Abstract

This randomised phase III study in advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients was conducted to compare vinorelbine/carboplatin (VC) and gemcitabine/carboplatin (GC) regarding efficacy, health-related quality of life (HRQOL) and toxicity. Chemonaive patients with NSCLC stage IIIB/IV and WHO performance status 0–2 were eligible. No upper age limit was defined. Patients received vinorelbine 25 mg m−2 or gemcitabine 1000 mg m−2 on days 1 and 8 and carboplatin AUC4 on day 1 and three courses with 3-week cycles. HRQOL questionnaires were completed at baseline, before chemotherapy and every 8 weeks until 49 weeks. During 14 months, 432 patients were included (VC, n=218; GC, n=214). Median survival was 7.3 vs 6.4 months, 1-year survival 28 vs 30% and 2-year survival 7 vs 7% in the VC and GC arm, respectively (P=0.89). HRQOL, represented by global QOL, nausea/vomiting, dyspnoea and pain, showed no significant differences. More grade 3–4 anaemia (P<0.01), thrombocytopenia (P<0.01) and transfusions of blood (P<0.01) or platelets (P<0.01) were observed in the GC arm. There was more grade 3–4 leucopoenia (P<0.01) in the VC arm, but the rate of neutropenic infections was the same (P=0.87). In conclusion, overall survival and HRQOL are similar, while grade 3–4 toxicity requiring interventions are less frequent when VC is compared to GC in advanced NSCLC.

Keywords: non-small-cell lung cancer, vinorelbine, gemcitabine, palliative, quality of life, survival

Lung cancer remains the leading cause of cancer death worldwide, and the incidence is increasing (Jemal et al, 2006). Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for about 80% of lung cancer cases, and the majority presents with locally advanced or metastatic disease (Ries et al, 2006). The patient population is large, median age high and comorbidity often considerable. Optimising the treatment is a challenge. Any systemic anticancer therapy to this group should be effective, tolerable and improve quality of life (QOL).

In the meta-analysis from 1995 (Alberti, 1995) demonstrated superiority of chemotherapy over best supportive care in advanced NSCLC. Since then, new agents like vinorelbine, gemcitabine, taxans and irinotecan, often referred to as third-generation drugs, have established their role in this disease. The third-generation agents have been compared to older regimens in various ways. Platinum-based doublets with a third-generation drug have proven more effective than monotherapy, and equally effective, but less toxic, than three-drug regimens (Bunn, 2002). Two-drug combination regimens have been established as recommended first-line chemotherapy in advanced NSCLC (Pfister et al, 2004). Although slightly inferior to cisplatin (Hotta et al, 2004), carboplatin is advocated a valuable alternative in the palliative treatment of NSCLC. Which third-generation non-platinum agent to choose is, however, still debated.

Vinorelbine/carboplatin (VC) and gemcitabine/carboplatin (GC) are both third-generation combinations used in the treatment of NSCLC. Vinorelbine in combination with a platinum-compound is established as treatment of advanced NSCLC (Kelly et al, 2001; Scagliotti et al, 2002; Plessen et al, 2006). The gemcitabine/platinum combination is widely used and reported to be effective and tolerable (Le Chevalier et al, 2005). The aim of the present study was to compare VC and GC with respect to efficacy, health-related quality of life (HRQOL) and toxicity in stage IIIB/IV NSCLC patients. The inclusion criteria were liberal, reflecting the everyday clinical situation. To our knowledge, this is the first randomised direct comparison of these two regimens.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

In this national, multicentre and randomised phase III trial, chemonaive patients with histologically or cytologically confirmed NSCLC stage IIIB or IV, not candidates for curative treatment, were included. Eligibility criteria were WHO performance status (PS) 0–2 and ability to understand oral and written study information. No upper age limit was defined. White blood-cell count >3.0 × 109 cells l−1, platelet count >100 × 109 cells l−1, serum creatinin<1.5 times upper reference limit and bilirubin and serum transaminase levels<2 times upper limits were required. Exclusion criteria were other active malignancies, pregnancy, or breast feeding.

The Regional Ethical Review Board, the Norwegian Social Science Data Services and the Norwegian Medicines Agency have approved the study.

Baseline investigation

At study entry, all patients underwent clinical examinations, laboratory measures, chest X-ray and chest CT scan including upper abdomen. PS, body weight and height were registered. Patients were staged according to the clinical stage classification from 1997 (Mountain, 1997).

Randomisation

After signing the informed consent and completing the baseline HRQOL form, patients were randomised to receive VC or GC, stratifying for PS 0–1 vs 2 and stage IIIB vs IV. Randomisation was performed by phone or fax to the randomisation centre (Clinical Cancer Research Office, University Hospital of Northern Norway).

Chemotherapy

In each arm, three courses of chemotherapy, primarily administered on an outpatient basis, were given at 3-week cycles. Carboplatin was administered on day 1, and vinorelbine or gemcitabine on days 1 and 8 in each course. For both regimens, the carboplatin dose was calculated by the Chatelut formula (Chatelut et al, 1995) using AUC=4, which approximates Calvert (Calvert et al, 1989) AUC=5.

