Abstract

We combined information published worldwide on the seroprevalence of hepatitis B surface antigen (HbsAg) and antibodies against hepatitis C virus (anti-HCV) in 27 881 hepatocellular carcinomas (HCCs) from 90 studies. A predominance of HBsAg was found in HCCs from most Asian, African and Latin American countries, but anti-HCV predominated in Japan, Pakistan, Mongolia and Egypt. Anti-HCV was found more often than HBsAg in Europe and the United States.

Keywords: hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, hepatocellular carcinoma, meta-analysis

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) represents approximately 6% of all new cancer cases diagnosed worldwide, with more than half of these occurring in China alone (Parkin et al, 2005). Relatively high incidence rates are also found in South Eastern Asia and in sub-Saharan Africa (Parkin et al, 2005). One of the least curable malignancies, HCC is the third most frequent cause of cancer death among men worldwide (Parkin et al, 2005).

Chronic infection with hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) are the most important causes of HCC (IARC, 1994). According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), approximately 350 million people are chronically infected with HBV (WHO, 2004) and 170 million with HCV (WHO and the Viral Hepatitis Prevention Board, 1999) worldwide. There are no comparable statistics for the number of individuals coinfected with both HBV and HCV.

The relative importance of HBV and HCV infections in HCC aetiology is known to vary greatly from one part of the world to another (Parkin, 2006), and can change over time (Lu et al, 2006). In order to investigate this issue, we collated all published data on the prevalence of chronic HBV and HCV infection among HCC cases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

MEDLINE and WHO regional indexed databases were used to search for articles published from 1 January 1989 (after HCV testing became available) to 31 October 2006, by means of the MeSH terms: ‘hepatocellular carcinoma’, ‘hepatitis B virus’ and ‘hepatitis C virus or hepacvirus’. Additional relevant studies were identified in the reference lists of selected articles. No language limitation was imposed. Eligible studies had to report prevalence of both hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and antibodies against HCV (anti-HCV), alone and in combination, for at least 20 HCC cases. To avoid multiple inclusions of the same HCC cases in more than one article, the time and place of recruitment of cases were cross-checked and the most recent publication was used. In the event that study methods indicated the availability of HBsAg and anti-HCV prevalence data but did not report both of them and the percent of coinfection in the article, authors were contacted for the supplementary information. In the course of contacting authors, additional data became available from one study expanded since the original publication (Appendix A).

The key information extracted from each study were study country, gender distribution, generation of HCV serology tests used, prevalence of HBsAg alone (HBsAg+) and anti-HCV alone (anti-HCV+) and in combination (HBV/HCV coinfection), and the number of cases that were seronegative for both viral markers.

Key information on 110 selected studies is given in the Appendix A by continent and country. For multicentric studies, HBsAg+ and anti-HCV+ prevalence data were separated by country (Appendix A). Study size varied substantially and four reports (one each from China, Japan, Taiwan and the United States) included more than 1000 HCC cases. With respect to anti-HCV testing, 17 studies (published from 1989 to 1994) reported the use of first-generation enzyme-linked immunoabsorbant assay (ELISA), 29 studies (published from 1992 to 2003) second-generation ELISA and 42 studies (published from 1997 to 2006) third-generation ELISA. Nineteen studies did not report the generation of HCV testing used; four of these were assumed to have used first-generation ELISA based on date of publication or patient admission. Studies known or likely to have used first-generation ELISA were not included in the computation of HCV prevalence owing to known problems of sensitivity and specificity of those assays (Booth et al, 2001). Two studies used HCV RNA instead of anti-HCV, and were included in the analysis (Appendix A).

