Abstract

This study aimed to identify predictive factors associated with prognostic benefits of gefitinib. A total of 221 Japanese patients who received gefitinib (250 mg day−1) were examined retrospectively and potential predictive factors analysed. Overall response rate (ORR) was 24.4% and median survival time (MST) was 8.0 months. In a log-rank test, survival was significantly better in females, patients with adenocarcinoma, never-smokers, favourable performance status (PS) and patients with epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutation. The lower the smoking exposure (Brinkman Index (BI)=cigarettes per day × years smoked), the better the MST (BI 0: 14.5 months, BI <500: 9.5 months, BI 500 to <1000: 6.9 months, BI ⩾1000: 4.0 months). Positive-EGFR mutation status and PS 0–1 were independent predictors of favourable prognosis by multivariate analysis. Prognosis was significantly different according to EGFR mutation status (with the same smoking status), but not according to smoking status (with the same EGFR mutation status). EGFR mutation status is the most important independent predictor of survival benefit with gefitinib treatment. Although differences in prognosis were observed according to relative smoking status and smoking exposure, the results suggested that smoking is not a direct predictor of prognosis, yet is a surrogate marker of EGFR mutation status.

Keywords: epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitor, EGFR mutations, gefitinib, IRESSA, non-small-cell lung cancer, smoking

Gefitinib (IRESSA) is an orally active small-molecule compound that inhibits the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase (TK) by competing with adenosine triphosphate (ATP) at the ATP-binding site. In two large Phase II trials (IDEAL: IRESSA Dose Evaluation in Advanced Lung cancer 1 and 2) gefitinib-induced tumour regression and provided symptom relief in previously treated patients with non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) (Fukuoka et al, 2003; Kris et al, 2003). Although a placebo-controlled Phase III study (ISEL) in previously-treated patients with NSCLC has not shown a statistically significant improvement in survival associated with gefitinib, preplanned subgroup analysis suggested survival benefits in patients of Asian origin and never-smokers (Thatcher et al, 2005). Patient selection criteria were not incorporated in this comparative study, which most likely contributed to the absence of a positive survival benefit in the overall population. In fact, a Phase II study in which gefitinib was used as first-line therapy for NSCLC in a subgroup of never-smokers with adenocarcinoma reported favourable outcomes, with an overall response rate (ORR) of 61% (Lee et al, 2005).

In 2004, mutations in the EGFR gene conferring increased sensitivity to gefitinib were reported (Lynch et al, 2004; Paez et al, 2004). Recently, very favourable outcomes (response rate (RR) 75%) in a Phase II study of gefitinib as first-line therapy for patients with NSCLC with EGFR gene mutations has been reported (Inoue et al, 2006).

Therefore, it is important to conduct patient selection before using gefitinib and, in particular, it is vital to identify the predictive factors that may contribute to survival. To aid future selection of patient groups for gefitinib treatment we conducted a retrospective analysis of patients who had been treated with gefitinib, assessing the relationship between clinical characteristics, the EGFR mutation status, antitumour activity and patient survival.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

A total of 221 patients who had been initiated on gefitinib monotherapy (250 mg day−1) during a 3-year span from July 2002 (gefitinib was launched in Japan) to June 2005 at the Hyogo Medical Center for Adults in Japan were retrospectively examined.

Clinical assessments

Clinical parameters studied were gender, age, smoking history (Brinkman Index (BI)=number of cigarettes per day × number of years smoked), Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (PS) and previous lines of chemotherapy.

Assessment of tumour regression was conducted according to the response evaluation criteria in solid tumours (RECIST) guideline. The National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria, version 3.0, was used to evaluate toxicity.

EGFR gene analysis

EGFR gene mutation detection was performed on samples from 106 patients: surgical specimens were obtained from 34 patients and a transbronchial lung biopsy (TBLB) was performed on 72 patients. EGFR mutation analysis was successfully performed in 91 of the 106 samples. EGFR mutation was analysed at Aichi Cancer Center Hospital in Japan. A cycleave PCR technique for codon 858 of EGFR gene was used on a SmartCycler system (SC-100, Cepheid, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Deletion in exon 19 of the EGFR gene was detected with fragment analysis using an ABI PRISM 310 genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) (Yatabe et al, 2006). Many of the cases began treatment on gefitinib before it had been reported that EGFR mutation detection was important when treating with the drug. Moreover, many of those cases had already died before our plans to undergo EGFR mutation detection, effectively preventing us from obtaining informed consent in this regard. Accordingly, our Institutional Review Board approved our study plan, provided that samples would be processed anonymously, that samples would be analysed only for somatic mutations and not germline mutations, and that the presence of the study be publicly disclosed, strictly according to the ‘Ethical Guidelines for Human Genome Research’ published by The Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare and The Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, Japan. (http://www.mext.go.jp/a_menu/shinkou/seimei/genome/04122801.htm).

