Abstract

Recent studies have identified vimentin, a type III intermediate filament, among genes differentially expressed in tumours with more invasive features, suggesting an association between vimentin and tumour progression. The aim of this study, was to investigate whether vimentin expression in colon cancer tissue is of clinical relevance. We performed immunostaining in 142 colorectal cancer (CRC) samples and quantified the amount of vimentin expression using computer-assisted image analysis. Vimentin expression in the tumour stroma of CRC was associated with shorter survival. Overall survival in the high vimentin expression group was 71.2% compared with 90.4% in the low-expression group (P=0.002), whereas disease-free survival for the high-expression group was 62.7% compared with 86.7% for the low-expression group (P=0.001). Furthermore, the prognostic power of vimentin for disease recurrence was maintained in both stage II and III CRC. Multivariate analysis suggested that vimentin was a better prognostic indicator for disease recurrence (risk ratio=3.5) than the widely used lymph node status (risk ratio=2.2). Vimentin expression in the tumour stroma may reflect a higher malignant potential of the tumour and may be a useful predictive marker for disease recurrence in CRC patients.

Keywords: colorectal cancer, vimentin, prognosis

Intermediate filament proteins form a dynamic cytoskeletal network in the cell to protect them against mechanical stress and to maintain cellular integrity (Clarke and Allan, 2002; Helfand et al, 2004). Vimentin is a type III intermediate filament characteristically found in cells of mesenchymal origin, that is fibroblast, chondrocytes, macrophages, and endothelial cells (Osborn, 1983). Vimentin was postulated to act as a scaffolding protein to stabilise connective tissues and cells, or in signal transduction (Herrmann et al, 2003; Eriksson et al, 2004). It was also reported to be involved in wound healing (Eckes et al, 2000) and lipid metabolism (Schweitzer and Evans, 1998).

Recently, an association between vimentin and tumour development, progression, and chemosensitivity was suggested by various gene profiling studies (Zajchowski et al, 2001; Mellick et al, 2002; Penuelas et al, 2005). Vimentin was selectively overexpressed in highly aggressive breast cancer cells (Zajchowski et al, 2001). It was also included, along with eight other genes, in a test that could sufficiently distinguish between invasive and noninvasive breast cancer (Nagaraja et al, 2006). Expression studies also indicated that vimentin overexpression in prostate cancer correlates with a more malignant phenotype (Lang et al, 2002; Singh et al, 2003). Furthermore, proteomic analysis identified the vimentin gene as one differentially expressed in colorectal cancer compared with the surrounding normal tissue (Alfonso et al, 2005). In regard to chemosensitivity, vimentin expression was higher in colon carcinoma cell clones resistant to doxorubicin, although vimentin alone did not confer resistance (Conforti et al, 1995). Similar findings were reported for a multidrug resistant breast cancer subline (Bichat et al, 1997).

In this study, we evaluated the significance of vimentin expression in colorectal cancer (CRC). Although colon cancer cells did not express vimentin, we found that stromal vimentin expression was quite abundant. Tumour stromal reaction is known to be dynamic. Difficulties in quantifying changes in the tumour stroma have limited the possibility of its utilisation in clinical settings. Here, we attempted semiquantification using computer-assisted imaging, and further analysed the correlation to clinicopathological factors and patients' survival.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

Vimentin expression was examined in a total of 142 CRC tissues of intermediate stages, that is, stage II (n=78) and stage III (n=63), based on the UICC TNM classification. The mean age of the patients was 62.5±9.5 years, with 62 women and 80 men. The tumours ranged in size from 0.8±12.0 cm (mean 5.1±1.8 cm), and were resected from either the colon (n=80) or rectum (n=62). The mean follow-up period was 66.1±29.4 months (range, 0.72–150.0 months). The overall 5-year survival rate was 82.4% and the 5-year disease-free survival rate was 76.8%. After surgery, stage III patients received 5-FU-based chemotherapy. Patients with stage II CRC had no chemotherapy unless the patient requested it. The study protocol was approved by the Human Ethics Review Committee of the Graduate School of Medicine, Osaka University.

