Abstract

Previous studies indicated that the central nervous system induces release of the cardiac hormone atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) by release of oxytocin from the neurohypophysis. The presence of specific transcripts for the oxytocin receptor was demonstrated in all chambers of the heart by amplification of cDNA by the PCR using specific oligonucleotide primers. Oxytocin receptor mRNA content in the heart is 10 times lower than in the uterus of female rats. Oxytocin receptor transcripts were demonstrated by in situ hybridization in atrial and ventricular sections and confirmed by competitive binding assay using frozen heart sections. Perfusion of female rat hearts for 25 min with Krebs–Henseleit buffer resulted in nearly constant release of ANP. Addition of oxytocin (10−6 M) significantly stimulated ANP release, and an oxytocin receptor antagonist (10−7 and 10−6 M) caused dose-related inhibition of oxytocin-induced ANP release and in the last few minutes of perfusion decreased ANP release below that in control hearts, suggesting that intracardiac oxytocin stimulates ANP release. In contrast, brain natriuretic peptide release was unaltered by oxytocin. During perfusion, heart rate decreased gradually and it was further decreased significantly by oxytocin (10−6 M). This decrease was totally reversed by the oxytocin antagonist (10−6 M) indicating that oxytocin released ANP that directly slowed the heart, probably by release of cyclic GMP. The results indicate that oxytocin receptors mediate the action of oxytocin to release ANP, which slows the heart and reduces its force of contraction to produce a rapid reduction in circulating blood volume.

There is considerable evidence that the central nervous system is critically involved in release of the cardiac hormone atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) in response to volume expansion (1–4). For example, lesions in the median eminence or neural lobe of the pituitary gland which interrupt neuronal projections to the neurohypophysis, thereby blocking the release of neurohypophyseal hormones, block volume expansion-induced ANP release (5). The two major neurohypophyseal hormones are vasopressin and oxytocin, both of which are important to control hydromineral homeostasis (6, 7). Sonnenberg and Veress (8) showed that vasopressin enhances ANP release from isolated atria. These in vitro studies have not been confirmed, but later experiments showed that vasopressin-stimulated ANP release is related to hemodynamic changes, as only pressor doses of vasopressin produced an immediate increase in plasma ANP (9).

Oxytocin is involved in reproductive functions such as induction of myometrial contractions during parturition and milk ejection during lactation. The presence of similar numbers of magnocellular oxytocin-secreting neurons (10), and the similar plasma oxytocin concentrations in rats of both sexes suggest that oxytocin also subserves other important physiologic functions. Indeed, there is substantiated evidence that oxytocin is important in ingestive (11), sexual (12), maternal (13), and social stress-related behaviors, and in the processing of cognitive information (14) as well as in the regulation of water and salt homeostasis (15, 16).

We have recently shown that (i) volume expansion produced by isotonic or hypertonic saline caused a rapid increase in plasma oxytocin concentrations, paralleled by a concomitant increase of plasma ANP; (ii) intravenous injection of oxytocin induced a dose-related increase in plasma ANP levels; and (iii) intraperitoneal injection of oxytocin in water-loaded rats produced significant natriuresis, kaliuresis, increased urinary osmolality accompanied by an increase in plasma ANP (17). Therefore, we hypothesized that oxytocin released by volume expansion stimulated putative oxytocin receptors in the heart to stimulate the release of ANP that in turn acts on the kidney to induce natriuresis.

ANP also has a vasorelaxant action that would rapidly reduce circulating blood volume. It occurred to us that ANP might have physiologically significant negative chronotropic and inotropic effects on the atria to reduce cardiac output that would further reduce circulating blood volume. Because oxytocin releases ANP, we hypothesized that it would have a negative chronotropic and inotropic effect mediated by ANP. Indeed, oxytocin had a negative chronotropic and inotropic action on rat atria in vitro which was mimicked by a 10-fold lower dose of ANP (18). Oxytocin also evoked the release of ANP from quartered atrial slices; this release was blocked by an oxytocin antagonist (18).

These data suggest that oxytocin may be a physiologically relevant stimulus of ANP release (19). The biological actions of oxytocin are mediated by specific receptors (20); however, there is no prior evidence of oxytocin receptors in the heart. The oxytocin receptor gene is expressed in various tissues of the reproductive tract that are considered as target sites for oxytocin actions (21–24). Oxytocin receptors have been found in other peripheral tissues, such as the kidney (25), mammary and pituitary glands (22), and in several brain regions (26–28). The rat oxytocin receptor gene has been cloned and characterized, and the availability of specific rat oxytocin receptor cDNA probes (29) prompted us to study the heart as a site of oxytocin receptor gene expression. Therefore, the objective of the present study was to characterize at the molecular level the oxytocin receptors in the chambers of the rat heart and to demonstrate their functionality.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Adult Sprague–Dawley female rats (200–250 g) used for this study were obtained from Charles River Laboratories. They were housed four per cage in a temperature-controlled room (22°C) with constant light/dark cycle (lights on 6:00–18:00 h). Laboratory Chow (Ralston Purina) and tap water were given ad libitum. Rats were killed in the morning. Tissues were collected in liquid nitrogen for membrane binding or molecular studies or in isopentane in dry ice for autoradiography and in situ hybridization.

