Abstract

Aim

To compare body image and weight control behavior among adolescents in Lithuania, Croatia, and the United States (US), the countries with striking contrasts in the prevalence of overweight among adolescents.

Method

The study was carried out according to the methodology of the Health Behavior in School-aged Children collaborative survey. Nationally-representative samples of students, aged 13 and 15, were surveyed in Lithuania (3778 respondents), Croatia (2946 respondents), and the US (3546 respondents) in the 2001/2002 school year.

Results

In all three countries, girls perceived themselves as being “too fat” more frequently than boys (37.0% vs 19.7%, P<0.001, z test). The prevalence of this perception increased with age among girls (32.7% vs 41.1%, P<0.001, z test) and decreased among boys (21.4% vs 17.9%, P = 0.005, z test). Lithuanian adolescents were least likely to perceive themselves as “too fat;” this perception was significantly more frequent in Croatia and the US (24.2%, 27.5%, and 34.3%, respectively; P<0.001, χ2 test). With the exception of 15-year-old Lithuanian boys, in all respondents the proportion of adolescents with body mass index (BMI) ≥85th percentile who perceived themselves as “too fat” was significantly higher (up to 3.13 times among 15-year-old US girls) than the proportion of adolescents with BMI ≤15th percentile who perceived themselves as “too thin.” The highest proportion of overweight boys and girls on a diet or doing something else to lose weight was found in the US. Boys in Lithuania were most likely to be satisfied with their weight regardless of their weight status.

Conclusion

Perceived body image and weight control behavior differ among adolescents in Lithuania, Croatia, and the US. Cross-cultural, age, and sex influences moderate body image and weight control behavior in underweight and overweight adolescents.

The prevalence of overweight and obesity among adolescents is rising rapidly in many countries around the world, including Europe (1). Parallel to the rise in obesity, there is an increase in body dissatisfaction among adolescents (2,3). Previous studies have found that body dissatisfaction is a strong predictor of unhealthy weight control practices (4,5), and restrictive dieting and unhealthy or extreme weight control methods are frequently used by adolescents attempting to achieve an internalized image of ideal body (6). Longitudinal studies have indicated that dieting also predicts weight gain and obesity (7,8). Furthermore, weight control behavior is associated with a wide range of health risk behaviors and psychological problems (9). Thus, frequent weight control associated with poor body image can lead to significant health risks or has potentially serious medical and social consequences.

Psychologists define adolescence as a critical period with respect to psychological development of self-image. The association between self-image and mental health is particularly important, since during this period these newly developed cognitive abilities facilitate self-reflection (10,11). Sociocultural theories of body image and empirical research pertinent to them suggest that unrealistic cultural standards of beauty contribute to adolescents’ body dissatisfaction (12). Body dissatisfaction has serious physical and psychological consequences, so further study is needed on cultural and sex differences in these attitudes.

Body dissatisfaction problems, which are prevalent in adolescents worldwide, can be incorporated into discussions on perceptions of physical appearance and suggest new hypotheses. Recent international data suggest that of the 34 countries, which conducted the Health Behavior in School-age Children (HBSC) study in 2001/2002, the US had the highest and Lithuania had the lowest prevalence of overweight and obesity in adolescents (13,14).

The aim of this article is to compare body image and weight control behavior among adolescents of Lithuania, Croatia, and the US, selected as the countries with different cultural context and a striking contrast in the prevalence of overweight among adolescents. We hypothesize that body weight perceptions among adolescents and weight control behavior pertinent to them differ across countries. Moreover, cross-cultural comparisons may indicate whether the influence of being underweight or overweight on body image and dieting is a universal characteristic of adolescence or if there are cultural, age, or sex influences that moderate this relationship (9).

Methods

Samples and survey procedures

Our analysis was based on the data from the HBSC survey in 2001/2002, a cross-national study supported by the World Health Organization Office for Europe. HBSC project has been described in detail elsewhere (15). Data from three participating countries were selected from the verified international data file (16). The US was selected because it had the highest, Lithuania because it had the lowest, and Croatia because it had medium prevalence of overweight among adolescents (13,14).

Each country received an approval to conduct the survey from an ethics review committee or an equivalent regulatory body. A cluster sample design was used in each country, sampling school classrooms to obtain recommended self-weighting samples and to meet the required precision for the country representative estimates. The data were collected in classrooms by self-completed questionnaires. For all participating countries, response rates were over 90%. The national data files were prepared and presented to the International HBSC Data Bank at the University of Bergen in Norway where the data were checked and processed prior to statistical analyses.

The current analyses included 3778, 2946, and 3546 respondents, 13 and 15 years old, from Lithuania, Croatia, and the US, respectively. We restricted our analyses to these age groups because they provide better reliability in self-reported weight, height, and self-image and report a diversity of weight control behaviors.