Histology

Tissue sections (4 μm thick) were prepared from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded blocks. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) solution, and reviewed by two pathologists from the Department of Pathology, Osaka University. The histological staging of tumours was as follows: well-differentiated adenocarcinoma (n=72), moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma (n=59), poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma (n=5), mucinous carcinoma (n=5), and signet ring cell carcinoma (n=1). The extent of stromal reaction was evaluated as extensive, moderate, and slight according to the criteria reported (Jass et al, 1986; Harrison et al, 1994). Tumour budding was evaluated based on the definition reported previously, and classified as high-grade budding and low-grade budding accordingly (Ueno et al, 2002). Characteristics of the tumour at the invasive margin were evaluated based on the diffuse infiltrative features of the tumour (Jass et al, 1987).

Immunohistochemistry

Expression of vimentin was studied by immunohistochemistry. Immunostaining was performed using the Vectastain ABC peroxidase kit (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA, USA), as described previously by our laboratories (Noura et al, 2002; Yamamoto et al, 2003). Tissues were sliced into 4 μm sections, dewaxed in xylene, and rehydrated in decreasing concentrations of ethanol. Sections were subjected to endogenous peroxidase blocking in 1% H2O2 solution in methanol for 20 min and then to antigen retrieval treatment in 10 mM citrate buffer, pH 6.0, for 40 min in a water bath preheated to 95°C. Serum blocking was performed using 10% normal rabbit serum for 30 min at room temperature. This was followed by incubation with primary antibodies at 4°C overnight. Both the anti-vimentin (Novocastra, Newcastle, UK) and anti-proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) (PC10, Novocastra) monoclonal antibodies were diluted 1 : 50. Anti-CD34 (Novocastra) was used at 1 : 500 dilution. PCNA labelling was included as a quality control of tissue blocks. Secondary biotinylated anti-mouse antibody (BA2000, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) was used at a dilution of 1 : 100 for 30 min at room temperature. Washing was performed using phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Reaction product was visualised using 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Osaka, Japan) as a chromogenic substrate. Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated, and mounted. For the negative control, nonimmunised mouse IgG (Vector Labs) was used in place of the primary antibodies.

Computer-assisted imaging

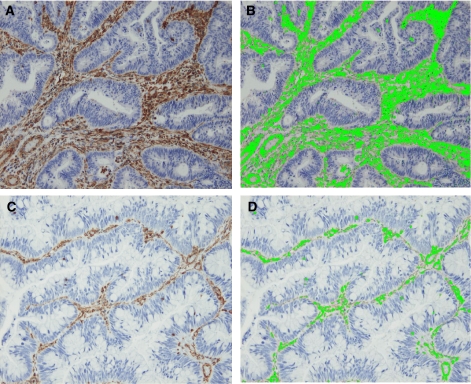

The stained sections were viewed under a microscope equipped with a charge-coupled device (CCD) colour camera (Olympus Corp., Tokyo, Japan). We selected 10 fields in the ‘hot spots’ of positivity in each specimen at high power magnification. Photos were analysed using imaging processor Mac SCOPE software (Mitani Corp., Fukui, Japan), where the staining area (Figure 1) was calculated accordingly. Briefly, the investigator selected the brown-stained areas representative of vimentin expression on the photo. Vimentin expression in the colonic mucosal lymphocytes was used as internal positive control. The computer would then automatically detect the area with the same configuration on the photo and convert the data to a percentage of the total area in each field.

Figure 1.

Representative sections of high vimentin expression (A) and low vimentin expression (C) in tumour stroma. Images were analysed based on the colour selection. Image analysis figures are shown (B and D). Area labelled (in fluorescent green) was calculated accordingly. Surface area was calculated as 22.0 and 3.3%.

Statistical analysis

Mean values were compared using the Student's t-test. Associations between discrete variables were assessed using the χ2 test. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to estimate tumour recurrence or death from CRC, and the log-rank test was used to examine statistical significance. A Cox proportional hazards model was used to assess the risk ratio under simultaneous contributions from several covariates. All statistical analyses were performed using the StatView J-5.0 programme (Abacus Concepts Inc., Berkeley, CA, USA). All data were expressed as the mean±s.d.. P-values of less than 0.05 were accepted as statistically significant.

RESULTS

Expression of vimentin in CRC tissue

Vimentin expression was detected in the tumour stroma region (Figure 1). Staining was intense and homogenous. No expression was observed in the normal colonic epithelial cells or tumour cells. Using computer-assisted image analysis, vimentin scores were determined (Figure 1). When 10 fields were analysed, vimentin expression varied widely, ranging from 1.7 to 24.1% (mean 8.8±4.3%). The quality of all tissue blocks was confirmed by intense staining for PCNA in the proliferative zone of normal colonic epithelium and germinal centres of lymphoid follicles.