Statistical analysis

OS analysis was conducted on all 221 and 91 patients in which EGFR mutation analysis could be successfully performed.

The differences in responders (complete response; CR+partial response; PR) by each factor (gender, PS, histology, prior chemotherapy, smoking status and mutation status) were examined with the Fisher's exact test. The difference in mutation rate among groups categorised by smoking exposure was examined with χ2 test.

An OS curve was plotted using the Kaplan–Meier method and survival curve comparisons were conducted with the log-rank test. Univariate analysis and multivariate analysis of the impact of the factors, including gender (male vs female), smoking history (ever-smokers vs never-smokers), histology (adenocarcinoma vs others), PS (PS 0–1 vs 2–4) and EGFR mutation (positive vs negative) were conducted using the Cox regression model. All analysis was determined to be statistically significant where the P-value was <0.05.

Analyses were conducted using the SPSS 11.0.1.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

The clinical characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1. The majority of patients (89%) had adenocarcinoma histology. One hundred and thirty-one patients (59%) were ever-smokers.

Table 1. Demographics and relationship between clinical variables and antitumor response/overall survival in patients treated with gefitinib.

| Characteristic | No. of patients (%) | PR (n) | RR (%) | (95% CI) | P-value* | MST (months) | (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 221 | 54 | 24.4 | (18.9–30.6) | 8 | (6.66–9.34) | ||

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 142 (64) | 20 | 14.1 | (8.8–20.9) | <0.001 | 6.8 | (5.04–8.56) | 0.036 |

| Female | 79 (36) | 34 | 43 | (31.9–54.7) | 13.3 | (8.84–17.76) | ||

| Age | ||||||||

| 65< | 100 | 20 | 20 | (12.7–29.2) | 0.208 | 9 | (6.41–11.59) | 0.2852 |

| <65 | 121 | 34 | 28.1 | (20.3–37.0) | 7.3 | (5.88–8.72) | ||

| ECOG PS | ||||||||

| 0–1 | 160 (72) | 44 | 27.5 | (20.7–35.1) | 0.114 | 11.1 | (8.30–13.90) | <0.001 |

| 2–4 | 61 (28) | 10 | 16.4 | (8.2–28.1) | 2.1 | (1.26–2.94) | ||

| Histology | ||||||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 196 (89) | 52 | 26.5 | (20.5–33.3) | 0.048 | 9.3 | (7.66–10.94) | 0.137 |

| Others | 25 (9) | 2 | 8 | (1.0–26.0) | 3.6 | (2.13–5.07) | ||

| Prior chemotherapy | ||||||||

| Yes | 188 (85) | 45 | 24.6 | (18.5–43.3) | 1 | 8.1 | (6.67–9.53) | 1 |

| No | 33 (15) | 9 | 25.7 | (12.5–43.3) | 8.4 | (5.72–11.08) | ||

| Smoking history (n=220) | ||||||||

| No | 89 (40) | 37 | 41.6 | (31.2–52.5) | <0.001 | 14.5 | (10.87–18.13) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 131 (15) | 17 | 13 | (7.7–20.0) | 6.5 | (4.36–8.64) | ||

| BI 1<500 | 25 (11) | 5 | 20 | (6.8–40.7) | 9.5 | (6.41–12.59) | ||

| BI 500 to <1000 | 59 (27) | 9 | 15.3 | (7.2–27.0) | 6.9 | (5.64–8.16) | ||

| BI⩾1000 | 45 (21) | 2 | 4.4 | (0.5–15.1) | 4 | (3.00–5.00) | ||

| EGFR gene status (n=91) | ||||||||

| Wild type | 63 (69) | 7 | 11.1 | (4.6–21.6) | <0.001 | 7.4 | (4.84–9.96) | <0.001 |