Reverse Transcription–PCR (RT-PCR) Analysis.

The RT-PCR assay used in this study has been described by Breton et al. (30). Briefly, total RNA from dissected heart compartments and control uterus tissue of Sprague–Dawley adult female rats was extracted using the acid guanidinum/thiocyanate/phenol/chloroform method. The integrity of the preparations was verified by gel electrophoresis and RNA concentrations were measured by UV spectrophotometry. RT was performed under standard conditions using random primers and murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). The primer pair used for PCR amplification was separated on the rat oxytocin receptor gene by a large (over 12 kb) intron, hence preventing amplification of any contaminating genomic DNA. The sequence of the forward primer (5′-GTCAATGCGCCCAAGGAAG-3′) corresponded to bases 2821–2840 of the oxytocin receptor gene (numbering according to ref. 28). The reverse primer (bases 3927–3946, 5′-GATGCAAACCAATAGACACC-3′) was complementary to a segment in the 3′ untranslated region. The cycle parameters for PCR were 1.5 min at 94°C, 1.5 min at 94°C, and 2 min at 72°C. Control RT-PCRs were performed by omitting reverse transcriptase or RNA from the reaction mixture. For quantitation of the PCR, 10 μCi [32P]dCTP (1 Ci = 37 GBq) was added to the PCR buffer. The PCR products were electrophoresed in 2% agarose and transferred to a nylon membrane (Hybond N, Amersham). Radioactive bands were counted using a PhosphorImager and Image-Quant (Molecular Dynamics) software. A similar procedure was applied for amplification of rat glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) mRNA as described (30). The predicted size of the cDNA amplification product was 470 bp.

In Situ Hybridization.

Oxytocin receptor mRNA was detected in heart sections with a synthetic oligonucleotide probe according to the protocol described by Wisden and Morris (31). Frozen, dissected hearts were mounted on cryostat chucks, and 10-μm-thick sections were prepared. The sections were thaw-mounted on precleaned, poly-l-lysine-coated slides, fixed for 5 min in ice-cold 4% paraformaldehyde, then washed both for 5 min in PBS and 70% ethanol and stored in 95% ethanol at 4°C in a cold room until required. The oligonucleotide probe (0.3 pmol) was labeled by terminal transferase (Life Technologies) with [α-32P]dCTP of 2500 Ci/mM (Amersham) using a 30:1 molar ratio of isotope to oligonucleotide. The oligonucleotide probe was purified on a Sephadex G-25 spin column. The probes of activity between 100,000 and 200,000 dpm μl−1 32P were diluted to 0.3 pmol/5,000 μl in hybridization buffer containing 50% formamide, 4× standard saline citrate (SSC), and 10% dextran sulfate. After overnight hybridization at 37°C, the slides were washed 10 min with 1× SSC at room temperature, 30 min into prewarmed 1× SSC at 60°C, then sequentially rinsed in 1× SSC, 0.1× SSC, 70% ethanol, and 95% ethanol. The dried tissue sections were placed in a phosphor-sensitive cassette for 72 h, after which the images were scanned, visualized, and quantified using a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics). The controls included hybridization in the presence of 100-fold excess of unlabeled probe and hybridization with a labeled sense oligonucleotide that corresponded to bases 2821–2840 of the oxytocin receptor gene.

Binding Studies.

Heart tissues were homogenized using a Polytron (setting 6, twice for 10 sec each time) in 0.2 M sucrose solution containing 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF: P-766; Sigma). The tissue homogenates were centrifuged at 600 × g for 10 min at 4°C; then the supernatant was saved and the pellet was rehomogenized and centrifuged as above. Both supernatants were combined and centrifuged at 30,000 × g for 40 min at 4°C. The pellet, corresponding to the crude membrane fraction was resuspended in 0.5 ml TM solution (50 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.4/10 mM MgCl2) and stored at −80°C. The protein concentration was determined on an aliquot by the Bradford method (32). Iodinated [d(CH2)5Tyr(OMe)2,Thr4,Tyr9-NH2]OVT (No. 8120, Peninsula Laboratories), a highly specific oxytocin antagonist was used as a ligand for binding experiments. Optimal conditions (protein concentration and incubation time) of oxytocin antagonist to heart membranes were determined in initial experiments. Consequently, the reaction mixture (250 μl) consisted of iodinated tracer (20,000–600,000 cpm) and crude membranes (200 μg protein) in TM. Nonspecific binding was determined in the presence of 10−6 M oxytocin. Homologous competition experiments were performed by adding increasing concentrations of cold ligand (10−12–10−7 M) to the reactions. Reactions were performed in duplicate at room temperature for 1 h and stopped by addition of 3 ml ice-cold TM and followed by rapid filtration through Whatman GF/C filters presoaked in 1% polyethylenimine (P-3143; Sigma). The filters were washed twice with 3 ml cold 50 mM Tris⋅HCl buffer (pH 7.4) and then dried. Receptor bound radioactivity was measured in a γ-counter (Cobra II Auto-gamma; Canberra-Packard, Canada). Scatchard analysis was performed using Ligand computer-based program (Elsevier-Biosoft, Cambridge, U.K.).