Vimentin expression and clinicopathological characteristics

Using the mean value of vimentin expression, 8.8%, as a cutoff point, the sample population was divided into high-expression (n=59) and low-expression groups (n=83). When vimentin expression was compared with the clinicopathological parameters listed in Table 1, an association was found between vimentin expression and age. Other factors were not associated with vimentin expression.

Table 1. Vimentin expression and patient characteristics.

|

Vimentin expression

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinicopathological characteristic | High | Low | P -value |

| Age | 64.4±8.6 | 61.1±9.9 | 0.037 |

| Tumour size | 0.3±2.0 | 5.0±1.7 | 0.348 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 32 | 48 | 0.670 |

| Female | 27 | 35 | |

| Tumour site | |||

| Colon | 36 | 44 | 0.343 |

| Rectum | 23 | 39 | |

| Degree of differentiation | |||

| Well | 27 | 45 | 0.321 |

| Mod./poor | 32 | 38 | |

| Depth of invasion | |||

| mp | 5 | 8 | 0.812 |

| ss | 54 | 75 | |

| Lymph node metastasis | |||

| Absent | 28 | 51 | 0.098 |

| Present | 31 | 32 | |

| No of lymph nodes involved | |||

| 0 | 28 | 51 | 0.167 |

| 1–3 | 20 | 24 | |

| ⩾4 | 11 | 8 | |

| Lymphovascular invasion a | |||

| Absent | 24 | 32 | 0.799 |

| Present | 35 | 51 | |

Well=well-differentiated adenocarcinoma, Mod.=moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma, Poor=poorly differentiated carcinoma (this category included five cases of poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, five cases of mucinous carcinoma and one case of signet ring cell carcinoma), mp=muscularis propria; ss=subserosa.

Lymphatic invasion was determined by the presence of tumour cells in lymphatic ducts. Bold value is statistically significant (P<0.05).

Vimentin expression and histological characteristics at the tumour–stroma interface

Changes in the stroma may have an active role in the acquisition of invasive phenotype of tumour cells. We tested whether vimentin expression is associated with these histological characteristics at the tumour–stroma interface.

Tumours displaying diffuse infiltration pattern at the invasive front are deemed to be more aggressive. In this series, the 52.8% of the tumours exhibited this feature whereas the remaining 47.2% of the tumours lacked this feature. No association between this feature and vimentin expression was found.

Tumour budding was another histological change noted at the invasive front. This histological dedifferentiation phenomenon was observed in immature stroma, possibly promoting tumour progression (Ueno et al, 2004). Of the 142 CRC cases, only 27 (19.0%) showed high-grade tumour budding and the remaining 115 (81.0%) showed low-grade tumour budding. No significant association was found between tumour budding and vimentin expression.

We also compared vimentin expression with the extent of stromal response. In this series of CRCs, 24 tumours (16.9%) showed extensive stromal response, 95 (66.9%) showed moderate response, and 23 (16.2%) showed a slight response. No association was noted between this response and vimentin expression.

Survival analysis

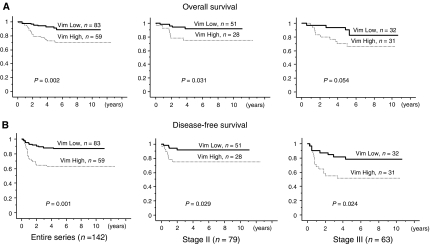

For the overall and disease-free survival analysis, high vimentin expression was significantly associated with a shorter survival. For overall survival (Figure 2A), 5-year survival for the high-expression group was 71.2% compared with 90.4% for the low-expression group (P=0.002). Similarly, as shown in Figure 2B, the 5-year disease-free survival rate was 62.7% for the high-expression group compared with 86.7% in the low-expression group (P=0.001). When we further analysed the survival data for stage II (without lymph node metastasis) and stage III (with lymph node metastasis) CRC, we found that irrespective of the lymph node status, vimentin expression was significantly associated with a higher disease recurrence rate (Figure 2B). For stage II tumours, the disease-free survival rate for the high vimentin expression group was 71.4% compared with 92.3% in the low-expression group (P=0.029). Meanwhile, for stage III tumours, the disease-free survival for the high-expression group was 45.2% compared with 79.4% in the low-expression group (P=0.024). However, for overall survival (Figure 2A), an association was found only in stage II (75.0 vs 92.2%, P=0.031), but not in stage III (67.7 vs 87.5%, P=0.054). Considering that disease recurrence may provide a better understanding of clinical prognosis, further analyses were performed based on disease recurrence rather than overall survival (Andre et al, 2004).