RESULTS

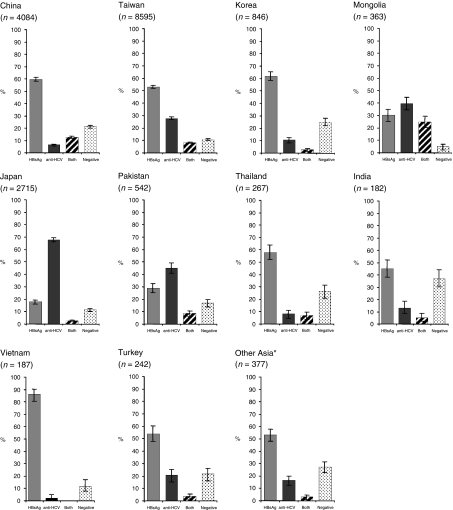

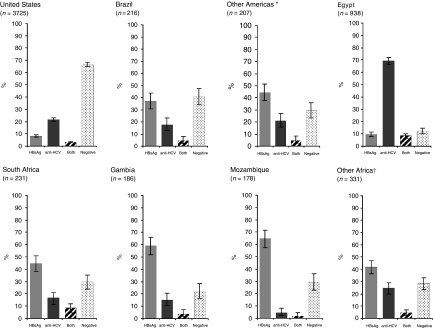

After exclusion of studies using first-generation ELISA for anti-HCV testing, there were 90 studies with relevant data on the prevalence of HBsAg and anti-HCV, covering 27 881 HCC cases from 36 countries (Table 1). The majority of cases were from Asia (66%) followed by the Americas (15%), Europe (12%) and Africa (7%). In Figures 1, 2 and 3, HBsAg+ and anti-HCV+ prevalence data are shown for countries with information on at least 150 HCC cases. Otherwise countries from the same continent were combined. Substantial variations in HBsAg and anti-HCV prevalence were observed between countries and continents.

Table 1. Continent-specific distribution of studies with HCC casesa.

| Continent | No. of studies | HCC cases | Countries represented |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asia | 47 | 18 400 | China, India, Indonesia, Iran, Japan, Korea, Lebanon, Mongolia, Myanmar, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Taiwan, Thailand, Turkey and Vietnam |

| Europe | 22 | 3469 | Austria, Belgium, Germany, Greece, Italy, Sweden, Spain and UK |

| Americas | 12 | 4148 | United States, Brazil, Peru and Mexico |

| Africa | 12 | 1864 | Egypt, Gambia, Mozambique, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, South Africa, Somalia and Sudan |

| Total | 90b | 27 881 |

Studies that used first-generation ELISA for anti-HCV detection were excluded.

Total does not add up to 90 owing to three multi-continent studies.

Figure 1.

Seroprevalence and corresponding 95% confidence intervals of HBsAg, anti-HCV, both and negative in patients with HCC in Asia. *Indonesia, Myanmar, Iran, Lebanon and Saudi Arabia.

Figure 2.

Seroprevalence and corresponding 95% confidence intervals of HBsAg, anti-HCV, both and negative in patients with HCC in Europe. *Belgium and the United Kingdom.

Figure 3.

Seroprevalence and corresponding 95% confidence intervals of HBsAg, anti-HCV, both and negative in patients with HCC in the Americas and Africa. *Peru and Mexico; †Sudan, Nigeria, Niger, Senegal and Somalia.

Asia

The largest number of HCC cases from any single country in Asia came from Taiwan, with 8595 HCC cases identified from a single multicentre study (Lu et al, 2006), Japan and China (Figure 1). The proportion of HBsAg+ HCC cases was greater than 50% in China, Taiwan, Korea, Thailand, Vietnam and Turkey. The lowest proportion of HBsAg+ HCC cases was reported in Japan where there was a strong predominance of anti-HCV seropositivity in HCC cases (68%). A higher proportion of anti-HCV+ than HBsAg+ HCC cases was also found in Pakistan (45%), and in Mongolia (40%), where HBV/HCV coinfection was also very frequent (25%). In China, anti-HCV was found twice as often in combination with HBsAg than alone. The highest proportion of HCC cases seronegative for both hepatitis viruses was found in India (37%).

Europe

The countries in Europe where the largest numbers of HCC cases were studied were Italy, Greece and Germany (Figure 2). The proportion of HBsAg+ HCC cases (56%) was higher than that of anti-HCV+ HCC in Greece, whereas the opposite was observed everywhere else in Europe. In Italy and Spain, the proportions of anti-HCV+ HCC cases were 43 and 48%, respectively. Seropositivity for anti-HCV was significantly higher than for HBsAg also in Austria and Sweden, whereas in Germany the seroprevalence of the two viruses was similar. Hepatitis B virus/HCV coinfection was rare in most European studies, whereas HCC cases seronegative for both hepatitis viruses were relatively common, measuring over 80% in Sweden.

The Americas

A majority of American studies on HCC and hepatitis viruses were conducted in the United States (Figure 3), with two-thirds of HCC cases coming from a nation-wide linkage study for the Surveillance Epidemiology and End-Results Program. In the United States, 9% of HCC cases were HBsAg+ and 22% were anti-HCV+. The prevalence of HBV/HCV coinfection in HCC cases was 3.2% and a high proportion (67%) of HCC cases were seronegative for markers of both hepatitis viruses. In Brazil, 37 and 18% of HCC cases were HBsAg+ and anti-HCV+, respectively. Only 207 additional HCC cases were available from other American countries (Peru and Mexico), where prevalence of HBsAg exceeded that of anti-HCV.