Questionnaire and variables

The standard anonymous HBSC study questionnaire, which was developed by the international network of researchers, was used as the survey instrument (16). The following two questions were used for calculation of Body Mass Index (BMI): “How tall are you without shoes?” and “How much do you weight without clothes?” BMI was calculated using the standard metric formula (weight/height [kg/m2]) and categorized into percentiles within sex and age groups in each country sample separately. Respondents were classified as underweight (≤15th percentile), normal weight (>15th percentile and <85th percentile), and overweight (≥85th percentile).

For the evaluation of body image perception, a third question was asked: “Do you think your body is?” Possible responses were the following: “much too thin,” “a bit too thin,” “about the right size,” “a bit too fat,” and “much too fat”. The first two responses were combined into the category “too thin,” and the last two responses were combined into the category “too fat.” Extreme weight perceptions (“too thin” and “too fat”) were compared across countries by sex and age. A disproportionate concern over obesity was assessed with a ratio between the proportion of persons with BMI ≥85th percentile who perceived themselves as “too fat” and the proportion of persons with BMI ≤15th percentile who perceived themselves as “too thin.”

The fourth question, concerning weight control behavior, was formulated as: “At present are you on a diet or doing something else to lose weight?”. Possible responses were: “no, my weight is fine,” “no, because I need to put on weight,” “no, but I should lose some weight,” and “yes.”

Statistical analysis

Statistical data analyses were performed with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, version 13.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Mean BMI with 95% confidence intervals and cut-off points for 15th and 85th percentiles were calculated. χ2 tests were performed in order to test the sex, age, or country differences in prevalence for the variables. One-way ANOVA analysis (F test) with post hoc least significant difference test was conducted for testing the differences between mean BMI across countries. Where appropriate, t and z tests for independent samples were used as well. The level of significance was set at P<0.05.

Results

Knowledge about body weight and height

The response rates for both self-reported height and weight ranged from 78.3% to 98.9% (Table 1). Croatian adolescents were very well informed about their body weight (response rate ranged from 96.1% to 98.3% in different age and sex groups) and height (from 96.5% to 98.9%). Similarly, US respondents had a high response rate for reporting their body size measures. Their response rates ranged from 92.7% to 97.0% for weight and from 92.4% to 97.6% for height. Fewer Lithuanian respondents reported their body size data; from 81.2% to 87.9% reported their weight and from 79.3% to 92.6% reported their height. Consistently across countries, response rates for both height and weight values increased with age (except for reports on weight by Croatian respondents).

Table 1.

Adolescent self-reported height and weight by sex, age, and country

| Participants | No. | No. (%) of respondents who reported* |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| height | weight | ||

| Boys: | |||

| 13-y-old: | |||

| Lithuania | 954 | 685 (71.8) | 775 (81.2) |

| Croatia | 778 | 748 (96.1) | 765 (98.3) |

| United States | 894 | 788 (88.1) | 829 (92.7) |

| 15-y-old: | |||

| Lithuania | 981 | 803 (81.9) | 844 (86.0) |

| Croatia | 619 | 591 (95.5) | 604 (97.6) |

| United States | 754 | 697 (92.4) | 723 (95.9) |

| Girls: | |||

| 13-y-old: | |||

| Lithuania | 919 | 718 (78.1) | 759 (82.6) |

| Croatia | 713 | 682 (95.7) | 697 (97.8) |

| United States | 1027 | 894 (87.0) | 953 (92.8) |

| 15-y-old: | |||

| Lithuania | 923 | 796 (86.2) | 819 (88.7) |

| Croatia | 816 | 797 (97.7) | 807 (98.9) |

| United States | 871 | 829 (95.2) | 845 (97.0) |

*P<0.001 for both sexes and ages; χ2 test for comparison of reporting height and weight across countries.

Normative standards for body mass index

Means and cut-off points for BMI (at the 15th and 85th percentiles) in each country for 13- and 15-year-old boys and girls are provided in Table 2. All reported estimates were lowest in Lithuanian respondents in all sex and age groups. The US adolescents, particularly 15-year-olds, had the highest means and 85th percentiles of BMI. A significant increment of BMI values by age in all studied countries was observed (P<0.001, t test); however, they did not differ significantly between boys and girls.

Table 2.