Figure 2.

Survival curves were plotted using the Kaplan–Meier method for high vimentin (Vim High) expression and low (Vim Low) expression groups. (A) Overall survival. (B) Disease-free survival. Both end points were further analysed according to tumour staging (stages II and III).

Univariate survival analyses for other clinicopathological parameters and a few histological characteristics at tumour–stroma interface are summarised in Table 2. Of all parameters, lymph node metastasis status was of prognostic value, as expected. No other parameters showed significant prognostic value. Multivariate analysis of vimentin expression and other histopathological factors (Table 3) revealed that vimentin was an independent prognostic factor for CRC disease recurrence, with the high-expression group having a 3.5-fold greater risk of recurrence compared with the low-expression group. The risk ratio was also higher compared with lymph node status (relative risk of 2.2-fold). In addition, the diffuse infiltration characteristic at the invasive front was also shown to be an independent prognostic factor with a relative risk of 2.3-fold.

Table 2. Univariate survival analysis (disease-free survival).

| Characteristics | Category | n | 5-year survival | P -value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vimentin | <8.8% | 83 | 86.7 | 0.001 |

| ⩾8.8% | 59 | 62.7 | ||

| Age (years) | <62 | 64 | 76.7 | 0.986 |

| ⩾62 | 78 | 76.9 | ||

| Tumour size (cm) | ⩾5.1 | 71 | 76.1 | 0.881 |

| <5.1 | 71 | 77.5 | ||

| Gender | Male | 80 | 78.8 | 0.631 |

| Female | 62 | 74.2 | ||

| Tumour site | Colon | 80 | 73.8 | 0.420 |

| Rectum | 62 | 80.7 | ||

| Degree of differentiation | Well | 72 | 80.6 | 0.292 |

| Mod./poor | 70 | 72.9 | ||

| Depth of invasion | mp | 13 | 69.2 | 0.376 |

| ss | 129 | 77.5 | ||

| Lymph node metastasis | Absent | 79 | 86.1 | 0.004 |

| Present | 63 | 65.1 | ||

| Lymphovascular invasiona | Absent | 56 | 80.4 | 0.291 |

| Present | 86 | 74.4 | ||

| Diffuse infiltration | Absent | 67 | 83.6 | 0.051 |

| Present | 79 | 70.7 | ||

| Tumour budding | Low grade (<10) | 120 | 75.0 | 0.238 |

| High grade (⩾10) | 22 | 86.4 | ||

| Stromal reaction | Extensive | 24 | 75.0 | 0.884 |

| Moderate/slight | 118 | 77.1 |

mp=muscularis propria; ss=subserosa.

Lymphatic invasion was determined by the presence of tumour cells in lymphatic ducts. Bold values are statistically significant (P<0.05).

Table 3. Multivariate analysis (disease-free survival).

| P-value | Risk ratio | Confidence interval | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vimentin (high: low) | 0.001 | 3.45 | 1.65–7.22 |

| Lymphovascular invasion (present: absent) | 0.567 | 1.24 | 0.59–2.62 |

| Diffuse infiltration (present: absent) | 0.047 | 2.29 | 1.01–5.18 |

| Tumour budding (high grade: low grade) | 0.340 | 0.62 | 0.24–1.65 |

| Lymph node metastasis (present: absent) | 0.043 | 2.20 | 1.02–4.72 |

| Depth of invasion (ss: mp) | 0.445 | 0.64 | 0.20–2.02 |

| Stromal reaction (extensive: moderate/slight) | 0.875 | 1.08 | 0.42–2.78 |

Vimentin expression and microvascular density

Endothelial cells also display reactivity to anti-vimentin antibody. Therefore, we also evaluated endothelial cells using antibody against CD34. The total area stained for CD34 ranged from 0.09 to 2.42%, with a mean of 0.82%. CD34 staining accounted for less than 10% of the area staining for vimentin. We re-examined the prognostic value of vimentin expression after deducting the total area staining for CD34 to test whether microvascular density contributed to the prognostic significance of vimentin. Using the average mean value (7.96%) of vimentin after this adjustment as a cutoff point, a statistically significant difference (P=0.008) was still observed between the high-and low-expression groups.