Carboplatin in 500 ml 5% glucose was administered as a 1-h infusion. Vinorelbine 25 mg m−2 in 100 ml 5% glucose was given as a 10 min i.v. infusion, whereas gemcitabine 1000 mg m−2 in 250 ml 0.9% NaCl was administered i.v. for 30 min. Patients ⩾75 years received 75% of standard doses. Antiemetics were given before chemotherapy.

Blood counts were assessed weekly. If moderate haematological toxicity (WBC: 2.5−2.99 × 109 l−1 and/or platelets: 75–99 × 109 l−1 occurred at days 1 and 8, doses were reduced by 25%. In case of severe haematological toxicity (WBC<2.5 × 109 l−1 and/or platelets< 75 × 109 l−1), chemotherapy was postponed for 1 week and further doses were reduced by 25%. If treatment was associated with febrile leucopoenia or leucopoenia-associated infection, chemotherapy was postponed until clinical recovery and further doses were reduced by 25%. Treatment was discontinued in case of disease progression, unacceptable toxicity or on patient's request.

Patient follow-up

At start of each treatment cycle (weeks 0, 3 and 6) and at the 8-weekly follow-up visits (weeks 9, 17, 25, 33, 41 and 49), patients underwent clinical examinations, evaluations of PS, assessments of body weight, laboratory tests and chest X-rays. For evaluation of disease progression, chest CT was performed when indicated.

Haematological toxicity was graded according to the WHO toxicity criteria (WHO, 1979). Transfusions, bleedings, leucopoenic infections, use of G-CSF or erythropoietin and hospital admissions due to treatment toxicity were registered. The use of radiotherapy or second-line chemotherapy was recorded.

Site visits were performed at hospitals, which included ⩾20 patients. Otherwise, missing data were retrieved through phone or mail to the patient's physician.

Assessment of HRQOL

HRQOL was assessed using the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality of Life Questionnaire (QLQ)-C30 (Aaronson et al, 1993) and the lung cancer-specific module QLQ-LC13. (Bergman et al, 1994) The QLQ-C30 measures fundamental aspects of HRQOL and symptoms commonly reported by cancer patients in general, while the QLQ-LC13 addresses symptoms specifically associated with lung cancer and its treatment.

Baseline HRQOL questionnaires were completed before the first chemotherapy cycle. Follow-up questionnaires (before each cycle and every 8 weeks until 49 weeks) were mailed to the patients from the randomisation office. In lack of response, one reminder was mailed after 14 days.

Study endpoints

The main endpoint was overall survival. Further endpoints were patient-assessed HRQOL and treatment toxicity including required interventions. Global QOL, nausea/vomiting, dyspnoea and pain during the first 17 weeks were pre-defined as the primary HRQOL items of interest.

Global QOL is an important general measure, nausea/vomiting a common side effect of chemotherapy and dyspnoea a severe symptom in lung cancer. Pain is frequent in stage IV disease with a significant impact on QOL.

Statistical considerations

Estimation of study size was based both on survival and HRQOL measures. To detect a difference in survival of 11% or HRQOL of 15% between the groups, provided a power of 80% and a significance level of 0.05 using two-sided tests, 380 patients were required. Based on a 5% dropout, the required patient number was 400.

Survival, defined as time from randomisation to the date of death, was compared using Kaplan–Meier estimates and the log-rank test.

HRQOL items for global QOL, nausea/vomiting, dyspnoea and pain were scored for each patient according to the EORTC QLQ-C30 scoring manual (Fayers et al, 2001). All HRQOL item scores range from 0 to 100. A high score in global QOL represents a good QOL, whereas a high symptom-scale score represents more symptoms. For group comparisons of baseline scores during and after chemotherapy, and changes in scores from baseline, the Mann–Whitney U-test was used. A mean change of ⩾10 was considered clinically relevant and significant (Osoba et al, 1998). The AUC from baseline to week 17 was compared using a two-sided t-test. Group differences consistent across all three methods of analysis, or yielding a P-value ⩽0.01, were considered significant.

Differences in haematological toxicity and registered interventions were analysed using two-sided t-test and χ2 tests.

RESULTS

Patients

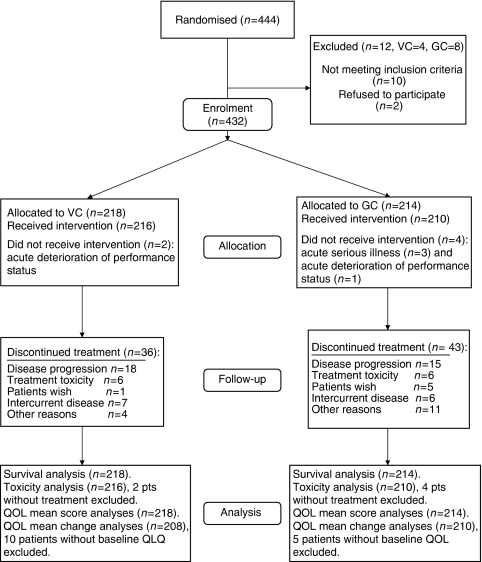

Between October 2003 and December 2004, 444 patients from 33 hospitals in Norway were randomised to receive VC (n=222) or GC (n=222). The median follow-up was 31 months (range 24–39 months). Ten patients were randomised prematurely and later failed to meet the inclusion criteria (SCLC, n=2; stage IIB–IIIA disease, n=5; malignant melanoma, n=1; carcinoid, n=1; granulomatous disease, n=1). Furthermore, two patients were randomised without giving their consent. In total, 432 patients, 218 in the VC and 214 in the GC arm, met the eligibility criteria and constituted the intention-to-treat population for the primary end-point analysis. This accounts for grossly 40% of all stage IIIB–IV NSCLC patients diagnosed in Norway during the study period (personal communication, The Norwegian Cancer Registry). Nine hospitals recruited ⩾20 patients, constituting 70% of the total patient population. The patient flow chart is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow of patients through each stage of the study.