Mean and the 15th and 85th percentiles of the body mass index in adolescents by sex, age, and country

| Participants | No. | Body mass index | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean (95% confidence interval)* | 15th percentile | 85th percentile | ||

| Boys: | ||||

| 13-y-old: | ||||

| Lithuania | 685 | 18.5 (18.3-18.6) | 16.2 | 20.8 |

| Croatia | 748 | 19.2 (19.0-19.4) | 16.6 | 21.9 |

| United States | 788 | 20.6 (20.4-20.9) | 16.9 | 24.7 |

| 15-y-old: | ||||

| Lithuania | 803 | 19.9 (19.8-20.1) | 17.8 | 22.1 |

| Croatia | 591 | 20.7 (20.5-21.0) | 18.0 | 23.7 |

| United States | 697 | 22.7 (22.4-23.0) | 18.9 | 27.1 |

| Girls: | ||||

| 13-y-old: | ||||

| Lithuania | 718 | 18.4 (18.2-18.6)† | 16.2 | 20.6 |

| Croatia | 682 | 18.9 (18.7-19.1)† | 16.5 | 21.5 |

| United States | 894 | 20.2 (20.0-20.4) | 16.9 | 23.8 |

| 15-y-old: | ||||

| Lithuania | 796 | 19.7 (19.5-19.8) | 17.3 | 21.8 |

| Croatia | 797 | 20.2 (20.0-20.4) | 17.8 | 22.6 |

| United States | 829 | 21.7 (21.4-21.9) | 18.3 | 25.5 |

*P<0.001 for both sexes and ages; F-ratio.

†P = 0.003 for this pair of means and P<0.001 for the remaining pairs of means, post hoc least statistical difference test in analysis of variance.

Perception of the body image

Prevalence in samples. Girls perceived themselves as being “too fat” more frequently and consistently across countries than boys (814 boys and 1741 girls, 19.7% vs 37.0%, P<0.001, z test). The prevalence of such perception increased with age among girls (748 among 13-year-olds and 993 among 15-year-olds, 32.7% vs 41.1%, P<0.001, z test) and decreased among boys (458 among 13-year olds and 356 among 15-year-olds, 21.4% vs 17.9%, P = 0.005, z test).

The lowest proportion of adolescents who perceived themselves as “too fat” was found in Lithuania; this proportion was markedly higher in Croatia and highest in the US (686 [24.2%], 773 [27.5%], and 1096 [34.3%] respondents; respectively, P<0.001, χ2 test). Such significant difference between countries existed in all sex and age groups (Table 3). The proportion of girls who perceived themselves as “too fat” was higher than the proportion of those who perceived themselves as “too thin,” but in boys this was noticed only in the US adolescents (both age groups) and Croatian 13-year-olds.

Table 3.

Prevalence of body image perception in adolescents by sex, age, and body mass index (BMI) in studied countries

| Sex | No. | No. (%) of respondents who reported being |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| too thin | about the right weight | too fat | P* | ||