| Mutation positive | 28 (31) | 20 | 71.4 | (51.3–86.8) | 24.9 | (14.27–35.53) | ||

| Exon 19 deletion | 19 (21) | 15 | 78.9 | (54.4–93.9) | 16.1 | (6.22–25.98) | ||

| Exon 21 (L858R) | 9 (10) | 5 | 55.6 | (21.2–86.3) | >34.5 | — | ||

| Tumor response (n=191) | ||||||||

| PR | 54 | — | — | 26.2 | (15.76–36.64) | 0.003 | ||

| SD | 59 | — | — | 11.9 | (7.47–16.33) | <0.0001 | ||

| PD | 78 | — | — | 5.6 | (3.20–8.00) | |||

Abbreviations: BI=Brinkman Index; BI=defined as number of cigarettes per day × number of years smoking; CI=confidence interval; EGFR=epidermal growth factor receptor; ECOG PS=Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; MST=median survival time; PD=progressive disease; PR=partial response; RR=response rate; SD=stable disease.*Fisher's exact test.

EGFR mutation analysis and clinical response

TBLB or surgical samples were available from 106 patients for EGFR-mutation detection, but actual analysis was only possible for 103 patients because tumour cells were not found in three post-treatment specimens.

DNA could not be amplified in 12 cases. Analysis of the remaining 91 samples showed EGFR mutations in 28 patients (30.8%) and wild type in 63 patients (69.2%). EGFR mutation rate was high in females, never-smokers and patients with adenocarcinoma. Among ever-smokers, EGFR mutation rate was higher in patients with BI<500 and BI 500 to 1000 than BI >1000 (Table 2). Of the 28 EGFR mutations, 19 (67.9%) were exon 19 in-frame deletions and nine (32.1%) were exon 21-point mutations (L858R). Seven (36.8%) of the exon 19 deletions and four (44.4%) of the L858R cases were smokers. Significantly high mutation rates were observed in females and never-smokers.

Table 2. Mutation rate by patient background.

| Population | N | Mutation (%) | 95%CI | P-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All samples | 91 | 28 (30.8) | ||

| Male | 59 | 12 (20.3) | 11.0–32.8 | 0.005 |

| Female | 32 | 16 (50.0) | 31.9–68.1 | |

| Never-smoker | 38 | 17 (44.7) | 28.6–61.7 | 0.014 |

| Ever-smoker | 53 | 11 (20.8) | 10.8–34.1 | |

| Adeno | 81 | 27 (33.3) | 23.2–44.7 | 0.166 |

| Non-adeno | 10 | 1 (10.0) | 0.3–44.5 | |

| Brinkman Index | ||||

| 0 | 38 | 17 (44.7) | 28.6–61.7 | 0.055b |

| 1≪500 | 9 | 2 (22.2) | 2.8–60.0 | |

| 500≪1000 | 25 | 7 (28.0) | 12.1–49.4 | |

| 1000< | 18 | 2 (11.1) | 1.4–34.7 | |

Fisher's exact test (two-sided).

χ2-test (likelihood ratio).

In the overall population, RR was 24.4% (95% confidence interval (CI) 18.0–30.6%) (Table 1). Response rate was significantly higher among females, patients with adenocarcinoma histology, never-smokers and patients with the EGFR mutation. Disease control rate (DCR: CR+PR+stable disease; SD) was 51.1% (95% CI 44.3–57.9%) and among those with EGFR mutation, 100%.

Survival analyses

Median survival time (MST) in the overall population was 8 months, with 34.8% surviving 1 year. MST among patients showing PR was significantly longer than that in the SD cases (P=0.003) and MST of the SD cases was also shown to be significantly longer than that of the PD cases (P<0.0001) (Table 1).