Patient characteristics according to treatment groups are given in Table 1. For all patients, median age was 67 years, 20% ⩾75-years old, 61% male, 71% had stage IV disease, 28% PS 2 and 48% adenocarcinoma. The study arms were well balanced with respect to demographic, clinical and histological characteristics.

Table 1. Patient characteristics at inclusion according to treatment arm.

|

VIN/CARBO

|

GEM/CARBO

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

(n=218)

|

(n=214)

|

||||

| Characteristics | n | % | n | % | P |

| Age (years) | |||||

| Median | 67 | 67 | 0.92 | ||

| Range | 37–86 | 37–85 | |||

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 90 | 41 | 78 | 36 | 0.30 |

| Male | 128 | 59 | 136 | 64 | |

| Performance status | |||||

| 0/1 | 156 | 72 | 153 | 71 | 0.99 |

| 2 | 62 | 28 | 61 | 29 | |

| Extent of disease | |||||

| Stage IIIB | 65 | 30 | 60 | 28 | 0.68 |

| Stage IV | 153 | 70 | 154 | 72 | |

| Histology | |||||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 58 | 26 | 52 | 24 | 0.65 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 108 | 50 | 101 | 47 | |

| Large cell carcinoma | 11 | 5 | 19 | 9 | |

| Other | 41 | 19 | 42 | 20 | |

Chemotherapy completion

The mean number of chemotherapy courses was 2.7 for the VC and 2.6 for the GC arm. Reasons for treatment termination are given in Figure 1. In the VC arm, 180 patients (83%) received all three cycles, 21 (10%) two cycles, 15 (7%) one cycle and two (1%) no chemotherapy. In the GC arm, the corresponding numbers were 167 (78%), 17 (8%), 26 (12%) and 4 (2%).

Delayed or cancelled vinorelbine or gemcitabine at day 8 due to haematological toxicity was observed in 9.3% (delayed 4.6%; not given 4.8%) of the VC and 18.1% (delayed 10.2%; not given 7.9%) of the GC group (P=0.03). Time exceeding 24 days between the main chemotherapy courses occurred in 15% of VC and 23% of GC patients (P=0.06).

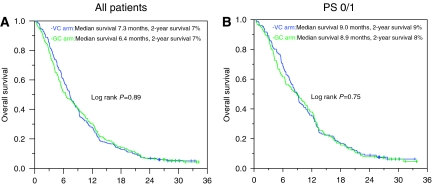

Survival

All enrolled patients were included in the survival analyses (n=432). There was no difference in overall survival between the treatment arms (P=0.89; Figure 2A). The median survival was 7.3 vs 6.4 months and the 1- and 2-year survival were 28 and 7% vs 30 and 7%, respectively, for the VC and GC arm. Excluding the PS 2 patients, the corresponding median survival was 9.0 vs 8.9 months, while the 1- and 2-year survival were 35 and 9% vs 38 and 8%, respectively (P=0.75; Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Overall survival according to treatment arms. (A) Survival for all study patients; VC (n=218, censored n=12) and GC (n=214, censored=11). (B) Survival for PS 0/1 patients; VC (n=156, censored n=11) and GC (n=153, censored n=9).

The cause of death was recorded in 324 patients. As reported by the local investigators, 282 deaths (87%) were caused by lung cancer. Six deaths were associated with chemotherapy side effects (VC, n=2; GC, n=4), while the remaining (n=36) were classified as other causes.

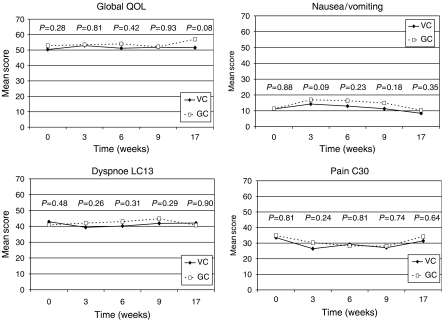

QOL

The compliance rate with respect to completion of the HRQOL questionnaires was 95 and 98% at baseline and declined to minimum 61 and 60% during the 49-week follow-up for the VC and GC arm, respectively. Mean score analyses were performed for all patients, while only patients with completed baseline HRQOL questionnaires were included in the mean change analyses (VC, n=207; GC, n=210). The AUC was analysed for patients who had completed all five questionnaires during the period of interest (VC, n=111; GC, n=97). Mean scores for global QOL, nausea/vomiting, dyspnoea and pain are shown in Figure 3. Mean scores at baseline and weeks 3, 6, 9 and 17 were compared between the treatment arms. The GC arm tended to have slightly worse scores than the VC arm for nausea/vomiting and dyspnoea during therapy, but there were no significant differences for any of the four examined HRQOL items. Neither was there any difference between the VC and GC arm with respect to mean change of scores or AUC from baseline to week 17 (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Health-related quality of life scores (weeks 0–17) for global QOL, nausea/vomiting, pain, and dyspnoea according to treatment arm.