Autoradiography.

The frozen, dissected heart compartments were mounted on cryostat chucks, and 20-μm-thick sections were prepared. The sections were thaw-mounted on precleaned, gelatin-coated slides and stored at −80°C until used. For autoradiography, the heart sections were preincubated for 15 min at room temperature in 50 mM Tris⋅HCl buffer (pH 7.4) containing 0.1% polyethylenimine to reduce nonspecific binding. The sections were then incubated at room temperature for 60 min with either iodinated oxytocin antagonist [d(CH2)5Tyr(OMe)2,Thr4,Tyr9-NH2]OVT alone or with increasing concentrations (10−10–10−6 M) of unlabeled oxytocin (no. 8152; Peninsula Laboratories) or oxytocin antagonist. The incubation buffer contained 50 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.4) with 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 40 μg/ml Bacitracin (no. B-0125; Sigma), and 0.5% BSA. At the end of the incubation period, the slides were washed twice (2 min each) with incubation buffer, once with Tris⋅HCl buffer (pH 7.4) at 4°C. This was followed by a wash in distilled water. Then the sections were dried under a stream of cold air. The dried tissue sections were placed in a phosphor-sensitive cassette for 48 h, after which the images were scanned, visualized, and quantified using a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics). Binding in the presence of 10−6 M oxytocin was considered nonspecific.

Heart Perfusion Studies.

Heart perfusion was performed as described by Lambert et al. (33). On the day of the study, the animals were heparinized (1,000 units i.p.) and anesthetized with pentobarbital (40 mg/kg i.p.). The hearts were rapidly excised and immediately placed in an ice-cold Krebs–Henseleit solution saturated with oxygen. Then, the heart was mounted on a perfusion system and perfused retrogradely via the aorta at 37°C and a constant pressure of 80 cm H2O (59 mmHg) according to the method of Langendorff. The Krebs–Henseleit perfusion solution (117 mmol/liter NaCl/4.7 mmol/liter KCl/2.5 mmol/liter CaCl2/1.2 mmol/liter KH2PO4/1.2 mmol/liter MgSO4/25 mmol/liter NaHCO3/0.5 mmol/liter Na2EDTA/11 mmol/liter dextrose) had a pH of 7.4 when gassed with 95% O2/5% CO2. The base of the pulmonary artery was incised to allow efficient drainage of the right ventricle. Heart rate was continuously monitored via electrodes placed at the apex of the heart and the aorta and connected to an AC current amplifier and recorded at a paper speed of 10 mm/sec (model 50-9927; Ealing Scientific, Canada). Coronary flow was measured every minute by timed collections of the effluent. At the end of a 15-min equilibration period, oxytocin (10−6 M) in the presence or in the absence of the same oxytocin antagonist (10−6 M and 10−7 M) employed in binding studies were added to the buffer and perfusion was maintained for an additional 25 min. Effluent samples were collected in polystyrene tubes containing 150 μl phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 150 μl EDTA, and 100 μl of 1% BSA. Samples were stored at −20°C until analysis.

Measurement of ANP and Brain Natriuretic Peptide (BNP).

In preliminary experiments, the heart effluent was extracted by Sep-Pak C18 cartridges (Millipore) and purified by HPLC liquid chromatography (34). The elution profile was identical to that of circulating rat ANP (Ser-99–Tyr-126), confirming the identity of ANP in the effluent. ANP in the samples (effluent) was directly measured by radioimmunoassay using an antibody that recognizes the carboxyl terminal of the molecule, as previously described by Gutkowska (34).

BNP was determined directly in heart effluent by radioimmunoassay using antibody against rat BNP purchased from Peninsula Laboratories (no. 1HC 9085). Rat BNP-32 (no. 9085; Peninsula Laboratories) was iodinated with 125INa using lactoperoxidase, and the radiolabeled tracer was purified by HPLC liquid chromatography as described for ANP (34). The antibody bound tracer was separated from free peptide by the second antibody precipitation in the presence of polyethylene glycol (6.25%). ANP and BNP contents in the perfusion effluent were corrected for the flow per minute.

Statistical Analysis.

Data storage, graphical output, and statistical analysis were assessed by one-way ANOVA using RS1 data analysis software (Bolt, Beranek & Newman). Statistical significance was taken as P < 0.05. All data are reported as mean ± SEM.

RESULTS

Identification of Oxytocin mRNA in Heart Tissue.