| All BMI values:† | |||||

| Boys: | |||||

| 13-y-old: | 0.001 | ||||

| Lithuania | 616 | 95 (15.4) | 441 (71.6) | 80 (13.0) | |

| Croatia | 743 | 99 (13.3) | 479 (64.5) | 165 (22.2) | |

| United States | 782 | 116 (14.8) | 453 (57.9) | 213 (27.3) | |

| 15-y-old: | <0.001 | ||||

| Lithuania | 707 | 161 (22.8) | 489 (69.1) | 57 (8.1) | |

| Croatia | 591 | 111 (18.8) | 382 (64.6) | 98 (16.6) | |

| United States | 694 | 120 (17.3) | 373 (53.7) | 201 (29.0) | |

| Girls: | |||||

| 13-y-old: | 0.049 | ||||

| Lithuania | 716 | 79 (11.1) | 412 (57.5) | 225 (31.4) | |

| Croatia | 680 | 83 (12.2) | 397 (58.4) | 200 (29.4) | |

| United States | 889 | 91 (10.2) | 475 (53.4) | 32 (36.4) | |

| 15-y-old: | 0.003 | ||||

| Lithuania | 795 | 96 (12.0) | 375 (7.2) | 324 (40.8) | |

| Croatia | 796 | 104 (13.1) | 382 (48.0) | 310 (38.9) | |

| United States | 826 | 61 (7.4) | 406 (49.1) | 359 (43.5) | |

| BMI ≤15th percentile (underweight):† | |||||

| Boys: | |||||

| 13-y-old: | 0.549 | ||||

| Lithuania | 90 | 32 (35.6) | 55 (61.1) | 3 (3.3) | |

| Croatia | 111 | 41 (36.9) | 67 (60.4) | 3 (2.7) | |

| United States | 116 | 52 (44.8) | 59 (50.9) | 5 (4.3) | |

| 15-y-old: | 0.431 | ||||

| Lithuania | 99 | 44 (44.5) | 54 (54.5) | 1 (1.0) | |

| Croatia | 86 | 44 (51.2) | 41 (47.7) | 1 (1.1) | |

| United States | 108 | 55 (50.9) | 49 (45.4) | 4 (3.7) | |

| Girls: | |||||

| 13-y-old: | 0.713 | ||||

| Lithuania | 106 | 43 (40.6) | 56 (52.8) | 7 (6.6) | |

| Croatia | 105 | 48 (45.7) | 49 (46.7) | 8 (7.6) | |

| United States | 130 | 49 (37.7) | 73 (56.2) | 8 (6.1) | |

| 15-y-old: | 0.001 | ||||

| Lithuania | 112 | 48 (42.9) | 59 (52.7) | 5 (4.4) | |

| Croatia | 119 | 60 (50.4) | 52 (43.7) | 7 (5.9) | |

| United States | 125 | 33 (26.4) | 77 (61.6) | 15 (12.0) | |

| BMI ≥85th percentile (overweight):† | |||||

| Boys: | |||||

| 13-y-old: | <0.001 | ||||

| Lithuania | 96 | 6 (6.3) | 46 (47.9) | 44 (45.8) | |

| Croatia | 111 | 2 (1.8) | 36 (32.4) | 73 (65.8) | |

| United States | 116 | 1 (0.9) | 30 (25.9) | 85 (73.2) | |

| 15-y-old: | <0.001 | ||||

| Lithuania | 103 | 7 (6.8) | 75 (72.8) | 21 (20.4) | |

| Croatia | 89 | 2 (2.3) | 31 (34.8) | 56 (62.9) | |

| United States | 107 | 1 (0.9) | 18 (16.9) | 88 (82.2) | |

| Girls: | |||||

| 13-y-old: | 0.053 | ||||

| Lithuania | 105 | 0 (0) | 28 (26.7) | 77 (73.3) | |

| Croatia | 103 | 2 (1.9) | 27 (26.3) | 74 (71.8) | |

| United States | 132 | 1 (0.8) | 29 (22.0) | 102 (77.2) | |

| 15-y-old: | 0.093 | ||||

| Lithuania | 118 | 0 (0) | 22 (18.6) | 96 (81.4) | |

| Croatia | 121 | 2 (1.7) | 12 (9.9) | 107 (88.4) | |

| United States | 120 | 0 (0) | 21 (17.5) | 99 (82.5) | |

*χ2 test for comparison of adolescent body image perception across countries.

†BMI data were categorized into percentiles within sex and age group in each country sample separately.

Prevalence among the underweight. Few adolescents (percentage ranged from 1.0% for 15-year old Lithuanian boys to 7.6% for 13-year-old Croatian girls) with BMI≤15th percentile considered themselves as “too fat,” except 15-year-old US girls, among whom this proportion was much higher (12.0%). The proportion of adolescents who perceived themselves as “too thin” did not exceed 51.2%. A particularly low proportion of such adolescents was observed among US girls (37.7% and 26.4% in 13- and 15-year-olds, respectively). Sex and age differences in self-perception of body image were not consistent.

Prevalence among the overweight. Among adolescents with BMI ≥85th percentile, US boys tended to perceive themselves as “too fat” more often than boys from the other two countries (P<0.001). In contrast, the greatest degree of weight status underestimation was among Lithuanian boys. Girls perceived themselves as “too fat” more often than boys (P<0.05, with the exception of 15-year-olds in the US). The prevalence of self-perceptions as “too fat” increased with age among girls of all countries and among US boys.

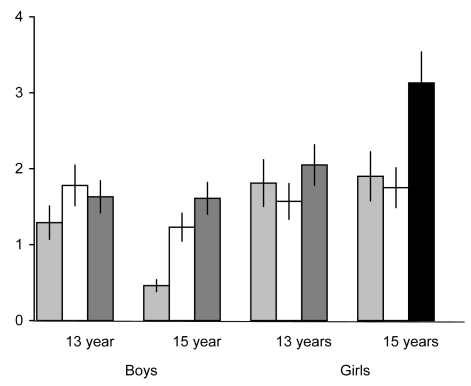

Across studied countries, the proportion of adolescents with BMI ≥85th percentile who perceived themselves as “too fat” was significantly greater than the proportion of adolescents with BMI ≤15th percentile who perceived themselves as “too thin” (with the exception of 15-year-old Lithuanian boys). The most striking contrast between these proportions (ratio equal 3.13) was observed among US girls aged 15 years (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A ratio between perceptions of being “too fat” among adolescents with body mass index (BMI) ≥85th percentile and perception of being “too thin” among adolescents with BMI ≤15th percentile. Open bars – Croatia; gray bars – Lithuania; closed bars – United States; vertical lines – 95% confidence interval.