Africa

Nearly half of the data on HCC in Africa came from Egypt (Figure 3), where a very high proportion (69%) of HCC cases was anti-HCV+. All other African countries showed a preponderance of HBsAg seropositivity. HBV/HCV coinfection did not exceed 10% anywhere in Africa, whereas approximately 30% of HCC cases were seronegative for both hepatitis viruses in South Africa and Mozambique.

DISCUSSION

This review, based on nearly 30 000 HCC cases, confirms wide international variation in the relative importance of HBV and HCV in this disease. As expected, HBV infection was found substantially more often than HCV infection in HCC cases from the majority of Asian and African countries with the available data. Conversely, more HCC cases were found to be anti-HCV+ than HBsAg+ in Europe and in the United States, as was also the case in Japan, Pakistan and Mongolia, and in Asia generally. In some countries (i.e., China and Mongolia), more than 10% of HCC cases were coinfected with both hepatitis viruses, thus hampering the attribution of a fraction of HCC cases to HBV or HCV.

More than half of HCC cases were both HBsAg− and anti-HCV− in the United States and some North European countries, thus pointing to the relative importance of heavy alcohol consumption and, possibly, smoking, obesity and diabetes mellitus (Yuan et al, 2004) in areas where hepatitis virus prevalence and HCC incidence are low.

Our systematic review failed to identify information on HBV and HCV infection among HCC cases in Eastern Europe, Russia, Central Asia and the majority of African and Latin American countries. None of the studies we found from Oceania using second- or third-generation ELISA met our inclusion criteria. However, a record-linkage study from New South Wales, Australia showed a similar proportion of HBsAg+ (45%) and anti-HCV+ (53%) HCCs and low frequency of HBV/HCV coinfection (2%) among 281 virus-related HCC cases (Amin et al, 2006).

In addition to lack of data from many parts of the world, some weaknesses of our present review should be borne in mind. The extent to which the HCC cases we reported upon are representative, at a national level, is unclear, especially where only small studies were available. Furthermore, important secular trends may be concealed by our analysis, as in the largest study identified (Lu et al, 2006), which showed a steady increase in the proportion of HCC cases related to HCV in the last two decades in Taiwan. The vast majority of studies did not provide information on occult HBV infection. Occult HBV infection seems, however, to have little or no clinical significance, at least among immunocompetent individuals (Knoll et al, 2006). Most importantly, owing to the long latent period of HCC, seropositivity among HCC cases does not reflect the current importance of the two viruses in the relevant population but rather that two or three decades earlier.

Based upon prevalence of the infections in different populations around the world and a relative risk of 20 for both viruses, Parkin (2006) estimated the fraction of HCC attributable to HBV and HCV in 2002 to be, respectively, 23 and 20% in developed countries and 59 and 33% in developing countries. Our simpler approach, based on HCC cases only, was mainly dictated by the wish to use information from many world populations for whom information on HCC was available but not data on population prevalences of HBV and HCV. It suggests, however, that the relative contribution of HCV to the current HCC burden in middle-aged and old individuals in developed countries and in some developing countries might be higher than in Parkin (2006). In fact, seroprevalence surveys on which attributable risks are based tend to over-sample young individuals at low risk of HCV infection (e.g., blood donors and pregnant women, WHO, 1999; Madhava et al, 2002). In conclusion, our findings underline the importance of the prevention of HCV infection that, in the absence of a vaccine, will require an integrated strategy including screening of blood donations, safe injection practices and avoidance of unnecessary injections (Ahmad, 2004).

Acknowledgments

SA Raza was supported by a Postdoctoral Fellowship from the International Agency for Research on Cancer, where the study was conceived, coordinated and analysed. We thank the authors who provided the additional data from their published studies. Expanded data from Egypt was provided through personal communication from Dr. Christopher Loffredo, Lombardi Cancer Center, Georgetown University School of Medicine, Washington, DC, USA.

Appendix A - See over

Table A1.

|

Cases

|

Prevalence (%)

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First author | Reference | Country | Total | Male | Female | HBsAg+ | Anti-HCV + | HBsAg+ Anti-HCV+ | HBsAg− anti HCV− |

| ASIA | |||||||||

| Shi J | Br J Cancer 2005; 92: 607–612 | China | 3126 | — | — | 59.6 | 7.4 | 14.1 | 18.9 |

| Ding Xc | Jpn J Inf Dis 2003; 56: 19–22 | China | 112 | 98 | 14 | 66.1 | 2.7 | 1.8 | 29.5 |

| Wang BE | J Med Virol 2002; 67: 394–400 | China | 92 | — | — | 67.4 | 4.3 | 6.5 | 21.7 |