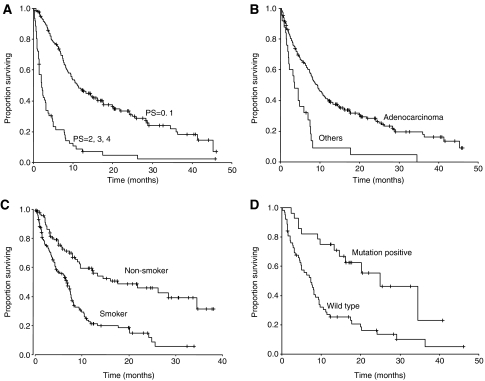

Kaplan–Meier curves indicated significantly longer survival in patients with favourable PS (P<0.0001), in patients with adenocarcinoma histology (P<0.0001), in never-smokers (P<0.0001), and in patients with EGFR mutations (P<0.0001) (Table 1, Figure 1). L858R patients tend to survive longer than those with deletions at exon 19 (P=0.0539). Multivariate analysis was conducted to identify factors contributing to survival. When all patients were analysed considering of the clinical characteristics (gender, adenocarcinoma histology, smoking status and PS), adenocarcinoma, never-smoker status and PS 0–1 were found to be prognostic factors of survival (Table 3a). However, analysis (including that on EGFR mutation status and clinical characteristics) of the patients for whom EGFR mutation results were obtained showed PS 0–1 and EGFR gene mutation status to be the independent prognostic factors, and the relationship between smoking status and survival did not reach statistical significance (Table 3b).

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier plots of survival for patients receiving gefitinib treatment classified according to (A) PS, (B) histology, (C) smoking status and (D) EGFR gene mutation status.

Table 3a. COX Proportional Hazard Model for Survival Analysis in Overall Population (N=221).

| Variable | HR | 95%CI | P–value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Never-smoker/Ever-smoker | 0.413 | 0.294–0.582 | <0.001 |

| Adeno/Non-adeno | 0.416 | 0.265–0.654 | <0.001 |

| PS 0, 1/2–4 | 0.205 | 0.145–0.291 | <0.001 |

Stepwise method (include <0.05, exclude >0.2).

Tested variables; gender, smoking, histology, PS, excluded variable; gender.

Table 3b. COX proportional hazard model for survival analysis in patients in which EGFR mutation status has been detected (n=91).

| Variable | HR | 95%CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adeno/Non-adeno | 0.581 | 0.288–1.171 | 0.129 |

| Never-smoker /ever-smoker | 0.607 | 0.351–1.048 | 0.073 |

| Mutation negative/positive | 2.543 | 1.345–4.808 | 0.004 |

| PS 0, 1/2–4 | 0.166 | 0.091–0.303 | <0.001 |

Tested variables; gender, smoking, histology, PS, mutation excluded variable; gender.

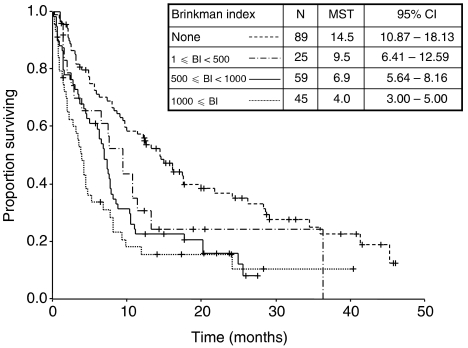

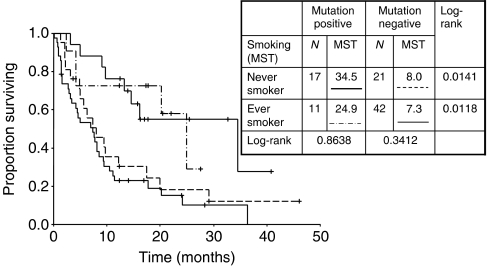

Further analysis of smoking exposure and survival indicated that the higher the exposure, the shorter the MST (Figure 2) . The presence of EGFR mutation was associated with significantly prolonged survival in both never-smokers (P=0.014) and ever-smokers (P=0.012). Furthermore, among EGFR mutation-positive patients, there was no statistically significant difference in median survival between never-smokers and ever-smokers (P=0.864), although patient numbers were small (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Survival stratified by smoking exposure (classified by BI).

Figure 3.

Survival stratified by smoking status and EGFR gene mutation status.

Tolerability

Adverse events were observed in 165 out of 221 (75%) patients. Common adverse events were rash/dry skin (51%), diarrhoea (22%), liver dysfunctions (20% (2.3% were Grade 3)) and paronychia (14%). Sixteen (7%) of the patients developed interstitial lung disease (ILD) and three (1.4%) died. As three out of 14 (21%) patients with PS 3 developed ILD, patients with poorer PS were more likely to develop ILD. There were no differences in ILD incidence by gender, smoking history, age or histology. ILD was experienced by four out of 63 patients with wild type and two out of 28 patients with EGFR mutation (both with an exon 19 deletion).