Toxicity and required interventions

Data on haematological toxicity are presented in Table 2. More grade 3–4 anaemia and thrombocytopenia were observed in the GC arm (P<0.01), while there was more grade 3–4 leucopoenia in the VC arm (P<0.01). Other treatment side effects and required interventions are given in Table 3. More patients in the GC arm needed blood transfusions (P<0.01) or platelets (P=0.04), while there was no difference between the arms with respect to neutropenic infections (P=0.98). Patients in the GC arm tended to more frequent hospital admissions (P=0.10).

Table 2. Haematological toxicity according to treatment arm.

|

VIN/CARBO

|

GEM/CARBO

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

n=216

|

n=210

|

||||||||

|

Grade 3

|

Grade 4

|

Grade 3

|

Grade 4

|

||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | P | |

| Anaemia | 13 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 35 | 16 | 7 | 3 | <0.01 |

| Leucopoenia | 82 | 38 | 16 | 7 | 57 | 27 | 6 | 3 | <0.01 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0.5 | 53 | 25 | 41 | 19 | <0.01 |

Table 3. Side effects and interventions secondary to haematological toxicities according to treatment arm.

| Characteristics | VC | GC | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thrombocytopenic bleeding | |||

| No. of patients bleeding | 1 | 11 | <0.01 |

| Bleeding/patient | 0.004 | 0.05 | |

| Missing (n) | 3 | 7 | |

| Neutropenic infections | |||

| No. of infections | 46 | 48 | 0.98 |

| Infections/patient | 0.21 | 0.21 | |

| Missing (n) | 6 | 8 | |

| Hospital admissions | |||

| No. of admissions | 80 | 102 | 0.10 |

| Admission/patient | 0.39 | 0.52 | |

| Missing (n) | 10 | 9 | |

| Blood transfusions | |||

| No. units | 136 | 283 | <0.01 |

| Units/patient | 0.65 | 1.36 | |

| Missing (n) | 2 | 3 | |

| Platelet transfusions | |||

| No. of units | 5 | 30 | 0.02 |

| Units/patient | 0.03 | 0.15 | |

| Missing (n) | 16 | 16 | |

Anticancer treatment beyond the trial regimens

Data on second-line chemotherapy and palliative radiotherapy were available for 95% of the patients and showed no differences between the treatment arms. In the VC vs GC arm, 46 vs 39% (P=0.08), 32 vs 25% (P=0.23) and 15 vs 13% (P=0.45) received palliative radiotherapy, second-line chemotherapy, or both.

DISCUSSION

This randomised trial demonstrates that VC, when compared to GC in NSCLC stage IIIB and IV, is equally effective (median and 2-year survival 7.3 months and 7% vs 6.5 months and 7%), but causes significantly less grade 3–4 anaemia and thrombocytopenia.

The main strength of the study is the highly representative patient population. Roughly 40% of all stage IIIB and IV NSCLC patients diagnosed in Norway during the study period were included. Nearly one-third of the included patients had PS 2. Further, the treatment arms were equivalent with respect to chemotherapy delivery schedule, facilitating a direct comparison of the two regimens. The limited number of patients (⩽5) included at each of the smaller hospitals may be a weakness, but constituted only 5% of the study population.

Vinorelbine combined with platinum has proved to be one of the most promising regimens in the adjuvant setting (Douillard et al, 2006), and vinorelbin-based therapy is established as a valuable alternative in treatment of advanced NSCLC (Plessen et al, 2006). Gemcitabine is more frequently used in palliative treatment of NSCLC. In a meta-analysis including 4556 patients from 13 randomised trials, gemcitabine-platinum doublets were found to be slightly superior to the non-gemcitabine combinations regarding progression-free survival only (Le Chevalier et al, 2005). When compared to third-generation platinum-based doublets, the difference was no longer significant (HR 0.93, CI 0.86–1.01).

Whether carboplatin may substitute cisplatin in two-drug platinum-based combinations for advanced NSCLC was investigated by Hotta et al (2004) in a meta-analysis including 2945 patients. It was concluded that cisplatin combined with a third-generation agent produced a survival advantage of 11% when compared to carboplatin and the same third-generation agent. The recent CISCA (cisplatin vs carboplatin) meta-analysis (Ardizzoni et al, 2006), an individual patient data meta-analysis presented at ASCO 2006, found cisplatin-based chemotherapy superior to carboplatin-based with respect to response rate, but not overall survival. However, in palliative treatment of NSCLC, patient QOL, treatment toxicity and time hospitalised are considered more relevant issues.