| Zhang JY | Int J Epidemiol 1998; 27: 574–578 | China | 152 | 136 | 16 | 55.3 | 3.3 | 7.9 | 33.6 |

| Yu SZ | Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi 1997; 18: 214–216 | China | 340 | — | — | 54.1 | 5.9 | 12.4 | 27.6 |

| Yuan JM | Int J Cancer 1995; 63: 491–493 | China | 76 | 76 | 0 | 64.5 | 0.0 | 1.3 | 34.2 |

| Okuno H | Cancer 1994; 73: 58–62 | China | 186 | 168 | 18 | 65.6 | 0.5 | 4.8 | 29.0 |

| Tao QMa | Gastroenterol Jpn 1991; 26: (Suppl 3) 156–158 | China | 52 | — | — | 38.5 | 9.6 | 28.8 | 23.1 |

| Leung NWa | Cancer 1992; 70: 40–44 | Hong Kong | 424 | 381 | 43 | 76.9 | 3.8 | 3.5 | 15.8 |

| Joshi N | Trop Gastroenterol 2003; 24: 73–75 | India | 40 | 33 | 7 | 47.5 | 20.0 | 0.0 | 32.5 |

| Wang BE | J Med Virol 2002; 7: 394–400 | India | 15 | 11 | 4 | 26.7 | 53.3 | 0.0 | 20.0 |

| Sarin SK | J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2001; 16: 666–673 | India | 74 | 63 | 11 | 63.5 | 4.1 | 8.1 | 24.3 |

| Ramesh R | J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1992; 7: 393–395 | India | 53 | 45 | 8 | 22.6 | 9.4 | 5.7 | 62.3 |

| Wang BE | J Med Virol 2002; 67: 394–400 | Indonesia | 47 | — | — | 21.3 | 40.4 | 2.1 | 36.2 |

| Budihusodo Ua | Gastroenterol Jpn 1991; 26 (Suppl 3): 196–201 | Indonesia | 64 | — | — | 29.7 | 50.0 | 15.6 | 4.7 |

| Hajiani E | Saudi Med J 2005; 26: 974–977 | Iran | 71 | 45 | 26 | 52.1 | 8.5 | 0 | 39.4 |

| Ding Xc | Jpn J Inf Dis 2003; 56: 19–22 | Japan | 122 | 88 | 34 | 27.9 | 59.8 | 9.0 | 3.3 |

| Sharp GB | Int J Cancer 2003; 103: 531–537 | Japan | 159 | — | — | 37.7 | 24.5 | 8.8 | 28.9 |

| Miyazawa K | Intervirology 2003; 46: 150–156 | Japan | 250 | 196 | 54 | 11.6 | 80.4 | 1.2 | 6.8 |

| Wang BE | J Med Virol 2002; 67: 394–400 | Japan | 191 | 140 | 51 | 17.8 | 70.2 | 1.0 | 11.0 |

| Tanioka H | J Infect Chemother 2002; 8: 64–69 | Japan | 1019 | 709 | 310 | 16.4 | 72.6 | 0.9 | 10.1 |

| Fukuhara T | J Radiat Res (Tokyo) 2001; 42: 117–130 | Japan | 168 | — | — | 21.4 | 36.3 | 11.3 | 31.0 |

| Koike Y | Hepatology 2000; 32: 1216–1223 | Japan | 236 | 164 | 72 | 9.7 | 79.7 | 0.4 | 10.2 |

| Abe K | Hepatology 1998; 28: 568–572 | Japan | 122 | 89 | 33 | 18.0 | 61.5 | 4.9 | 15.6 |

| Tanaka K | J Natl Cancer Inst 1996; 88: 742–746 | Japan | 91 | 73 | 18 | 18.7 | 75.8 | 2.2 | 3.3 |

| Shiratori Y | Hepatology 1995; 22: 1027–1033 | Japan | 205 | 163 | 42 | 11.2 | 83.4 | 1.0 | 4.4 |

| Suga M | Hepatogastroenterology 1994; 41: 438–441 | Japan | 63 | 51 | 12 | 27.0 | 54.0 | 9.5 | 9.5 |

| Eto H | Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 1994; 25: 88–92 | Japan | 89 | 69 | 20 | 23.6 | 65.2 | 3.4 | 7.9 |

| Kiyosawa Ka | Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 1992; 31 | Japan | 162 | — | — | 13.0 | 77.8 | 3.1 | 6.2 |

| (Suppl): S150–S156 | 267 | 225 | 42 | 30.7 | 59.6 | 1.5 | 8.2 | ||

| 112 | 94 | 18 | 53.6 | 33.9 | 4.5 | 8.0 | |||

| Yuki Na | Dig Dis Sci 1992; 37: 65–72 | Japan | 148 | 126 | 22 | 17.6 | 61.5 | 8.1 | 12.8 |