DISCUSSION

The data from this retrospective study suggest that in a practical setting

A favourable PS, adenocarcinoma histology, never-smoking and presence of an EGFR mutation are predictive of increased antitumour activity with gefitinib,

Although PR cases showed longer median survival than SD cases, SD cases also displayed significantly longer median survival than PD cases,

Although, in terms of clinical characteristics, PS 0–1, adenocarcinoma histology and never-smoking status are predictive factors of survival with gefitinib in the overall population, PS 0–1 and EGFR mutation status were identified as independent predictive factors in patients in which EGFR mutation status has been detected,

The relationships between smoking/EGFR mutation status and survival suggest that the latter is more related to prognosis. Conceivably, smoking has a strong confounding relationship with EGFR mutation status and smoking exposure can result in a different prognosis.

IDEAL 1 reported favourable antitumour activity in females and patients with adenocarcinoma histology (Fukuoka et al, 2003). Several subsequent retrospective studies have reported that female gender, adenocarcinoma histology, bronchioloalveolar subtype, never-smokers and patients with favourable PS are predictive factors of response (Miller et al, 2004; Kim et al, 2005; Lim et al, 2005; Ando et al, 2006). EGFR mutation has been reported as a predictor of efficacy of gefitinib and erlotinib (Lynch et al, 2004; Pao et al, 2004). There have been several reports of clinical factors associated with EGFR mutations, and per the univariate analysis, mutation frequency is high in patients of East Asian ethnicity, females, never-smokers and adenocarcinomas (Kosaka et al, 2004; Paez et al, 2004; Shigematsu et al, 2005; Tokumo et al, 2005). Moreover, multivariate analysis has shown that adenocarcinoma histology and never-smoker status are independent factors associated with EGFR mutation (Kosaka et al, 2004; Tokumo et al, 2005). Reports to date have shown that approximately 90% of EGFR mutations are centred around the L858R point mutation in exon 21 and deletions centred around codons 746–750 in exon 19 (Kosaka et al, 2004; Shigematsu et al, 2005; Sonobe et al, 2005; Tokumo et al, 2005). As association between these two types of EGFR mutations and the antitumour activity and prolonged survival with gefitinib has been reported (Han et al, 2005; Mitsudomi et al, 2005), we conducted analysis on these two types of mutations only. Our results were compatible with those from prospective Phase II studies conducted in patients with EGFR mutation (Inoue et al, 2006; Okamoto et al, 2006). Epidermal growth factor receptor mutation therefore appears to be a more specific criterion for gefitinib use than patient selection according to clinical characteristics.

The relatively high incidence of ILD (3.5–5.8%) in patients treated with gefitinib has been reported in Japan. It also revealed that male gender, ever-smokers, poor PS and the coincidence of interstitial pneumonia were predictive factors for the development of ILD (Yoshida, 2005; Ando et al, 2006). Although these predictive factors contrast with those for the presence of an EGFR mutation, two of the 28 patients with an EGFR mutation developed ILD in our study.

In our examination of prognostic factors, we analysed the relationship particularly between smoking status (ever-/never-smoker, smoking exposure) and two types of EGFR mutations, as well as the relationship between smoking status and EGFR mutation. Our findings indicated that patients with EGFR mutation had significantly longer MST in both ever- and never-smokers, and there was no significant difference in MST between ever- and never-smokers with the same mutation status. This led to the conclusion that the essential factor associated with survival is EGFR mutation status. Though better MST has been reported in L858R cases in a comparison of survival between exon 19 deletion and L858R missense (Shigematsu et al, 2005), recent reports have shown better survival in patients with exon 19 deletion (Jackman et al, 2006; Riely et al, 2006). Incidentally, we found MST to be better in L858R cases. As reported by Jackman et al (2006), RR was more favourable among the exon 19 deletion cases. Although this was conceivably due to factors including the ILD being experienced in two cases with exon 19 deletion and the impact of post-gefitinib treatment, the relatively small sample did not allow for any clarification in this respect.

Our data also show that the larger the smoking exposure, the shorter the survival.

