

- Wu X (2002) Models of urban management institutions and the development trends (in Chinese). Urban Management 6

- Zhang L (2006) Water regulation needed to improve (in Chinese). November 17 of 2006 at: http://www.h2o-china.com

- Zhong L, Fu T (2005) BOT applied in Chinese wastewater sector, paper presented on ADB workshop on Sanitation and Wastewater Management: The Way Forward, Malina pp. 19–20

- Zhong L, Wang X, Chen J (2006) Private participation in China’s wastewater service under the constraint of charge rate reform, Water Science and Technology: Water Supply 6(5):77–83 [DOI]

- Zhong L, Mol APJ (2007) Emerging environmental democracy in China: Public hearings on water tariff setting. Journal of Environmental Management (forthcoming) doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2007.04.018 [DOI] [PubMed]