| Nishioka Kb | Cancer 1991; 67: 429–433 | Japan | 180 | — | — | 35.6 | 44.4 | 6.1 | 13.9 |

| Saito Ia | Proc Natl Acad Sci 1990; 87: 6547–6549 | Japan | 253 | 207 | 46 | 19.4 | 53.8 | 0.8 | 26.1 |

| Ding Xc | Jpn J Inf Dis 2003; 56: 19–22 | Korea | 55 | 42 | 13 | 69.1 | 5.5 | 3.6 | 21.8 |

| Kwon SY | J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2000; 15: 1282–1286 | Korea | 26 | — | — | 61.5 | 15.4 | 0.0 | 23.1 |

| Abe K | Hepatology 1998; 28: 568–572 | Korea | 55 | 42 | 13 | 81.8 | 5.5 | 3.6 | 9.1 |

| Shin HR | Int J Epidemiol 1996; 25: 933–940 | Korea | 170 | — | — | 65.3 | 10.0 | 1.2 | 23.5 |

| Park BC | J Viral Hepat 1995; 2: 195–202 | Korea | 540 | 431 | 109 | 58.1 | 11.3 | 3.0 | 27.6 |

| Pyong SJa | Jpn J Cancer Res 1994; 85: 674–679 | Korea | 90 | 68 | 22 | 15.6 | 73.3 | 1.1 | 10.0 |

| Yaghi C | World J Gastroenterol 2006; 2: 3575–3580 | Lebanon | 92 | 78 | 14 | 64.1 | 16.3 | 3.3 | 16.3 |

| Tsatsralt-Od Bc | J Med Virol 2005; 77: 491–499 | Mongolia | 76 | 46 | 30 | 17.1 | 14.5 | 68.4 | 0 |

| Shizuma T | Kansenshogaku Zasshi 2005; 79: 824–825 | Mongolia | 90 | — | — | 34.4 | 48.9 | 5.6 | 11.1 |

| Oyunsuren T | Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2006; 7: 460–462 | Mongolia | 197 | 110 | 87 | 30.3 | 39.7 | 25.1 | 5.0 |

| Nakai K | J Clin Microbiol 2001; 39: 1536–1539 | Myanmar | 25 | — | — | 56.0 | 24.0 | 12.0 | 8.0 |

| Hamza H | Proc World Congress of Epidemiology 2005 | Pakistan | 57 | 40 | 17 | 21.1 | 43.9 | 7.0 | 28.1 |

| Khokhar N | J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad 2003; 15: 1–4 | Pakistan | 57 | 45 | 12 | 15.8 | 47.4 | 3.5 | 33.3 |

| Sharieff S | Trop Doct 2001; 31: 224–225 | Pakistan | 201 | 149 | 52 | 35.8 | 41.3 | 7.0 | 15.9 |

| Mumtaz MS | J Rawal Med Coll 2001; 5: 78–80 | Pakistan | 44 | — | — | 25.0 | 54.5 | 6.8 | 13.6 |

| Kausar S | Pak J Gastroenterol 1998; 12: 1–2 | Pakistan | 30 | — | — | 16.7 | 73.3 | 6.7 | 3.3 |

| Butt AK | J Pak Med Assoc 1998; 48: 197–201 | Pakistan | 76 | 65 | 11 | 10.5 | 75.0 | 10.5 | 3.9 |

| Abdul Mujeeb S | Trop Doct 1997; 27: 45–46 | Pakistan | 54 | — | — | 42.6 | 9.3 | 24.1 | 24.1 |

| Tong CY | Epidemiol Infect 1996; 117: 327–332 | Pakistan | 23 | 22 | 1 | 78.3 | 4.3 | 4.3 | 13.0 |

| Ayoola EA | J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004; 19: 665–669 | Saudi Arabia | 118 | 96 | 22 | 63.6 | 8.5 | 3.4 | 24.6 |

| Al Karawi MAa | J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1992; 7: 237–239 | Saudi Arabia | 42 | 38 | 4 | 33.3 | 26.2 | 4.8 | 35.7 |

| Khan LA | Saudi Med J 2001; 22: 641–642 | Saudi Arabia | 24 | 23 | 1 | 20.8 | 25.0 | 4.2 | 50.0 |

| Ozer B | Turk J Gastroenterol 2003; 14: 85–90 | Turkey | 35 | 28 | 7 | 65.7 | 28.6 | 2.9 | 2.9 |

