Abstract

The ATP-sensitive K+-channel (KATP channel) plays a key role in insulin secretion from pancreatic β cells. It is closed both by glucose metabolism and the sulfonylurea drugs that are used in the treatment of noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, thereby initiating a membrane depolarization that activates voltage-dependent Ca2+ entry and insulin release. The β cell KATP channel is a complex of two proteins: Kir6.2 and SUR1. The former is an ATP-sensitive K+-selective pore, whereas SUR1 is a channel regulator that endows Kir6.2 with sensitivity to sulfonylureas. A number of drugs containing an imidazoline moiety, such as phentolamine, also act as potent stimulators of insulin secretion, but their mechanism of action is unknown. We have used a truncated form of Kir6.2, which expresses independently of SUR1, to show that phentolamine does not inhibit KATP channels by interacting with SUR1. Instead, our results argue that phentolamine may interact directly with Kir6.2 to produce a voltage-independent reduction in channel activity. The single-channel conductance is unaffected. Although the ATP molecule also contains an imidazoline group, the site at which phentolamine blocks is not identical to the ATP-inhibitory site, because phentolamine block of an ATP-insensitive mutant (K185Q) is normal. KATP channels also are found in the heart where they are involved in the response to cardiac ischemia: they also are blocked by phentolamine. Our results suggest that this may be because Kir6.2, which is expressed in the heart, forms the pore of the cardiac KATP channel.

It has been known for many years that certain drugs that contain an imidazoline nucleus, including several classical α-adrenoreceptor antagonists, act as potent stimulators of insulin secretion (1–4). Good evidence exists that the insulinotropic effects of these drugs do not result from antagonism of α-adrenoreceptors, but rather from inhibition of ATP-sensitive K+-channels (KATP channels) in the β cell plasma membrane (2–6). The activity of KATP channels sets the β cell resting potential and their inhibition by imidazolines leads to membrane depolarization, activation of Ca2+-dependent electrical activity, and a rise in [Ca2+]i that triggers insulin release (7). One of the most potent of the imidazolines is phentolamine, which blocks native KATP currents in β cells half-maximally at 0.7 μM when added to the intracellular solution (6).

In addition to their effects on insulin secretion, imidazolines have cardiovascular actions that are independent of α-adrenoreceptors. For example, phentolamine causes peripheral vasodilation, increases heart rate, and enhances myocardial contractility (8). It also increases the duration of the ventricular action potential, an effect that probably results from the ability of the drug to block cardiac KATP channels (9). The potency of inhibition (Ki = 1 μM) is similar to that found for β cell KATP currents (9).

The mechanism by which imidazolines inhibit KATP currents is unknown. The pharmacology of imidazoline block of KATP channels does not match that of either of the major subtypes of imidazoline receptor (I1 or I2), which has led to the suggestion that the channel is associated with a novel receptor for imidazolines (10). It has been speculated that this receptor might form part of the KATP channel itself (6).

The KATP channel is a complex of two proteins: a pore-forming subunit, Kir6.2, and the sulfonylurea receptor, SUR1 (11, 12). The former acts as an ATP-sensitive K-channel pore whereas SUR1 is a channel regulator that endows Kir6.2 with sensitivity to drugs such as the inhibitory sulfonylureas and the K-channel opener diazoxide (13). We have explored whether phentolamine interacts with SUR1 or with Kir6.2, by studying the effect of phentolamine on the Kir subunit in the absence of the sulfonylurea receptor. Kir6.2 does not express functional K-ATP currents alone (11, 12). We therefore have examined the effect of phentolamine on a C-terminally truncated form of Kir6.2 in which the last 26 (Kir6.2ΔC26) or 36 (Kir6.2ΔC36) C-terminal amino acids have been deleted. This channel is able to express significant current in the absence of SUR1 (13).

METHODS

Molecular Biology.

A 26 (or 36) amino acid C-terminal deletion of mouse Kir6.2 (GenBank D50581) was made by introduction of a stop codon at the appropriate residue using site-directed mutagenesis. Site-directed mutagenesis was carried out by subcloning the appropriate fragments into the pALTER vector (Promega). Kir6.2, rat Kir1.1a (GenBank X722341, ref. 14), and rat SUR1 (GenBank L40624, ref. 15) cRNAs were synthesized as previously described (16).

Electrophysiology.