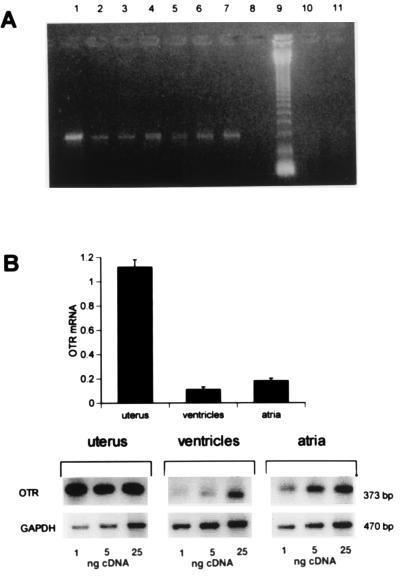

The presence of specific transcripts for oxytocin receptor in the rat heart was demonstrated by amplification of cDNA by PCR using specific oligonucleotide primers. Single bands were obtained after amplification of cDNA obtained from both rat atria, ventricles, aorta, as well as the uterus which was used as a positive control (Fig. 1). The size of these PCR amplification products corresponded to the expected molecular size of 373 bp. These bands were found by Southern blot analysis to hybridize to an independent oligonucleotide probe complementary to a segment of the amplified oxytocin receptor gene region (data not shown). This further attested to the specificity of the PCR product obtained. No amplification was obtained if total RNA of these organs was used as PCR template. Furthermore, we applied RT-PCR assay as a tool for the semiquantitative assessment of oxytocin receptor mRNA extracted from rat heart ventricles and atria. The level of amplified oxytocin receptor mRNA PCR product corrected to amplified GAPDH mRNA by RT-PCR was similar in atria and ventricles (Fig. 1). However, the oxytocin receptor mRNA level in the heart was low and at least 10 times lower than the oxytocin receptor mRNA level present in the uterus of a nonpregnant rat. Atrial concentrations were higher than those in the ventricles (P < 0.05).

Figure 1.

(A) Detection of oxytocin receptor mRNA in rat heart by RT-PCR. Total RNA from heart, uterus, or aorta was reverse transcribed and 25 ng of cDNA was subjected to PCR. The photograph presents oxytocin receptor RT-PCR products after electrophoresis on 2% agarose in ethidium bromide from the following targets: uterus (lane 1); uterus, reduced input of 5 ng of cDNA (lane 2); right atrium (lane 3); left atrium (lane 4); right ventricle (lane 5); left ventricle (lane 6); aorta (lane 7). No bands were obtained from control without cDNA/RNA, (lane 8), and after amplification by PCR, not reverse transcribed, uterus total RNA (lane 10), right atrium total RNA (lane 11). Lane 9: 123-bp ladder of GIBCO/BRL. (B) Relative quantification of oxytocin receptor mRNA from rat left atria and ventricles to oxytocin receptor mRNA present in rat uterus. (Lower) Representative PhosphorImager density bands of RT-PCR products of oxytocin receptor of 373 bp and GAPDH of 470 bp from cDNA of rat female left atria, left ventricles, and uterus cDNA amplified from various amounts (1, 5, and 25 ng) of cDNA under conditions assessing exponential PCR amplification. The histogram represents quantified values of scanned bands (mean ± SEM) of amplified oxytocin receptor cDNA normalized with respect to the bands of GAPDH cDNA in three independent experiments.

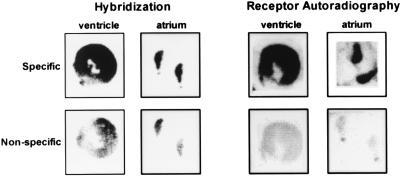

The presence of oxytocin receptor transcripts in rat heart was also shown by in situ hybridization on atrial and ventricular sections (Fig. 2), using the reverse PCR primer as a probe. The specificity of the hybridization was confirmed by inhibition of the hybridization signal following addition of an excess of unlabeled oligonucleotide. The hybridization signal was distributed throughout the examined atrial and ventricular slices.

Figure 2.

PhosphorImager scans of oxytocin receptor mRNA detected by in situ hybridization and oxytocin receptor binding sites revealed by autoradiography in heart atrial and ventricular sections. For in situ hybridization, the oxytocin receptor-specific 32P-labeled oligonucleotide has been applied. As a control for nonspecific hybridization the radiolabeled probe was mixed with a 100-fold excess of cold oligonucleotide. For autoradiography, the 125I-labeled oxytocin antagonist was applied to sections of atria and ventricles. As a control for nonspecific binding 10−6 M unlabeled oxytocin was added.

Oxytocin Binding Studies.

The oxytocin antagonist was labeled with 125I using chloramine-T as oxidant and purified by HPLC liquid chromatography using acetonitrile gradient (20–50%). In the direct binding of 125I oxytocin receptor antagonist to the heart membrane we experienced a low displacement with unlabeled oxytocin antagonist. This is probably due to the increased affinity of labeled antagonist to oxytocin receptors in comparison to that of the unlabeled peptides (E. Grazzini, personal communication). Using Scatchard analysis of saturation experiments, the binding characteristics in the membranes from whole mice heart were Kd = 541 pM and Bmax = 19.8 fmol/mg protein, values very similar to those found in rat kidney membranes (35).