The median survival in our study is somewhat lower when compared to other phase III trials. For vinorelbine/platinum combinations, recent phase III studies have yielded median survival data ranging from 6.5 to 11 months (Wozniak et al, 1998; Kelly et al, 2001; Scagliotti et al, 2002; Fossella et al, 2003; Gebbia et al, 2003; Georgoulias et al, 2005; Martoni et al, 2005; Tan et al, 2005; Plessen et al, 2006). In the gemcitabine/platinum meta-analysis (Le Chevalier et al, 2005), median survival in the gemcitabine group was 9 months, reflecting the mean value for a number of studies (Le Chevalier et al, 1994; Cardenal et al, 1999; Sandler et al, 2000; Scagliotti et al, 2002; Schiller et al, 2002; Alberola et al, 2003; Gebbia et al, 2003; Smit et al, 2003; Zatloukal et al, 2003; Martoni et al, 2005; Rudd et al, 2005; Sederholm et al, 2005). Our shorter median survival is possibly explained by the high proportion of patients with PS 2 (28%), which is the most powerful predictor of survival in NSCLC patients (Stanley, 1980). When PS 2 patients were excluded from our analysis, the median survival was 9.0 vs 8.9 months in the VC and GC arm, respectively. Nevertheless, this study shows that overall survival after VC is equivalent to GC in an unselected lung cancer patient population mimicking the everyday clinical setting.

The optimal duration of palliative therapy is debated. The 2003 update of the ASCO guidelines recommended limiting chemotherapy to six cycles in general and stopping treatment after four cycles in stage IV patients who do not respond to treatment. This limitation was based on a British trial comparing three vs six courses of mitomycin, vinblastine and cisplatin (Smith et al, 2001), and a US study comparing four courses of carboplatin/paclitaxel with the same combination given until progression (Socinski et al, 2002). Neither trial showed benefits from longer treatment duration. Additionally, the Norwegian Lung Cancer Study Group recently published a study comparing three vs six courses of VC, showing no benefit from the longer treatment (Plessen et al, 2006). Consequently, we chose three course regimens for the current study. The selected carboplatin and vinorelbine doses and schedule in the present trial were based on this Norwegian study. The gemcitabine dose resulted from a pilot study and the experience from a phase II study (Kortsik et al, 2003). As 83% of the patients in the VC arm and 78% in the GC arm tolerated all three courses, doses and schedules appear appropriate for the study population.

The higher rate of leucopoenia experienced in the VC arm (45 vs 30%) did not result in higher infection rates and was mainly laboratory toxicity without direct impact on patients' lives. In contrast, the markedly higher incidence of grade 3–4 anaemia (19 vs 6%) and thrombocytopenia (44 vs 3%) in the GC arm led to additional symptoms and significantly more frequent transfusions of blood products, requiring hospitalisation and further costs. Haematological toxicity following VC treatment of 159 advanced NSCLC patients was reported by Tan et al (2005). In this study, the vinorelbine dose was higher (30 mg m−2), and inclusion criteria were more restricted with Karnofsky PS⩾80 and age <75. Leucopoenia was observed less often (22%) and grade 3–4 anaemia significantly more frequent (21%). The latter might be explained by the somewhat higher vinorelbine dose. In the previous Norwegian NSCLC study (Plessen et al, 2006), the inclusion criteria were similar and 150 patients received VC chemotherapy doses and schedule identical to the present study. Plessen et al (2006) reported slightly less frequent grade 3–4 leucopoenia (35%), whereas the frequencies of grade 3–4 anaemia and thrombocytopenia were similar. In a Swedish phase III study in advanced NSCLC (Sederholm et al, 2005), GC treatment yielded the same leucopoenia and thrombocytopenia rates as in our study, but grade 3–4 anaemia was seen in only 5% of the patients. The age distribution was comparable to our study, while the proportion of PS 2 patients was smaller and fewer patients had metastatic disease. Thus, our toxicity data are consistent with previous studies and support the chosen chemotherapy dosage.

The overall compliance rate regarding completion of the HRQOL forms during the study period was 88%, which is equal or better than previous lung cancer studies using the EORTC questionnaire (Cardenal et al, 1999; Scagliotti et al, 2002; Gridelli et al, 2003a, 2003b; Smit et al, 2003; Rudd et al, 2005; Sederholm et al, 2005; Plessen et al, 2006). However, the higher frequency of toxicity and interventions after GC therapy were not reflected in any HRQOL difference between the treatment arms. Consistent with the discussion by Scagliotti et al (2002), regarding their comparison of gemcitabine-cisplatin and vinorelbine-cisplatin in advanced NSCLC, the timing of HRQOL questionnaire completion at the end of each cycle may mask the effect of acute chemotherapy-induced toxicity.

In conclusion, this randomised comparison of the two platinum-based doublets with vinorelbine or gemcitabine showed equivalent survival and HRQOL, while clinically relevant toxicity was more frequent in the GC arm. To minimise toxicity-related burdens for patients, the VC combination appears an appropriate choice for palliative treatment of advanced NSCLC.

Acknowledgments

The contribution by all institutions including patients in this trial is greatly acknowledged. The statistical advice from Bjørn Straume, Institute of Community Medicine and University of Tromsø is appreciated. Randomisation and enrolment were made possible by the Clinical Cancer Research Office, University Hospital of Northern Norway.