Weight control efforts

Prevalence of weight control in samples. Girls reported more frequently than boys that they were on a diet or doing something else to lose weight (390 boys and 891 girls, 9.1% vs 18.9%, P<0.001, z test). Girls also reported more frequently than boys that they should lose weight even if they were making no efforts to do so (608 boys and 1412 girls, 14.1% vs 30.0%, P<0.001, z test). In contrast, a wish to put on weight was more frequent in boys (722 boys and 443 girls, 16.8% vs 9.4%, P<0.001, z test).

Cross-country comparisons (Table 4) indicated that dieting and other methods of losing weight were most prevalent in the US adolescents, while Lithuanian adolescents were least likely to diet, considering their body weight to be normal. The prevalence of such efforts increased with age in girls from all countries and in boys from the US only.

Table 4.

Prevalence of weight control efforts by sex, age, and body mass index (BMI) in adolescents in the studied countries*

| Sex | No. | No. (%) of respondents who reported being on a diet or doing something else to lose weight | P* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| no, normal weight | no, need to put on weight | no, but should lose some weight | yes | ||||

| All BMI values:† | |||||||

| Boys: | |||||||

| 13-y-old: | <0.001 | ||||||

| Lithuania | 684 | 482 (70.5) | 108 (15.8) | 60 (8.7) | 34 (5.0) | ||

| Croatia | 741 | 412 (55.6) | 126 (17.0) | 162 (21.9) | 41 (5.5) | ||

| United States | 788 | 485 (61.5) | 73 (9.3) | 118 (15.0) | 112 (14.2) | ||

| 15-y-old: | <0.001 | ||||||

| Lithuania | 803 | 528 (65.8) | 183 (22.8) | 58 (7.2) | 34 (4.2) | ||

| Croatia | 591 | 335 (56.7) | 121 (20.5) | 109 (18.4) | 26 (4.4) | ||

| United States | 694 | 339 (48.8) | 111 (16.0) | 101 (14.6) | 143 (20.6) | ||

| Girls: | |||||||

| 13-y-old: | <0.001 | ||||||

| Lithuania | 715 | 346 (48.4) | 76 (10.6) | 201 (28.1) | 92 (12.9) | ||

| Croatia | 682 | 316 (46.3) | 82 (12.0) | 231 (33.9) | 53 (7.8) | ||

| United States | 890 | 444 (49.9) | 54 (6.1) | 179 (20.1) | 213 (23.9) | ||

| 15-y-old: | <0.001 | ||||||

| Lithuania | 796 | 307 (38.6) | 84 (10.6) | 242 (30.4) | 163 (20.4) | ||

| Croatia | 797 | 266 (33.4) | 94 (11.8) | 313 (39.3) | 124 (15.5) | ||

| United States | 828 | 283 (34.2) | 53 (6.4) | 246 (29.7) | 246 (29.7) | ||

| BMI ≤15th percentile (underweight):† | |||||||

| Boys: | |||||||

| 13-y-old: | 0.071 | ||||||

| Lithuania | 101 | 73 (72.3) | 27 (26.7) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.0) | ||

| Croatia | 111 | 59 (53.2) | 45 (40.5) | 5 (4.5) | 2 (1.8) | ||

| United States | 118 | 77 (65.3) | 34 (28.8) | 5 (4.2) | 2 (1.7) | ||

| 15-y-old: | 0.077 | ||||||

| Lithuania | 119 | 74 (62.2) | 43 (36.2) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.8) | ||