| Uzunalimoglu O | Dig Dis Sci 2001; 46: 1022–1028 | Turkey | 207 | 163 | 44 | 52.2 | 19.3 | 3.9 | 24.6 |

| Lu SN | Int J Cancer 2006; 119: 1946–1952 | Taiwan | 8595 | 6741 | 1854 | 53.2 | 27.9 | 8.3 | 10.7 |

| Tangkijvanich P | J Gastroenterol 1999; 34: 227–233 | Thailand | 86 | 69 | 17 | 58.1 | 10.5 | 8.1 | 23.3 |

| Tangkijvanich P | J Gastroenterol 2003; 38: 142–148 | Thailand | 101 | 86 | 15 | 56.4 | 5.0 | 8.9 | 29.7 |

| Songsivilai S | Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 1996; 90: 505–507 | Thailand | 80 | — | — | 60.0 | 10.0 | 3.8 | 26.2 |

| Ding Xc | Jpn J Inf Dis 2003; 56: 19–22 | Vietnam | 38 | 30 | 8 | 60.5 | 2.6 | 0 | 36.8 |

| Cordier S | Int J Cancer 1993; 55: 196–201 | Vietnam | 149 | 149 | 0 | 92.6 | 2.0 | 0 | 5.4 |

| Continent subtotal | 20194 | 48.1 | 29.2 | 7.9 | 14.8 | ||||

| EUROPE | |||||||||

| Schoniger-Hekele M | Gut 2001; 48: 103–109 | Austria | 245 | 187 | 58 | 9.8 | 36.7 | 1.6 | 51.8 |

| Van Roey G | Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2000; 12: 61–66 | Belgium | 124 | — | — | 21.0 | 23.4 | 16.9 | 38.7 |

| Nalpas Bb | J Hepatol 1991; 12: 70–74 | France | 47 | — | — | 6.4 | 42.6 | 19.1 | 31.9 |

| Erhardt A | Dtsch Med Wochenschr 2002; 127: 2665–2668 | Germany | 192 | — | — | 21.4 | 34.9 | 4.7 | 39.1 |

| Rabe C | World J Gastroenterol 2001; 7: 208–215 | Germany | 85 | 64 | 21 | 29.4 | 24.7 | 7.1 | 38.8 |

| Hellerbrand C | Dig Dis 2001; 19: 345–51 | Germany | 118 | 94 | 24 | 7.6 | 19.5 | 0.0 | 72.9 |

| Kubicka S | Liver 2000; 20: 312–318 | Germany | 268 | 214 | 54 | 25.0 | 16.8 | 10.1 | 48.1 |

| Petry W | Z Gastroenterol 1997; 35: 1059–1067 | Germany | 55 | — | — | 20.0 | 52.7 | 0.0 | 27.3 |

| Goeser T | Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 1994; 3: 311–315 | Germany | 81 | 66 | 15 | 27.2 | 24.7 | 1.2 | 46.9 |

| Raptis I | J Viral Hepat 2003; 10: 450–454 | Greece | 306 | 265 | 41 | 52.3 | 21.9 | 0.7 | 25.2 |

| Kuper HE | Cancer Causes Control 2000; 11: 171–175 | Greece | 333 | 283 | 50 | 59.5 | 12.3 | 3.3 | 24.9 |

| Hadziyannis S | Int J Cancer 1995; 60: 627–631 | Greece | 65 | 49 | 16 | 56.9 | 7.7 | 4.6 | 30.8 |

| Kaklamani Ea | JAMA 1991; 265:1974–1976 | Greece | 185 | 166 | 19 | 22.7 | 15.7 | 23.2 | 38.4 |

| Franceschi S | Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2006; 15: 683–689 | Italy | 229 | 183 | 46 | 10.0 | 61.1 | 3.9 | 24.9 |

| Donato F | Oncogene 2006; 25: 3756–3770 | Italy | 583 | — | — | 19.7 | 37.9 | 2.7 | 39.6 |

| Ricci G | Cancer Lett 1995; 98: 121–125 | Italy | 104 | — | — | 31.7 | 20.2 | 34.6 | 13.5 |

| Stroffolini T | J Hepatol 1992; 16: 360–363 | Italy | 65 | 47 | 18 | 16.9 | 58.5 | 7.7 | 16.9 |

| Simonetti RGa | Ann Intern Med 1992; 116: 97–102 | Italy | 212 | 161 | 51 | 7.1 | 62.7 | 8.5 | 21.7 |

| Levrero Mb | J Hepatol 1991; 12: 60–63 | Italy | 167 | 135 | 32 | 22.8 | 49.1 | 9.0 | 19.2 |