Xenopus oocytes were defolliculated and injected with ≈0.04 ng cRNA encoding wild-type (wt) Kir6.2 plus 2 ng SUR1 cRNA, or with ≈2 ng Kir6.2ΔC26 cRNA, ≈2ng Kir6.2ΔC36 cRNA or ≈0.04 ng Kir1.1a cRNA. The final injection volume was ≈50 nl per oocyte. Isolated oocytes were maintained in modified Barth’s solution (16) supplemented with 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 5 mM pyruvate. Currents were studied 1–4 days after injection. Macroscopic currents were recorded from giant inside-out patches (16–17) using an EPC7 patch-clamp amplifier (List Electronics, Darmstadt, Germany) at 20–24°C using 200–400 kΩ electrodes. The holding potential was 0 mV, and currents were evoked by repetitive 3-s voltage ramps from −110 mV to +100 mV. The mean current amplitude at −100 mV, measured in nucleotide-free solution immediately after patch excision, varied between 0.5 and 5 nA for wtKir6.2 coexpressed with SUR1, and was between 0.2 and 1 nA for Kir6.2ΔC26 currents. Current and voltage signals were filtered at 5 kHz and stored on digital audio tape. Currents subsequently were digitized at 5 kHz (filter, 2 kHz) using a Digidata 1200 Interface and pClamp 6.0 software (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA), for analysis. Single-channel currents were recorded from inside-out patches at −60 mV and digitized at 10 kHz (filter, 5 kHz).

The pipette (external) solution contained 140 mM KCl, 1.2 mM MgCl2, 2.6 mM CaCl2, and 5 mM Hepes (pH 7.4). The intracellular (bath) solution contained 107 mM KCl, 10 mM EGTA, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2, and 10 mM Hepes (pH 7.2 with KOH; final K+ ≈140 mM). Exchange of solutions was achieved by positioning the patch electrode in the mouth of one of a series of adjacent inflow pipes containing the test solutions.

HEK293 cells were cultured and transiently transfected with the pcDNA3 vector (Invitrogen) containing the coding sequence of Kir6.2ΔC36 using Lipofectamine (GIBCO/BRL) (12, 13). We used Kir6.2ΔC36, rather than Kir6.2ΔC26, as it expresses larger currents. Whole-cell currents were studied 48–72 hr after transfection. The pipette solution contained 107 mM KCl, 1.2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2, 10 mM EGTA, 5 mM Hepes (pH 7.2 with KOH; total K ≈140 mM) and 0.3 mM ATP. The bath solution contained 5.6 mM KCl, 140 mM NaCl, 2.6 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM MgCl2, and 5 mM Hepes (pH 7.4). Currents were evoked by ± 20 mV 200-ms depolarizations from a holding potential of −70 mV.

Data Analysis.

All data is given as mean ± one SEM. The symbols in the figures indicate the mean, and the vertical bars indicate 1 SEM. The slope conductance (G) was measured by fitting a straight line to the data between −20 mV and −100 mV: the average of 3–5 consecutive ramps was calculated in each solution. KATP currents commonly decline in amplitude after patch excison, at a variable rate (7, 13). To control for this rundown, test solutions were alternated with control solutions, and G was expressed as a fraction of the slope conductance in control solution (Gc). For Kir6.2/SUR1 currents, phentolamine dose-response relationships were fit to the Hill equation: 100 G/Gc = B + (100 − B)/(1 + ([phentolamine]/Ki)h)), where [phentolamine] is the phentolamine concentration, Ki is the drug concentration at which inhibition is half maximal, h is the slope factor (Hill coefficient), and B is the background current that is not blocked by 100 μM phentolamine. Kir6.2ΔC26 currents were smaller than Kir6.2/SUR2 currents (13). Consequently, the background current contributes a greater fraction of the total current and, because of rundown, this fraction increases throughout the course of the experiment (i.e., B is not constant). Therefore the background current was subtracted from Kir6.2ΔC26 currents and B was set to zero. The background current for Kir6.2ΔC26 currents amounted to 145 ± 35 pS (n = 6) and for wild-type currents was 175 ± 45 pS (n = 6).

Statistical significance was tested using Student’s t test. Single-channel currents were analyzed using a combination of pClamp and in-house software. Single-channel current amplitudes were calculated from an all-points amplitude histogram. For measurements of open and closed times, events were detected using a 50% threshold level method, and a burst was defined as two openings separated by an interval of <0.6 ms (twice the mean short closed time).