| Croatia | 86 | 37 (43.0) | 46 (53.5) | 1 (1.2) | 2 (2.3) | ||

| United States | 107 | 60 (56.1) | 40 (37.3) | 2 (1.9) | 5 (4.7) | ||

| Girls: | |||||||

| 13-y-old: | 0.001 | ||||||

| Lithuania | 107 | 64 (59.8) | 35 (32.7) | 5 (4.7) | 3 (2.8) | ||

| Croatia | 105 | 49 (46.7) | 46 (43.8) | 7 (6.7) | 3 (2.8) | ||

| United States | 130 | 87 (66.9) | 25 (19.2) | 6 (4.6) | 12 (9.3) | ||

| 15-y-old: | <0.001 | ||||||

| Lithuania | 112 | 60 (53.6) | 43 (38.3) | 6 (5.4) | 3 (2.7) | ||

| Croatia | 119 | 50 (42.0) | 53 (44.5) | 12 (10.1) | 4 (3.4) | ||

| United States | 125 | 69 (55.2) | 28 (22.4) | 13 (10.4) | 15 (12.0) | ||

| BMI ≥85th percentile (overweight):† | |||||||

| Boys: | |||||||

| 13-y-old: | <0.001 | ||||||

| Lithuania | 106 | 55 (51.9) | 6 (5.7) | 34 (32.1) | 11 (10.3) | ||

| Croatia | 112 | 35 (31.3) | 4 (3.6) | 54 (48.1) | 19 (17.0) | ||

| United States | 119 | 28 (23.5) | 2 (1.7) | 42 (35.3) | 47 (39.5) | ||

| 15-y-old | <0.001 | ||||||

| Lithuania | 120 | 69 (57.5) | 11 (9.2) | 31 (25.8) | 9 (7.5) | ||

| Croatia | 89 | 29 (32.6) | 2 (2.2) | 48 (53.9) | 10 (11.3) | ||

| United States | 107 | 11 (10.3) | 2 (1.9) | 38 (35.5) | 56 (52.3) | ||

| Girls | |||||||

| 13-y-old: | 0.062 | ||||||

| Lithuania | 105 | 15 (14.3) | 0 (0) | 61 (58.1) | 29 (27.6) | ||

| Croatia | 103 | 16 (15.5) | 1 (1.0) | 65 (63.1) | 21 (20.4) | ||

| United States | 133 | 20 (15.0) | 0 (0) | 62 (46.6) | 51 (38.4) | ||

| 15-y-old: | 0.003 | ||||||

| Lithuania | 118 | 11 (9.4) | 1 (0.8) | 66 (55.9) | 40 (33.9) | ||

| Croatia | 121 | 6 (5.0) | 0 (0) | 77 (63.6) | 38 (31.4) | ||

| United States | 121 | 5 (4.1) | 1 (0.8) | 49 (40.5) | 66 (54.6) | ||

*χ2 test for comparison of weight control efforts across countries.

†BMI data were categorized into percentiles within sex and age groups in each country sample separately.

Prevalence of weight control in the underweight. As expected, adolescents with BMI ≤15th percentile less frequently reported attempts to lose weight; however 9.3% to 12.0% of US girls in this weight category reported being on a diet or doing something else to lose weight.

Prevalence of weight control in the overweight. The highest proportion of adolescents with BMI ≥85th percentile who were on a diet or doing something else to lose weight was found in the US. Across all countries, 15-year-old girls were more likely to report weight control efforts than 13-year-old girls. Among boys, this age difference was observed in US respondents only. In addition, Lithuanian boys were most satisfied with their weight, regardless of their weight status.

Discussion

Our study showed that body image and weight control behavior differed among adolescents in Lithuania, Croatia, and the US, and that they were influenced by age and sex. Country differences might be related to the already described disparity in overweight prevalence among adolescents of the selected countries. Recent analyses of HBSC data (13,14,17) showed that the US had the highest, Lithuania the lowest, and Croatia medium prevalence of overweight adolescents.

In accordance with other studies, girls in all countries more often perceived themselves as overweight than boys despite their real overweight (17-20). This confirms that girls are more concerned about their body weight and image than boys. The major theories of body image suggest that women and men perceive their bodies in a different way (12). The ideal of male beauty is a strong muscular body, as opposed to a slim figure, which is an ideal for women (21).

We categorized BMI into percentiles within each sex, age, and country sample. On the basis of this we could be sure that participants with BMI ≤15th percentile were among the thinnest in their country, while those with BMI ≥85th percentile were the fattest. This allowed us to compare the perceptions of body image and weight loss behavior in groups of underweight and overweight adolescents and investigate how these were influenced by sex and age.

It is logical to hypothesize that a disproportionate prevalence of adolescents with BMI in the overweight range would lead to an increase in negative body image. However, when perceptions of body weight were examined more closely, it appeared that not only a proportion of underweight adolescents did not perceive themselves as thin, but also that they perceived themselves as overweight, regardless of their actual BMI or their BMI relative to other adolescents within their country. Similar discrepancy, which is more marked in adolescent girls, was also established by researchers in Asian cultures (20).

One possible explanation for over- or under-estimation of weight status is social and cultural context, which plays a significant role in the development of perceptions. Our data showed that overweight adolescents from the US, where the prevalence of overweight and obesity is particularly high, were more worried about the problem than those in “slimmer” populations – Lithuania or Croatia. On the other hand, similar overweight body image among Lithuanian and Croatian overweight girls suggest that, perhaps, the beauty ideal of slimness prevails among girls in all three countries. A cross-sectional study found that acceptance of societal standards regarding thinness contributed to a development of eating disorders in Croatian girls (22).

Within cultures, however, there are variations in the ideal of beauty. Still, cultural pressure seems to be central factor influencing body shape in modern adolescents worldwide. A recent study concluded that adolescents’ perception of being overweight was more related to body dissatisfaction than actual body size (23).