Appendix

INVESTIGATORS AT STUDY CENTRES

Ø Furnes, Hammerfest Hospital; PK Skorpen, U Spreng, Stokmarknes Hospital; HH Strøm, P Vanke, Sandessjøen Hospital; M Onkiehong, Rana Hospital; P Reckert, A Boeckmann, Narvik Hospital; A Fossli, B Heermann, L Strauman, Lofoten Hospital; M Jordhøy, A Reigstad, O Alexandersen, TB Nymark, Nordland Hospital Bodø; NG Zafran, Harstad Hospital; E Heitmann, T Børvik, N Ritland, U Aasebø, M Vold, M Petersen, P Røyset, University Hospital of Northern Norway Tromsø; M Heibert, RS Brandsæg, Namsos Hospital; T Naustdal, H Ellekjær, PA Oppegaard, R Kibsgaard, Ø Brenna, H dalen, Levanger Hospital; OF Aasen, I Eskeland, Volda Hospital; B Jakobsen, Molde Hospital; O Herlofsen, Kristiansund Hospital; F Majeed, F Wammer, JÅ Longva, H Fremstad, Erik Liaaen,, Ålesund Hospital; H Hjelde, AS von Krogh, AK Knudsen, S Sundstrøm, E Titova, B Grønberg, T Amundsen, H Hoven, H Tøndel, D Kulosmann, RA Walstad, T Tollåli, M Øyre, A Prestmo, S Sørhaug, S Osen, M Thronæs, H Enger, St Olavs University Hospital Trondheim, A Totland, S Fluge, K Valen, Haugesund Hospital; A Ruud, O Garpestad, M Kosaca, Stavanger University Hospital; CB Alm, Voss Hospital; C von Plessen, Ø Fløtten, H Markova, T Vigander, O Mørkve, A Thelle, A van Lessen, Haukeland University Hospital Bergen; H Rolke, F Gallefoss, G Hoven, Sørlandet Hospital Kristiansand; V Lejlic, E Røyndstrand, Sørlandet hospital Arendal; O Øygarden, Blefjell Hospital Rjukan; Ø Fløtterød, W Gustavsson, Telemark Hospial; OK Andersen, K Semb, Vestfold Hospital Tønsberg; V Stenberg, T Bjørge, H Ranfelt, Ringerike Hospital; Å Skår, Å Hollender, L Rusten, Buskerud Hospital; L Johansen, M Ruppert, Bærum Hospital; A Bailey, A Furuset, V Søyseth, Akershus University Hospital; PF Ekholdt, SØ Gjørstad, Ø Lunde, W Hauge, Fredrikstad Hospital; P Brunsvig, Å Brattland, R Hatlevoll, H Stensheim, Radium Hospital Oslo; A Fjell, B Bergholtz, Aker University Hospital; F Stornes, O reitan, M Wang, K Hornslien, L Breidablikk, Ullevål University Hospital.

References

- Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, Filiberti A, Flechtner H, Fleishman SB, de Haes JC (1993) The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst 85: 365–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alberola V, Camps C, Provencio M, Isla D, Rosell R, Vadell C, Bover I, Ruiz-Casado A, Azagra P, Jimenez U, Gonzales-Larriba JL, Diz P, Cardenal F, Artal A, Carrato A, Morales S, Sanches JJ, de Las PR, Felip E, Lopez-Vivanco G (2003) Cisplatin plus gemcitabine versus a cisplatin-based triplet versus nonplatinum sequential doublets in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a Spanish Lung Cancer Group phase III randomized trial. J Clin Oncol 21: 3207–3213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alberti W (1995) Chemotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis using updated data on individual patients from 52 randomised clinical trials. Non-small Cell Lung Cancer Collaborative Group. BMJ 311: 899–909 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardizzoni A, Tiseo M, Boni L, Rosell R, Fossella FV, Schiller JH, Paesmans M, Radosavljevic A, Paccagnella A, Mazzanti P, Bisset D (2006) CISCA (cisplatin vs carboplatin) meta-analysis: an individual patient data meta-analysis comparing cisplatin versus carboplatin-based chemotherapy in first-line treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). J Clin Oncol 24: 18S [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman B, Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Kaasa S, Sullivan M (1994) The EORTC QLQ-LC13: a modular supplement to the EORTC Core Quality of Life Questionnaire (QLQ-C30) for use in lung cancer clinical trials. EORTC Study Group on Quality of Life. Eur J Cancer 30A: 635–642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunn Jr PA (2002) Chemotherapy for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: who, what, when, why? J Clin Oncol 20: 23S–33S [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvert AH, Newell DR, Gumbrell LA, O'Reilly S, Burnell M, Boxall FE, Siddik ZH, Gore ME, Wiltshaw E (1989) Carboplatin dosage: prospective evaluation of a simple formula based on renal function. J Clin Oncol 7: 1748–1756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardenal F, Lopez-Cabrerizo MP, Anton A, Alberola V, Massuti B, Carrato A, Barneto I, Lomas M, Garcia M, Lianes P, Montalar J, Vadell C, Gonzales-Larriba JL, Nguyen B, Artal A, Rosell R (1999) Randomized phase III study of gemcitabine-cisplatin versus etoposide-cisplatin in the treatment of locally advanced or metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 17: 12–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatelut E, Canal P, Brunner V, Chevreau C, Pujol A, Boneu A, Roche H, Houin G, Bugat R (1995) Prediction of carboplatin clearance from standard morphological and biological patient characteristics. J Natl Cancer Inst 87: 573–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douillard JY, Rosell R, De LM, Carpagnano F, Ramlau R, Gonzales-Larriba JL, Grodzki T, Pereira JR, Le GA, Lorusso V, Clary C, Torres AJ, Dahabreh J, Souquet PJ, Astudillo J, Fournel P, rtal-Cortes A, Jassem J, Koubkova L, His P, Riggi M, Hurteloup P (2006) Adjuvant vinorelbine plus cisplatin versus observation in patients with completely resected stage IB-IIIA non-small-cell lung cancer (Adjuvant Navelbine International Trialist Association [ANITA]): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 7: 719–727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fayers PM, Aaronson NK, Bjordal K, Groenvold M, Curran D, Bottomley A, on behalf of the EORTC Quality of Life Study Group (2001) EORTC QLQ-30 Scoring Manual 3rd edn, ISBN 2-9300 64-22-6