DISCUSSION

Tissue stroma consists of a variety of matrix substances such as interstitial collagen, fibronectin, elastin, and glycoaminoglycans and a variety of cell types including inflammatory cells, immune cells, fibroblasts, muscle, and vascular cells (Dvorak, 1986). Stromal microenvironment in tumour has a crucial role in tumour progression. It provides an interface between malignant cells and host tissues (Bissell and Radisky, 2001). Cumulative evidence suggests that the balance of host–tumour interdependency could modulate the phenotype of a tumour, and thus influence the outcome of the disease. However, appropriate markers to quantify the stromal reaction have yet to be determined.

Vimentin is ubiquitously expressed by cells of mesenchymal origin including fibroblasts, endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, leucocytes, and some other cells (Dulbecco et al, 1983; Mor-Vaknin et al, 2003). In certain carcinomas such as breast cancer or melanoma, vimentin was upregulated in aggressive phenotypes in a phenomenon known as epithelial–mesenchymal transition (Brabletz et al, 2005). However, this phenomenon was not observed in CRC. In fact, in CRC, vimentin was specifically expressed in the stroma, but not in the tumour cells (Altmannsberger et al, 1982; von Bassewitz et al, 1982; Sordat et al, 2000). Thus, in this study we attempted to quantitate the expression of vimentin to verify the clinical value of the stromal response in CRC.

We found that vimentin expression in the tumour stroma was useful in identifying CRC patients with a poor prognosis. Increased stromal vimentin expression indicated a dynamic change in the tumour stroma during tumour progression. Previous attempts to evaluate the stromal response were based mostly on histological changes of the fibrous tissue in the stroma, including an evaluation of the relative amount of fibrous tissue or the pattern of stroma (Jass et al, 1986; Ueno et al, 2004). Results have been controversial with regard to prognosis. Some suggested a positive correlation, but others have suggested otherwise (Jass et al, 1986; Halvorsen and Seim, 1989; Harrison et al, 1994; Ueno et al, 2004). Nevertheless, these studies indicated that significant histological changes could be observed in the tumour stroma.

A significant part of the change could be attributed to fibroblastic changes, as suggested by other studies, as fibroblasts are the main cell population in tissue stroma. Our data suggest the possibility that stromal fibroblasts may indeed facilitate tumour progression, possibly invasion, and metastasis, leading to a higher rate of disease recurrence. Fibroblasts, being both activated by cytokines and at the same time producing cytokines or other soluble factors, were reported to modulate various aspects of tumour progression including proliferation or invasion (Vogetseder et al, 1989; Nakamura et al, 1997), angiogenesis (Orimo et al, 2001), or inhibition of cell death (Olumi et al, 1998). Vimentin expression is reportedly universally found in all types of fibroblasts (Skalli et al, 1989; Sappino et al, 1990). In comparing the extent of stromal reaction and vimentin expression in this study, however, our data suggest that fibrous tissue itself may not be sufficient to promote tumour progression. Collaboration with other factors in the stroma, including the cellular compartment consisting of lymphocytes and endothelial cells may be necessary to create a microenvironment favourable for tumour progression.

Other histological changes often observed in the tumour stroma are the appearance of lymphocytes. These infiltrating lymphocytes are known as tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL). Vimentin expression is also found in this group of cells. Thus, increased vimentin expression could also indicate increased numbers of TIL. Whether this group of cells protects the host against the tumour cells, or prevents a tumour-specific immune response, remains a controversial topic. A gradual increase in TIL was observed during melanoma tumorigenesis (Hussein et al, 2006). However, increased immune cells in CRC are reportedly associated with better survival (Pages et al, 2005). If indeed the increased vimentin is caused by this group of cells, our results would advocate that TIL suppress the immune response against the tumour. However, we note that recent studies have indicated that different subsets of TIL might have distinct roles in the tumour microenvironment (Yu and Fu, 2006).