RESULTS

We first recorded wtKATP currents from giant inside-out patches excised from Xenopus oocytes coinjected with wtKir6.2 and SUR1. As previously described (15), the patch conductance was low in the cell-attached configuration but increased spontaneously upon excision of the patch into a nucleotide-free solution. These currents were blocked by 1 mM ATP (15), demonstrating that oocytes coinjected with wtKir6.2 and SUR1 express ATP-sensitive K-currents. Similar results were obtained for Kir6.2ΔC26 and Kir6.2ΔC36 currents, confirming that Kir6.2 has an intrinsic ATP-inhibitory site (13).

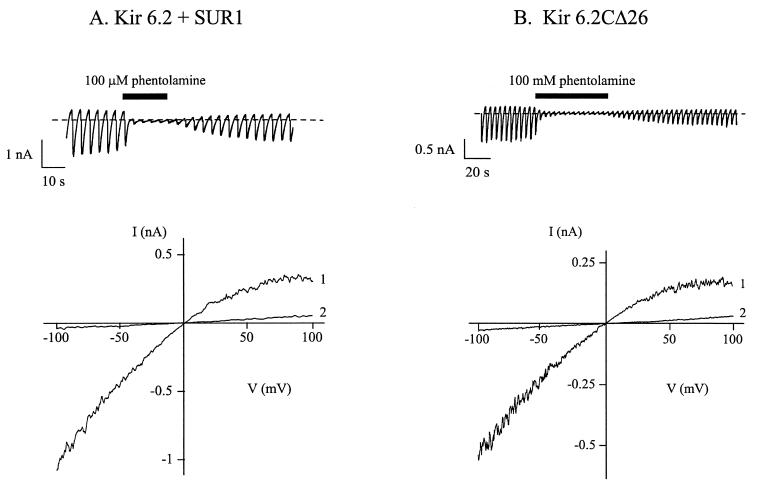

Application of 100 μM phentolamine to the intracellular solution reversibly inhibited wtKATP currents by 97.1 ± 0.7% (n = 7) (Fig. 1A). A similar degree of inhibition (91 ± 3.9%, n = 6) was observed for Kir6.2ΔC26 currents (Fig. 1B) and for Kir6.2ΔC36 currents (data not shown). In both cases the block by phentolamine was voltage-independent.

Figure 1.

Effects of imidazolines on wtK-ATP currents and Kir6.2ΔC26 currents. (A and B) Macroscopic currents (Upper) and associated current-voltage relations (Lower) recorded from two different inside-out patches in response to a series of voltage ramps from −110 to +100 mV. Oocytes were coinjected with cRNAs encoding wtKir6.2 and SUR1 (A), or Kir6.2ΔC26 (B). The holding potential was 0 mV. (Upper) The dotted line indicates the zero current level. Phentolamine (100 μM) was added to the intracellular (bath) solution as indicated by the solid line. (Lower) 1, control; 2, 100 μM phentolamine.