There have been several reports of an inverse correlation between smoking exposure and EGFR mutation rate (Han et al, 2005; Pham et al, 2006; Sugio et al, 2006; Tam et al, 2006; Toyooka et al, 2006). In line with these studies, our data show that smoking status, unlike EGFR mutation status, is not an independent prognostic factor. Considered in combination with past reports on smoking exposure and EGFR mutation rates, the inverse correlation between smoking exposure and MST shown by our data might conceivably reflect that mutation rates differ according to smoking exposure. They also indicate that smoking status is a very powerful surrogate marker of EGFR mutation status, which is a prognostic factor for prolonged survival with gefitinib treatment. Our multivariate analysis in terms of clinical characteristics indicates that smoking status is a significant predictor. However, the multivariate analysis adding EGFR mutation status eliminates the significant difference with regard to smoking, demonstrating that EGFR mutation status and PS 0–1 are independent prognostic factors. This also suggests that ECOG PS and EGFR mutation status are factors that can be used to predict the intrinsic effect of gefitinib on patients as well as their prognosis, supporting the claim that smoking could be a surrogate marker of EGFR mutation status for prediction of survival benefit. Although RR in never-smokers and cases with EGFR mutation on erlotinib, which is also an EGFR-TKI, has been significantly favourable, there has only been marginal significant interaction between survival and smoking status (Clark et al, 2006). However, no significant differences have been reported in regard to EGFR mutation status, and detection of the EGFR mutation is considered unnecessary in treatment using erlotinib (Tsao et al, 2005; Clark et al, 2006). Our results showing that EGFR mutation and smoking status can function as predictors of survival benefit differ from reports on erlotinib. However, they concur with reports to date on gefitinib, presumably suggesting the necessity to select patients before using gefitinib. Further clinical studies are warranted to examine the survival benefits of gefitinib according to EGFR mutation status, that is, to make the EGFR mutation status an inclusion criterion. Considerations should be made in clinical practise to analyse actively EGFR mutations status where possible. However, it is often very difficult to obtain histological specimens of advanced and recurrent lung cancer for which gefitinib is indicated. In fact, in this study we were only able to obtain analytical results for EGFR mutation status for 91 out of 221 (42%) patients. Another problem is EGFR mutation analysis takes time, about 1–3 weeks, necessitating a wait-time before treatment. Therefore, when a certain clinical environment does not allow for, or complicates the detection of EGFR mutations, smoking exposure/smoking status could be a quick and inexpensive reference as a surrogate marker of EGFR mutation status. In future, it will be necessary to evaluate the survival benefits of gefitinib via a Phase III study in patients with these better predictive factors.

IRESSA is a trademark of the AstraZeneca group of companies.