| Colombo Ma | Lancet 1989; 2: 1006–1008 | Italy | 132 | 115 | 17 | 14.4 | 48.5 | 16.7 | 20.5 |

| Ladero JM | Eur J Cancer 2006; 42: 73–77 | Spain | 184 | 150 | 34 | 4.9 | 63.0 | 1.6 | 30.4 |

| Rodriguez Vidigal FF | An Med Interna 2005; 22: 162–166 | Spain | 42 | 37 | 5 | 11.9 | 42.9 | 0.0 | 45.2 |

| Ding Xc | Jpn J Inf Dis 2003; 56: 19–22 | Spain | 57 | 45 | 12 | 38.6 | 12.3 | 3.5 | 45.6 |

| Crespo J | Med Clin (Barc) 1996; 106: 241–245 | Spain | 94 | 82 | 12 | 18.1 | 43.6 | 10.6 | 27.7 |

| Bruix Ja | Lancet 1989; 2: 1004–1006 | Spain | 96 | 67 | 29 | 4.2 | 69.8 | 5.2 | 20.8 |

| Widell A | Scand J Infect Dis 2000; 32: 147–152 | Sweden | 95 | — | — | 5.3 | 16.8 | 0 | 77.9 |

| Kaczynski J | Scand J Gastroenterol 1996; 31: 809–813 | Sweden | 64 | 48 | 16 | 0 | 10.9 | 0 | 89.1 |

| Haydon GH | Gut 1997; 40: 128–132 | United Kingdom | 80 | — | — | 16.3 | 27.5 | 2.5 | 53.8 |

| Continent subtotal | 4308 | 23.1 | 34.3 | 6.5 | 36.1 | ||||

| AFRICA | |||||||||

| Ezzat Sd | Int J Hyg Environ Health 2005; 208: 329–339 | Egypt | 450 | — | — | 3.8 | 82.0 | 5.3 | 8.9 |

| Abdel–Wahab M | Hepatogastroenterology 2000; 47: 663–668 | Egypt | 385 | — | — | 14.5 | 61.0 | 7.0 | 17.4 |

| Hassan MM | J Clin Gastroenterol 2001; 33: 123–126 | Egypt | 33 | 23 | 10 | 12.1 | 72.7 | 3.0 | 12.1 |

| Darwish MA | J Egypt Public Health Assoc 1993; 68: 1–9 | Egypt | 70 | 57 | 13 | 21.4 | 30.0 | 40.0 | 8.6 |

| Kirk GD | Hepatology 2004; 39: 211–219 | Gambia | 186 | — | — | 59.1 | 15.1 | 3.8 | 22.0 |

| Dazza MC | Am J Trop Med Hyg 1993; 48: 237–242 | Mozambique | 178 | 141 | 37 | 64.6 | 4.5 | 1.7 | 29.2 |

| Cenac A | Am J Trop Med Hyg 1995; 52: 293–296 | Niger | 26 | 19 | 7 | 57.7 | 7.7 | 15.4 | 19.2 |

| Olbuyide IO | Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 1997; 91: 38–41 | Nigeria | 64 | 42 | 22 | 48.4 | 7.8 | 10.9 | 32.8 |

| Kew MC | Gastroenterology 1997; 112: 184–187 | South Africa | 231 | 201 | 30 | 44.6 | 16.9 | 8.7 | 29.9 |

| Ka MM | Dakar Med 1996; Spec No: 59–62 | Senegal | 64 | 56 | 8 | 34.4 | 64.1 | 1.6 | 0 |

| Bile K | Scand J Infect Dis 1993; 25: 559–564 | Somalia | 62 | 53 | 9 | 37.1 | 35.5 | 4.8 | 22.6 |

| Omer RE | Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2001; 95: 487–491 | Sudan | 115 | 88 | 27 | 41.7 | 10.4 | 0.9 | 47.0 |

| Continent subtotal | 1864 | 30.0 | 43.2 | 6.8 | 20.0 | ||||

| NORTH AMERICA | |||||||||

| Marrero JA | J Hepatol 2005; 42: 218–224 | United States | 70 | 44 | 26 | 7.1 | 51.4 | 0.0 | 41.4 |

| Davila JA | Gastroenterology 2004; 127: 1372–1380 | United States | 2584 | 1721 | 863 | 5.8 | 13.3 | 2.9 | 77.9 |

| Ding Xc | Jpn J Inf Dis 2003; 56: 19–22 | United States | 65 | 41 | 24 | 15.4 | 41.5 | 3.1 | 40.0 |