- Fossella F, Pereira JR, von PJ, Pluzanska A, Gorbounova V, Kaukel E, Mattson KV, Ramlau R, Szczesna A, Fidias P, Millward M, Belani CP (2003) Randomized, multinational, phase III study of docetaxel plus platinum combinations versus vinorelbine plus cisplatin for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: the TAX 326 study group. J Clin Oncol 21: 3016–3024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebbia V, Galetta D, Caruso M, Verderame F, Pezzella G, Valdesi M, Borsellino N, Pandolfo G, Durini E, Rinaldi M, Loizzi M, Gebbia N, Valenza R, Tirrito ML, Varvara F, Colucci G (2003) Gemcitabine and cisplatin versus vinorelbine and cisplatin versus ifosfamide+gemcitabine followed by vinorelbine and cisplatin versus vinorelbine and cisplatin followed by ifosfamide and gemcitabine in stage IIIB-IV non small cell lung carcinoma: a prospective randomized phase III trial of the Gruppo Oncologico Italia Meridionale. Lung Cancer 39: 179–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgoulias V, Ardavanis A, Tsiafaki X, Agelidou A, Mixalopoulou P, Anagnostopoulou O, Ziotopoulos P, Toubis M, Syrigos K, Samaras N, Polyzos A, Christou A, Kakolyris S, Kouroussis C, Androulakis N, Samonis G, Chatzidaki D (2005) Vinorelbine plus cisplatin versus docetaxel plus gemcitabine in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a phase III randomized trial. J Clin Oncol 23: 2937–2945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gridelli C, Gallo C, Shepherd FA, Cigolari S, Rossi A, Piantedosi F, Barbera S, Ferrau F, Piazza E, Rosetti F, Clerici M, Bertetto O, Robbiati SF, Frontini L, Sacco C, Castiglione F, Favaretto A, Novello S, Migliorino MR, Gasparini G, Galetta D, Iaffaioli RV, Gebbia V (2003a) Gemcitabine plus vinorelbine compared with cisplatin plus vinorelbine or cisplatin plus gemcitabine for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a phase III trial of the Italian GEMVIN Investigators and the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. J Clin Oncol 21: 3025–3034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gridelli C, Perrone F, Gallo C, Cigolari S, Rossi A, Piantedosi F, Barbera S, Ferrau F, Piazza E, Rosetti F, Clerici M, Bertetto O, Robbiati SF, Frontini L, Sacco C, Castiglione F, Favaretto A, Novello S, Migliorino MR, Gasparini G, Galetta D, Iaffaioli RV, Gebbia V (2003b) Chemotherapy for elderly patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: the Multicenter Italian Lung Cancer in the Elderly Study (MILES) phase III randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 95: 362–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotta K, Matsuo K, Ueoka H, Kiura K, Tabata M, Tanimoto M (2004) Meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials comparing cisplatin to carboplatin in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 22: 3852–3859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Murray T, Xu J, Smigal C, Thun MJ (2006) Cancer statistics, 2006. CA Cancer J Clin 56: 106–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly K, Crowley J, Bunn Jr PA, Presant CA, Grevstad PK, Moinpour CM, Ramsey SD, Wozniak AJ, Weiss GR, Moore DF, Israel VK, Livingston RB, Gandara DR (2001) Randomized phase III trial of paclitaxel plus carboplatin versus vinorelbine plus cisplatin in the treatment of patients with advanced non – small-cell lung cancer: a Southwest Oncology Group trial. J Clin Oncol 19: 3210–3218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kortsik C, Albrecht P, Elmer A (2003) Gemcitabine and carboplatin in patients with locally advanced or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: a prospective phase II study. Lung Cancer 40: 85–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Chevalier T, Brisgand D, Douillard JY, Pujol JL, Alberola V, Monnier A, Riviere A, Lianes P, Chomy P, Cigolari S (1994) Randomized study of vinorelbine and cisplatin versus vindesine and cisplatin versus vinorelbine alone in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: results of a European multicenter trial including 612 patients. J Clin Oncol 12: 360–367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Chevalier T, Scagliotti G, Natale R, Danson S, Rosell R, Stahel R, Thomas P, Rudd RM, Vansteenkiste J, Thatcher N (2005) Efficacy of gemcitabine plus platinum chemotherapy compared with other platinum containing regimens in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis of survival outcomes. Lung Cancer 47: 69–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martoni A, Marino A, Sperandi F, Giaquinta S, Di FF, Melotti B, Guaraldi M, Palomba G, Preti P, Petralia A, Artioli F, Picece V, Farris A, Mantovani L (2005) Multicentre randomised phase III study comparing the same dose and schedule of cisplatin plus the same schedule of vinorelbine or gemcitabine in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Eur J Cancer 41: 81–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mountain CF (1997) Revisions in the international system for staging lung cancer. Chest 111: 1710–1717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osoba D, Rodrigues G, Myles J, Zee B, Pater J (1998) Interpreting the significance of changes in health-related quality-of-life scores. J Clin Oncol 16: 139–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfister DG, Johnson DH, Azzoli CG, Sause W, Smith TJ, Baker Jr S, Olak J, Stover D, Strawn JR, Turrisi AT, Somerfield MR (2004) American Society of Clinical Oncology treatment of unresectable non-small-cell lung cancer guideline: update 2003. J Clin Oncol 22: 330–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plessen C, Bergman B, Andresen O, Bremnes RM, Sundstrom S, Gilleryd M, Stephens R, Vilsvik J, Aasebo U, Sorenson S (2006) Palliative chemotherapy beyond three courses conveys no survival or consistent quality-of-life benefits in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer 95: 966–973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ries LAG, Harkins D, Krapcho M, Mariotto A, Miller BA, Feuer EJ, Clegg L, Eisner MP, Horner MJ, Howlader N, Hayat M, Hankey BF, Edwards BK (2006) SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2003. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/,1975_2003/. Based on November 2005 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- Rudd RM, Gower NH, Spiro SG, Eisen TG, Harper PG, Littler JA, Hatton M, Johnson PW, Martin WM, Rankin EM, James LE, Gregory WM, Qian W, Lee SM (2005) Gemcitabine plus carboplatin versus mitomycin, ifosfamide, and cisplatin in patients with stage IIIB or IV non-small-cell lung cancer: a phase III randomized study of the London Lung Cancer Group. J Clin Oncol 23: 142–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandler AB, Nemunaitis J, Denham C, von PJ, Cormier Y, Gatzemeier U, Mattson K, Manegold C, Palmer MC, Gregor A, Nguyen B, Niyikiza C, Einhorn LH (2000) Phase III trial of gemcitabine plus cisplatin versus cisplatin alone in patients with locally advanced or metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 18: 122–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scagliotti GV, De MF, Rinaldi M, Crino L, Gridelli C, Ricci S, Matano E, Boni C, Marangolo M, Failla G, Altavilla G, Adamo V, Ceribelli A, Clerici M, Di CF, Frontini L, Tonato M (2002) Phase III randomized trial comparing three platinum-based doublets in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 20: 4285–4291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiller JH, Harrington D, Belani CP, Langer C, Sandler A, Krook J, Zhu J, Johnson DH (2002) Comparison of four chemotherapy regimens for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 346: 92–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sederholm C, Hillerdal G, Lamberg K, Kolbeck K, Dufmats M, Westberg R, Gawande SR (2005) Phase III trial of gemcitabine plus carboplatin versus single-agent gemcitabine in the treatment of locally advanced or metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: the Swedish Lung Cancer Study Group. J Clin Oncol 23: 8380–8388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smit EF, van Meerbeeck JP, Lianes P, Debruyne C, Legrand C, Schramel F, Smit H, Gaafar R, Biesma B, Manegold C, Neymark N, Giaccone G (2003) Three-arm randomized study of two cisplatin-based regimens and paclitaxel plus gemcitabine in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a phase III trial of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Lung Cancer Group – EORTC 08975. J Clin Oncol 21: 3909–3917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith IE, O'Brien ME, Talbot DC, Nicolson MC, Mansi JL, Hickish TF, Norton A, Ashley S (2001) Duration of chemotherapy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a randomized trial of three versus six courses of mitomycin, vinblastine, and cisplatin. J Clin Oncol 19: 1336–1343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Socinski MA, Schell MJ, Peterman A, Bakri K, Yates S, Gitten R, Unger P, Lee J, Lee JH, Tynan M, Moore M, Kies MS (2002) Phase III trial comparing a defined duration of therapy versus continuous therapy followed by second-line therapy in advanced-stage IIIB/IV non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 20: 1335–1343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley KE (1980) Prognostic factors for survival in patients with inoperable lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 65: 25–32 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan EH, Szczesna A, Krzakowski M, Macha HN, Gatzemeier U, Mattson K, Wernli M, Reiterer P, Hui R, Pawel JV, Bertetto O, Pouget JC, Burillon JP, Parlier Y, Abratt R (2005) Randomized study of vinorelbine – gemcitabine versus vinorelbine – carboplatin in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 49: 233–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO (1979) WHO Handbook for Reporting the Results of Cancer Treatment. Geneva: World Health Organization [Google Scholar]

- Wozniak AJ, Crowley JJ, Balcerzak SP, Weiss GR, Spiridonidis CH, Baker LH, Albain KS, Kelly K, Taylor SA, Gandara DR, Livingston RB (1998) Randomized trial comparing cisplatin with cisplatin plus vinorelbine in the treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a Southwest Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol 16: 2459–2465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zatloukal P, Petruzelka L, Zemanova M, Kolek V, Skrickova J, Pesek M, Fojtu H, Grygarkova I, Sixtova D, Roubec J, Horenkova E, Havel L, Prusa P, Novakova L, Skacel T, Kuta M (2003) Gemcitabine plus cisplatin vs gemcitabine plus carboplatin in stage IIIb and IV non-small cell lung cancer: a phase III randomized trial. Lung Cancer 41: 321–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]