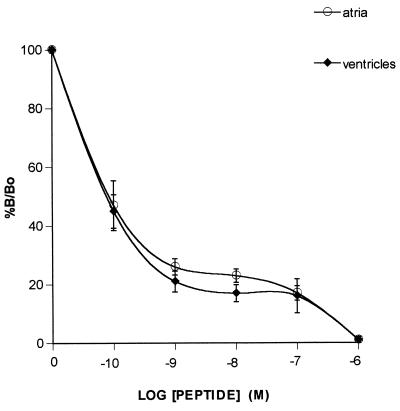

Further evaluation of rat heart oxytocin receptor was achieved by binding of 125I-labeled oxytocin receptor antagonist to atrial and ventricular slices by autoradiography and using a PhosphorImager for quantitative measurement of bound radioactivity. Fig. 3 illustrates curves obtained from the receptor assays of four rat ventricles and atria. The results are plotted as %B/Bo, where B and Bo represent, respectively, binding with and without cold peptide. Binding of 125I-labeled oxytocin antagonist was progressively inhibited by increasing concentrations of oxytocin. Kinetic parameters obtained from these curves showed that Bmax (atria, 1.39 ± 0.6 fmol/unit area; ventricles, 1.62 ± 0.4 fmol/unit area) and Kd (atria, 71 ± 74 pM; ventricles, 30.4 ± 26.5 pM) obtained were not different in the heart compartments.

Figure 3.

Competition curves obtained by the incubation of atrial and ventricular slices with 125I oxytocin antagonist in the presence or absence of increasing concentrations of oxytocin or antagonist. Curves are plotted as the concentration of unlabeled peptide vs. percent B/Bo, where Bo and B represent binding in the absence or presence of displacing peptides. Each point represents the mean ± SEM of duplicate determinations of both atria and ventricles from two female and two male rats.

Functional Characterization of Heart Oxytocin Receptors.

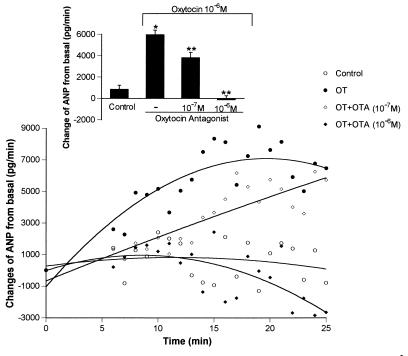

Perfusion of the rat heart with Krebs–Henseleit buffer resulted in nearly constant mean release of ANP measured during the 25 min experimental period (Fig. 4). ANP concentrations in the effluent during the first 5 min of perfusion after stabilization period were considered as basal values. Addition of oxytocin (10−6 pM) to the perfusion buffer stimulated significantly the release of ANP in the condition of constant perfusion pressure. The ANP release increased to a maximum at 15 min, which was sustained until the end of the experiment at 25 min. At 25 min of perfusion, the hearts released ANP at a rate of about 8 ng/min. The oxytocin receptor antagonist at concentrations of 10−6 and 10−7 M inhibited oxytocin-induced release in a dose-dependent manner. At the 10−7 M concentration the inhibition was highly significant, but it dissipated progressively during the experiment and was negligible in the final several minutes. The inhibition obtained with the 10−6 M concentration of oxytocin antagonist was complete from the outset and ANP output diverged to become lower than that of the control hearts at about 15 min and reached a minimum at 25 min that was significantly less (P < 0.001) than that of controls.

Figure 4.

Changes over time from initial release of ANP from perfused heart with buffer alone or with oxytocin (10−6 mol/liter) in the presence or absence of oxytocin antagonist, compound V1 (10−7 and 10−6 mol/liter). Data are the mean ± SEM of five to nine experiments each. Insert represents values obtained from the mean ± SEM of total ANP released by each of the various treatments over 25 min perfusion period. ∗, P < 0.001 versus control; ∗∗, P < 0.002 versus oxytocin (10−6 M).

BNP was detected in heart perfusates but oxytocin had no effect on BNP release. The basal BNP release during 25-min perfusion with buffer was 1,084 ± 226 pg/min, and did not increase in the presence of oxytocin (10−6 M) (1,046 ± 157 pg/min).

Perfusion of the heart with Krebs–Henseleit buffer for 25 min resulted in a gradual decrease in heart rate from basal values of 325 ± 10 beats/min (n = 8) to 305 ± 8 beats/min. The addition of oxytocin (10−6 M) to the buffer resulted in further decrease in the heart rate from basal 330 ± 12 beats/min (n = 9) to 288 ± 9 beats/min. This decrease in heart rate was observed in both groups; nevertheless, the decrease in heart rate in the presence of oxytocin 10−6 M was significantly greater than in buffer perfused hearts (P < 0.05). Oxytocin (10−6 M) in the presence of the oxytocin antagonist (10−6 M) did not affect heart rate (basal 323 ± 17 vs. 320 ± 10 beats/min) which shows that the antagonist totally reversed the bradycardia caused by oxytocin.