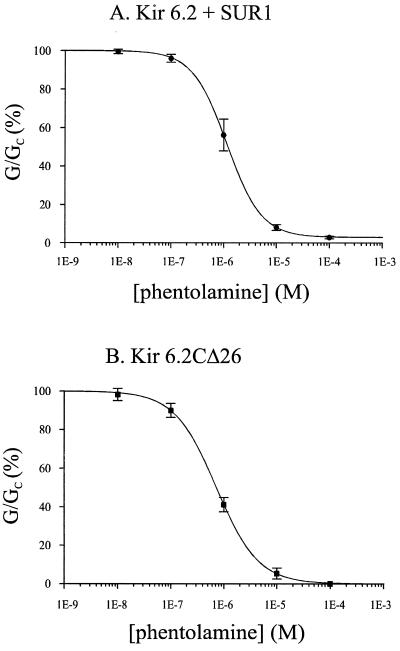

The relationship between phentolamine concentration and the amplitude of the wtKATP current is given in Fig. 2A. It is clear that the dose-response curve can be well fit by a single-site model, with a mean Ki of 1.13 ± 0.38 μM and a Hill coefficient of 1.28 ± 0.11 (n = 6). A similar relationship was found for KirΔC26 currents (Fig. 2B), and the mean Ki (0.77 ± 0.16 μM, n = 6) and Hill coefficient (1.14 ± 0.38) were not significantly different from those of wtKATP currents. These data suggest that the Kir6.2 subunit may possess an intrinsic phentolamine inhibitory site. The fact that the Hill coefficient was close to unity also suggests that only a single phentolamine molecule needs to interact with the channel to cause inhibition. It is believed that four Kir6.2 subunits come together to form the pore (18, 19), but we do not know whether each Kir6.2 subunit possesses its own phentolamine binding site, or whether there is a single site with residues contributed by all four subunits. The data also indicate that coexpression with SUR1 does not enhance the phentolamine sensitivity of Kir6.2, in contrast to what is observed for the inhibitory effects of ATP (13).

Figure 2.

Concentration-dependence of phentolamine block of wtK-ATP currents and Kir6.2ΔC26 currents. Mean dose-response relationships for phentolamine block of wtKir6.2/SUR1 currents (A, n = 6) or Kir6.2ΔC26 currents (B, n = 6). Test solutions were alternated with control solutions and the slope conductance (G) is expressed as a percentage of the mean (Gc) of that obtained in control solution before and after exposure to the drug. The lines are the best fit of the mean data to the Hill equation (see Methods). For wtKir6.2/SUR1 currents, Ki = 1.15 μM, h = 1.33, and B = 2.93. For Kir6.2ΔC26 currents, Ki = 0.72 μM, h = 1.1: the current in the presence of 100 μM phentolamine was taken as the background current and was subtracted (this corresponded to <10% of the total current).

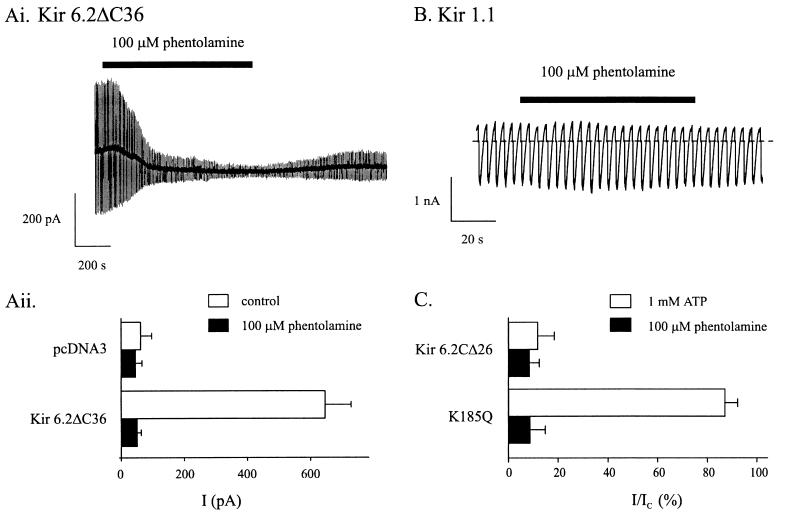

To exclude the possibility that truncated Kir6.2 couples to an endogenous protein in the Xenopus oocyte that endows phentolamine sensitivity, we also examined the effects of the drug on Kir6.2ΔC36 currents expressed in the mammalian cell line HEK293. Whole-cell currents recorded from HEK293 cells transfected with Kir6.2ΔC36 increased with time after establishment of the whole-cell configuration when dialyzed intracellularly with 0.3 mM ATP. This increase in current reflects the washout of endogenous ATP (7, 13). Washout-currents were blocked by 92.2 ± 1.8% by 100 μM extracellular phentolamine (Fig. 3A), a value similar to that found when Kir6.2CΔ26 was expressed in oocytes. The slower time course of the block when phentolamine is applied to the extracellular rather than intracellular membrane surface is observed for native β cells also (unpublished observations). This presumably reflects the access of phentolamine to its binding site and suggests it may lie on the inner side of the membrane.

Figure 3.