References

- Ando M, Okamoto I, Yamamoto N, Takeda K, Tamura K, Seto T, Ariyoshi Y, Fukuoka M (2006) Predictive factors for interstitial lung disease, antitumor response, and survival in non-small-cell lung cancer patients with gefitinib. J Clin Oncol 24: 2549–2556, doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.04.9866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark GM, Zborowski DM, Santabarbara P, Ding K, Whitehead M, Seymour L, Shepherd FA (2006) Smoking history and epidermal growth factor receptor expression as predictors of survival benefit from erlotinib for patients with non-small-cell lung cancer in the National Cancer Institute of Canada clinical trials group study BR.21. Clin Lung Cancer 7: 389–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuoka M, Yano S, Giaccone G, Tamura T, Nakagawa K, Douillard JY, Nishiwaki Y, Vansteenkiste J, Kudoh S, Rischin D, Eek R, Harai T, Noda K, Takata I, Smit E, Averbuch S, Macleod A, Feyereislova A, Dong RP, Baselga J (2003) Multi-institutional randomized phase II trial of gefitinib for previously treated patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (The IDEAL 1 trial). J Clin Oncol 21: 2237–2246, doi:10.1200/JCO.2003.10.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han S, Kim T, Hwang PG, Jeong S, Kim J, Choi IS, Oh D-Y, Kim JH, Kim D-W, Chung DH, Im S-A, Kim YT, Lee JS, Heo DS, Bang Y-J, Kim NK (2005) Predictive and prognostic impact of epidermal growth factor receptor mutation in non-small-cell lung cancer patients treated with gefitinib. J Clin Oncol 23: 2493–2501, doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.01.388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue A, Suzuki T, Fukuhara T, Maemondo M, Kimura Y, Morikawa N, Watanabe H, Saijo Y, Nukiwa T (2006) Prospective phase II study of gefitinib for chemotherapy-naïve patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer with epidermal growth factor receptor gene mutations. J Clin Oncol 24: 3340–3346, doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.05.4692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackman DM, Yeap B, Sequist LV, Lindeman N, Holmes AJ, Joshi VA, Bell DW, Huberman MS, Halmos B, Rabin MS, Haber DA, Lynch TJ, Mayerson M, Johnson BE, Jänne PA (2006) Exon 19 deletion mutation of epidermal growth factor receptor are associated with prolonged survival in non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with gefitinib or erlotinib. Clin Cancer Res 12: 3908–3914, doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K-S, Jeong J-Y, Kim Y-C, Na K-J, Kim Y-H, Ahn S-J, Baek S-M, Park C-S, Park C-M, Kim Y-I, Lim S-C, Park K-O (2005) Predictors of the response to gefitinib in refractory non-small-cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res 11: 2244–2251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosaka T, Yatabe Y, Endoh H, Kuwano H, Takahashi T, Mitsudomi T (2004) Mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor gene in lung cancer: biological and clinical implications. Cancer Res 64: 8919–8923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kris MG, Natale RB, Herbst RS, Lynch TJ, Prager D, Belani CP, Schiller JH, Kelly K, Spiridonidis H, Sandler A, Albain KS, Cella D, Wolf MK, Averbuch SD, Ochs JJ, Kay AC (2003) Efficacy and safety of gefitinib (ZD1839, Iressa™), an inhibitor of the epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase, in symptomatic patients with non-small cell lung cancer: a randomized trial. JAMA 290: 2149–2158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DH, Han JY, Lee HG, Lee JJ, Lee EK, Kim HY, Hong EK, Lee JS (2005) A Phase II study of gefitinib (ZD1839; Iressa) as a first-line therapy for never-smoker with adenocarcinoma or metastatic adenocarcinoma of the lung. J Clin Oncol 23: 638s (suppl; abstr 7072) [Google Scholar]

- Lim S-T, Wong E-H, Chuah K-L, Leong S-S, Lim W-T, Tay M-H, Toh C-K, Tan E-H (2005) Gefitinib is more effective in never-smokers with non-small-cell lung cancer: experience among Asian patients. Br J Cancer 93: 23–28, doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6602652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch TJ, Bell DW, Sordella R, Gurubhagavatula S, Okimoto RA, Brannigan BW, Harris PL, Haserlat SM, Supko JG, Haruska FG, Louis AN, Christiani DC, Settleman J, Haber DA (2004) Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med 350: 2129–2139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller VA, Kris MG, Shah N, Patel J, Azzoli C, Gomez J, Kruz LM, Pao W, Rizvi N, Pizzo B, Tyson L, Venkatraman E, Ben-Porat L, Memoli N, Zakowski M, Rusch V, Heelan RT (2004) Bronchioloalveolar pathologic subtypes and smoking history predict sensitivity to gefitinib in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 22: 1103–1109, doi:10.1200/JCO.2004.08.158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsudomi T, Kosaka T, Endoh H, Horio Y, Hida T, Mori S, Hatooka S, Shinoda M, Takahashi T, Yatabe Y (2005) Mutations of epidermal growth factor receptor gene predict prolonged survival after gefitinib treatment in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer with postoperative recurrence. J Clin Oncol 23: 2513–2520, doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.00.992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto I, Kashii T, Urata Y, Hirashima T, Kudoh S, Ichinose Y, Ebi N, Satoh T, Tamura K, Fukuoka M (2006) EGFR mutation-based phase II multicenter trial of gefitinib in advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients (pts): Results of West Japan Thoracic Oncology Group trial (WJTOG0403). J Clin Oncol 24: 18s (suppl; abstr 7073) [Google Scholar]