As vimentin also stains endothelial cells, increased microvessels in these regions also caused an increase in overall vimentin expression in the stroma. As tumours grow, development of blood vessels becomes necessary to provide needed oxygen and nutrients. In CRC, the correlation between microvessel density and prognosis has been variable, with studies indicating both positive and negative correlations (Neal et al, 2006). In this series, we showed that although the single factor change of microvessel density did not provide any prognostic significance, the overall evaluation with vimentin had useful prognostic value to differentiate between high-risk and low-risk groups.

Furthermore, we found that the prognostic power of vimentin expression was better than that of lymph node metastasis. These data support the notion of vimentin as a novel tumour stromal prognostic marker in CRC. We also found that the prognostic power of vimentin was independent of lymph node status, as well as the stage of histological differentiation. These results support the proposal that stromal therapy may be a viable approach to CRC. Stromal therapy was proposed to be more flexible and applicable to a wider range of disease stages, as its target is dynamic (Liotta and Kohn, 2001). In hepatocarcinoma, chemotherapy was demonstrated to be more effective, if therapies against the underlying fibrosis were also employed (Friedman et al, 2000; Bilimora et al, 2001). It is also of interest that stromal markers, such as vimentin in this study, may be useful in monitoring stromal therapies. Targeting the tumour as an organ would be more effective than targeting the tumour alone.

Here, we provide clinical evidence of stromal response, as evaluated by vimentin expression, as a prognostic indicator for poor prognosis in CRC patients irrespective of lymph node status. Vimentin staining allows an evaluation of overall stromal changes that include fibroblastic changes, microvessel density, infiltrating lymphocytes, and possibly other stromal changes yet to be identified. We note, however, that although the results presented here may be useful as a biological marker, they might not specifically reflect the biological nature of cancer (Nishio et al, 2001). Further assessment of other stromal reaction markers should allow a better understanding of more specific interactions between tumour cells and the microenvironment. A larger scale prospective study will be necessary to verify the prognostic significance of this stromal marker.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Cancer Research from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture Technology, Japan to HY.