(A) Phentolamine block of K-ATP currents expressed in HEK293 cells. (Ai) Whole-cell currents recorded from an HEK293 cell transfected with cDNA encoding Kir6.2ΔC36 in response to alternate ± 20 mV pulses from a holding potential of −70 mV. (Aii) Mean whole-cell current amplitudes recorded from HEK293 cells transfected with cDNA encoding Kir6.2Δ36 or pcDNA3 alone, in control solution and after the addition of 100 μM phentolamine. Cells were dialyzed with 0.3 mM ATP. (B and C) Selectivity of phentolamine block. (B) Macroscopic currents recorded in response to a series of voltage ramps from −110 to +100 mV from an inside-out patch excised from an oocyte injected with Kir1.1a cRNA. The holding potential was 0 mV. The dotted line indicates the zero current level. Phentolamine (100 μM) was added to the intracellular (bath) solution as indicated by the solid line. (C) Percentage inhibition of macroscopic currents by intracellular ATP (empty bars) or phentolamine (filled bars). Currents are expressed as a fraction of their amplitude before addition of the inhibitor. Inside-out patches were excised from oocytes injected with cRNA encoding wtKir6.2ΔC26 (n = 6) or wtKir6.2ΔC26-K185Q (n = 6).

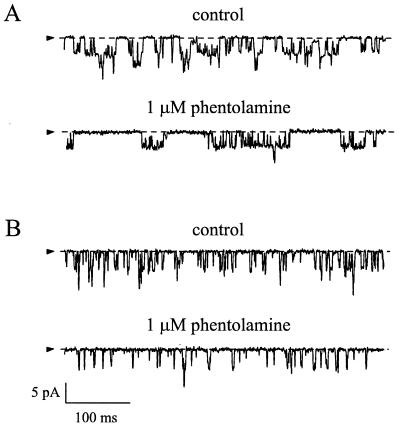

We next examined the effect of phentolamine on wtKATP currents and Kir6.2ΔC26 currents at the single-channel level (Fig. 4). As previously reported (13), no difference in the unitary conductance of wtKATP and Kir6.2ΔC26 channels was found (Table 1). However, the kinetics of Kir6.2ΔC26 currents were faster (Table 1). For wtKATP currents, the open time distribution was fit by a single exponential, with a mean time constant of 1.49 ms. The closed time distribution was best fit by the sum of two exponentials, with mean time constants of 0.32 ms and 6.2 ms, respectively. These values are similar to those previously reported for native and wtKATP channels (7, 12). As seen in Fig. 4A, KATP channel openings occurred in bursts, which were separated by longer closed intervals. The short closed time is primarily determined by openings within a burst and the long closed time reflects the inter-burst intervals. The mean short closed time of Kir6.2ΔC26 currents was not significantly different from that of wtKATP channels; however, the mean burst duration and the mean open time were significantly shorter (Table 1). This produces a decrease in the channel open probability, which may, in part, explain why we observed smaller amplitude macroscopic currents when Kir6.2ΔC26 was expressed alone than when it was coexpressed with SUR1 (13).

Figure 4.

Effects of phentolamine on single-channel currents. Single-channel currents recorded at −60 mV in the presence or absence of 1 μM intracellular phentolamine from an inside-out patch excised from an oocyte coinjected with Kir6.2 and SUR1 cRNAs (A) or with Kir6.2ΔC26 cRNA (B). The arrow indicates the zero current level.

Phentolamine did not alter the amplitude of either wtKATP or Kir6.2ΔC26 single-channel currents, indicating that it does not act as an open channel blocker (Table 1; Fig. 4). However, it markedly decreased the channel activity. For both wtKATP currents and Kir6.2ΔC26 currents this effect resulted primarily from a reduction in the mean long closed time.

We next examined whether the site at which phentolamine mediates KATP channel inhibition was identical with that involved in ATP block, by examining the effect of phentolamine on a mutant form of Kir6.2 (Kir6.2ΔC26-K185Q), which has much lower ATP sensitivity. In this mutant, the Ki for ATP block is reduced from 106 μM to 4.2 mM (13). However, 100 μM phentolamine blocked Kir6.2ΔC26-K185Q currents as effectively as Kir6.2ΔC26 currents (Fig. 3C). This argues that the phentolamine-inhibitory site is not identical with that for ATP, although it remains possible that both sites may share certain residues.

Finally, we explored whether phentolamine is able to inhibit Kir1.1a, a related Kir channel that shares ≈45% sequence identity with Kir6.2. As shown in Fig. 3B, 100 μM phentolamine was without significant effect on Kir1.1a. The mean conductance in the presence of the drug was 99.0 ± 2.7% (n = 6) of that in control solution.