With the rapidly increasing prevalence of obesity in youth, we were particularly interested in weight control behavior among adolescents. This study corroborates findings of other studies, confirming that overweight adolescents engage in dieting more often than underweight adolescents (20). The obsession with thinness was prevalent in all countries. Our results suggest that a significant proportion of adolescents engaged in weight control when it was not necessary. Across all countries, a substantial percentage of adolescents were thinking about weight control. This leads to a hypothesis that dieting could be considered as a marker of other unhealthy behaviors and depressed mood in adolescence (9). Our findings support the idea that weight-loss behavior may continue to increase in adolescents.

In addition, an interesting finding of our study was that overweight Lithuanian boys feel most comfortable with their weight than other boys. This finding correlates with the fact that Lithuanian adolescents were least aware of their body height and weight. Further examination showed that perception of being too fat was an argument for dieting in all our respondents, except in boys in Lithuania. Another explanation for an increased interest in weight loss in boys is that they are affected by peer, mass media, or other cultural body image stereotypes and tend to increase and demonstrate their muscles rather than only to lose their weight (20).

Strengths of the current study include the nationally-representative samples and relatively high participation rates. This study also has some limitations. First, it is possible that the interpretation of BMI results could be biased by self-reported weight and height; however, other studies have shown that self-reports are reliable in adolescents (24-27). To deal with potential bias in self-reported weight and height, we used sex, age, and country-specific percentiles rather than the absolute criteria of overweight.

The second limitation of our study were missing data on weight and height among Lithuanian respondents. As some validity studies demonstrated, adolescents who did not want to report their height and weight were more likely to be overweight (27). To investigate this hypothesis, we compared body perceptions and weight loss attempts between the adolescents in Lithuania who reported their weight and height with those who did not. We found the same rates in both groups. This indicates that the lower response rate among Lithuanian adolescents did not affect the representativeness of the sample and validity of the study.

The third limitation of this study is a lack of globally recognized criteria for overweight and especially for underweight during puberty. To overcome this methodological problem, the method of categorizing BMI values into percentiles in each country sample was used. Therefore, we compared our 85th percentile cut-off points for establishing overweight with international survey criteria (defined as body mass index of 25 kg/m2 at the age of 18), which were presented by Cole et al (28). International cut-off points for BMI for overweight were 21.91 for boys and 22.58 for girls at the age of 13 and 23.29 and 23.94, respectively, at the age of 15. These cut-off points were very close to the 85th percentile of BMI estimated for Croatian children aged 13 and 15 in our study. This confirms that it was correct to choose the 85th percentile for defining overweight and supports the status of Croatia as a country with a medium overweight prevalence in adolescents.

Our findings indicate the need for more comprehensive studies of obesity, as it becomes a common problem in adolescents. Since in our study motivations for weight control behavior were not assessed, dieting behavior of adolescents might differ from supervised weight loss programs in the country. Also, the observed sex and age differences across countries stimulate an interest in factors that moderate such differences.

In conclusion, body image and weight control behavior differ among adolescents in Lithuania, Croatia, and the US. Consistently across countries, girls were more likely to perceive themselves as overweight and were trying to lose weight, while the pattern among boys was more variable. The highest rates of perception of overweight and weight loss efforts were established among US adolescents, where obesity has reached epidemic proportions (13,14). Except for 15-year-old Lithuanian boys, adolescents overestimated their status as overweight and underestimated their status as thin.

Acknowledgment

The Health Behaviour in School-aged Children project is a World Health Organization (EURO) collaborative study. International Coordinator of the 2001/2002 study was Candace Currie, University of Edinburgh, Scotland; while Data Bank Manager was Oddrun Samdal, University of Bergen, Norway. Principal investigators in the three countries were: Croatia (Marina Kuzman), Lithuania (Apolinaras Zaborskis), and USA (Mary Overpeck).