References

- Alfonso P, Nunez A, Madoz-Gurpide J, Lombardia L, Sanchez L, Casal JI (2005) Proteomic expression analysis of colorectal cancer by two-dimensional differential gel electrophoresis. Proteomics 5: 2602–2611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altmannsberger M, Weber K, Holscher A, Schauer A, Osborn M (1982) Antibodies to intermediate filaments as diagnostic tools: human gastrointestinal carcinomas express prekeratin. Lab Invest 46(5): 520–526 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andre T, Boni C, Mounedji-Boudiaf L, Navarro M, Tabernero J, Hickish T, Topham C, Zaninelli M, Clingan P, Bridgewater J, Tabah-Fisch I, de Gramont A, Multicenter International Study of Oxaliplatin/5-Fluorouracil/Leucovorin in the Adjuvant Treatment of Colon Cancer (MOSAIC) Investigators (2004) Oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as adjuvant treatment for colon cancer. N Engl J Med 350: 2343–2351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bichat F, Mouawad R, Solis-Recendez G, Khayat D, Bastian G (1997) Cytoskeleton alteration in MCF7R cells, a multidrug resistant human breast cancer cell line. Anticancer Res 17: 3393–3401 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilimora MM, Lauwers GY, Doherty DA, Nagorney DM, Belghiti J, Do K-A, Regimbeau J-M, Ellis LM, Curley SA, Ikai I, Yamaoka Y, Vauthey J-N (2001) Underlying liver disease, not tumour factors, predicts long-term survival after resection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Arch Surg 136: 528–535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bissell MJ, Radisky D (2001) Putting tumours in context. Nat Rev Cancer 1: 46–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brabletz T, Hlubek F, Spadena S, Schmalhofer O, Hiendlmeyer E, Jung A, Kirchner T (2005) Invasion and metastasis in colorectal cancer: epithelial–mesenchymal transition, mesenchymal–epithelial transition, stem cells and β-catenin. Cells Tissues Organs 179: 56–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke EJ, Allan V (2002) Intermediate filaments: vimentin moves in. Curr Biol 12: R596–R598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conforti G, Codegoni AM, Scanziani E, Dolfini E, Dasdia E, Calza M, Caniatti M, Broggini M (1995) Different vimentin expression in two clones derived from a human colocarcinoma cell line (LoVo) showing different sensitivity to doxorubicin. Br J Cancer 71: 505–511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulbecco R, Allen R, Okada S, Bowman M (1983) Functional changes of intermediate filaments in fibroblastic cells revealed by a monoclonal antibody. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 80: 1915–1918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorak HF (1986) Tumors: wound that do not heal. Similarities between tumor stroma generation and wound healing. N Engl J Med 315: 1650–1659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckes B, Colucci-Guyon E, Smola H, Nodder S, Babinet C, Krieg T, Martin P (2000) Impaired wound healing in embryonic and adult mice lacking vimentin. J Cell Sci 113: 2455–2462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson JE, He AV, Trejo-Skalli AV, Harmala-Brasken AS, Hellman J, Chou YH, Goldman RD (2004) Specific in vivo phosphorylation sites determine the assembly dynamics of vimentin intermediate filaments. J Cell Sci 117: 919–932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman SL, Maher JJ, Bissell DM (2000) Mechanisms and therapy of hepatic fibrosis: report of the AASLD single topic basic research conference. Hepatology 32: 1403–1408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halvorsen TB, Seim E (1989) Association between invasiveness, inflammatory reaction, desmoplasia and survival in colorectal cancer. J Clin Pathol 42: 162–166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison JC, Dean PJ, El-Zeky F, Zwaag RV (1994) From Dukes through Jass: pathological prognostic indicators in rectal cancer. Hum Pathol 25: 498–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helfand BT, Chang L, Goldman RD (2004) Intermediate filaments are dynamic and motile elements of cellular architecture. J Cell Sci 117: 133–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann H, Hesse M, Reichenzeller M, Aebi U, Magin TM (2003) Functional complexity of intermediate filament cytoskeletons: from structure to assembly to gene ablation. Int Rev Cytol 223: 83–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussein MR, Elsers DA, Fadel SA, Omar AE (2006) Immunohistological characterisation of tumour infiltrating lymphocytes in melanocytic skin lesions. J Clin Pathol 59: 316–324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jass JR, Atkin WS, Cuzick J, Bussey HJR, Morson BC, Northover JM, Todd IP (1986) The grading of rectal cancer: historical perspectives and a multivariate analysis of 447 cases. Histopathology 10: 437–459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jass JR, Love SB, Northover JMA (1987) A new prognostic classification of rectal cancer. Lancet 1: 1303–1306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang SH, Hyde C, Reid IN, Hitchcock IS, Hart CA, Bryden AAG, Villette J-M, Stower MJ, Maitland NJ (2002) Enhanced expression of vimentin in motile prostate cell lines and in poorly differentiated and metastatic prostate carcinoma. Prostate 52: 253–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liotta LA, Kohn EC (2001) The microenvironment of the tumour–host interface. Nature 411: 375–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellick AS, Day CJ, Weinstein SR, Griffith LR, Morrison NA (2002) Differential gene expression in breast cancer cell lines and stroma-tumour differences in microdissected breast cancer biopsies revealed by display array analysis. Int J Cancer 100: 172–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mor-Vaknin N, Punturieri A, Sitwala K, Markovitz DM (2003) Vimentin is secreted by activated macrophages. Nat Cell Biol 5: 