- Paez JG, Jänne PA, Lee JC, Tracy S, Greulich H, Gabriel S, Herman P, Kaye FJ, Lindeman N, Boggan T, Naoki K, Sasaki H, Fujii Y, Eck MJ, Sellers WR, Johnson BE, Meyerson M (2004) EGFR mutation in lung cancer: correlation with clinical response to gefitinib therapy. Science 304: 1497–1500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pao W, Miller V, Zakowski M, Doherty J, Polti K, Sarkaria I, Singh B, Heelan R, Rusch V, Fulton L, Mardis E, Kupfer D, Wilson R, Kris M, Varmus H (2004) EGF receptor gene mutations are common in lung cancer from ‘never smokers’ and are associated with sensitivity of tumors to gefitinib and erlotinib. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 13306–13311, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405220101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham DP, Kris MG, Riely GJ, Sarkaria IS, McDonough T, Chuai S, Venkatraman ES, Miller VA, Ladanyi M, Pao W, Wilson RK, Singh B, Rusch VW (2006) Use of cigarette-smoking history to estimate the likelihood of mutations in epidermal growth factor receptor gene exons 19 and 21 in lung adenocarcinomas. J Clin Oncol 24: 1700–1704, doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.04.3224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riely GJ, Pao W, Pham D, Li AR, Rizvi N, Venkatraman ES, Zakowski MF, Kris MG, Ladanyi M, Miller VA (2006) Clinical course of patients with non-small cell lung cancer and epidermal growth factor receptor exon 19 and exon 21 mutations treated with gefitinib or erlotinib. Clin Cancer Res 12: 839–844, doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shigematsu H, Lin L, Takahashi T, Nomura M, Suzuki M, Wistuba II, Fong KM, Lee H, Toyooka S, Shimizu N, Fujisawa T, Feng Z, Roth JA, Herz J, Minna JD, Bazdar AF (2005) Clinical and biological features associated with epidermal growth factor receptor gene mutation in lung cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst 97: 339–346, doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonobe M, Manabe T, Wada H, Tanaka F (2005) Mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor gene are linked to smoking-independent, lung adenocarcinoma. Br J Cancer 93: 355–363, doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6602707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugio K, Uramoto H, Ono K, Oyama T, Hanagiri T, Sugaya M, Ichiki Y, So T, Nakata S, Morita M, Yasuoto K (2006) Mutations within the tyrosine kinase domain of EGFR gene specifically occur in lung adenocarcinoma patients with a low exposure of tobacco smoking. Br J Cancer 94: 896–903, doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6603040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tam IY, Chung LP, Suen WS, Wang E, Wong MC, Ho KK, Lam WK, Chiu SW, Girad L, Minna JD, Gazdar AF, Wong MP (2006) Distinct epidermal growth factor receptor and KRAS mutation patterns in non-small cell lung cancer patients with different tobacco exposure and clinicopathologic features. Clin Cancer Res 12: 1647–1653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thatcher N, Chang A, Parikh P, Pereira JR, Ciuleanu T, Pawel J, Thongprasert S, Tan EH, Pemberton K, Archer V, Carrol K (2005) Gefitinib plus best supportive care in previously treated patients with refractory advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: results from a randomized, placebo-controlled, multicentre study (Iressa Survival Evaluation in Lung Cancer). Lancet 36: 1527–1537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokumo M, Toyooka S, Kiura K, Shigematsu H, Tomii K, Aoe M, Ichimura K, Tsuda T, Yano M, Tsukuda K, Tabata M, Ueoka H, Tanimoto M, Date H, Gazder AF, Shimizu N (2005) The relationship between epidermal growth factor receptor mutations and clinicopathologic features in non-small cell lung cancers. Clin Cancer Res 11: 1167–1173 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyooka S, Tokumo M, Shigenatsu H, Matsuo K, Asano H, Tomii K, Ichihara S, Suzuki M, Aoe M, Date H, Gazdar AF, Shimizu N (2006) Mutational and epigenetic evidence for independent pathways for lung adenocarcinomas arising in smokers and never smokers. Cancer Res 66: 1371–1375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsao MS, Sakurada A, Cutz JC, Zhu CQ, Kamel-Reid S, Squire J, Lorimer I, Zhang T, Liu N, Daneshmand M, Marrano P, Santos GC, Lagarde A, Richardson F, Seymour L, Whitehead M, Ding K, Pater J, Shepherd FA (2005) Erlotinib in lung cancer-molecular and clinical predictors of outcome. N Engl J Med 353: 133–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yatabe Y, Hida T, Horio Y, Kosaka T, Takahashi T, Mitsudomi T (2006) A rapid, sensitive assay to detect EGFR mutation in small biopsy specimens from lung cancer. J Mol Diagn 8: 335–341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida S (2005) The results of gefitinib prospective investigation. Med Drug J 41: 772–789 [Google Scholar]