DISCUSSION

The present study demonstrates (i) that specific oxytocin binding sites are present in the rat heart, (ii) that the oxytocin receptor gene is expressed in rat atria and ventricles, and (iii) that the heart oxytocin receptors are functional because they mediate release of ANP.

The structures of oxytocin receptors have been elucidated by molecular cloning in tissues of various species: human (36), pig (37), rat (29), mouse (38), and sheep (39). Early data suggested the existence of one type of functional oxytocin receptor in various tissues. Studies with different oxytocin analogs showed the same ligand specificity in uterine and in adenohypophyseal lactotroph binding sites (40, 41). Numerous tissues express the oxytocin receptor, such as the uterus, mammary gland, kidney, pituitary lactotrophs, and brain. Our results extend these data by adding all chambers of the heart as sites of oxytocin receptor gene expression.

Characterization of oxytocin binding sites by autoradiography and in vitro binding studies suggested that there may be more than one oxytocin receptor subtype. The binding affinity of the oxytocin receptor in the hypothalamic ventromedial nucleus and hippocampus differs slightly from that in the uterus (42). Two different receptors have been postulated in the uterus on the basis of pharmacological differences (43). Our study shows that the same oxytocin receptor type is present in the heart as in the uterus. The RT-PCR product did not exhibit any extra bands that could indicate the presence of splicing, variations at the only intron that interrupts the coding region (29). Although our data do not preclude the presence of other oxytocin receptor subtypes in the heart, our results show clearly, in spite of the low expression of the transcript, that oxytocin receptors mediate the release of a potent cardiac hormone, ANP (44). The intensity of the autoradiographic heart oxytocin receptor binding in combination with similar results of our in situ hybridization studies strongly indicates the presence of oxytocin receptors directly in the areas of their synthesis.

Atrial stretch (44–46) and particularly increased heart rate (47) induces ANP release. In our experiments oxytocin enhanced ANP release even though heart rate was decreased. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that ANP released by activation of oxytocin receptors in the isolated heart mediates this negative chronotropic effect.

In our previous experiments in which we could measure not only cardiac rate but also force of contraction, we observed that both oxytocin and ANP had negative chronotropic and inotropic actions (18). The minimal effective concentration of ANP that induced these effects was lower than required for oxytocin. The negative chronotropic and inotropic effects of ANP have been documented in vivo (48, 49).

The mechanism of ANP release by oxytocin in isolated, perfused hearts is unknown. It has been shown that stimulation of oxytocin receptors leads to elevation of intracellular [Ca2+]. Increased [Ca2+] stimulate cellular exocytosis (50) and also stimulate ANP secretion by the heart (51). Recently, Laine et al. (52) showed in isolated perfused atria that ANP release by stretch increases at high extracellular [Ca2+], although stretch has no effect on ANP mRNA. However, stretch for 90 min, which did not increase BNP secretion, had a stimulatory effect on BNP mRNA. Although we have observed BNP release from the perfused heart, in our experiment oxytocin did not enhance BNP release significantly.

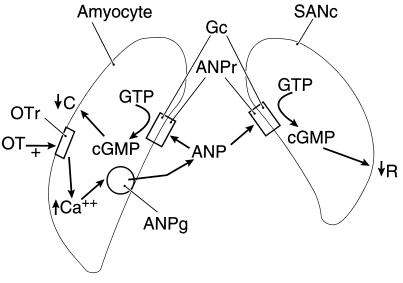

In preliminary studies (18), cGMP exerted negative chronotropic and inotropic effects on atria in vitro. Therefore, we hypothesize that ANP acts on particulate guanylyl cyclase in the sinoatrial node and atrial myocytes to increase intracellular cGMP which mediates the negative chronotropic and inotropic effects (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of proposed mechanism of oxytocin-induced ANP release in the right atrium. For detailed description, see Discussion. Amyocyte, atrial myoctye; SANc, sinoatrial node cell; OT, oxytocin; OTr, oxytocin receptor; ANPg, ANP secretory granule; ANPr, ANP receptor; Gc, guanylyl cyclase; C, contraction; R, heart rate; ↑, increase; ↓, decrease.

In conclusion, we propose a mechanism for control of ANP release: blood volume expansion by baroreceptor input to the brain stem evokes the release of oxytocin from the neurohypophysis that circulates to the heart and acts on oxytocin receptors to cause release of ANP. ANP then acts by its receptors in the right atrium to activate guanylyl cyclase. The released cGMP decreases the rate of cardiac contraction by an action on the sinoatrial node and, at the same time, decreases the force of contraction of the cardiac myocytes (Fig. 5). As the ANP reaches the right ventricle, it may possibly reduce the force of ventricular contraction. Because there are oxytocin receptors in the ventricle, these may cause local release of ANP which further decreases force of contraction.

ANP has a vasodilatory action mediated by cyclic GMP. In combination with the direct actions of ANP in the heart, a rapid reduction in circulating blood volume ensues, which may explain the fact that rapid volume expansion during 1 min in the rat is only accompanied by a transient release of ANP (1–5). The rapid reduction in the blood volume via ANP would remove the stimulus by the baroreceptors for further secretion of oxytocin and in turn ANP.