References

- 1.Lobstein T, Baur L, Uauy R. IASO International Obesity TaskForce. Obesity in children and young people: a crisis in public health. Obes Rev. 2004;5(Suppl 1):4–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2004.00133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Hannan PJ, Perry CL, Irving LM. Weight-related concerns and behaviors among overweight and nonoverweight adolescents: implications for preventing weight-related disorders. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:171–8. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.2.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paxton SJ, Eisenberg ME, Neumark-Sztainer D. Prospective predictors of body dissatisfaction in adolescent girls and boys: a five-year longitudinal study. Dev Psychol. 2006;42:888–99. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Strong KG, Huon GF. An evaluation of a structural model for studies of the initiation of dieting among adolescent girls. J Psychosom Res. 1998;44:315–26. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(97)00257-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strauss RS. Self-reported weight status and dieting in a cross-sectional sample of young adolescents: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153:741–7. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.7.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krowchuk DP, Kreiter SR, Woods CR, Sinal SH, DuRant RH. Problem dieting behaviors among young adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1998;152:884–8. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.152.9.884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stice E, Cameron RP, Killen JD, Hayward C, Taylor CB. Naturalistic weight-reduction efforts prospectively predict growth in relative weight and onset of obesity among female adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67:967–74. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.67.6.967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Field AE, Austin SB, Taylor CB, Malspeis S, Rosner B, Rockett HR, et al. Relation between dieting and weight change among preadolescents and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2003;112:900–6. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.4.900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crow S, Eisenberg ME, Story M, Neumark-Sztainer D. Suicidal behavior in adolescents: relationship to weight status, weight control behaviors, and body dissatisfaction. Int J Eat Disord. 2008;41:82–7. doi: 10.1002/eat.20466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Dea JA. Self-concept, self-esteem and body weight in adolescent females: a three-year longitudinal study. J Health Psychol. 2006;11:599–611. doi: 10.1177/1359105306065020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bacchini D, Magliulo F. Self-image and perceived self-efficacy during adolescence. J Youth Adolesc. 2003;32:337–49. doi: 10.1023/A:1024969914672. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morrison TG, Kalin R, Morrison MA. Body-image evaluation and body-image investment among adolescents: a test of sociocultural and social comparison theories. Adolescence. 2004;39:571–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Janssen I, Katzmarzyk PT, Boyce WF, Vereecken C, Mulvihill C, Roberts C, et al. Comparison of overweight and obesity prevalence in school-aged youth from 34 countries and their relationships with physical activity and dietary patterns. Obes Rev. 2005;6:123–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2005.00176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lissau I, Overpeck MD, Ruan WJ, Due P, Holstein BE, Hediger ML, et al. Body mass index and overweight in adolescents in 13 European countries, Israel, and the United States. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158:27–33. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roberts C, Currie C, Samdal O, Currie D, Smith R, Maes L. Measuring the health and health behaviours of adolescents through cross-national survey research: recent developments in the Health Behavior in School-aged Children (HBSC) study. J Public Health (Bangkok). 2007;15:179–86. doi: 10.1007/s10389-007-0100-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Currie C, Samdal O, Boyce W, Smith B, editors. Health behaviour in school-aged children: a WHO cross-national study. Research protocol for the 2001/2002 survey. Edinburgh (UK):Child and Adolescent Health Research Unit, University of Edinburgh; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Currie C, Roberts C, Morgan A, Smith R, Settertobulte W, Samdal O, et al, editors. Young people’s health in context. Health behaviour in school-aged children (HBSC) study: international report from the 2001/2002 survey. Copenhagen: World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barker ET, Galambos NL. Body dissatisfaction of adolescent girls and boys: risk and resource factors. J Early Adolesc. 2003;23:141–65. doi: 10.1177/0272431603023002002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bearman SK, Martinez E, Stice E, Presnell K. The skinny on body dissatisfaction: a longitudinal study of adolescent girls and boys. J Youth Adolesc. 2006;35:217–29. doi: 10.1007/s10964-005-9010-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheung PC, Ip PL, Lam ST, Bibby H. A study on body weight perception and weight control behaviours among adolescents in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J. 2007;13:16–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCabe MP, Ricciardelli LA. A prospective study of pressures from parents, peers, and the media on extreme weight change behaviors among adolescent boys and girls. Behav Res Ther. 2005;43:653–68. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rukavina T, Pokrajac-Bulian A. Thin-ideal internalization, body dissatisfaction and symptoms of eating disorders in Croatian adolescent girls. Eat Weight Disord. 2006;11:31–7. doi: 10.1007/BF03327741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Halliwell E, Harvey M. Examination of a sociocultural model of disordered eating among male and female adolescents. Br J Health Psychol. 2006;11:235–48. doi: 10.1348/135910705X39214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elgar FJ, Roberts C, Tudor-Smith C, Moore L. Validity of self-reported height and weight and predictors of bias in adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2005;37:371–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Himes JH, Faricy A. Validity and reliability of self-reported stature and weight of US adolescents. Am J Hum Biol. 2001;13:255–60. doi: 10.1002/1520-6300(200102/03)13:2<255::AID-AJHB1036>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fonseca H, Gaspar de Matos M. Perception of overweight and obesity among Portuguese adolescents: an overview of associated factors. Eur J Public Health. 2005;15:323–8. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cki071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brener ND, Mcmanus T, Galuska DA, Lowry R, Wechsler H. Reliability and validity of self-reported height and weight among high school students. J Adolesc Health. 2003;32:281–7. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(02)00708-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM, Dietz WH. Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: international survey. BMJ. 2000;320:1240–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7244.1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]