DISCUSSION

Our results demonstrate that the imidazoline phentolamine does not inhibit the β cell wtKATP channel by binding to the sulfonylurea receptor SUR1. This explains why imidazolines do not displace [3H]glibenclamide binding to β cell membranes (20). It also is consistent with the finding that the sensitivity of the native β cell KATP channel to imidazolines, unlike that to sulfonylureas (21), does not decline after patch excision or after mild proteolysis of the intracellular membrane (5).

The fact that phentolamine blocks Kir6.2ΔC26 currents as potently as Kir6.2/SUR1 currents suggests that the binding site for phentolamine resides on Kir6.2, or on a separate protein, endogenously expressed in Xenopus oocytes, which regulates Kir6.2 activity. Although we cannot completely exclude the latter possibility, we favor the idea that Kir6.2 is itself sensitive to phentolamine. This is because the extent of block of Kir6.2ΔC26 currents did not depend on the current size, as might be expected if an endogenous oocyte protein were to mediate the inhibitory effect of the drug. The observation that Kir6.2ΔC36 currents also were blocked by phentolamine in HEK293 cells also makes it less likely that phentolamine sensitivity is conferred by an endogenous subunit as this protein also would have to be expressed in HEK293 cells. Because both the native β cell (6) and cardiac KATP channel (9) are blocked by phentolamine with a potency similar to the one we report for Kir6.2ΔC26 currents, any imidazoline receptor distinct from Kir6.2 itself also would have to be expressed in these cells. Finally, a brief report that Kir6.2 can be radiolabeled by cibenzoline, another imidazoline that blocks KATP channels and stimulates insulin secretion (22), has appeared (23). These data argue that phentolamine interacts directly with Kir6.2 to close the pore.

Although both ATP and phentolamine block Kir6.2, the site at which they do so does not appear to be composed of identical amino acids, because mutation of K185Q markedly decreases the ATP sensitivity (13) yet was without significant effect on phentolamine block. It remains possible, however, that the binding sites for ATP and phentolamine may share some of the same residues. The fact that the adenosine molecule includes an imidazoline moiety favors this possibility.

Kir6.2 is expressed in β cells, heart, brain, and skeletal muscle and therefore may serve as the pore-forming subunit of the KATP channel in all of these tissues (12). By contrast, the sulfonylurea receptor, which acts as the regulatory subunit of the KATP channel, is different in cardiac muscle, being SUR2A rather than SUR1 (24). Our demonstration that Kir6.2 serves as the target for imidazolines therefore explains why native cardiac and β cell KATP channels share a similar sensitivity to phentolamine. Imidazolines are being explored as novel oral hypoglycemic agents for the treatment of noninsulin-dependent diabetes. Our results indicate that this strategy requires careful consideration because these drugs are likely to have side effects in other tissues where Kir6.2 is expressed, such as heart, brain, and skeletal muscle. Finally, we point out that in addition to the sulfonylureas and the imidazolines, a range of other drugs inhibit KATP channels: these include barbiturates, antimalarial agents such as quinine, and certain plant extracts (25). It will be important to consider whether these drugs mediate their effects by interaction with Kir6.2 rather than SUR1, as this has obvious implications for their tissue specificity.

Table 1.

Properties of wtKATP and Kir6.2ΔC26 single-channel currents

| Mean open time, ms | Mean short closed time, ms | Mean long closed time, ms | Mean burst duration, ms | Mean openings per burst | i (pA, at −60 mV) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| wtKATP currents | ||||||

| Control (n = 3) | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 0.32 ± 0.02 | 6.2 ± 0.7 | 4.3 ± 0.8 | 3.3 ± 0.3 | 4.4 ± 0.2 |

| Phentolamine (n = 3) | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 0.34 ± 0.02 | 17.5 ± 6.1 | 4.7 ± 1.0 | 3.3 ± 0.3 | 4.3 ± 0.2 |

| Kir6.2ΔC26 currents | ||||||

| Control (n = 3) | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.29 ± 0.03 | 3.8 ± 1.5 | 2.1 ± 0.4 | 2.5 ± 0.2 | 4.3 ± 0.2 |

| Phentolamine (n = 3) | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 0.31 ± 0.01 | 11.4 ± 3.3 | 2.0 ± 0.4 | 2.5 ± 0.1 | 4.3 ± 0.3 |

i, single-channel current amplitude (at −60mV).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. S. Tucker for making the cRNAs, Dr. C. Zhao for transfection of HEK293 cells, and Dr. P. Smith for writing the analysis programs. We also thank Dr. G. Bell (University of Chicago) for the gift of rat SUR1 and Steve Hebert for the gift of Kir1.1a. The work was supported by the Wellcome Trust and the British Diabetic Association.