The released oxytocin and ANP circulate to the kidneys where we hypothesized that the natriuretic action of oxytocin is mediated by ANP (17, 19). Because oxytocin receptors have been discovered in various sites in the kidney, it is also possible that oxytocin may have an independent natriuretic action separable from that of ANP and that the two combine to produce the ensuing natriuresis. These actions coupled with a decrease in salt and water intake induced by ANP (53) and oxytocin (53) finally return body fluid volume to normal. We have already demonstrated that, with the concomitant release of oxytocin and ANP accompanied by a reduction in vasopressin release following isotonic volume expansion (17), oxytocin will induce ANP release in vivo (17) and in vitro (18) and that an oxytocin antagonist can block ANP release in vitro (ref. 18, and the present paper) and suckling-induced release of ANP in vivo (17). To prove the functional significance of our concept requires the demonstration that an oxytocin antagonist can block ANP release from volume expansion. Because oxytocin antagonists reduced ANP release below control levels in this and our previous experiments (18), it appears likely that intracardiac oxytocin may play a role in ANP release.

In our preliminary results, we observed an increase in cardiac oxytocin receptors in pregnancy (unpublished data). The plasma concentrations of both oxytocin and ANP are increased after parturition. Consequently, we have developed the hypothesis that oxytocin stimulates the release of ANP that is responsible for the massive diuresis observed postpartum. Research in our laboratory is in progress to substantiate this hypothesis.

In summary, the present study demonstrates functional oxytocin receptors in the heart that mediate the release of ANP. Our results support the concept that oxytocin and ANP act in concert in the control of body fluid as well as in cardiovascular homeostasis.

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to Céline Coderre, Nathalie Charron, and Marie-France Legault for their technical contributions. We also thank Mrs. Magali Désévaux-Domin, Mr. Jason Holland, and Ms. Judy Scott for their excellent secretarial assistance. These studies were supported by Medical Research Council of Canada Grants MT-10337 and MT-11674 and grants from the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada and the Kidney Foundation of Canada (to J.G.), and National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grant DK-43900 and National Institute of Mental Health Grant MH-51853 (to S.M.M.).