| Hassan MM | Hepatology 2002; 36: 1206–1213 | United States | 115 | 87 | 28 | 11.3 | 19.1 | 3.5 | 66.1 |

| Abe K | Hepatology 1998; 28: 568–572 | United States | 65 | 40 | 25 | 10.8 | 41.5 | 1.5 | 46.2 |

| Yu MC | Hepatology 1997; 25: 226–228 | United States | 111 | 67 | 44 | 7.2 | 31.5 | 1.8 | 59.5 |

| Nomura A | J Infect Dis 1996; 173: 1474–1476 | United States | 24 | 24 | 0 | 62.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 37.5 |

| Di Bisceglie | Am J Gastroenterol 2003; 98: 2060–2063 | United States | 691 | — | — | 15.5 | 46.6 | 4.8 | 33.1 |

| Di Biscegliea | Am J Gastroenterol 1991; 86: 335–338 | United States | 99 | 67 | 32 | 6.1 | 12.1 | 1.0 | 80.8 |

| Hasan Fa | Hepatology 1990, 12: 589–591 | United States | 87 | — | — | 27.6 | 35.6 | 4.6 | 32.2 |

| Continent subtotal | 3911 | 8.8 | 21.9 | 3.1 | 66.1 | ||||

| LATIN AMERICA | |||||||||

| Miranda EC | Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 2004; 37 (Suppl 2): 47–51 | Brazil | 36 | 31 | 5 | 58.3 | 0.0 | 8.3 | 33.3 |

| Goncalves CS | Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo 1997; 39: 165–170 | Brazil | 180 | 139 | 41 | 32.8 | 21.1 | 3.9 | 42.2 |

| Mondragon Sanchez R | Hepatogastroenterology 2005; 52: 1159–1162 | Mexico | 71 | — | — | 8.5 | 60.6 | 14.1 | 16.9 |

| Ruiz E | Rev Gastroenterol Peru 1998; 18: 199–212 | Peru | 136 | 116 | 20 | 63.2 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 36.0 |

| Continent subtotal | 423 | 40.7 | 19.4 | 4.7 | 35.2 | ||||

| OCEANA | |||||||||

| Yip Db | World J Gastroenterol 1999; 5: 483–487 | Australia | 63 | 43 | 20 | 28.6 | 3.2 | 4.8 | 63.5 |

| Total | 30763 | 38.3 | 29.7 | 7.0 | 25.0 | ||||

Studies reporting first generation ELISA.

Studies presumed to have used first-generation ELISA.

Studies reporting only HCV RNA testing.

Data has been expanded since original publication.

References

- Ahmad K (2004) Pakistan: a cirrhotic state? Lancet 364: 1843–1844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin J, Dore GJ, O'Connell DL, Bartlett M, Tracey E, Kaldor JM, Law MG (2006) Cancer incidence in people with hepatitis B or C infection: a large community-based linkage study. J Hepatol 45: 197–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth JC, O'Grady J, Neuberger J (2001) Clinical guidelines on the management of hepatitis C. Gut 49(Suppl 1): I1–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IARC (1994) Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans Volume 59: Hepatitis Viruses. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer [Google Scholar]

- Knoll A, Hartmann A, Hamoshi H, Weislmaier K, Jilg W (2006) Serological pattern ‘anti-HBc alone’: characterization of 552 individuals and clinical significance. World J Gastroenterol 12: 1255–1260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu SN, Su WW, Yang SS, Chang TT, Cheng KS, Wu JC, Lin HH, Wu SS, Lee CM, Changchien CS, Chen CJ, Sheu JC, Chen DS, Chen CH (2006) Secular trends and geographic variations of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus-associated hepatocellular carcinoma in Taiwan. Int J Cancer 119: 1946–1952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madhava V, Burgess C, Drucker E (2002) Epidemiology of chronic hepatitis C virus infection in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet Infect Dis 2: 293–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkin DM (2006) The global health burden of infection-associated cancers in the year 2002. Int J Cancer 118: 3030–3044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P (2005) Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin 55: 74–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO and the Viral Hepatitis Prevention Board (1999) Global surveillance and control of hepatitis C. Report of a WHO Consultation organized in collaboration with the Viral Hepatitis Prevention Board, Antwerp, Belgium. J Viral Hepat 6: 35–47 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation (1999) Hepatitis C-global prevalence (update). Wkly Epidemiol Rec 49: 425–427 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation (2004) Hepatitis B vaccines. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 79: 26315344667 [Google Scholar]

- Yuan JM, Govindarajan S, Arakawa K, Yu MC (2004) Synergism of alcohol, diabetes, and viral hepatitis on the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in blacks and whites in the US. Cancer 101: 1009–1017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]