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the Proceedings Office.

Abbreviations: KATP channel, ATP-sensitive potassium channel; wt, wild type.

References

- 1.Chan S L F. Clin Sci. 1993;85:671–677. doi: 10.1042/cs0850671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Plant T D, Henquin J C. Br J Pharmacol. 1990;101:115–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1990.tb12099.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jonas J C, Plant T D, Henquin J C. Br J Pharmacol. 1991;107:1847–1850. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan S L F, Dunne M J, Stillings M R, Morgan N G. Eur J Pharmacol. 1991;204:41–48. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(91)90833-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dunne M J, Harding E A, Jaggar J H, Squires P E, Liang R, Kane C, James R F L, London N J M. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1995;763:242–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1995.tb32410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dunne M J. Br J Pharmacol. 1991;103:1847–1850. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1991.tb12340.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ashcroft F M, Rorsman P. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 1989;54:87–143. doi: 10.1016/0079-6107(89)90013-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gould L, Reddy C V R. Am Heart J. 1976;92:397–402. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(76)80121-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee K, Groh W J, Blair A, Maylie J G, Adelman J P. Eur J Pharmacol. 1995;285:309–312. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00525-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olmos G, Kulkarni R N, Haque M, MacDermot J. Eur J Pharmacol. 1994;262:41–48. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(94)90026-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Inagaki N, Gonoi T, Clement J P, Iv, Namba N, Inazawa J, Gonzalez G, Aguilar-Bryan L, Seino S, Bryan J. Science. 1995;270:1166–1169. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5239.1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sakura H, Ämmälä C, Smith P A, Gribble F M, Ashcroft F M. FEBS Lett. 1995;377:338–344. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01369-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tucker S J, Gribble F M, Zhao C, Trapp S, Ashcroft F M. Nature (London) 1997;387:179–183. doi: 10.1038/387179a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ho K, Nichols C G, Lederer W J, Lytton J, Vassilev P M, Kanazirska M V, Hebert S C. Nature (London) 1993;362:31–38. doi: 10.1038/362031a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aguilar-Bryan L, Nichols C G, Wechsler S W, Clement J P, Boyd A E, González G, Herrera-Sosa H, Nguy K, Bryan J, Nelson D A. Science. 1995;268:423–425. doi: 10.1126/science.7716547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gribble F M, Ashfield R, Ämmälä C, Ashcroft F M. J Physiol. 1997;498:87–98. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp021843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hilgemann D W, Nicoll D A, Phillipson K D. Nature (London) 1991;352:715–718. doi: 10.1038/352715a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clement J P, IV, Kunjilwar K, Gonzalez G, Schwanstecher M, Panten U, Aguilar-Bryan L, Bryan J. Neuron. 1997;18:727–838. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80321-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Inagaki N, Gonoi T, Seino S. FEBS Lett. 1997;409:232–236. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00488-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brown C A, Chan S L F, Stillings M R, Smith S A, Morgan N G. Br J Pharmacol. 1993;110:1017–1022. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13915.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Proks P, Ashcroft F M. Pflügers Arch. 1993;424:63–72. doi: 10.1007/BF00375103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ischida-Takahashi A, Horie M, Tsuura Y, Ischida H, Ai T, Sasayama S. Br J Pharmacol. 1996;117:1749–1755. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15349.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mukai, E., Ischida, H., Kato, S., Tsuura, Y., Yasuda, N., Inagaki, N., Seino, Y. & Seino, S. (1997) J. Jpn. Diab. Soc. 40, Suppl. 1, 213.

- 24.Inagaki N, Gonoi T, Clement J P, IV, Wang C Z, Aguilar-Bryan L, Bryan J, Seino S. Neuron. 1996;16:1011–1017. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80124-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ashcroft F M, Ashcroft S J H. Cell Signalling. 1990;2:197–214. doi: 10.1016/0898-6568(90)90048-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]