ABBREVIATIONS

- ANP

atrial natriuretic peptide

- RT-PCR

reverse transcription–PCR

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- BNP

brain natriuretic peptide

References

- 1.Antunes-Rodrigues J, Picanco-Diniz D W L, Favaretto A L V, Gutkowska J, McCann S M. Neuroendocrinology. 1993;58:696–700. doi: 10.1159/000126611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baldissera S, Menani J W, Sotero dos Santos L F, Favaretto A L V, Gutkowska J, Turrin M Q A, McCann S M, Antunes-Rodrigues J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:9621–9625. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.23.9621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Antunes-Rodrigues J, Marubayashi U, Favaretto A L V, Gutkowska J, McCann S M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:10240–10244. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.21.10240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Antunes-Rodrigues J, Ramalho M J, Reis L C, Picanco-Diniz D W L, Favaretto A L V, Gutkowska J, McCann S M. Neuroendocrinology. 1993;58:701–708. doi: 10.1159/000126612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Antunes-Rodrigues J, Ramalho M J, Reis L C, Menani J V, Turrin M Q, Gutkowska J, McCann S M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:2956–2960. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.7.2956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crandall M E, Gregg C M. Neuroendocrinology. 1986;44:439–445. doi: 10.1159/000124684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Januszewicz P, Thibault G, Garcia R, Gutkowska J, Genest J, Cantin M. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1985;134:652–658. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(86)80469-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sonnenberg H, Veress A T. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1984;124:443–449. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(84)91573-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manning P T, Schwartz D, Katsube N C, Holmberg S W, Needleman P. Science. 1985;229:395–397. doi: 10.1126/science.2990050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heller H. In: Occurrence, Storage and Metabolism of Oxytocin. Caldeyro-Barcia R, Heller H, editors; Caldeyro-Barcia R, Heller H, editors. New York: Pergamon; 1961. pp. 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Verbalis J G, Blackburn R E, Hoffman G E, Stricker E M. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1995;395:209–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caldwell J D, Prange A J, Jr, Pedersen C A. Neuropeptides. 1986;7:175–189. doi: 10.1016/0143-4179(86)90093-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pedersen C A, Ascher J A, Monroe Y L, Prange A J., Jr Science. 1982;216:648–650. doi: 10.1126/science.7071605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Engelmann M, Wotjak C T, Neumann I, Ludwig M, Landgraf R. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1996;20:341–358. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(95)00059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Conrad K P, Gellai M, North W G, Valtin H. Am J Physiol. 1986;251:F290–F296. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1986.251.2.F290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang W, Lee S L, Sjoquist M. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:R634–R640. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1995.268.3.R634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haanwinckel M A, Elias L K, Favaretto A L V, Gutkowska J, McCann S M, Antunes-Rodrigues J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7902–7906. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Favaretto, A. L. V., Ballejo, G., Albuquerque-Araujo, W. I. C., Gutkowska, J., Antunes-Rodrigues, J. & McCann, S. M. (1997) Peptides, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.McCann S M, Franci C, Gutkowska J, Favaretto A L, Antunes-Rodrigues J. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1996;213:117–127. doi: 10.3181/00379727-213-44044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zingg H H. Baillieres Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;10:75–96. doi: 10.1016/s0950-351x(96)80314-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lefebvre D L, Lariviere R, Zingg H H. Biol Reprod. 1993;48:632–639. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod48.3.632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adan R A, Van Leeuwen F W, Sonnemans M A, Brouns M, Hoffman G, Verbalis J G, Burbach J P. Endocrinology. 1995;136:4022–4028. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.9.7649111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Larcher A, Neculcea J, Chu K, Zingg H H. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1995;114:69–76. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(95)03643-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu W X, Verbalis J G, Hoffman G E, Derks J B, Nathanielsz P W. Endocrinology. 1996;137:722–728. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.2.8593823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tribollet E, Barberis C, Dreifuss J J, Jard S. Kidney Int. 1988;33:959–965. doi: 10.1038/ki.1988.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patchev V K, Schlosser S F, Hassan A H, Almeida O F. Neuroscience. 1993;57:537–543. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crowley R S, Insel T R, O’Keefe J A, Kim N B, Amico J A. Endocrinology. 1995;136:224–231. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.1.7828535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Quinones-Jenab V, Jenab S, Ogawa S, Adan R A M, Burbach J P H, Pfaff D W. Neuroendocrinology. 1997;65:9–17. doi: 10.1159/000127160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rozen F, Russo C, Banville D, Zingg H H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:200–204. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.1.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Breton C, Pechoux C, Morel G, Zingg H H. Endocrinology. 1995;136:2928–2936. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.7.7540544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wisden W, Morris B J. In: In Situ Hybridization Protocols for Brain. Wisden W, Morris B J, editors; Wisden W, Morris B J, editors. New York: Academic; 1997. pp. 9–30. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bradford M M. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–252. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lambert C, Mossiat C, Tanniere-Zeller M, Maupoil V, Rochette L. Cardiovasc Res. 1990;24:653–658. doi: 10.1093/cvr/24.8.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gutkowska J. Nucl Med Biol. 1987;14:323–331. doi: 10.1016/0883-2897(87)90009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Breton C, Neculcea J, Zingg H H. Endocrinology. 1996;137:2711–2717. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.7.8770890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kimura T, Tanizawa O, Mori K, Brownstein M J, Okayama H. Nature (London) 1992;356:526–529. doi: 10.1038/356526a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gorbulev V, Buchner H, Akhundova A, Fahrenholz F. Eur J Biochem. 1993;215:1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb18000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kubota Y, Kimura T, Hashimoto K, Tokugawa Y, Nobunaga K, Azuma C, Saji F, Murata Y. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1996;124:25–32. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(96)03923-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Riley P R, Flint A P, Abayasekara D R, Stewart H J. J Mol Endocrinol. 1995;15:195–202. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0150195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Antoni F A. Endocrinology. 1986;119:2393–2395. doi: 10.1210/endo-119-5-2393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chadio S E, Antoni F A. J Endocrinol. 1989;122:465–470. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1220465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Audigier S, Barberis C. EMBO J. 1985;4:1407–1412. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb03794.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chan W Y, Chen D L, Manning M. Endocrinology. 1993;132:1381–1386. doi: 10.1210/endo.132.3.8382600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dietz J R. Am J Physiol. 1984;247:R1093–R1096. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1984.247.6.R1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lang R E, Tholken H, Ganten D, Luft F C, Ruskoaho H, Unger T. Nature (London) 1985;314:264–266. doi: 10.1038/314264a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schiebinger R J, Linden J. Circ Res. 1986;59–1:105–109. doi: 10.1161/01.res.59.1.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bilder G E, Siegl P K, Schofield T L, Friedman P A. Circ Res. 1989;64:799–805. doi: 10.1161/01.res.64.4.799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rankin A J, Swift F V. Pflügers Arch Eur J Physiol. 1990;417:353–359. doi: 10.1007/BF00370652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lambert C, Ribuot C, Robichaud A, Cusson J R. Eur J Pharmacol. 1994;252:245–252. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(94)90169-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Knight D E, von Grafenstein H, Athayde C M. Trends Neurosci. 1989;12:451–458. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(89)90095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ruskoaho H, Toth M, Lang R E. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1985;133:581–588. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(85)90945-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Laine M, Id L, Vuolteenaho O, Ruskoaho H, Weckstrom M. Pflügers Arch Eur J Physiol. 1996;432:953–960. doi: 10.1007/s004240050222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gutkowska J, Antunes-Rodrigues J, McCann S M. Physiol Rev. 1997;77:465–515. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1997.77.2.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]