59–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagaraja GM, Othman M, Fox BP, Alsaber R, Pellegrino CM, Zeng Y, Khanna R, Tamburini P, Swaroop A, Kandpal RP (2006) Gene expression signatures and biomarkers of non-invasive and invasive breast cancer cells: comprehensive profiles by representational dfference analysis, microarrays and proteomics. Oncogene 25: 2328–2338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura T, Matsumoto K, Kiritoshi A, Tano Y, Nakamura T (1997) Induction of hepatocyte growth factor in fibroblasts by tumour-derived factors affects invasive growth of tumour cells: in vitro analysis of tumour–stromal interactions. Cancer Res 57: 3305–3313 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neal CP, Garcea G, Doucas H, Manson MM, Sutton CD, Dennison AR, Berry DP (2006) Molecular prognostic markers in respectable colorectal liver metastases: a systematic review. Eur J Cancer 42: 1728–1743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishio K, Inoue A, Qiao S, Kondo H, Mimura A (2001) Senescence and cytoskeleton: overproduction of vimentin induces senescent-like morphology in human fibroblast. Histochem Cell Bio 116: 321–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noura S, Yamamoto H, Ohnishi T, Masuda N, Matsumoto T, Takayama O, Fukunaga H, Miyake Y, Ikenaga M, Ikeda M, Sekimoto M, Matsuura N, Monden M (2002) Comparative detection of lymph node micrometastases of stage II colorectal cancer by reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction and immunohistochemistry. J Clin Oncol 20: 4232–4241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olumi AF, Dazin P, Tlsty TD (1998) A novel coculture technique demonstrates that normal human prostatic fibroblasts contribute to tumour formation of LNCaP cells by retarding cell death. Cancer Res 58: 4524–4530 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orimo A, Tomioka Y, Shimizu Y, Sato M, Oigawa S, Kamata K, Nogi Y, Inoue S, Takahashi M, Hata T, Muramatsu M (2001) Cancer-associated myofibroblasts possess various factors to promote endometrial tumour progression. Clin Cancer Res 7: 3097–3105 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborn M (1983) Intermediate filaments as histology markers: an overview. J Invest Dermatol 81: 104s–107s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pages F, Berger A, Camus M, Sanchez-Cabo F, Costes A, Molidor R, Mlecnik B, Kirilovsky A, Nilsson M, Damotte D, Meatchi T, Bruneval P, Cugnenc PH, Trajanoski Z, Fridman WH, Galon J (2005) Effector memory T cells, early metastasis, and survival in colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 353: 2654–2666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penuelas S, Noe V, Ciudad CJ (2005) Modulation of IMPDH2, surviving, topoisomerase I and vimentin increases sensitivity to methotrexate in HT29 human colon cancer cells. FEBS J 272: 696–710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sappino AP, Schurch W, Gabbiano G (1990) Differentiation repertoire of fibroblastic cells: expression of cytoskeletal proteins as marker of phenotypic modulations. Lab Invest 63: 144–161 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweitzer SC, Evans RM (1998) Vimentin and lipid metabolism. Subcell Biochem 31: 437–462 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S, Sadacharan S, Su S, Belldegrun A, Persad S, Singh G (2003) Overexpression of vimentin: role in the invasive phenotype in an androgen-independent model of prostate cancer. Cancer Res 63: 2306–2311 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skalli O, Schurch W, Seemayer T, Lagace R, Montandon D, Pittet B, Gabbiani G (1989) Myofibroblasts from diverse pathologic settings are heterogenous in their content of actin isoforms and intermediate filament proteins. Lab Invest 60: 275–285 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sordat I, Rousselle P, Chaubert P, Petermann O, Aberdam D, Bosman FT, Sordat B (2000) Tumor cell budding and laminin-5 expression in colorectal carcinoma can be modulated by the tissue micro-environment. Int J Cancer 88: 708–717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueno H, Jones AM, Wilkinson KH, Jass JR, Talbot IC (2004) Histological categorisation of fibrotic cancer stroma in advanced rectal cancer. Gut 53: 581–586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueno H, Murphy J, Jass JR, Mochizuki H, Talbot IC (2002) Tumor ‘budding’ as an index to estimate the potential of aggressiveness in rectal cancer. Histopathology 40: 127–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogetseder W, Feichtinger H, Schulz TF, Schwaeble W, Tabaczewski P, Mitterer M, Bock G, Marth C, Dapunt O, Mikuz G, Dierich MP (1989) Expression of 7F7-antigen, a human adhesion molecule identical to intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) in human carcinomas and their stromal fibroblasts. Int J Cancer 43: 768–773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Bassewitz DB, Roessner A, Grundmann E (1982) Intermediate-sized filaments in cells of normal human colon mucosa, adenomas and carcinomas. Pathol Res Pract 175: 238–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto H, Kondo M, Nakamori S, Nagano H, Wakasa K, Sugita Y, Chang-De J, Kobayashi S, Damdinsuren B, Dono K, Umeshita K, Sekimoto M, Sakon M, Matsuura N, Monden M (2003) JTE-522, a cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor, is an effective chemopreventive agent against rat experimental liver fibrosis. Gastroenterology 125: 556–571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu P, Fu YX (2006) Tumour-infiltrating T lymphocytes: friends or foes? Lab Invest 86: 231–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zajchowski DA, Bartholdi MF, Gong Y, Webster L, Liu H-L, Munishkin A, Beauheim C, Harvey S, Ethier SP, Johnson PH (2001) Identification of gene expression profiles that predicts the aggressive behavior of breast cancer cells. Cancer Res 61: 5168–5178 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]